-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2016; 5(1): 11-24

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20160501.02

An Index to Assess Project Management Competencies in Managing Design Changes

Mahsa Taghi Zadeh1, Reza Dehghan2, Janaka Y. Ruwanpura1, George Jergeas1

1Department of Civil Engineering, Schulich School of Engineering, University of Calgary, Canada

2Sharif University of Technology, Tehran, Iran

Correspondence to: Mahsa Taghi Zadeh, Department of Civil Engineering, Schulich School of Engineering, University of Calgary, Canada.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Design changes, whether voluntary or imposed, are common and inevitable in oil and gas projects. These changes are significant sources of cost growth and time delays in projects. As a result, identification of the factors contributing to design changes concerns a number of researchers and professionals in the industry. One of the main factors is project management competency, which significantly contributes when dealing with design changes. This study aims to develop an index for assessing the competency level of a project management team through identifying and rating the main skills and characteristics attributed to team members. The data was acquired through a questionnaire survey along with a series of interviews and brainstorming sessions with practitioners in the industry. The Project Management Competency Index provides a common forum for all project participants to assess and rate the competencies of a project management team. Knowing the composition of a PM team, the team members' background and work experience, and their skills and characteristics constitutes an important step in evaluating and monitoring the performance of a PM team handling design changes at different points during project execution. This is crucial for selection of an effective team able to control and manage all issues related to project design changes. The PMCI, when combined with other key factors, can also greatly improve the predictability of design changes. The result of this study forms part of the authors' ongoing research which focuses on developing a predictive model for pattern recognition of the impact of design changes on project performance.

Keywords: Project management, Skills and characteristics, Design changes, Competency index, Predictability

Cite this paper: Mahsa Taghi Zadeh, Reza Dehghan, Janaka Y. Ruwanpura, George Jergeas, An Index to Assess Project Management Competencies in Managing Design Changes, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 5 No. 1, 2016, pp. 11-24. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20160501.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The oil and gas business is one of the most important and largest industries in the world that affects all aspects of our lives. The global demand for energy is met to a large degree by this industry. Despite the large economic contribution of the industry, the performance of major projects has not been meeting expectations, particularly with respect to cost and schedule targets.In recent years, it has come to light that a major factor contributing to the incidence of cost overruns and time delays in projects is rework, which typically manifests itself in the form of changes and errors. Design-induced rework has been reported to account for approximately 70% of the total amount of rework experienced in construction and engineering projects [1, 2]. The inherent inter-dependency of engineering works, the extensive flow of information, and the interconnected nature of design and construction activities in oil and gas projects may result in a wide spectrum of design changes throughout project execution. These changes include any additions, omissions or adjustments to project design requirements, drawings, and specifications that may occur due to errors and omissions, scope addition and deletion, and design improvement. According to the study performed by Sun and Meng [3] on the causes and effects of changes in construction projects, the success of a project, to a large extent, is determined by the ability of the project team to manage the inevitable changes throughout project life cycle.A survey conducted by Hwang and Low (2011), assessing the status of change management implementation in the Singapore construction industry, showed out of a total of 384 projects, only 121 projects (32%) implemented change management, indicating that the implementation status of change management is moderately low. Among possible reasons for this low implementation status were unfamiliarity of professionals with the process of change management and lack of experienced resources [4]. Given the complex nature of oil and gas projects, particularly in a competitive work environment, the competencies of project management personnel are seen as having a major role in overcoming the problems associated with design changes and errors. The project management team must have a wide variety of knowledge, skills, and abilities to deal with the day-to-day management challenges of changes. Project managers’ roles and performance guidelines are well established in the literature, in academia and by professional bodies, such as the Project Management Institute [5, 6], the International Project Management Association [7], the Global Alliance for Project Management Standards [8], and the Australian Institute of Project Management [9]. The project management standards published by professional institutes have been widely used to certify project manager's competence with the assumption that management practices are context-independent and universal [10, 11].Despite a considerable amount of research on the general subject of project changes and project management competency, very little is known about dealing with human-related factors contributing to project change management and in particular quantifying the competency level of a project management team in controlling and managing design changes.This study aims to provide an insight into the essential elements of project management competency and to develop an index quantitatively assessing the competency level of project management team members who are involved in the process of design change evaluation and implementation. The paper starts with a brief overview of the literature, followed by an explanation of the research methodology and the data analysis of a survey conducted in the oil industry to establish the competency index. The results are then presented and discussed. The last part of the study addresses the implication of the findings for development of the project management competency index.

2. Background / Literature Review

- The literature review is divided into two parts: the first part reflects on the literature describing competency and the second part reviews the literature on professional competency in the field of project management, with consideration of managing project changes.

2.1. Definition of Competency

- The subject of competency has been at forefront of discussions among researchers for over two decades [8, 11-17]. Different definitions and theories have been proposed by various academic and industrial research groups purporting to explain “competency”. Woodruffe (1991) defines competency as a person-related concept that refers to the dimensions of behaviour underlying competent performance [18]. According to Parry (1998), competency refers to a cluster of related knowledge, attitudes, and skills that affects a major part of one's job; that correlates with performance on the job; that can be measured against well-accepted standards; and that can be improved via training and development [19]. The term "competency" has also been defined in the literature as the "underlying characteristics of an individual causally related to criterion-referenced effective and/or superior performance in a job or situation" [13, 20], and the “clusters of skills, knowledge, abilities, and behaviours required for success” [21]. In this study, we have taken a broad view of competency, as have others: skills, attitudes, knowledge, and personal characteristics that can be improved with experience, education and training.

2.2. Competency in Project Management

- Professional competency in project management has been addressed by a number of research studies which are primarily based on the opinions of project management practitioners. Some studies have highlighted the significance of PM skills and characteristics in project success [16, 22-25], while others have assessed PM competencies across cultures and industries [17, 26-30]. Several of the studies conducted on project managers' competencies have focused more specifically on the importance of human skills [11, 31-38].In the early 1980s, Boyatzis (1982) applied the concept of competency to managers and defined competency as "an underlying characteristic of a person, including motives, traits, skills, aspects of one's self-image or social role, or a body of knowledge which he or she uses" [39]. Kliem and Ludin (1992) indicated that successful project managers should recognize the importance of managing people in projects by applying good interpersonal skills [40]. Crawford (2005) categorized project managers’ competencies into three main categories, namely: input competencies (referring to a person’s job-related knowledge and skills), personal competencies (referring to a person’s core attributes and capabilities) and output competencies (referring to a person’s demonstrable performance) [13].One of the early attempts to link project managers' skills and characteristics to project success was conducted by Todryk [31]. This study showed that a well-trained project manager can create an effective team—a key factor in the success of a project. Edum-Fotwe and McCaffer (2000) identified the general knowledge and skill elements perceived as essential for developing project management competency through a survey of project managers in the construction industry [26]. The results emphasized the important role of experience for achieving, maintaining and renewing skills and competencies in construction project management. A study by Starkweather and Stevenson [16] examined the relationship between project management certification and established project management core competencies in the IT industry. This analysis showed that there was no difference in project success rates between PMP®-certified project managers and uncertified project managers. A number of studies have attempted to develop different competency models in various industries. The dominant works are those by [26, 27, 41, 42]. Brière et al. (2014) identified competencies of international development project managers and how these competencies are used in projects [17]. The findings of their study highlighted the importance given by managers to the competencies they must develop based on the environment where the projects are carried out. The personal competencies required to manage organizational changes have been addressed by Crawford and Nahmias [15]. The main change management competencies summarized by their study are: leadership, stakeholder management, team development, planning, communication, decision making, cultural awareness, and problem solving. A study by Hwang and Ng [42] discovered challenges faced by project managers who execute green construction projects and determined the essential knowledge areas and skills required to be a competent project manager. The results revealed that the most important knowledge areas required to mitigate the challenges were schedule and cost management, stakeholder management, communication management, and human resources management. Also, the most critical skills highlighted by this study included analytical, decision-making, team working, delegation, and problem-solving skills. Studies on project managers’ competencies have also addressed the importance of behavioral and social skills of project managers in dealing with project related issues. Dulaimi and Langford (1999) investigated the behavioral competencies of project managers in the construction industry, identifying an appropriate leadership profile for project managers [32]. El-Sabaa (2001) revealed that the human skills of project managers have the greatest influence on project management practices [43]. Characteristics included in this category of skills were communication, mobilization, coping with situations, delegation, political sensitivity, high-self esteem and enthusiasm. Similarly, a recent study conducted by Stevenson and Starkweather (2010) investigated the human characteristics necessary to achieve project success across US industries [28]. The results identified six critical core competences: leadership, verbal and written skills, the ability to communicate at multiple levels, attitude, and the ability to deal with ambiguity and change that were indicative of important skills and characteristics of successful project managers. Skulmoski and Hartman (2009) focused on the soft competencies of project managers in different phases of IT projects in Alberta, Canada [35]. The findings of their study showed that as the required tasks change in each phase, so do the required competencies. Other notable research addressing behavioral aspects of PM competency includes [13, 33, 34, 44-47].In addition to academic research, project management competency has also been explored by various professional associations and institutes. Main publications include the National Competency Standards for Project Management [9], the IPMA Competence Baseline [7], the Project Manager Competency Development Framework [5], and the Project Management body of Knowledge Guide (PMBOK® Guide) [6]. These standards have been widely used to certify project managers' competence. IPMA's competency model classifies project manager's competencies into three different groups: technical competency (describing the functional elements), behavioural competency (describing the personal elements), and contextual competency (describing the elements related to the context of project) [7]. These competency standards which are generic in nature assist in improving the management qualifications of experienced and new professionals.

2.3. Research Rationale and Motivation

- Despite a considerable amount of research on the subject of project management competency and the skills and characteristics required for project managers in different industries, very little is known about investigating the role of human-related factors in project change administration and management and, in particular, quantifying the competency level of a project management team in controlling and managing design changes in oil and gas projects.Owing to the complexity of oil industry projects and the role of project management professionals in overcoming the problems associated with design changes, there appears to be a need for more research into evaluating and quantifying project management competencies.Building on the foundation of existing research works, this study aims to bridge the knowledge gap by determining the significance of the main components of PM competency and providing insight into how the competency level of a project management team dealing with project changes is quantified taking into consideration the differences among team members.

3. Research Purpose and Method

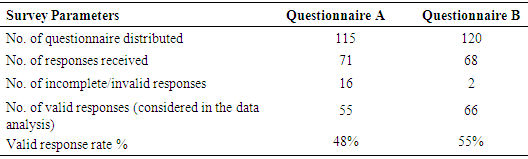

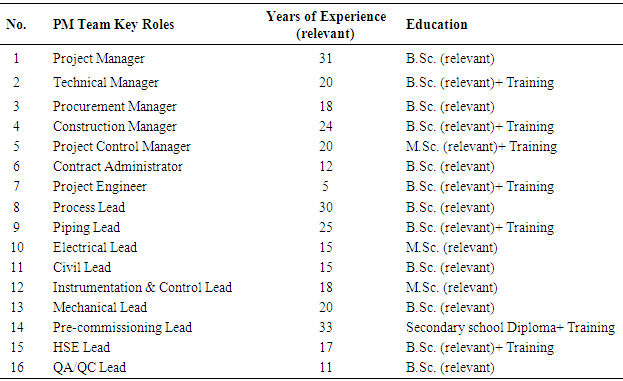

- The main objective of this study is to present a quantifiable index for measuring the competency level of a project management team administering and managing design changes in oil industry projects. The study was conducted through the following three stages: (a) determining the relative importance of the key elements of PM team competency, (b) identifying and determining the significance level of each PM team role in dealing with design changes, and (c) developing an appropriate index to measure the competency level of a project management team (the Project Management Competency Index or PMCI).At the first stage, the key elements of project management competency were identified through a comprehensive literature review, the authors’ own experience and face-to-face interviews conducted with six PM professionals in the oil industry. The results were then analyzed qualitatively and grouped into three major categories through a group discussion at a workshop consisting of five project management experts. The relative importance of the main categories of PM competency was determined by administering a questionnaire survey (Questionnaire A) to the industry practitioners. At the second stage, an initial list of different roles and designations in a project management team was derived from the authors' experience in the industry and refined throughout the course of interviews with an expert group. A questionnaire survey (Questionnaire B) was then conducted to obtain the viewpoints of the experts on the significance of various roles in a project management team in handling design changes. At the final stage, using the findings of the earlier stages of the study and through two brainstorming sessions of a focus group of PM professionals (three participants in each session), the project management competency index was developed.Web-based Questionnaire SurveysA web-based administration tool, Survey Monkey, was used for survey design and hosting of the study. Two sets of questionnaires—Questionnaire A, which was structured to elicit the relative importance of main elements of PM competencies, and Questionnaire B, which elicited the relative importance of different roles and designations attributed to a project management team—were developed by employing the outcome of the interviews and the data obtained from the literature survey. The questionnaires were distributed to a total of 115 and 120 professionals, respectively, representing a wide range of professions dealing with project changes in Alberta's oil industry. In the first stage, participants were invited to score their perception of importance for the main elements of PM competencies on a five-point Likert scale (1 for "not important at all", through "slightly important", "moderately important", and "important" to 5 for "very important"). From 115 questionnaires (Questionnaire A) administered in the industry, a total of 71 questionnaires were returned, of which only 55 were properly completed, representing a 48% response rate.In the second stage, participants rated the level of significance of each role/designation in a PM team considering their level of contribution to design change evaluation and management practices. A ten-point Likert scale (with 1 indicating no contribution and 10 indicating very high contribution) was used to score the different roles. For Questionnaire B, from 120 questionnaires distributed, a total of 68 were returned of which 66 were completed. This represents a response rate of 57%, which was only achieved after several efforts made via follow-up emails and letters. Table 1 provides summary statistics of the questionnaire surveys.

|

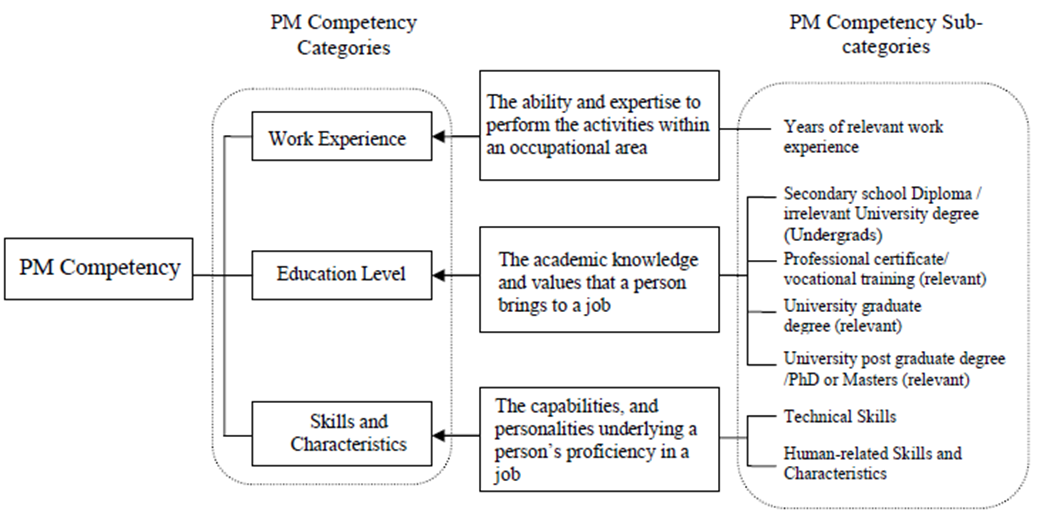

4. Key Elements of Project Management Competency

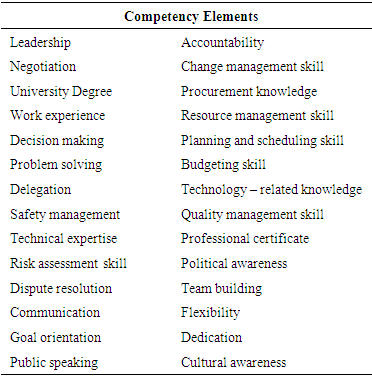

- Managing a large-scale project is a complex task requiring several knowledge areas, a variety of technical and management skills and a combination of personal and behavioral competencies. A study performed by Fox and Miller (2006) summed up the challenges in managing projects [48]: "Managing [a large complex project] is more than a science; it is a continually evolving art".This study has identified and categorized the key elements of project management competency. The list of elements is presented in Table 2.These competencies were tuned up and categorized based on the outcomes of a focus group discussion consisting of five project management experts experienced in oil industry projects in Alberta. Figure 1 shows the three main categories: work experience, education level, and skills and characteristics.

|

| Figure 1. Categories of project management competency elements |

4.1. Work Experience

- Professional competency in project management is attained by the combination of knowledge acquired during training, and skills developed through experience [26]. Singh and Hofmann (2012) shared experience gained in planning and implementing a competency development program designed for project managers in global R&D projects [49]. The results revealed that the experience obtained through managing projects cannot be acquired through any other means. Work experience contributes significantly to the development of skills and expertise of a project management team. The efficacy of project management practices will vary depending on the experience of project management team members. Hanna et al. (1999 b) investigated the effects of management experience in handling change orders, and showed that the more experience a project manager has in the field of the project, the more that PM is able to reduce inefficiency due to change orders [50].

4.2. Level of Education

- Education complements the experience of project management practitioners in the workplace. Berggren and Söderlund (2008) demonstrated the need to create a training environment fusing the knowledge of practitioners with academics [51]. Project management encompasses a wide range of roles and responsibilities, as reflected in educational programs. Many colleges and universities offer courses in engineering alongside business administration programs covering techniques and concepts of project management. Increasingly, degrees are offered at the master's or doctoral levels. There are also a number of institutions providing project management training courses and professional certificates. Founded in 1965, the International Project Management Association (IPMA), representing a federation of more than fifty national project management associations, provides various certification programs for the work of project management professionals. The other significant institution is the Project Management Institute (PMI), one of the largest not-for-profit associations, with credential holders in more than 185 countries. Research about project management education underlines the need for training focused on the development of project management soft skills along with the required technical knowledge. Pant and Baroudi (2008) proposed a new way of thinking to broaden existing approaches in project management education by incorporating greater human skills into educational programs [45]. Recent studies have also investigated the improvement of project management training and education using real life components [52-54]. Researchers believe academic and training programs at universities and professional institutions need to assist trainees studying project management in the context of its application. Notably, Ramazani and Jergeas (2015) identified three main areas that should be considered by educational institutions in training project managers: 1) developing critical thinking to deal with complexity, 2) developing softer parameters of managing projects, and 3) preparing project managers to be engaged in real projects [54].

4.3. Skills and Characteristics

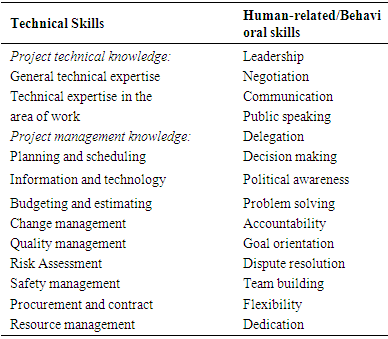

- A mixture of skills and characteristics is required for a project management team to manage a project successfully. Mantel et al. (2001) categorized the skills required for project managers into six areas: communication, organizational, team building, leadership, coping, and technological skills [55]. In the current research, to evaluate the competency level of a project management team, the main skills and behavioural personalities of project managers have been divided into technical and human-related skills.Technical SkillsEach member of a project management team must have competent technical skills in the relevant field of expertise to implement and integrate all aspects of the project, as well as an adequate knowledge and proficiency at using project management tools and techniques. Although project managers do not need to be experts in the technical areas of the project, basic technical knowledge is a great asset for project managers. The more technical expertise project managers have in the field of a project, the greater their effectiveness in managing the work.Projects are becoming more complex, and project managers need to spend more time on management skills. The main skills essential to successful project management include planning and scheduling, budgeting and cost control, estimation, quality control, and construction management. These skills are necessary to assess project risks and to make trade-offs of cost, schedule, time, and quality.Human-related Skills and CharacteristicsThe importance of human skills in managing projects has been emphasized in a number of studies [22, 26, 43, 56- 57]. According to Borman and Motowidlo [58], behavioural competencies can be grouped into two main categories: task performance behaviours (contributing to the technical and managerial functions, such as planning, coordinating, delegating, and so forth) and contextual performance behaviours (contributing to the organizational, social and psychological environment, such as conscientiousness, commitment, initiative, or dedication).Aitken and Crawford (2008) studied the personality characteristics and behavioural competencies of project managers working in fourteen countries [14]. The study revealed a group of behavioural characteristics associated with successful project managers, including: deciding and initiating action, delivering results and meeting customer expectations, leading and supervising, and persuading and influencing. The interpersonal and behavioural skills most critical for effective performance of a project manager include leadership, team building, communication, problem solving, negotiation, decision making, public speaking and delegation. These attributes signify the ability of a project manager to build a cooperative working environment in which all project participants interact.

5. Data Analysis and Discussion

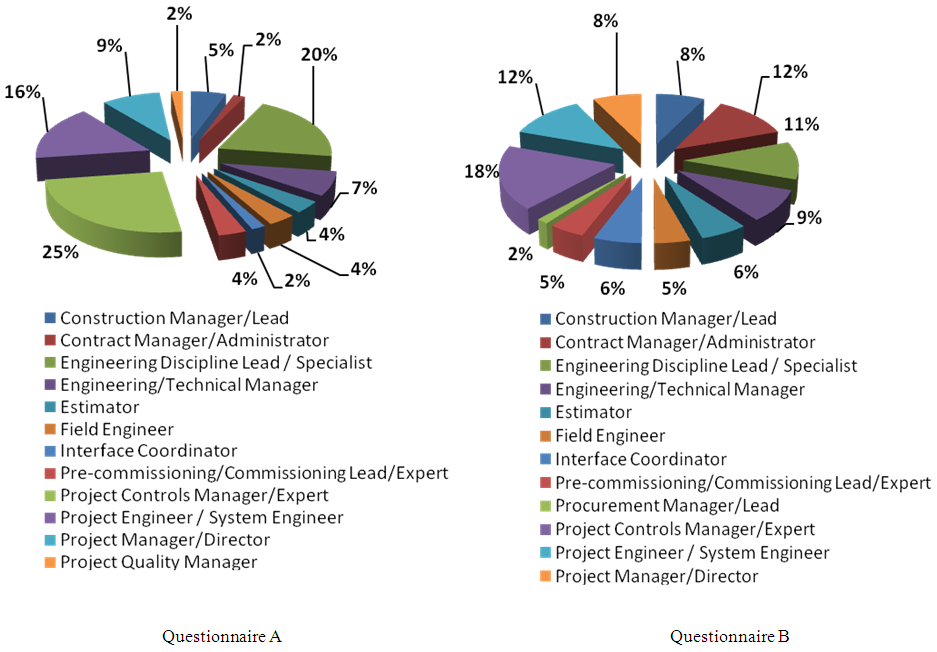

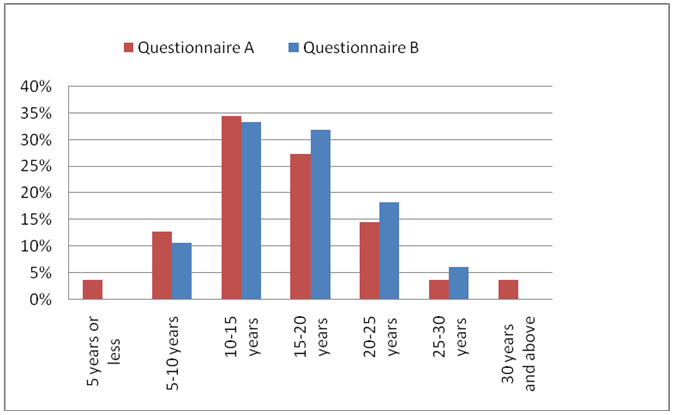

- Demographic analysis of questionnaire surveys was conducted to provide a general background of participants in the surveys. Figure 2 and Figure 3 depict the designation and the years of experience demographics of the respondents, respectively. A high proportion of respondents (70% in survey A and 60% in Survey B) were from disciplines directly involved in design change administration (i.e. project management and design engineering teams). The surveys also revealed that the majority of respondents possessed relevant experience of between 10 to 20 years in oil and gas projects. This suggests most of the respondents were suited to comment on the issues dealt with in the survey.

| Figure 2. Respondents’ positions demographics |

| Figure 3. Respondents’ Work Experience Demographics |

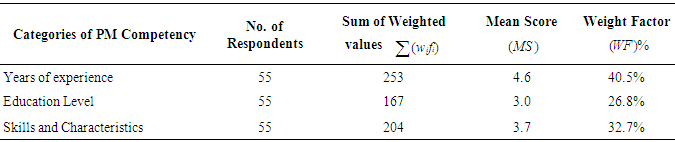

5.1. Analysis of Project Management Competency Elements

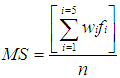

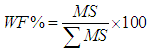

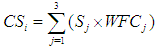

- This section discusses the results of quantitative analysis of the industry experts’ viewpoints on the significance of the main categories of project management competency and presents the weight factors calculated for each category.To analyze the results of Questionnaire A the rating scale measurement method was employed to determine the weight factor (WF%) of each category of project management competency. This is a commonly used research technique to analyze the results of survey tools in which participants provide their assessments of an object using a pre-defined numeric scale. The procedure established the mean score (MS) and the weight factor (WF) for three main categories of PM team competencies. These measures were obtained according to Eq. (1), Eq. (2) and Eq. (3):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

|

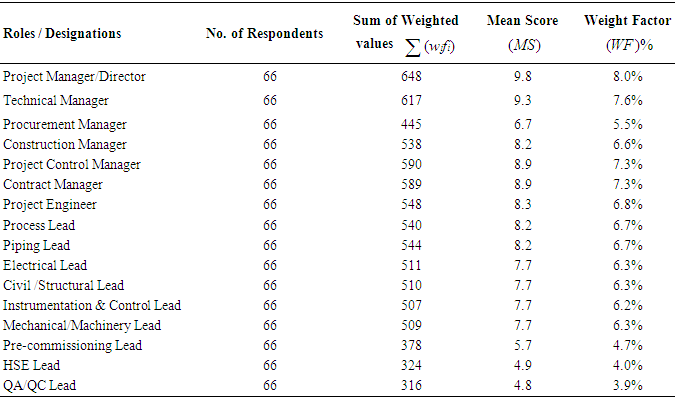

5.2. Analysis of Project Management Roles and Designations

- The second stage of the study (Questionnaire B) investigates the viewpoints of experts on the significance of different roles in a project management team contributing to design change management. A summary of different roles and designations in a project management team has been provided in Table 3.This list consists of the key roles contributing to design change administration including project managers, engineering managers, project control experts, design discipline leads, contract administrators, procurement and construction managers, and so forth. The results of data analysis—the sum of weighted values, mean score and weight factor for each role or designation in a project management team—are presented in Table 3. The values were calculated in accordance with Eq. (1), Eq. (2) and Eq. (3) with consideration of the parameters below and using the rating scale measurement method:Where: MS = mean score of perceived values for PM role/designation by respondents fi = frequency of responses for rating point i in the scale n = total number of responses wi = weight for rating point i in the scale i = rating 1-5 WF% = weight factor for each PM role / designation (%)The weight factors presented in Table 4 revealed that the project manager or director, the technical manager, the project control manager, and the contract administrator have the most significant contribution in administering design changes.

|

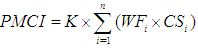

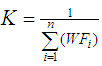

6. Project Management Competency Index

- A Project Management Competency Index (PMCI) is introduced by the authors to measure the overall competency level of a project management team in controlling and managing project design changes. The results of the industry surveys conducted on the significance level of the key elements of project management competency and the roles and designations of a PM team, are used to score the competency level.The PMCI score sheet consists of the list of key project management roles, each of which should be scored according to the evaluation criteria defined for the three main categories of project management competency and the relevant elements. The maximum score for each category of PM competency is 100. The scores for each of the categories are then aggregated to a weighted score for each PM role in accordance with Eq. (4), applying the weights obtained through the industry survey for the PM competency categories. Finally, the overall competency index of the team (PMCI) is calculated in accordance with Eq. (5) and Eq. (6):

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

=Project Management Competency Index i = PM team role/designation n = total number of PM team members

=Project Management Competency Index i = PM team role/designation n = total number of PM team members  = total score for category j of PM competency j = main categories of PM competency (1 = years of work experience, 2 = education level, 3 = skills and characteristics)

= total score for category j of PM competency j = main categories of PM competency (1 = years of work experience, 2 = education level, 3 = skills and characteristics)  = competency score for PM role i

= competency score for PM role i  = weight factor of PM role(compared to the other roles)

= weight factor of PM role(compared to the other roles)  = weight factor category j of competency

= weight factor category j of competency  factor (to normalize the WF as per the number of PM team members) Scoring is performed by evaluating the level of PM team capabilities considering the criteria defined for the main categories of PM competency. The criteria to evaluate different categories of PM competency and the relevant elements were defined through two brainstorming sessions by a focus group of three PM professionals experienced in oil industry projects. The outcome of these brainstorming sessions established the evaluation criteria for each PM competency category, which are then used in the PMCI score sheet to measure the competency level of a PM team (see Figure 4). A brief explanation of the evaluation criteria is provided in the following sections.

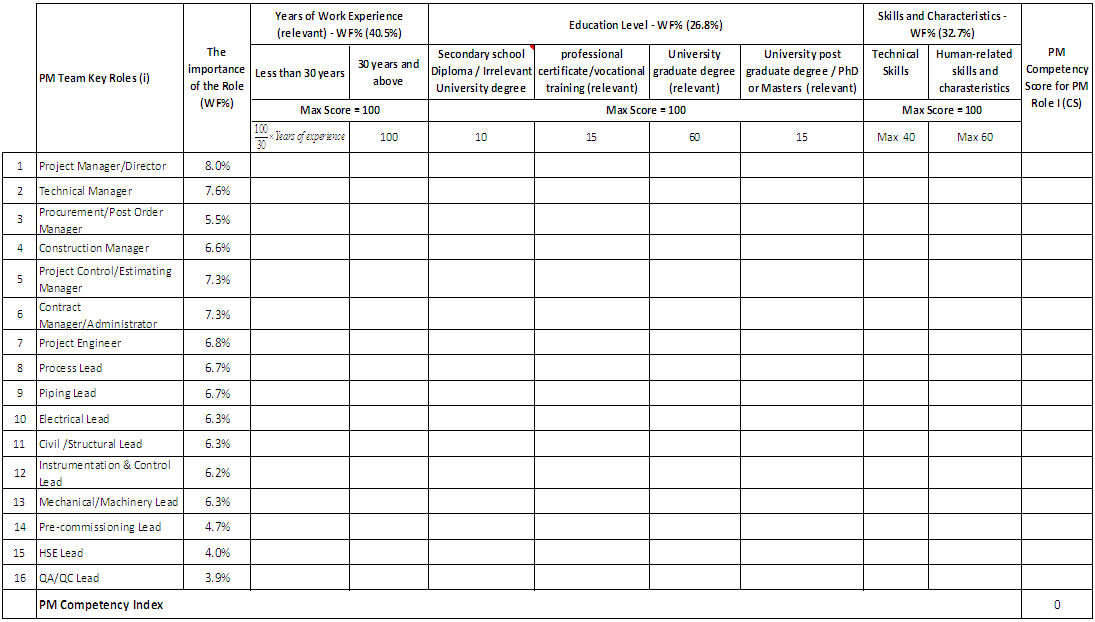

factor (to normalize the WF as per the number of PM team members) Scoring is performed by evaluating the level of PM team capabilities considering the criteria defined for the main categories of PM competency. The criteria to evaluate different categories of PM competency and the relevant elements were defined through two brainstorming sessions by a focus group of three PM professionals experienced in oil industry projects. The outcome of these brainstorming sessions established the evaluation criteria for each PM competency category, which are then used in the PMCI score sheet to measure the competency level of a PM team (see Figure 4). A brief explanation of the evaluation criteria is provided in the following sections. | Figure 4. PMCI score sheet |

6.1. Evaluation Criteria for Scoring Work Experience

- Assessment of an individual's work experience is based on the years of experience related to the project management role. Professionals having 30 or more years of relevant work experience should receive the maximum score of 100. The scores for individuals with less than 30 years of work experience are calculated by Eq. (7):

| (7) |

6.2. Evaluation Criteria for Scoring Education Level

- The education level of each member of a project management team is assessed based on the university degrees and the professional certificates or vocational trainings that they have received in project management or any other relevant field of study. For purpose of scoring, the education level has been broken down into four different levels, each of which has been assigned a predefined score: - Secondary school diploma / irrelevant university degree-10 points- Professional certificate/vocational training (relevant) – 15 points- University graduate degree (relevant) – 60 points- University post graduate degree / PhD or Masters (relevant) – 15 pointsThe total score that an individual may achieve is an aggregation of the scores assigned to the sub-divided levels. The maximum score assigned to education level is 100.

6.3. Evaluation Criteria for Scoring Skills and Characteristics

- Evaluation of an individual's skills and characteristics is a challenging and difficult task. To evaluate this project management competency component, PM skills and behavioural characteristics have been divided into the two categories of technical and human-related skills, with maximum obtainable scores of 40 and 60, respectively. Technical skills are assessed based on the expertise required for each role, as well as the essential skills required for project management team members to make trade-offs between cost, schedule, time, and quality. Human-related skills are evaluated considering soft skills related to personality, attitude and social skills. Some of the skills in this category include leadership, negotiation, communication, team-building, problem-solving, flexibility, and delegation. Table 5 lists the main technical and behavioral skills to be considered in evaluating each project management team member.

|

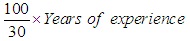

6.4. Example - Scoring the Competency Level of a Sample Project Management Team Using PMCI

- Figure 5 illustrates a PMCI score sheet completed for a sample project management team consisting of all the main roles and designations involved in administering and managing design changes. Data related to the team members’ work experience and education has been presented in Table 6.

| Figure 5. PMCI score sheet completed for a sample project management team |

|

7. Reliability and Validity

7.1. Reliability

- The reliability and internal consistency of the survey instruments were determined using Cronbach's α statistics through SPSS. Cronbach's α reliability coefficient normally ranges between 0 and 1. The reliability of data is considered low when Cronbach's α is less than 0.3 and high when more than 0.7 [59-61]. The Cronbach's α statistic calculated for both survey instruments—Questionnaire A (category of human-related factors) and Questionnaire B—had a value of 0.733 and 0.908, respectively. This indicates that there is an agreement between industry practitioners in ranking of the elements of PM competency and also the PM roles and designations. Accordingly, the survey instruments seem to be reliable tools to measure the weight factors of the items.

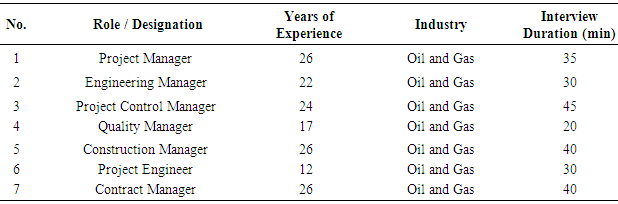

7.2. Validity

- Validation of the questionnaires was addressed by conducting two pilot studies with the participation of four and five industry experts for questionnaires A and B, respectively. The tools were then adjusted based on feedback received from the professionals.To validate the results, seven interviews were carried out with experienced experts dealing with design changes in the oil industry. The interviewees' profile is presented in Table 7. The majority of interviewees were senior experts with a strong work background on the subject of the study (average experience of 22 years in the industry), and had not participated in the questionnaire surveys. The interview questions sought the experts’ opinions on the unity and rationality of the results based on their experience in the industry.

|

8. Summary and Conclusions

- One of the main factors contributing to an effective project change management is the capability of PM team in handling changes. This study provides a tool for measuring the competency level of a project management team based on a three-staged survey conducted in the oil industry. The outcome of the study is a weighted index named the Project Management Competency Index (PMCI) used to assess the capability of a PM team in handling project design changes. This index can be employed by project stakeholders in the oil industry as an appraisal tool to proactively evaluate the competency level of a project management team at different stages of project execution. In the first two stages of the study, the main elements of PM competency and the roles and designations of a PM team were identified and weighted in order of importance using the input from two questionnaires administered in the industry. In the last stage, the index was developed through a number of brainstorming sessions with a focus group of project management experts. Ultimately, an example of a PMCI score sheet completed for a sample project management team is presented to illustrate application of the index.

9. Contributions

- The Project Management Competency Index (PMCI) provides a common forum for all project participants to assess and rate the competencies of a project management team. This index can be used as one of the variables contributing to evaluation and prediction of the impact of changes on project performance and accordingly can greatly enhance the predictability of project performance. Knowing the composition of a PM team, the team members' background and work experience, and their skills and characteristics at the first stage of a project would constitute an important step in forecasting the cost and schedule impact of changes on performance. The index evaluates and monitors the competency level of a PM team in handling design changes at different points during project execution, especially when there is a change in the PM team composition. This is crucial for selection of an effective PM team able to control and manage all issues related to project design changes.In addition to the above mentioned benefits, this index, in the long run, might highlight the competency areas that need to be improved through training programs.

10. Limitations and Implications

- While the findings of this study significantly contribute to an increased understanding of the main elements of project management competency and quantifying the team competency level, the research process and the results may be vulnerable to some limitations as with any study employing qualitative and quantitative research methods. These issues beyond the researchers' control include the sample selection and respondents' biases and lack of transparency. The sampling group was limited to a relatively homogenous group of professionals involved in managing project design changes in oil industry. This was to improve the internal validity of the survey, as a survey across practitioners with different backgrounds would create an excess amount of variation not relevant to the study. Another limitation is related to the complexities involved in gathering and scoring the information about people’s soft skills. Significant staffing turnover, and unavailability of data about skills and characteristics of project team members, may have a negative effect on the collection of data needed to measure the PMCI score of a project management team.Despite the above limitations, the outcome of this study was examined and validated through a number of interviews carried out with experienced industry practitioners. Moreover, the researchers strengthened the validity of the results by using triangulation sources of data through different data gathering techniques (i.e. questionnaire surveys, interviews, and focus group session).

11. Future Research

- Project Management Competency Index (PMCI) forms part of the researchers' future work focusing on development of a predictive model for pattern recognition of the impact of design changes on project performance. This index will be an independent variable in the predictive model that should be correlated to the variables related to the cost and schedule performance.It would also be interesting to correlate the project management competency score to project success indicators taking into account the combined effect of various factors.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML