-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2015; 4(3): 73-79

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20150403.02

Towards the Development of Tender Price Index for Effective Cost Planning in the Ghanaian Construction Industry

Kissi E., Adjei-Kumi T., Badu E.

Department of Building Technology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi

Correspondence to: Kissi E., Department of Building Technology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Cost planning remains an effective medium for administration of construction projects that devoid projects from being under-grouped either cost or time overruns. The construction industry all over the world, thus in both developed and developing countries are characterised with an issue of lack of effective cost planning practices before, during and after construction projects. It is imperative that construction professionals tackle the issue of cost planning with a professional edge using various effective techniques. However, in developing countries, effective cost planning remains pathetic and a major concern to construction stakeholders. For instance, in Ghana nothing can be construed in terms of measures used for effective cost planning. Hence, the abandonment of construction projects resulting from poor construction cost planning and control is a well-known phenomenon in the Ghanaian Construction Industry (GCI) with mass housing projects appearing to have been abandoned as progress of work has stalled over the years. In an attempt to address this problem of construction cost planning in the GCI, the aim of this paper is to examine the relevance for developing tender price index for effective cost planning in the GCI. Cast in the qualitative approach, and adopting content analysis stances, the study established that the relevance of developing tender price index for effective cost planning inevitably cannot be doubted. About 90% of the respondents agreed to this fact. Thus, the foregone research will contribute immensely to the improvement of GCI.

Keywords: Development, Tender Price Index, Cost Planning (CP), Ghanaian Construction Industry (GCI), Ghana

Cite this paper: Kissi E., Adjei-Kumi T., Badu E., Towards the Development of Tender Price Index for Effective Cost Planning in the Ghanaian Construction Industry, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 4 No. 3, 2015, pp. 73-79. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20150403.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The reliability of tender price forecast of construction projects have been a subject of debate among researchers and practitioners in the built environment as it could distress the decision of clients, contractor’s, financial institutions and others [4]; [40]; [44]; [36]. However, the consistent increment in prices of goods and services in the construction industry as a result of escalation of prices which are perceived in all sectors within the industry has brought this debate into a sharper focus. Pressure on prices of resources in the industry continues to rise, and indeed evidence shows that there exist an upward increase in services and products offered by the construction industry in recent times [15]; [10]. Globally, the trend of prices of construction products continues to increase which has been subjected to shocking phenomenon during the period of economic austerity in both developing and developed countries [17]. Given, the complexities and tentativeness of price mixes in the industry, clients find it difficult in choosing contractors or suppliers for projects or services delivery [42].Agreeing on the measure of price, a client’s willingness and commitment to undertake a project remains an intriguing event with more dynamic and evolving strategy. Thus, the prices use for estimating and arriving at a particular tender price remains a primary objective for every client. Accordingly, [4] argued that it remains vital information upon which a client will decide whether to engage in the construction project or not. Underlying this objective is the attainment of value for money. Clients who are therefore willing to construct will definitely ask a question of how much the project will cost. Answering this question, [8] indicated that if price estimates are too high, clients are discouraged from continuing the scheme or project, and also if the estimates are too low the resultant effect is an unnecessary delay or abortive design in the initial stages since the amount committed do not meet the actual cost of the project. However, recent indications in the construction industry show that there is inclination towards traditional procurement system, especially in developing countries with government as the main underwriter, in which contracts are awarded to the lowest bidder [34], [26]. As results, bidders force their tender prices down by reducing their profit margin or eroding their profits [26]. This low price bidding strategy has negative or adverse consequences on construction projects. Notable among these consequences are extensive delays resulting in abandonment of projects, construction disputes and negative cash flows [2], [8]. For clients, the preparedness to undertake projects among other things depends on the ability to invest money. Therefore, the financial soundness of projects is imperative. In juxtaposing, clients need to be informed in advance of their likely future financial commitments and cost implications, accordingly the required approximation of building cost which is based on historical cost data updated by the forecast Tender Price Index (TPI) as design evolves [29]. Thus, consistent prediction of tender price index is critical to stakeholders in terms of decision making. Similarly, [12] argued that reliability of the estimates depends significantly on the accurate projections of the TPI. TPI is an output index describing the average building prices within a specific timeframe.In Ghana, studies revealed that there is a continuous movement in prices of construction outputs [33], [6] hence, greater influence on tender prices. This trend is expected to continue because factors responsible for the increased prices trend remain constant [1]. Concisely, effective cost planning practices remains an ultimate option in achieving a desirable result, thus a catalyst for achieving a successful project within a predetermined tender price without cost overruns or its anticipated adversaries. [8] opined that effective cost planning add real value to a project by enabling informed decision-making from the inception to completion of the project. TPI therefore, remains an effective medium to achieving acceptable cost planning process.

2. The Need for Tender Price Index

- The accurate and reliable determination of tender price for projects remains a critical problem which has saddled the construction industry [3], [40], [44] this problem is more acute in developing countries [11]. Likewise, one persistent problem in Ghana is that, the quality and reliability of estimates provided by Quantity Surveyors sometimes are doubtful [25]. Thus, most projects in developing countries, including projects in Ghana, end up grossly over-budgeted and over-time.Furthermore, [25] reiterated that, the inability of Quantity Surveyors to provide quality and reliable estimates at all times is as a results of lack of effective cost planning in the industry. However, this problem can also be attributed to the lack of tender price index in the Ghana construction industry. Similarly, [38] as cited by [19] argued that in most developing countries such as Ghana, there are no organisations that have endeavoured to compiled and published construction data and the unavailability of such information has hindered effective planning and pricing of projects. Consequently, if a construction firm fails in wining contracts, then resources invested are wasted. On the other hand, if clients lack the knowledge on how much they are expected to invest in a project, they become reluctant to invest. More importantly, if consultants also fail to give realistic price for tender, they lose credibility. Therefore, it is important for construction stakeholders to offer suitable tender prices for intended projects based on previous tenders.However, in developed countries, such as United Kingdom, Hong Kong and United States of America, there are established institutions who engage in the development of tender price index: for instance, the Building Cost Information Service of United Kingdom, Architectural Service Department of Hong Kong and Engineering News Records of United States of America are examples of such institutions. Notwithstanding, construction professionals in developing countries are not able to adopt these indices because of the extent of influence that cultural difference have on various decisions making. These cultural differences are related to the values, attitudes and norms which will not work in developing countries such as Ghana [28]. Similarly, [39] opined that it is even more difficult to adopt or maintain a scientific strategy to measure decisions that work in one country to another due to the diversity and complexity of construction organizations that exist in different countries. These cultural indicators are mainly due to variations in market conditions that exist in different geographic contexts [35]. Drawing from this, these cultural differences in terms of tender price are classified as micro and major in terms of their impact on the development of tender price index. For instance the micro indicator differ from one country to the another thus the type of building, standard form of measurement, level of professional competence and pricing strategies while the macro indicators includes: gross domestic product, inflation, exchange rate, interest rate, prime building cost index and consumer price index. These micro and macro indicator are interrelated, having linked with one another. Similarly, there are changers which have greater impact on both the micro and macro indicators, thus depending on the level of growth of economy within particular country understudy, these are political, corruption, procurement and unemployment. As aforementioned, tender price is imperative in the successful delivery of projects and TPI is more important in decision making right from the inception stage. However, the establishment of tender price is highly fluctuating in the construction industry and there has been a wide disparity between annual rates of tender price and building costs [3]. Tender Price Index (TPI) therefore, is used to track the historical trends in the movement of tender price levels of construction contracts let out during the respective periods. In addition, to reflecting the changes in material and labour costs, TPI also takes into account the elements of competition in the market, the risks and the profit factored in the Contractors’ bids [24]. Besides being used to establish historical cost trends, TPI also serve as a useful tool for providing an indication of future cost trends. Accordingly, future research seeks to develop tender price index as means for forecast tender price. This findings will help most clients to know how much to spend on a project. Hence, the need to develop a model for predicting tender prices index in the Ghanaian Construction Industry. This will help to achieve efficiency in the cost planning of construction projects in Ghana.

2.1. Ghanaian Construction Industry

- The Ghanaian Construction Industry presents a viable medium for reviewing cost planning practices. As cost planning remains an inevitable phenomena in the construction processes, which presents a remedy for achieving stakeholders’ expectations in terms of building within budget. The industry remains one of the growing indicators to the national economy for instance according to [46] as cited by [7], an approximate annual value of public procurement for goods, works and consultant services amount to US$600 million, representing about 10% of the country’s GDP. Accordingly, it employs more people [41] in the economy; cost planning remains the backbone in achieving ultimate within available constraints. Similarly, the volatile nature and the complexities of design have increased due to technological advancement, so as the need for CP becomes more important in the construction industry [22]. Subsequently, as the purse of public or private funds are the available medium for which infrastructure are raised either for offices, school, factories among others, the need for scrutiny of expenditure become more intense, as contributors expect value for money. CP remains the ultimate shoulder for effective spending. Concisely, a successful project means that the project has accomplished its technical performance, maintained its schedule and remained within budgeted cost [14].Notwithstanding, the growing aspiration for betterment of the Ghanaian Construction Industry with its wider implication on the national economy, it is reported that more than ninety percent (90%) of construction contracts are procured by the traditional design-bid-build method [31]where the project outperformed badly. More so, contemporary project management adopted by some construction professionals is characterized by late delivery, exceeded budgets, reduced functionality and questionable quality where sixty percent (60%) of clients said that cost targets are not met [43]; [9]. [13] revealed that 75% of water drilling projects in Ghana completed between 1970 and 1999 exceeded the original project schedule and cost whereas 25% were completed within the budget and on time. [30], also reported that a survey by non-banking financial institution indicated that cost overruns ranges between 60 to 180%. In buttressing this, it is reported that a preliminary investigation into Ghana Education Trust Fund (GET Fund) Projects for Senior High Schools in the Ashanti Region revealed that out of ten (10) projects which were completed between 2006 and 2008, only two (2) were completed within budget while the remaining eight (8) were completed over the cost budget with the cost overruns ranging between 1% to 65% (Architectural and Engineering Services Limited (AESL); Progress Report on GET Fund Projects –3rd Quarter, 2009). Similarly, [25] observed that consultants’ cost estimates in Ghana overrun on the average by 40%. It is also worth noting that projects in Ghana are mostly abandoned due to the fact that construction projects experience time overruns more than forty-eight months in Ghana [5], [30] as a result the cost of the project from the initial estimate escalate. In furtherance to this, [21] reported that more than US$1,000 billion is paid annually in bribes, and the volume of bribes exchanging hands for public sector procurement alone is roughly 200 billion dollars per year due to the fact that proper cost analysis are not done. Bribery kickbacks often represent a sizeable proportion of the total contract value; estimates by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) group on corruption suggest that bribes can represent 10-25% of total contract value, which may be considerable in defence or infrastructure projects [21]. Lastly, it is reported by the [45]; [46], that the industry experiences delay in payment to service providers (contractors and practitioners), also affects payments of salaries and wages of their staff [14]. The big question that draw closer to readers might be that are there adequate cost planning activities before project start or are there effective techniques for ensuring value for money?Drawing from the above, it can be advanced that the Ghanaian Construction Industry behaves like a dancing wind without a tail to hang on, leaving stakeholders to speculate the medium in which their initial investment could afford. Stakeholders at the design stage will like to know how much they can invest, especially client’s budget for project must be certain or must be pegged at a certain amount, but there remains an inconclusive decision on the measures, procedures, formula among others in determining the total investment portfolio. Clients’ decision to embark on a proposed construction project relies on building professionals advice. Hence, clients do ask for the designs and subsequently the probable cost, which indicates how much the project will cost. The enormousness of the cost depends on several factors such as nature, size and location of the project as well as the management organization, among many considerations. However, one of the most significance factors that a promoter is much often interested in is achieving the lowest possible cost that is consistent with its investment objectives [37]. It is therefore essential for professionals to recognize that historical data is the mainstay in answering these questions, thus prediction of tender of price of the building. Since historical cost data are often used in making cost estimates, but it is important to note that price level changes over time. Hence, trends in price changes can also serve as a basis for forecasting future costs. Accordingly, the forgone research is motivated by examining the level of knowledge and understanding of stakeholders on tender price index for synchronization of regulated tender prices in the Ghanaian construction industry. However, it must also be noted that there are several studies on this in developed countries (see for instance [3], [37]; [29]; [27] among others). Conversely, developing countries [16], explored the application of factor cost indices in Kenya and [19] also developed a factor cost index for Egyptian construction industry. In the Ghanaian Construction Industry, [6], [1], developed construction cost indices which are used in checking fluctuation, however the issue of TPI has not been explored making it more appropriate for this study to be conducted.

3. Research Methodology and Design

- This research present a preliminary survey leading towards the development of tender price index in the Ghanaian Construction Industry for effective cost planning practices. Hence, data collection was done with both primary and secondary data consideration. In the perspective of the secondary data, a critical literature review was conducted and in collecting primary data, open ended questionnaire was used. This questionnaire was administered to consulting quantity surveyors using purposive and snowballing sampling technique. These two techniques were adopted due to the fact that firstly, the research was interested in a sample that will give best perspective on the phenomenon of understudying and secondly, in attaining the sample size because of the difficulties encountered in assessing the population. In all, a total of fifty-two (52) retrieved. Quantity surveyors were targeted as the main respondents due to the fact that they are custodians of pricing and cost in the construction industry and the researcher deem edit appropriate that they are capable of providing relevant answers needed for this research. Field data gathered through the questionnaire survey were subjected to descriptive analysis using frequency, percentage and bar charts in order to present the pictorial overview of stakeholder understanding.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Respondent Background Information

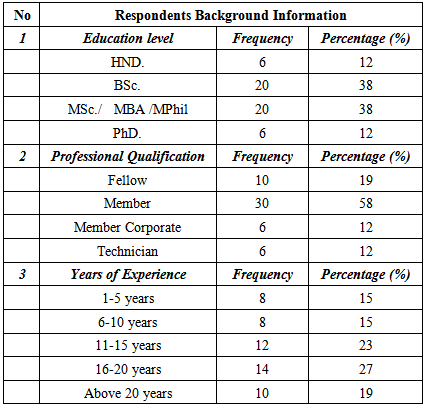

- Data regarding the demographic characteristics of respondents were analyzed using descriptive analysis. The goal was to present both the background information of professionals who took part in the study. Knowing the background information will help generate confidence in the reliability and credibility of data collected. The demographic information included educational level, professional qualification and years of experience (See Table 1).

|

4.2. Knowledge on Tender Price Index

- This section presents the result of the fieldwork which dealt with the level of knowledge of consulting quantity surveyors on tender price index. These consulting quantity surveyors were purposively selected as a result of their experiences and profile of works they have undertaken. Thus, it represents a true empirical data on quantity surveyors in-depth understanding and knowledge on tender price index. However, there was a great misunderstanding on what really constitute TPI in terms of it usage among the consulting quantity surveyors. For instance, some refer to this as “It indicates changes in labour, material and plant, “it is used for estimating unit cost of a project”, “this far indicate that the quantity surveyors do not understand the term”.This clearly showed that knowledge on TPI is very low among consulting quantity surveyors thus the need for its development.

4.2.1. Monitoring of Tender Price Movement

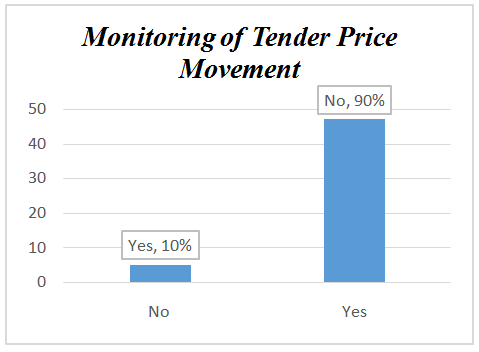

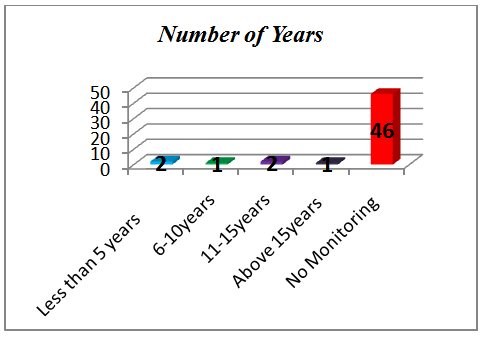

- In referring to Figure 2 below, only5 of the consulting firms representing 10% indicated that they monitor tender price movement. 90% represent “no” shows that majority of consulting firms in Ghana do not monitor prices movement in tender prices.

| Figure 2. Monitoring Tender Price Movement |

| Figure 3. Number of years of Monitoring |

4.2.2. Barriers to Tender Price Development

- From the survey, respondents indicated that the following are some of the specified barriers to the development of Tender price index in the Ghanaian Construction Industry: • Lack of data for cost analysis;• Contractors do not price well;• Inflationary trends/unpredictable economic condition; • Lack of knowledge/experience of importance of TPI;• Lack of specialists’ interest in cost information and data; • Non-cooperativeness of professionals to give out information; • Inappropriate funding/ lack of financial incentive in the development of price indices; • Estimating problems;• Arithmetic errors in tender; • Institutional barriers;• Regional and sectorial challenges;• Untimely update and delivery of index; and • Non-standardization of construction methods.

5. Conclusions

- The development of tender price index as abovementioned in the above discussion raised a lot of cost planning development issues in the construction industry. The need to sojourn the already known phenomena of cost overruns juxtaposing with unrealistic tendering figures compounded with the syndrome of under and over pricing in most developing countries, which Ghana is not an exception leaves much to be desired. Thus, is it imperative that stakeholder takes a key interest in the development of such an important tool. From the survey, it could be clearly opined that most consulting quantity surveying firms are inadequately equip with knowledge on tender price index. For instance, level of understanding on TPI was very low, thus only 10percent indicated they have been monitoring movement of price. Arguably, they could not give any specific techniques adopted. Agreeing that, monitoring of tender prices can done by comparing previous projects with current projects, it can therefore be interpreted that effective cost analysis cannot be made. Thus, quantity surveyors in the construction industry have relinquished its authority in providing the best approach in forecasting tender price movement. This suggests that is there an ineffective cost planning techniques to tender pricing in most developing countries; the need for tender price index becomes more urgent. Furthermore, the implication is that tender price index development remains a critical issue in the construction industry, hence the need for this research. This study presents a call for stakeholders including academia, practitioners and governments to join forces in developing such effective tool for the advancement of construction industry as a whole.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML