-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2015; 4(6): 238-247

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20150406.03

Safety Performance in the Construction Industry of Saudi Arabia

Ibrahim Mosly

Civil Engineering Department, College of Engineering – Rabigh Branch, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Ibrahim Mosly, Civil Engineering Department, College of Engineering – Rabigh Branch, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The construction industry is well known for being one of the most dangerous industries worldwide. It is labor intensive and requires much movement of materials and machinery within a confined area, leading to a high level of safety hazards. In Saudi Arabia, the construction industry is considered a major contributor to work accidents. The current poor record of safety measures within the construction industry is leading to a high rate of accidents. The private sector of the construction industry in Saudi Arabia seems to be the primary source of these accidents, specifically in small- to medium-sized projects. This study aims to investigate the safety performance of small- to medium-sized construction projects in the private sector of Saudi Arabia through observation. The research investigates a number of safety aspects under five groups: 1) general – construction site; 2) workers’ personal protective equipment (PPE); 3) heights and fall protection; 4) machinery; and 5) excavation. The findings suggest that there is an urgent need for the improvement of safety performance in the construction industry of Saudi Arabia and a number of recommendations that can assist in the enhancement of safety in the industry are proposed.

Keywords: Construction, Safety, Observation, Saudi Arabia

Cite this paper: Ibrahim Mosly, Safety Performance in the Construction Industry of Saudi Arabia, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 4 No. 6, 2015, pp. 238-247. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20150406.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Historically, the construction industry has been amongst the highest-risk industries [1]. Unfortunately, this has not changed in modern society, where the construction workplace is still recognized as one of the highest-risk occupational locations [2]. Despite the substantial improvements achieved in safety through the years, the rate of accidents is still the highest in the construction industry [3]. For example, the number of accidents in the construction industry is higher than any other industry in Saudi Arabia [4]. This is also the case in many countries worldwide. In the United States, efforts are made to reduce the risks of injuries and illness in the construction industry, but it is still considered one of the most dangerous industries in the country [5]. In Malaysia, similarly, the construction industry is considered a major economic force and one of the most hazardous industries [6]. Furthermore, in China, construction site safety records are poor when measured by international standards [7]. Studies also imply that injury rates and cost rates are the highest in the construction industry, compared to the average across all other industries [5]. The accidents that occur in the construction industry can have severe consequences on the workers and public [3]. In Saudi Arabia, the total number of reported work accidents in 2014 was about 69,241 accidents [4]. The construction industry accounted for 51.35% of these accidents [4]. This high percentage could be due to many factors related specifically to the construction industry, e.g., construction sites are known for being dynamic with a constant changing environment [1, 3, 8-10], where it is normal to have a number of work teams in the same area of the construction site working on different tasks and changing as the project proceeds [3]. The fact that the workers are not from the same background and working in the same space might cause many hazards. Furthermore, having different contractors and subcontractors in the same construction site requires coordination; otherwise, there is a chance for an increased risk of injury [1]. Another contributing factor could be the low safety performance on construction sites. Poor safety performance causes a greater risk of workers facing work-related injuries or fatalities [11]. For example, a number of workers resist safety rules because they believe it makes their lives more complex [10], increasing the numbers of accidents that occurs due to the many hazards at the workplace. A large number of activities that are carried out during the execution stage of construction projects are potentially hazardous to the safety and health of workers [3]. They might cause physical injuries, long-term illnesses [6], or death [12]. A study showed that the two main reasons for the high rate of accidents in the construction industry are: (1) the basic risk due to the environment and characteristics of construction projects and organizations; and (2) the extra cost burden of additional safety measure implementation in a competitive and growing market [3].This research aims to explore the safety performance in the construction industry of Saudi Arabia, specifically in small- to medium-sized private construction sites. The study will be made in the city of Jeddah which is the country’s second largest city after the capital, Riyadh [13]. The population of Jeddah is estimated to be approximately 3.4 million [13]. The city of Jeddah is located in the western region of Makkah al-Mukarramah of Saudi Arabia [14]: this region is responsible for the highest number of work accidents in 2014, at 23,764 accidents, which represents 34.3% of the total work accidents in 2014 [4]. The construction industry is accountable for 12,438 of these accidents, i.e., approximately half of the total work accidents in the region [4]. The aforementioned statistics made the selection of Jeddah city an excellent choice for the purpose of this research. In this paper, the first section, entitled ‘Introduction’ provides a general idea on the problem to be studied. The second section presents the outcomes of the literature review on the subject. The third section describes the research methods undertaken. The fourth section illustrates the results of data analysis with discussion. The final section includes the conclusions and recommendations regarding this research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Management of Safety Accidents

- It is common for accidents to occur in construction sites when hazards are present in the workplace area. Hazards must be managed through implementation of safety principles and guidelines to avoid these accidents. The following definitions are important to clarify the relationships between hazard, risk, and harm. Firstly, a hazard is defined as anything that has the potential to harm people [15-17]. Secondly, a risk is defined as the possibility or likelihood that a hazard will harm people [15-17]. Thirdly, harm is the result of a hazard or risk occurring and causing death, injury, illness, or disease to a person [15]. Before a hazard harms a person, a sequence of events must occur first [15]. Thus, understanding the sequence of events that occurs before the person is affected will provide important information on methods to control the risk of a hazard [15]. The main hazards in the construction industry include: falls from height, injuries in excavations, tripping or sliding due to a wet surface, being hit by falling objects, injury from moving heavy loads, working in bad confined spaces, being injured by a workplace vehicle, hand tool injury, dust inhalation, rough material handling, contact with dangerous substances and radiation, drowning in water, exposure to loud noise and vibration from machinery [18]. These potential hazards must be considered by safety personnel on construction sites for the safety of workers and temporary visitors. To plan for construction safety is to make sure that necessary measures are made to mitigate possible hazards [19, 20]. Therefore, a reliable source of information on safety hazards and measures is needed for construction management [20]. It will promote safety performance on construction sites by enabling construction managers to be aware of hazards and risks [20]. Traditionally, management of health and safety risks in supervising site activities has been the responsibility of the main contractor [8]. On a wider scope, occupational, safety, and health management should be conducted at all levels of the construction team from the top management down to the workers at the site [11]. Hence, all stakeholders must be involved in construction site safety to cover the different aspects from diverse perspectives. Safety performance can be affected by the following main factors: top management and project managers’ poor safety awareness, lack of training, reckless operations, and poor safety resources [7]. Assessment must be made for planned activities and the protection of all affected parties should be sought out when dangerous work methods are anticipated [19]. Early planning for safety can reduce the chances of hazard occurrence and thus improve safety performance. Occupational safety methods traditionally included enforcement of regulations, standards, guidelines, best practice consideration, accident statistics, investigation and inspections, study of safety management systems, and personal behavior [21]. Standards should be set by governments that can legally enforce them to ensure penalties for none-compliance [9]. These standards must be acceptable to the community as a whole [9]. Legislation must also be fair and acceptable to the workers in the field so they can implement them. A research study showed that, for the group of workers who participated in the study, legislation related to occupation, health, and safety were not respected because they did not believe that many of the rules addressed their real safety concerns [10]. One of the main causes for not considering safety measures at site is cost. Many people do not feel that it is critical for the success of the project to spend money on safety [9]. Therefore, in the case of budgetary constraints, it is normal to cut back on the cost of safety [9]. A study on occupational risk assessment in the construction industry summarizes a number of causes that influence safety performance in the construction industry from literature into the following [1]: (1) poor work and safety; (2) size of company; (3) lack of coordination; (4) cost-effectiveness and time pressure; (5) lack of consistent data; (6) poor communications; (7) workers’ poor involvement in safety matters; (8) constantly changing worksites; (9) workers’ specializations; (10) workers are responsible for their own protection and their workplace; (11) inadequate training and worker fatigue; (12) inadequate equipment selection, use, or inspection; (13) poor safety awareness; (14) unavailability of prevention/protection equipments; (15) long distance between construction jobs; and (16) workers face long-term health risks and the fear of not having a regular paycheck.

2.2. Safety in the Construction Industry of Different Countries

- Risks related to construction work are well known, yet the industry is still a leader for elevated injury, illness, and fatality rates affecting business, society, and families [22]. It is unreasonable for the construction industry to remain hazardous with the wide presence of statistics, causal factors, and managing measures for risk reduction [22]. The safety and health performance of contractors must be investigated at construction sites [11]. Occupational accidents are considered a major source of risk; thus occupational health and safety is a major concern for many countries [21]. For instance, in Turkey, many work injuries are not recorded and documented due to the absence of a proper classification or documentation system, as well as the high number of unregistered workers [23]. Thus, realistic data on safety performance in the construction industry of the country is unavailable. Furthermore, unskilled workers are regularly engaged in skilled positions in the Turkish construction industry, where most of these unskilled workers come from rural areas and many are temporary cheap labor [23]. It becomes difficult to improve safety conditions and the construction culture with untrained and inexperienced workers [23]. Similarly, in China, safety management in the majority of Chinese construction firms is very low for a number of reasons, including [7]: (1) lack of suitable safety management system records; (2) few contractors provide the necessary personal protective equipment (PPE) to their workers; (3) top management are not very concerned about safety and do not consider attending safety meetings important; and (4) systematic safety training is provided by few contractors. In Singapore, the main contractors on most projects often subcontract much of the work and, in turn, subcontractors also regularly subcontract their work to others, leading to the presence of many construction companies in one project, with problems of coordination and integration and finally negatively impacting safety [24]. In the United States, Hispanic workers, in general, have limited English language proficiency and lower education levels than other construction workers [25]. These workers usually take care of more hazardous jobs within the construction industry [25, 26]. Thus, they tolerate unsafe conditions more than others working on the construction site [25]. Furthermore, Hispanic workers are subjected to greater production pressure as well as impertinent attitudes and intimidation [25].

3. Research Method

- The construction industry is a hazardous work environment triggering many work injuries and fatalities. This research focuses on studying the safety performance and reasons for the high accident rate as well as hazard existence in the construction industry of Saudi Arabia. This research is designed to assist in understanding safety in the construction industry in an exploratory matter. Here, small- to medium-sized construction sites in the private sector are emphasized, where it is assumed that the lowest measures of safety guidelines and procedures are implemented. This research was conducted over three main stages: 1) literature review; 2) data collection and analysis; and 3) results and discussion. These stages were made to fulfill the following research objectives: 1. To examine the general status of safety performance in the construction industry of Saudi Arabia.2. To propose recommendations to improve safety performance in Saudi Arabia. Literature review was performed through several online databases, primarily Elsevier, ProQuest, and Google Scholar. This approach allowed the collection of a wide range of scientific research publications related to this topic. The data used in this research were collected by observations. Observation is considered to be a major data collection method when it comes to naturalistic or fieldwork locations [27]. It includes viewing people's actions in a systematic manner and record, analyze and explain their behavior [27]. Many studies in the field of construction safety used observation as a mean to collect data from construction sites through checklists [28-30]. For example, observation was used for data collection in a study that aimed to determine the risk factors that affect carpenters working in the construction sites [28]. Furthermore, observation was also used as part of data collection in a study in Thailand that aimed to measure the effectiveness of safety programs in enhancing safety performance in construction sites [29]. New opportunity for safety endorsement in the construction industry may result from the implementation of a systematic safety observation methodology [30]. A total of 100 random construction sites were visited by the author in the city of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, over a period of two months. The site visits were made in May and June of 2015 during construction working hours. The observational site visits mainly took the form of a safety audit with a checklist adopted from a number of checklists developed by several international organizations concerned with construction safety: the Occupation Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA), and Office of the Federal Safety Commissioner, Department of Employment, Australian Government [31-33]. After field data collection, data were analyzed by the use of Predictive Analytic Software (PASW) version 18. Quantitative analysis was conducted through descriptive statistics. Basic frequencies were calculated to help achieve the first objective of this research. The second objective was fulfilled by the conclusions and recommendations part of the paper, where recommendations to improve safety performance in Saudi Arabia are proposed by the author.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Construction Sites Classification

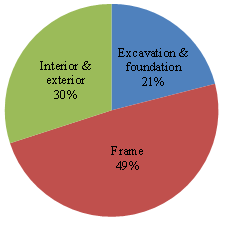

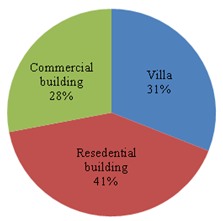

- To generate beneficial results regarding the safety conditions of construction sites, it was essential to acquire solid data from the site through observation and analyze these data by suitable tools. In this research, a sample of 100 random construction sites was the main source of data. Construction sites were classified in two ways: (A) construction lifecycle and (B) building type. In the construction lifecycle stage, there are three basic stages: excavation and foundation, frame, and interior and exterior. In terms of this classification, 21 construction sites were at the excavation and foundation stage, 49 sites were at the frame stage, and 30 construction sites were at the interior and exterior stage (see Figure 1). The majority of construction sites studied were at the frame stage, where the actual shape of building is made. In the building type classification, 41 construction sites were for residential buildings, 31 construction sites were for villas, and 28 construction sites were for commercial buildings (see Figure 2). Residential buildings represented the largest portion of the study sample.

| Figure 1. Construction lifecycle |

| Figure 2. Building type |

4.2. Current Construction Safety Status and Hazards

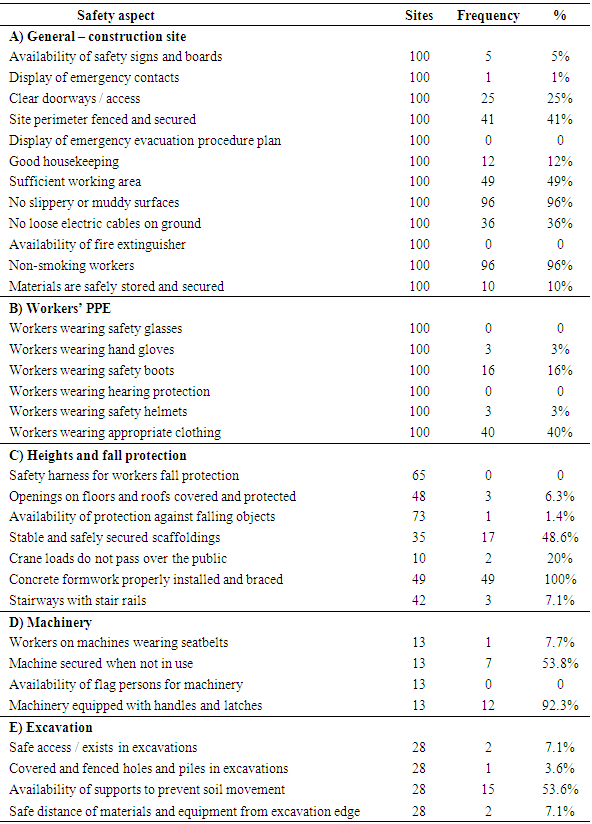

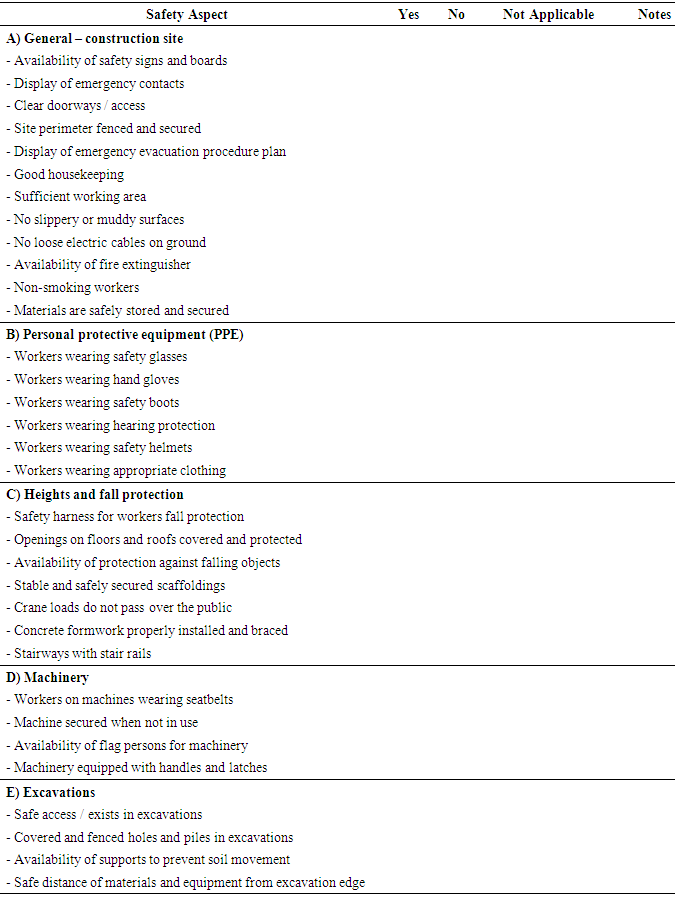

- The general status of safety hazards in the construction industry of Saudi Arabia was assessed by using a checklist which was filled during observation period. In addition to providing information on the actual safety conditions of construction sites, it also helped to identify the triggers of major accidents. The analysis results of the checklist are summarized in Table 1. Table 1 contains the safety aspects, sites applicable for each safety issue out of a total of 100 sites, frequency count, and total percentage. A total of 33 safety aspects are categorized under five groups: 1) general – construction site; 2) workers’ PPE; 3) heights and fall protection; 4) machinery; and 5) excavation. A limited number of construction sites shared all five safety aspects, due to the variety of construction sites visited. Therefore, not all safety aspects were applicable for all sites. Only the safety aspects grouped under general – construction site and workers PPE - were applicable to all 100 construction sites. The other three groups depended on the construction site lifecycle and building type. For instance, at the time of site visits, not all construction sites had machinery working on site or had excavation work. Thus, assessment was not applicable for these groups. The group with the least number of applicable sites was machinery, with only 13 applicable construction sites. In terms of the number of safety aspects in each group, general – construction site included 12 safety aspects, Workers’ PPE included six safety aspects, heights and fall protection included seven safety aspects, and both machinery and excavation included four safety aspects. In general, all groups showed a very poor safety record in construction sites. For example, six safety aspects did not exist in any construction site: display of emergency evacuation procedure plan, availability of fire extinguisher, workers wearing safety glasses, workers wearing hearing protection, safety harness for workers’ fall protection, and the availability of flag persons for machinery. The only four safety aspects with the highest positive impact were concrete formwork properly installed and braced at 100%, no slippery or muddy surfaces at 96%, non-smoking workers at 96%, and machinery equipped with handles and latches at 92.3%.

|

4.2.1. General – construction site

- In a safe construction site, the main contractor will be organized, a good planner, and effective in communication with all parties involved [10]. Workers believe that they are safe in construction sites [10]. On the other hand, these workers believe that owners, women, and children who are unfamiliar with construction sites are unsafe [10]. So, they are very confident that they can avoid accidents. When it comes to reality, their perception is wrong, as unsafe construction sites will be unsafe to all stakeholders involved. Experience might reduce the number of injuries and casualties, but not in all cases; circumstances may not always be in the workers’ favor. Two positive outcomes were foreseen from the analysis results under the general – construction site group of safety aspects illustrated in Table 1. Firstly, 96% of construction sites did not have slippery or muddy surfaces. The study took place during summer season, which might have contributed to the quick evaporation of water on site due to elevated temperatures, but, at the same time, the high percentage of sites with no slippery or muddy surfaces demonstrates the conserved use of water on sites. Secondly, just like the aforementioned safety aspect, 96% of construction sites did not have workers smoking on them during the site visits. This provides a good impression on non-smoking at construction sites. On the other hand, with respect to low-scoring safety aspects under this group and as shown in Table 1, a very limited number of construction sites displayed safety signs and emergency contact numbers. Safety sign boards are significant in construction sites, as they are a continuous reminder of important safety measures to be followed on construction sites. Moreover, none of the construction sites posted their emergency evacuation procedure plan. This is an indication that safety standards are not followed in the majority of construction sites and that it is not given a high priority by the project’s top management and owners. In terms of housekeeping, only 12% of construction sites showed a good record. This low percentage in the housekeeping of construction sites affected other safety aspects studied in this research, such as: (1) the presence of loose electric cables on the ground of 64% of construction sites, (2) only 25% of construction sites had clear doorways and access, (3) only 49% of construction sites had sufficient working area, and (4) 90% of construction sites did not safely store materials, storing their materials on adjacent streets or sidewalk. This sounds an alarm that construction sites can be very unsafe, especially for inexperienced individuals entering the site. In addition, storing materials outside of the construction site parameter will affect surrounding road traffic and pedestrians by invading their space and increasing hazard availability, resulting in accidents. Public access to construction sites was easy. Only 41% of construction site perimeters were fenced and secured, increasing the chances of accidents, especially with the bad housekeeping of the majority of these construction sites. Fire is a dangerous hazard at construction sites. Unfortunately, none of the 100 construction sites visited had a single fire extinguisher on it. This raises concerns regarding the safety measures implemented in the construction industry as a whole.

4.2.2. Workers’ PPE

- PPE is an essential component for workers’ safety on construction sites. A general universal safety measure in construction sites for all workers is to wear hardhats and steel-toed shoes [22]. These include PPE for the eyes, face, hands, and head and hearing protection [22]. Construction workers wear PPE, including safety glasses, hand gloves, safety boots, hear protection, safety helmets, and appropriate clothing, to protect themselves from the hazards surrounding them. Neglecting to use basic safety measures, such as PPE and checking behind the vehicle before reversing, accounts for 42% of accidents [26]. Table 1 shows an infrequent use of PPE by workers in construction sites. For example, safety glasses and hearing protection were not observably used by any worker at any construction site. Furthermore, hand gloves and safety helmets were used by a limited number of workers at few construction sites. Safety boots, which are essential at construction sites, were only observably worn by the majority of workers in 16% of construction sites. Many workers were wearing regular footwear, which provides very low protection at construction sites and are considered unsafe in construction environments. Finally, 40% of construction sites had workers wearing appropriate clothing. Thus, the majority of construction site workers had inappropriate clothing. This could be due to the fact that most workers in the Saudi Arabian construction industry are expatriates from Arabic and Asian countries and it is usual to see them wearing their own loose traditional clothing with no PPE. Therefore, the explanation for the increase in the number of accidents on construction sites becomes rational, specifically with minor accidents, such as hand and foot injuries.

4.2.3. Heights and Fall Protection

- During construction, many temporary structures are erected, such as scaffolds, formworks, shoring, ramps, platform, and earth retaining structures [34]. These temporary structures have contributed to a number of accidents in the construction industry by collapsing, workers falling from them, or objects falling from them onto workers underneath [34]. Key players in construction sites must have the knowledge, understanding, or at least awareness on the possible hazards of working with temporary structures [34]. This will help in making the construction work environment a much safer workplace. In the construction industry of Victoria, Australia, fall risks are considered an absolute priority for injury prevention [2]. This group of safety aspects focuses on high structures and the risks of falling for workers or objects. On the positive side, all construction sites with concrete formwork activities had properly installed and braced concrete formwork, which helps to avoid formwork collapse on workers and thus makes the construction site safer. On the other hand, none of the 65 applicable construction sites with workers working on structure edges had workers wearing safety harnesses. Thus, it is valid for the rate of injuries and death from height falls to be high in this industry in Saudi Arabia. Additionally, only 6.3% of construction sites with openings on floors and roofs had these openings covered and protected. Once again, adding to the high rate of injuries and deaths due to height falls, as many workers who are new to sites fall in these uncovered openings while working. Moreover, protection against falling objects due to workers working on structure edges was found in only one construction site out of 73 applicable sites, representing 1.4% of the sample. This represents a great risk to the public living in the surroundings of the construction site or passing by it. Adding to public risk is the high number of cranes that passes over their space with loads that represent a hazard if not safely secured. Out of 10 construction sites with cranes, just two did not pass over the public space. Cranes with loads passed over pedestrian footpaths, streets, and adjacent buildings. In one case, a tower crane regularly passed over a neighboring fuel station. With respect to stairways inside incomplete structures, 7.1% of applicable construction sites had stair rails for stairways, which increases the chances of falling due to tripping. Scaffoldings were used in 35 construction sites during the sites’ observation period. 48.6% of these scaffoldings were stable and safely secured. The remainder either had broken components in them or bad joint connections. The use of these damaged scaffoldings represented a dangerous hazard for workers and the passing public. In certain cases, the damage on scaffolding elements was very clear, yet workers continued their work.

4.2.4. Machinery

- Construction machinery assists in moving materials and loads within the construction site. When unsafely operated, they could cause severe injuries to workers at the construction site. Thus, they provide a hazardous work environment for all workers involved in their operations but simultaneously provide efficiency and speed in construction projects [12]. The main heavy equipment workers are vehicle operators and flaggers, who are co-operators to help operators in the construction site by using gestures, signs, or flags [12]. The presence of flaggers on construction sites is important to help vehicle operators’ work more efficiently, finish the job faster, and implement safety rules [12]. In this research study, 13 construction sites out of 100 had machinery operating in them. In 12 of these construction sites, machinery were equipped with handles and latches, which provide easy access to operators in addition to stability inside the machinery. In almost half of the construction sites, machinery were secured when not in use. So, in seven construction sites, machinery were parked properly away from hazard sources in safe areas. The rest of the machinery in construction sites were parked almost at any location, with some located near steep excavations. Generally, seatbelts within construction sites were not used by operators. It was only observably used by operators in one construction site. This is because seatbelt use is not enforced by law inside private property and because there were no safety officers or concerned construction managers. Although flag persons are important for directing operators within the construction site efficiently and quickly, none of the construction sites had any flag persons on the job. This is most likely because flag persons are generally seen as an extra cost with limited output.

4.2.5. Excavation

- Excavation is made so work can proceed with underground structures, such as building foundations and water storage tanks. In this group of safety aspects, the focus was on the assessment of safety measures in excavation. Overall, the analysis results show a lack of safety precautions in most construction sites with excavations. For instance, excavations should be supported from all sides to prevent soil movement, but this was the case in only 53.6% of applicable construction sites. The rest of the construction sites either lacked soil supports or had soil supports on certain locations, increasing the probability of soil movement and collapse hazards. Furthermore, safe access into excavations and exist out of excavations were found in only two out of 28 construction sites. This makes the process of evacuation during emergencies more complicated. Similarly, two construction sites provided safe distance to materials and equipment from excavations, and 26 sites did not provide the same safe distance. Thus, it becomes very likely for materials and equipments to fall into the excavation when handled or moved in a wrong way. Moreover, only one construction site had excavation holes and piles covered and fenced. Here, the likelihood of injuring inexperienced workers is increased. These results reveal the existence of many hazards in excavations of construction sites and a need to manage these hazards for the safety of workers and temporary visitors.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- This research investigated the safety performance of the construction industry in Saudi Arabia, focusing on small- to medium-sized construction projects in the private sector. The main source of data was a series of 100 construction site visits. Generally, the construction industry has a low safety performance due to the existence of many hazards on the work site. Concern was given to five groups of safety aspects. A few positive safety aspects were found in construction sites, all different safety aspect groups showed low safety performance, with an urgent need for significant improvement in safety practices. Out of the 33 safety aspects explored in this research, six were not observed in any of the 100 construction sites studied: (1) display of emergency evacuation procedure plan; (2) availability of fire extinguisher; (3) workers wearing safety glasses; (4) workers wearing hearing protection; (5) safety harness for workers’ fall protection; and (6) availability of flag persons for machinery. The fact that these safety aspects were not used or seen in construction sites reflects the general negligence of construction managers and project owners in terms of safety considerations. A number of safety aspects of great importance among the five safety aspect groups had limited presence in the Saudi construction industry. For instance, under general – construction site group, safety signs and boards along with display of emergency contacts were seldom present in construction sites. Moreover, good housekeeping was also not practiced in a healthy manner, causing issues and hazards on sites and leading to not having clear door access, sufficient work areas, and appropriate locations for material storage. Loose electric cables were also found on the ground of many construction sites, forming a dangerous hazard on site. Additionally, fences to secure site parameters were used in less than half of the construction sites, allowing anyone to enter at their will and get exposed to the potential hazards within. Safety aspects related to workers’ PPE demonstrated the wide lack of PPE use by construction workers in the industry. In the heights and fall protection safety aspect group, protection and guarding of openings and edges were available in few construction sites. Furthermore, almost half of the scaffoldings used in the visited construction sites had damaged elements, with the potential to collapse. Moreover, cranes observably passed over the public in many locations, exposing them to the hazard of load falling. Workers tripping and falling due to the unavailability of stair rails was also very much possible, as only a limited number of construction sites had installed temporary stair rails. The safety aspects group of machinery revealed that the majority of machinery operators tended not to wear safety seatbelts when working on site. This was due to the unavailability of rules that forces the use of seatbelts inside the parameter of a private construction site. Furthermore, machinery were not parked in a secure space when not in use in almost half of the applicable construction sites. Under the excavation safety aspects group, a very limited number of applicable construction sites had safe access to the excavation, with materials and equipments stored a safe distance away from the excavation edge. Furthermore, holes and piles in the excavations were not covered or fenced except for one applicable construction site. Additionally, adequate support to prevent soil movement was only found in half of the applicable construction sites. In order to improve the safety performance of the construction industry in Saudi Arabia, different stakeholders must give priority and weight to safety practices. Initiation of safety awareness and implementation of policies can start from the government level. The private sector should also be accountable for safety deficiencies in construction sites. The author proposes the following recommendations for the enhancement of safety performance in the construction industry of Saudi Arabia:● Set safety manuals, procedures, and guidelines for the construction industry enforceable by law,● The establishment of a dedicated body that works on inspecting and monitoring construction sites and enforcing safety law,● Owners and contractors showing negligence of safety measures in construction sites should be held accountable for not sustaining a safe working environment in their construction site, ● Conduct meetings and workshops involving different construction stakeholders to discuss issues related to construction safety, ● Promote the implementation of safety practices throughout the lifecycle of buildings and structures, ● Provide safety training courses by recognized institutions to develop professional personnel skills, ● Impose the presence of qualified safety personnel with a qualification or basic training on safety for every construction project, ● Conduct and publish research on safety and make it available to the public,● Address the current safety issues in the construction industry and develop strategic plans to address them.A possible limitation of this research is that the study was carried out during the summer season and not throughout the year. This could have an effect on some of the results related to the use of PPE in construction sites. With high summer temperatures, some workers might have neglected the use of PPE to cope with the heat.More research in the field of construction safety is needed in Saudi Arabia. Future research could include measuring the safety performance of public construction projects and perhaps conducting a comparison study between public and private sectors.

Appendix

- Study Checklist 1. Demographic questions (Place a circle):

2. Construction safety performance (Place a tick):

2. Construction safety performance (Place a tick):

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML