-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2018; 7(5): 178-184

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20180705.02

Establishing the Critical Barriers to Academia-Industry Collaboration in Building Construction Research in Ghana

Dok Yen D. M.1, Adinyira E.2, Dauda A. M.1

1Department of Building Technology, Tamale Technical University, Tamale, Ghana

2Department of Building Technology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

Correspondence to: Dok Yen D. M., Department of Building Technology, Tamale Technical University, Tamale, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In general terms, very little formal research collaboration is seen between the construction in the academia and the construction industry in Ghana. The aim of this research was to establish the critical barriers to academia-industry in the Ghanaian building construction industry. The respondents for this study were consist of a total of 116 construction professionals, consisting of Ghana Institute of Construction (GIOC) corporate members from the industry, and academics from tertiary academic institutions that run postgraduate construction programmes in Ghana as at 2016. Data was analysed using the relative important index (RII). The Barriers were identified as; difficulty in ensuring equal voice in decision–making, potential conflicts among collaborating individuals/institutions, the problem of Power dynamics or control among members, difficulties in identifying partners with a common research agenda, and lack of trust among partners. This research finding would provide an opportunity for academia-industry to come out with effective solution to overcome the barriers to collaborative issues within the academia-industry in construction research. The researchers recommend that academia and industry should have regular dialogue and appraisal to come out with a collaborative framework to address critical barriers to academia-industry collaborative research in the Ghanaian construction.

Keywords: Barriers, Academia-Industry, Collaboration, Building, Construction, Research, Ghana

Cite this paper: Dok Yen D. M., Adinyira E., Dauda A. M., Establishing the Critical Barriers to Academia-Industry Collaboration in Building Construction Research in Ghana, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 7 No. 5, 2018, pp. 178-184. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20180705.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Notwithstanding the fact that, several construction research works have been done by the academics in the tertiary institutions in the Ghana. It is sad to know that, a large number of these research works have not moved from the pure stage to the applied stage. This is partly due to the reason been that, there is no formal research collaboration between the academia and industry. Moreover, considering the complexities normally associated with dealing with partners from different sectors such as the academia and industry sometimes with diverse interest (Gustavsson and Gohary, 2014). For instance where; the academia is aiming to make full exposure and publication of research outcome to support academic teaching and learning activities, while the industry, limits disclosure due to its profit because such findings may be good marketable and profit making product. CDD-Ghana, (2005). In view of the above and the numerous challenges surrounding the Ghanaian.Construction industry inspired these researchers to undertake this study to establish the critical barriers to academia- industry collaborative research in the Ghanaian construction industry, which would go a long way to lay a solid foundation that, can overcome the academia-industry collaboration challenges in the Ghanaian construction industry.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Barriers to Collaborative Research

- The forces against collaboration are strong and elusive. First, there is a philosophy of bias against it. We are educated at schools that leaning over to look at your neighbour’s work, especially in exams is cheating and that what is important is the ability for one to be able to do things on your own. The nature of examination structure is mostly centred extremely on the principle of individual principle accountability (Chesterman, 1998). Thereby making the conception of collaboration weakly represented. The standards of life are often defined by our modern society base on the capability of what an individual /person possesses, such as independent possessions, thought or action. Funny enough, we easily turn to forget that the whole assessment of the individual in itself is socially conceived (Gergen, 1991). Nevertheless, assessing the return on collaborative research is challenging for several reasons such as: identifying the research problem, the methodology to agree upon, the non-uniformity of research designs among partners, the degree of collaborators participation range depending on the duration of the project whether short period or long-term (Jagosh et al., 2012).Collaborating partner's inability to make inputs into partnership desires, aims and objectives as anticipated, as well as the lack of trust among partners is a big challenge to collaborative research (Akintoye and Main, 2007). According to Chun-Yu et al., (2013), difficulties can arise in collaborative research as a result of the planning and format or style of presentation of the research; also the discovery was that the differences in approach to things and issues can have a positive or negative effect on collaboration. Furthermore, the complexity of dealing with practitioners, stakeholders, with different backgrounds is a great barrier to deal with (Gustavsson and Gohary, 2014). Such as the barrier to change construction project practices; from having inflexible and impervious borders between stakeholders, professionals, and processes, to further collaborative advancement (Bresnen and Marshall, 2000; Eriksson, 2010, 2011; Kadefors, 2004; Nystrom, 2005). On the other hand, Adinyira et al., (2011), identified the barriers of collaborative research in their study as; competition; lack of information and operational differences. Likewise, Dok Yen (2010), study shows that equal voices in decision–making and potential conflicts of collaborating individuals/ institutions were impediments to collaborative research. Barriers to collaboration can come as a result of differences in individual aims/objectives, priorities, expectations, or conflicts during partnerships; differences in the approach to work or communication, the leaning of some individuals, institution or organisations to depend on others to manage their part of the work or contribution and power dynamics among members (Arvaja et al., 2007). The difficulty of collaborative research sometimes has to do with how to battle with partners working together as equals, considering the fact that, though they seem to have a common goal, at the same time each collaborator still has his own, possible target wanting to accomplish, hence making the partners to have indirectly different goals and not too many common objectives; because the those seen to be common objectives are just based on the founders of the partnership and may not really be the real interest of all partners, this often causes each partner to take legitimate advantage of the collaborative project to achieve individual benefits and objectives rather than collective results (Calamel et al., 2010).

2.2. Forms of Collaborative Barriers

- Challenges to collaborative research can be summarized into four major areas namely; professional, administrative, ethical challenges and other challenges to individuals/institutions involved in collaboration with regards to the complication usually associated with collaborative research (CDD-Ghana, 2005).

2.3. Professional/ Expert /Connoisseur Barriers

- According to CDD-Ghana, (2005), some of the connoisseur barriers likely to affect research collaboration may comprise of; the difficulty in setting a common memorandum of understanding between partners to avoid them from disclosing sensitive discoveries of collaborative research outside the boundaries of collaborators; how to deal with the problems of collaborative projects funded by different donor agencies/organizations with varying conditions/criteria.

2.4. Administrative/Managerial Barriers

- This form of challenges comes either in a attempts to reduce competition within institutions specialized research, combined with collaborative research all competing for scarce resources of the organisation; share control of research procedures, i.e. from the conception stage to implementation and finally to the sharing of research outcome equally among collaborators. (CDD-Ghana, 2005; Zucker et al., 1996; Dok Yen, 2010).Also the possibility of ensuring that there is equality in decision-making among partners; again the challenge in partners complying with material transfer agreements; the difficulty of controlling sensitive information within the boundaries of collaborating organisational/institutions to outsiders, the risk of unintentional leaking of information to outsiders can have a great negative impact on the goals of the partnership; furthermore, the method of sharing the research output among partners resulting from the collaboration is a serious challenge especially where some partners feel they have inputted more than their share; again in instances where the final outcome of collaboration by researchers e.g. for the purpose of research, noncommercial purposes, nonprofit making organisations, etc.; moreover, some of the administrative difficulties usually includes the problems of who besides the collaborating partners may have the right to the usage of the final results/finding from the collaboration i.e. should it be limited to only individuals related to the recipient institutions or third parties should be included in the benefits; the kind of barriers to be imposed on the output of collaboration for publication e.g. The review of manuscript and legal authorisation by partners before joint publication with collaborative partners; the conflicting interest specially in educational institutes promoting staff on independent research and at the same time preaching on collaborative research (CDD-Ghana, 2005; Zucker et al., 1996; Dok Yen, 2010).

2.5. Ethical/Moral Challenges

- The other form of challenges can be described as ethical challenges and this usually also have to deal with issues such as; ensuring equilibrium among collaborating professionals, honesty and respect for both national as well as international rules and regulations guiding research projects; how to enable partners to develop trust among each other to adhere to professionalism; the problem of ensuring that associates have confidence among each other to hold on to professionalism, research protocols and financial issues without any form of unethical manipulation, misinterpretation of data; falsification, fabrication, inducement for data from subjects etc.; the difficulty of partners having to work together without really knowing each other's ethical standards and guides to research; how to ensure that effective measures are put in place to recognized and give credit to all the collaborators who have contributed both tangible and intangible to the research output; difficulty of ensuring that all partners within a collaborating team, win the confidence and trust of research subject by allowing them to work it at their own will without forcing them, subjecting them to harm, keeping their anonymity etc. throughout the research collaboration; how to make partners adapt to different cultural ethics and norms such as actions, words usage, gestures, etc. and sensitive to their subjects at different research sites (CDD-Ghana, 2005).

3. Methodology

- Academics from tertiary institutions that run postgraduate construction programmes in Ghana as at 2016 were sampled for this study. The Building Technology Department of KNUST-Kumasi was selected because they run MSc/MPhil/PhD in construction management and Building Technology, and also the Department of Construction and Wood Technology, University of Education, Winneba-Kumasi was selected as part of the sub-population sample for Academia because it also run’s MPhil Construction Technology and M. Tech.-Construction. These two were selected from the academia, because they are responsible for training and conducting higher level construction research works more frequent which can be applied or implemented in the construction industry. Therefore, they are in the position to make effective contributions to this research study. The sub-population sample of the industry consisted of corporate members of the Ghana Institute of Construction (GIOC) as part of this research, since this is the only professional body in Ghana that brings together all the professionals from across all sectors that are directly linked to the construction industry (such as; Quantity Surveyors, Architects, Construction Engineers, and so on). These are professionals who supervise the day-to-day construction activities in the Ghanaian construction industry. The logic behind the selected respondents was to ensure that the study has a representation of the major stakeholders in construction academia/industry that can make significant contributions to the aim and objective of this study.

3.1. Population Sample for the Study

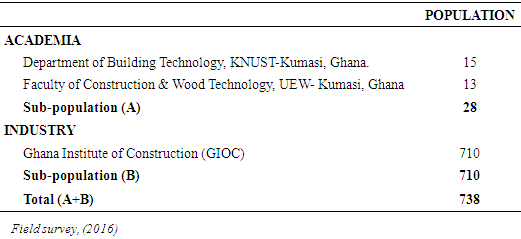

- Considering the nature of this research, the sample frame consisted of a population of practicing professionals such as professionals in the building construction industry (Quantity Surveyors, Architects, Engineers, and so on) and, practicing construction researchers such as lecturers in tertiary postgraduate institutions who run construction programmes in Ghana. The table 1 below is an illustration of the population of the academia and industry with a population of 28 and 710 respectively for the study.

|

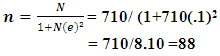

3.2. Sample Size

- This was designed in two forms as a representation of sample for both academia and industry as follows; All lecturers were capture for the of sample for the Academia because their population was small making it easy to capture all the population as a sample which represented 28 respondents, whiles Yamane formula was used in calculating the Industry sample size to 88 respondents. This resulted in a total sample of 116 respondents for academia-industry respondents for the study.Sample size calculation using Yamane formula

Where; N = Population sizen = Sample size e = Level of precision Note: considering a precision level of ±10% for this study @ confidence level 95% and p=0.5Yamane (1967)Total sample size = 28+88 = 116.

Where; N = Population sizen = Sample size e = Level of precision Note: considering a precision level of ±10% for this study @ confidence level 95% and p=0.5Yamane (1967)Total sample size = 28+88 = 116.3.3. Sampling Technique Adopted for the Study

3.3.1. Census Sampling

- This type of sampling technique was used to provide an opportunity for a level platform for all the professionals within the academic institutions selected for this research, who were only twenty-eight (28) respondents.

3.3.2. Systematic Random Sampling

- Systematic sampling technique was adopted for the data collection from the industry by selecting the first 6th member of GIOC members on the list of the GIOC cooperate members and every 6th on the list until the number of members was up to the required sample size needed for the study.

3.4. Design of Questionnaire (Sequence & Wording)

- The questions were designed such that, each was comparatively short, simple and easy for respondents to answer. They were structured to proceed in logical sequence moving in order of study for easy understanding to respondents of the content and also to make it easy for research analysis. The shapes of the questionnaire were designed such that twenty-seven (27) barriers to academia-industry collaboration, each had a rank from 1-5 using the Likert scale. They were ranked 1-5 with 1= not important 2=less important, 3= quite important, 4=important and 5=very important, as a means for brief direction for respondents to give their opinion by ticking one rank on each variable.

3.5. Mode of Questionnaire Administration

- The administering of questionnaires was done by mail with follow-up telephone calls to respondents who were distanced from the researcher as well as those who were too busy or it was difficult to get them face-to-face. The mailing enabled the researcher to cover a large number of its targets within the shortest period of time at a very low cost. A total of one-hundred and thirty (130) questionnaires were distributed to respondents; out of this one-hundred and two (102) questionnaires were sent to professionals in the industry and the remaining twenty-eight (28) questionnaires to the academician. Even though, one-hundred and sixteen (116) respondents were the target sample size set for this research, fourteen (14) extra was added to the respondents to run it up to 130 to make good for none return questionnaires, and also as a means of factor of safety to take care of the frustration and complexity in getting data from respondents based on previous similar studies.

3.6. Data Collected

- A total of seventy-nine (79) retrieved questionnaire were answered by respondents out of the one-hundred and thirty (130), sixty-three (63) from the industry and sixteen (16) from the Academia. Though the target returns were to use the systematic approach to work with the first eighty-eight (88) respondents from the industry data and all of academia, the retrieved responses unfortunately was not up to 88. Therefore, all the sixty-three (63) questionnaires from the industry, plus the sixteen (16) from academia were used for the analysis of this research.

3.7. Approach to Data Analysis

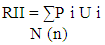

- The data was analysed using relative important index (RII) to come out with the most critical barriers to collaborative research among 27 variables in this section.The analysis for this study was to establish the relative importance index (RII) of the various factors identified as the barriers to academia-industry collaboration. The score for each factor is calculated by summing up the scores given to it by the respondents. The relative importance index (RII) was calculated using the formula below from a similar study.

| (1) |

4. Data Analysis

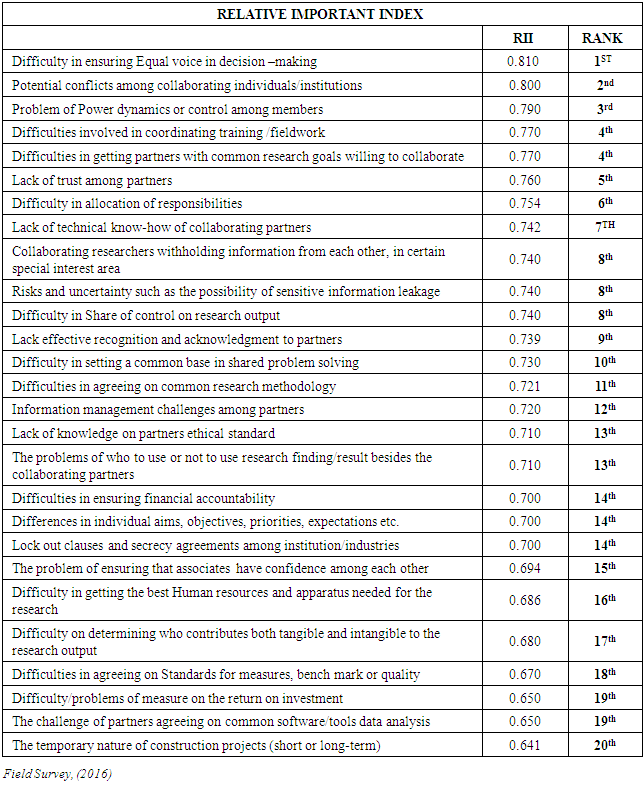

- The twenty-seven (27) barriers to collaborative research for academia-industry was examined, and ranked for the researcher to determine the most critical barriers from the respondents' point of view on academia- industry collaborative research. This was done using the Relative Importance Index (RII) and the results of the analysis were presented in table 2 below. Variables with RII < 0.599 were deemed to be insignificant as barriers to collaborative research therefore rejected from the table (Muhwezi et al., 2014). Also, variables were further considered to be critical or not where they were more than or less that average RII (0.73) from the 27 variables for the study. That is where RII ≥ 0.73 was considered to be critical whilst, all variables with RII < 0.73 were considered not critical barriers to collaborative research therefore were rejected.

|

4.1. Discussion on Barriers to Collaborative Research Analysis

- CDD-GHANA, (2005) opine the barriers to collaborative research in their study, as conflict resolutions arising from diverse missions of collaborating individuals/institutions such as academia-industry collaboration, where one partner mission stress on full exposure and publication of research output for academic training in contrast to the other partner desire to limit exposure owing to profit benefit of the market value from research findings. A study by Arvaja et al., (2007) also affirms conflicts generated during partnerships such as differences in the approaches to work as well as communication, the individual institutions/industry inclination reliance on others to work in share or contribution as well as the dynamics of power among members as barriers to collaboration. Also, CDD-GHANA, (2005), Dok Yen, (2010) and Adinyira et al., (2011), established that Equal voice in decision–making, barriers in locating partners with a common research agenda, sharing of research responsibilities, and the Possibility of conflicts arising in the course of collaboration among partner individuals/institutions were some hindrances to collaborative research. This study also, confirms Akintoye and Main, (2007) finding on lack of trust as a critical barrier to collaborative research. All though trust seems not to be the number one critical barrier from the RII scores, it can clearly be observed from the table 2 that trust is the most critical barrier to deal with for successful academia-industry collaboration. This is because out of the ten (10) critical barriers identified based on the average score of RII ≥ 0.73 it can be observed that three (3) different barriers all relates to trust issues that is; Lack of trust among partners RII (0.760). Collaborating researchers withholding information from each other, in certain special interest area RII (0.740) and the risks and uncertainty such as the possibility of sensitive information leakage RII (0.740).

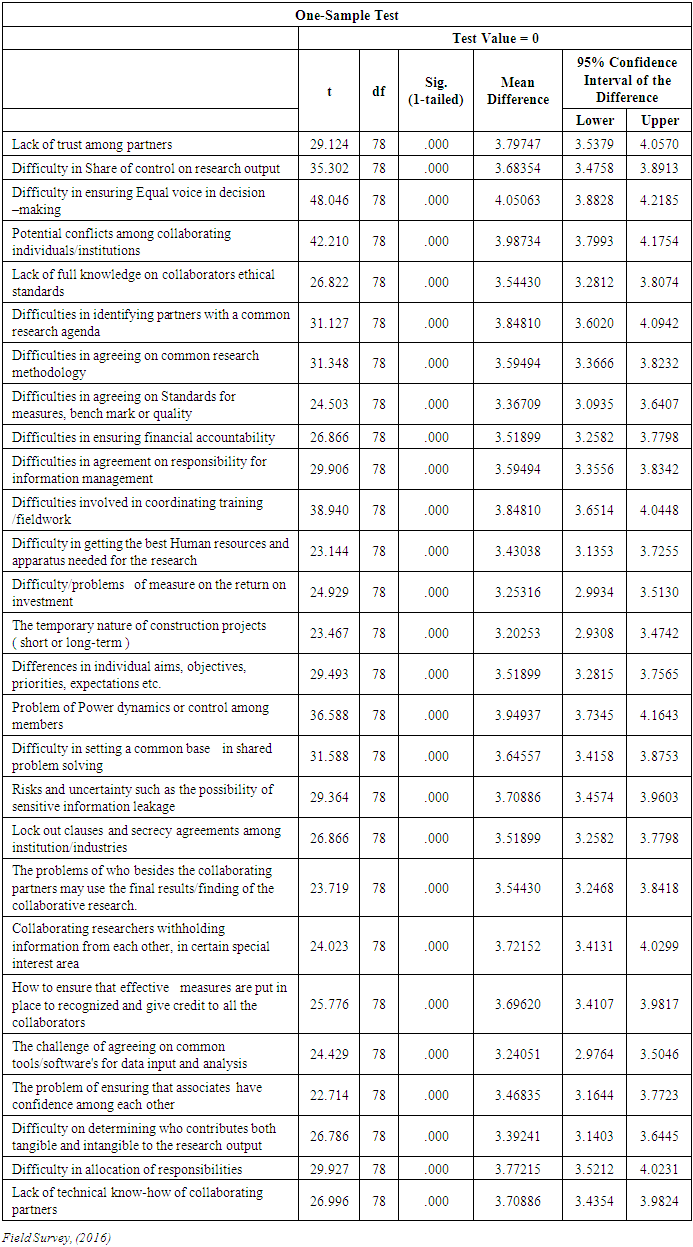

4.2. T-Test

- Also, further test was conducted on the data on the barrier to academia-industry collaborative research to establish whether the data was statistically significant for the study or not. The t-test table 3.0 presents the base values (that is, test value) of the population mean, t, indicating a one sample t-test, df, representing the level of freedom and the implication (that is, p-value). The p-value was used to determine whether or not the mean and the sample mean for the study for the data were statistically equal or corresponding. However, the p-value was divided into two because this study was interested in a single-tailed test, hence, the p-values for two-tailed test was simply divided for the single-tailed test. Yet still, all the variable under the barriers to academia-industry were deemed significantly fit for the study with sig. 000 (p< 0.001) for all the factors as can be seen in the table below.

|

5. Conclusions / Recommendations

- The main aim of this research was to establish the most critical barriers to academia-industry collaborative research in the Ghanaian construction industry. The Barriers were identified as; difficulty in ensuring equal voice in decision–making, potential conflicts among collaborating individuals/institutions, the problem of Power dynamics or control among members, difficulties in identifying partners with a common research agenda, and lack of trust among partners. This research finding provides an opportunity for academia-industry to come out with effective solution to overcome the barriers to collaborative issues within the academia-industry in construction research. The limitation of this study was the fact that all the authors for this study were from the academia. Hence, certain decisions were likely to be skew towards academia. Also, the Unequal number of respondents for both academia and industry was one of the major limitation to this study such that, the results of this study could probably have been influence by only the opinion of industry since they represented the largest respondents, and also because the analysis for the responses were not separated into academia and industry. However, since the respondents for industry was randomly selected there was a possibility to reduce that limitation. The researchers recommend that academia and industry should have regular dialogue and appraisal to come out with a collaborative framework that can address critical barriers to academia-industry collaborative research in the Ghanaian construction.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML