-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2015; 4(4): 122-127

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20150404.03

A Comparative Analysis of Standard Labour Outputs of Selected Building Operations in Nigeria

Chukwuemeka Ngwu1, Peter Uchenna Okoye2

1Department of Quantity Surveying, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria

2Department of Building, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Peter Uchenna Okoye, Department of Building, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The study compared the labour outputs of building operatives in sixteen work items of concrete work and blockwork across the South East of Nigeria. A total of six organised building sites were selected using purposeful sampling technique. Assumed labour outputs were obtained through a questionnaire survey administered to the operatives and determined labour outputs were obtained through a detailed work study. Student t-test and Pearson correlation coefficient (r) were implied to assess the statistical significant difference between the claimed and determined labour outputs of the operatives. The results showed that the determined labour outputs were consistently lower than the claimed outputs with varying degrees (i.e. between 5% and 50%). The results further revealed from t-values, r and p-values that the determined labour outputs were statistically different from the claimed labour outputs from the operatives at 5% significant difference and degree of freedom of 10 in all the work items considered. This pointed to the fact that cost estimates and programmes based on guess figures could be misleading and unreliable. The study has provided basis for estimating and planning using the determined labour outputs for the work items studied, and also served as a stepping stone for further escapade in other aspects of building works and building types. It therefore urged the practitioners to desist from making use of guess figures of labour output in determining the cost estimates of or designing the construction programme for building projects. It then recommended further studies where labour outputs of other building operations and building types, other than the ones considered in this study could be determined using the same process.

Keywords: Building Operations, Construction Programme, Cost Estimation, Labour Outputs, Work Study

Cite this paper: Chukwuemeka Ngwu, Peter Uchenna Okoye, A Comparative Analysis of Standard Labour Outputs of Selected Building Operations in Nigeria, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 4 No. 4, 2015, pp. 122-127. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20150404.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- There is a dearth of reliable information on output levels of building operations in Nigeria [1]. This is so because there are no established output figures for different construction operations which could be used for estimating in the country. Firms base their outputs for estimating and planning purposes on experience which at best are educated guesses [2].Most times estimates are based on information obtained from site operatives, using similar priced Bill of Quantities of previous projects and updating the bill items by percentages or by mere physical adjustment. According to Wood [3] we should beware of readily accepting any information from an operative without being completely satisfied that he understands precisely what is meant by your question.Although most Quantity Surveying firms maintain cost libraries [4], such as the monthly Builders and the Quantity Surveyors’ magazine which usually contain information on construction matters and current prices of labour and materials in the various states of the Federation; there is even construction price book [5] which also contains prices of labour and materials in Nigeria. None of these contains data on outputs of construction operatives except Consol’s Nigerian building price book [6] which has very scanty information on Nigerian construction workers average output and local daily charges. Attempt by Alumbugu et al. [7] yielded little improvement but could not be generalised. Standardisation in construction is primarily aimed at establishing standards in the use of labour, materials and machines. These three elements in standardisation are sometimes referred to as technological standards or constants [8]. Standards in the use of labour are standard time (St) and standard output (Sop). Standard time is the quantum of time which it takes a workman or group of workmen to produce a good quality product under an ideally organised labour force and working condition. Its unit of measure is hrs/m, hrs/m2, hrs/m3. Standard output is the quantum of good quality work accomplished by a workman or group of workmen in one working shift or working hour or day under ideally organised labour and working condition. The unit is usually m2/hr or m2/day, m3/hr or m3/day [8].According to Udegbe [9], there is no known standard theoretical yardstick for determining the financial value of painters daily output. This he said leaves clients with the choice of paying any sum of money for services rendered. While it is recognised that there are no established standards for different construction operations in the country, there is no sufficient justification to leave production outputs in the realm of guesses [10].Sometimes estimators depend on constants obtained from operatives on one site for estimating purposes. Needless to say that rash, off-the-cuff, wild guess can subsequently inflict a heavy financial punishment. To buttress this point Olomolaiye and Ogunlana, [1] aver that the outputs of joiners, bricklayers and steel fixers in seven public institution building projects in Oyo State of Nigeria, determined on the sites were lower than the claimed outputs of the operatives. The differences between claimed and determined outputs in each task vary between 3% and 42% [1]. However, this was not statistically verified in that it was based on the aggregate mean difference between the claimed and observed outputs of the operatives.Therefore, based on the earlier work of Okoye, Ngwu and Ezeokoli [10], this study is aimed at comparing the labour outputs developed through detailed work study (determined standard output) and claimed labour outputs of operatives on different building work operations in six selected building projects in the South-East Nigeria. It also determines statistically if significant difference exist between the claimed labour output of the operatives and determined labour output in the selected building operations in the projects also selected for the study.

2. Methodology

- Six building sites were first surveyed in the South East States of Nigeria to determine quantifiable construction activities, sites located in a planned environment, organised sites with almost the same working practices, sites with reputable indigenous contractors, and sites in stages of construction suitable to the processes under investigation. These would facilitate the comparative study and analysis for acceptable results.Concrete work and blockwork in superstructure were the building processes studied. They were broken down into operations to facilitate subsequent synthesis. Concrete work involved operations like batching of materials into a mixer, transportation, placing and compaction. Blockwork operations include batching of materials into a mixer, transportation of mortar, placing of mortar and setting of blocks in place. Each operation involves certain number of tradesmen and labourers to carry them out.Furthermore, activity sampling was carried out, particularly field counts. The processes where field count was carried out in this study included concreting, carpentry, cutting, bending and fixing of reinforcement, and block laying; each with a given number of operatives made up of skilled manpower and labourers which form the gang. Field counts, that is a quick count at random intervals of the number of operatives working and not working at a given time were observed and recorded. An indication of the performance such as:

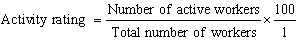

| (1) |

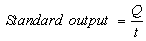

| (2) |

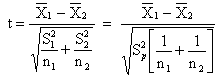

| (3) |

are sample means for claimed and determined labour outputs respectively; S21 and S22 are sample variances; n1 and n2 are sample sizes, and

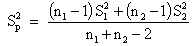

are sample means for claimed and determined labour outputs respectively; S21 and S22 are sample variances; n1 and n2 are sample sizes, and  | (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

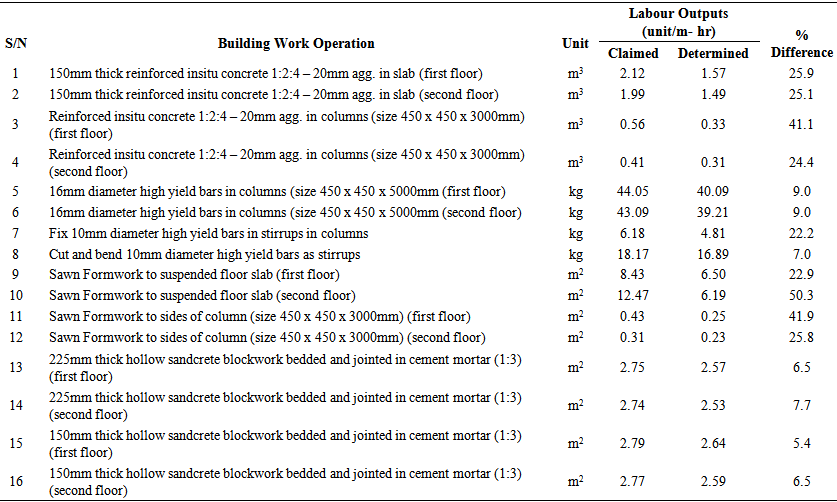

| Table 1. Results of computed average claimed and determined labour outputs for different building work operations |

3. Results and Discussions

- Table 1 depicted the computed average claimed and determined labour outputs of the building operatives on different work operations in six selected building projects across the study area. The claimed labour outputs were computed from the results of the questionnaire administered to the site operatives regarding their output level on different work sections. These figures were taken to be assumed or guess from their experiences over the years. However, the determined labour outputs were the results of the detailed work study of the labour output of the same operatives on the same building projects and work operations for a determined period of time in a day (usually eight-hour work).It was observed that there is marked difference between the claimed labour output and determined labour output in all the building operations under investigation. Further analysis revealed that the difference between the claimed labour output and determined labour output of the operatives ranges between 5% and 50% in each work item.However, the percentages represented the minimum and maximum percentage differences between the claimed labour output and the one determined through a detailed work study.

3.1. Test of Hypothesis

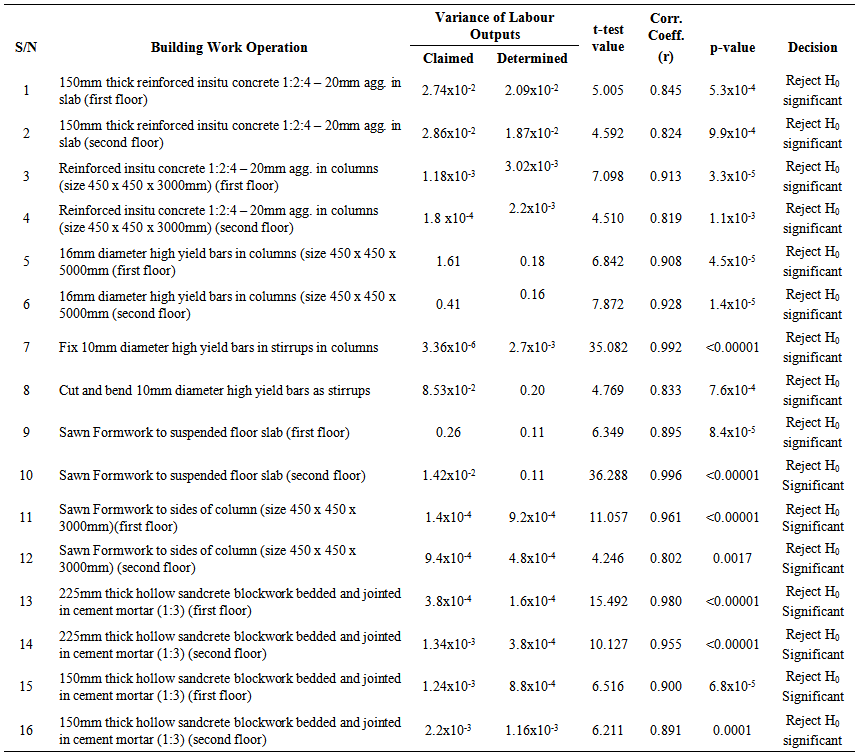

- To determine the significant difference between the claimed labour output and determined labour output, the following hypotheses are postulatedH0: There is no significant difference between the claimed labour output and determined labour output of the building operatives on site.H1: There is significant difference between the claimed labour output and determined labour output of the building operatives on site.The results of this analysis are presented in table 2.

| Table 2. Results of the t-test and correlation coefficient of the average claimed and determined labour outputs for different building work operations |

4. Conclusions

- The dearth of reliable information on output level of building operatives in Nigeria has continued to resonate concerns among the practitioners and other concerned stakeholders in the building industry. The act of using guess data based on experiences or information from the site operatives for cost planning, construction programming and cost estimates have proved to be unreliable, unrealistic and misleading. Thus, the purpose of work study which is to provide factual data to assist management in making decisions and to enable them to utilise with the maximum efficiency all available resources (that is labour, plant, materials, and management) by applying systematic approach to problems instead of using intuitive guess work has provided a reliable alternative.To this end, this study has presented the results of the assumed labour output of the operatives of building works and determined labour output through a detailed work study on the same building works and projects. It went further to comparing the two outputs, and determined statistically the difference in the two labour outputs. This study has demonstrated significant difference between the assumed labour output and the determined labour output in building operations studied. The study has further highlighted the dangers of using guess figures in estimating building works and also underpins the importance of a detailed work study in realisation of acceptable labour constants for building works. It has therefore, provided basis for estimating and planning, using determined labour outputs for the work items studied. It has also given inkling for further escapade in other aspects of building works and building types.Indubitably, the study has broaden the scope of knowledge in this field of study in the sense, that researchers can now work on the results of the study to further their course of study. Practitioners would also rely on the results of this work to produce a reliable cost estimates and construction programmes for building projects. Finally, the results of this study would minimised the challenges of accurate cost estimate, construction programme, project planning and control, and pricing of bills of quantities through realistic determination of optimal labour output in the execution of building projects. Based on the enormous potentials of this study, it is recommended that practitioners should desist from making use of guess figures of labour output in determining the cost estimates or designing the construction programme for building projects. Further studies are also recommended, where labour outputs of other building operations and building types other than the ones considered in this study could be determined using the same process.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML