-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2014; 3(2): 57-64

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20140302.03

Criteria and Measurable Indicators for Assessing the Performance of Public Works Contract Award Process in Chad

Sazoulang Douh1, Theophulus Adjei-Kumi2, Emmanuel Adinyira3, Bernard Baiden2

1PhD student, Building Technology Department, KNUST, Kumasi, Ghana

2Senior Lecturer at Building Technology Department, KNUST, Kumasi, Ghana

3Lecturer at Building Technology Department, KNUST, Kumasi, Ghana

Correspondence to: Sazoulang Douh, PhD student, Building Technology Department, KNUST, Kumasi, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

A major problem in performance assessment is the selection of appropriate indicators or measures. The objective of the study is to establish relevant criteria and related quantifiable indicators to assess performance of works contracts award process. Through a quantitative method with an adapted AHP methodology, the weights of identified criteria and related indicators were computed. The results show that relevant criteria in order of importance are Transparency, Fairness, Competitiveness and Compliance for having attracted in total 0.80 of weight over the total of 1. Also, the following indicators are established as key in measuring performance: Time allocated for the preparation of tender, Advertisement total duration, Number and Nationalities of Bidders, Publicity frequency, Time Performance Index, Number of complaints or litigations generated, Cost Estimate Accuracy, Publicity extent, and Number of approvals and controls performed, etc. The study concludes that public contract award process must be transparent, fair, competitive, and complies perfectively with rules and procedures to achieve likely above 80% of the expected performance.

Keywords: Performance criteria, Measurable Indicators, Public works contracts, AHP, Chad

Cite this paper: Sazoulang Douh, Theophulus Adjei-Kumi, Emmanuel Adinyira, Bernard Baiden, Criteria and Measurable Indicators for Assessing the Performance of Public Works Contract Award Process in Chad, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 3 No. 2, 2014, pp. 57-64. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20140302.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Performance is the effectiveness of the way of doing something and according to Maylor (2003), performance is not conformance and has shifted to excellence and expressed as: what is the shortest possible project duration, what is the lowest cost and what is the highest level of quality that can be achieved. For instance in the production field, performance level equals the standard time for an activity when directly compared with the actual time spent on the task (HarisandMcCaffer, 2001). Therefore, performance is not an end in itself but a means to appreciate if the organization or the process is effective and efficient. Performance measurement has been defined from different perspectives by different researchers but there is a lack of agreement on a single definition argued Khan and Shah (2011). However, Bourne et al. (2003) asserted that performance measurement is an integral part of the management planning and control system of the organization or process being measured. In addition, Franco-Santos et al. (2007) found that there is an agreement among researchers on the two following features: performance measurement is a multi-dimensions system used to quantify the efficiency and effectiveness of an action and is a means to achieve certain pre-defined organizational goals and objectives. According to Strand et al. (2011), performance cannot be directly measured unless we use a number of quantifiable standards, attributes, proxies, measures, criteria or indicators on the basis of which we make inferences about the relative performance. Unfortunately, a major problem in performance measurement is the selection of appropriate criteria or indicators because identifying the wrong indicators or leaving out relevant ones can also mislead the assessment (Hatry, 1999). So, indicators should be chosen smartly. The study therefore aims at establishing relevant criteria and related quantifiable indicators that contribute objectively to the performance assessment supporting decision making when awarding public works contracts.

2. Literature Review

- The prime performance assessment of construction has been generally the extent to which client objectives like cost, time and quality were achieved (Kagioglou et al., 2000). Inaddition, clients of the construction industry want their projects delivered on time, on budget, free from defects, efficiently, right first time, safely, by profitable companies (United KingdomKPI Working Group, 2000). Unfortunately, these indicators are criticized of being mostly centered on client’s interest and are hence insufficient to capture the overall performance of construction projects which are complex in nature. In the effort of establishing balanced and leading performance indicators specific to the construction industry, some researches were undertaken in order to determine Key Performance Indicators (KPI), relevant criteria and related quantifiable measures which are briefly discussed below.

2.1. Key Performance Indicators in Construction Industry

- As result of researches, an unknown Author (2010) identified 30 KPIs grouped into three categories comprising ten indicators each. First, the Economic KPIs are following: Client Satisfaction – Product, Productivity, Client Satisfaction – Service, Safety, Profitability, Defects, Cost Predictability of Project, of Design, of Construction, and Time. Second, the Respect for People KPIs comprise: Employee Satisfaction, Qualifications and Skills, Staff Turnover, Equality and Diversity, Sick Absence, Training, Safety, Pay, Working hours, and Investors in People. Lastly, Environmental KPIs include: Impact on the environment – Product and Construction process, Energy use (Designed) – Product, Energy use – Construction process, Mains water use (Designed) – Product, Mains water use – Construction Process, Waste – Construction process, Commercial vehicle movements – Construction Process, Impact on Biodiversity – Product and Construction process, Area of habitat Created/Retained – Product, and Whole Life Performance – Product. In addition, Huyssteen et al., (1995) established two groups of indicators. Economic indicators include Contribution to Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Growth, Investment, Production prices, Building plans passed and Buildings completed. And Project indicators are Site safety, Participation of previously disadvantaged individuals, Defects, Non-price-only tenders, Training, Cost Predictability, Time Predictability, Use of modern forms of contract, and Client satisfaction. Besides, Hoover and Schubert (2007) have established 9 KPIs that successful construction firms should monitor. These are Liquidity, Cash flow, Labor productivity, Schedule variance, Margin variance, Un-approved change orders, Committed cost, Backlog, Customer satisfaction/scorecard. From the foregoing list, it appears clear that most indicators are developed from construction companies’ views and perspectives, public administration and other participants or stakeholders are not well taken into account. On the contrary, this long list of KPIs rather indicates the complexity of the issue of performance measurement using both leading and lagging balanced criteria/indicators in construction industry. This leads to the review of criteria that are relevant in characterizing specifically the performance of public contract award process.

2.2. Performance Criteria in Public Procurement (PP)

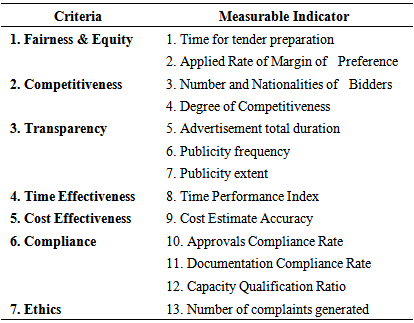

- According to Williams-Elegbe (2007), the goals of PP may be listed as competition, transparency, integrity, best value and efficiency. Watermeyer (2011) lists the primary objectives of a procurement system as fairness, equity, transparency, competition and cost-effectiveness. According to the World Bank (2003), a PP system can be said to be well functioning if it achieves the objectives of compliance, transparency, competition, economy and efficiency, fairness and accountability. It has also to demonstrate efficiency and economy in cost and time added Oladepo (2000). In order to achieve all these goals and objectives, procurement system must be well organized, carried out correctly with regard to quantity, quality and timeliness, and at the optimum price; above all in accordance with the appropriate guidelines, principles and regulations concluded Dikko (2000). In an analysis of PPsystem in South Africa, Pauw et al. (2009) have established five following criteria: fairness, equitableness, transparency, competitiveness and cost-effectiveness. Strand et al. (2011), also identified three main criteria: total costs of public procurement processes, competitiveness, and time efficiency. Further in Uganda, Public Procurement and Disposal of Public Assets Authority has used four following criteria to assess the public procurement: procurement planning, procurement records, procurement cycle time and compliance to laws and regulations (Uganda Public Assets Authority, 2007).From the above assertions and considering PP objectives established by many developing countries, following criteria are identified as relevant in assessing the performance of procurement system: Ethics, Competitiveness, Compliance to laws & regulations and conformity to rules and procedures, Transparency and public Accountability, Fairness and Equity, Time Effectiveness, and Cost Effectiveness. However, it appears that these criteria are interrelated and interdependent and it is often not possible to achieve good performance with each of them isolated. Rather their combination will give better performance. Based on the seven criteria identified above and listed in the first column of the Table 1 below, one or more related indicators are listed in the second column. In fact, these indicators are the quantifiable measures that qualify, interpret or represent the most these criteria. In total, thirteen (13) indicators were identified and fully described in results discussions section in next pages.

|

3. Method

- The study adopted a quantitative approach with questionnaire as data collection instrument using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) approach. Respondents are asked to pair-wise compare the identified 7 criteria and 13 indicators using a simplified AHP scale of 5 points: 1 = Equal Importance, 3 = Moderate importance, 5 = Strong importance, 7 = Very strong, and 9 = Extreme Importance (Saaty, 2000). The targeted population comprises 60 structures including public procurement entities, consulting firms, contractors and sponsors, and was considered as sample. Data analysis is done by an adapted AHP methodology involving five steps: (1) Identification of criteria and related measurable indicators, (2) Construction of AHP Hierarchy, (3) Collection of pair-wise comparisons from respondents and Verification of the Consistency of respondents, (3) Computation of Geometric Means of the consistent ratings and construction of a single pair-wise comparison matrix (Saaty, 2008), (4) Computation of relative weights of Criteria and Indicators with Consistency Ratio (CR)verification, (5) Computation of Composite Weights and ranking of Key Indicators (Kunz, 2010).Out of the 60 questionnaires administered, 38 valid completed questionnaires were returned representing 63.32%. Even though the global rate of consistency test seems law with 42.11%, the majority of respondents (60.52%) are construction professionals, highly qualified and very experienced. Moreover, the Consistency Ratios (CR) varying from 0.00 to 0.055 (< to 0.10) are indicating that respondents were very consistent. Besides, after the computation of the relative weights of criteria and indicators, a validation process was performed using Experts Approach. More than 70% of participants strongly agree on the relevance of these findings. Therefore, it can be concluded that results represent the point of view of qualified and experienced construction professionals and are considered valid.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Main Results

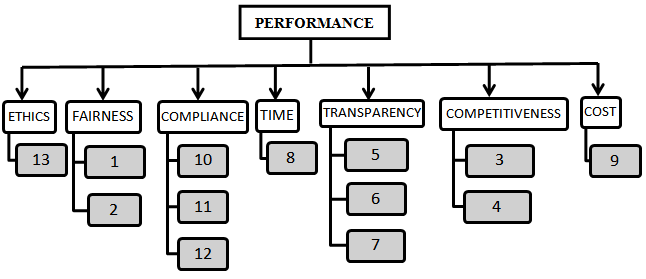

- As mentioned in the adopted method above, the combined AHP hierarchy constructed for Criteria (high level) and Indicators (low level) is as follows in Figure 1 below. Note that numbers in boxes represent the ranking of established indicators as listed above.

| Figure 1. Combined AHP hierarchy for Criteria & related Indicators |

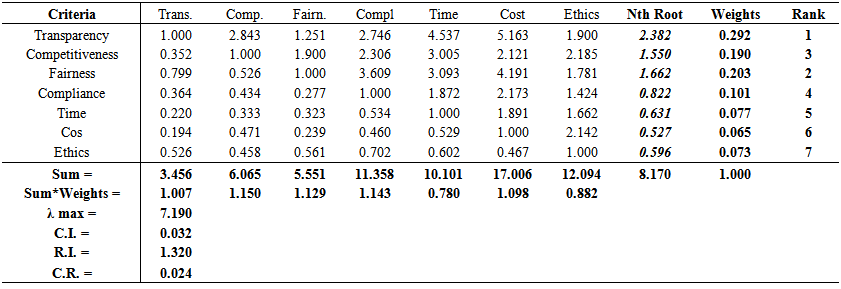

| Table 2. Relative Weights of Criteria |

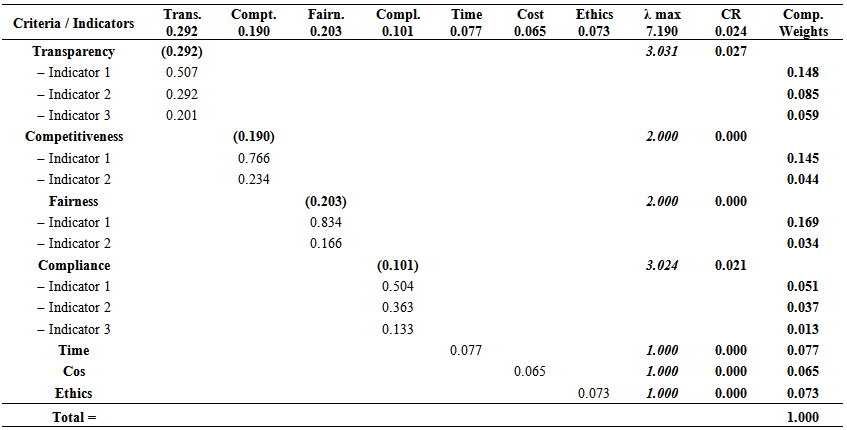

| Table 3. Composite weights of relevant Criteria with measurable Indicators |

|

4.2. Relevant Criteria and Related Key Measurable Indicators

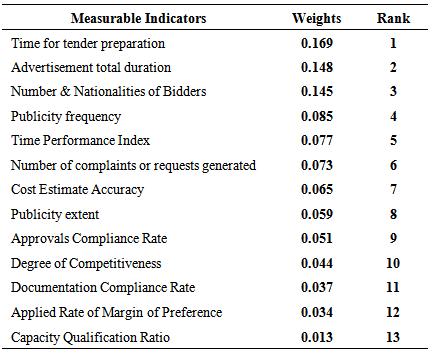

- Considering Table 2, the high ranked criterion is Transparency with 0.292 of weight followed by Fairness and Competitiveness with 0.203 and 0.190 respectively. These three criteria put together weighted about 0.685 being almost 70% of the performance. Compliance has gained 0.101 and occupies the fourth rank. The scores of Time and Ethics are 0.077 and 0.073 respectively whereas Cost is the last with only 0.065 indicating probably that cost factor is of less relevance at pre-contract stage. However, assuming that all the identified criteria were of equal weight, that means each would have 1/7 = 0.1428. Based on the above scores as compared to the assumed average weight, it can be concluded that the most relevant criteria are in order of importance transparency, fairness and competitiveness. Applying the same rule to indicators, the assumed average weight would be 1/13 = 0.077 and from Table 6.12 above, key measurable indicators are in following order of importance Time for tender preparation, Advertisement total duration, Number and Nationalities of Bidders, Publicity frequency, Time Performance Index. The above relevant criteria as well as the related indicators are simultaneously discussed below.

4.2.1. Transparency and Public Accountability

- The high ranking of Transparency (including public accountability) with 0.292, means that it contributes almost 30% to the achievement of contract award process performance. This is perfectly in line with the core principles of Public Procurement systems stipulated in national procurement Acts where transparency and fairness are always listed first. This is also corroborated by Dos Santos et al., (1998) who state that transparency and public accountability are foundations of excellence and pillars of competitive construction companies. Another explanation of this high score is that public accountability and transparency help to detect early any deviation from fair and equal treatment, and make such deviation less likely to occur hence protecting the public interest (Appiahand Moro, 2011). Moreover, transparency prevents fraud and corruption as stated Steven and Patrick (2006) and, hence improves performance of Public Procurement.Not surprisingly, among the three indicators related to transparency, two occupy the second and fourth positions respectively (i.e. Advertisement total duration with a weight of 0.148 and Publicity frequency with 0.085). Even the last indicator (i.e. Publicity extent) holds the eighth position supporting the high position of transparency and public accountability. From the foregoing, it can be concluded that transparency is the most relevant criterion in improving the performance of public contract award process in Chad. However, although transparency has been revealed as the most relevant criterion, it has also been the most difficult to practice on the ground as far as public procurement is concerned. For instance, it is consistently reported that tendering processes lack transparency due to the fact that procurement information are often hidden and difficult to access by the public (OECD/DAC, 2005; CCSRP, 2010). The worse is that even when the process seems transparent, its effectiveness and efficiency do remain questionable because it is not easy to access the genuine data to form a basis for a challenge or protest results because procurement officers hardly disclose any information. Concerning public accountability, it is rare that the public is informed except when some deficiencies in transparency are disclosed and this is always too late to remedy. Therefore, owing to the prominent role transparency plays in Competitive Tendering Process, it is recommended a special attention to it if governments are willing to achieve success with good performance in Public Procurement.

4.2.2. Fairness and Equity

- Having won the second place with 0.203, Fairness and Equity couple confirms their privileged position in procurement laws like transparency. First of all, fairness suggests that the procurement procedure is conducted in an open and impartial manner and is consistent and therefore reliable (WB, 2003). Then fairness is closely related to justice or getting what you deserve; otherwise contracts are awarded mainly on merit (John, 2001). Whereas Equity means equal access, equal opportunities, and equal treatment to all potential contractors and also focuses on the promotion of secondary objectives (David, 2007; Shakeel, 2010). Most often, equity is applied when equal shares are not fair and allows a special allocation of opportunities to qualified but disadvantaged contractors (Watermeyer, 2013). For instance, Equity can be used to generate business and employment opportunities for indigenous firms, women or youth through construction projects (e.g. in South Africa during the post-apartheid period). Moreover, Fairness in addition to Equity deserve this high score and not only that, the first established key Indicator (i.e. Time for tender preparation) is found under this criterion supporting its importance. Finally, it appears clear that ‘Fairness and Equity’ is a second relevant criterion in influencing positively the performance of public contract award process in Chad. However, like transparency, ‘Fairness and Equity’ is another problematic issue in Public Procurement. According to Strand et al. (2011), full Fairness implies total absence of bias, what is undoubtedly very difficult to achieve in Chad where fraud and corruption have invaded the procurement systems at all levels. Worse of all, these malpractices are rather reducing fairness and transparency as they are among challenges identified by Douh et al., (2013). As result, many complaints are still on the rise aggravating the loss of trust in the PP system in Chad.

4.2.3. Competitiveness

- According to GOJ (2008), competition is the cornerstone of public sector procurement and the primary driver of Value for Money. In addition, competition has many other benefits including hampering corruption (Steven and Patrick, 2006), reducing cost by broadly 20% (Simon et al., 2005) and providing the enabling environment for effective utilization of scarce resources in the economy (Dikko, 2000). Furthermore, it gives a good image of the public governance (David, 2007) and underpins fairness and transparency. Based on that, the third position occupied by Competitiveness with a weight of 0.190 is certainly an additional proof of its relevance. Consistently enough, one of the related indicators namely Number and Nationalities of Bidders has gained the third rank with 0.145 confirming the opinion of Arrowsmith (2011). According to him a project that receives a large number of bids will result in selecting a capable contractor at more competitive price. Besides, a tender that attracts a significant number of foreign bids indicates that the process is reliable and worthy to be trusted stated Williams-Elegbe (2007). For all these reasons, it is simply logical that competitiveness deserves its rank and considered as a relevant performance criterion as far as Public Procurement is concerned in Chad.

4.2.4. Compliance

- Compliance is the fourth relevant criterion with a score of 0.101 ahead of Time, Cost and Ethics. This good position is comforted on one hand by the lack of law enforcement that has been one of the weaknesses of the national Public Procurement Acts in developing countries (Banfo-Agyei et al., 2013), and on the other hand by the fact that a related Indicator (i.e. Approvals Compliance Rate) is among the key ones. Besides, in a previous study, Douh et al. (2013) have identified the lack of compliance to laws and regulations as second major challenge facing the implementation of Competitive Tendering Process in Chad. As matter of facts, most of developing countries have put in place good laws and regulations but are incapable to ensure proper enforcement and full application. It is frequent that procurement officers do disrespect laws and rules in procurement operations without punishment in Chad (CCSRP, 2009 & 2010). Yet, be compliant with time limits offers double advantages: tenderers are satisfied when they receive tender results on time, what enables those who failed to go for other opportunities and the successful to start business; and procurement officers also are satisfied of being effective in their mandate improving surely the image of public service. Obviously, full compliance to procurement laws and regulations is a relevant criterion despite weaknesses mentioned above.

4.2.5. Other Criteria

- Other criteria are Time, Ethics and Cost in order of importance. Although these criteria do not gain high scores, their related indicators are critical to some extent to the achievement of a high level of performance. For example, time related indicator like ‘Time Performance Index’ occupies the fifth rank with 0.077 immediately followed by the Ethics’ related indicator’s (i.e. Number of complaints or requests generated) with 0.073. Another finding that comes to light is the predominance of indicators involving time that are ranked high [Time for tender preparation (1rst), Advertisement total duration (2nd), and Time Index Performance (5th)] indicating that timeliness is an important effectiveness indicator as far as Competitive Tendering is concerned in Chad. For instance, public administration is well known for its bureaucracy and most often, procurement officers do delay expressly tender announcements to favour their candidates to the detriment of others of good standing. Moreover, timely performance of tendering activities indicates time effectiveness and demonstrates compliance at the same time. Therefore, time indicators are key contributors to high performance. The last but not the least is Ethics criterion that does not receive the expected attention from respondents. Indeed, one of the ills of the procurement officers is the lack of ethical conduct especially when it comes to integrity and confidentiality in Public Procurement transactions. Finally, regarding Cost criterion, it is found that respondents do not consider cost effectiveness as a real preoccupation at pre-contract stage even though cost has always been an important criterion in construction industry (EU/ECORYS, 2011). This revelation has to be investigated in further study. In the light of the above, it can be concluded that the most relevant criterion is Transparency followed by Fairness and Competitiveness. This order agrees perfectively with the position of Appiah and Moro (2011). Therefore, an effective Competitive Tendering Process has to be transparent, fair and competitive to achieve at least 70% of the expected level of Effectiveness. When, the whole process complies perfectively with rules and procedures, the likelihood of high performance is above 80%. In other words, a transparent process will surely enhance competitiveness, fairness and equity. Thereby when transparency, fairness and equity are secured, competition is inevitably promoted. As matter of fact, competition enables economy in cost and time and hampers corruption as well. That can be achieved if and only if the process is conducted by people with high ethical behaviour. Hence, it appears clear that all these criteria are interrelated and interdependent as demonstrated by the ranking of related indicators that do not follow the same pattern like criteria. Besides, in the effort of establishing balanced and leading performance indicators specific to the Public Procurement in Chad, following key indicators are established: Time for tender preparation, Advertisement total duration, Number & Nationalities of Bidders, Publicity frequency, Time Performance Index, Number of complaints or requests generated, Cost Estimate Accuracy, Publicity extent, and Approvals Compliance Rate. The characteristics of indicators (number, simplicity, cost and timely effectiveness, easiness of application and data gathering, etc…) are perfectly in line with the performance indicators established by Neely et al. (1997) and Matthews and Gibson (2009). Additionally, the study reveals that indicators involving time are ranked high suggesting that time management has to be addressed properly during the tendering process whereas cost was of little interest at this stage.

5. Conclusions

- At the light of the above exposition, it can be concluded that the heaviest criterion is Transparency followed by Fairness and Competitiveness. This order complies perfectively with the literature. In the effort of establishing balanced and leading performance indicators specific to the PP in Chad, following key indicators are established: Time for tender preparation, Advertisement total duration, Number & Nationalities of Bidders, Publicity frequency, Time Performance Index, Number of complaints or requests generated, Cost Estimate Accuracy, Publicity extent, and Approvals Compliance Rate. Subsidiarily, the study reveals that indicators involving time are ranked high indicating that time factor has to be handled carefully during the tendering process whereas cost was of little interest at this stage.Consequently, Competitive Tendering Process has to be transparent, fair and competitive to achieve at least 70% of the expected level of Effectiveness. When, the whole process complies perfectively with rules and procedures, the likelihood of high performance is above 80%. In other words, a transparent process will surely enhance competitiveness, fairness and equity. Therefore when transparency, fairness and equity are secured, competition is inevitably promoted. As matter of fact, competition enables economy in cost and time and hampers corruption as well. That can be achieved if only if the process is conducted by people with high ethical behavior. Hence, it appears clear that all these criteria are interrelated and interdependent as demonstrated by the ranking of related indicators that does not follow the same partner like criteria. Having found that respondents do not consider cost effectiveness as a real preoccupation at pre-contract stage even though cost has been always an important criterion in construction industry; so, the study recommends that this revelation be further investigated in the future.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML