-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2017; 6(4): 133-147

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20170604.02

Occupiers’ Maintenance Initiatives in Government Owned Housing Units in Dar es Salaam Tanzania

Arbogasti Isidori Kanuti, Samwel Alananga

Land Management and Valuation, Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Correspondence to: Arbogasti Isidori Kanuti, Land Management and Valuation, Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Throughout Tanzania, public housing units are in poor state of repair and maintenance in both rental and institutionalised estates. Among the highly dilapidated houses are those built within University campuses. This study present results from a survey conducted using 72 questionnaires, of which 22 were administered to occupiers of government houses at the Ardhi University (ARU) and 50 at the University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM) in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Secondary data were also requested from the Estate Managers of the two universities. Based on the results of binary logistic regression models which were used to predict the probability of house building condition improvement in response to occupiers maintenance initiatives, it was observed that occupiers’ maintenance initiative significantly improves building condition but such improvement is biased towards structural defects rather than facilities. An occupier undertaking maintenance initiatives has 89 percent chance of improving the overall building condition above average than if she/he did not. Occupiers’ initiatives are however biased in favour of accommodative rather than adaptive maintenance and there is limited creativity in occupier’s maintenance strategies. Given the meagre budgetary allocation for maintenance of housing units in the two universities, this study recommends for mainstreaming of occupiers initiatives so that they can be compensated when public funding is available. A monetary compensation could be the most effective means of encouraging owners’ initiatives towards maintenance of public housing. However, other forms of compensation may be sought as well.

Keywords: Tanzania, Public housing, Maintenance, Structural defects, Facility defects, Occupiers’ maintenance initiatives

Cite this paper: Arbogasti Isidori Kanuti, Samwel Alananga, Occupiers’ Maintenance Initiatives in Government Owned Housing Units in Dar es Salaam Tanzania, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 6 No. 4, 2017, pp. 133-147. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20170604.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- As a form of housing tenure, public housing refers to the housing units that are partly or fully owned by the government. These houses may be provided by government agencies or institution to support low income households, employees or any other marginalised groups. A typical feature of all public housing is subsidised housing cost in the form of non-payment of rent and housing support programmes. Maintenance of these houses is a global concern because most of them achieve a lower maintenance than private sector houses (Cobbinah, 2010; Lau, 2002; Matindi, 2013). Gahlot (2006) observes that 85 per cent of the 5 million council houses in India were in need of repair and improvement while in the Netherlands, the central government left the responsibility of maintenance to property owners and local authorities (LAs). Similarly, in Kenya, Matindi (2013) observes that public houses in Nairobi were not frequently maintained and did not remain in good order. Likewise, public housings have suffered lack of maintenance which is a manifest feature in all major urban centres in Tanzania (Komu, 2011). Olusola et al., (2016) argue that public housing buildings in Nigeria are left with poor maintenance despite massive expenditure spent when constructing them. As a result of these shortcomings in the provision of public housing units, critics have argued along sustainability grounds and advocated for market policies towards the provision of housing (Lau, 2002).The maintenance task is often seen by the management as an avoidable one since it is perceived as adding little to the quality of the working environment (Olajide, 2012). The current approaches to maintenance in many public housing do not empower occupiers to own the maintenance task and initiate the process. Most public institutions (controlling public houses) tend to place undue emphasis on outsourcing the maintenance aspect of their functions, instead of empowering their in-house maintenance institutions (Komu, 2011; Ho & Gao, 2013). Despite this neglect of inhouse capabilities, staff house condition and its environment is an indicator of the level of development and condition and even the quality of services offered by those occupiers to their parent organisation (Mwita & Yan, 2011; Olusola et al., 2016). As observed by Mkilania (2016), a poor quality living accommodation will impact negatively on the physical and mental health of the residents of a housing estate.Despite the Governments’ efforts to raise the performance of public housing, little emphasis is placed on staff houses maintenance (Mkilania, 2016; Matindi, 2013). Expenditure on repair is sometimes too huge to accommodate that many public institutions find it unbearable (Cobbinah, 2010). Inadequacies in the current approaches to public housing maintenance have contributed to poor service delivery, unnecessary increase in maintenance costs and low users’ satisfaction (Olanrewaju & Abdul-Aziz, 2015; Jolaoso & Oriola, 2012). Ibem (2012) has also proposed that repair and maintenance of public housing is one of the most challenging elements of the public housing service. It is common to find public housings being in dilapidated and in extreme cases beyond repair (Komu, 2011), not efficiently maintained (Ammar et al., 2012), maintenance expenses are not prioritised in financial accounts (Matindi, 2013) and fewer financial resources are allocated to them (Abd-Wahab et al., 2015; Suffian, 2013; Cobbinah, 2010; Matindi, 2013). Generally, maintenance problems arises from poor maintenance management with respect to current approaches to public housing maintenance in developing countries. Therefore, the idea of maintenance must be considered from the occupier/user rather than from external perceptions or factors related to the mechanics involved. That notwithstanding, there is limited research based evidence rationalising a need to deviate from the current seemingly mechanistic and inward-looking approaches towards a holistic maintenance approach which promotes diversity. That is the very fabric upon which this study is founded.

2. Maintenance Theory and Approaches

- The theory of maintenance advanced by Syagga & Malombe (1995) compares housing maintenance with care and treatment of a patient in hospital. As a patient needs light treatment for light injuries, so do buildings that need repairs for minor defects; as the patient need intermediate care in pre and post-operative situations, so do buildings that face less serious but major defects; as the patient become serious and in need of intensive care, so is the building that requires continuous maintenance and detailed monitoring. This maintenance theory advocates for maintenance planning encompassing both incidental and planned maintenance activities (Matindi, 2013). Stewart (2003) indicates that, maintenance involves both repair and improvements (installing something new in the house).

2.1. Approaches to Building Maintenance

- Maintenance has been classified into planned and unplanned (Cobbinah, 2010). Planned maintenance is carried out with forethought, control and the use of records to a predetermined plan (Olanrewaju & Abdul-Aziz, 2015). It is concerned with intervening in the life cycle of a building immediately before it can be expected to cause problems (Newman, 2001). Planned maintenance is further grouped into preventive and corrective maintenance. Preventive maintenance is carried out at predetermined intervals under prescribed criteria and is intended to reduce the probability of failure or the performance degradation (Matindi, 2013). It may include minor repairs involving replacement of parts and cleaning to major rehabilitations carried out in line with preventive maintenance procedures that are incorporated into a building’s operational guidelines. This approach reduces the probability of failures or breakdowns before they emerge and can aid in the detection of any existing malfunction before it becomes serious (Cobbinah, 2010). Preventive action need to be incorporated as early as planning or design stage of the building (Matindi, 2013).Variants of preventive maintenance include predictive and pro-active maintenance (Olanrewaju & Abdul-Aziz, 2015). Predictive maintenance represents the degree of planned maintenance where technology is employed to determine or detect trends that indicate excessive wear whilst; pro-active maintenance is a highly structured practice that uses information from analyzing equipment to identify origins, not just symptoms, of equipment problems (Cobbinah, 2010). However, this practice is more suitable for specialised building elements (Waithanji, 2005). It is most suitable in the manufacturing industry as compared to the building and construction sector (Ashworth & Hogg, 2002).On the other hand, unplanned or corrective maintenance is a type of maintenance that is necessitated by unforeseen breakdown or damages also called unexpected and unavoidable maintenance. Corrective maintenance is also termed as emergency or normal response to a failure or breakdown (Ashworth & Hogg, 2002). Corrective maintenance is what is generally referred to as repair. It is often initiated as a result of lack of maintenance culture, whereby a building or its parts are allowed to fail before maintenance is initiated. Corrective maintenance is done to restore the building into its normal condition. It entails the repair, servicing and replacement of any worn out, defective or broken parts, including the cutting-off of any decaying or crumbling components of a building. It should be noted further that public housing maintenance is principally corrective (Au-Yong et al., 2016).

2.2. Rationale of Public Housing Maintenance

- The foregoing discussion on maintenance typologies has pointed that house building condition at any point in time depends on a number of determinants such as frequency of maintenance to achieve timely maintenance schedules and avoid further deterioration (Au-Yong et al., 2016); the maintenance approach where the nature of work, quality, cost, and size must be incorporated (Olusola et al., 2016); The scope of maintenance schedules as embedding the results of past experience; and performance of similar facilities (Au-Yong et al., 2016). Apart from laxity in maintenance approaches, pressure on the use of public facilities may result into deterioration of the floor, wall, window, door and the electrical gadget such as sockets, switches and plugs (Cobbinah, 2010). Many maintenance problems in relation to facilities emanates from use, location, ventilation and number of users (Ibem & Aduwo, 2013). Olayinka & Owolabi (2015) observe that there is a significant relationship between performance of houses and the overall condition of the houses. There is evidence, however, that the building performance has been weakly linked to physical condition of facilities (Ishiyaku et al., 2016). Therefore, apart from physical condition, the number of users of the facility could also be a real problem faced in public housing maintenance (Ishiyaku et al., 2014). Yusofa et al., (2012) observes that adequacy of social infrastructural facilities significantly contributes to public housing satisfaction with the exception of damaged painting. The condition of dining area, quality of roof, air conditioner and hand wash basin and wash waster closet are also significantly associated with the overall performance of the building (Ishiyaku et al., 2016).Different housing types tend to have different perception among occupiers because of the associated maintenance requirement in each (Jiboye, 2013). In privately owned apartments for example, it has been observed that the issue of management of shared areas are of critical concern (Lau, 2002; Lam, 2008). This is because the management of shared space such as the entrance lobby, corridors, staircases, elevators, pumps, and drainage downpipes is challenging because of the need for cooperative behaviour among co-owners (Yau, 2012). The maintenance complexity of multi-storey apartments is further compounded by maintenance cost if such cost is to be recovered through occupiers or tenants fee. Most often, these occupiers and tenants fail to pay the requisite fee (Abd-Wahab et al., 2015; Lam, 2008). Single detached housing units have been observed to be less problematic as far as maintenance management is concerned (Lau, 2002). Therefore, maintenance initiatives must be stipulated at the design stage through specification and selection of suitable materials, appropriate designs, recommendation of good standard of workmanship and anticipation of future maintenance needs by the architect during the design stage (Matindi, 2013).

3. Occupiers’ Maintenance Initiatives in Public Housing

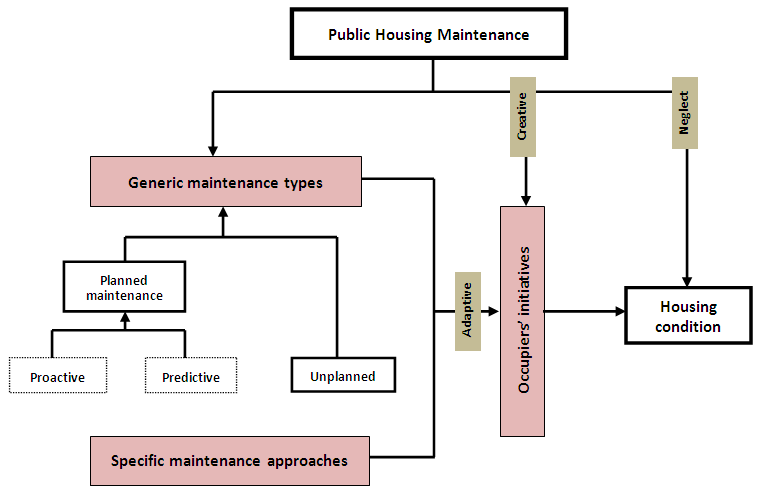

- According to Ali et al., (2010) participatory maintenance approaches incorporates tenants in decision-making processes and create an environment where occupiers take the rights of the housing facility and subsequently become responsible for the operational and maintenance of the facility. Furthermore, Yeboah-Assiamah (2015) notes that public housing maintenance is not the responsibility of the government alone; to a certain extent it requires the combined efforts of all concerned parties. Maintenance of public housings should be planned for and catered for in any tenancy agreements, while clearly outlining the party responsible for the maintenance, the areas as well as the scope of maintenance (Waithanji, 2005). Figure 1 provides a schematic view on occupiers’ involvement and their potential contribution towards improvement of the condition of building or facilities associated with the building.

| Figure 1. Conceptual model of occupiers’ maintenance initiatives in public housing |

3.1. Occupiers’ Creative Maintenance Initiative

- Public housing occupiers are the primary initiators of maintenance action and they influence the amount of maintenance work undertaken. Harrison (2004) shows that better informed occupiers can play a constructive role in linking the estate office and the occupied building. Without occupiers’ formal maintenance participation arrangements, informal occupiers’ initiatives towards housing maintenance of occupied units reflects the extent at which housing attributes, services and surrounding environment are adequate or inadequate in meeting the occupiers’ housing needs (Yeboah-Assiamah, 2015). Along these lines, maintenance priority among occupiers centres on health and safety in use and functionality (Yusofa et al., 2012). Yusofa et al., (2012) further suggest that occupiers’ maintenance creativity is unlikely along aesthetic dimensions. Therefore, occupiers’ efforts in public housing can be valuable as a planning tool (Sharp & Jones, 2012). Involving occupiers in the maintenance of public housing has successfully been practiced in different countries (Yip, 2001; Bengtsson, 2001; Anthony & Lai, 2013).

3.2. Occupiers’ Adaptive Maintenance Initiatives

- Obeng-Odoom & Amedzro (2011) indicates that regulations could provide a mechanism to force landlords to maintain their houses. However, that would require knowledge on profitability of rental housing such that adequate amount of rent is reserved for maintenance from each land lord otherwise too little may be available. A similar analogue can be applied to occupied public housing where occupiers are forced to maintain the housing units by keeping a certain amount of their salaries for that purpose. This approach would however require a complete understanding of maintenance priorities among occupies. Yusofa et al., (2012) reveals that damaged doors and windows are among the top priority for owner occupier maintenance initiatives. Furthermore, for apartments, the number of dwelling units is an important determinant of maintenance condition as it affects the cost of organising maintenance (Yau, 2012). The house types and design can therefore influence the level and effect of occupiers’ maintenance initiatives (Cobbinah, 2010). Apart from house type, the size of the house can also shape occupiers maintenance initiatives. In view of Ibem & Aduwo (2013) respondents in different housing strategies are satisfied with all the dwelling unit features, except those in the Turnkey and PPP houses who were dissatisfied with the size (as measured by number of bedrooms) and design of the building. Furthermore, Yau (2012) notes that living in larger housing units has no significantly higher maintenance priority from among owner occupiers when compared to smaller houses. These observations suggest that occupiers’ initiatives can be linked to house types and size. Generally, occupiers are unlikely to adapt maintenance approaches that are geared towards the sustainability of the housing unit rather those which enhances the current habitability the building.

3.3. Maintenance Neglect among Occupiers

- Occupier’s decision to maintain occupied public houses can be looked at in terms of motivations and constraints (Yau, 2012). This might, in turn, suggest that motivation for undertaking maintenance is linked to utility maximisation hypothesis. Stewart (2003) claims that owner-occupiers may neglect maintenance issues to avoid the stress involved. Maintenance neglect may also ensue from lack of knowledge to identify the basic defects in building elements (Yusofa et al., 2012). Thus, occupiers’ knowledge on defect may affect maintenance strategy especially as far as reporting is concerned (Obeng-Odoom & Amedzro, 2011). This is supported by Abd-Wahab et al., (2015) that knowledgeable people are likely to manage their properties well than unknowledgeable one. This is because occupiers may fail to maintain occupied houses because of the inability to find suitable builder to carry out small-scale maintenance/repair at viable cost (Stewart, 2003). Factors such as salaries of staff and their education level could also shape maintenance initiatives where maintenance neglect is more likely among low income and lower levels of education (Kasim et al., 2015; Stewart, 2003). Cobbinah (2010) indicates that occupiers’ ability towards maintenance and repair initiatives highly depends on salaries though house type moderates that effect by making bungalows and apartment occupiers’ live in poor housing even though their incomes are higher.In addition to the above causes of maintenance neglect, the size of the family unit and duration of occupancy have a significant relationship with public housing satisfaction (Ariff et al., 2011). This suggests that the size of the family for each household determines the expected duration of stay, hence may trigger decision for or against maintanance of public housing. The age of the occupier may also motivate the household maintenance behaviours (Olanrewaju & Abdul-Aziz, 2015; Ariff et al., 2011). Older people are less satisfied than younger ones with public housing suggesting that maintenance neglect could be more likely among those who are highly disatisfied. With regard to marital status, the married couples are more satisfied with public housing than singles; hence the married have limited incentives to neglect the maintenance of their occupied houses. Moreover, the probability of maintenance of a house by the occupier is most likely among older residents, longer stays, skilled manual workers, higher income and owners of new dwellings (Stewart, 2003). Generally, neglect of maintenance is more linked to personnal characteristics of the occupier than the actual condition of the building.

4. Public Housing Maintenance Practices in Tanzania

- During the last two decades, Tanzania overhauled its legal and policy framework in relation to land and housing that was conferred onto her by her former colonial governments (Komu, 2011). This change has brought about several emerging issues like the increasing dominance of the private sector role in housing provision, new roles for public housing agency and privatization of existing public housing. Nevertheless, the government has remained one of the major funder of housing projects through a number of its institutions. These include, for example, the Parastatal Pension Fund (PPF), the Local Authorities Pension Fund (LAPF), the National Social Security Fund (NSSF), the Government Employees Pension Fund (GEPF), the Public Sector Pension Fund (PSPF), the National Insurance Corporations (NIC) the National Housing Corporation (NHC) and the Tanzania Building Agency (TBA). These are well known public corporations that invest directly in housing projects but there are many more public institutions which develop housing facilities for their own uses although in practice, they also rent houses to the public (Mwita & Yan, 2011).According to the Draft Housing Policy, the provision of public housing in Tanzania is the responsibility of the Tanzania Building Agency (TBA). Komu (2011) has pointed out that public housing in Tanzania is influenced by employment policy changes. In his opinion, maintenance problems in public housing can be solved by public housing authorities through exploiting all opportunities and in particular the social capital embedded in their tenants. This can be effectively done by using participation approaches which have been widely used in most land development projects particularly in housing maintenance management (Nnkya, 2008). The existing literature and research reports on public housing in Tanzania has somehow addressed issues pertaining to public housing systems such as maintenance management, maintenance technology, housing policy, maintenance culture and housing provision (Lupala, 2002; Cadstedt, 2004; Harrison, 2004; Kironde, 2006; Mkilania, 2016). The existing state of knowledge further suggests that maintenance of public housing in Tanzania has suffered from lack of funds for a considerable time.

5. Methodology and Data

5.1. Introduction

- The data used in this study were collected using questionnaires which were administered to occupiers of public housing in two universities in Tanzania. The first university is called Ardhi University (ARU). This is a Public University formed after the transformation of the then University College of Lands and Architectural Studies (UCLAS), which was a Constituent College of the University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM). It is located approximately ten kilometers from Dar es Salaam city centers, covering about 10.3Km2. The Ardhi University has about 469 members of staff (by 2015) out of which only 56 members are accommodated in the university’s housing units (ARU, 2015). Most units of the houses are allocated to eligible staff members of the University. The houses vary in size from one bedroom house to four bedrooms. The Staff houses are repaired and maintained under the ARU Estate Management Department. Most of the ARU buildings and infrastructure were constructed in early 1960’s, mid 1970’s and early 1980’s with exception of eight (8) buildings which were constructed in mid 1990’s or in the recent years. It has also been evident that most of ARU buildings and infrastructure have been in use without or with little maintenance due to financial constraints. On the other hand, the required or reported maintenance works are not timely executed due to lack of stocked maintenance materials. The situation has led to progressive deterioration of the structures and hence the need for rehabilitation to restore their functional and aesthetic values.The second University from which data were collected is the UDSM which is the oldest and biggest public universityin Tanzania. The UDSM has the total number of 580 staff houses. The houses are intended to provide the accommodation services to both the senior staff members such as lecturers to junior servants such as Drivers and Personal Secretaries. The Estate Management Department of UDSM is responsible for carrying out the repair and maintenance. The University has a well established guideline for allocation of Staffs Housing. There are those staffs that are entitled to privileges of house accommodation owing to their occupational status and unique job commitments expected of their offices. These are the Vice Chancellor, Deputy Vice Chancellor, Principles, Deans and Directors of institutes, Full Professors, Deputy Principle, Heads of Academic Departments and Major Administrative Units and Academicians whose contract specify accommodation entitlement.

5.2. Data Collection

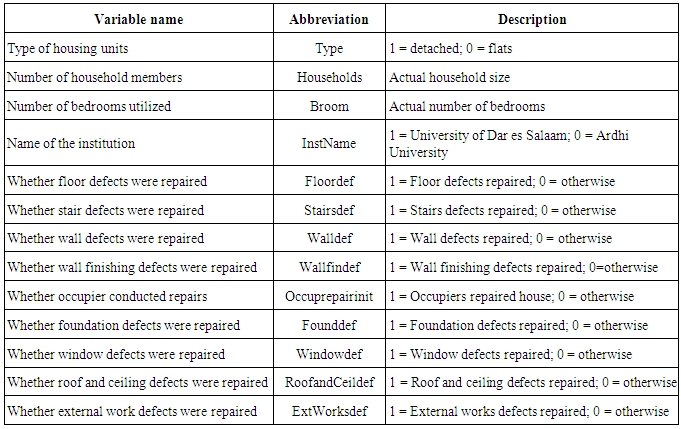

- In order to accomplish the research, the primary data with regard to maintenance of the staff houses were collected from the Estate Managers and staff houses tenants of ARU and UDSM using the Interview guide and the closed ended questionnaires, respectively. The two universities were selected because both are public universities and accommodate some of the oldest public housing units. As public universities, they are non-profit making institutions and housing maintenance is generally through budgetary allocation which is highly challenging and might have attracted a significant amount of occupiers’ initiative in maintenance of occupied houses to improve livability. The interviews involved key informants i.e. Estate Managers from the two universities. In the process of administering the questionnaire to tenants, a clustered sampling design was pre-specified where a target for UDSM was 100 filled questionnaires while for ARU it was 50. Thus, the anticipated sample size was 150 respondents based on the representation of the selected sample respondents from both institutions. The results were 50 respondents from UDSM (50%) and 22 from ARU (44%) yielding to 72 usable questionnaires. The questionnaire was designed to capture housing condition in two period; at occupation and at the time of survey for both structure and facilities elements. The questionnaire also collected personal attributes of the respondents as these could also shape repair initiatives. These personal attributes include; job status or title of the applicant, the size of family and types of the house. Table 1 provides a description of the major variables included in the questionnaire.

|

5.3. Data Analysis

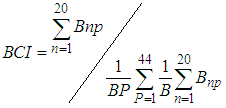

- The data from questionnaires were collected on the individual structural components of buildings and facilities in those building. The collection was based on condition survey attributes by an expert from ARU but by incorporating occupiers’ perception on a 5 ranking scale for each building component. To aggregate the different components an index was created at two different periods in time based on equation 1. The first reflected conditions at the time of occupation and the second is for current (2015) condition. If the two indices differed with the index at occupation being lower than the current one, the house was classified as improved i.e. coded one (1), otherwise it has not improved coded zero (0)1.

| (1) |

= sum of all buildings evaluated,

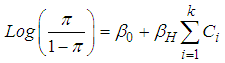

= sum of all buildings evaluated,  = the summation of building components’ ranking relevant to each household.The resulting indices on whether the building conditions has improved or otherwise were used as dependent variables in logistic regression models. The technique was used to compute three models for structural condition improvement, facilities condition improvement and the building condition improvement. The function form of the model can be written as:

= the summation of building components’ ranking relevant to each household.The resulting indices on whether the building conditions has improved or otherwise were used as dependent variables in logistic regression models. The technique was used to compute three models for structural condition improvement, facilities condition improvement and the building condition improvement. The function form of the model can be written as: | (2) |

is the probability of improved structure or facilities or building condition for any occupied house; the ratio

is the probability of improved structure or facilities or building condition for any occupied house; the ratio  is referred to as the odd for an event under consideration. It is a common practice to transform odds into their respective natural logarithms yielding the log odd which is often reported by statistical software; the Beta i.e.

is referred to as the odd for an event under consideration. It is a common practice to transform odds into their respective natural logarithms yielding the log odd which is often reported by statistical software; the Beta i.e.  are the parameters of the model to be estimated using the data while

are the parameters of the model to be estimated using the data while  reflect the intercept;

reflect the intercept;  are the specific determinants of building condition (structural or facilities) improvement which include occupiers characteristics, and initiatives as summarized in Table 1. Solving for the probability

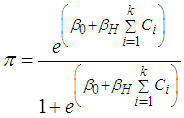

are the specific determinants of building condition (structural or facilities) improvement which include occupiers characteristics, and initiatives as summarized in Table 1. Solving for the probability  the model can be expressed as;

the model can be expressed as; | (3) |

that a particular characteristic i.e. occupiers’ initiative, is not correlated with the probability of housing condition improvement, that is;

that a particular characteristic i.e. occupiers’ initiative, is not correlated with the probability of housing condition improvement, that is; against the alternative

against the alternative  that occupiers initiatives have a significant correlation with house building condition improvement, that is;

that occupiers initiatives have a significant correlation with house building condition improvement, that is; The significance of a single coefficient is then computed as a Z statistic as indicated in equation 4;

The significance of a single coefficient is then computed as a Z statistic as indicated in equation 4; | (4) |

is the estimated

is the estimated  and

and  is standard error of the estimate. This statistic has approximately a standard normal distribution in large samples. The Wald statistic is the square of the ratio of the coefficient to its standard error i.e.

is standard error of the estimate. This statistic has approximately a standard normal distribution in large samples. The Wald statistic is the square of the ratio of the coefficient to its standard error i.e.  . The Wald test is therefore used to construct a confidence interval for

. The Wald test is therefore used to construct a confidence interval for  . Thus one can assert with 100 (1 -

. Thus one can assert with 100 (1 -  ) percent confidence that the true parameter lies in the interval with boundaries shown in equation 5.

) percent confidence that the true parameter lies in the interval with boundaries shown in equation 5. | (5) |

is the normal critical value for a two-sided test of size

is the normal critical value for a two-sided test of size  significance level.

significance level.6. Results of Analysis and Discussion

- The main focus of this study was to examine whether occupiers initiatives leads to significant improvement of the occupied property (structure and facilities) given the different maintenance initiatives undertaken. The next sections presents the major findings obtained from the study in regard to the research problem. The first section provides the results of a binary logistic model which was implemented to predict the probability that structural conditions of occupied public housing is likely to have improved during the time of occupation by the current occupiers. The second section concentrates on a model on facilities condition improvement and the last part combines both structural and facilities improvement in what is referred in this paper as housing condition improvement.

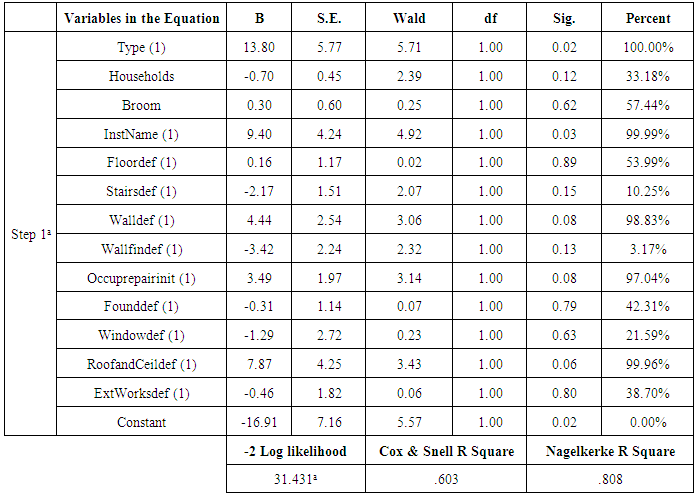

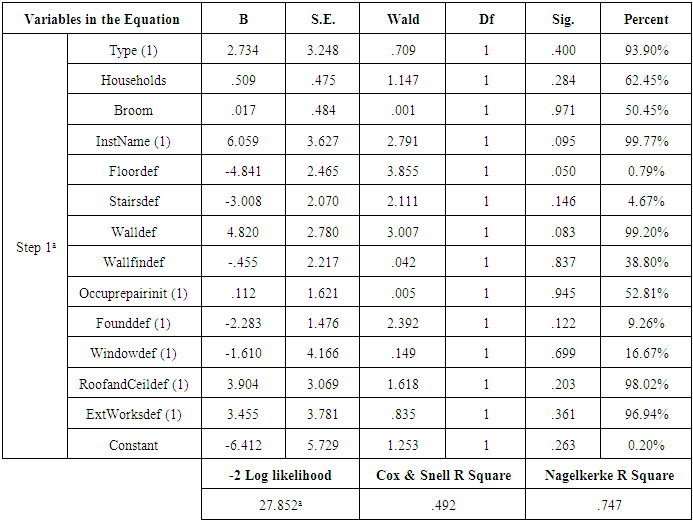

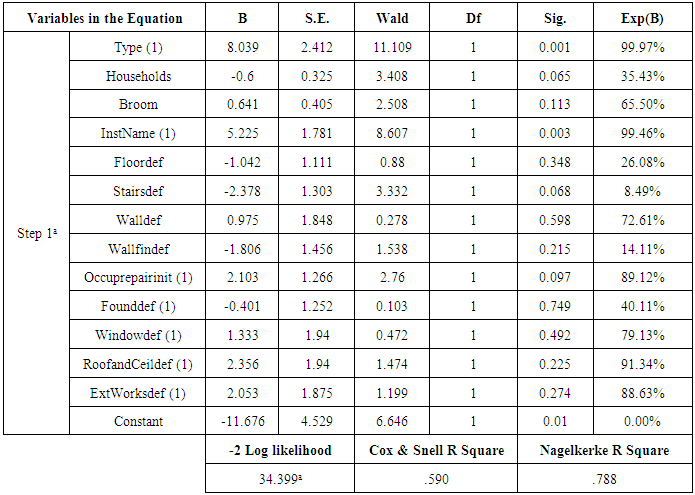

6.1. The Effect of Occupiers Initiatives

- This study has indicated that occupier’s maintenance initiatives are positively correlated with improved house building conditions. With respect to the physical condition of public housing the results presented in Table 2, tenants’ initiative (Occuprepairinit) was the leading factor that significantly impacts structural condition improvement. The structural condition of public housing is 97% likely to be higher if the occupier took certain repair or maintenance initiatives than if he/she did not.In terms of the effect of occupiers repair initiatives on the facilities condition improvement, the results presented in Table 3, suggest a positive but statistically insignificant effect. The facilities condition improvement is 52.8% more likely if the occupier took certain repair or maintenance initiatives than when she/he did not. Thus, occupiers’ initiatives to improve occupied public housing are not significantly associated with building facilities improvement.The results presented in Table 4 indicates that the log odd of building condition improvement is 89% likely if the occupier took certain initiatives to maintain the house than when he/she did not. The nature of occupiers initiatives are evaluated based on descriptive statistics in the following subsections.This result confirms the discussion made earlier on the occupiers’ initiatives towards maintenance of public housing. Thus, occupiers are the primary initiator of maintenance work and together with other actor they influence the amount of maintenance work undertaken (Yusofa et al., 2012; Matindi, 2013). Owner-occupier can be involved into the management of public housing through sharing of information and ideas (Lau, 2002). However, Yusofa et al., (2012) had different opinions, arguing that maintenance is a complex process to be handled by occupiers. Stewart (2003) observes that occupiers would prefer to undertake improvement rather than repair though this was not evident in this study. The major drawback in public housing provision in many public institutions has been increasing, especially targeting supply rather than maintenance of the existing building structures. The observation made in this study suggests that occupier’s initiative in doing maintenance in a public housing contributes significantly towards improved building condition.

|

|

|

6.2. The Nature of Occupiers Maintenance Initiatives

- A further analysis was carried out to examine the nature of occupiers’ maintenance initiatives in order to draw a firm conclusion in line with the preceding observation. For that purpose the conceptual relationships in Figure were scrutinised in terms of the collected data. The results are presented hereafter.

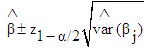

6.2.1. Adaptive Maintenance

- Occupier’s efforts to repair public houses may be determined by the extent and severity of the associated defects to which maintenance is sought. This is reflected in the impacts of defects as impacted on the occupier and willingness to pay for the repair of the defects. The results in Figure 2 suggest that occupiers would exert more effort when the causes of defects are well known i.e. originate from a single source. Approximately 22.22% of occupiers exerted maintenance efforts through own initiatives that were above the median effort in the sample while 15.28 percent of the respondents had exerted maintenance efforts below the sample median effort. However, when there are multiple causes to defects, occupier’s efforts tend to be relatively low. Those exerting high efforts are 19.44% while those exerting low efforts are 23.61%. The low difference between the two groups of occupiers suggests that occupiers’ maintenance initiatives are relatively high in single cause defect than in multiple sources defects. The complexity of maintenance problems therefore determine the extent to which occupiers initiatives may be carried out.Generally, many of the existing methods of repair are associated with not only high implementation costs but also bureaucracy and favoritism. Those in maintenance management hierarchies may complicate even a minor repair problem to an extent of exacerbating it due to delay. Occupiers’ initiatives can be highly adaptive if high repair efforts are associated with relatively low cost. The data presented in Figure 2(b) indicate that 52.50% of occupiers who exerted high effort on repair faced low cost while 25% exerted low efforts. The situation reverses when occupiers fall in the high repair cost side. About 3.33% exerted high repair efforts while 4.17% exerted low repair efforts. These observations suggest that repair cost deters to a certain extent, occupiers effort to repair their occupied public houses, thus signaling adaptive occupiers efforts in public housing maintenance.

| Figure 2. Occupiers repair effort in relation to causes of defects and repair cost |

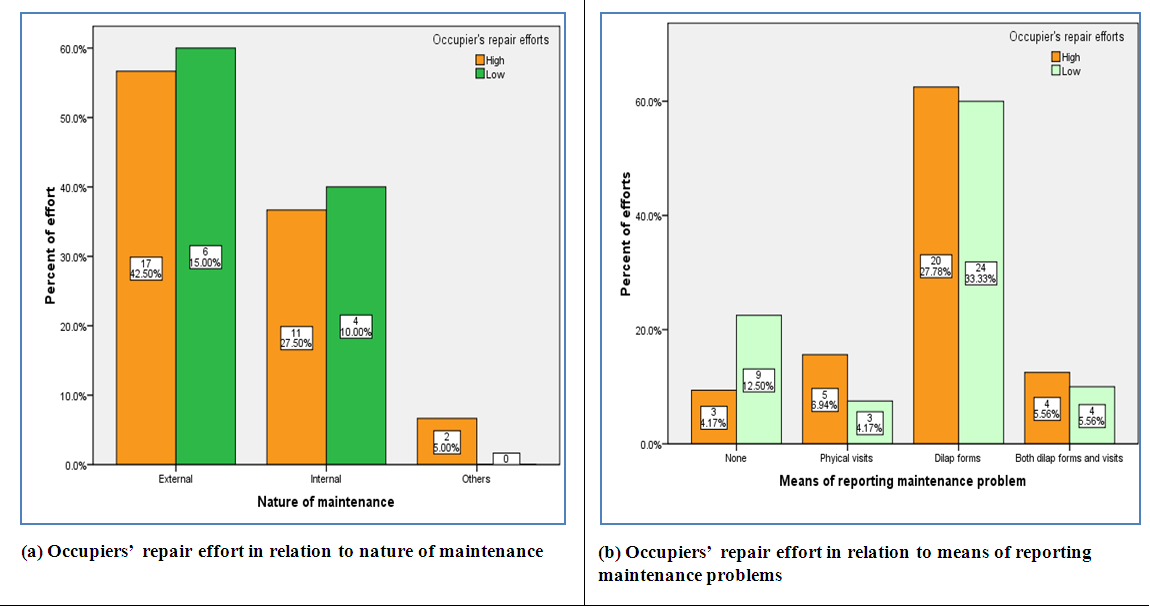

6.2.2. Creative Maintenance

- Creative maintenance as implemented by occupiers is reflected in activities other than internal and external construction works. These activities mainly involve creation of additional space to support larger family size or some informal activities such as animal rearing within the area of public housing. Based on the responses in this study, these creative activities account only for 5% of maintenance efforts, suggesting that occupiers initiatives are less likely to be creative rather accommodating in order to support livability of the house. Figure 3 (a) indicates that 42.5% of the occupiers exerted high maintenance efforts in external works while 15% exerted low effort in similar areas; 27.5% exerted high efforts in maintenance of internal works and 10% exerted low efforts. The study did not observe any creative mechanism to report dilapidation of occupied housing units other than the traditional ones. In reporting maintenance, the common approach is filling out dilapidation forms where 27.7% of occupiers who use dilapidation forms to report maintenance problems also exerted high effort in their own initiatives and 33.33% exerted low efforts. Nearly 12% of those who did not report maintenance problem also exerted low own initiatives towards maintenance compared to 4.17% of those who do not report but exert high efforts in maintenance. Generally, reporting maintenance go hand in hand with more occupiers’ effort towards maintenance of public housing.

| Figure 3. Occupiers repair efforts in relation to nature of defects and means of reporting |

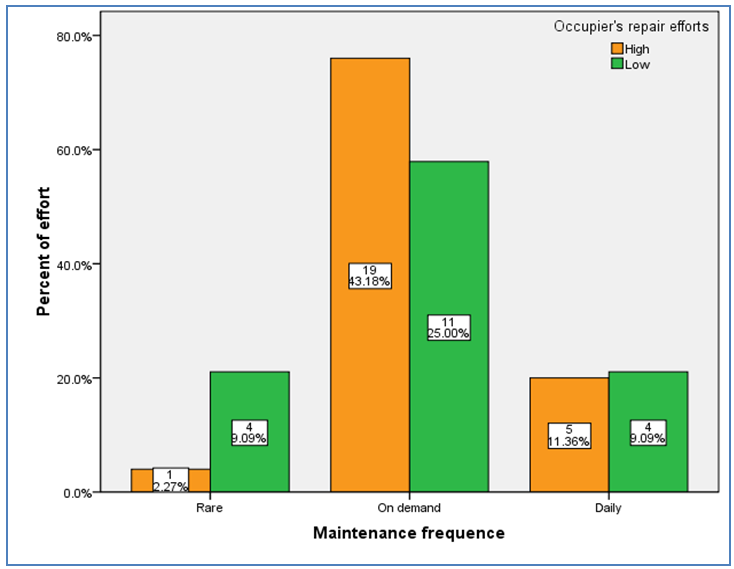

6.2.3. Neglect of Maintenance in Public Housing

- Neglect of public housing may not only emanate from the management but also from the occupiers if it is possible to conduct maintenance through occupiers’ initiatives. The observations in this study suggest that when maintenance is rarely conducted occupiers initiatives tend to be almost nonexistent. Figure 4 (a) suggests that high maintenance efforts under rare maintenance frequency is only 2.27% among the surveyed occupiers. When maintenance frequency is on demand, 43.18% of occupiers would exert high effort compared to 25% who exerts low efforts. This larger margin suggests that occupier’s maintenance efforts are principally a response to public housing conditions. The highly dilapidated houses call for more occupiers efforts while more recent houses may call for a limited attention among occupiers. These observations provide evidence that neglect of public housing maintenance is less likely to emanate from occupiers rather other sources of neglect need to be explored. Potentially, neglect is likely from the maintenance management team as long as the composition of the team is of people not among occupiers of public houses.

| Figure 4. Occupiers’ repair effort in relation to nature of maintenance |

| Figure 5. Occupiers’ repair effort in relation to nature of maintenance |

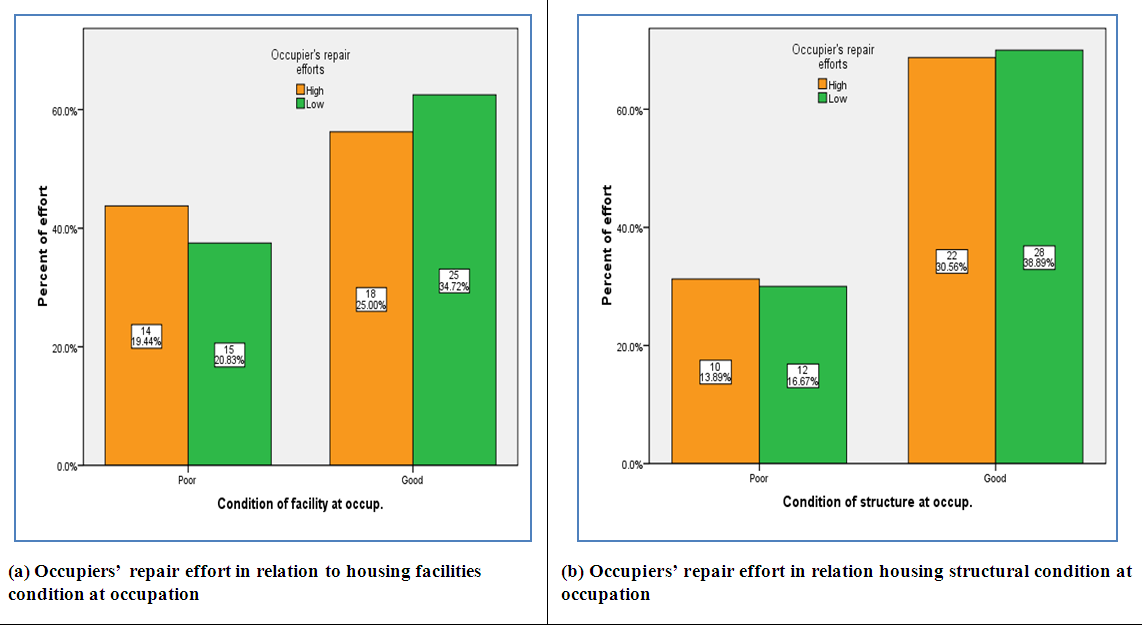

6.3. Other Effects on Building Condition

- The data presented in this study have suggested that a significant positive effect on building improvement emanates from the type of the building, the institution that owns the building and the occupiers’ initiative. The study has also identified two negative and significant effects on public housing condition in the studied universities. These are household size of the occupier and stair defects maintenance initiatives. In terms of house types, the study has observed that detached houses when compared to flats seem to be associated with improved building condition. The results of the logistic regression model for the determinants of facilities condition improvement are presented on Table 3. The facility condition improvement is higher by 93.9% when the house type is flat than when it is a detached house type though the effect is not statistically significant. The results suggest further that the facilities condition is 62.45% likely to have improved for each additional member in the family and 50.45% for each additional bedroom. The two relationships are however not statistically significant. The structural condition is almost 100% likely to have improved in flat than in detached housing type and this relationship is statistically significant. These findings support earlier assertions by Jiboye, (2013) and Ibem & Aduwo (2013) who indicate that house types shape quality perception among occupiers and hence could be an important determinant of occupiers’ maintenance initiatives. Flats which are only available at the UDSM seem to not only have been neglected but also suffer from old age which goes hand in hand with deterioration. The findings have confirmed the study by Cobbinah (2010) who observes that maintenance problems are often associated with the age of the building. Some UDSM flats are also found in estates with little external sources of repair or even attention. Thus, occupiers have little contacts with neighbours regarding facilities alterations or maintenance issues. Considering house type, previous studies by Cobbinah (2010) and Yau (2012) had shown that single unit houses suffer severe maintenance problem than bungalows which tend to be attributed to the larger number of occupants per house than in bungalow where the occupants are few, aptly described by the sage: “Nobody disturbs you, but on the other hand nobody helps you as well”. Occupiers are fully responsible for doing everything; this might be the reasons why facilities condition in detached houses seems to be better than in flats.The study has further observed a significant owner effect on structural condition improvement for public housing as shown in Table 2. The building structural condition is almost 100% likely to have improved if owned (InstName) by UDSM than if owned by ARU. At the institutional level, UDSM has improved house building condition than ARU, thus complementing similar observations in Cobbinah (2010) who observes that government institutions differ in terms of maintenance levels of their respective housing units. This could be attributed to the fact that UDSM is a very big and old institution both physically and financially compared to ARU. The findings confirmed the study by Lau (2002) which suggests that the success of any occupiers’ participation depends on the institutional policy.Apart from positive determinants of house building condition improvement, this study has also observed two factors which are associated with unimproved house building condition. The first one is family size of the occupier. The results in Table 4 suggest that there is a negative relationship between the occupiers’ family size and structural condition of public housing under consideration though this relationship is not statistically significant. This observation might be linked to the fact that household with large families tend to concentrate much on the provision of important items related to the family, like the provision of education, food and other necessities to family than maintenance. Given these household level responsibilities, it is unlikely that those maintaining bigger families may devote resources towards maintenance. This finding is firmly supported by Ibem & Aduwo (2013) which established that low-income households are less likely to be satisfied with their occupied houses due to poor condition. Similarly, Boamah (2014) advanced that household size has an impact on shared facilities condition.In a similar vein, stairs defect maintenance, though seemingly a minor maintenance initiative, seems to be carried out only under serious condition of disrepair. Stairs are common in flats and given their old age and probably serious neglect, occupiers’ initiative might have targeted these stairs to maintain liveability otherwise upper floor apartments may not be reachable. Table 4 suggests that improvement of the building condition is only 8.5% likely if stairs are maintained than when they are not. Again, structural condition and stability of the overall building may marginally respond to stair defect maintenance in detached houses. This finding supports earlier assertions by Ammar et al., (2012) which observed that stair is one of the problems evidently seen in public building especially in a shared flat, though in this study such effect is only statistically significant at 90 percent confidence interval.All other variables investigated in this study were found to be limitedly associated with house building condition. However, it is important to provide a snapshot discussion on these variables in orders to instil some motivation for further research. The study has observed that bigger houses are likely to have improved condition than smaller one. The earlier observations by Ibem & Aduwo (2013), Ishiyaku et al. (2014) and Ishiyaku et al. (2016) on the size of the house, supports this findings that, size of the house has a significant correlation with the overall public housing condition. Potentially, this could be attributed to the possibility that bigger houses are often occupied by bosses who apart from higher personal financial resources, they can command institutional resources in favour of their houses. The administrative hierarchies in many developing countries tend to favour those in managerial position than those in technical position. However, this is inconsistent with the view of Yau (2012) who noted that living in larger housing units has no significantly higher maintenance priority from among owner occupiers when compared to smaller houses.The study has also noted a positive building condition improvement based on efforts geared towards wall, windows, roof and ceiling and external works repairs. Occupiers may maintain such components even when maintenance is neglected by the responsible authority. External work defects like pavement, drainage channels, pipe and fittings are likely to be associated with building condition improvement. Table 3 suggests that window and floor defects where the facilities condition improvement is 16.67% and 0.79% less likely if the window and floor repairs respectively are carried out than if they are not. The facilities condition is higher by almost 100% if wall defects are repaired than when they are not. Wall defects are common in public housing due to poor workmanship (Cobbinah, 2010). Similarly, structural condition is higher by 98.2% if the roof and ceiling defects are maintained than when they are not. Moreover, the condition of facilities is 96.9% more likely to have improved when external works repairs are carried out than when they are not. The three effects are however, not statistically significant except for the effect of wall defect repairs. The findings of the present research concur with those of studies by Ishiyaku et al., (2014) and Kasim et al., (2016). These just cited studies found that the quality of ceilling, windows roof, wall and external works has a significant correlation with the overall building condition. Defects in the external works usually lead to failure requiring repair or servicing. It is therefore, necessary only to have a planned schedule for foreseeable servicing and replacement of these components. However, avoiding exhausting the designed lifespan of the external work can prevent sudden breakdown of services that causes undesirable or even disastrous consequences.A part from the positive non-significant determinants of building condition improvement, three defect repairs were found to be negatively associated with building improvement, though not significantly. The wall finishing defects are less likely to be associated with building condition improvement. This view is supported by Ishiyaku et al., (2016) who claims that condition of wall finishing is weakly linked to the performance of building. This can be attributed to the fact that wall finishing defects cannot be significantly associated with both facilities and structural condition improvement. These are non-structural defects (usually in plaster or other finishes with cement sand rendering as base). Therefore, a cosmetic shrinkage cracks in plaster or other forms of wall finishes will affect the appearance only and do not pose any safety concern. This could help explaining why this defect is negatively associated with building condition improvement. A similar observation was made with respect to stair and foundation defects. A number of reasons could justify this lack of association between maintenance efforts on these defects and building condition improvement and may include:Ÿ Some of them have a relatively shorter life span than the building structure except for foundation defects;Ÿ These defects usually lead to failures which require only repair or servicing. It is therefore necessary only to have a planned schedule for foreseeable servicing and replacement for components;Ÿ Most of failures with regard to these defects require only regular servicing and maintenance or replacement to prevent failure.

7. Conclusions

- The findings of the present research have proven that occupiers’ maintenance initiative significantly improves building. An occupier undertaking maintenance initiatives has 89 percent chance of improving the overall building condition above average condition than if she/he did not. Moreover, the results highlighted the structural condition of occupied public housing is likely to improve in flats than in detached houses and the building structural condition is almost 100% likely to have improved if owned by UDSM than if owned by ARU. Also, the structural condition is almost 100% likely to have improved in flat than in detached housing type and this relationship is statistically significant. While, bigger houses i.e. those with more number of bedrooms are more likely to be improved than smaller ones though the relationship is not statistically significant. These occupiers’ initiatives are however, biased in favour of accommodative rather than adaptive maintenance and there is limited creativity in occupier’s maintenance strategies. In general, most of the buildings in the two universities might have exhausted lifespan. Attesting to that, a great deal of their facilities were noted heralding overt signs of dilapidation and decay. Tragically, though, it was highly uncertain if there were concerted efforts to remedy the situation, especially by incurring the costs of demolishing or re-constructing the buildings. Therefore, it is vital for the government to acknowledge and appreciate the significant influence of occupiers’ initiative by incorporating them in maintenance of public housing. A monetary reward could be the most appropriate means to encourage owner initiatives towards maintenance of public housing though other forms of compensation may be sought as well. In terms of advancing knowledge and scholarship, the current study recommends for further studies on the effect of minor repairs on the structural facilities of public house condition. The proposed study has to focus specifically on the reduced stability of the whole structure which may not be observable in a one-time condition survey like the one conducted in this study.

Note

- 1. The index of structural condition was created based on the 5 scores likert scale on the condition of the following building elements; foundation, wall, window, door, external works, ceiling, floor, stairs, roofs, finishes and Facilities condition was assesses based on the following facilities; kitchen, toilet, bathroom, electricity, water services, electric fan, air conditioning and drainage system.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML