-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2016; 5(1): 1-10

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20160501.01

Key Performance Indicators for Project Success in Ghanaian Contractors

Joseph Kwame Ofori-Kuragu, Bernard Kofi Baiden, Edward Badu

Department of Building Technology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

Correspondence to: Joseph Kwame Ofori-Kuragu, Department of Building Technology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Effective performance measurement is critical to project success. Unfortunately, common measures do not exist for the assessment of the performance of Ghanaian contractors. This paper develops a set of common key performance indicators (KPIs) for Ghanaian contractors. Following an extensive review of research on KPIs and performance measures from existing research and literature, the 10 most popular KPIs were identified. A survey of large Ghanaian contractors was conducted to find the KPIs most relevant to the local construction industry. The results of the survey were validated using expert interviews. A set of nine (9) KPIs has been developed for Ghanaian contractors as follows: Client Satisfaction, Cost, Time, Quality, Health and Safety, Business Performance, Productivity, People and Environment. These KPIs present a set of common criteria which can be used by Ghanaian contractors to measure and benchmark their performance and by client groups to compare contractor performance.

Keywords: Key Performance Indicators, Performance, Ghana, Contractors, Performance Measures

Cite this paper: Joseph Kwame Ofori-Kuragu, Bernard Kofi Baiden, Edward Badu, Key Performance Indicators for Project Success in Ghanaian Contractors, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 5 No. 1, 2016, pp. 1-10. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20160501.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

- Despite significant improvements in performance levels in the construction industries of many developing countries, the Ghanaian construction industry does not reflect this trend [23]. There is a widespread perception of poor performance and underperformance amongst Ghanaian contractors arising from a high frequency of delayed, abandoned or discontinued projects due to contractor non-performance. Many large-scale contracts are executed by foreign owned contractors or contractors with foreign backing [33]. Many projects show significant defects within the defects liability period and a poor maintenance culture affects many projects adversely. Most construction Clients in Ghana do not fully achieve anticipated project objectives [2]. Contractors may not provide adequate health and safety measures for both their employees and the general public. A high incidence of construction-related injuries and fatalities has led to calls by the government for contractors to emulate best-practice examples from more advanced countries to improve safety on construction sites [4]. With the commencement of commercial oil exploration in Ghana, it is important that Ghanaian construction firms are able to consistently deliver excellence both in their products and services to their clients. This will enhance their capacity to compete with international companies and participate actively in the delivery of the large-scale infrastructural platforms associated with the exploration and delivery of oil and related products [16]. There is a strong case for local contractor participation in the delivery of major infrastructural projects [16], however this expectation needs to be matched with sufficient capacity amongst Ghanaian contractors to deliver to the standards of world-class project excellence which major international participants in the oil industry are accustomed to in their home countries. This is particularly significant given the projected upsurge in infrastructural development and progressive efforts to raise finance for major infrastructure development in Ghana [19] to address the huge infrastructure deficit. To enable performance excellence in the delivery of such infrastructure projects in the Ghanaian construction industry calls for innovative solutions [22]. The development of a set of KPIs customised for Ghanaian contractors will contribute to the delivery of excellence in the management of construction projects in the Ghanaian construction industry.

1.2. Research Problem

- Despite the significant role of the industry to Ghana’s economy, the performance of Ghanaian contractors is a major cause of concern amongst client groups and other stakeholders. In many instances, contractors are blamed for poor performance and criticised for having limited knowledge in the application of requisite management techniques [2]. In many construction firms, management of resources is undertaken haphazardly and therefore does not promote growth within these firms [35]. There is a general perception in the Ghanaian society of widespread poor and underperformance amongst Ghanaian contractors. [22] explored the problems which affected Ghanaian construction firms. Those identified as affecting the contracting firms include the inability to secure adequate working capital, inadequate management, insufficient engineering capacity and poor workmanship. Performance measurement has been identified as being essential to any efforts to improve performance [8] and a cornerstone to efforts to attain world-class performance [3]. Both the government and major contractor groups in Ghana identify the lack of performance measuring tools for Ghanaian contractors as a major cause of poor project delivery. The Ghana government has, in a bid to improve project delivery, expressed the need for a performance measurement tool for contractors as a means of ensuring that projects are awarded only to competent contractors [36]. Whilst the development of a performance measuring system for Ghanaian contractors will help contractors improve their performance and improve the efficiency of procurement, its effectiveness is dependent on the selection and use of relevant performance measures and indicators to provide a sound basis for assessing performance [11]. Unfortunately, there are no common indicators which can be used to assess the performance of Ghanaian contractors and the level of awareness of performance indicators and measures among Ghanaian contractors is low [24].Some significant research on performance indicators exist which can be adapted for use by Ghanaian contractors. However, the sheer numbers available creates “paralysis by analysis” [26] where the failure to identify the correct performance measures to use leads to inaction. Too many or inappropriate performance measures can easily create a deterioration in performance. An effective approach to selecting performance measures is to identify the minimum set of measures which can establish whether the overall performance is acceptable or otherwise [26]. In this paper, existing studies on performance indicators and measures from several industries are reviewed to identify the most commonly used key performance indicators (KPIs) as a step to identifying a suite of KPIs for Ghanaian contractors.

1.3. Aim

- The purpose of this paper is to establish the relevance of KPIs to construction project success, identify the most important performance measures and adapt a set of key performance indicators (KPIs) for use by Ghanaian contractors.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Ghanaian Construction Industry

- The Ghanaian construction industry is the backbone of the Ghanaian economy contributing about 8.5% to the overall Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employing 2.3% of the active population [4]. Ghana’s Ministry of Water Resources Works and Housing (MWRWH) had over 20,000 “building contractors” on its register in 2000 [5] rising to about 50,000 registered contractors in 2010. The number of registered contractors is very large relative to the size of the Ghanaian economy. The Ministry of Road and Highways (MRH) and the Ministry of Works and Housing (MWH) are responsible for the policies that have an effect on the construction industry in Ghana [35]. Both Ministries are responsible for the registration and classification of contractors – road contractors by the former and building and civil engineering contractors by the latter respectively. However, neither ministry has a monitoring or regulatory function with respect to contractor performance. All Ghanaian contractors are required to register with the Registrar General’s Department with a requirement to submit annual returns. This requirement is however not strictly enforced and there are no published sanctions for non-compliance [24].

2.2. Performance and Excellence

- Several definitions of “performance” have been proposed in the literature reviewed. Amongst others, it has been described as the valued productive output of a system in the form of goods and services. The term “performance” denotes the degree to which an operation fulfils primary measures in order to meet the needs of the customers. Units of performance describe the actual fulfilment of the goods and services relating to performance and are measured in terms of the features of production, quality, quantity and / or time [26]. [2] defines “performance” in competency terms as the behavioural competencies that are relevant to achieving the goals of project-based organisations The key themes in the review for this paper on definitions of performance describe the concept in terms of the achievement and fulfilment arising from an operation in relation to set goals however each definition uses different measures. The Baldridge National Programme identifies four (4) types of performance: product and service, customer-focused, financial & marketplace and operational [7]. Whilst these classifications are representative of performance, their respective emphases are different.

2.3. Performance Measures and Indicators

- A Performance Measure is a metric which is used for quantifying the efficiency and effectiveness of action [31]. There are short-term metrics and short-term measures which have to be continually calculated and reviewed [37]. Performance measures may be described as short term measures which may be calculated or reviewed to provide an indication of performance. [7] does not distinguish between “measures and indicators” describing both as numerical information used to quantify the input, output and performance dimensions of processes, products, programmes, projects, services and the overall outcomes of an organisation.

2.4. Selecting Performance Measures

- The subject of performance is vast with numerous authors continuously adding to the body of literature on the subject. Between 1994 and 1996 for instance, one paper or article on “performance” appeared every five hours of every working day [8]. The sheer numbers of organisational performance measures can lead to inaction amongst project managers. Too many, too few or inappropriate performance measures can easily create a deterioration in overall performance [26]. This is especially true in situations where experience of performance measurement is scant, as is the case amongst Ghanaian contractors. Bringing the extensive existing knowledge, past research and literature together will help simplify the processes for selecting performance measures by Ghanaian contractors. An effective approach to selecting performance measures is to identify the minimum set of measures which can help make effective judgements on the standards and extents of performance to establish whether the performance of a process is acceptable [26]. The selection of performance measures should consider measures which reinforce the activities that are in the best interest of the company. Organisations should align the reasons for implementing a performance measurement system with the need to improve overall effectiveness of the business process [1] before trying to identify the possible factors that can be measured. Performance measurement generally involves identifying a balanced set of measures, measuring what matters to service users and other stakeholders, involving staff in the determination of the measures making sure that both perception measures and quantifiable performance indicators are included [21].

2.5. Performance Measures from Literature Review

- The main performance measures used by English Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) as follows: productivity, quality performance, financial, innovation, employee learning, customer performance, meeting customer requirements, customer satisfaction and delivery for the customer [31]. The [31] SME measures appear to have a general applicability to entities of all sizes. This provides a broad base for measuring performance covering many performance areas unlike [18]’s Balanced Scorecard which uses four (4) broad groups of performance measures: financial, learning and growth, customer and internal processes. The limited scope of the Balanced Scorecard’s measures makes its more suited to entities with prior experience of KPIs. [11] used 6 performance measures: quality, delivery reliability, customer satisfaction, cost, safety and morale. The measures developed in [11] introduced a relatively novel measure of performance – morale – which though an essential success factor is not commonly used as a measured indicator. [25] explored how world-class performance is affected by ISO 9000 and Total Quality Management (TQM). Six (6) indicators of best practice and performance are identified as follows – leadership, people, processes, people satisfaction, customer satisfaction and operational performance. [28] refers to 14 performance measures as follows: cost reduction, waste reduction, quality of products, flexibility, delivery performance, revenue growth, net profits, profit to revenue ratio and return on assets. The rest of the [28]measures focus on financial measures including investment in R & D, capacity to develop a competitive profile, new products development, market development and market orientation. Non-financial measures like productivity, employee training and customer requirements help to ensure balanced business and organisational growth [31].The use of performance measures is an effective way to increase business profitability and competitiveness with financial measures the predominant option. The reluctance to adopt newer performance measures can be attributed to the fact that neither industry nor academia have agreed on what new measures to use, a situation which is not made any easier by the ever growing list of performance measures [32]. [32] proposes the following performance measures: financial, activity based costs, productivity measures, cost measures, quality measures, speed measures, dependability measures and flexibility measures but excludes customer-related measures, a very important measure of performance.The MBNQA is the top-most quality award that rewards organisations which attain performance excellence in the United States of America (USA). [7] outlines the performance measures used in MBNQA as follows: leadership, strategic planning, customer focus, workforce focus, operations focus, measurement, analysis and knowledge management and results.

2.6. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

- KPI is a measure of performance of an activity critical to organisational and project success [12]. KPIs in construction enable measurement of project and organisational performance throughout the industry [34]. KPIs have been used to introduce many construction firms to performance measurement. [8]. Examples of construction industry KPIs groups are now discussed.

2.6.1. The UK KPI Working Group KPIs

- Following the Egan Report, [34] developed a KPIs Framework for the UK construction industry with seven (7) groups. These are: time, cost, quality, client satisfaction, client changes, business performance and health & safety and are categorized into headline, operational and diagnostic indicators. The Headline Indicators provide a measure of the overall “rude” state of health of a firm, Operational Indicators bear on specific aspects of a firm’s activities and should enable management to identify and focus on specific areas for improvement, whilst Diagnostic Indicators provide information on why certain changes may have occurred in the headline or operational indicators [34].

2.6.2. UK Construction Industry KPIs

- In the UK, Constructing Excellence publishes KPI Wall charts each year for different groups in the UK construction industry. These are: the UK Economic KPIs (all construction), Environment KPIs, Respect for People KPIs, Consultant KPIs, and Construction Products KPIs, Repairs & Maintenance and Refurbishment (Housing) KPIs, Repairs & Maintenance and Refurbishment (Non-housing) KPIs, Housing KPIs, Infrastructure KPIs and ME Contractor KPIs. ME Contractor KPIs are prepared by Building Services Research and Information Association [12].[12] provides additional information on UK construction industry KPIs which falls into three categories as follows:i. KPI charts for major sub-divisions; ii. Graphs that provide additional analysis of the headline KPIs; and iii. Extra indicators requested by users (e.g. contractor satisfaction with client).

2.6.3. Scottish Construction Industry KPIs

- Introduced in 2007 by the Scottish Construction Centre (SCC), the Scottish Construction Industry (SCI)’s KPI Framework aims at encouraging organisations at every level within the SCI to adopt performance measurement. It comprises of 9 KPI streams: product, service, quality, time, cost, safety, environment, people and business [29]. The SCI KPIs are based on the KPI suite developed by the KPI Woking Group for the UK Construction Industry. The main difference is with the inclusion of “environment” in the SCC KPIs. Whilst this reflects the increasing relevance of environmental considerations in the built environment, it is not a prominent feature in construction KPIs globally.

2.6.4. Rethinking Construction KPIs

- The Rethinking Construction Report developed by the Department of Environment, Transport and Regions (DETR) in the United Kingdom (UK) identified seven (7) indicators of performance in which contractors should aim to improve performance – capital cost, construction time, predictability, defects, accidents, productivity and turnover & profits with year-on-year improvements targeted across the industry [14]. Such measures should allow management and project managers to evaluate year-on-year performance and be SMART – specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and timely [27]. The Rethinking Construction KPIs are broadly representative of a common set of indicators used in the UK construction, a trend also seen in the Scottish Construction Industry KPIs, Construction Excellence KPIs, the UK KPIs Working Group KPIs and the KPIs used in other sectors of the UK construction industry. They are derivatives of the UK KPIs Working Group KPIs. The Rethinking Construction KPIs form the basis of subsequent developments in UK Construction KPIs for the different sectors of the industry.

2.6.5. Danish Construction Industry KPIs

- Since 2005, Danish contractors bidding for jobs need to demonstrate competence in fourteen (14) KPIs developed by the Benchmark Centre for the Danish Construction Sector (BEC) as follows:1. Actual construction time;2. Actual construction time in relation to planned construction time;3. Actual construction time;4. Remediation of defects during the first year;5. Number of defects during in handing-over; 6. Accident frequency;7. Contribution ratio;8. Contribution margin per man hour;9. Contribution margin per wage crowns 10. Work intensity in man hours per m;11. Labour productivity;12. Changes in project price during the construction;13. Square meter price; and 14. Customer satisfaction with construction process. (Source: [9].)According to [10], since 2010, a new set of seven (7) KPIs have been used to benchmark contractor performance for Danish contractors. These are: 1. Actual construction time in relation to planned construction time;2. Number of defects entered in the handing-over protocol.3. Economic value of defects;4. Defects in delivery;5. Accident frequency;6. Customer satisfaction with the construction process; and 7. Customer loyalty.Whilst the main thrusts of the two versions of the Danish Construction KPIs are similar, there are significant variations. The 2006 version has fourteen (14) measures whilst the 2014 version has ten (10) measures grouped into seven (7) headline measures. In terms of their scope and coverage, the former has a broader scope and is better representative of the construction industry.

2.6.6. KPIs for United States of America (USA) Construction Industry KPIs

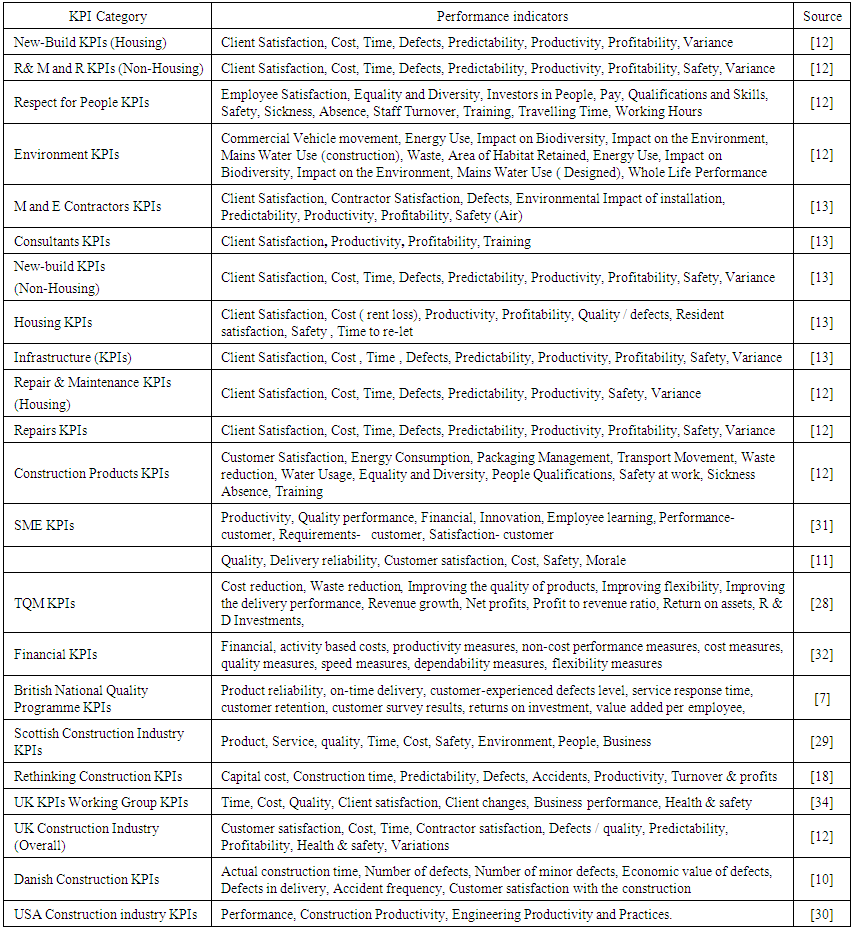

- The Construction Industry Institute of the USA uses 4 KPIs in an online performance measurement system for contractors as follows: Performance, Construction Productivity, Engineering Productivity and Practices. [30]. These KPIs are broken down into subsections to make it easy to use.Table 1 shows all the KPI groups which were reviewed in developing a set of KPIs for Ghanaian contractors.

| Table 1. Summary of KPIs from literature reviewed in this paper |

2.6.7. Summary

- The review for this paper covered a broad range of KPIs from the construction industry. The review shows that there are many existing KPIs, a situation which makes it difficult for entities with little experience of KPIs to choose suitable KPIs for measurement. Despite the many different KPIs seen in the review, it is apparent that some of the measures are used more often in the KPIs in use. The more commonly occurring KPIs could be the basis for the KPIs to be developed for Ghanaian contractors. Especially for the construction related KPIs, there seems to be a common theme with measures such as Time, Cost, Quality, Defects, Productivity etc.

3. Methodlogy and Methods

3.1. Methodology

- The major research paradigm for construction and built environment research has been mainly positivistic and quantitative. As a later development, a qualitative constructivist paradigm employing interpretivism, grounded theory and ethnomethodology was largely used [15]. The emerging trend for research in the construction and built environment employs multi-methodology based on triangulation [15], 2010). This approach uses methodical pluralism and recommends the use of multiple theoretical models and methodical approaches in research [15] as a means to understand complex situations. In this paper, methodical pluralism is addressed by the integration of the outcomes of the literature study, field research and the validation exercise using expert interviews. To validate research outcomes, [2] recommends getting experts comments on relevant aspects of the research. This approach to validation is used in [1] where review meetings are held with a panel of experts to validate research outcomes. [1] used a panel of 12 experts comprising eight (8) from industry, professional and trade associations and four (4) academics. [20] adopts the epistemological validation approach in which research outputs are validated against existing knowledge to assess the extent to which the outputs conform to literature on existing frameworks.

3.2. Methods Used for Study

- Following an extensive review of research on KPIs, metrics and performance measures from existing research and literature the most popular KPIs were identified. Altogether, 21 sets of KPIs drawn from a broad range of industries were reviewed. The most popular KPIs were identified from the 21 KPI groups reviewed by counting how many times each KPI appeared. The 10 KPIs which appeared most were selected. Using structured questionnaires, a survey of large Ghanaian contractors was conducted to explore their perceptions of which of the 10 most popular KPIs identified from the literature review were most relevant to the local construction industry. The results of the survey were validated using expert interviews.

3.3. Population and Sample Size

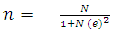

- According to Ghana’s Ministry of Water Resources Works and Housing (MWRWH) which keeps a register of all Ghanaian contractors in the respective classes, there were 139 D1K1 contractors in Kumasi and Accra in 2010. “D1K1 contractors” refer to the largest of four contractor financial categories in Ghana. The categories are based on the maximum size of projects they can undertake. D1K1 contractors are not limited as to the size of project they can undertake. The survey was restricted to Accra and Kumasi because experience showed that almost all the D1K1 contractors are based in these two largest cities in Ghana. Where they operate outside Accra and Kumasi, they tend to maintain an office in these cities so it was administratively easier to work with these contractors. Also it was felt that the subject of the study would be most relevant to the largest contractors would be most likely to have or be interested in KPIs. Thus the population size, N for D1K1 contractors is 139. Given that N is less than 200, the entire population should have been sampled using the census approach to sampling [17]. However, in the absence of a central database of contractors and with much of the information at registration out-of-date, it was impossible to identify all the contractors in the population. The sample size was calculated mathematically to give a more precise sample for the research. According to [6], the level of risk that a sample selected will not show the true value of the population is reduced for confidence levels of 99% and increased for a lower confidence of 90% or lower. A level of 95% was thus chosen for the survey. With a confidence level of 95%, the sample size, n was obtained using the [17] formula as follows:

| (1) |

approximated to 103.Add 30% to compensate for non-responses and non-returns, i.e. 30% of 103 = 30.9 approximates to 31 questionnaires added for non-responses. Adding 31 to 103 gives 134, therefore a total of 134 questionnaires were distributed of which 79 were returned. For the sample size of 103, this constitutes a return of 76.699 which approximates to a 77% returns rate for the questionnaires.

approximated to 103.Add 30% to compensate for non-responses and non-returns, i.e. 30% of 103 = 30.9 approximates to 31 questionnaires added for non-responses. Adding 31 to 103 gives 134, therefore a total of 134 questionnaires were distributed of which 79 were returned. For the sample size of 103, this constitutes a return of 76.699 which approximates to a 77% returns rate for the questionnaires.3.4. Questionnaire Design

- The first part consisted of questions which were used to collate information about respondents. Question 1 asked the respondents to indicate the type of entity they represented and for contractors their financial class. This was to identify eligible respondents to the questionnaires. In question 2, contractors were asked to indicate the number of employees which gave an idea of the size of the company. The next question asked respondents to indicate the number of employees with University level education. This gave an indication of the calibre of human resources in the company. Lastly for this section, respondents were asked to describe the scope of operations of the company – local (district level), regional or national. These questions helped to ensure that respondents met the sampling criteria. In order to encourage more contractors to answer the questionnaires, the questionnaires were answered anonymously. In the second section, respondents were asked to indicate their opinions of which of ten (10) selected KPIs identified from the literature review were most relevant for Ghanaian contractors using a Likert scale. Respondent contractors were asked to assess the importance of the ten (10) selected KPIs and whether they should be included in the list of KPIs for Ghanaian contractors. The survey used a Likert scale of 1 to 5 where 1 meant extremely unimportant, 2 meant unimportant, 3 meant somewhat important, 4 meant important and 5 meant extremely important. Spaces were also provided for respondents to add on any additional measures they considered relevant and suggested should be included in the final list of KPIs for Ghanaian contractors.

4. Analysis of Survey Results and Validation

4.1. Survey Results and Analysis

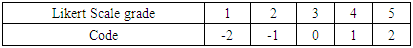

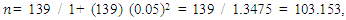

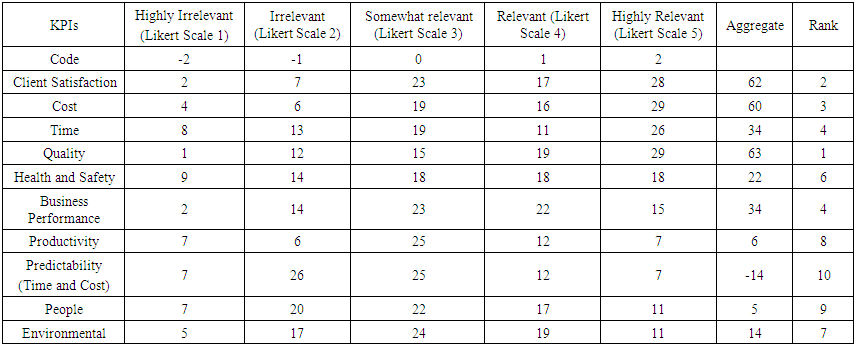

- The field survey of Ghanaian contractors focused on D1K1 selected randomly from lists provided by the Ministry of Works and Housing (MWH). A structured questionnaire was used to reduce variability in the answers provided by respondents. The survey instrument was used to further explore the key issues arising from the literature review to develop a deeper understanding of the issues. Leading Ghanaian contractors and financial institutions were surveyed using the structured questionnaires. The results and key findings of the survey of Ghanaian contractors are now presented, analysed and discussed.Of the 134 questionnaires sent out, the 79 returned representing 77% returns which indicated a very good returns rate [6]. In the structured questionnaires, respondent contractors were asked to assess the importance of the ten (10) selected KPIs to the Ghanaian construction industry and whether they should be included in the list of KPIs for Ghanaian contractors. The questions were designed to assess the extent to which the KPIs selected from the review of literature and existing KPIs were relevant to the Ghanaian context. Choosing options 1 and 2 on the scale was indicative of KPIs deemed to be of little or no relevance to Ghanaian contractors. Option 3 represented “neutral” and respondents choosing this for specific measures were of the opinion that the measures involved may or may not be included in the KPIs for Ghanaian contractors. However, the choice of options 4 and 5 represented measures which in the opinion of respondents should be included in the Ghanaian contractor KPIs. To analyse the results, the 5 categories in the Likert Scale were coded as shown in Table 2.

|

| Table 3. Survey results on relevance of KPIs to Ghanaian contractors |

4.2. Validation Interviews

- Following the analysis of the survey results, expert interviews were conducted with selected experts drawn from a broad spectrum of the Ghanaian construction industry to validate the findings of the study. The interviews were conducted using semi-structured questionnaires based on the findings of the initial survey. In all, 10 Ghanaian experts were targeted including contractors, consultants, academics and researchers drawn from the construction industry. Respondent contractors were selected to include a large, medium and a small contractor respectively to ensure that feedback was provided from different perspectives. Respondents were selected carefully to ensure they were experienced professionals in their respective fields with a minimum of fifteen (15) years’ experience.

4.2.1. Feedback from Validation Process

- Respondents were asked to comment on the outcome of the survey and make suggestions for the final list of KPIs for Ghanaian contractors. The questions sought to establish whether the respondents agreed with the outcome of the analysis which concluded on nine (9) measures of performance as the KPIs for Ghanaian contractors. All ten respondents agreed with the appropriateness of the ten (10) measures selected from the literature review to be included in the KPI suite for Ghanaian contractors. Three of the experts interviewed were of the opinion the ten KPIs be maintained whilst seven favoured nine KPIs in line with the survey results. The majority view which supported the survey results was thus taken. Suggestions made by the experts with no more than one person supporting were discounted.

5. Discussion

- Whilst the performance of Ghanaian contractors continues to be a cause for concern, it is the expectation that adopting a set of KPIs will help contractors measure their performance as a means to improving overall performance levels. The KPIs developed in this paper were part of a larger pool identified from the literature study and from existing KPIs in leading economies with well performing construction industries. These have been adapted to the Ghanaian construction industry. This has been achieved using a survey of large Ghanaian contractors in order to get the Ghanaian contractor perspective of the KPIs drawn from a variety of sources. The approach to this study, using triangulation ensures that the outcomes of the literature study, questionnaire-based survey and the validation using expert interviews ensured that the findings from the respective stages mutually reinforce each other and increases the validity of the results. The high returns rate for the survey could be due to the high interest shown in the subject by the respondents and in part to a short questionnaire design which made it easy to complete and return the questionnaires. The returns rate of 77% shows the respondent group as a good representation of the sample and thus reinforces generalisations that can be made for the overall Ghanaian construction industry.The analysis of the results showed that amongst the respondents, Quality is the most relevant KPI for Ghanaian contractors. This is followed by closely by Client Satisfaction and Cost. The overall aggregated scores for these three measures show proportion of the respondents who deem these as being of high relevance and by extension, the extent of their importance to Ghanaian contractors. Time, Business Performance and Health and Safety are also rated quite highly by the respondents even if the indication is one of reduced relevance to the Ghanaian contractors than the top three measures. Environment, Productivity and People complete the order of relevance with reduced overall aggregate scores. From the analysis, the only measure which recorded a negative aggregate score – Predictability – is excluded from the final list of KPIs for Ghanaian contractors. This measure relates to Predictability of Time and Cost respectively for the project. The exclusion of this measure should not affect the overall effect of the KPIs since Cost and Time are individually included in the final list of nine KPIs even if their emphasis are different.The inclusion of Quality, Cost and Time in the first four KPIs generally conforms to popular construction management literature which identify these measures as the ultimate objectives of every construction client. The inclusion of Client Satisfaction – in second place – also conforms to popular literature on KPIs in the construction industry. The nine KPIs proposed in this paper are not necessarily the only important KPIs. They are the ones deemed to be most relevant to Ghanaian contractors. These KPIs can be used as the starting point for Ghanaian contractors new to KPIs and Performance Measurement. They can be used by Ghanaian contractors as the basis for benchmarking performance against the best-in-class organisations, measuring performance and setting targets for improving their performance to internationally competitive levels. As a performance measurement tool, the KPIs developed can be used by third party groups such as potential clients and consultants as the criteria for assessing the performance of Ghanaian contractors. They present a set of criteria which Ghanaian contractors can select from for targeted improvement. Subjecting the survey analysis to further validation by a panel of experts from the Ghanaian construction industry in line with the concept of triangulation confirms the suitability of the KPIs for Ghanaian contractors.

6. Conclusions

- There are significant numbers of performance measures in use and the sheer numbers of measures can present problems for project managers. Too many, too few or inappropriate performance measures can affect overall performance negatively. In this paper, existing KPI groups were explored to identify the most popular KPIs which have been adapted for Ghanaian contractors. This is the first formal set of KPIs for Ghanaian contractors and the Ghanaian industry generally. Popular KPIs identified from literature were subjected to a survey of selected Ghanaian contractors. Findings from the survey were validated through interviews with a panel of experts. It has been established in this paper that the use of performance measures is an effective way to improve project management success. In this paper, a suite of nine (9) KPIs has been developed for Ghanaian contractors which can be used for performance measurement. The KPIs in order of relevance to Ghanaian contractors are: Quality, Client Satisfaction, Cost, Time, Business Performance, Health and Safety, Environment, Productivity and People. These KPIs can be used for measuring performance, comparing performance with global leaders and setting targets for improving performance to internationally competitive levels. The KPIs developed in this paper can also be used by clients and other third party groups as the criteria for benchmarking and assessing the performance of Ghanaian contractors.Further work may focus on developing graphs for the KPIs developed in this paper to make them easier to use. Based on performance levels of the best-in-class Ghanaian contractors, these graphs will help Ghanaian contractors to easily compare their performance with benchmark organisations. It is also proposed that further study be conducted to develop methods for measuring the qualitative indicators in the KPI suite developed in this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML