-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2017; 6(1): 1-12

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20170601.01

Perspectives of the Causes of Variations in Public Building Projects in Tanzania

Yusuph B. Mhando1, Ramadhan S. Mlinga2, Henry M. Alinaitwe3

1Department of Construction Economics and Management, C/o Henry Alinaitwe, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

2Department of Structural and Construction Engineering, University of Dar‐es‐Salaam, Dar‐es‐Salaam, Tanzania

3College of Engineering, Design, Art and Technology, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

Correspondence to: Yusuph B. Mhando, Department of Construction Economics and Management, C/o Henry Alinaitwe, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Worldwide and particularly in developing countries there have been adverse effects on building projects as a result of constant variations in the course of implementing such projects. The objective of this study was to identify and analyse the major causes of variations in public building projects in Tanzania. This could help in monitoring the trends of variations and safeguarding the anticipated value for money in those building projects. Pertinent literature was reviewed coupled with structured questionnaires administered to architects, engineers, quantity surveyors and procurement officers to elicit individual’s perception with regard to factors of variations. The identified 25 factors of variations from literature were rated and ranked with regard to their importance and occurrence. Descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, factor analysis and t-test analysis were used to analyse data. Finding indicates the top four highly ranked factors of variations as change of plans or scope by clients, design discrepancies by consultants, misinterpretation of contract documents by the contractors and weather conditions. The agreement among respondents in rating and ranking the factors of variations was found to be considerable. Proper feasibility study of the project, sufficient time for design, inclusive design, and proper change control mechanism could help in reducing variations. Results from this study should help policy makers, construction practitioners, researchers and academicians to improve construction performance.

Keywords: Construction, Public building projects, Variations, Variation factors, Tanzania

Cite this paper: Yusuph B. Mhando, Ramadhan S. Mlinga, Henry M. Alinaitwe, Perspectives of the Causes of Variations in Public Building Projects in Tanzania, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 6 No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-12. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20170601.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Variations in construction projects continue to be a chronic problem worldwide and the situation is getting worse. The augmented occurrence of deviations from the original signed construction contracts is an indication that the construction sector has problems including variations that need to be addressed. In a generic sense, the word ‘variations’ in building contracts usually refers to a change in the works initiated by the architect, engineer, the employer or other factors as the case may be. It may involve the alteration of any kind or standard of materials to be used in the works [1]. However, it is observed that the occurrence of variations with their attached effects on construction projects is a global phenomenon [2, 3]. Moreover, the situation is dire in developing countries with the consequence of stagnated economic development [3]. It has been argued that in many countries particularly developing countries, the government is the largest construction client [4]. In this case, great concern has been expressed in recent years regarding the adverse impacts of variations in public building projects in Tanzania. Arguably, this is because such projects are implemented using meager public resources of which to the great extent come from tax payers’ money. Under normal circumstances one would expect the project to be completed within the initially anticipated cost, time and quality, but reality takes the opposite direction. Many cases of poor quality, late completion and cost overruns are being reported in many construction projects in Tanzania and some of these projects have not been successfully implemented as expected [5]. To date, several studies have been carried out on the causes and effects of variations in construction projects delivery [6]. However, most of these researches were too general with little attention on public building projects. In addition, these researches have inadequately investigated the major causes of variation in construction projects. These studies include [7] that contributed to theory and knowledge-based project change process; Ndihokubwayo and Haupt [2] found that variation orders were not realistically priced resulting in an increased construction costs. Others are [8] and [9] that managed to outline few causes of variations in Malaysia which fuel the need to look comparatively the experience of variations in other countries. This study attempts to uncover the causes of variations in building projects. Specifically this study was conducted to identify and evaluate the major causes of variations in public building projects in Tanzania. Pertinent literature was reviewed coupled with structured questionnaire administered to architects, engineers, quantity surveyors and procurement officers to obtain views with regard to factors of variations. Questionnaire survey has been used successfully in many studies such as [9] and [10] in generalizing results into other contexts. The statistical analysis was used to syntheses and analyse data. The major causes of variations were identified, evaluated and ranked according to their importance and occurrence. This study seeks to make a contribution towards finding solutions for minimising detrimental variations in public building projects. It is hoped that results from this study should help policy makers, construction practitioners, researchers and academicians to improve construction performance. The rest of the article is organised as follows: first, the literature on variations and their causes were reviewed. This is followed by a description of research methods and data analysis techniques used for the study. Results of the study are then discussed. The paper concludes with discussion of theoretical and managerial implications and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Concept of Variations

- Variation is defined as the change, modification, alteration, revision or amendment to the original intent of the contract and /or its works [11]. It may involve the alteration of kind or standard of any materials to be used in the works [1]. Moreover, it is an area of research in the construction industry that still needs to be researched, as it has received limited attention. To date, there is a very limited research work addressing the change management issues specifically within the construction project management context [12].There have been adverse effects on ongoing projects as a result of constant changes in the course of carrying out such projects worldwide [3]. Despite scarce resources, particularly in developing countries, building infrastructure for socio-economic development of the people is of high demand. However, construction projects implementation is the most critical resources consumer and visible phase of the project life cycle involving heavy financial disbursement. Major modification at any stage could have very serious financial repercussion [13]. Additionally, there have been major constraints and impediments challenging the implementation stage of project life cycle resulting into variation of the actual progress from the planned progress of project status.Variation of project scope, political factor, wrong estimate and faulty design may cause abandonment of a construction project, resulting in wastage of government resources [14]. Likewise, dubious payments by procurement entities to contactors due to non-contractual payments, repetition of work items, premature payment of preliminary items, unjustified variation orders, overpayments due to wrong assumptions, and paying for non-existing works are the relevant sources of variations in public building projects. It is therefore clear that construction work processes might have many unpredictable variations such that their minimization is necessary. Variations minimization will definitely result in saving time and money [15]. In fact, finished product in any industry requires satisfying a certain standard to provide customer satisfaction and the anticipated value for money [16]. Moreover, in construction almost all clients are interested in obtaining fully functional facilities completed in the anticipated time, cost, quality and scope. This is only possible if variations in all stages of building project development are properly identified, understood and managed. Thus, project management team must have knowledge, skills and abilities to deal with the day-to-day management challenges of changes [17].

2.2. Causes of Variations

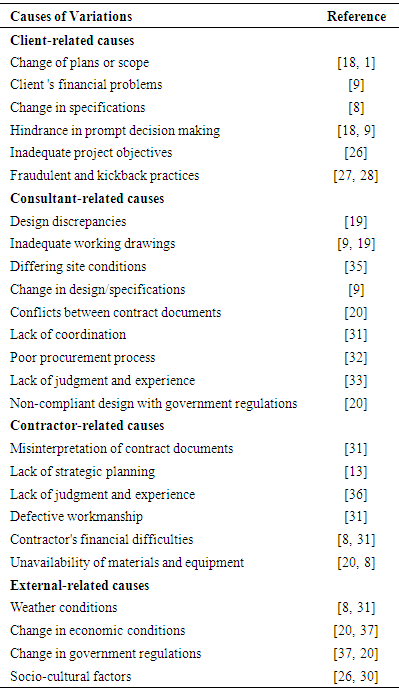

- The causes of variations in construction projects have been identified by many researchers [8, 9, 18-20]. Most construction projects especially in developing countries, usually suffer from cost and time overruns due to variations in project plans with the consequence of stagnated economic development [3, 13]. This implies that, for known reasons, numerous construction projects in developing countries particularly public construction projects are subjected to excessive variations than those in developed world. Ideally, a building would be designed so that variations would not be required in the construction stage. Certainly, for many clients this will be one of their main concerns, as the major instances of project cost and time overruns take place during construction phase. The nature of variations is usually defined by variation clauses in the conditions of contract [21]. However, variations involve not only changes in the work or matters relating to the work in accordance with the conditions of the contract but also changes in the working conditions. In fact, projects may get suspended or significantly amended before reaching the final stage as a result of variations. When variation often comes into account, it may increase the final contract sum. At that time, some items in original scope of work have to be deleted to manage variations within budget [6]. During the construction phase, some materials may be required in quantities more than stipulated in the variation clauses. This unfavourable condition is unacceptable in construction projects as many projects may come to an end with substantial positive variation amounts. However, most building projects are liable to variations that might be caused by change of mind in the part of the clients, consultants, contractors or any unforeseen scope of the project raised by one of the project participants. For instance, the engineers’ or architects’ review of the design may bring about changes to improve or optimize the design and the operation of the project [21]. Thus, causes of variations may originate from external and internal issues that may occur during the development phases of projects from basic design to construction [22, 23]. Variations originating from internal issues are those from the project organisation which involve clients, consultants and contractors. The study by [24] stipulates that each contracting practitioner (client, consultant and contractor) needs to understand own project performance issues. This implies that key players in a building project have a big role to play in ensuring that variations are controlled to generate good value for money. The study by [25] insist that variations may originate from three ways: (i) clients may change their minds about what they asked for before the work is complete; (ii) designers may not have finished all of the design and specification work before awarding the contract, and (iii) changes in legislation and other external factors may force changes upon the project team. However, there are many reasons that may cause the stakeholders to initiate variations during project administration [26].Change in specifications, change of plans or scope and noncompliance design with government regulations are the main causes of variations in construction projects in Singapore [18]. Client’s financial problem, unexpected site conditions due to improper site investigation, lack of feasibility study at the proposed site and unavailability of equipment are among the causes of variations in the Malaysian construction projects [8]. Furthermore, common factors of variations in the Malaysian construction projects are client’s financial problem and change in design or specifications [9]. Likewise, impediment in prompt decision making process, replacement of materials and procedures by the clients, design discrepancies and inadequate working drawings by consultants are the causes of variations in the Seychelles construction industry [19].Inadequate project objectives by client and socio-cultural factors are cited as the potential causes of variations in construction phases in Ghana [26]. Likewise, corrupt and fraudulent practices could be the potential sources of variations in the Tanzania construction industry [27]. However, to overcome the problem of corrupt and fraudulent practice some governments have developed and implemented procedural guidelines on procurement of services, goods and works [28]. Halwatura and Ranasinghe [20] found that non-compliant design with government regulations, lack of coordination between consultant and contractor, conflicts between contract documents, lack of materials and equipment are the significant causes of variations that adversely affect construction projects in Sri Lanka. Additionally, it is argued that lack of strategic planning by contractors plays a fundamental role in creating variations in construction projects [29, 30]. Lokhande and Ahmed [31] state that misinterpretation of contract documents, defective workmanship, financial difficulties by contractors, lack of proper coordination between the consultant and the contractor, weather conditions, change in government regulations and economic conditions are the potential causes of variations in the construction industry of Yemen. Poor procurement process is reported by [32] as the potential cause of variations in construction projects in Ghana. Moreover, lack of judgment and experience is the factor of variations in construction projects in Kenya [33]. From the syntheses of literature review, a total of 25 major factors that cause variations were identified and summarised in Table 1 with regard to their origin. Keane et al. [34] argue that the causes of variations could originate from client, consultant, contractor and non-party-related causes. The next section discusses research methods and data analysis techniques used for the study.

|

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

- Research design is an action plan for getting here to there [38]. ‘Here’ refers to initial set of questions to be answered and ‘there’ is some set of conclusion about the questions [38]. This study is designed to obtain views from architects, engineers, quantity surveyors and procurement officers with regard to the causes of variations in public building projects using a questionnaire survey.

3.2. Study Population

- The population of the study comprises of engineers registered by Engineers Registration Board (ERB), architects and quantity surveyors registered by Architects and Quantity Surveyors Registration Board (AQRB) and, procurement and supplies officers registered by Procurement and Supplies Professional and Technician Board (PSPTB) in Tanzania.

3.3. Questionnaire Design

- The questionnaire form was divided into two main sections. In section 1 of the questionnaire, the respondent was asked to fill in the space provided with the appropriate respondent’s general information. However, in section 2 of the questionnaire, the respondent was asked to rate causes of variations variables using five-point Likert scale viz-a-viz: strongly disagree = 1; disagree = 2; neutral = 3; agree = 4 and strongly agree = 5. Likert scale rating system has been used successfully by many researchers such as [9, 10, 39] in their studies.

3.4. Pilot Study

- A pilot study could help to refine data collection plans with respect to both the content of the data and procedure to be followed [38]. Thus, piloting the questionnaire with a small representative sample ensures the effectiveness of a questionnaire [40]. In this case, a judgment sample of 18 respondents with good spread of respondents’ characteristics was chosen for the preliminary testing of the questionnaire. Questionnaires were administered to architects, engineers, quantity surveyors and procurement officers contacted in person. Nevertheless, only 9 valid responses were received from respondents constituting 50 percent response which was considered adequate for validation. Based on the feedback, minor corrections were made to improve the format, layout, questions and the overall content of the questionnaire. Through this process, the questionnaire was validated and provided the authors with improvement opportunity prior to main survey.

3.5. Sampling Technique

- Sampling technique is a process of selecting a number of individuals or objects from a population to represent the entire population [41]. Given the wide distribution of public building projects and their heterogeneous nature around Tanzania, the purposive or judgment sampling method was adopted in this study. Patton argues that purposeful sampling is a technique widely used in research for the identification and selection of information-rich cases for the most effective use of limited resources [42].

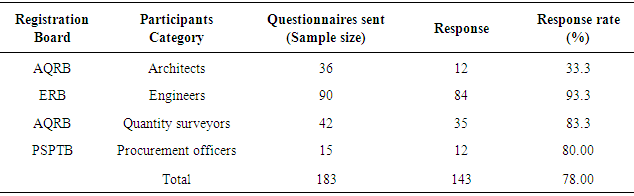

3.6. Sample Size and Selection

- The primary data for this study were collected from multiple construction professionals around Tanzania using a questionnaire survey. A total of 183 questionnaires were purposively administered to 36 architects, 90 engineers, 42 quantity surveyors and 15 procurement officers contacted in person to get individual’s perception. Telephone call and short message system (SMS) reminders were used to follow up on the responses. Table 2 shows that 143 valid responses were received, constituting a response rate of 78% which was considered adequate for data analysis.

|

3.7. Data Analysis

- The analysis of the data was carried out with the help of statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 17. Data were carefully analysed statistically using descriptive statistics, frequencies, Cronbach’s alpha reliability test, factor analysis and t-test analysis to draw inferences.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Reliability Testing

- Reliability test was carried out to determine whether the questionnaire was capable of yielding similar scores if the respondents have used it twice. The test was conducted using SPSS version 17.0. The determined Cronbach’s alpha coefficient value for the rated 25 items of the questionnaire was 0.857. This value indicates that the questionnaire items form a scale that has reasonable internal consistency reliability. Impliedly, the survey instrument used was reliable and acceptable and that an agreement exists between construction industry practitioners in ranking the factors of variations accordingly. Reynolds and Santos specify that an alpha greater than 0.7 implies the instrument is acceptable [43].

4.2. Respondents’ Characteristics

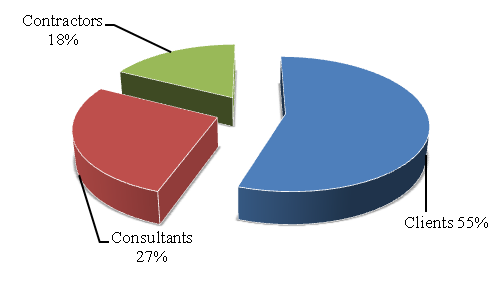

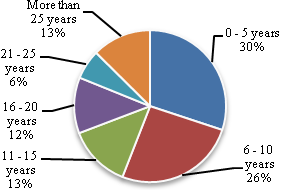

- Respondents were categorised in terms of their parties and work experience as shown in Figures 1 and 2 respectively. Result indicates that majority of the respondents (55%) were from clients. This has made this study worthwhile because the study was on public buildings projects. The determined average of 15 years of professional work experience of respondents was considered suitable such that the responses given by those professionals were considered reliable and trustworthy. However, most participants have been in the construction industry for the period of 1-5years i.e. 30% of the 143 participants. This is still worthwhile for this study because 1-5years experience implies that most participants might have been involved in construction projects not less than three years.

| Figure 1. Respondents by Parties |

| Figure 2. Respondents by Work Experiences |

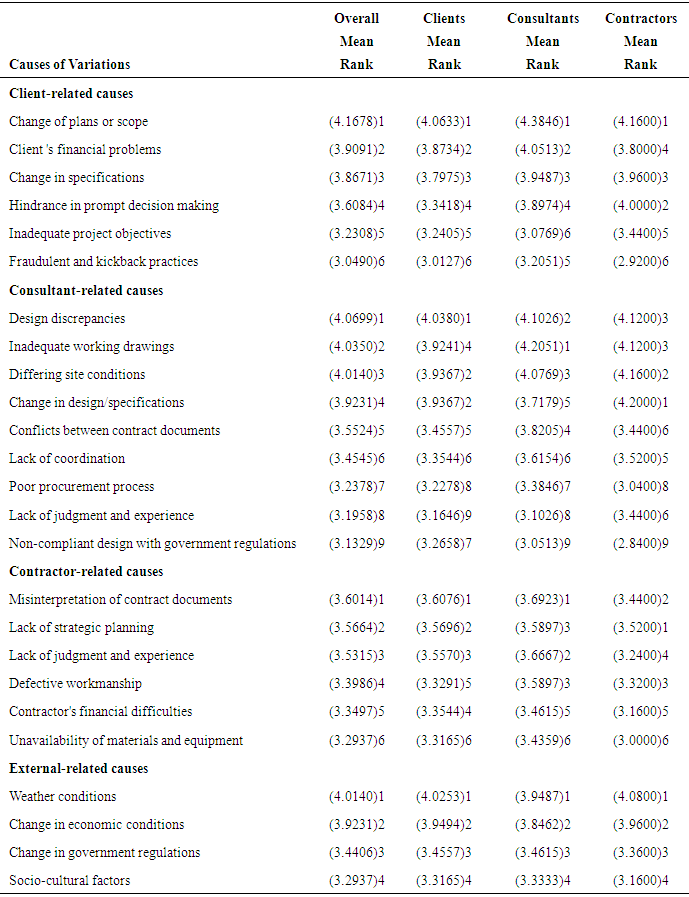

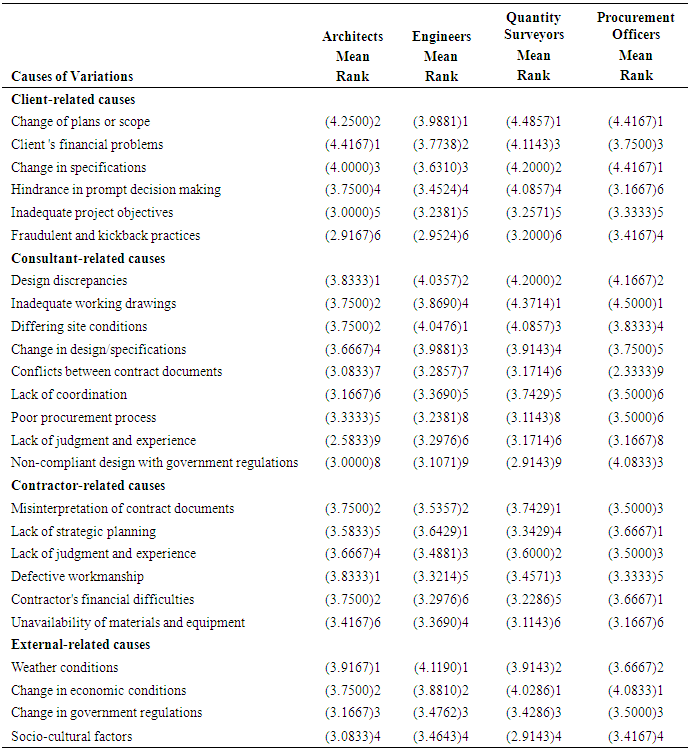

4.3. Causes of Variations

- Tables 3 and 4 respectively present results of the ranking of variation factors from the perspectives of the parties and the professionals. For clarity, the major causes of variations were categorised as client-related; consultant-related; contractor-related and external factors-related causes of variations as discussed here under.

|

|

4.3.1. Clients-Related Causes

- From the group of client related causes of variations, the result indicates that change of plans or scope by clients was ranked first as the most predominant cause of variations from all viewpoints, except architects ranked it second. Impliedly, there was no much interaction between the design team and client to ensure that client’s requirements are clarified and communicated effectively to reduce non-compliance with client’s requirements. Studies by [3] and [19] affirm that change of plans or scope by clients is a factor that contributes mostly to the causes of variations in the construction of Iran and Seychelles respectively. Furthermore, the highest number of variations and omissions that occur in construction projects was contributed by the clients [18]. Ideally, clients should exhaust early all the preferable inputs at the design stage to avoid new inputs during construction stage, thus avoiding variations. In this case, quantity surveyors (mean = 4.4857) were more concerned with the change of plans or scope by the client. This is because somehow always affected by variations as they are responsible to quantify variation quantities and the associated costs. Client’s financial problem was ranked second from the overall, engineers, clients and consultants viewpoints. This may imply that, due to various reasons most clients fail to release funds on time with the consequence of cost and time overruns in those projects. Client’s financial problem is the common factor of variations in the Malaysian construction projects [9]. The rest ranked factors were also identified in other countries such as change in specifications [8] in Malaysia, hindrance in prompt decision making [19] in the Seychelles construction industry and inadequate project objectives [26] in Ghana. However, contractors, architects and engineers have rated fraudulent and kickback practices as the lowest cause of variations since it has mean value less than 3. Most probably, this is because Tanzania government through Public Procurement Act (PPA) of 2004 prohibits corrupt and fraudulent practices by all parties of the project [27]. In fact, fraudulent and kickback practices are the elements of “corrupt practice” which allows the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting anything of value to influence the action of a public officer in the procurement process or contract execution. This has resulted into many issues such as dubious payments by procurement entities to contactors due to non-contractual payments and unjustified variation orders.

4.3.2. Consultants-Related Causes

- From the causes of variations that were initiated by the consultant, design discrepancies were ranked first from the overall, architects and clients viewpoints. However, from viewpoints of engineers, quantity surveyors, procurement officers and consultants were ranked second, except contractors placed it in the third position. Though quantity surveyors ranked it second (mean = 4.2000), they seem to be more anxious on it as they are responsible to quantify variations resulting from design discrepancies. The inconsistency in design can be caused by various factors including the inability of the design team to accommodate the project requirements from the client and other stakeholders. It is asserted by [44] that conceptualizing design and construction process from recognition of a project need to the operation stage ensures informed decision-making at the front end of design and construction development process. Inadequate working drawings were ranked second from the overall and architects viewpoints. However, were ranked first from the viewpoints of consultants, quantity surveyors and procurement officers. This ranking somehow is in agreement with the views of [19] that ranked inadequate working drawings in the first position. Ndihokubwayo and Haupt [2] claim that 18% out of 47% of the variations related to consultants was contributed by lack of detailed drawings. In fact, lack of detailed drawings can be caused by several factors including consultant’s lack of judgement and experience in design. The rest ranked factors as identified in other countries were differing site conditions [8] in Malaysia; change in specifications [18] in Singapore; non-compliant design with government regulations, lack of coordination and conflicts between contract documents [20] in Sri Lanka; poor procurement process [32] in Ghana and lack of judgment and experience [33] in Kenya. Basically, respondents have agreed that all factors with means greater than 3 were the significant causes of variations related to consultants.

4.3.3. Contractors-Related Causes

- In this section of contractors’ related causes of variations, result shows that misinterpretation of contract documents was ranked first from the overall, clients, consultants and quantity surveyors viewpoints. However, it was ranked second from the viewpoints of contractors, architects and engineers, except procurement officers ranked it in the third position. Interestingly, architects (mean = 3.7500) are more concerned with the problem of misinterpretation of contract documents. This may imply that architects or consultants have big role to play in preparing unambiguous contract documents for the projects. In order to convey a complete concept of the project design, the working drawings must be clear and concise [26]. A delay due to misunderstanding in one of the contracts would cause disruptions in other contracts schedule [31]. Other ranked factors which also identified in other parts of the world were lack of strategic planning [29] in Canada; lack of judgment and experience [33] in Kenya; unavailability of materials and equipment [20] in Sri Lanka; defective workmanship and financial difficulties [31] in Yemen. Overall, unavailability of materials and equipment were considered the lowest cause of variations. However, unavailability of materials and equipment could be caused by price escalation during construction phase which may require proper contingency plan to ensure the availability of adequate resources for the project.

4.3.4. External-Related Causes

- This section discusses analysis results of external related causes of variations. In this case, weather conditions were considered as the major cause of variations and ranked first from the overall, clients, consultants, contractors, architects and engineers viewpoints. However, quantity surveyors and procurement officers ranked it second. Impliedly, the contractor may need to adjust the construction schedule accordingly due to varying weather conditions. This may cause time variation that may adversely affect the project progress, leading to delays. Changing weather conditions such as rain, snow, wind, and adverse temperature conditions have serious impacts on productivity resulting into delays in construction and variations in the schedule [31]. Furthermore, weather changes are the cause of variations that are not directly related to the project participants [8]. However, engineers (mean = 4.1190) and contractors (mean = 4.0800) seem to be more vigilant with weather conditions. Ideally, this is because engineers and contractors are responsible for the fieldwork to realize projects objectives. Change in economic conditions and change in government regulations were ranked second and third respectively. These causes of variations were also observed by [20] in Sri Lanka. Overall, socio-cultural factors were considered the lowest cause of variations and ranked fourth. The study by [26] reveals that in the Ghanaian construction industry socio-cultural factors are one of the causes of variation with less impact. However, most construction industries in developing countries are characterized by both local and foreign firms where by professionals with different socio-cultural backgrounds work together and encounter a number of problems due to different perceptions and language barriers. This situation may cause lack of coordination and communication between professionals in the construction project working environment, leading to reworks and delays.

|

4.4. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

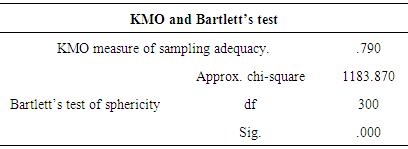

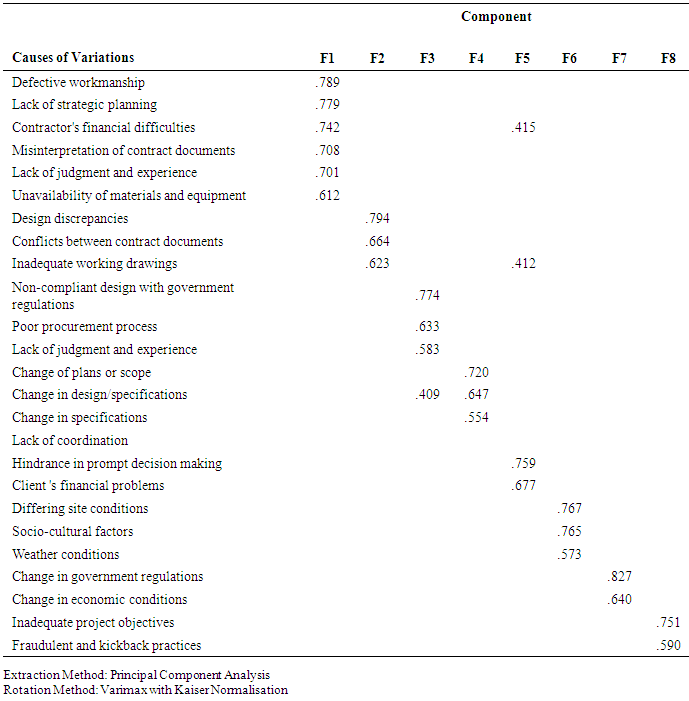

- The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was carried out by using Varimax orthogonal rotation criteria to explore and understand the underlying relationships within the 25 variables used in this study. PCA has been used successfully by many researchers such as [43] and [45] in their studies. It is argued that a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value close to 1 indicates that the patterns of correlations are relatively compact and so factor analysis should yield distinct and reliable factors. It also specify that values between 0.00 and 0.49 don’t factor, values between 0.5 and 0.7 are mediocre, values between 0.7 and 0.8 are good, values between 0.8 and 0.9 are great and values above 0.9 are superb. From Table 5, the determined KMO value was 0.79, which falls into the range of being good. Further, the determined approximate Chi-square in the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was 1183.870 and the significance was 0.000. These values provide confidence that the conducted factor analysis was appropriate and the variables were correlated highly enough to provide a reasonable basis for factor analysis.Table 6 indicates the extracted eight components whose Eugenie values were over 1.000. They accounted for 67.439% of the common variance shared by the 25 variables. The extracted eight components from factor analysis were outlined as performance deficiencies (F1), design challenges (F2), guiding rules (F3), incomplete and unclear specifications (F4), decision making and financial challenges (F5), unpredictable issues (F6), government intervention (F7) and, project scope and ethical issues (F8). Apparently, these issues were of great concern to participants in evaluating the causes of variations in building projects.

|

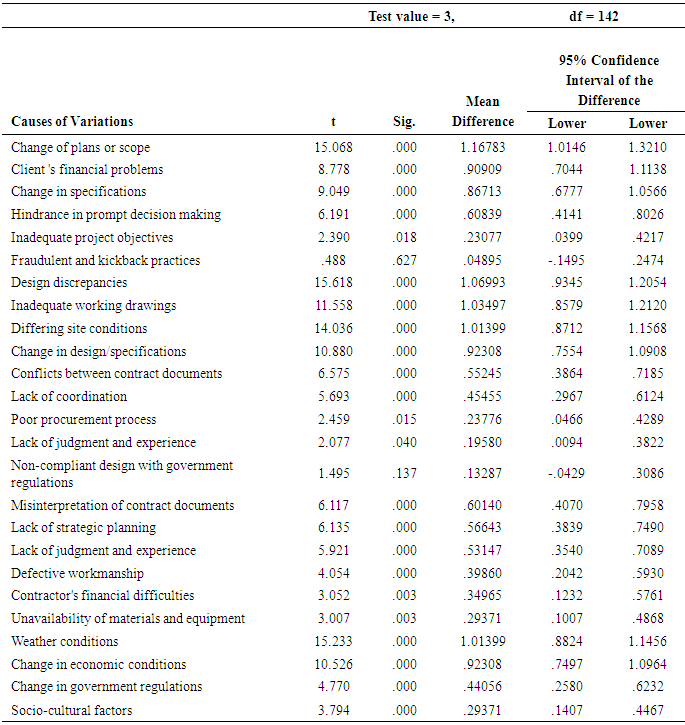

4.5. One-Sample T-Test Analysis

- One-sample t-test analysis was employed to test for significance in ranking the factors of variations. The test value was set as 3 because the rating scale ranges from 1 to 5 with 3 being a neutral position. Results in Table 7 show that the analysed 25 factors of variations demonstrate significant values less than 0.05. Impliedly, the difference in means is statistically significant at the 0.05 confidence level. However, non-compliance design with government regulations and, fraudulent and kickback practices exhibited higher values than 0.05. This suggests that, the difference in means is statistically not significant at the 0.05 confidence level. Also the 95% interval of difference (ρ = 0.05) shows that all rated factors have both the upper and lower limits either below or above zero meaning that they are practically significant. Therefore, it can be inferred that the ratings of variation variables were significant.

|

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Finding of this study shows that building projects suffered for the problem of variations. Change of plans or scope by client was the most predominant cause of variations and was ranked first in the category of clients. Evidently, design discrepancies in the category of consultants were ranked first as the potential cause of variations. Misinterpretation of contract documents in the category of contractors was ranked first as the significant factor that contributes to variations. Relatively, weather conditions were ranked first as the most causal factor that contributes to variations. The t-test result indicates that the ratings of variables were significant as discussed in sub-section 4.5. Thus, it is optimistic that the finding of this study should inform the professionals, policy makers, academicians and researchers in managing and improving construction performance of building projects. Team work spirit among project parties is the key ingredient in a successful project. Additionally, proper feasibility study of the project, sufficient time for design, inclusive design, and proper change control mechanisms could help in reducing variations in public building projects.

6. Research Limitations

- Although this research work has generated important findings in the field of construction management, its design is not without flaws. Based on the limitation of not being able to sample more than 90 engineers, 42 quantity surveyors, 36 architects and 15 procurement officers, future research should employ a large number of respondents. In addition to quantitative technique, a qualitative study of the causes of variations should be performed. This could help to maximize the strengths and minimize the limitations of each technique [40]. Moreover, discussion of other relevant causes of variations in construction projects is beyond the scope of this study.

7. Contributions

- Results of this study should help to monitor the trends of detrimental variations in public building projects. These results also form a baseline for future researches in the area of construction in the context of Tanzania. Moreover, these study findings can form a base for comparison with other construction industries from various parts of the world to improve construction performance. It is therefore optimistic that the study finding could provide useful insights in engendering managerial efficiencies and effectiveness towards successfully improvement of construction performance.

8. Future Research

- The findings of this study could be used as input for future studies. Specifically, further research could focus on developing a generic conceptual process flow model for effective mitigation of variations in public building projects. The model as a tool should help policy makers, academicians and professionals of the construction industry to curb construction variations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors acknowledge with thanks the Arusha Technical College (ATC) of Tanzania for financial support and Makerere University (MAK) of Kampala Uganda for providing other required necessary resources that made this study possible. Grateful to Tanzania government agencies, institutions, the consultants, the contractors and individuals for providing comprehensive and important information, and genuine cooperation which resulted into the easier availability of the data needed for the research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML