-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2015; 4(4): 128-148

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20150404.04

Effects of Organization Structures on International Construction Joint Venture Risks

Apichart Prasitsom, Veerasak Likhitruangsilp

Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

Correspondence to: Veerasak Likhitruangsilp, Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

In the construction industry, international construction joint venture (ICJV) is a common form of cooperative strategy, which is adopted by contractors (as partners) for executing large construction projects that require a large amount of resource beyond the capacity of a single contractor. While partners establish an ICJV to enhance their capacities and competiveness as well as to achieve their objectives, ICJV management encounters a variety of risks throughout project life cycle. There are many factors contributing to the risk parameters, namely, consequence and likelihood. An important factor is the ICJV organization structure, which can be grouped into two types: the collaborated governance structure (CG-JV) and the separated governance structure (SG-JV). This paper aims to identify and analyze critical risks during the construction phase of ICJVs by integrating the Delphi technique into the survey and interview process. The results show that there is a statistically significant difference in both risk parameters of the CG-JV and the SG-JV. This is clearly present in the internal risk category, such as the difference on resource allocation between partners and the improper intervention by partners. The ICJV partners can use the outcomes to prepare their comprehensive risk management plans which correspond to the types of ICJV organization structure that they have chosen.

Keywords: Joint venture, Organization structure, Risk management, Non-Parametric statistic, Hypothesis test

Cite this paper: Apichart Prasitsom, Veerasak Likhitruangsilp, Effects of Organization Structures on International Construction Joint Venture Risks, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 4 No. 4, 2015, pp. 128-148. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20150404.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Due to limited resources, experience, and technology of a single construction contractor, joint ventures (JVs) are usually formed for large engineering projects worldwide [30]. For international construction joint ventures (ICJVs), the partners entail local and foreign contractors, which collaborate together to overcome their individual limitations, maximize project performances, and achieve the objectives of each partner, including earning profit, learning know-how, and initiating partnership [4, 24, 33]. In addition, the partners share profit, loss, and liability per their proportions of contribution [29].Although ICJVs have been adopted in many large construction projects for decades, their success rate was quite low [14, 30, 34]. In many projects, each partner did not achieve their expected objectives. To address such problems, there have been efforts to integrate risk management to ICJV management. Several research works shared a common concept to enhance ICJV performances, but they focused on different specific aspects. For example, Bing et al. [4] and Shen et al. [42] aimed to identify the sources of risks and understand the risk impacts. In their works, risks were categorized into three and six groups, respectively. Similarly, Kumaraswamy [27] identified risks by considering the cooperation between the partners throughout project life cycle. Seneviratne and Ranasinghe [40] assessed risk by focusing only on the financial aspect of ICJV in mega transportation projects. The structural equation method (SEM) was adopted to express the relations between risks and ICJV performances [30]. Zhang and Zou [47] introduced the analytical hierarchy process (AHP) and fuzzy logic to evaluate CJV risks. Zhao et al. [48] focused on the effects of contractor capability (e.g., company nationality, size and experience) on risks. Although these research works have focused on various aspects to enhance ICJV performances, there is an important issue that has been limitedly investigated, that is the ICJV organization structure. The ICJV organization structure represents the relation among various tasks between partners such as allocation, communication, coordination, and supervision, all of which have a direct impact on the achievement of the ICJV objectives [36]. Julian [24] and Ozorhon [31, 33] mentioned that this factor plays a major role in many dimensions of ICJV performances. In addition, Sillars and Kangari [41] commented that the success of a project-based joint venture related to the alliance organization structure designed by partners. Two important parameters of the ICJV organization structures that affect the risk management process are [5, 18]: 1. The level of task responsibility and liability of each partner2. The level of communication and coordination beyond between partners.Different ICJV organization structures should therefore affect the values of two basic risk parameters [26, 38]: consequence (CSQ), which is the impact of risk events [21, 43], and likelihood (LLH), which is the chance of a risk occurring within a defined time period [21, 43].

2. Objectives and Scope

- The main objective of this paper is to examine effects of two main forms of the ICJV organization structure, namely, the collaborated governance structure (CG-JV) and the separate governance (SG-JV), on the risk parameters. A hypothesis of this study was set as follows.“For a certain ICJV risk, the values of CSQ and LLH should be different for different forms of the ICJV organization structure.” Due to a limited sample size and data contribution, a nonparametric statistical method was used to test this hypothesis.In addition to such main objective, minor objectives are1. To identify and assess critical ICJV risks associated with ICJVs in Thailand in the construction phase2. To propose risk-responsive measures for such ICJV risks during construction3. To analyse the influence of ICJV organization structures on the consequence (CSQ) and likelihood (LLH) of the ICJV risks during construction.The ICJV management can be constructed based on the concept of ICJV life cycle, which is divided into five phases: (1) the formation phase, (2) the bidding phase, (3) the construction phase, (4) the warranty phase, and (5) the termination phase [37]. Each phase entails its unique objectives, which can affect the performance in subsequent phases. Thus, the number of ICJV risks and their parameters for different phases should be different [29, 38]. In this paper, the ICJV risks, which are identified and analysed in accordance with the three minor objectives, are the set of risks that could impact any performances of ICJVs during construction only.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Organization Structure of ICJV

- The organization structure is an internal official operation plan for a project or a company, which will be used as a guideline for its governance [3]. The organization structure of each ICJV is quite unique and is characterized by a number of partners, proportion of contribution, and task proportion [36]. However, the difference among ICJVs did not make their organization structures diverse much [38]. Most of the ICJVs shared common structures, which can be categorized into three forms: the CG-JV, the SG-JV, and the mixed organization structure, which is just the combination of the first two types [26, 41]. This paper focuses on the CG-JV and the SG-JV only.

3.1.1. Cooperative Governance Joint Venture (CG-JV)

- For the CG-JV, all tasks in a construction project are handled by a collaborative team, which consists of the personnel from each partner or from outsourcing [46]. This team is led by a main project manager, who is under the supervision of the executive board of the ICVJ. No task is allocated to an individual partner [36]. The unique characteristics of the collaborated-operation structure are as follows [38].1. The partners participate in any operations of the construction project via the ICVJ executive board only. 2. The ICVJ executive board and the main project manager are fully responsible for every task.3. The main project manager of the ICVJ has no relationship with any partners and is hired to carry out all tasks in the construction project.4. All staff members of the ICVJ, who are nominated by each partner or outsourced, are required to be under the supervision of the main project manager and must take no direct order from any partner.5. The capital money for the entire construction project is directly obtained from the ICVJ’s fund, not from an individual partner.6. The ICVJ’s net profit or loss is determined by the overall performance of the construction project and is allotted to each partner based on its proportion of contribution.7. The partners are jointly and severally liable for obligations to the project owner and the third person, and share their liability pursuant to their proportions of contribution.The CG-JVs has not been popular in the Thai construction industry due to its high cost and the complexity of its formation and management [37]. According to some ICVJ executives, this structure was however used in some ICVJ projects due to the difficulty of dividing construction tasks into portions [38].

3.1.2. Separate Governance Joint Venture (SG-JV)

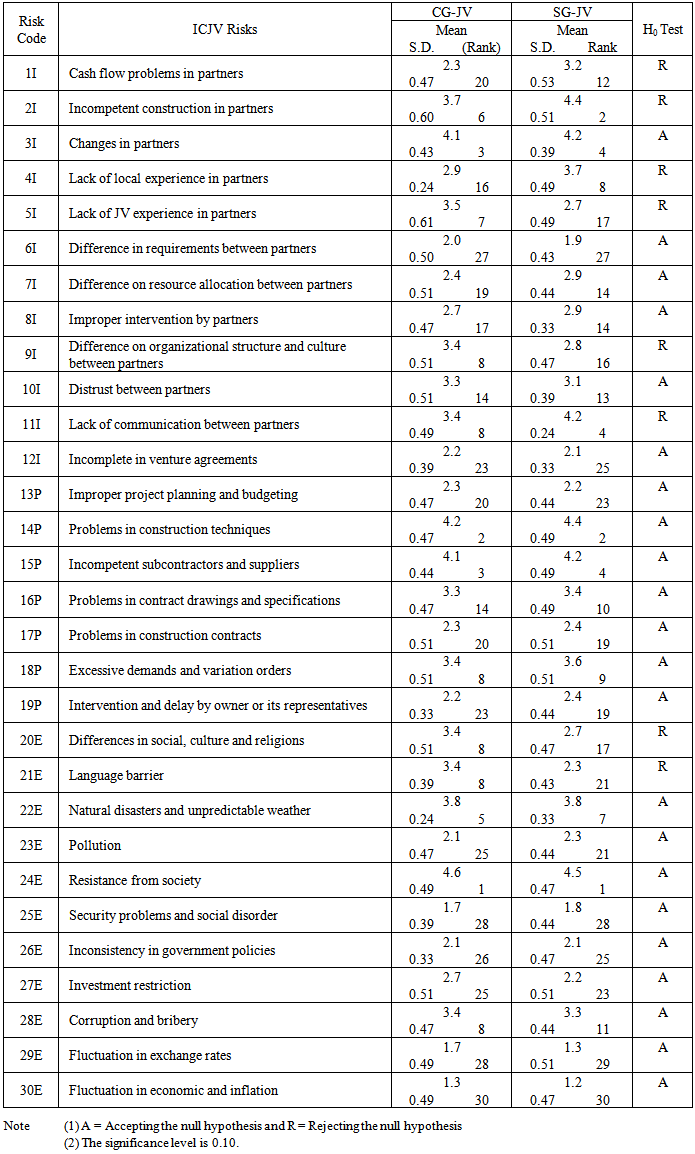

- All tasks of the SG-JV are grouped into work packages, each of which is executed by a certain partner [38]. Typically, no work package will be handled by multiple partners at the same time [36]. Each work package is carried out by a project manager nominated by the partner that is responsible for that package [26]. All project managers limitedly coordinate with the main project managers and the ICVJ executive board [41]. The unique characteristics of the SG-JV are as follows [38].1. Each partner has a full control over its work packages.2. The ICVJ executive board and the main project manager have less authority than those in the CG-JV.3. The main project manager is responsible for such tasks as the overall image of the construction project, communication with the owner and the third person, and coordination among other project managers.4. The project manager and personnel of each work package are appointed by a partner that handles that work package and are responsible for their work package only.5. Each partner must be responsible for the capital money of its work packages. However, there are some work packages (e.g., general affairs) that are normally funded by the ICVJ’s capital money.6. The profit and loss of each partner is evaluated based on the performance of its work packages only.7. The partners are jointly and severally liable for obligations to the project owner and the third person for every task, and share their liability pursuant to their proportions of contribution.Table 1 compares unique characteristics between the CG-JV and the SG-JV. As can be seen, each ICJV structure has its own governance style [46]. While the CG-JV is similar to partnering as a new organization, the SG-JV is just a loose cooperation, in which each partner can operate independently [26, 38]. However, both structures share a similar important characteristic that is sharing liability for the owner and the third party among the partners [29].

| Table 1. Characteristics of different ICJV organization structures |

3.2. Previous Studies in the ICJV Management

- To understand the underlying concepts for managing ICJVs, two main issues concerning ICJV were reviewed, which are ICJV risk management and ICJV performance management.

3.2.1. ICJV Risk Management

- Risk management is a principle which uses analysis and evaluation to reflect an opportunity and impact from a variety of factors, which may affect the expected project operation performance. Each organization needs improvement, strategies, and policies to reduce chances and effects of their risks. The principle of risk management has also be applied to ICJV management. Kumaraswamy [27] originally invesitgated risk management in ICJVs. He focused on the appraisal and apportionment of ICJV project risks to all partners. He would like to determine the balance between each partner which keeps partners working together. From this study, criteria, sub criteria and indicators of risk evaluation and allocation have been mentioned and studied. He proposes idea about risk allocation among partners. Two years after that, Bing and his team have also studied about risk of CJV by considering overall risk of the whole project. The study starts from identifying and evaluating each risk involved in CJV. Those risks are divided into three main groups, they are; Internal Risks, Project-Specific Risks and External Risks [4]. A study after that emphasizes mainly on presenting idea about Risk Management Model for ICJV which can also be divided into three main parts which are identification, analysis and treatment. Three case studies are considered based on the structure of this model [3]. Risk evaluation by three groups of factor, done by Bing and team, has become prototype which is mainly used for references in other studies about risk assessment of CJV which are done later. Shen et al. [42] is another group who study about identifying and evaluating risks of CJV but they divide risks into six groups which are financial risk, legal risk, management risk, market risk, policy and political risk and Technical risk. All of these six groups have different risks with different level of impact. Mohamed [30] also studies about the relationship of risks that influences performance of ICJV through analysis done with SEM technique. Although the study doesn’t dig down deep enough to evaluation of each risk, it is the only study that shows relationship between risks and performance factors. In 2007, Zhang and Zou [47] try to improve effectiveness for CJV’s risks evaluation by applying fuzzy logic and analytical hierarchy process (AHP) technique with data collection in Likert scale to reduce defection done by judgment of people who answer questionnaires. This study is done by using information of Risks, done by Bing and team in 1999, as its foundation.

3.2.2. Viewpoint on Performance Management

- Performance management is any process (e.g. considering, evaluating, adjusting and tracing) required which help company to achieve its target goal. “The goal is accomplished” carries the same meaning with “Successful Company”. Most of the time, they are mentioned as the same within several articles which do not focus directly on performance management or strategic management. For those studies which have applied principles of performance management to evaluate CJV, Ozorhon and his team are considered as the leader in this field. Their articles regarding study of CJV’s performance have been published in 4 journals from 2007 to 2010 [31-34]. Ozorhon and his team start their study by proposing model which can be used to predict CJV’s performance [34] by using technique which is called as analytical network process (ANP) to help in analyzing complex and linked relationship between factors and CJV’s performance. This model mainly emphasize on relationship between CJV’s performance and factors in four groups. They are JV Structural Factors, Interpartner Fit, Interpartner Relations, and External Factors. In last stage of study using this model, several important factors like Conflict resolution, Effectiveness of control, Cultural fit, Contract, Trust and Strategic fit have been mentioned as influencing factors. After applying this model to the real construction project, the result shows range of difference between evaluated performance from the model and actual performance at the lowest 1.68% and the highest at 23.30%. Following year, Ozorhon and his team pick up issues about Interpartner Fit and Interpartner Relations which are two groups of factor mentioned in above model and study thoroughly. They try to find influences of Partner Fit over CJV Performance [31]. They divide Partner Fit’s consideration into three aspects which are Strategic Fit, Organizational Fit and Cultural Fit. In their study, in order to find relationship between each factor, the technique known as structural equation modelling (SEM) is used. The result proves that Strategic Fit has direct influence on Interpartner Relations while organizational Fit and Interpartner Relations also have direct influence on CJV Performance. It is surprising to learn that Cultural Fit has no direct influences to none. Moreover, this study is the beginning of adding new perspectives into CJV performance which are divided as “project performance” and “performance of IJV management.” As the result of study has shown abnormality of Cultural Fit, Ozorhon and his team, within following year, decide to study about each factor into more details. They pick Cultural Fit, which is one of three factors in Partner Fit, as the main target for analysis in order to find its relationship with project performance in clearer picture. They split issues regarding Cultural Fit into three main parts which National culture, Organizational Culture and Host Country Culture. Through SEM technique again, the result shows that Organizational Culture is the only factor which directly influence CJV Performance [32]. In year 2010, Ozorhon and his team reconsider about the model for CJV’s performance evaluation [33] by showing the result of the study to propose idea in separating aspects of CJV’s performance evaluation into four aspects which are the performance of the project, the IJV partners, the IJV organization itself and the perceptions of the IJV partners. They also study about the relationship of these four aspects with all groups of factor through SEM analyzing technique again. Apart from Ozorhon and his team’s studies, Mohamed [30] is also another one who studies about performance of CJV through learning relationship between CJV’s risk, success factors and performance through SEM technique. He classifies relating factors into six groups which are Partner, Task, Formation, Government, Operation and Project. He finds that partner and task are two groups of factor which have direct influence over Formation while Formation has also direct influence on Operation. Sillars and Kangari [41] also propose study from different point. They focus on how successful each partner is from CJV’s operation instead of seeing overall success of CJV. They use “Organization return” and “Market position change” as indicators for each partner’s success. From result of study, smaller-sized partners tend to be more successful in both financial and growth aspect when compared to larger size partners. Moreover, the study also shows that culture compatibility is also supporting factors for partners’ success.

4. Research Methodology

- To accomplish the objective of this paper, the Delphi technique and the nonparametric statistic test were integrated into the data collection process to enhance the reliability of results [1, 9]. With the many rounds of survey required by the Delphi technique, the research was taken during 2012 to 2013.

4.1. ICJV Risk Identification

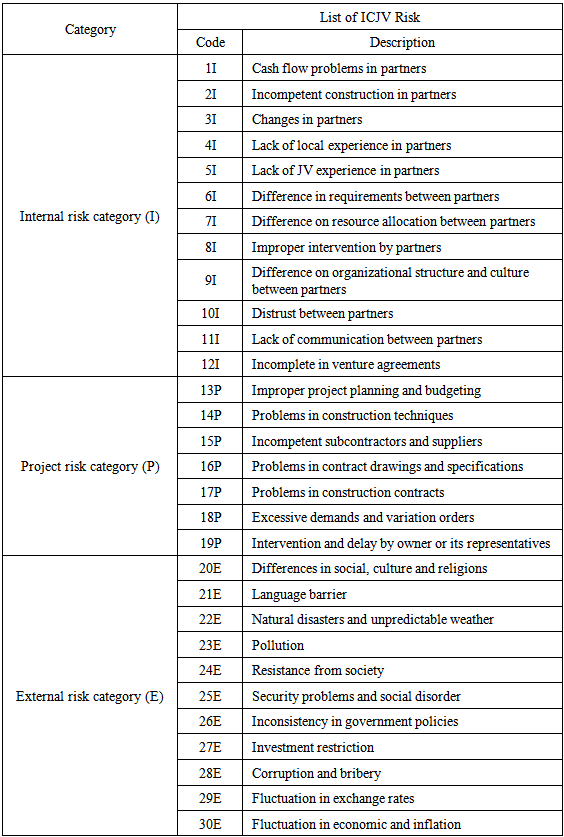

- After reviewing literature on ICJVs by focusing ICJV risks during the construction phase, 75 ICJV risks were drafted. To justify the suitability of these ICJV risks for Thai construction industry,A pilot survey was conducted in November 2011 by conducting in-depth interviews five project managers, each of which has been involved in at least five ICJV projects in Thailand, to validate basic information and hypotheses. This pilot survey confirmed a total of 30 ICJV risks, for the construction phase, of ICJVs in Thailand, which were grouped into three categories: Internal risk category (I) (with 12 ICJV risks), Project risk category (P) (with 7 ICJV risks) and External risk category (E) (with 12 ICJV risks), as shown in Table 2.

|

4.2. Identifying Management Objectives of an ICJV in the Construction Phase

- The objectives of ICJVs in each phase of the project are diverse [37]. The main objectives in the construction phase of an ICJV are quite similar to those of typical construction projects, which is the project should be finished on time, under the budget and with good quality [3, 39]. However, individual ICJV partners also want to achieve their objectives such as technology and know-how transfer, new market penetration, and creating partnership [24]. Both main and individual objectives are important, but with different significance levels. Kumaraswamy [27] reported that individual objectives were greatly important at the beginning of an ICJV and became less important during the construction phase. The partners had to focus on the main objectives first because failing these objectives may have a fatal impact on the profit and reputation of the ICJV as a whole as well as the partners [35]. To collect the data of consequence (CSQ) of each ICJV risk for three aspects, it is a huge task at the same time. This study decided to collect the CSQ for all ICJV risks on the cost constraint and the schedule constraint. Because the data for both constraints is more cohesive than another [37]. The example of the cost of the construction operations can varies based on several ICJV risk events which are; 1. For construction tasks, there are increasing more work to finish, rising in cost of needed resources and being responsible for other partner’s expense.2. For administration tasks, there are increasing work than plan, wasting time on some issues longer than anticipate, increasing in price of needed resources, paying fine, paying compensation, losing expected interest, paying higher interest than expectation and being responsible for other partner’s expense. The example of schedule for construction operations, it may be varied based on several circumstances which are; 1. For construction tasks, there are more tasks to do, tasks is halted or stopped, and tasks cannot reach expected goal. 2. For administration tasks, there are slow in cooperation, delay in document works, and in decision making process.

4.3. Questionnaire Design

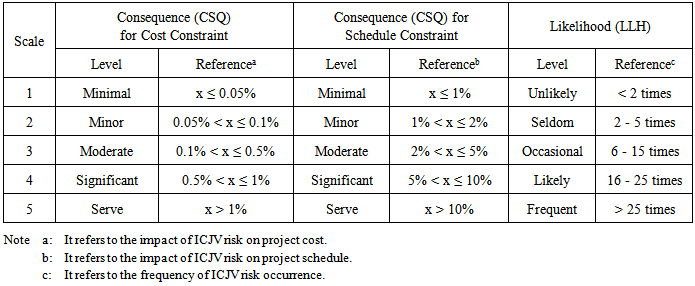

- The questionnaire used in the data survey was divided into three parts. The first part was the introduction for acquiring basic information of respondents who are the professional group is engineers who have the work experiences in two or more ICJVs in Thailand. The second part contained the questions regarding their past projects to know the ICJV organization structures in which they used to work. In the last part, the respondents were asked to evaluate two risk parameters for each ICJV risk: consequence (CSQ) and likelihood (LLH) [43]. In this survey, the respondents were requested to assess the CSQ values on the cost constraint and the schedule constraint, whereas the LLH for both constraints was assumed to be not much different [37]. So, the respondents were requested to assess a value of LLH. The five-point Likert scale was used for this risk evaluation process [16, 43], the details are presented in Table 3.

|

4.3.1. Cost Constraint

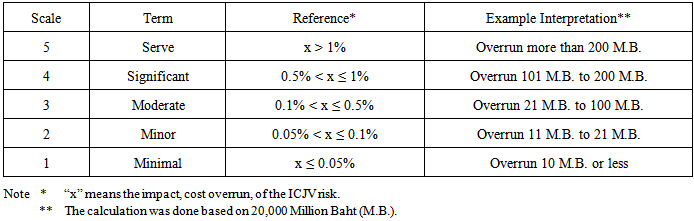

- Although ICJVs has mostly the contract value of more than 10 billion baht (mostly around 30 – 60 Billion Baht), in reality, the real budget for project operation is much lower [35]. The rising in cost reduces the expected profit [40]. In term of business, losing more than one million baht from expected amount is considered big mistake [24]. Table 4 indicates the sets of the five point Likert scale for CSQ of cost constraint. The reason why proportion of cost is affected only a little (Scale 5 is just more than 1%) is because the study assume to consider each ICJV risk separately. So in reality, if there are effects created by several ICJV risks altogether, overall effect value will be higher than 1%.

|

4.3.2. Schedule Constraint

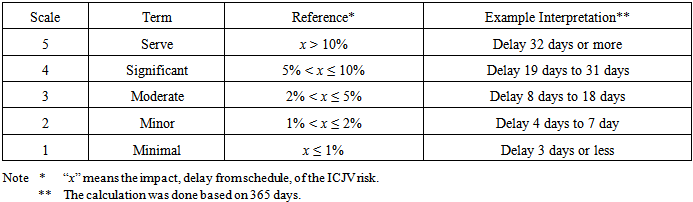

- The delaying from the construction schedule comes with paying fine which also affects cost in another way [3]. Although ICJVs takes long time to finish but the schedule is very tight [24]. A few months delay can create serious effect toward ICJVs [3, 34]. Table 5 shows the sets of the five point Likert scale for CSQ of schedule constraint.

|

4.3.3. Frequency Formats and LLH

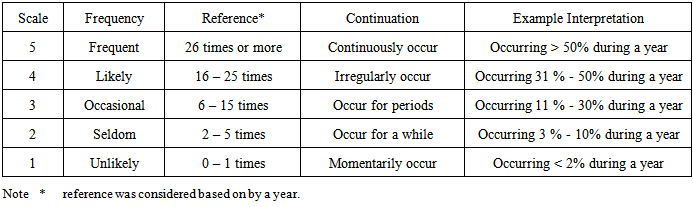

- The duration of construction period of each ICJV usually is vary [4]. Mostly, it can take around two to six years [29]. So, one value of frequency may be less for a long operation of ICJV but it may be more for a short operation of ICJV [47]. To eliminate this problem and to compare every ICJVs at the same time, the evaluation of frequency at construction phase would use the consideration based on each year of ICJV operation, as shown in Table 6.

|

4.4. Survey and Data Evaluation

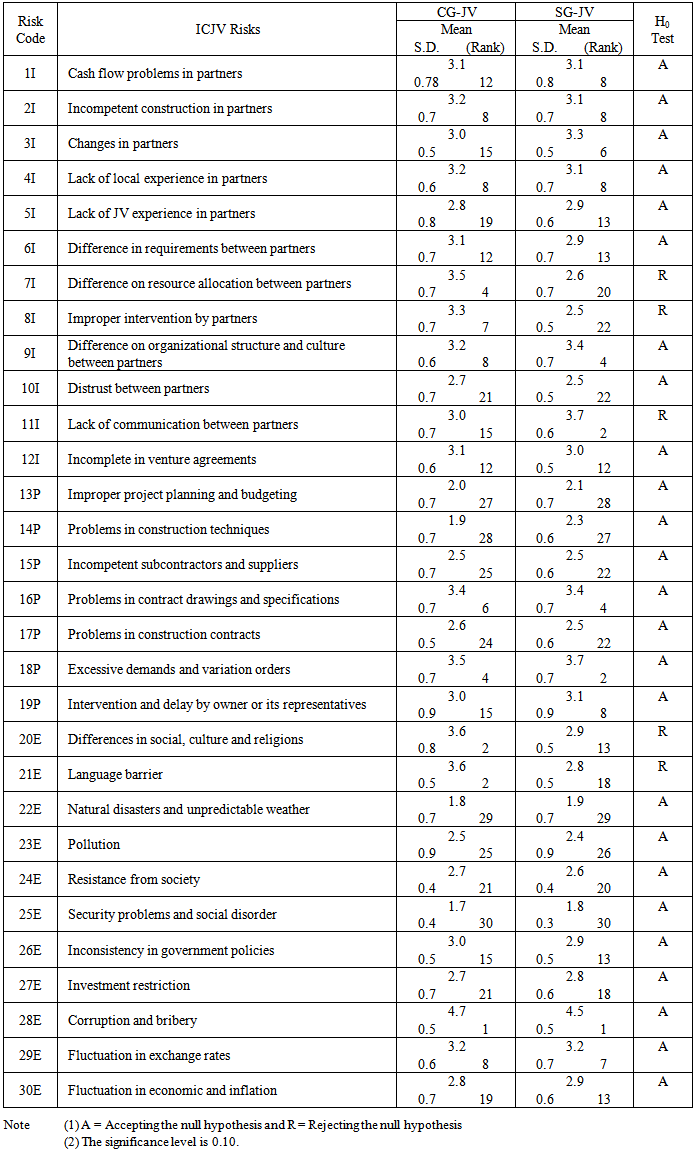

- The process began with the questionnaire survey and in-depth interview with respondents in the professional group who are engineers of officers in the management level with experiences in two or more ICJVs in Thailand. They would give the answers and opinions for risk parameter, including consequence (CSQ) and likelihood (LLH), by considered the work experience in the past. This step processes were separated into two parts including (1) the part of data survey and (2) the part of data analysis, as shown in Figure 1 [17, 20, 25].

| Figure 1. Process of Data Evaluation by Delphi technique |

4.4.1. Part of Data Survey

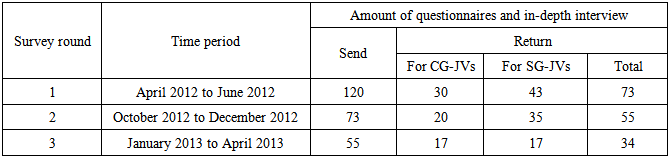

- The data collection process for each respondent in the professional group would be happened more than 1 time but not more than three times [9, 20]. Each round had the different purposed and the different questionnaire [25].1. The first roundDuring April to June 2012, the 120 copies of first questionnaire of ICJV risks was created for letting the professional group to evaluate CSQs and LLHs for 30 ICJV risks. The format of distributing questionnaires and interviews was direct deep interview with each respondent in the group. The main purpose for this round is to collect primary data of CSQs and LLHs as well as opinions about managing ICJV risks in Thailand. In the end, the 55 copies of questionnaires for ICJV risks for the construction phase were returned. By statistical analysis in the part of data analysis, it was found that all values of standard deviation for all CSQs and LLHs are higher than 1.50.2. The second roundFor collecting the data in this round, there are two contents as the main purposes for the second questionnaire of ICJV risks, as follows:- The content to propose the overview results from the first round. So, respondents could consider the overall values of CSQ and LLH for 30 ICJV risks and propose comments.- The content to ask each respondent to confirm or change his or her data, which is values of CSQ and LLH, from the first round. The questions would focus on data which each respondent had different opinions from the overall results. In October 2012, each respondent in the professional group, who were only the person participating the first questionnaire, received the one set of the second questionnaire of ICJV risks but each questionnaire had the different details. That was the first content in all questionnaires was same but the details in the second content would depend on the answer of each engineer from the first round. Until December 2012, there were 55 respondents being participants for the second round of data survey and in-depth interview. It was found that the standard deviation of CSQs and LLHs for 18 ICJV risks are lower than 1.00. Moreover, the standard deviation scores of 9 risks are equal to or lower than 0.60.3. The Third RoundAs for the data collection in the third round, the third questionnaire of ICJV risks had the contents and the distribution like as the second round. The purpose of the final round is that the respondents confirmed or made final decisions for CSQ and LLH values. In addition, the amount of questions in the second content were decreased a lot. Only ICJV risks, which their standard deviation of CSQs or LLH still higher than 1.00, were focused. Finally, the only 34 respondents were in this round which occurred during February 2013 to April 2013. Moreover, it was found that all values of standard deviation for all CSQs and LLHs are equal or lower than 0.70.

4.4.2. Part of Data Analysis

- Because there were three rounds of the part of data collection, there had to be three rounds for the part of data analysis, as well. The analysis of results for each round separated the calculation process into 2 parts as follows [20, 25]:1. Finding of the measures of central tendency, being mean, to analyse the averages of data In this paper, mean of CSQs and LLHs for an ICJV risk would be calculated three times with the different populations. They were the whole population, the CG-JV population and the SG-JV population.2. Finding of the standard deviation and the consensus values to analyse the data consistencyThe calculation for consensus value started from consideration of the frequency of each scale on how many percent of the total population and then choose the frequency with the most percentage as consensus value. The criteria to be used in considering that the data were consistent, the consensus values must be more than or equal to 70 percent after result analysis in the third round. If an ICJV risk still had the consensus value for the risk parameter, CSQ or LLH, less than 70%, it was considered that the ICJV risk must find the reason to support that why could not it find the consistency with information.

4.5. Determining the Level of Risk

- The level of risk (LOR), which means the magnitude of a risk, for a certain ICJV risk is the product of consequence (CSQ) and likelihood (LLH) [21, 22].

5. Survey Results

- The survey with applying the Delphi technique was repeated three times until the consensus of data emerged [17]. As the results, there were 34 respondents, who have two or more experienced in ICJVs in Thailand, as the sample size. Moreover, the number of respondents, who have experienced in the CG-JVs and the SG-JVs, are distributed equally, 17 per each. Table 7 indicate the details of each round.

|

6. Hypothesis Test

6.1. Choosing Statistical Tool

- It is necessary to test the hypothesis of paper, which states that the CSQ and CSQ values of an ICJV risk in a certain phase are different for different ICJV organization structures. By the literature review, there are many possible methods to test the hypothesis of a study from simple approaches with low reliability to complex approaches with high reliability [9, 16].In general, these methods are divided into two different theories [2, 19]: 1. The parametric statistic test 2. The nonparametric statistic test. The first theory entails more reliable statistic methods with difficult calculation processes [28]. It also requires complete and restricted information about the population such as the size and the type of distribution [2]. When the population or sample are not perfect due to the limit of population size or the shape of distributed data, the hypothesis should be tested by nonparametric statistic testing methods [1, 45]. The calculation process of this theory is simpler than that of parametric statistic tests, but its reliability is less. The nonparametric methods are a more popular tool because it is usually challenging to set perfect assumptions for the population or sample for the studies.In this paper, the nonparametric statistic test was chosen as the main tool for testing the hypothesis. The reasons to apply the nonparametric test are:1. The size of sample is 34 respondents in the total. There are 17 cases in each group of the sample, being the CG-JVs group and the SG-JVs group. This amount is considered as the small-medium sample size [2, 44, 45]. 2. By applying the Delphi technique to survey process, the samples was not random according to the statistic theory [7, 20, 25].3. All data are in the format of the ordinal scale [12] and are not the normal distribution [11, 23, 25].Form existing methods in this type of statistic test, with the format groups of sample, the sample size and type of data, therefore, this study decided to the Mann–Whitney U for the processes of data analysis [23]. The efficiency of this tool are accept that is close as the t-test on the normal distribution [7 23, 44].

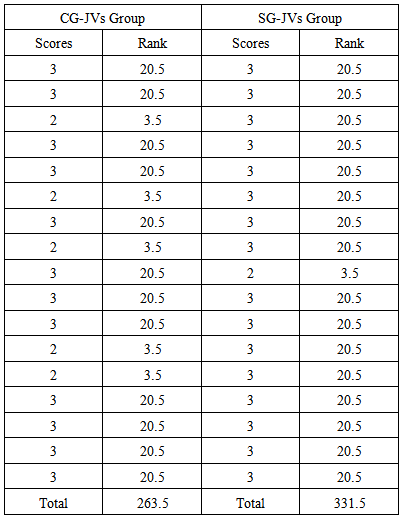

6.2. Process of the Mann–Whitney U test

- The Mann–Whitney U test is the method to compare whether the data distributions of the independent groups of the sample would be differ. Because the concepts of the Mann–Whitney U are close as the t-test or ANOVA in the parametric statistic test, many researchers mentioned that the efficiency of this test are higher than many method of the nonparametric statistics. However, for data in the format of the ordinal scale, its efficiency is dropped. The basic hypotheses the Mann–Whitney U test are [19]:H0: The distribution of data in all groups of the sample are same.H1: The distribution of data in all groups of the sample are different.So, the applied hypotheses of the Mann–Whitney U test for this study are:H0: The data distribution for the CG-JVs group and the SG-JVs group are same.H1: The data distribution for the CG-JVs group and the SG-JVs group are different.There are nine steps for the Mann–Whitney U test as follow [1, 19, 28, 44]:Step 1:Rearrange the data from all groups of sample form the lowest score to the highest score. However, the process have to still keep the track of group’s data. Step 2:Assign the rank to each data. It would be started with the rank “1” for the lowest score and be increased by one for the next score. In the case which there are two or more data being tie, all data will get the average rank between them. The next score also would get the next rank. Step 3:Calculate the total of the ranks for all groups of sample, denoted as “T”.Step 4:Consider the value of T from step 3 and call the maximum T as Tx.Step 5:Consider the group size for each group, denoted as “N”.Step 6:Calculate the U by the Equation (1), as follow:

| (1) |

|

Step 7:From the “the Critical U Values Table” when the level of significance = 0.10 and N1 = N2 = 17The critical U = 96Note because the level of significance, N1 and N2 are the consistency values for the whole study, so the critical U is always as “96”.Step 8:The computed U is more than the critical chi-squareOr 110.5 > 96So, the H0 is accepted.Step 9:It can be conclude that, for the CSQ value of “INT 08: Improper intervention by partners”, there is no difference between the CG-JVs and the SG-JVs at the 90% level of confidence.

Step 7:From the “the Critical U Values Table” when the level of significance = 0.10 and N1 = N2 = 17The critical U = 96Note because the level of significance, N1 and N2 are the consistency values for the whole study, so the critical U is always as “96”.Step 8:The computed U is more than the critical chi-squareOr 110.5 > 96So, the H0 is accepted.Step 9:It can be conclude that, for the CSQ value of “INT 08: Improper intervention by partners”, there is no difference between the CG-JVs and the SG-JVs at the 90% level of confidence. 7. Analysis and Discussion

7.1. Overall Results

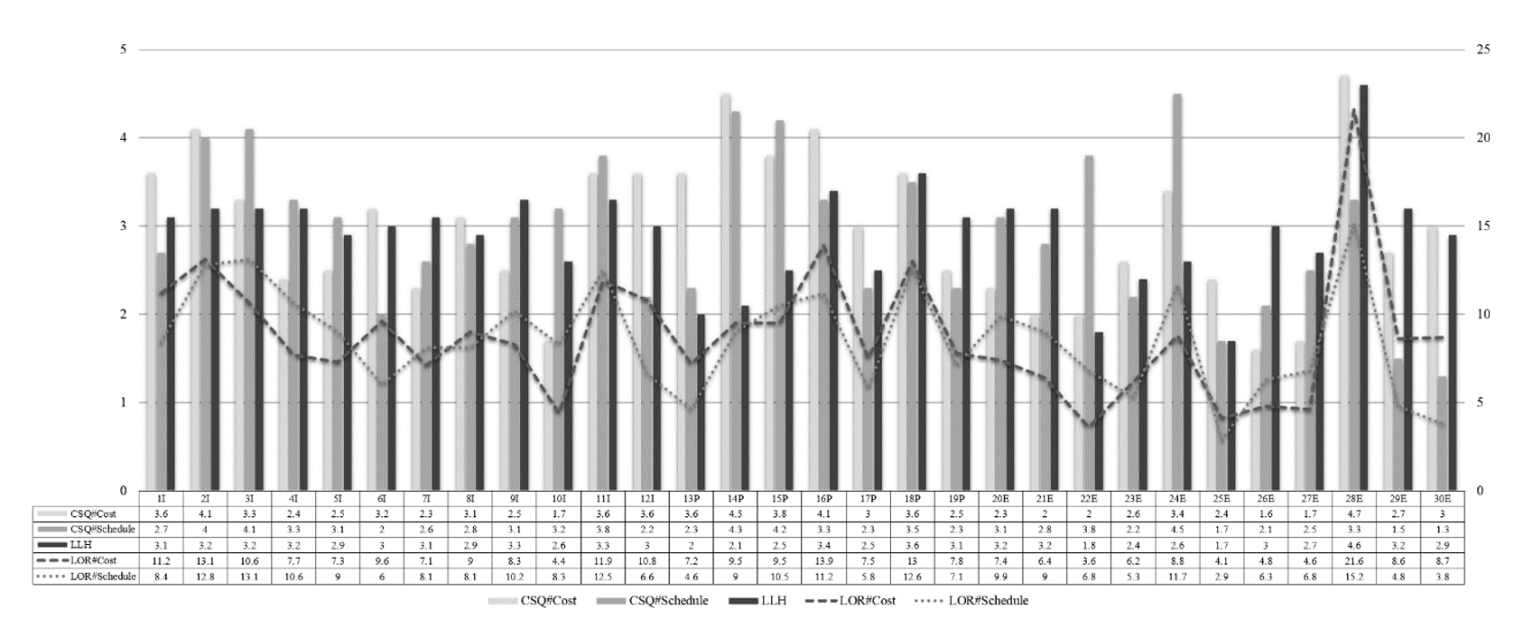

- To compare severity of all ICJV risks in general picture, the level of risk (LOR), being the result from multiplication of CSQ and LLH, is normally used to consider [21, 22]. Figure 2 shows the LOR value for 30 ICJV risks as well as the comparison between LOR of cost and schedule constraint. Comparing with the result in previous studies, it is found that that ranking and LOR of some ICJV risks are quite different. It goes according to the study of Gale and Luo [14] which indicated that the ICJV management in each country is affected by several unique country factors.

| Figure 2. Risk parameters for each ICJV risks on cost and schedule constrain |

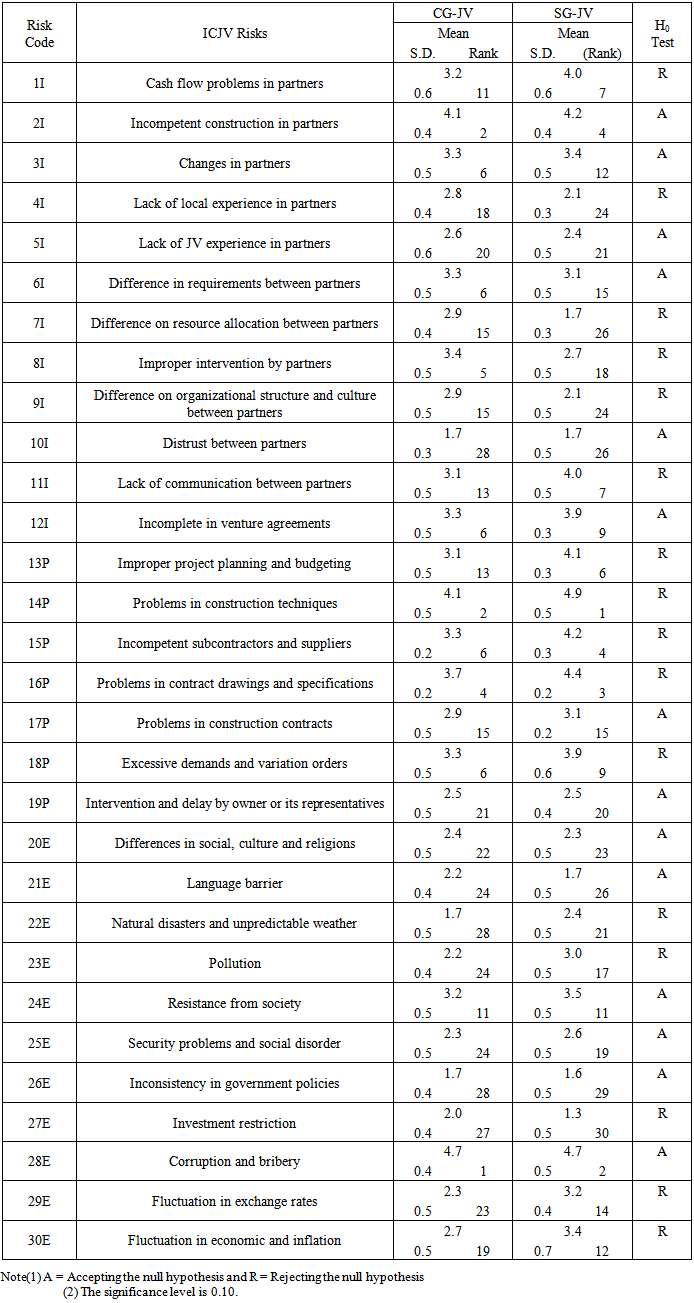

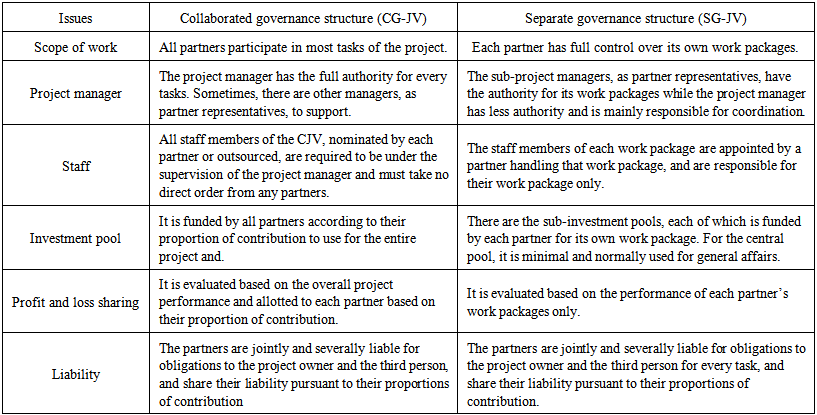

7.2. Impacts on the Cost Constraint

- In general, especially in text books, the triple constraint s are equally important but the cost is always core constraint for contractors for the reality [24]. Failing from its target not only impacts on profit or loss for the current ICJV but also affects the relationship between partners and their business plan. From Table 9, 16 from total of 30 ICJV risks (53.3%) were judged to different between structures at the 95% level of confidence. The difference could be found spreading in every risk categories: internal risk (6 of 12 ICJV risks), project risk (5 of 7 ICJV risks) and external risk (5 of 11 ICJV risks).

|

7.2.1. Internal Risk (I)

- “Cash flow problems in partners” (1I) is an ICJV risk about cash flow of partners during construction period [14]. The CSQ for the CG-JV (CSQ = 3.2) was significant lower than that for the SG-JV (CSQ = 4.0). This certain risk relates with cash flow problem within each partner’s head office [5, 31]. Please do keep in mind that cash flow problem is not a key indicator used to tell that partner is going bankrupt but it is a result from poor income and expense management which does not go according to plan [13, 15]. It leads to cash shortage for ongoing operation. Moreover, there are only a few companies who never encounter cash flow problem [42]. It is likely, for every company, to face with cash flow problem as long as they are still operating. The CG-JV have the collective investment pool which is supported cash partner according the investment ratio and is used for almost tasks in the project. Although it seem risk, it is the flexible and helpful things. Especially during hard time of some partners, they can negotiate with other partners to compromise about supporting cash or dividend [33]. Those actions can be operated without fee from others partners. On the contrary, partners in the SG-JV have to be responsible for their own cash investment pool. If there is bad situation about their cash flow, each partner have to seek support from outside parties. As it also increases the cost of money invested, normally as the interest rate [42].“Lack of communication between partners” (11I) has CSQ for the SG-JV (CSQ = 4.0) was higher than that for the CG-JV (CSQ = 3.1) with significance, partly as the individual structure of the SG-JV is the long-distance cooperation which their communication mostly depends on the formal communication among partners [13, 26]. Because, in the SG-JV, the project manager and personnel of each work package are appointed responsible by a partner, the communication between them is less than normal. If the communication is somehow delayed, the project may be operated with the outdated information and lead to events which task are not compatible [4, 5].

7.2.2. Project Risk (P)

- Based on cost constraint, the project risk category seems to be influenced from the individual structure characteristics. Five out of seven ICJV risks (71.4%) had CQS value for the SG-JV higher than that for the CG-JV. None of CQS value for the CG-JV was higher.“Improper project planning and budgeting” (13P) and “Problems in construction techniques” (14P) are problem occurred when partners lack of efficient experiences [3, 5]. “Improper project planning and budgeting” relates to the situation when the partners plan the operation schedule and/or estimate the cost of management, construction and the overhead cost improperly [24]. The impact from this ICJV risk tends to create unnecessary cost to the partners [13]. As well, “Problems in construction techniques” is about the incapability to continue construction or the incapability to finish construction in acceptable standard due to technical problems [48]. This ICJV risk tends to have the serious and immediate impact toward ICJVs [15]. Their CSQ for the SG-JV were 4.1 and 4.9, respectively which both were significant higher than that of the CG-JV (3.1 and 4.1, respectively). For the CG-JV, it does not matter how partners under estimate, they can still cover the expense from the collective investment pool until over the prepared budgets [30]. On the contrary, for the SG-JV, after responsibility has been delegated among partners, extra payment ratio is difficult for any member to request from others even any of them make mistake in term of estimation [36]. When the project has issue about “Problems in contract drawings and specifications” (16P) (CSQ = 4.4 for the SG-JV and = 3.7 for the CG-JV) or “Excessive demands and variation orders” (18P) (CSQ = 3.9 for the SG-JV and = 3.3 for the CG-JV). The impact for failure in preparing documents, which will be used as references for estimating workload, planning and appraising, will be a great disadvantageous toward the partners [12]. The results from erroneous documents are increasing in work, increasing in materials required or changing to more expensive materials which all of them lead to higher cost for each partner and more time needed for work [47]. “Excessive demands and variation orders” relates to the demand of the owner to change the operational details within the CJV project [48]. The reasons of changes may come from changes in the use of structure, errors or missing details since the beginning or even owner’s personal need [3, 31]. Although it is responsibility of the partners as contractors who must follow changes in work details but they can also ask for more payment and operation time when there are unreasonable or too many changes occur [13]. When it occurs, both sides may have different perspective toward the issue. Most of the times, the owner tries to exploit weaknesses in the contract to avoid being responsible for excessive demands and variation [15]. Both CSQ for the SG-JV was significant higher than that for the CG-JV as if the problem task is responded by only a specific partner, that partner have to carry all of the loss alone.The CSQ of “Incompetent subcontractors and suppliers” (15P) were 3.2 and 4.2 for the CG-JV and the SG-JV respectively. Although partners make usually the guarantee contacts with their subcontractors and suppliers for underperforms [13, 48], they still have to pay the extra cost for these mistakes [4]. The amount of increased cost will base on the kind of problems [42], however for the SG-JV, the partners have to carry these cost by themselves.

7.2.3. External Risk (E)

- The ICJV risk with the most different risk parameter value in the external risk category is the “Fluctuation in exchange rate” (29E). The CSQ for the SG-JV (CSQ = 3.2) was significant higher than that for the CG-JV (CSQ = 2.3). The risk is important to foreign contractors more than that of local and should be considered before venturing [48]. As result of depth interview, the collective investment pool in the CG-JV is the useful tool to decrease the loss by exchange rate. The partners can rest their money or compromise the cash investment until the appropriate time [3, 5].There were a statistically significant difference in CSQ of “Pollution” (23E) and “Natural disasters and unpredictable weather” (22E) between two structures. Their CSQ for the CG-JV were 2.2 and 1.7, respectively, while that for the SG-JV were 3.0 and 2.4, respectively. The results was shown in the same direction that the SG-JV has more impacts with significant. This difference was mainly occurred from that partners in the SG-JV takes separately responsibility for their own operation. When there is an additional cost due to unexpected situations, the partners has to bear those burden alone [5]. The reason why “Pollution” is counted as the risk even though it is caused by project is that when pollution spreads outside of construction site it means contractors cannot control or manage it anymore and it will reflect back to the project itself [8, 31]. Moreover, the impact is directed back to the project itself not specific person [48]. Whether what happen afterwards, it is out of the ICJV’s control. “Natural disasters and unpredictable weather” relates to the natural disasters and the unpredictable weather within the construction site of the ICJVs [4, 34]. For Thailand, most of the natural disasters are related to flood which occur every year. Based on the good principle of construction planning, contractors should have done research about the natural disaster in the area of the project site but in reality, the natural disasters and the unpredictable weather are factors which are difficult to forecast [33]. That is why they are ignored in most of construction project but when they happen, they affect more than it should be [47]. “Investment restriction” (27E) were ranked in the bottom chart for both structures. However, it is only the ICJV risk in the external risk category which CSQ for the CG-JV (CSQ = 2.0) was significant higher than that for the SG-JV (CSQ = 1.3). Although the foreign Investment law in Thailand is clear [29], often, the negotiations about the investment ratio of the CG-JV stretch over the legal limit [8]. The main point of this ICJV risk is laws which limit the proportion of foreign members. For Thailand, normally, the foreigners cannot have the proportion more than 49% of the total investment [29]. Even this is an official laws commonly used, it should not be considered as ICJV risk but there is still uncertainty based on action and preparedness of partners. In some the ICJV project, the partners may ignore this regulation due to lack of experience, haste to establishing or even do it intentionally which omit this part during the negotiation and tend to ignore this limitation [38]. It would later become a problem while doing document work with the government’s offices. It creates unnecessary work and takes time for a new negotiation among the ICJV’s [24, 37].

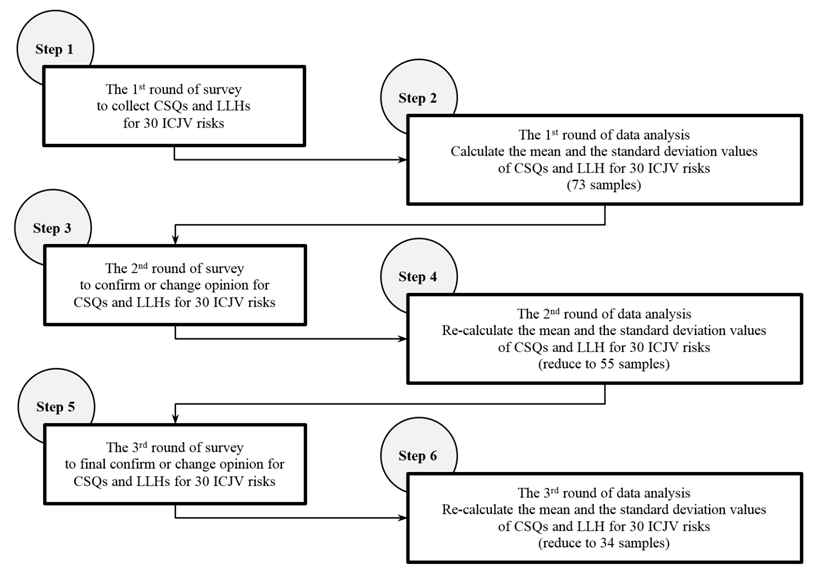

7.3. Impacts on the Schedule Constraint

- As shown in Table 10, the study indicated that 8 out of 30 ICJV risks (26.8%) has their CSQ, under the schedule constraint, differing from each structure, at the 95% level of confidence. Under the schedule constraint, risks may create the events resulting in delayed in construction [4, 15].

|

7.3.1. Internal Risk (I)

- For “Lack of local experience in partners” (11I), in contrast with the cost constraint, the CSQ for the SG-JV (CSQ = 3.7) was significant higher than that for the CG-JV (CSQ = 2.9). This ICJV risk is about how familiar or acknowledgment of construction site’s local environment each partner is [5, 6]. The local environment means the geographical data, the weather data, the labour pool, the materials markets, the product agents, laws, the government officers, relationship with local, and the attitude of local. Normally, this occur with the partners without experience in Thailand.The partners who worked for a few times, the partners who used to work long time ago or the partners who worked in different local environment. In the situation which partners no have experiences in cooperation units but still choose to work independently from each other. The mistake, in management, accounting and law, can be often occurred. The some impact may not increase cost immediately but partners have to fix that by redo the processed again which lead to increase the delay even more. “Incompetent construction in partners” (2I) were ranked in the top chart for both structures. However, the CSQ for the SG-JV (CSQ = 4.4) was significant higher than that for the CG-JV (CSQ = 3.7). The result came from the individual characteristic of jointly style. “Incompetent construction in partners” is very important [6]. Although it can vary among partner but each should be on acceptable level [5]. However, if some partners have too low construction competency, it will lead to many problems in CJVs such as the construction delay and the overrun cost. When any members lose their capabilities to perform any tasks, other partners in the CG-JV would like come in and provide support for what needed immediately to prevent problems in overall project. For the SG-JV, other partners have no responsibility to offer their help due to the separation of their profit and loss. But they have to take an ICJV risk which they may not be able to finish overall project on schedule. After depth interview, although they would like to help the struggle partners but mostly, they will be aware of the problem, lately, as months or years passed. Following that, the past studies showed that many CJVs in Thailand, the partners had to choose the contractor with almost no competency due to the political reasons.For “Lack of JV experience in partners” (5I) and “Difference on organizational structure and culture between partners” (9I) were the ICJV risks which their CSQ for the CG-JV (3.5 and 3.4, respectively) were significantly higher than that for the SG-JV (2.7 and 2.8, respectively). The past experiences of the ICJV projects are the main topic for this risk [15]. If partners have had the past experience in ICJVs either in Thailand or in other counties, they will be familiar with several key processes of the ICJV management. So, the partners should be able to prepare the ICJV documents, to understand the processes of ICJV operation, to gather labour and other resources, to reduce unnecessary risks and problems in the cooperate unit, and to solve the unexpected problems. The main point of “Difference on organizational structure and culture between partners” is differences among partners upon how to direct the task allocation, the coordination and the supervision within their head office’s organization (donated as the organization structure) and differences on staff’s behaviour (donated as the organization culture) [6, 31]. The differences mentioned above are causes of uniqueness for each partner and its staff on how they work. For different organization structure, it will affect how fast or slow decision making is, quality of work, expected cost and organization development. While for different culture, it is reflected through how staff work in term of attitude, communication, worker placement, how they deal with customer, how they deal with boss and how they deal with other parties [5, 18, 41]. The difference was result from the different important of cooperation units [13]. In the CG-JV, most staff members from each partner have to work together in same departments of an ICJV all the time. Moreover, they are required to be under the supervision by a project manager or a head engineer. These collaborations by staff member, whom their organizational structure and culture are different, would increase the potential for problems as mentioned above. So, the CSQ of “Difference on organizational structure and culture between partners” for the CG-JV is 3.4. On the other hand, most partner’s staff members work separately in the SG-JV. The problem from this ICJV risk is less impact because staffs have little chance encounter each other. With the study result, the CSQ of this risk for the SG-JV is 2.8 which was significantly lower than the CSQ of the CG-JV.Again, there were a statistically significant difference in CSQ of “Cash flow problems in partners” (1I) between two structures. Although their CSQ impacting on schedule were not as high as like the cost constraint but the CSQ of the SG-JV (CSQ = 3.2) is significant higher than that for the CG-JV (CSQ =2.3). Each partner may face with cash flow problems at any time [15]. “Lack of communication between partners” (11I) were also still ranked in the top ten chart of schedule constraint for both structures. Moreover, the CSQ for the SG-JV (CSQ = 4.2) was also significant higher than that for the CG-JV (CSQ = 3.4). With the long-distance cooperation, when they lack the communication, as well as the changes or problem are occurred to any task [39], it takes time for other partners to acknowledge the issue and come up with solution, which in the end, affects the delay in schedule [34].

7.3.2. External Risk (E)

- The CSQ of “Differences in social, culture and religions” (20E) were 3.4 and 2.7 while that of “Language barrier” (21E) were 3.4 and 2.3 for the CG-JV and the SG-JV, respectively. Both ICJV risks were a significant difference, implying that the structure, which relay on the cooperation team more then another, is more affected by the problems and conflicts in staff [10, 33].

7.4. Likelihood of Occurrence

- The difference of LLH for ICJV risks between two organization structures were less than CSQ, when comparing with both constraints. As shown in Table 11, there were only five from 30 risks (16.8%) which showed significant differences between the CG-JV and the SG-JV. Three ICJV risks were in the internal risk category while others, relating to cultural differences, were in the external risk category. Again, it was not found in the project risk category.

|

7.4.1. Internal Risk (I)

- Because the more collaboration between partners in the CG-JV is the results of the more collaborative teams, this lead to the CG-JV tend to have more conflict situations about allocation of staff for those team more than the SG-JV. The LLH of “Difference on staff resource between partners” (7I) were 3.5 for the CG-JV which is higher than that for the SG-JV (2.6) with significance.Again and again for “Lack of communication between partners” (11I), the LLH for the SG-JV (LLH = 3.7) was significant higher than that for the CG-JV (LLH = 3.0). The result implied from the long-distance cooperation of the SG-JV. When partners do not cooperate closely, the chances of less communication become even often [4, 6, 18]. However, this LLH can be decreased if both partners have ICVJ experiences, especially together in a previous project [34, 39]. Zhao et. al. [48] found that the experienced partners tend to know effective rhythm of cooperation between partners better than non-experienced ones.The effect of the long-distance cooperation also affect the chance of the “Improper intervention by partners” (8I). For the CG-JV, where partners cooperate closely most of the time, intervention among partners tend to occur much easier and much clearer (LLH = 3.3) than the SG-JV which member tend to work separately (LLH = 2.5). Moreover, if any partner try to reach its own individual objective without acknowledgement by other partners, it can be perceived as the cause to increase the level of intervention on the ICJV [24, 36].

7.4.2. External Risk (E)

- “Differences in social, culture and religions” (20E) and “Language barrier” (21E) were the ICJV risks which their CSQ for the CG-JV (3.6 and 2.9, respectively) were significantly higher than that for the SG-JV (3.6 and 2.8, respectively), partly because the CG-JV are operated by the close-distance cooperation which allows interaction among staff of partners from top to bottom [8, 39]. “Differences in social, culture and religions” is about context for each group of staff within the CJV, who usually represent each partner [5]. The social, culture and religions, are tied with staff personally than organization as they lived within that believed and were taught since young which makes it extremely difficult to change [10, 31]. As, it is related to how they were raised, even people from the same nation still have different contexts [39]. This ICJV risk leads to differences in ideas, attitudes, beliefs and daily lifestyles. It should be concerned as it would surely influence the ICJV operation [47]. When staff work under differences, they tend to be unsatisfied and uncomforted. Moreover, when the feeling get accumulated without a remedy, some of staffs may be unhappy and lead to conflict, resistance or even violence in workplace [18, 34]. At the end, overall staff’s efficacy will drop tremendously to even zero point.“Language barrier” is focused on different communication skill among staff in the ICJV. The impact from this ICJV risk can be varied. First, there is too few communication occurs as staff try to avoid communication among each other as they are afraid that they may not communicate well [39]. Next, the communication may take long time [4, 6]. Last but not least, when staff understand things differently from the same document, it affects the ICJV in term of legal and financial, technical support. which may lead to the ICJV’s failure or partners breaking up [31, 48].After in-depth interview, it was found that, nowadays, both ICJV risks tends to be more complex as staff of an ICJV may not even be someone who comes from only countries of partners. They may be hired from other countries to assist the project. So, the social, culture, religions and language skills are more different, harder to manage and often to occur [37, 48].

8. ICJV Risk Treatment

- The risk treatment is the options for responding the critical risks to mitigate, avoid, share or transfer their impacts and/or the probability to occur [21]. Because the most of previous studied were focused on the risk assessment during the construction phase, there are many risk response options which have already recommend for the risks in this phase [37].The mitigating options for “Lack of communication between partners” (11I) are the official and unofficial systems of communication between partners within an ICJV. To effectively reduce the CSQ and LLH of the ICJV risk, the systems have to be set up before the construction tasks in the ICJV would start [6, 13]. Moreover, there are three parameters supporting the success of this risk treatment option [5, 26, 34, 39]. They are:1) Awareness of the importance of communication between partners by staff of each partner2) Serious attentions in the monitoring and control by the supervision and 3) Trust and the peace of mind of the staff who communicate. These parameters would be sustainable in the ICJV when the executives or managers of all partners pay the attention to the parameters at the beginning [3, 48]. For the CG-JV, the framework of the communication systems has appeared already in the ICJV organization. The manager of the ICJV just does it to be clearer for every staff [13]. In contrast, the manager of the SG-JV has more work to do. First, the manager must inform the partners to realize that it still needs to be communication between partners, although the tasks of the ICJV are done separately [37].For “Lack of JV experience in partners” (5I) and “Lack of local experience in partners” (4I), the first step for the risk treatment is that the partners should not try to pretend or ignore that they understand the practices or conditions for the local law, the project site and the supply chain of construction resource [6, 34]. If the partners do like this, the two risks would not bring up at the first [35, 36]. Then, the risks would be retained and their impacts would gradually accumulate until the worse risk events appears clearly in front of the partners [15, 46]. On the other hand, if the situations were shown at the beginning, the options for responding these two risk can be done through the help of the experience partners [4]. In case that all partners lacking of experience, the ICJV should seek the advice and/or assistance from the external agencies such as the independent consultants [37].

9. Conclusions

- The main objective for this study is to investigate whether the different organization structures of ICJV is a risk which makes risk parameters, CSQ and LLH, different from each other. After analysing 34 set of questionnaire from respondents collected via the process of Delphi technique, it can be concluded that there are the statistically significant difference in CSQ on cost and schedule constraint or LLH for ICJV risks between the CG-JV and the SG-JV. These differences are results of unique characteristic among two organization structures including: 1. As a result of working together closely of staffs between partners in the CG-JV, CSQs of “Difference on organizational structure and culture between partners” (9I), “Improper intervention by partners” (8I), “Lack of communication between partners” (11I), “Language barrier” (21E) are significantly higher than the SG-JV as well as LLHs of “Improper intervention by partners” (8I), “Differences in social, culture and religions” (20E) and “Language barrier” (21E) are significantly higher than the SG-JV. On the other hand, working separately of staffs between partners in the SG-JV lead to that LLH of “Lack of communication between partners” (11I) is significantly higher than the CG-JV.2. While partners in the CG-JV would share fund, labour, staff, equipment and other resources according to their proportion of contribution to use for the entire project, sharing resources in the SG-JV are very limited. As the results, CSQs of “Cash flow problems in partners” (1I), “Improper project planning and budgeting” (13P), “Problems in construction techniques” (14P), “Incompetent subcontractors and suppliers” (15P) and “Problems in contract drawings and specifications” (16P) for the SG-JV are significantly higher than the CG-JV.3. The cooperation of partners in the CG-JV for managing an ICJV is over than the SG-JV. This action lead to that the CSQs of schedule for “Incompetent construction in partners “(2I) and “Lack of local experience in partners” (4I) in the SG-JV are significantly higher than the CG-JV. However, as a result of cooperating together too closely, the CSQs and LLHs of “Difference on resource allocation between partners” (7I) and “Improper intervention by partners” (8I) in the CG-JV are significantly higher than the SG-JV.It can be conclude that partners in SG-JV have loose cooperation. So, the most of joint process between partners occur among executive level. For the CG-JV, staff of each partner, who have differences in many aspects, come to work together from top level to bottom level. So, it is not surprised that most of CSQ and LLH in the internal risk category, for the CG-JV, have higher values than the SG-JV. However, lack of communication between partners is an excepted ICJV risk in this category which affects SG-JV more than the CG-JV due to its nature, that staff between partners cooperate loosely, which considerably increase LLH and CSQ of ineffective communication goes worse as time passes. On the other hand, the values of CSQ and LLH for some ICJV risks in the SG-JV are higher than the CG-JV when they are in the project risk category. The CSQ of these ICJV risks directly impact to increase cost for operating the project. As partners in the SG-JV cannot request for more income from the ICJV to support those unwanted cost while for the CG-JV, all income from project’s owner will be put in collective pool and distributed to all member after paying all expenses. This study is not aimed to indicate that which of the ICJV organization structures is better than other but aim to discover the different characteristic of risk parameters on the different structures. Moreover, with different time and situation, the suitable ICJV organization structure for each partner can be changeable all the time. So, understanding in these differences can lead the management team to prepare the more effective solutions to decrease impact of ICJV risk and increase the performance of the ICVJ.Direction of the future study to improve the result of this study can be divided into two topics. The first one is increasing number of sample or trying to use other tools to decrease the bias of respondents. So, the parametric static method can be adopted to get more the more reliable statistic test. Next samples should be grouped based on experience and size of partner’s firm in order to analyse whether there are any other ICJV risks, apart from organization structure, which makes different in value for CSQ or LLH. However, this action increases the need on the number of sample.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors gratefully acknowledge the Graduate School of Chulalongkorn University for supporting this research.The authors would like to thank officers and engineers from the Thai construction and civil engineering companies for supporting survey processes in this study which are applied to test the hypothesizes and understand the risk management for an ICJV.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML