-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2017; 6(5): 215-220

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20170605.04

Awareness, Attitudes and Perception of Green Building Practices and Principles in the Zambian Construction Industry

Mutinta Sichali, Luke John Banda

University of Zambia, Department of Environmental Health, Lusaka, Zambia

Correspondence to: Mutinta Sichali, University of Zambia, Department of Environmental Health, Lusaka, Zambia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

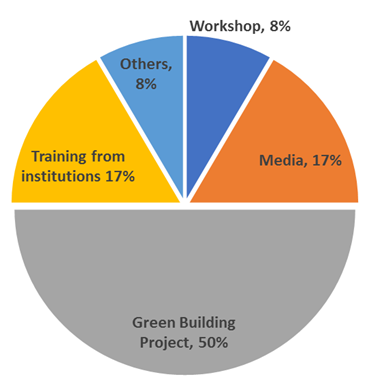

Awareness of green buildings technology is essential if practitioners in the building industry are to contribute in reducing negative impacts of building on the environment. Green building demonstration projects have been used as a way of sharing this knowledge to both practitioners as well as communities. Different strategies have been employed to share green building technology, however there is little research to demonstrate awareness attained from green building sites in Zambia. There are very few green buildings under construction and these few buildings could be a source of awareness. Understanding the level of awareness, perceptions and attitudes of artisans, communities and professionals on green building practices provides a good baseline on which to disseminate information on green building technology. This paper investigates the level of awareness, attitudes and perceptions of green building practices amongst participants in a green buildings housing project in North-Western and Lusaka provinces of Zambia. A qualitative descriptive cross sectional study was used and all the people who were directly involved in the project were interviewed. The findings suggest that the ones who had participated in other sustainability projects showed greater awareness than those who did not. The professionals had attained the knowledge from workshops, media, green building demonstration houses and institutions of higher learning while the artisans had attained it from previous project on renewable energy. Only two (2) community members showed great awareness which they attained from reading and watching documentaries on national television. The results suggest that professionals who were stationed on site demonstrated greater awareness than the artisans who spent an equal amount of time on the same project. The professionals showed the highest positive perception and attitude on the Likert scale. All the groups agreed that green building materials could only be affordable if they were locally produced. The study concluded that there are various ways of training practitioners on green building practices and no one method is sufficient. The sufficiency of the training depends on whether participants were made aware on the knowledge was being imparted. This should done at the beginning of the project. The demonstration houses showed that they could be a reliable source of training. Based on what the community said publications can be a good source of knowledge. For the professions, knowledge was acquired from university. This knowledge influenced their level of awareness and perceptions. The artisans who had worked on previous green building projects had gained knowledge. However knowledge gained was dependent on education levels. Training in green building practices should therefore be introduced in institutions of higher learning and trade schools.

Keywords: Green building practices, Energy efficiency, Sustainable construction

Cite this paper: Mutinta Sichali, Luke John Banda, Awareness, Attitudes and Perception of Green Building Practices and Principles in the Zambian Construction Industry, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 6 No. 5, 2017, pp. 215-220. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20170605.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The Zambian construction industry is one of the fastest growing industries in the Sub- Saharan region and the construction sector contributes 27.5 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of which the building industry is a part (Zambia invest. Magazine, 2014). Globally Buildings are responsible for 30 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions, 65 percent of waste output, 70 percent of electrical consumption and 12 percent of water consumption (National Energy Balance, 2009). Buildings which are not built in a green way can affect the health, safety, comfort and productivity of the occupants (Singh et al., 2010). Green building practices emerged after a United Nations conference held in Stockholm in 1972. The aim was to mitigate the impact of human activities on the environment and to improve the building construction process (Diana and Victor, 2012). Sustainable buildings can be a showcase to educate people about environmental issues, possible solutions, partnerships, creativity, and opportunities for reducing environmental impacts in our everyday lives (Diana and Victor, 2012). Green building, or sustainable design, is the practice of increasing the efficiency with which buildings and their sites use energy, water and materials, and of reducing impacts on human health and the environment for the entire lifecycle of a building (Abimbola, 2014). Knowledge or awareness as these words will be used interchangeably in this paper is the amount of information from participants on positive or negative environmental impact of buildings.

2. Research Methodology

- This was a descriptive cross sectional study and it used a qualitative method design. The research type was adopted from two similar studies by Usman and Khamidi, “Determining the Level of Green Building Public Awareness” and “Green Buildings: Analysis of State of Knowledge,” (2012) by Diana and Victor (2012). The studies carried out surveys to investigate the level of awareness about green buildings.

|

3. Data Analysis

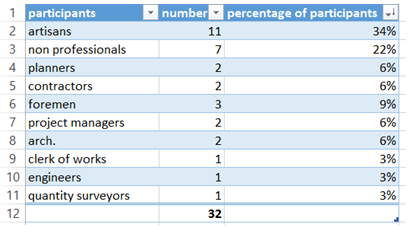

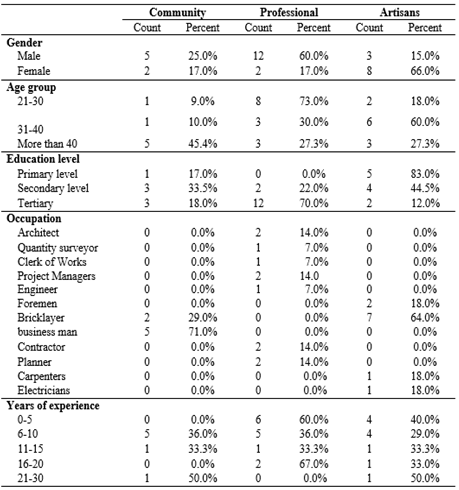

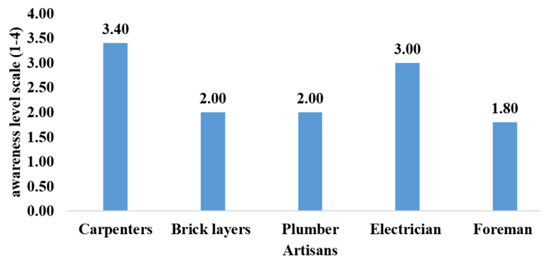

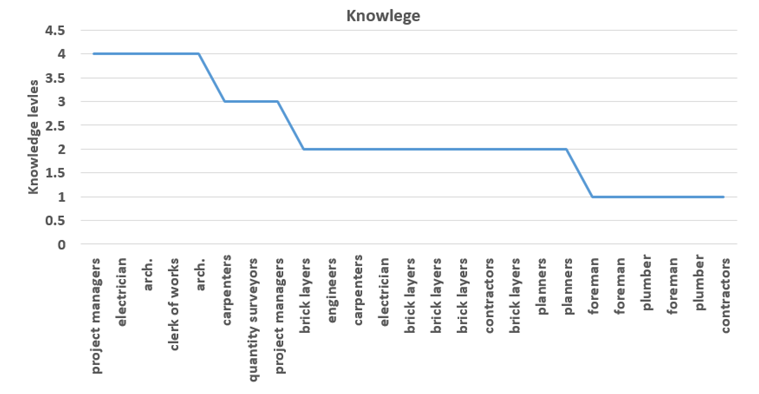

- The measure of green building awareness in this paper was based on rankings created on a Likert scale, A four (4) point awareness scale was used (1< very low, 2< low, 3< medium, 4< high). This type of ranking was based on a similar study that was done by Nazirah Z. et al. (2014). The data was generated from the awareness ranking scale that was created and mean scores were calculated for all participants grouping. The American LEED system was used as scoring chart. The following were the themes from which the questions were drawn: a) Sustainable site planningb) Safeguarding water and water efficiencyc) Energy efficiency, renewable energy and lower greenhouse gas emissionsd) Conservation and the reuse of materials and resources, and improved health and indoor environmental quality.The attitudes and perceptions were explored using a thematic analytical technique, where the themes were developed using categories based on participants’ responses and the resulting data (Fossey et al., 2002). The perceptions and attitudes helped explain the results that were seen in the awareness scale and these were measured on a Likert scale. The perceptions and the attitudes were scaled with 1- 5, with 1= strongly agree and 5=strongly disagree. A strong perception where it was expected meant a good attitude. The mean average was found for each group to see which group of participants had a good attitude and perception on green building technology.Table 2 presents summary results for socio-demographic variables of the study participants. The majority of the respondents were professional males (n=12, 60%). The largest number of females were artisans (n=8, 66%). The majority of the professionals (n=8, 73%) were aged between 21 to 30 years whereas (n=2, 18%) of the artisan were aged between 21 to 30 years and only (n=1, 9%) of the community members were in that age group. More than half of the professionals (n=6, 60%) had 0 to 5 years working experience, while the artisans with 0 to 5 years of experience were (n=4, 40%) and there were none of the community members with 0 to 5 years working experience.

|

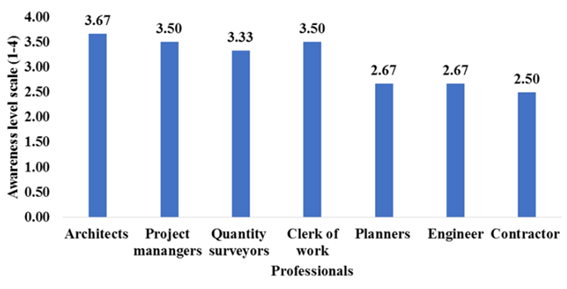

| Figure 1. Awareness level for the professionals |

| Figure 2. Awareness level for the artisans |

| Figure 3. Awareness level for all the participants |

| Figure 4. Sources of awareness on Green Buildings |

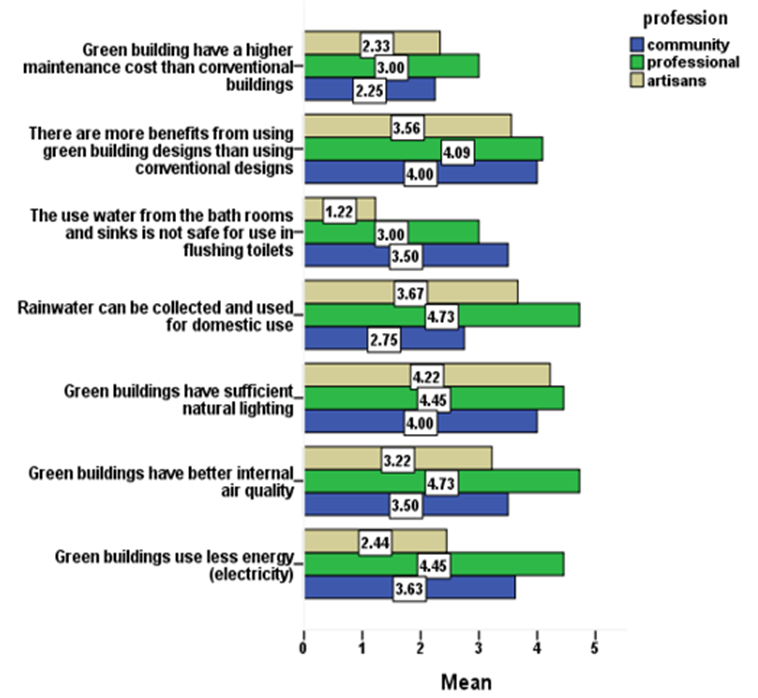

3.1. The Perception and Attitudes

- The perception scales ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree (5 point Likert scale). On the left side of figure 5, were questions that were asked in the questionnaire and the scale for each group presented. On average, the community and artisans disagreed that the maintenance cost of green buildings compared to conventional buildings is high. Professionals also disagreed but this was further explained that the maintenance cost on green buildings depended on the source of the building materials and the use of materials found within a local setting. Moreover, practically all three — the community, artisans and professionals agreed, with a mean score of about 4, that the benefits of using green building designs are greater compared to conventional ones. Further, only professionals strongly agreed (mean score of about 5) that rain water can be collected and used for domestic purposes whereas artisans only agreed (mean score of 3.7) and some community members were not sure (mean score of 2.8). The three grouping agreed that green building having sufficient natural lighting, each of the three groups sampled agreed.The community perception on the efficient use of energy in green buildings was low. This could be due to their low awareness of what energy efficiency meant. However the professionals were aware. There was a disparity in the community answers in that even though they disagreed that green buildings were energy efficient they strongly agreed that green buildings have better internal air quality and sufficient natural lighting. The participants were asked if rain water and grey water from the bath tub and sink could be reused for bathing and gardening respectively. All the professionals agreed that rainwater could be reused but the artisan’s perception over the use of grey water was negative (1.2 out of 6) while the community had the highest perception (3.5 out of 6). All the participants agreed that there were more benefits from using green building practices in buildings than conventional ones.When asked whether the materials were accessible and affordable all the groups were positive. When asked whether the green buildings concept was adopted from developed countries, they all strongly disagreed. The architects explained that if local materials were not used and foreign based materials were introduced then it would be a foreign concept. When asked if they would recommend green building technology all the participants agreed with a mean score of 4.5. When asked whether the demo houses were a good way of learning green building technology 80 percent agreed, while 10 percent thought workshops were the best and 10 percent thought a combination of workshops and demo houses would be the best way to learn.

| Figure 5. Perception of green buildings technology |

4. Conclusions

- The study concludes that even though the awareness levels among the artisans and the community were low their attitude and perception of green buildings practices was positive. There is need to increase awareness among all the participants and information should be made more available to all players in the construction industry and communities. The demonstration houses showed that they can be a reliable source of training. Prior knowledge gained from publications was a good source. The few who gained awareness had gained it through literature. The professional’s knowledge attained from University or Collaged had influenced their level of awareness and produced a good perception. The artisans who had worked on previous green building projects had gained knowledge but this depended on the level of education. Training in green building practices should therefore be introduced in institutions of higher learning and trade schools. The professionals felt that the introduction of green building practices in the building bye laws will institutionalise these practices. The demonstration houses aroused a lot of curiosity in the communities where they have been built and the introduction of green building technology was a welcome strategy. The actors in the building industry should be used as catalysts in the promotion of green building technology. More education is therefore required for the artisans and this should be by means of practical demonstration and not just theory. The professionals can go through continuous professional development, workshops and involving them in green buildings demonstration projects. The community could have community based education programmes where green building practices are demonstrated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author would like to acknowledge the University of Zambia, School of Public Health for the time given to carry out this study. Special thanks goes to the Journal club members at Sacore and the staff members of the department of Environmental Health. Further thanks go to the Lumwana community business association, Larfage Zambia and Kalumbila Housing Corporation where the study was carried out.

Limitations

- Carrying out a study of this nature on participants who had different educational levels put a limit to the study. The study is not representative of the whole construction industry and more cases of green buildings projects should have been included in the study to make definite conclusions. There will be need for further research on a bigger study population.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML