-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2017; 6(2): 56-62

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20170602.03

Important Resources and Competences (IRCs) of Foreign Contractors in Tanzania Construction Industry

Harriet K. Eliufoo

School of Architecture Construction Economics and Management, Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Correspondence to: Harriet K. Eliufoo, School of Architecture Construction Economics and Management, Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

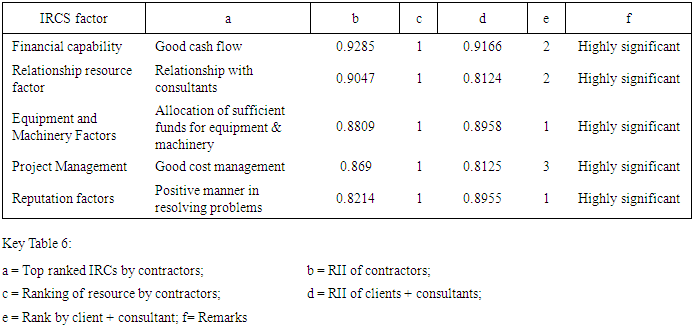

The article has explored Important Resources and Competence (IRCS) factors of foreign contractors in the Tanzania construction industry as an attempt to explain their market share value. A survey was made of foreign contractors, consultants and clients’ representatives of what are the perceived variables that give foreign contractors a competitive advantage in the industry. A total of 53 respondents were involved in the study. The result show the top ranked IRCS factors contributing to foreign contractors competitive advantage are: financial capability particularly, good cash flow; good relationship with consultants, ability to allot sufficient funds to plants and equipment, good cost management and capacity to positively resolve problems.

Keywords: Core competence, Competitive advantage, Construction, Tanzania

Cite this paper: Harriet K. Eliufoo, Important Resources and Competences (IRCs) of Foreign Contractors in Tanzania Construction Industry, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 6 No. 2, 2017, pp. 56-62. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20170602.03.

1. Introduction

- In today highly competitive environment, business organizations need to act fast in order to secure their financial situations and their market positions. Firms are continuously striving for ways to attain a sustainable competitive advantage. They need to count more on their internal distinguished strengths to provide more added customer value, strong differentiation and excel on “core competences” [1]. Hence strategy for excelling has to shift from competing for product or service leadership to competing for core competence leadership. In Tanzania foreign contractors though constitute less than 1.28% of all 8,198 registered building contractors in the country, execute about 63.42% of total value of large and medium-sized contracts [2]. Local contractors carry out 94.72% of all registered projects while only 5.28% are done by foreign contractors. Evidence has shown value of projects done by foreign contractors outweighs that of local contractors. Adopting the concept that core competency is about knowledge on successes or failures in managing knowledge resources [3]; the ability to operate efficiently within the business environment and respond to challenges [4], this article investigates core competence variables inherent in foreign contractors that may explain their superior position in the market share of construction projects in Tanzania. It anchors on Cheah et al.’s [4]) notion of facilitators of core competence, “Important Resources and Competences” (IRCs). The article explores whether performance of foreign contractors as reflected in the share value of projects is attributed by their embracement of these important resources and competences.

2. Literature Review

- Core competenceCore competence reflects an organization's strength essential for a sustainable competitive advantage [5, 6], characterized as dynamic, slow changing and cumulative [5]. As companies differ in abilities to select, build, deploy, and protect core competencies so are the differences in corporate performance [1]. Leonard-Barton (1992) cited in [7], defined core competence as that factor which differentiates a firm from its milieu; a result of “collective learning” processes manifested in business activities and processes [8]. Core competence has also been explained to constitute: shared vision, cooperation and empowerment [9-12].Core competence represents a collection of competencies that is widespread in a corporation as a result of interaction between different Strategic Business Unit’s (SBU) competencies [11]. It engulfs skills and areas of knowledge that are shared across business units and arise from integration and harmonization of SBU competencies [7, 8]. Core competence reflects collective learning of an organization, coordination of diverse production skills and integration of multiple streams of technologies [1]. The concept has also been discussed variably by scholars in multiple directions [7, 13, 14]. Identification of competences in an organization by itself is not enough; the critical task is to assess them relative to those of competitors. Although a firm may identify a host of competences that it performs better relative to its competitors, not all competences are “core”. Core competence is that competence which allows a firm a superior advantage. It is what the company does better than, or differently from, any other company and is the source of whatever success it enjoys; and definable only in relation to the competence of others [15]. It hence follows that one cannot delineate core competence from “competitive advantage”.Competitive advantage Competitive advantage for an organization is provision of that “value” which motivates customers to purchase its products or services rather than those of its competitors. [16, 17]. It requires effective integration of several different types of information, gathered and processed in different organization’s departments [18]. When a firm can do something that rival firms cannot do, or own something that they desire, that represents competitive advantage [19]. Innovation is cited [20] as a typical facilitator of competitive advantage. Important Resources and CompetencesImportant resources and competences (IRCs) is a concept adopted from Cheah et al’s [4] conceptual model of how large construction firms can improve competitive advantage. It represents variables viewed to instigate competence for organizations. Cheah et al., [4] identified 5 IRC variables: i) relationship resource (guanxi resources), ii) technological and innovative capabilities, iii) financial capability, iv) project management competencies and v) reputation.Relationship resource as an IRC variableThis refers to a firm establishing relationship with stakeholders relevant to its operation. For a contracting firm it may include: government or regulatory bodies, financial institutions, research institutes, sub-contractors, consultants and suppliers. The significance of this resource is emphasized especially where the industry has a high degree of institutional uncertainty such as when there is lack of fully developed legal and regulatory systems, excessive bureaucratic procedures, lack of legal enforcement and supervision [4]. Technological and innovative capability as an IRC variableThis is considered a catalyst for competence enhancement since possession of technology is important to the maintenance of competitive position in most organizations. For some it is key to competitive advantage [20-22]. Technological innovation has also been linked to growth of market share and reduction of construction costs [23]. Financial capability as an IRC variableThis refers to firm’s ability to access to finance, credit, and aptitude for strategic investment and good financial management. The notion being, financial capability is a contributor to competitive advantage of a firm [4].Project management competencies as an IRC variableThis variable entails competencies that ensure a project is completed on time, within budget and at a desired quality [4]. It encompasses a firm excelling in schedule, cost and quality management. Possession of good procurement and contractual management acumen are also an essential part of this variable. Reputation as an IRC variableCorporate reputation reflects the overall estimation in which a company is held by its constituents; it is a perception of company’s past actions and future prospects when compared with other leading rivals [24, 25]. It reflects a firm’s relative standing internally and externally [26]. It is thus perceived positive reputation is reflected in customer confidence and hence results to competitive advantage over others.

3. Research Methods

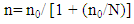

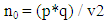

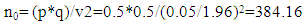

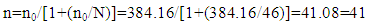

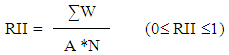

- The five IRC variables of core competence [4, 27] were used to assess foreign contractors practicing in Tanzania. A survey administered was structured in 2 parts: first part designed to obtain general information about the companies and respondents. The second part identified foreign contractors’ areas of core competence from the perspective of clients, consultants and contractors. The Likert scale of four ordinal measures was adopted in evaluating responses. The respondents were clients, consultants and foreign contractors that had construction projects ranging from USD $1 million to USD $100 million in Tanzania. The respondents were initially identified and selected from the Tanzania Contractors Registration Board’s (CRB) list of registered construction projects in Tanzania from 2013 – 2015. These years where selected as year 2015 reflected a time where the construction sector’s contribution to GDP was at a peak not precedent for many years. This thus represented an information rich period. The industry contributed 13.6% to Tanzania’s GDP during 2015, reaching almost USD $6 billion whereas in 2010 the sector accounted for only 7.8% of the country’s GDP equivalent to USD $1.6 billion [28]. As the population is known, the sample size was established using the formula indicated (see equation 1) The sample size was calculated as follows [29]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Conclusions

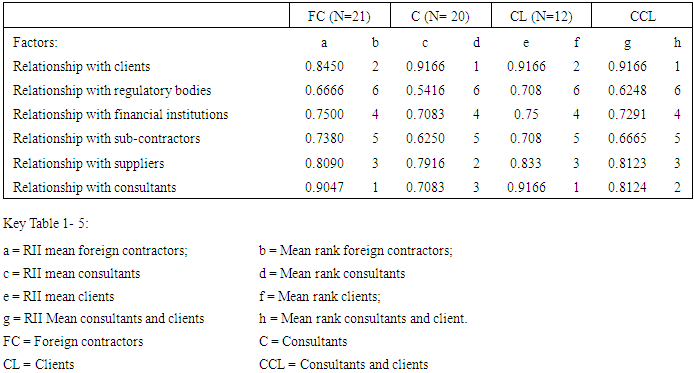

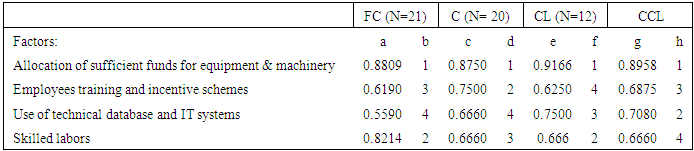

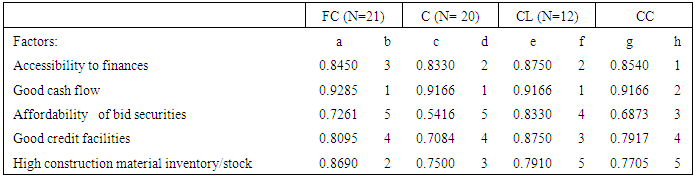

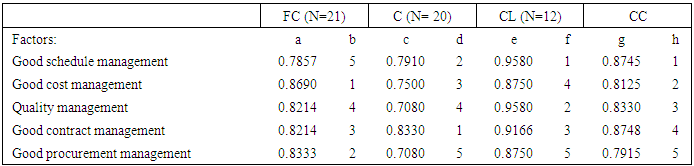

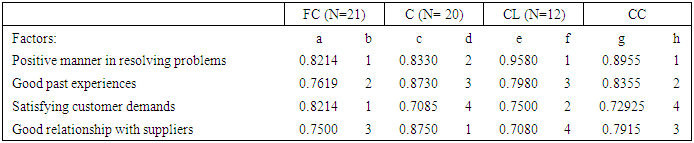

- Except for relationship resource that is externally sourced the results conform to the internal strength concept that is purported to significantly contribute to core competence [8, 6]). The results segment previous work that had investigated the role of core competencies in organizational performance [14] where skill integration, and knowledge where identified as key factors for core competence. The results also affirm the resource based view that competitive advantage is a product of heterogeneity of resources in an organization [6]. This is seen in the fact that the analysis has shown resource factors (see table 1-5) had scores above 75% implicating the respective resource/competence as highly significant. An illustrated relationship resource in Table 1 is noted to have 4 out of 6 resources of “highly significant” scores (above 75%). Table 2 analyzing equipment and plant showing 2 out of 4 resource factor scored, “highly significant”; table 3, financial capability with 4 out of 5 resource factors with “highly significant” scores; table 4 and table 5, depicting project management and reputation resources, all resources identified as “highly significant”. What can also be drawn from the data is the affirmation of existence of internal and external “dynamic competences” [31]. Dominance of internal dynamics as a contributing factor to core competence of the organizations has been portrayed by the study in that the top ranked resource factors are all except for one, inherently internal (table 6). Also the fact that ranking of clients and consultants who are virtually the customers has not significantly differed from contractors (table 6) is in support of Prahalad works [1] and [32]. These had acknowledged customer perceived value as also reflecting competence of the service being offered. Limitation and contribution of study:It is the authors opinion that the study could have been enriched if a comparative investigation would have been made to reflect status of the IRC variables of local contractors in Tanzania and assess “competitor differentiation” [1, 32] as criteria of core competence. In quest of explaining dominance in market share value of construction projects by foreign contractors, further studies could explore aspects of “extendibility” or Porters’ generic strategies of cost leadership, focus and service differentiation [33]. Despite the limitations the study has potential contribution to local contractors in Tanzania of how they could imitate foreign contractors through investing on the key competence variables identified by the study. The results of the study have also a potential of wider application for similar economies particularly developing countries.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML