-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2017; 6(4): 168-179

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20170604.05

Towards a Saudi Plain Language Standard Construction Contract

Zeaid Mohammad Masfar

Master’s Degree, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Zeaid Mohammad Masfar, Master’s Degree, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This research addressed the possibility of adopting a plain language revision of the existing Public Works Contract of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It discussed the benefits of using plain language in legal documents. Literature indicates that plain language is communication that focuses on the reader; it presents information in ways that an ordinary person will easily understand. The relevant body of literature was reviewed and it was found that the proposed research had not been undertaken by any other published researcher. Through gathering relevant data using mixed methods and a well-crafted survey questionnaire, the preference of construction contract users was discovered. It was discovered that there is a high possibility of adopting a plain language standard term in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It is hoped the findings of this research will serve as a guide for the authorities in considering the adoption of plain language in the Kingdom’s legal system.

Keywords: Construction Contract, Saudi Public Works Contract, Plain Language, STCC-RSP

Cite this paper: Zeaid Mohammad Masfar, Towards a Saudi Plain Language Standard Construction Contract, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 6 No. 4, 2017, pp. 168-179. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20170604.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- “Words pay no debts, give her deeds: but she’ll bereave you o’ the deeds too, if she call your activity in question. What, billings again? Here’s ‘In witness whereof the parties interchangeably’ – Come in, come in: I’ll go get fire.”

- By William ShakespeareGone are the days when people speak in this way. Only a handful, such as those who appreciate art and those with philosophical minds, understand the above-quoted line. In this modern era simplicity in words is better. As Ameer Ali (2008) stated, if a more familiar style is surpassed by a new, innovative style, then the old, familiar style should give way. This article covers plain language in construction contracts and cites the Standard Terms for Construction Contracts for Renovation and Small Projects (STCC-RSP) with the hope of influencing the Public Works Contract (PWC) of Saudi Arabia.PWC and STCC-RSPThe monarchical system of government in Saudi Arabia is unique compared to other countries. The head of state is the King, who leads the national government and is, at the same time, the commander in chief of the military. Saudi Arabia does not have a legislated constitution or people’s constitution. Unlike other countries, who separate the Church and the State, the Saudi Arabian government rules on the basis of Islamic Law (sharia), the Qur’an, and Sunnah (records of sayings and actions of the prophet Mohammed); these are considered to be the Kingdom’s Constitution. As such, all statutes and other legislative output are called “regulations”.Considered the largest exporter of oil in the world, Saudi Arabia has a booming construction industry. Thousands of professional engineers, architects, and many other professionals from different countries migrate to work in this oil-rich Kingdom. Numerous contractors from different parts of the world have signed contracts with the government under the Public Works Contract (PWC), which regulates the nation’s construction contracts. Cowling (2011) stated the PWC was introduced in 1988 and is based on the International Federation of Consulting Engineers’ (FIDIC) Works of Civil Engineering Construction, 3rd edition (1977). The provisions of the PWC were drafted using traditional, legal language; most of its provisions are written in long sentences and paragraphs.In contrast to the Kingdom’s PWC, Malaysia, a country composed of 13 states, operates under a constitutional monarchy with a democratic system of government. Not so long ago, construction contracts in Malaysia, particularly for renovations and small projects, were awarded for particular purposes only (on ad hoc terms). Most of the awarded contracts lacked some material particulars, and some were made orally, thereby depriving the contracting parties of the benefits provided by the Construction Industry Payment and Adjudication Act (CIPA), an Act regulating the construction industry in Malaysia.In order to rectify this situation, the former president of the Royal Institution of Surveyors Malaysia, Dr. Noushad Ali Naseem Ameer Ali, authored the Standard Terms of Construction Contracts for Renovation and Small Projects (STCC-RSP). The STCC-RSP is unique, as it was written in modern, plain language. Using about 5000 words, this contract was the first construction contract in the world to be accredited with a clear English standard by the Plain English Commission in the United Kingdom.HypothesisIt was hypothesised that there is a possibility of adopting a plain language Standard Terms for Public Works Contracts in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In order to realise this possibility, a mixed methods survey was carried out to reveal the thoughts of the respondents; clauses from the STCC-RSP and PWC were compared quantitatively, as was a sample plain language clause with the original clauses of the PWC; finally respondents were able to provide a qualitative opinion on the hypothesis. All of the questions asked were for the purpose of moving towards a Saudi plain language standard terms for construction contracts.Research AimThe aim was to assess the views of individuals affected by the possibility of creating a Standard Terms for Construction Contract using plain language in Saudi Arabia. This aim was influenced by previous research findings, that the use of plain language in other law branches has produced significant benefits to the parties involved. Research Questions and ObjectivesThe aim focused on determining whether there was sufficient demand to move towards the creation of a Saudi Plain Language Construction Contract.Specifically, the research sought to answer the following:1. Whether construction contract users prefer a plain language construction contract or the traditional, legal language currently used in construction contracts?2. Whether plain language provisions increase users’ comprehension, as opposed to the traditional, legal language mostly used in construction contracts and other law branches?3. Whether the length of construction contract provisions affects users’ reading comprehension and the time spent understanding them?4. Whether the respondents would be willing to suggest (because it is a monarchy) to the authorities that the Kingdom should move towards the creation of plain language standard terms for construction contracts?The goal was to present a clear and concise comparison of similar clauses within the PWC and STCC-RSP, and compare the plain language PWC and the traditional, legal language PWC in order to determine the following:1. Which construction contract the respondents preferred overall; 2. Which construction contract the respondents preferred with reference to time spent in reading, their understanding or comprehension, and other matters affecting Construction Contracts;3. The possible reasons for preferring plain language or traditional, legal language;4. The views of the respondents regarding revising the traditional, legal language in order to transform it into plain language;5. The personal opinions of the respondents regarding ambiguity, complicated legal jargon, and cross-referencing of the original traditional, legal language of the PWC; and finally6. The possible existence of sufficient demand to move towards a Saudi Plain Language Construction Contract.

- By William ShakespeareGone are the days when people speak in this way. Only a handful, such as those who appreciate art and those with philosophical minds, understand the above-quoted line. In this modern era simplicity in words is better. As Ameer Ali (2008) stated, if a more familiar style is surpassed by a new, innovative style, then the old, familiar style should give way. This article covers plain language in construction contracts and cites the Standard Terms for Construction Contracts for Renovation and Small Projects (STCC-RSP) with the hope of influencing the Public Works Contract (PWC) of Saudi Arabia.PWC and STCC-RSPThe monarchical system of government in Saudi Arabia is unique compared to other countries. The head of state is the King, who leads the national government and is, at the same time, the commander in chief of the military. Saudi Arabia does not have a legislated constitution or people’s constitution. Unlike other countries, who separate the Church and the State, the Saudi Arabian government rules on the basis of Islamic Law (sharia), the Qur’an, and Sunnah (records of sayings and actions of the prophet Mohammed); these are considered to be the Kingdom’s Constitution. As such, all statutes and other legislative output are called “regulations”.Considered the largest exporter of oil in the world, Saudi Arabia has a booming construction industry. Thousands of professional engineers, architects, and many other professionals from different countries migrate to work in this oil-rich Kingdom. Numerous contractors from different parts of the world have signed contracts with the government under the Public Works Contract (PWC), which regulates the nation’s construction contracts. Cowling (2011) stated the PWC was introduced in 1988 and is based on the International Federation of Consulting Engineers’ (FIDIC) Works of Civil Engineering Construction, 3rd edition (1977). The provisions of the PWC were drafted using traditional, legal language; most of its provisions are written in long sentences and paragraphs.In contrast to the Kingdom’s PWC, Malaysia, a country composed of 13 states, operates under a constitutional monarchy with a democratic system of government. Not so long ago, construction contracts in Malaysia, particularly for renovations and small projects, were awarded for particular purposes only (on ad hoc terms). Most of the awarded contracts lacked some material particulars, and some were made orally, thereby depriving the contracting parties of the benefits provided by the Construction Industry Payment and Adjudication Act (CIPA), an Act regulating the construction industry in Malaysia.In order to rectify this situation, the former president of the Royal Institution of Surveyors Malaysia, Dr. Noushad Ali Naseem Ameer Ali, authored the Standard Terms of Construction Contracts for Renovation and Small Projects (STCC-RSP). The STCC-RSP is unique, as it was written in modern, plain language. Using about 5000 words, this contract was the first construction contract in the world to be accredited with a clear English standard by the Plain English Commission in the United Kingdom.HypothesisIt was hypothesised that there is a possibility of adopting a plain language Standard Terms for Public Works Contracts in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In order to realise this possibility, a mixed methods survey was carried out to reveal the thoughts of the respondents; clauses from the STCC-RSP and PWC were compared quantitatively, as was a sample plain language clause with the original clauses of the PWC; finally respondents were able to provide a qualitative opinion on the hypothesis. All of the questions asked were for the purpose of moving towards a Saudi plain language standard terms for construction contracts.Research AimThe aim was to assess the views of individuals affected by the possibility of creating a Standard Terms for Construction Contract using plain language in Saudi Arabia. This aim was influenced by previous research findings, that the use of plain language in other law branches has produced significant benefits to the parties involved. Research Questions and ObjectivesThe aim focused on determining whether there was sufficient demand to move towards the creation of a Saudi Plain Language Construction Contract.Specifically, the research sought to answer the following:1. Whether construction contract users prefer a plain language construction contract or the traditional, legal language currently used in construction contracts?2. Whether plain language provisions increase users’ comprehension, as opposed to the traditional, legal language mostly used in construction contracts and other law branches?3. Whether the length of construction contract provisions affects users’ reading comprehension and the time spent understanding them?4. Whether the respondents would be willing to suggest (because it is a monarchy) to the authorities that the Kingdom should move towards the creation of plain language standard terms for construction contracts?The goal was to present a clear and concise comparison of similar clauses within the PWC and STCC-RSP, and compare the plain language PWC and the traditional, legal language PWC in order to determine the following:1. Which construction contract the respondents preferred overall; 2. Which construction contract the respondents preferred with reference to time spent in reading, their understanding or comprehension, and other matters affecting Construction Contracts;3. The possible reasons for preferring plain language or traditional, legal language;4. The views of the respondents regarding revising the traditional, legal language in order to transform it into plain language;5. The personal opinions of the respondents regarding ambiguity, complicated legal jargon, and cross-referencing of the original traditional, legal language of the PWC; and finally6. The possible existence of sufficient demand to move towards a Saudi Plain Language Construction Contract.2. Review of Relevant Literature

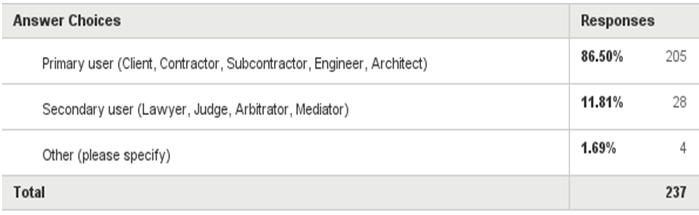

- In order to begin determining if the hypothesis could be realised, relevant literature pertaining to plain language was reviewed. The review included the history of plain language; its definition; its advocates; the process of writing plain language in documents, sentences, and the active voice; writing plain language in legal documents; its relation to legislation; its relation to construction contracts; the sources of construction conflicts; its advantages and disadvantages; solutions proffered by previous studies; and gaps in the literature.History of Plain LanguageAccording to Peter Tiersma (2007), author of “The Plain English Movement”, while the specific origin of plain language is unknown, the modern movement for plain language started in the 1970s. For many centuries, people have objected to the obscurity of lawyer’s language; Tiersma (2007) stated that the first major struggle in England was to make legal text English, instead of Latin or French. When William, Duke of Normandy, became King of England by defeating the Anglo-Saxon king Harold in 1066, King William and his constituents continued to use Latin and French in their legal documents. England continued to use the French language in their legal documents for over three hundred years, even though the English population at that time no longer spoke French. In order to resolve the situation, the English Parliament passed the Statute of Pleading in 1362. This first plain English law required that all pleas use the “English Tongue”. Despite the enactment of the plain English law, the peculiarities of the language used by the English legal system did not vanish; instead, the style continued to persist. From the early 1970s up to the present numerous authors and plain language advocates have criticised the legal language. Today, numerous Web sites exist that help promote the use of plain language. All these sites encourage the use of plain language in documents used by governments, businesses, and organisations. Definition of Plain LanguageThe absence of a standard definition for plain language prompted plain language advocates to form their own definitions. Garner (2001) stated that plain English can be achieved by using the simplest and most direct way of expressing an idea, avoiding fancy words that have everyday replacements but mean exactly the same thing. Asprey (2003) said that although plain language is equated with simplicity it does not mean it is simplistic. He stated it can be dramatic, elegant, or beautiful as long as it is straightforward, clear, and in line with the needs of the reader.Butt and Castle (2006) stated that the essence of plain language is to write clearly in order for it to be effective for its intended audience. Eagleson (2010) added that writing should be straightforward and avoid obscurity, inflated vocabulary, and convoluted sentence structures, using only the most necessary words. Collins (2005) referred to plain language as “effective communication”. Authors like Cutts (1995) did not specifically define plain language but described it as “The writing and setting out of essential information in a way that it gives a co-operative, motivated person a good chance of understanding the document at first read, and in the same sense that the writer meant it to be understood”. Kimble (1994) stated that plain language has to do with clear and effective communication - nothing more or less.Some proponents of plain language have discussed creating specific drafting standards. Mazur (2000) stated that instead of a formal set of rules promoting plain language, the focus should be on guidelines in order to allow the author freedom in the manner of presenting information to the reader. Not everyone agrees with the creation of guidelines, with Redish (2008) suggesting the creation of a generic definition of plain language is enough.Advocates of Plain LanguageMasson and Waldron (1994) stated that the primary motivation in insisting on the use of plain language is to increase comprehension among non-experts. They asserted that efforts to promote clarity in communication began as early as the seventeenth century, when scientists showed concern about aspects of speaking and writing that were difficult to understand, rather than clarifying the explanation of ideas. Masson and Waldron are clearly opposing Penman’s (1993) earlier argument that there is no hard evidence that plain language improves comprehension. Penman claimed that litigation cannot be reduced by plain language because interpreting words is the very essence of law. Penman’s (1993) had also stated earlier that using plain English is not the right solution to the problem of understanding documents. In criticising Penman, Kimble (1995) cited numerous study findings showing that plain language increases comprehension. Noteworthy of such findings was that of Charrow and Charrow’s (1979) study, which concluded that comprehension improved from 31% to 59% when they presented oral, plain language jury instructions to jurors.Brockman (2004) stated that in advocating plain language, people at the top, for example government leaders and legislators, must sponsor and support the move for plain language, continue reviewing plain language strategies, and learn from others. Valdovinos (2010), speaking on plain language advocacy in Mexico, said that every country that introduced plain language benefited from early institutional support. He further stated that advocacy remains vital for strengthening plain language throughout the world and in order to realise the potential that plain language offers to the public and economy, countries already engaged in plain language should share their success with others.Tiersma (2007) advocated using guidelines and an objective evaluation measure. He claimed that complexity is what really matters so he suggested focusing on factors such as sentence structure, levels of embedding, and likelihood that the average person will understand the meaning of the word.Writing in Plain LanguageBalmford (2005) stated that plain language should apply to an entire document, which includes its content, language, and structure, as well as its design. Authors should focus on the primary reader and the reason for communication – this would result in plain language. Bivins (2008) supported this, stating that the purpose of a document is to impart information to its audience. Plain Language SentencesBerry (2009) explained that difficulty understanding legislative documents is due to long and complex sentence structures that surpass the cognitive capacity of a person’s short-term memory. Ameer Ali agreed with Berry, stating that the best way to reduce the average number of words per sentence was to break up long sentences into short ones and one way of doing this is to use bullet lists and numbers, which can also make writing more presentable. Painter (2005) suggested that the average sentence length should be composed of 18 words. Plain Language. Gov (2007) stated that complexity is the greatest enemy of clear communication. A sentence should express only one idea. Readers are easily distracted by sentences containing dependent clauses causing them to lose focus on the main point. Plain Language in the Active VoiceBivins (2008) said that a document should be written in the active voice because it is easier to understand: the subject of the sentence is performing the action in contrast to the passive voice, where the subject receives the action. Despite this, Bivins (2008) accepted that the passive voice may be beneficial in some situations because it can eliminate sloppy sentence structure and provide variability within a paragraph. Plain Language in Legal DocumentsPlain Language. Gov (2007) described traditional legal writing as wordy, full of overlong sentences, and unnecessarily difficult to absorb. The Parliamentary Council Office of New Zealand’s document “Principles of clear drafting”, states that there are three key areas to consider when planning a draft. These are: the objective, which involves identifying the thing that the writer is drafting, for example a Bill, Part, or Section; the framework, which involves the conceptual structure; and the order, which involves the arrangement of material into logical order. Moran (1999) stated that in drafting a statute in plain English, the drafter needs to deal directly with the issue. A drafter should strive for precision and legal effectiveness as well as for intelligibility. Cross referencing cannot always be avoided, but it can be limited - clarity should be the priority instead of brevity (Ameer Ali, 2008). Crowding a document with definitions is one form of cross-referencing because the reader would be forced to leave a clause they were considering and go to the definition to discover the meaning of a particular word (Eagleson, 1999).Most legal documents make use of topic headings. Plain language advocates promote the use of question headings over other types of headings (Plain Language. Gov, 2007) as these can forestall a reader’s question. Bivins (2008) agreed with this: “Informative headings not only give the readers a brief summary of information in each section. They help reveal a document’s organization to readers as well” (p.10). A reader can obtain a brief outline of the document by merely looking at the headings.Plain Language in Relation to Legislation Plain language in legislation can both increase readers’ understanding and reduce government’s time resources (Byrne, 2008). In relation to drafting, Barnes (2006) identified that the cause of “incomplete statutes” originated from a poor drafting style adopted in legislation. Albert Einstein famously said “Make everything as simple as possible but not simpler”; likewise a legal document should be drafted or revised in plain, simple, and clear language without ignoring legal correctness (Ameer Ali, 2008).Plain Language in Relation to Construction ContactsConstruction contract users can be categorised into two, basic groups: primary users, those parties and signatories of the construction contract; and secondary users, those who are obliged to defend the parties, to judge the contract, or those who will interpret the contract should it be challenged (Ameer Ali, 2008). To simplify communication a writer should avoid words with multiple meanings (Garner, 2001). Ameer Ali (2008) agreed with Garner by citing the example of “Standard Conditions of Contract”. “Conditions”, in this instance, can have a double meaning. A condition may be a condition in the legal sense, by which a violation of such may entitle the offended party to repudiate the stipulation or the whole contract itself. However, a condition may also mean a mere warranty that a breach will only entitle the offended party to claim for damages.Advantages and Disadvantages of Plain Language Heraclitus, a great philosopher, once said, “The only thing that is constant is change”. Toto, an Italian actor and poet, likewise said “The only permanent thing in this world is change”. In plain language, not everyone agrees. Kelly (1999) concluded that using plain English was far more difficult than talking about it. He feared that plain English enthusiasts who concentrated on word substitution might underestimate the difficulties involved in simplifying complex legal documents. On the contrary, Palyga (1999) concluded that good, plain English is more precise than legalese because the meaning becomes more transparent. Butt and Castle (2006) suggested that redundant words could be omitted, for example, the words “null and void” because void alone will suffice. Likewise, Wydick (2005) stated that lawyers’ use of outdated and arcane phrases in the legal profession makes their communications verbose and redundant.Penman (1993) believed that litigation would occur whether legalese was present or not because, according to her, interpretation is the very essence of law. Kimble (1995) disagreed because he believed that by preventing the unnecessary confusion that traditional legal writing produces, plain language could reduce litigation. Jones (1998) admitted that legalese, a form of jargon used by the legal profession, is an important component of legal language. However, he objected to it when extreme forms of jargon predominated a legal text because it obstructed communication. Sometimes even legal professionals encounter comprehension problems with jargon, however this is more the case with laymen (Jones, 1998).Pollman (2002) stated that jargon is beneficial because it gives the legal community a common language that enriches their communication, however she admitted that jargon causes comprehension problems in legal writing. Crump (2002) asserted that plain language legal writing can disrupt established convention and may cause confusion. Phillips (2003) agreed, stating that there is reason enough to justify the use of special, legal language, and an attempt to make it plain will decrease both the consistency and precision of the law that plain language enthusiasts attempt to simplify. The use of plain language in legal documents will benefit not only the public, but the legal profession (Tiersma, 2007). Since statutes affect public interest directly by conveying rights and obligations, the public should understand them without the need for an interpreter.Solutions Proffered in Previous StudiesPrevious studies, in relation to advocating plain language, have suggested that all those who adopt plain language should cooperate to share their success with others (Martorana, 2014). It is clear that support from officials is needed and a continuous review of plain language strategies should be made (Brockman, 2004). Institutional support, according to Valdovinos (2010), is also needed to ensure the movement for plain language law drafting or revisions is maintained. Researchers have proffered many more suggestions but these have already been discussed, above, in this literature review. To include them here will cause ambiguity in writing this literature, which is one of the issues this research proposes solving.Gaps in the Existing LiteratureThe literature cited above explained the positive and negative aspects of plain language. Some authors explained the benefits that can be derived from drafting statutes and construction contracts using plain language, while others focused on the proper way of revising an existing statute or construction contracts. Most construction contracts drafted in plain language are newly formulated contracts, not revisions or amendments. Despite the abundance of literature pertaining to plain language, there is no direct data relating to the possibility of revising the voluminous Public Works Contract (PWC) of Saudi Arabia, nor any research showing what the primary and secondary users of construction contracts prefer. This literature review has validated the need for additional research in understanding user preference, along with the possibility of adopting a revised plain language PWC for Saudi Arabia.

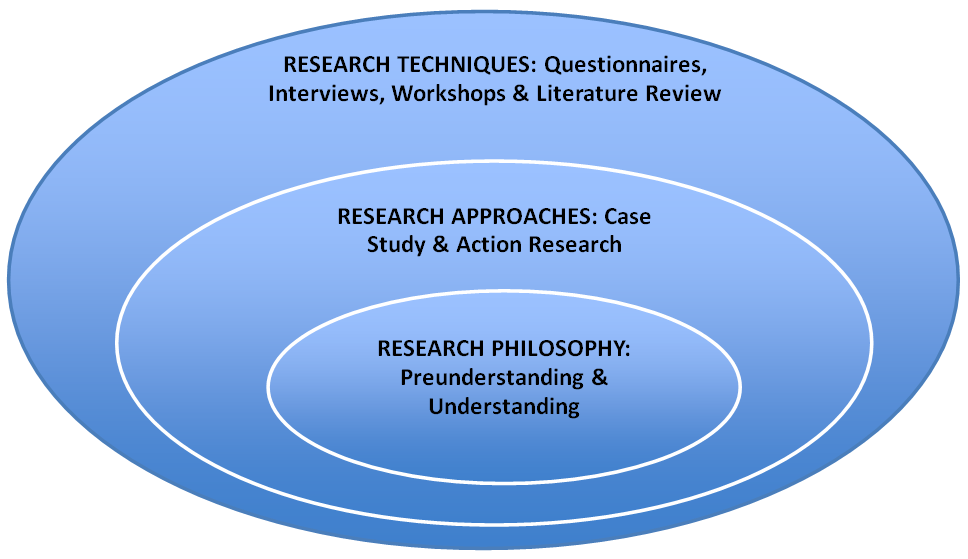

3. Methodology

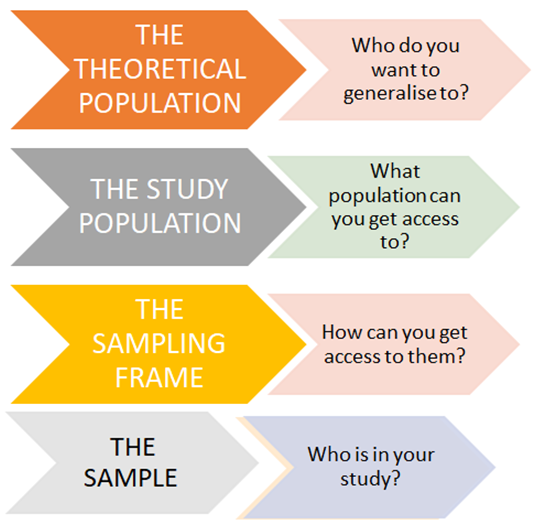

- In order to prove the hypothesis, the “Nested Model” was utilised; Kagiolou, Cooper, Aouad, and Sexton (2000) divided this into three divisions namely: the research philosophy; the research approach; and the research technique/s. Figure 1, below, shows the Nested Model.

| Figure 1. Nested Model |

| Figure 2. Process of Obtaining Research Sample |

4. Findings / Results

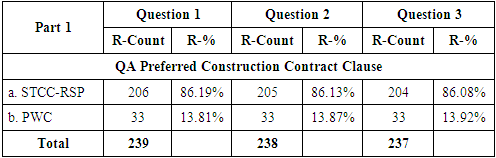

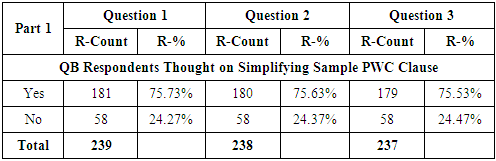

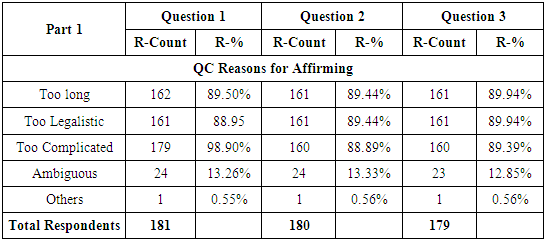

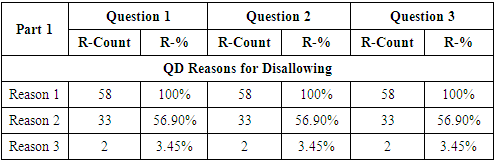

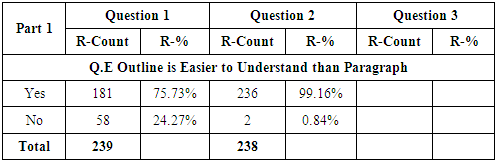

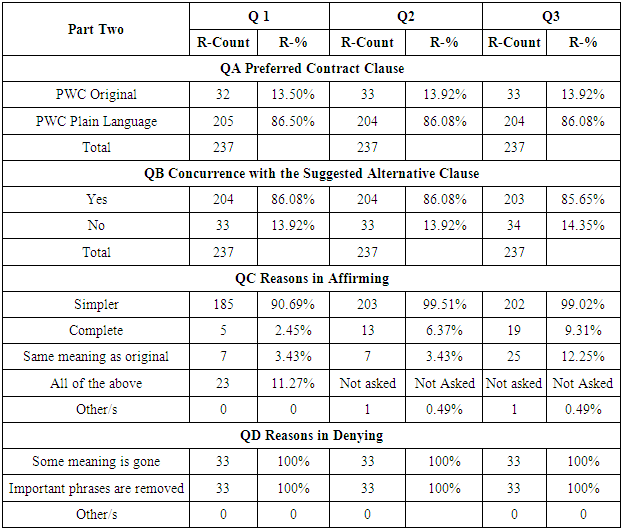

- Part 1 of the questionnaire was composed of three questions comparing the PWC and STCC-RSP. It suggested a promising result, as shown by Table 1 below.

|

|

|

|

|

|

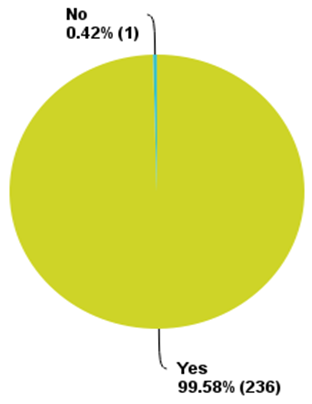

| Figure 3. Number of participants who had entered into a construction contract |

|

|

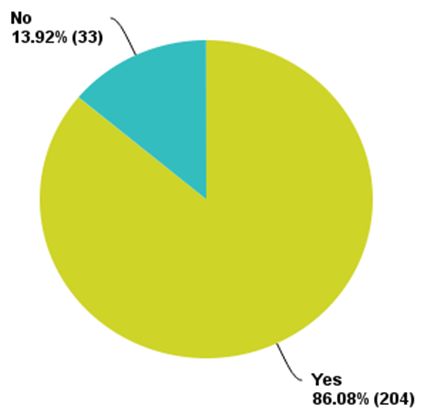

| Figure 4. Length of a contract clause affects respondents’ reading comprehension |

5. Conclusions

- The results of this study clearly revealed that there is a strong will and sufficient support to move towards a Saudi plain language construction contract. Based on the results, it appears that there is a sufficient demand for an amendment or revision of the current Saudi Arabia PWC. Clearly, there is a strong support for plain language from the primary and secondary users of construction contracts.This study revealed that the majority of users of construction contacts prefer plain language. The results of this study are evidence enough that construction contract users prefer a plain language construction contract to streamline their understanding of their duties and responsibilities and avoid conflicts, which require large monetary expenses, either on alternative dispute resolutions or through court action.

6. Further Study

- Recommendations for ImprovementsIt is recommended that to improve this study, additional topics could be covered, for example, legal jargon, plain language sentence construction, wordiness, redundancy, conjoined phrases, and poor word choices. Sample plain language suggestions should leave no room for error through ensuring the suggestion is complete without diverting from the original meaning of the clause being revised. For researchers with a large budget, an increased number of participants would be recommended. There should also be an increased number of clause comparisons between the plain language suggestions and the original clause. A comparison with two or more plain language contract terms of other countries is also recommended.Recommendations for Further StudyFuture study should focus only on the views of secondary users to know their exact stand on plain language vis à vis legal language. It is recommended that future researchers draft a complete plain language revision of the current PWC and present it by way of a quantitative questionnaire or qualitative interviews to primary and secondary PWC users.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML