Oluwole Joseph Oni1, Gerrit Crafford2

1Department of Quantity Surveying, Federal Polytechnic, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria

2Department of Quantity Surveying, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa

Correspondence to: Oluwole Joseph Oni, Department of Quantity Surveying, Federal Polytechnic, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Construction operatives have been reportedly scarce to source within the Nigerian construction industry in the recent times. This has been attributed inter alia to a number of factors including the training system. Within the Nigerian context there are two models of training construction site operatives, namely the formal and the informal models. The aim of this study is to evaluate the formal training model with the view to developing strategies for improving the system in Nigeria. The study employs questionnaire survey, a quantitative methodology for gathering appropriate data. It surveys the opinions of trainers from the formal training system with regards to government policy, funding, recruitment, staffing, training approaches and facilities. The study develops strategies for mitigating the challenges of inadequate supply of operatives for the Nigerian construction sector.

Keywords:

Construction, operatives, Formal Training, Shortages, Nigeria, Approaches

Cite this paper: Oluwole Joseph Oni, Gerrit Crafford, Performance Evaluation of the Formal Training System of Construction Operatives in Nigeria, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 6 No. 3, 2017, pp. 87-93. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20170603.03.

1. Introduction

The persistent shortage of site operatives in Nigerian construction industry has been reported to be one of the major factors responsible for housing and infrastructure deficit in the country (Agbola and Olaoye, 2008). Nigeria has the largest population among the black African countries and a very high growth rate which was estimated at 3.2% by the Nigeria National Population Commission (NPC 2006). This has engendered acute housing and infrastructure gaps in country. Skilled site workers are essential to efficient housing and infrastructure delivery (Fatimilehin, 2010). Nworah (2008) asserts that there is an influx of construction site workers from neighbouring West African nations such as Benin Republic and Togo to Nigeria; they came to fill the gaps created by the inadequate supply of artisans. The objective of this study is to appraise the performance of the formal training model of construction operatives through the gathering and analysis of relevant data that would facilitate the articulation of appropriate strategies for improving the system.Models of Training Construction Site Workers Available evidence reveals the consensus of authors that there are three basic models of artisan training which include the formal (school-based) model, the dual model and the informal model (Carrero, 2006:157-160; DFID, 2007; Kogan, 2008:43; CEDEFOP, 2008a; World Bank, 2012; Werner, Núria, Ricarda, and Klaus, 2012:2-7; ILO, 2012; Carroll, 2013:56). These may be modified as one moves from one region of the world to the other. This study focuses only on the evaluation of the formal model in the study area. The formal training modelWerner et al. (2012:2-7) describe the school-based model of artisan training as a schooling system that provides youth with practice-oriented knowledge and skills required in specific occupations and learning. According to the European Centre for Development of Vocational Training, (CEDEFOP, 2008a) the aim of general education is to provide youths with general, often academically oriented knowledge as the foundation for further education and training. While school-based vocational education follows a formal curriculum that combines general and occupation-specific knowledge to equip youths with occupational oriented knowledge and skills for the world of work. Variations in the types of school-based model may arise with respect to the academic level of vocational schooling (World Bank, 2005). Essentially, skills acquired under this model are mostly general and transferable between employers. The school-based vocational training affords youth the opportunity to acquire the skills that are needed to earn a living and to be relevant within the economy. Especially for those who do not have the ability to continue with the higher education track (Werner et al., 2012:2-7). However, critics have argued (Kogan, 2008:43; Carrero, 2006:157-160) that the vocational schooling pathway is poorly perceived by the public. It is considered to be a dead-end for academically aspiring youth; given the low percentage of youths who practically manage to further their education after vocational schooling due to discrimination of vocational qualifications within the general education circles.Strengths of the formal modelAvailable evidence (Carrero, 2006:157; CEDEFOP, 2010) indicates some of the strengths of the school-based training system which include:• Unified curricula: In the informal model, the training content is determined by the individual trainers. However, under the school-based model, the curriculum of training is moderated by the appropriate government regulatory organ and the same standards are benchmarked and sustained in all the different training institutions.• Transferable skills: Skills acquired from the school-based model are generally transferable between employers due to the standardised curricula of training and the regulated certification examination conducted at the end of the training period (UNESCO, 2010; CEDEFOP, 2008a).Weaknesses of the formal model The drawbacks identified with the school-based model include skills mismatch; reduced parental influence and limited learning prospects.• Skills mismatch: According to DFID (2007) and, Tattara and Valentini (2009:197-212) the school-based model is characterised by a weak linkage between the skills required in the labour market and the training provided by the training institutions. This is due to the absence of employers’ inputs in the training design and delivery. Consequently, skills mismatch and obsolescence characterise the graduates from the system; making it difficult for young vocational graduates to enter the labour market (Roger and Zamora, 2011:380-396).• Reduced parental influence: Werner et al., (2012:2-7) argue that the adoption of a vocational education track at the basic school level which is the practice in some European countries has the capacity of reducing parental influence on the background and educational choices of the young people in society. This is so because the young ones have to make career choices too early in life when they are yet to be sufficiently informed and guided by their parents on career issues.• Limited learning prospects: Opportunities for further education are often limited for those who have chosen the vocational track at the basic school level. In cases where this is possible, it usually necessitates a higher cost for crossing to the general education track for the purpose of lifelong learning and further career opportunities (Carrero, 2006:32).

2. Methodology

Questionnaire survey, a quantitative methodology was adopted for the study for the following reasons: It helps to save time spent on the study since a lot of data can be obtained within a short period of time; It is relatively cost-effective; It does not require a lot of attention and time from the respondents, as they only need to tick on the answers, The data capture is made simple for the purpose of analysis by using a computer software program (Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2009:35; Struwig and Stead, 2010:4). For the purpose of this study, opinions of members of staff and management from 13 vocational training colleges from South Western Nigeria were canvassed. The questionnaires were administered to the respondents by hand. This was adopted by the researcher in order to obtain a reasonable response rate that would help realise the aim of the study. The use of electronic questionnaire was difficult given the low penetration of the internet in the study area.

3. Analysis of Results

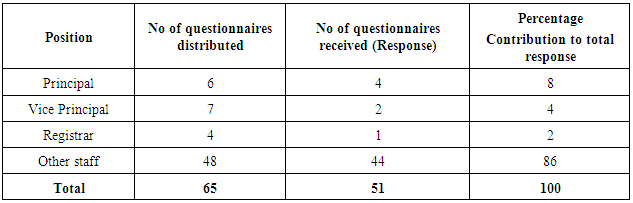

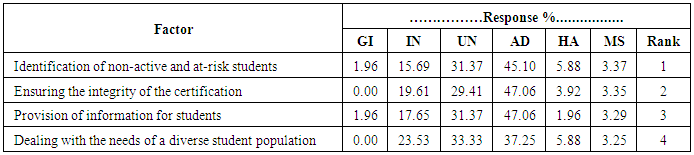

The following sections present the analyses of data from training college management and staff members on the formal system of training site operatives. The analysis covers strategic areas of the training operation. The areas covered included recruitment and admission strategy; staffing; teaching and learning strategy; student assessment policy and procedures; physical infrastructure; training facilities and library resources; regulatory mechanism; government policy and level of funding; administrative services; and proposed strategies for improving training in the colleges.Table 1 indicates that the highest proportion of respondents came from other staff members. This can be explained by the relatively high population of the other staff members as compared with the management staff. Other factors were the availability and the willingness of the other members of staff to participate in the study. Table 1. Vocational college management and staff

|

| |

|

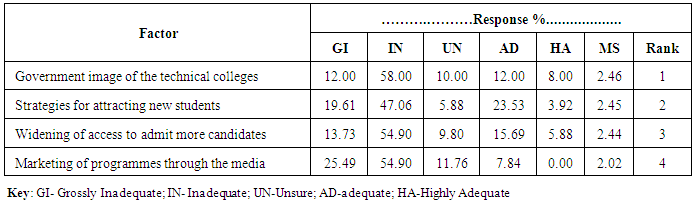

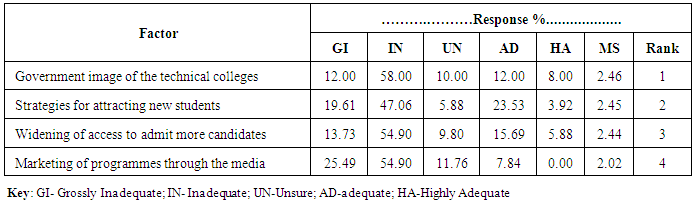

The respondents were asked to rate the option that best describes the level of adequacy of the following factors that impact on VT colleges. Table 2 indicates the respondents’ perceptions on the adequacy of the factors relating to recruitment and admission strategy impacting on training in the VT colleges. In general, it can be observed that the respondents perceived the identified factors in Table 2 as being inadequate with all the MS > 1.80 ≤ 2.60. Notable among the factors is marketing of programmes though the media, which ranked 4th and the least among the factors with the MS values of 2.02.Table 2. Recruitment and admission strategy

|

| |

|

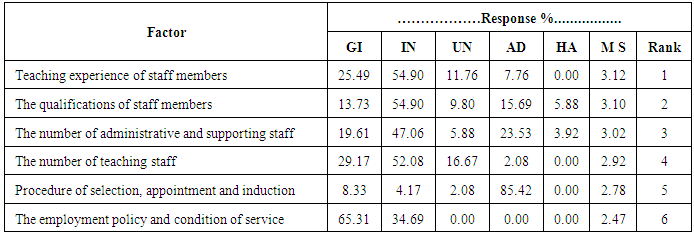

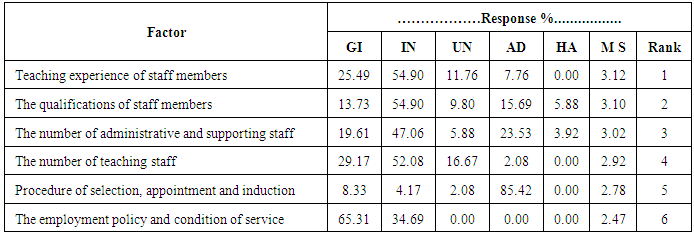

From this result, the respondents can be deemed to perceive the lack of marketing of programmes through the media as the recruitment / admission related factor that negatively impacts most on artisan training in the colleges. Other factors such as the widening of access to admit more candidates; strategies for attracting new students; and government image of the technical colleges are also perceived as inadequate and negatively impact on the training of artisans in the VT colleges. Table 3 indicates the respondents’ perceptions on the adequacy of factors relating to staffing impacting on the training of artisans in the VT colleges. It can be observed that the respondents perceived employment policy and conditions of service as being inadequate with the MS > 1.80 ≤ 2.60 and ranked lowest (6th). All the other factors have MS > 2.60 ≤ 3.40 which indicates that the respondents are unsure about the adequacy of these factors.Table 3. Staffing in the VT colleges

|

| |

|

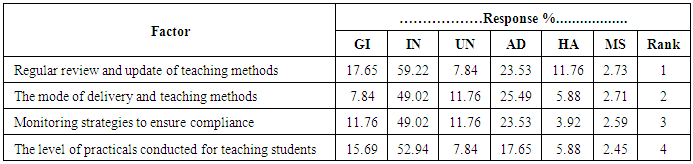

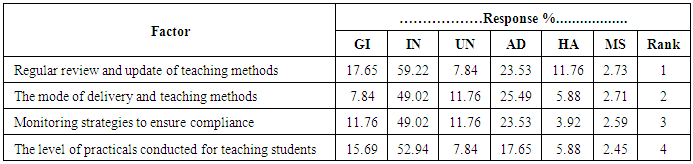

From this result, the respondents can be deemed to perceive the employment policy and conditions of service as the factors that negatively impacts on the artisan training the most in the colleges. However, the respondent can be deemed to be unsure about the adequacy of teaching experience of staff members; qualifications of staff members; number of administrative, teaching and support staff members and procedures of staff selection, appointment and induction in the VT colleges.Table 4 indicates the respondents’ perceptions on the adequacy of the factors relating to teaching and learning strategy impacting training in the VT colleges. It can be observed that the respondents perceived the level of practicals conducted for teaching students; and monitoring strategies to ensure compliance as inadequate with MS > 1.80 ≤ 2.60 and were ranked 4th and 3rd among the factors respectively. It can also be observed that the respondents are unsure about the adequacy of the mode of delivery and teaching methods; and regular review and updating of teaching methods with MS > 2.60 ≤ 3.40.Table 4. Teaching and learning strategy

|

| |

|

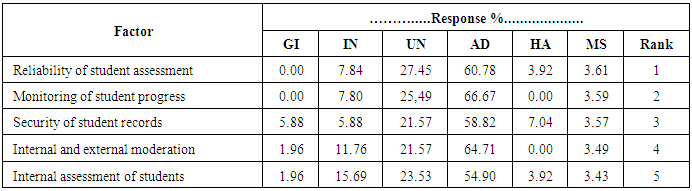

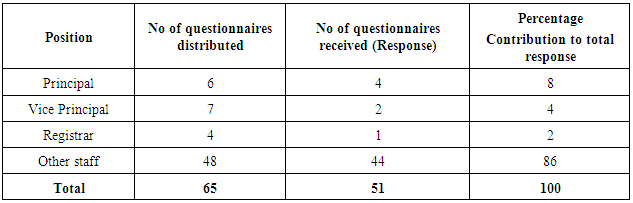

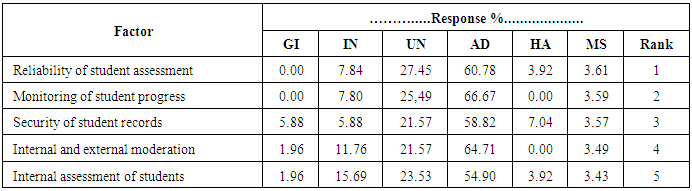

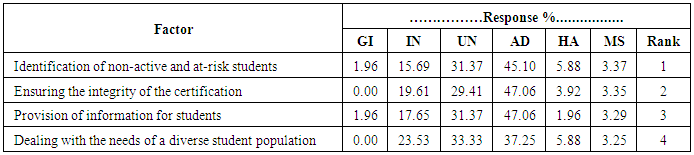

From this result, the respondents can be deemed to perceive the level of practicals conducted for teaching students; and monitoring strategies to ensure compliance as the factors relating to teaching and learning mostly inadequate and negatively impacting on the training in the VT colleges.Table 5 indicates the respondents’ perceptions on the adequacy of the factors relating to student assessment policy and procedures in the VT colleges. It can be observed that the respondents perceived the identified factors relating student assessment policy and procedures in Table 5 as being adequate with all the MS > 3.40 ≤ 4.20.Table 5. Student assessment policy and procedures

|

| |

|

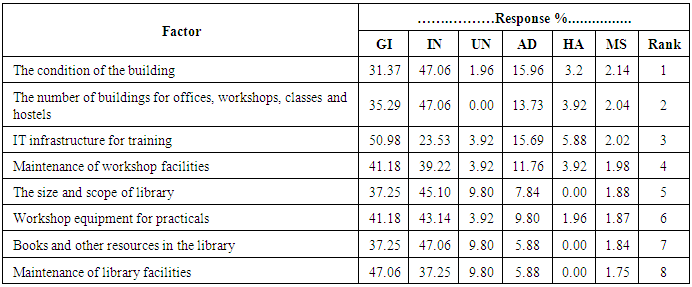

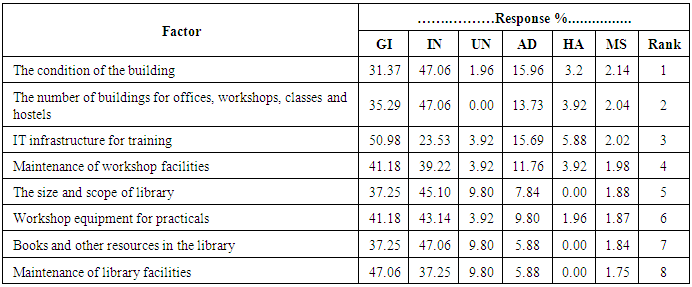

From this result, the respondents can be deemed to perceive reliability of student assessment and monitoring of student progress as the most adequate factors with regards to student assessment policy and procedure in the VT college system. They are ranked 1st and 2nd with MS values of 3.61 and 3.59 respectively among other factors.Table 6 indicates the respondents’ perceptions on the adequacy of the factors relating to physical infrastructure, training facilities and library resources affecting training in the VT colleges. It can be observed that the respondents perceived all the factors as being inadequate / grossly inadequate with all the mean scores falling within MS > 1.00 ≤ 1.80 and MS > 1.80 ≤ 2.60. It is noteworthy that the maintenance of library facilities; books and other resources in the library and workshop equipment for practicals are ranked lowest - 8th, 7th and 6th with MS values of 1.75, 1.84 and 1.87 respectively.Table 6. Physical infrastructure, training facilities and library resources

|

| |

|

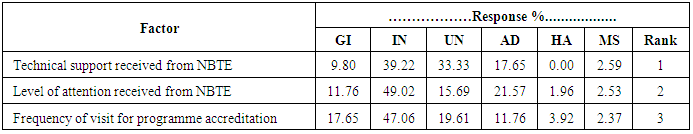

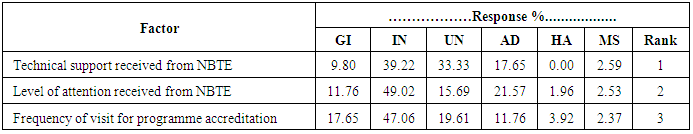

From this result, the respondents can be deemed to perceive, maintenance of library facilities; books and other resources in the library; and workshop equipment for practicals as the factor relating to physical infrastructure, training facilities and library resources as most inadequate factors that negatively impact on the artisan training the in the VT colleges.Table 7 indicates the respondents’ perceptions on the adequacy of the factors relating to the regulatory mechanism impacting on training in the VT colleges. The National Board for Technical Education (NBTE) is the regulatory body for the VT colleges. It can be observed from the table that the respondents rate NBTE operations as being inadequate with all the MS > 1.80 ≤ 2.60. Notable among the factors is the frequency of visits for programme accreditation, which ranked 3rd and the last among the factors assessed with MS value of 2.37.Table 7. Regulatory mechanism: the NBTE as the regulatory body

|

| |

|

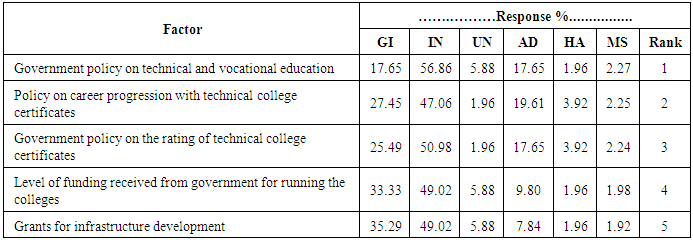

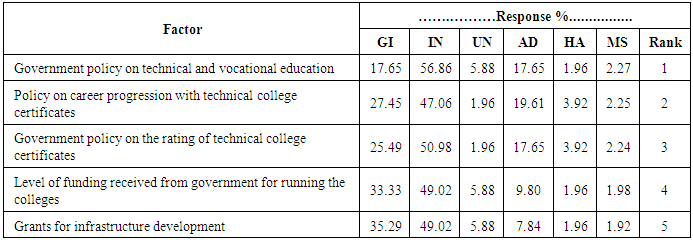

From this result, the respondents can be deemed to perceive the frequency of visits for programme accreditation as the most inadequate factor relating to regulation that most impact on the training of artisans in the VT colleges. The level of attention received from NBTE; and the technical support received from NBTE are also inadequate and negatively impacting on the training in the VT colleges too.Table 8 indicates the respondents’ perceptions on the adequacy of the factors relating to government policy and the funding of training in the VT colleges. In general, it can be observed that the respondents perceived the identified factors in Table 8 as inadequate with all the MS > 1.80 ≤ 2.60. Notable among the factors are grants for infrastructure development; level of funding received from government for running the colleges; and government policy on the rating of VT college certificates which ranked lowest, 5th, 4th and 3rd among the factors with the MS of 1.92, 1.98 and 2.24 respectively.Table 8. Government policy and level of funding

|

| |

|

From this result, the respondents can be deemed to perceive grants for infrastructure development; level of funding received from government for running the colleges; and government policy on the rating of VT college certificates as the most inadequate factors relating to government policy and funding and negatively impacting on the training offered in the VT colleges.Table 9. Administrative services

|

| |

|

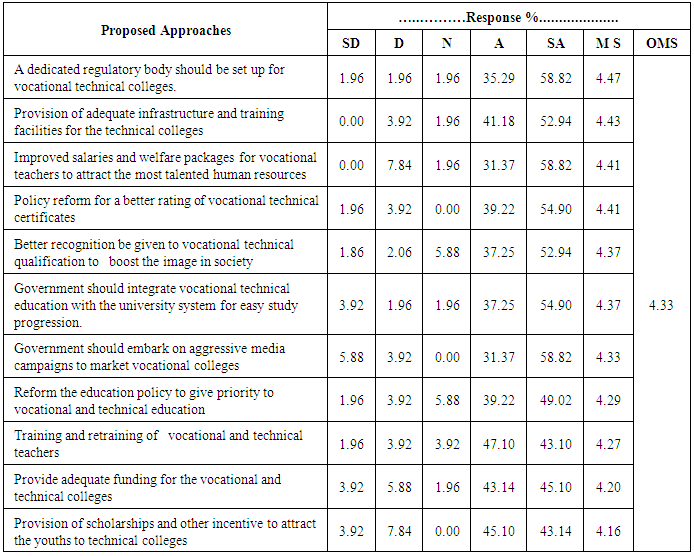

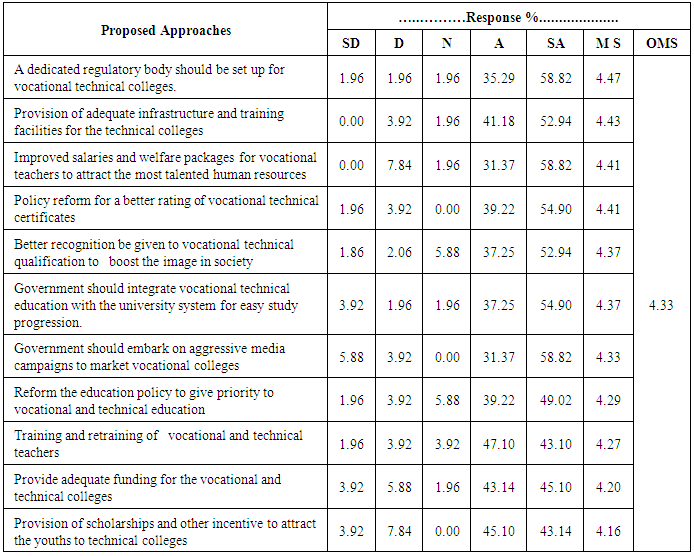

Table 9 indicates the respondents’ perceptions on the adequacy of the factors relating to administrative services in the VT colleges. It can be observed that the respondents are unsure about the adequacy of the identified factors in Table 6.42 with all the MS > 2.60 ≤ 3.40.From this result, the respondents can be deemed to perceive factors relating to administrative services in the VT colleges as neither inadequate nor adequate.Approaches for Repositioning the formal training modelTable 10 indicates the respondents’ perceptions on the proposed approaches for improving the VT college system of training. It is noteworthy that most of the strategies have MS> 4.20 ≤ 5.00 and an overall mean score (OMS) of 4.33 for all the proposed approaches as shown in Table 10 which indicate that the respondents strongly agree with the proposed approaches for improving the VT college system of training artisans. Most notable among the proposed approaches are the ones with the MS values of 4.33 and above, noting here that OMS value is 4.33.Table 10. Approaches for Bridging the Gap in Formal Training System

|

| |

|

From this result the respondents can be deemed to agree with the following proposed approaches of – a dedicated regulatory body should be set up for vocational technical colleges; provision of adequate infrastructure and training facilities for the technical colleges; improved salaries and welfare packages for vocational teachers to attract the most talented human resources; policy reform for a better rating of vocational technical certificates; better recognition be given to vocational technical qualification to boost the image in society; government should integrate vocational technical education with the university system for easy study progression; and government should embark on an aggressive media campaigns to market vocational colleges. These are the most recommended approaches for improving the VT college system for training artisans.

4. Conclusions

The main objective of this study is to appraise the performance of the formal training model of construction operatives through the gathering and analysis of relevant data that would facilitate the articulation of appropriate improvement strategies. It has been empirically established that the formal system of training construction operatives is underperforming; and a number of factors responsible for this have been identified and analysed. The study has also developed improvement approaches for revitalising the formal model of training of construction workmen in order to ensure quantitative and qualitative supply of operatives for infrastructure delivery in the study area. Clearly, there is an urgent need for appropriate actions to be taken so that the situation will not be exacerbated. The approaches advanced in the study, if implemented would reasonably help to plug the gap in supply and assist to provide adequate operatives for the future need of the construction sector and thus ameleorate the Nigerian housing and infrastructural challenges.

References

| [1] | Agbola, T. and Olaoye, O.O. (2008). Labour supply and manpower development strategies in the Nigerian building industry [paper]. Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Ibadan, 15 January. |

| [2] | Carrero, E. (2006). Reforming Technical and Vocational Education and Training in the Middle East and North Africa: Experiences and Challenges. Luxembourg: European Training Foundation. |

| [3] | Carroll, C. (2013). The German dual vocational training model goes to America. Young German 24 July. Available: http://www.young-germany. [2017, January 2]. |

| [4] | Department for International Development (2007). Technical and vocational skills development - briefing. |

| [5] | European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training CEDEFOP, (2008a). Initial vocational education and training (IVET) in Europe review. |

| [6] | European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training CEDEFOP, (2008b). Evaluation of Eurostat education, training and skills data sources: European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. Available: www.cedefop.europa.eu/EN/Files/5185 [31 October 2016]. |

| [7] | European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training CEDEFOP (2010). Zooming in on 2010: Reassessing vocational education and training. Office for official publications of European communities, Luxemburg. |

| [8] | Fatimilehin, G. (2010). Nigeria: How unskilled manpower cost the country N900 billion yearly, Daily Independent 28 February. Available from: http://allafrica.com/stories/201100310958.html [2016, April 11]. |

| [9] | ILO (2012). Upgrading informal apprenticeship: A resource guide for Africa. International Labour Organisation. |

| [10] | Kogan, I. (2008). Education systems of Central and Eastern European countries. In: M. G, Irina-Kogan, and N. Clemens (eds.) Europe enlarged: A handbook of education, labour and welfare regimes in Central and Eastern Europe. Bristol: The Policy Press. |

| [11] | National Population Commission (2006). Nigeria 2006 population census. |

| [12] | Nworah, U. (2008). In search of skilled artisans The Village Square. Available: http://www.nigeriavillagesquare.com/articles/uche-nworah [2011, April 12]. |

| [13] | Roger, M. and Zamora, P. (2011). Hiring young unskilled workers on subsidized open-ended contracts: A good integration programme? Oxford Review of Economic Policy 27(2): 380-392. |

| [14] | Struwig F.W. and Stead G.B. (2010). Planning, design and reporting research. 6th ed. Cape Town: Pearson Education South Africa. |

| [15] | Tattara, G. and Valentini M. (2009). Can employment subsidies and greater labour market flexibility increase job opportunities for youth? Revisiting the Italian On-the-job Training Programme. Business and Economics. 42(3): 197-212. |

| [16] | Tashakkori, A. and Teddlie, C. (2010). Epilogue: current developments and emerging trends in integrated research methodology in Tashakkori, A. and Teddlie, C. Ed. Sage handbook of mixed methods in Social and behavioural research, California: Sage. |

| [17] | United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation Global Monitor Report (2010). Daily Champion. Available: http://allafrica.com/stories/201001280540.html. [2016, April 4]. |

| [18] | Werner, E., Núria, R., Ricarda, S. and Klaus, F.Z. (2012). A roadmap to vocational education and training systems around the world. Discussion Paper Series, No 7110, Institute for the Study of Labour (IZA). Available from: http://www.ftp.iza.org/dp7110 [2016, August 2]. |

| [19] | Wolter, S.C. (2012). Apprenticeship training can be profitable for firms and apprentices alike. European Expert Network on Economics Education- EENEE Policy brief 3/ 2012. |

| [20] | World Bank (2005). Expanding opportunities and building competencies for young people: A new agenda for secondary education, Washington, DC. |

| [21] | World Bank (2012). Doing Business in Nigeria, World Bank publication. Available: http://www.doingbusiness.org/ [2012, September 20]. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML