-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2017; 6(3): 63-77

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20170603.01

Knowledge Incubation in Informal Construction Practices in Tanzania: A Critical Review of the Literature

Justine Mselle , Samwel Alananga Sanga

Land Management and Valuation, School of Earth Sciences, Real Estate, Business and Informatics, Ardhi University, Tanzania

Correspondence to: Justine Mselle , Land Management and Valuation, School of Earth Sciences, Real Estate, Business and Informatics, Ardhi University, Tanzania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Formal and informal construction industries in developing countries are interlinked. The forward-backward linkage between the two provides a platform for conveyance of knowledge across sectors. Despite changes in house preferences and needs by client, informal craftsmen still dominate house construction in both sectors suggesting for the existence of informal incubation mechanisms. This study investigates the causal link that facilitates informal construction practices from sustaining dynamics observable in informal housing construction in Tanzania. The study is based on critical literature review supported by interpretative reasoning of previous secondary data. Despite some evidence on knowledge transfer within informal construction practices, there is scanty literature which provides a comprehensive analysis on the subject matter. However, the existing state of knowledge provide for the potential existence of “informal knowledge incubators” which acts as virtual breeding place for knowledge in informal construction. With this incubation, unskilled craftsmen undergo informal apprenticeship to become full skilled craftsmen though their technical abilities cannot be scientifically ascertained. Also, the forward-backward linkage between formal and informal construction industry has provided a platform for knowledge transfer. As a result, skilled craftsmen who have all qualities of entry into the formal construction sector end-up in the informal sector following unprecedented complexity in contractor’s registration process. This begs further for the re-examination of the contribution of informal construction sector on the overall economy.

Keywords: Tanzania, Developing countries, Knowledge transfer, Construction, Informal, Incremental housing

Cite this paper: Justine Mselle , Samwel Alananga Sanga , Knowledge Incubation in Informal Construction Practices in Tanzania: A Critical Review of the Literature, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 6 No. 3, 2017, pp. 63-77. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20170603.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In recent decades, the informal construction sector has gained popularity in developing countries such as South Africa, Nepal, Kenya and Tanzania in recent decades (Jason, 2008; Wells & Jason, 2010). The growth of informal construction is partly attributed to failed land delivery systems and rapid urbanization (Kironde, 1995; Kombe, 1994; Kessy, 2002). Informal construction is characterized by unregistered and unregulated contractors mostly trained informally (Mlinga & Wells, 2002). In Tanzania, informal housing construction has increasingly attracted higher income households contrary to conventional view that informality is a reflection of poverty (Lupala, 2002; Limbumba, 2010; Nguluma, 2003). These changes are typified by the co-existence of housing typologies with varied qualities and complexities. Given these dynamics, it is highly questionable whether the informal construction knowledge transfer mechanism can cope with these changes without severely compromising the overall quality of the building and the environment. There are limited empirical studies on informal knowledge transfer mechanisms and the extent to which informal craftsmen acquire knowledge and skills to cope with the rapidly changing construction sector in developing countries. This study develops a literature based informal knowledge incubation model in order to evaluate the owner-built housing construction practices in Tanzania. The paper starts with a general overview through a review of concepts and practices across the globe. From this general perspective, a conceptual model is then developed which is fitted into the context of Tanzania. Although the paper provides evidence of the operation of the knowledge incubation model, the discussion is still inconclusive. It would be convenient to further explore the current status of these incubators and their operations in developing countries in general.

2. Methodology for Literature Review

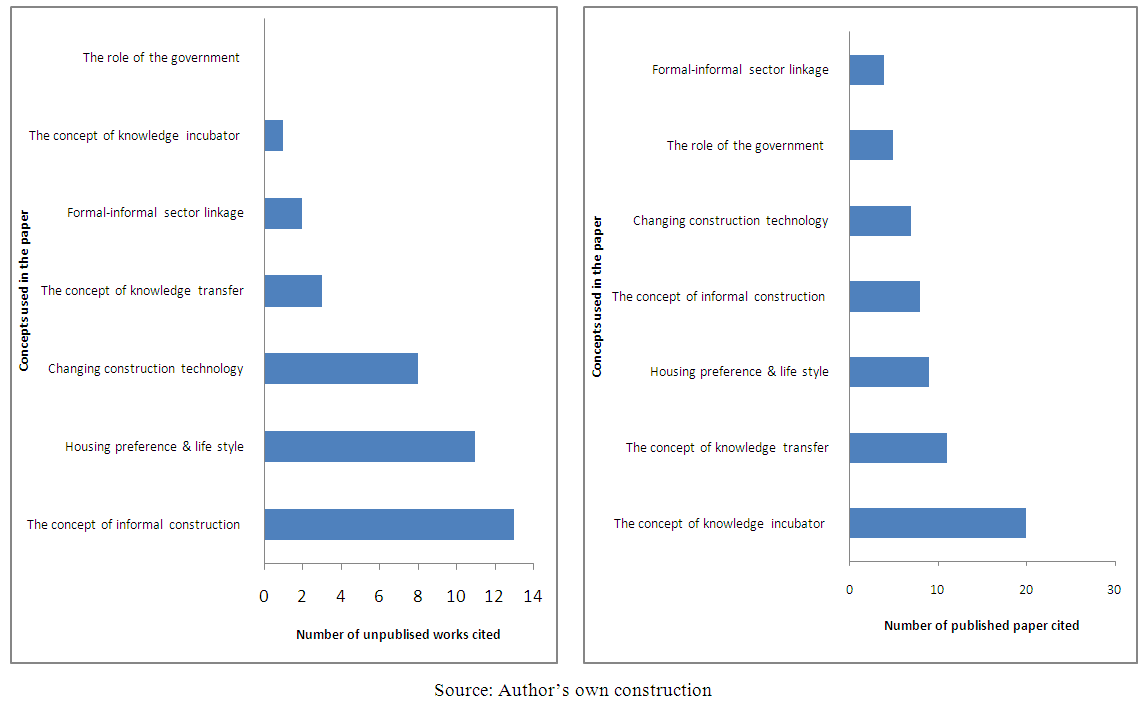

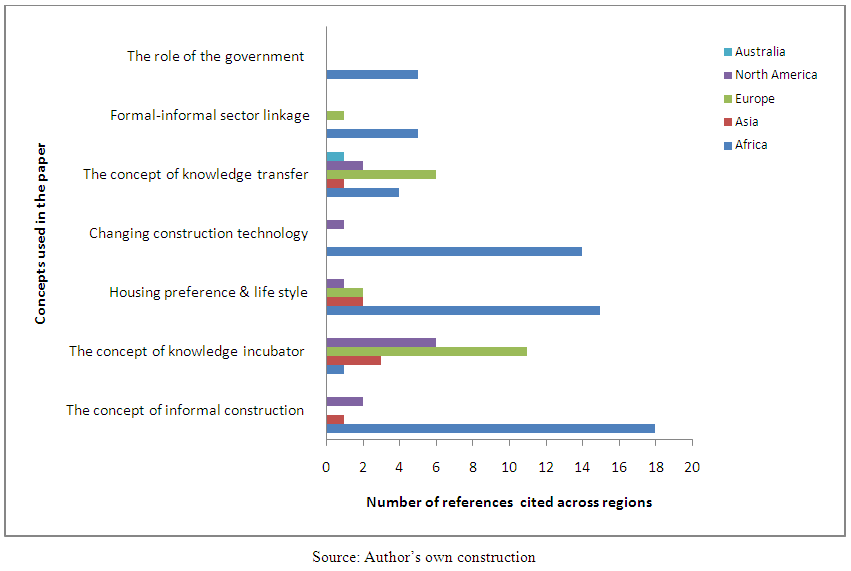

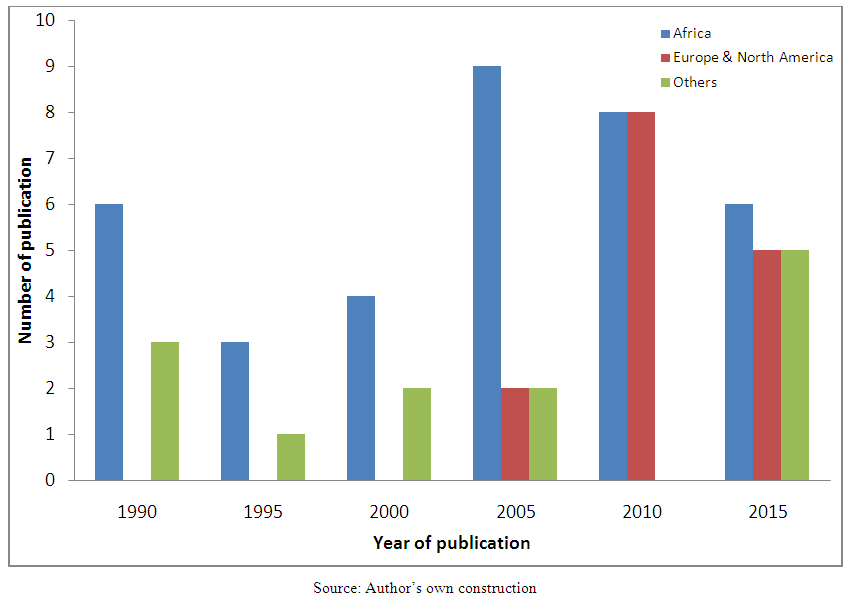

- The plan and methodology to review literature was based on predefined selection criteria. Inclusion into review for any paper or whether published or not depended on its publication status, if unpublished whether it is a PhD/MSc thesis or highly relevant material in the local library. Conceptually the reviewed covered the concepts of informal construction, knowledge incubator, knowledge transfer, housing preference and life style, role of the government in informal housing, formal and informal sector linkage and changing construction technologies. They were retrieved from Emerald Insight, Science direct, Taylor and Francis and Springer Link published during a period of 1995 to 2015 with exception of one classical paper from Turner (1967). Other literatures included were unpublished literature from Tanzania mostly consisted of seminar papers of 1980’s These papers were included in a list of reviewed papers because they addressed the government initiatives that affects knowledge transfer, simple construction technology and skills in Tanzania. Unpublished seminar papers and thesis were obtained from the university library where the authors work. Based on these strategies it was possible to retrieve other literatures using references cited from these published works through google scholars. As a results a total of 96 papers were retrieved and reviewed. After reviewing only 70 were cited in this work of which majority were peer-reviewed journal articles as shown in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. The number of published and unpublished work per concept |

| Figure 2. Number of cited work across regions |

| Figure 3. Number of cited work over time |

3. Informality in Construction and the Conception of Knowledge Incubators

- Informality describes “shadow” economic activity or activities not measured and registered in official market statistics or labour market (Heartz, 2012). Informality is also associated with illegal activities such as those of tax aversion or violation of labour standards and laws (Heartz, 2012; Sivam, 2002). According to La Porta & Shleifer (2014) informal enterprises accounts about half of economic activities in developing countries. In addition, De Soto (1989) described informal economy as untapped reservoir in the economy held back by regulations. Thus, in the context of construction sector, informality can be considered as activities which are unregistered, unprotected and unregulated within the construction sector. Informal construction activities are also a good vehicle for knowledge transfer (Teerajetgul & Charoenngan, 2006). The nature of a project and project team which normally comprises of people with diverse background and experience provides a good knowledge “incubation” environment (Davenport & Prusak, 1998). Therefore, incubatees can identify knowledge and skills used in one project, classify out of the bulk information, the most relevant skills to be used in the next project.

3.1. Informal Construction

- Many informal construction enterprises in developing countries play significant role in formal construction sector as well through material supply, labour and working as subcontractors. This argument is well supported by (Wells, 1998) who described that;“The informal construction sector comprises unregistered and unprotected individuals and small enterprises that supply labour and contribute in various other ways to the output of the construction sector.” (Wells, 1998, p. 1)Wells (2007), Jason (2008) and Mitullah & Wachira (2003) argue that informal construction is characterized by lack of formal employment and thus not directly protected by labour laws. Similarly, the World Bank (1984) associated informal construction with poor countries having housing shortage; therefore it could be used in a form of self-help program to construct low cost housing to combat house shortage particularly in rural areas (Mitullah & Wachira, 2003; Mlinga & Lema, 2000).

3.2. Knowledge Incubators

- In recent years, knowledge has been recognized as a strategic resource to improve productivity, innovation and competitive advantage (Teerajetgul & Charoenngan, 2006; Liyanage, Ballal, Elhag, & Li, 2009). Liyanage, Ballal, Elhag, & Li, (2009) and Nonaka & Takeuchi, (1995) described knowledge as information which is interpreted from individual and applied for a certain purpose. However, not all information can be classified as knowledge, but only those which can be applied for effective decision making (Phaladi, 2011). Further, Nonaka & Takeuchi (1995) and Ahmad & An (2008) classified knowledge into two types (tacit & explicit) based on their nature of existence. Tacit knowledge is held in the minds of people and thus very difficult to capture, store and share while explicit knowledge exists in company’s memos, procedures, database, specification etc. and can easily be captured, stored and shared. Capturing tacit knowledge within an organization require a conducive climate for knowledge transfer (Ribeiro, 2009; Nesan, 2012). Another perspective of knowledge was provided by Phaladi, (2011) who suggested that knowledge is dependent on human perception i.e. is both objective and subjective. Knowledge is perceived to be subjective due to the fact that it is context-dependent and its meaning depend on individual perception. Knowledge has also been described as strategic asset of a firm as it is difficult to imitate (Narteh, 2008) thus enabling a firm to gain competitive advantage over others. Employee of organization act as repository of knowledge in form of tacit and this knowledge may have been accumulated by an employee over years as part of his experience in that organization (Ly, Anumba, & Carrillo, 2005).The term knowledge incubator can be defined in terms of “technological incubators” to cover physical or virtue spaces upon which newly discovered technology is nurtured before being transferred to industries for commercial application or in terms of business incubator to describe a wide range of ubiquitous (Bergek & Norrman, 2008) and heterogeneous institutions (Scillitoe & Chakrabarti, 2010) in different contexts and with idiosyncratic objectives (Schwartz, 2013). Business incubators are generally geared towards nurturing entrepreneurship skills whether in physical or virtue space. As an English terminology, the term “incubator” refers to an instrument or machines that provide a certain artificial environment for the growth and development of something immature towards maturity. The term to “incubate” can be interpreted to mean "to maintain under prescribed and controlled conditions an environment favorable for hatching or developing (Winger, 2000; Branstad, 2010). In other context, the term has been used to mean “to cause to develop or to give form and substance to something”. To incubate a fledgling company or individual therefore, implies prescribing and controlling the conditions favorable to the development of a successful new organization or well knowledgeable individual capable of addressing the challenges in a particular field (Winger, 2000; Karapetyan & Otieno, 2011). In this study, the term “construction knowledge incubators” is therefore used to reflect the social, economic and environmental forces through which informal craftsmen or artisans acquire, develop and graduate as skilled craftsmen.

3.3. Knowledge Transfer

- Knowledge management is a response to the recognition of the importance of knowledge to the growth of firms and economies in general (Sheehan, Poole, Lyttle, & Egbu, 2005; McInerney, 2002; Eliufoo, 2005). Knowledge transfer is among the pillars of knowledge management which involves conveyance of unique information from one place, individual or source to another (Liyanage, Ballal, Elhag, & Li, 2009; Sun & Scott, 2005). Although the differences between knowledge transfer and knowledge sharing are still debatable, the two terms can be differentiated by the information flow where knowledge sharing is a two-way traffic while knowledge transfer is a one-way traffic (Paulin & Suneson, 2012). Informal craftsmen as described above emerge from informal knowledge transfer mechanisms where knowledge is being acquired through learning by doing or by long terms observation and practicing (Mitullah & Wachira, 2003). According to Adowole, Siyanbola and Siyanbola (2014), different societies have practiced “knowledge transfer” since time immemorial though in an ad hoc manner. However, as a research concept, knowledge transfer is considered relatively younger than human history just in line with the concept of knowledge management. As a result of this newness, very little understanding exists on its efficiency at individual or even organisational level in many developing countries.Knowledge transfer is individually construed due to the fact that it is highly dependent on individuals’ knowledge “Absorption Capacity” (Phaladi, 2011). Therefore, for effective knowledge transfer to happen, it must be absorbed by recipient and assimilated into new knowledge that can improve productivity or a specific process. Furthermore, Nonaka & Takeuchi (1995) suggested that the effectiveness of knowledge transfer depends on the type of knowledge i.e. whether tacit or explicit. Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) views form a base upon which other researchers such as Windsperger & Gorovaia (2010) came to suggest that the choice of knowledge transfer mechanism depends on information richness which is a best criterion to judge if knowledge is tacit or explicit.

4. Housing Dynamics in Developing Countries

- Despite the changing construction technology, housing preferences and construction materials, construction contractors in developing countries heavily rely on informal craftsmen. This potentially suggests that housing construction continue to be dominated by informal practices in which informal craftsmen determine both quality and construction cost. The use informally trained craftsmen in formal construction projects suggests that informal knowledge transfer mechanisms potentially breeds "acceptable quality" craftsmen (Mlinga & Wells, 2002). That is, there are some unobservable and unintentional knowledge incubators that nurtures construction skills among informal construction labourers. This section examines the rationale for this proposition.

4.1. Changing Housing Preferences and Lifestyle

- Traditionally, different tribes had different preferences on how houses were designed and constructed (Mwakyusa, 2006). The design reflected culture and belief of the society as it was reported by Agboola & Zango (2014) that;“Designs in traditional architecture reflect the cultural lifestyle of the people and represent the symbols of the heritage of the residents. Hence response to the material, spiritual, and social design of the society cannot be over-emphasized” (Agboola & Zango, 2014, p. 62).Over time, changing technology, religion and the coming of colonialism contributed to the changes of house types in many Africa countries. Agboola & Zango (2014) described religion, changing lifestyle and external contact with other people were among factors that influenced house type in Sub Saharan African (SSA) countries. Upon attainment of independence, many African countries adopted stringed urban control policies which considered informal housing as only temporary housing subjected to demolition and eviction. The approach to housing immediately after independence was massive government housing schemes in planned areas. These housing programmes of non-incremental nature (developer-built housing) were implemented in many developing countries in the 1950's and 1960's but proved a failure (Majale, Tipple, & French, 2012; Wakely, 2014). Currently, the conventional housing supply which rely on formal housing finance in Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries have largely been replaced by incremental or self-built housing approaches (ShoreBank International, 2011; Neves & Amado, 2014; Samaranayake, 2012; Raman & Narayan). As a result of this policy shift, housing types in formally planned areas and in informal settlements do not differ significantly. The housing preferences and lifestyle changes may have impacted the informal craftsmen capabilities to provide housing in informal construction activities. The facts that craftsmen continue to dominate regardless of diverse choices that owner-builder make suggest potential construction knowledge incubation in informal construction practices.

4.2. Changing Role of the Government and Informal Construction

- The World Bank viewed informal housing construction as the one directly related to informal settlement and simple housing construction (Wells, 2001). This argument was criticized by Mitullah & Wachira (2003) who established that informal construction was increasingly applying sophisticated technology to construct complex commercial buildings both in formal and informal areas. Construction industry in developing countries experienced major changes in the 1980’s due to Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) as reported by (Wachira, Root, Bowen, & Olima, 2008). One example was, Kenya which experienced huge reduction of public spending in construction. As a result, many organizations started shading off their employed labour thus increasing the use of casual laborers (Wells & Jason, 2010). According to Wells & Wall (2001) the decline in formal construction paved ways for informal construction to pick-up because many shed-off employees established informal construction “firms”.Although housing construction takes place in both planned and unplanned areas (Wells, 2001) only constructions activities in planned areas are regulated. However, informal construction outweighs formal ones in terms of number of projects executed (Mitullah & Wachira, 2003). In formal areas, informal contractors supply labor to execute works to formal contractors (Wells, 2007). Due to such linkage, Wells (2001) criticized the argument that informal construction is inferior to formal construction. There could be several reasons for the diminishing control of the government in the housing construction process such as shortage of surveyed plots (Wells, 2001; Mlinga & Wells, 2002) and the construction cost-flexibility offered through the incremental nature of informal construction practices (Alananga, Lucian, & Kusiluka, 2015). The basic question is whether this diminishing control of construction activities provided an environment for informal construction knowledge transfer or not. The fact that some formal workers in government project established their own informal “firms” provides some evidence that these practices embed some knowledge incubation traits.

4.3. Emerging Formal-informal Sector Linkages

- For the last two or three decades, The construction sector has witnessed the shed-off of direct employees and shift to out-sourcing of labor from informal construction due to fluctuation in labor demands and strict labor laws (Wells, 2001; Wachira, Root, Bowen, & Olima, 2008; Mlinga & Wells, 2002; Wachira, 2001). The shed-off and active employees from formal construction sector established informal construction enterprises (Mlinga & Wells, 2002). As a result permanent recruitment of workforce in the construction industry has diminished while subcontracting and intermediation has increased (Wells, 2001; Wachira, 2001). Intermediaries normally work as a bridge both to principle contractors and subcontractors to mobilize workers to formal construction site by recruitment, control and supervision (Wachira, 2001). In most cases these workers were recruited from friends, relatives and other craftsmen whom an intermediary had a record. Intermediaries create a linkage between formal (principle contractor or subcontractor) and informal construction craftsmen. These formal-informal sector linkages provide further evidence of the nurturing environment for construction knowledge incubators.

4.4. Changing Construction Technologies

- Traditionally, construction reflected locally available materials, skills; climate and space need in a particular society (Mwakyusa, 2006; Lyamuya & Alam, 2013; Agboola & Zango, 2014). The coming of eastern traders and western colonialism replaced some traditional materials with modern one principally due to prohibitive regulations and preference for modernity (Agboola & Zango, 2014). Changing from traditional house to modern house require a shift of craftsmen who had traditional knowledge on materials and construction techniques towards modern construction materials and techniques (Mwakyusa, 2006; Delanote, 1981). The key challenge here is when the demands for modern construction skills far outweigh its supply. Informal craftsmen may declare skills they do not have as long as they can get somebody to train them even for a very short time or can bid at a relatively higher price so that they subcontract the works and reap the marginal profit. Alternatively, the craftsmen may bid too low a price and ultimately fail to accomplish the task as required. These potential risks imposed by the informal nature of the construction workforce could have serious quality implications which have not yet been investigated in developing countries.

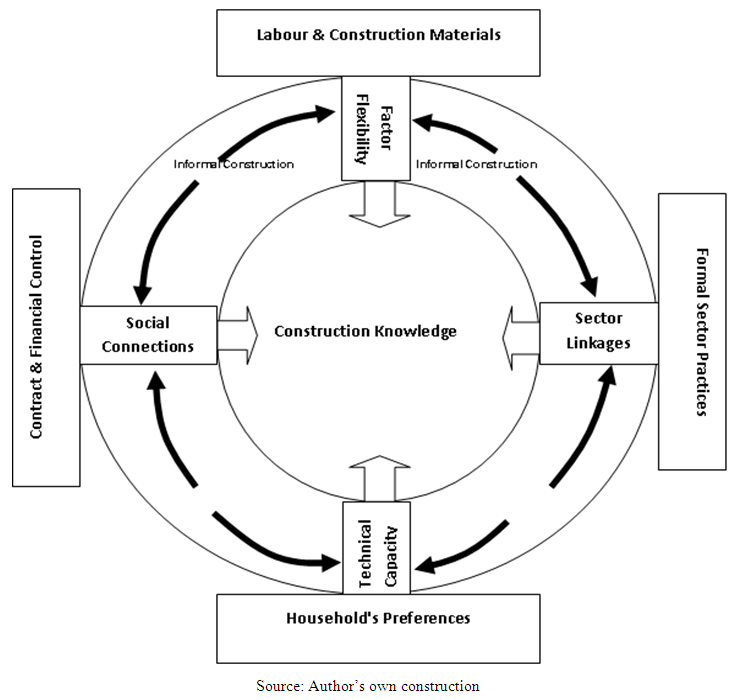

5. Informal Construction Knowledge Incubation Model

- The above changes that happened all over the developing world can be captured through Informal Construction Knowledge Incubator (ICKI) model presented in Figure 4. The lower part of the ICKI model suggests that changes in housing preferences and urban forms can easily be accommodated through technical competency acquired through informal knowledge transfer. The assumption being that the subject construction sector comprises an informal incubator that is capable of hatching competent craftsmen. Since the informal housing sector has managed to provide housing for a long time and housing in formal and informal sector do not significantly differ (Lupala, 2002; Nguluma, 2003), it can be argued that the informal sector is a good incubator of construction knowledge for all technical requirements that meet the clients' preferences. In order to cope with changing housing forms and clients’ preferences, craftsmen may require further training only above what they currently know and which might be difficult to acquire through learning by doing. Specifically, they would require knowledge on the theoretical back-ground of construction concepts and their application, rules and regulations governing the construction sector and other land related laws.

| Figure 4. A model of Informal Construction Knowledge Incubators (ICKI) |

6. Construction Knowledge and Housing Dynamics in Tanzania

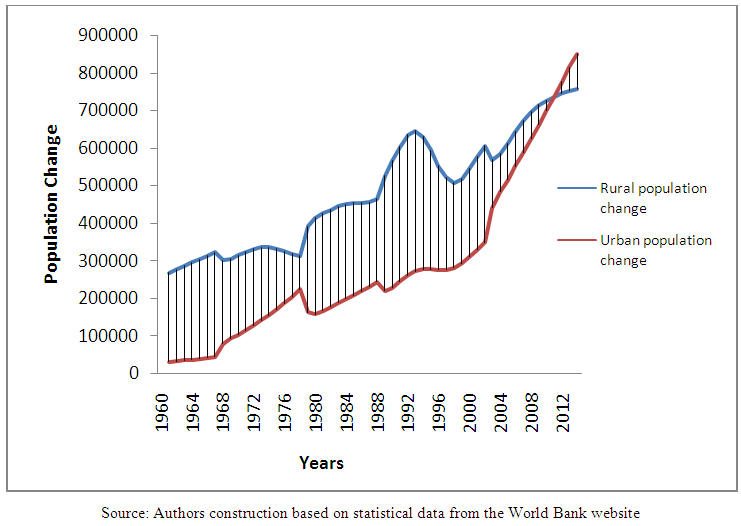

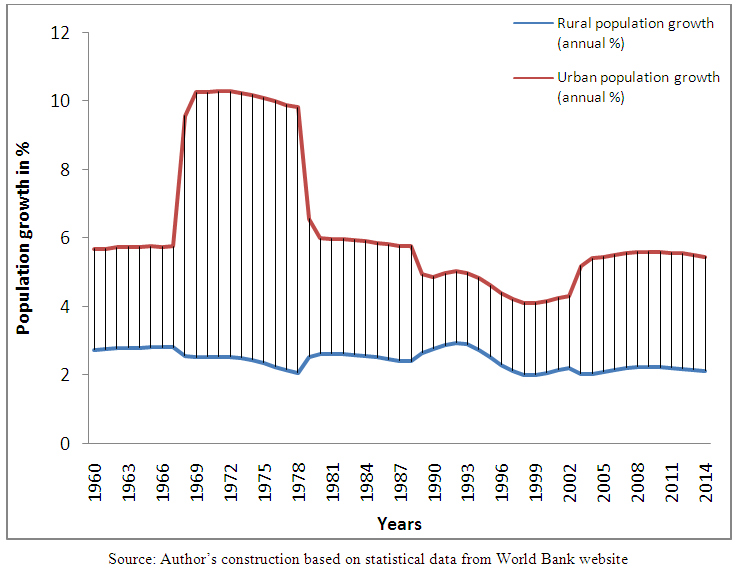

- Before independence, most housing both in rural and urban were constructed of traditional materials as reported by Delanote (1981). Soon after independence “Better housing” programme was established to improve housing condition (Kironde, 1994; Nguluma, 2003). In Dar es Salaam for example, many Africans were living in squatter areas of Buguruni, Keko and Kurasini (Kironde, 1995; Kironde, 1994). In order to clear slums and squatters for implementation of “Better houses” programme, the government instituted the National Housing Corporation (NHC) and Tanzania Housing Bank (THB) in 1962 and 1973 respectively (Kessy, 2002). The focus in urban areas was rental or hire purchase flats which were implemented in areas where slums had to be cleared i.e. Magomeni, Mwananyamala, Kisutu, Temeke and Buguruni (Kessy, 2002; Maganga & Ndjovu, 1981). Better housing went hand in hand with “self-help” program where prospective house owners were trained to organize themselves to construct their own houses (Schilerman, 1981; Bananga, 1981; Karlsson, Salomon, & Siroiney, 1981).The early post-independence housing initiatives were formulated in line with the population structure of the country at the time. The majority of Tanzanians were living in rural areas as shown in Figure 5. In mid 1960s' and 1970s’, Tanzania experienced a rapid urban population growth as indicated in Figure 6. As a result of this population surge, the state-built housing supply strategy failed by the end of 1960s opening-up rooms for private developer and informal settlement growth (Kulaba, 1981; Hayuma, 1988). In the 1970s, there was a global recognition and acceptance of informal settlements as part of urban housing stock (Kessy, 2002; Nguluma, 2003; Turner, 1967). Urbanisation however, increased the proportion of low income household among urban immigrants whose housing demand are skewed towards cheaper and close-to-working place informal accommodation (Kulaba, 1981; Nguluma, 2003).

| Figure 5. Population Change in Rural and Urban Tanzania; Compared |

| Figure 6. Annual change in population in rural and urban Tanzania |

6.1. Changing Housing Preferences and Lifestyle in Tanzania

- Peoples’ preferences are shaped by the beliefs, norms, culture and what is happening globally. For example, Nguluma (2003) found that most of coastal areas had “Swahili type” houses constructed with long corridor dividing a house in two equal parts. The design and layout of Swahili houses reflected spatial use and belief of traditional societies. Similarly, the imposition of new religions (Islam & Christianity) was reflected on changes in house types and consequently in urban types across cities in Tanzania. Recently, there are increasing changes in housing preference in terms of house type, number of storey, building materials and house size both in formal and informal areas. Informal areas which used to have single storey buildings were being transformed into modern houses of different forms including multi-storey buildings. Based on the ICKI model, informal construction practices incubates skills and knowledge transferable to unskilled worker to accommodate the rapidly changing clients’ preferences and lifestyles. Evidences from Mitullah & Wachira, (2003) and Wells & Wall, (2001) indicated that changing housing preferences and lifestyle have not impacted seriously on the demand and supply of informal craftsmen and instead craftsmen skills seems to have improved in response to client’s demands and preferences (Nguluma, 2003; Wells & Jason, 2010; Mitullah & Wachira, 2003). The flexibility that informal craftsmen have displayed in response to changing housing preferences and lifestyle across the developing world suggests significant training cost-saving inherent in informal incubators if they exist.

6.2. Changing Roles of the Government in Tanzania

- Wells & Wall (2001) noted that structural adjustment program (SAP) lead to reduction of government public spending which affected many sectors including construction. As a result, a rapid increase in the use of informal contractors (informal system) started to take place both in formal and informal construction projects. The 1980’s policy shift from the government as a key player in housing construction towards liberalisation of major means of production encouraged the growth of informal construction. Wells & Wall (2001) noted that the existing systems of housing construction in Tanzania were far away from the formal practices used during colonialism and even in early post-independence era. In their own words they noted that;“The majority (by volume) of new buildings constructed in East Africa are produced through an ‘informal system’ which is significantly different from the traditional construction procurement system, established during the period of British colonial rule and used on the majority of public sector projects” (Wells & Wall, 2001, p. 5).Apart from the laxity of regulations, there are three additional reasons that fuels informal construction practices: First, informality allows a client to have hands on material purchases, construction supervision and quality management; second, it allows an incremental construction approach, a flexible approach to many clients (Alananga-Sanga & Lucian, 2015); and third; many construction contractors do not operate informally out of will or inability to pay certain fees, rather out of cumbersome registration practices (Wells, 2007; Mlinga & Wells, 2002). Their technical capacity gives a platform for the growth of informal construction especially where they collaborate with other semi-skilled crafts and contribute to informal mentorship. Based on the preceding observations, it is evident that informal incubators flourish well in an environment where the government not only play a passive role but also when it “actively” complicates the formalisation process to deter even those who are well qualified from being statutorily recognised.

6.3. Emerging Formal-informal Sector Linkages in Tanzania

- A number of researchers have established the linkage between formal and informal construction and how the linkage facilitates knowledge transfer between such two industries in Tanzania. Findings by Mlinga (2001); Wells (2001) and Mitullah & Wachira (2003) argue that collaboration between formal and informal construction has benefited the later because it has enabled informal craftsmen to inculcate experience and acquire skills on new materials and construction technology. Likewise Mitullah & Wachira (2003) argue that, the experience from collaboration enables the informal unskilled workers to be employed not only for small residential buildings but also for complex commercial buildings such as hotels and apartments both in formal and informal areas. As they execute more complex projects, they are exposed to new construction materials, technology and management thus chances to transfer such skills to informal construction increases.

6.4. Changing Construction Technologies in Tanzania

- Before independence, most housing units in Tanzania were constructed from traditionally available materials and technology and reflected the traditions and cultures of the society into which each was situate (Nguluma, 2003). Soon after independence, the government established a strategy for “Better housing” using permanent construction materials and modern technology. Changes in modern informal construction practices seem to efficiently accommodate informal knowledge transfer traits as described in the following subsections.

6.4.1. Changes in Housing Construction Modalities

- Due to the fact that most housing construction was organized within a family, traditional construction practices provided a very conducive platform for apprenticeship, knowledge incubation and the ultimate transfer from one generation to another (Nguluma, 2003). These traditional organisational structure though advantageous as far as knowledge transfer is concerned, it prevented external knowledge assimilation which is important if informal knowledge incubators are to perform efficiently. In modern informal construction, construction is organised slightly far away from the family boundaries, i.e. through formal or informal contractors. The participation of informal contractors to formal construction market is either through sub-contracting labour supply or having sub-contracted a certain piece of work such as masonry, finishing and carpentry. This access to formal undertakings has therefore, strengthened the confidence of clients to the informal craftsmen and thus increased their credibility. Apart from few organised informal contractors, the sector is dominated by individual craftsmen with simple tools and equipments and operates on demand (Magigi & Majani, 2006; Jason, 2008). Due to the use of simple tools and equipments the quality and productivity of informal contractors has been a matter of concern. This is evidenced by findings from Mitullah & Wachira (2003) who reported that quality control in most informal construction was carried out by the owner; however a findings by Nguluma (2003) questioned the quality of workmanship in incremental housing especially the finishing. This signifies that, although craftsmen in Tanzania might be technically competent to transfer technical skills and expertise, in the face of rapidly changing construction technologies, their knowledge competency need to be augmented with formal training.

6.4.2. Changes in Housing Construction Materials

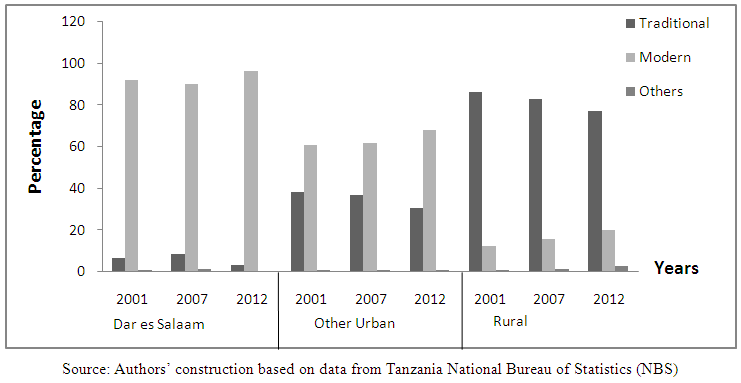

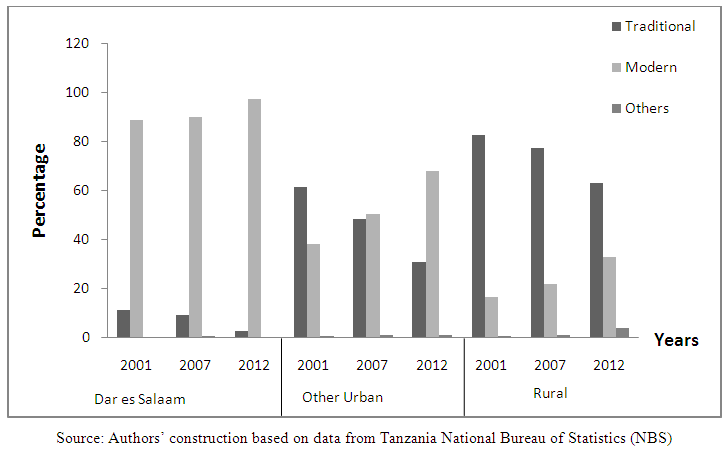

- In Tanzania high quality housing can be found in informal settlements where physical infrastructure is either lacking or is in severe state of disrepair (Limbumba, 2010; Lupala, 2002). Figure 7 & 8 indicates percentage of house constructed from traditional and modern construction materials both in urban and rural areas as recorded in Household Budget Survey (HBS) of 2001 and 2012. Between the two periods, the data suggest that the use of modern construction materials in urban areas has increased while the use of traditional materials has declined. An average of 70 percent of houses in urban areas was constructed using modern materials with exception of Dar es Salaam where houses constructed using modern materials was around 98 percent. Houses constructed using modern materials (block or burnt brick, modern finishing) in rural areas were increasing though at a very slow pace, only 35 percent of houses in rural were constructed using modern materials. This preference on modern materials is also captured in Nguluma (2003), as follows;“We bought a pole and mud structure in 1974. We lived in the house until 1990 when we decided to demolish it and build another structure by using concrete blocks. The motive behind demolishing the first structure and building a completely new one is because the pole and mud structure was deteriorating. Toilets were located outside the house and sleeping rooms were small. We had the urge to own a modern house, a house that suits an urban way of living. In the new house we made a provision for a sitting room, dining room, kitchen, toilet and bathroom. We also provided for large windows to allow enough light and cross ventilation. We are happy that we now own a modern house (Nguluma, 2003, p. 114).Generally, the 2001 and 2012 HBS data show that there was a decline in the use of traditional materials in favor of modern materials in both urban and rural areas. The increased transformation from traditional to more durable and modern houses calls for the acquisition of knowledge on modern construction materials and technology to cope with increasing demand (Nguluma, 2003). Apart from the cost implications, construction materials dynamics imply increased coping difficulties among informal technicians (who informally and over time acquire their skills) to immediately respond to changing demands. Despite these dynamics, there has been no serious call for formal training among local skilled craftsmen. This suggests that informal incubation mechanism provide adequate knowledge resources to cater for changing construction materials. Empirical on this proposition is however lacking thus calling for a research along these lines.

| Figure 7. Comparison between traditional and modern floor materials from different locations |

| Figure 8. Comparison of traditional and modern wall construction materials between different locations |

7. Discussions and Policy Implications

- Although it is well known that construction knowledge can be transferred from experienced craftsmen to unskilled craftsmen, the mechanisms that actually operate to impart knowledge from one generation to another and how long such process should take is not clear. Under formal apprenticeship, the unskilled craftsmen work under the supervision of a senior craft and once they graduate they can work independently. If this process is implemented in informal construction, it can be considered a step towards formalisation. By formalising knowledge transfer linkages between formal and informal construction works, the work quality gaps are likely to disappear. In this last section some policy implication of the discussion are drawn based on the four major sources of incubation identified under the ICKI model.

7.1. Inter-sector Linkages

- According to Wells (2001), the decline of NHC and THB activities in Tanzania led to the reduction of workload to large contractors thus forcing the adoption of austerity measures including axing of some permanent employees to cut operation cost. Large contractors’ strategies shifted from permanent employee towards sub-contracting and intermediaries through hiring of crafts in form of “labour-only contract”. Furthermore, redundant workers from formal construction started working as informal contractors to construct houses for private clients through labour supply and as sub-contractors of the formal contractors (Mitullah & Wachira, 2003; Aikaeli & Mkenda, 2014). This collaboration did not only build the economic capacity of informal contractors but also facilitated knowledge transfer between formal and informal construction industry. These observations provide significant evidence that informal incubators do not only exists but also function efficiently in terms of cost reduction.

7.2. Technical Capacity

- This paper suggests that informal incubators flourish well in an environment where the government not only play a passive role but also where it “actively” complicates the formalisation process to deter even those who are well qualified to formalize their enterprise. Immediately after independence, the government of Tanzania instituted a formal education system to train artisan, technicians and engineers as a long term strategy to curb skill shortage. In line with the formal education system, laws and regulations for registering and regulating enterprises that executed construction activities (contractors) were enacted by 1972 and later repealed by Contractors Registration Act No. 7 of 1997. If registration is based on technical merits, many of the craftsmen in the informal sector would have qualified for registration. However, a research by Wells (2000) and Mlinga & Lema (2000) found that there were many technically qualified informal contractors who chose the route because of bureaucracy in registration and tax system. These “registration-qualified” informal contractors are therefore the real construction knowledge incubators as long as they are willing to transfer their skills to helpers with whom they are working with. Amending the laws by reducing the legal requirements to register as a contractor and reducing certain taxes and fees falling onto contractors could significantly increase the registration rate at least at the lowest radar of technical competency.

7.3. Social Connectivity

- Informal housing approaches create a personal relationship between the built unit and the owner. Thus, self-builders view their houses as not only shelter but also a means of social standing and prestige (Boamah, 2010; Harper, Portugal, & Shaikley, 2011). Conceptualising along those lines, many self-builder would like to have a full control of the construction process. Unlike formal construction where the contractor has a fixed role based on the contract, informal construction contracts hardly exists and when they do they are only verbal and highly flexible. This flexibility builds a strong social relationship between the client and the craftsman given the longer duration that many such projects are implemented which act as a conflict shock absorber. Evidence of social connectivity is in the way informal craftsmen secure job as reported by Malony (2008) who established that many informal craftsmen secure works through friends, relatives and previous customers. This social relationship in job securing provides incentive to transfer knowledge from senior craftsmen to new entrants in the industry. Instead of severing this link, relevant authorities in developing countries need to develop ways through which it can be strengthened specifically through making it mandatory for formal projects to hire and train unskilled workers from the informal sector. Therefore, increasing the formal links through which informal craftsmen can secure jobs enhances not only their income status but also has the potential to enhance their construction skills competence.

7.4. Factor Flexibility

- Another important observation from this study is that the flexibility that informal craftsmen have displayed in response to changing housing preferences and lifestyle across the developing world suggests significant training cost-saving inherent in informal incubators if they exist. Alananga-Sanga & Lucian (2015) established that owner-built incremental housing construction is preferred among low income household because of factor flexibility where projects can be stalled at no significant additional costs. Further, clients may be interested with the flexibility in informal constructions because neither specific budget nor construction period is pre-specified. This flexibility allows the client to procure materials and hire labourers either on piece work or on daily bases to work on site based on their financial capacity. The main shortcoming of this incubation mechanism is that craftsmen who are exercising their expertise for the first time may fumble over their works leading to severe quality problems. Similarly, many owner-builders end up with some construction skills for which they are not likely to use them in their career. In economic terms, all this is wastage of resources which require the attention of policy makers.

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

- This study advocates for the identification and formalisation of the informal construction knowledge incubators to facilitate long term survival or sustainability of locally bred construction technologies in cities of developing countries. The knowledge incubation model assumes that informal construction knowledge transfer mechanism function through at least four channels. The first being factor flexibility whereby informal construction practices allow owner-builders to exercise considerable control over cost-push factors. The second knowledge incubator is sector linkage which allows informal construction craftsmen to be part of formal projects. This link provides an important impetus in the life of informal practices and for the case of Tanzania, it has resulted into the visual match between formal and informal housing. Social connectivity is the third knowledge incubator where works are contracted informally through some social connections thereby shaping long-term knowledge flows. The social connections act like a shock-absorber in case of misunderstanding between the client and the craftsmen. The last incubator that has been discussed in this paper is technical capacity which is challenged by the non verifiability of technical qualifications declared by informal craftsmen. That is the level of their expertise can be neither verified nor guaranteed. In fact, the craftsman is the guarantor of the work he will perform. As many people opt for owner-built informal construction, the number of trustworthy connection is likely to decline and potentially this approach is prone to exhaustion over a certain range of utilisation and time. Although there has been no evidence suggesting serious problem under this approach, the literature so far has noted some quality problems that could be the main source of hidden conflicts which are however, resolved at local levels. These potentialities suggest further that the quality of the built environment could be compromised in the future and immediate actions are required to remedy the informal knowledge transfer mechanism in favour of formalising all knowledge incubators specifically under the rapidly changing construction technologies. Based on the findings the study therefore recommends that a research to be carried out to collect empirical findings which examine the extent of knowledge and skills of informal craftsmen and its equivalent to formally acquired skills, assess the mechanisms used to transfer knowledge informally and constraints experienced in informal knowledge transfer.

Limitations of the Study

- Although this study has developed a simple framework for analysing informal construction activities in relation to knowledge incubation, the limited number of literature reviewed throughout the developing world (other than Tanzania) along these lines makes the application of the developed model only sufficient within the context in which it was developed. The adoption of the model to understand knowledge incubation in other developing countries may require additional consideration of specific housing policies as implemented since the emergence of informal construction practices in those countries.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML