-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2014; 3(2): 47-56

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20140302.02

Identifying the Preferred Leadership Style for Managerial Position of Construction Management

Younghan Jung1, Myung Goo Jeong1, Thomas Mills2

1Department of Civil Engineering and Construction Management, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA 30460

2Department of Building Construction, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, 24061

Correspondence to: Younghan Jung, Department of Civil Engineering and Construction Management, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA 30460.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The construction industry is multidisciplinary by nature, operating within many boundaries and collaborating closely with many players, including designers, constructors, owners, and government agencies. Project and organization success depends on well-developed interpersonal skills working at different hierarchy levels to meet varying leadership and performance demands. Leadership styles can be represented with differing combinations of three main decision-making styles: 1) Autocratic, 2) Participatory, and 3) Free-rein. This study hypothesizes that varying managerial positions require different combinations of leadership styles to achieve high levels of performance and successful career. This study surveys eighty-two project executives and managers to identify their preferred leadership style for construction managerial positions. The statistical results indicate that both project executives and managers prefer to have more autocratic managers and superintendents at project manager positions and a more participatory leadership for project executives. Demographic factors surveyed, also include current executive and manager levels of education, length of employment, and leadership program attendance to understand the career path of a managerial position in construction.

Keywords: Leadership, Construction Professional, Decision-Making, Construction Management

Cite this paper: Younghan Jung, Myung Goo Jeong, Thomas Mills, Identifying the Preferred Leadership Style for Managerial Position of Construction Management, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 3 No. 2, 2014, pp. 47-56. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20140302.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Good leadership is essential if a company is to achieve high levels of performance and implement a culture of productivity improvement. The construction industry, especially construction project management, is multidisciplinary by nature and successful project completion requires the contributions of many players, including designers, constructors, owners, and government agencies, all of whom initiate requirements and collaborate closely with each other [1]. Construction professionals and subsequently construction organizations benefit from employing individuals with well-developed interpersonal skills that smooth the way when dealing with the many different stakeholders and at different levels within the company hierarchy. The use or misuse of these skills during project execution impacts project performance outcomes either positively or negatively. Consequently, a successful executive is generally pictured as possessing intelligence, imagination, initiative, the capacity to make rapid (and generally wise) decisions, and the ability to inspire subordinates [2]. Construction firms specialize by residential, commercial, industrial, and heavy and highway construction. The term “construction manager” who is responsible for project management describes project leaders but is used loosely without consistently accepted definition [3] due to the uniqueness of project type and delivery system. However, in general, construction industry managerial and/or supervisory positions can be classified hierarchically into specific job categories: 1) project executive, 2) project manager, 3) superintendent, 4) office engineer, and 5) field engineer. In 1939 Kurt Lewin led a group of researchers to identify different styles of leadership [4]. This early study has been very influential and established three major leadership styles: 1) Autocratic, 2) Participatory, and 3) Free-rein [5]. The two extremes of this spectrum are the autocratic pattern type, which is a manager- or boss-centric leadership style, and the free-rein pattern type, which is a subordinate-centric leadership style. Between these extremes is the participatory pattern type that incorporates both these leadership patterns, allowing subordinates to be involved in decisions while also benefiting from the manager's input. The optimum degree or combination of leadership styles varies for each managerial position, and different levels of managerial positions have unique and dominant leadership patterns beyond the traditional contributory responsibility for efficient and effective project management [1]. Often overlooked outside the industry is that modern construction management processes involve complex financial matters and demanding interpersonal skills, with managers engaged in activities such as bidding, cost control, labor and contract negotiations, project planning, and so on. Unlike a managerial position in the manufacturing industry, construction professionals must deal with a wide range of tasks and processes for each construction project. Managerial personnel in the construction industry not only supervise subordinates in their own organizational hierarchy but also provide purpose, direction, and motivation to contracted crafts people working for trades sub-contractors. The need for improved leadership skills in the Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC) industry is gaining attention. In January 2001 ASCE began a new quarterly publication titled Leadership and Management in Engineering. At the June 2003 Top1000 Contractors Leadership Forum 2003, industry leaders stressed the need to “push responsibility down” and “develop leadership teams” [6]. Like other efforts, the objective of leadership development is not solely focused on the ability to satisfy conflicting requirements in support of organizational success, but also the ability to successfully grow professional careers.

2. Study Objectives and Overview

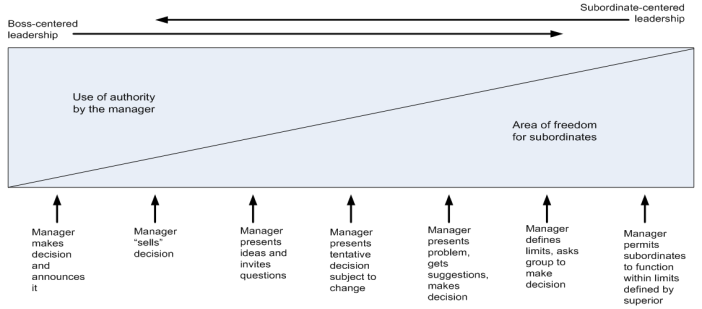

- The main objective of this study was, based on using the experiential perspectives of the project manager and project executive, to identify preferred leadership behaviors of those individuals holding managerial and supervisory positions in construction management. Data obtained from this study will contribute to advancing the study of position specific managerial leadership development linked to factors, including job responsibility, hierarchical relationship within the organization, and contractual relationship beyond the organization. The survey results were addressed based on Tannenbaum and Schmidt’s (1973) continuum of leadership behavior as shown in Figure 1 [2].

| Figure 1. The Continuum of Leadership Behavior (Adopted from Tannenbaum and Schmidt, 1973) |

3. Literature Review

- The topic of leadership attracts instant attention among those in charge of business organizations, conjuring up images of powerful, dynamic individuals who command victorious armies or direct corporate empires. However, serious academic studies of leadership failed to emerge until the twentieth century [7]. One of the first scientific studies of leadership was initiated by Kurt Lewin [8], who led a group of researchers seeking to identify different leadership styles. Goetsch and Davis (2006) mentioned five leadership styles in quality management for production, processing, and services: autocratic, participative, democratic, goal-oriented, and situational leaderships [9]. An autocratic leader makes a decision and announces it. In this case, the manager identifies a problem, considers alternative solutions, selects the one he or she considers most appropriate, and then reports this decision to subordinates for implementation [2]. In contrast, participative leadership involves the use of various decision procedures that allow other people to influence the leader’s decision, including consultation, joint decision-making, power sharing, and decentralization [7]. Democratic or Free-rein leadership is the indirect supervision of subordinates, allowing others to function on their own without extensive direct supervision. Subordinates are allowed to prove themselves based upon performance rather than meeting specific supervisory criteria [10]. This is the ultimate self-managed team. While these three leadership styles (autocratic, participative, and democratic) show very distinct characteristics, the last two styles (goal-oriented and situational) use a combined leadership among the first three styles to achieve a goal or to resolve a situation [9]. Mendez et al. (2013) also used the three leadership styles in their research in identifying the most effective leadership style found in small construction businesses in Mexico [11]. With 49 samples, their statistical analyses showed liberal leadership styles such as democratic or free-rein were more effective, whereas the autocratic leadership was found to be less effective for small construction businesses. Mendez et al. (2013) claimed that the results were consistent with other similar studies conducted for the small construction businesses.Toor and Ofori (2008) focused on the authentic leadership in the construction industry to emphasize the need for authentic leadership development for construction professionals [12]. The authentic leaders can be described as a leader, who uses his /her personality and character, leads with heart, and shows high level of self-discipline [13]. Toor and Ofori (2008) assert that the project managers in the construction industry need to develop the authentic leadership style to overcome challenges and to successfully operate the complex construction projects [12].Transactional and transformational leadership styles that was originally developed by Burns (1978) and advanced by Bass (1985) have been also applied in the study of construction industry leadership style [14, 15]. Giritli and Oraz (2004) utilized the transactional and transformational leadership styles and their six components (coercive, authoritative, affiliative, democratic, pacesetting, and coaching) in order to identify the leadership styles observed in Turkey [16]. Chan and Chan (2005) also used the similar leadership styles to evaluate them among building construction professionals in four countries (Australia, China – Hong Kong, Singapore, and United Kingdom) [17]. In this study, it was found that the transformational leadership with a major factor of “Inspirational Motivation” is more frequently used in the construction industry [17].Decision-making is directly relevant to all the processes inherent in interpersonal and social leadership [18], largely because making decisions is one of the most important functions leaders perform [7]. Many of the administrative activities performed by managers, especially among construction professionals, involve making and implementing decisions, including the selection of subordinates, resolving conflicts between different stakeholders, and dynamically handling changes. Leadership is not about the individual manager's personality, although this inevitably affects their style, but their behavior [19] and is primarily aimed at boosting organizational activities both efficiently and effectively. The construction industry has its share of research concerning teamwork and leadership [20].In every company and across many different disciplines, each managerial position requires different decision-making (leadership) behaviors. Tannenbaum and Schmidt (1973) suggest a continuum of leadership behavior that describes how a manager can manipulate the degree of authority and the amount of freedom available to his subordinates in reaching decisions within the three major leadership styles, as shown in Figure 1 [2]. Actions towards the left of the graph are characteristic of autocratic decision-making, while actions toward the right represent managerial positions that maintain a low degree of control, allowing subordinates free-rein to make decisions themselves. Project participants in the construction industry primarily consist of owners, designers, and constructors. Owners can be individuals seeking a home for their growing family, a large organization responding to a change in technology, a municipality seeking to improve its infrastructure, or a developer working to make money by filling a perceived market need [21]. Designers are the architects and engineers who produce the principle designs on which the construction projects are based. Constructors have responsibility for all the actual construction activities, including those performed by sub-contractors, specialty constructors, individual building trades, suppliers, and so on. From the perspective of the organizational hierarchy of a construction project, project-related positions can be broken down into project executives, project managers, office engineers, superintendents, and field engineers, and these positions are mainly project-related. Each position has unique responsibilities and makes contributions to different areas at different times under different situations using different decision-making skills. Every discipline requires its managers to carry out broadly similar duties, though the precise nature of those duties will depend on the company's business. For instance, an engineer or architect normally manages projects associated with designing specialized equipment or structures [22]. In the construction industry, although some responsibilities are duplicated by job category, each managerial position deals with different participants in support of the construction project and construction organization goals. Therefore, construction professionals need specialized interpersonal skills and leadership behaviors, especially when it comes to decision-making in the different managerial position. A problem solution or decision is intrapersonal and interpersonal. Most direct relevance to processes of leadership is the interpersonal or social aspects of decision-making [18]. Decision-making behaviors are also directly related to the individual's professional achievement in his or her career.

4. Research Methodology

- To identify the leadership style considered appropriate for each managerial position from the perspectives of the project executives and managers, as well as the career path of professional achievement in construction professionals, this study used a three step approach: (1) design a survey tool to gather sample population demographics and response data on preferred leadership style for a specific managerial position; (2) assimilated data collection for qualification, and (3) analyze the collected data and report the results.

4.1. Design the Survey Tool and Develop the Questionnaire

- This survey tool was designed in two parts: 1) Informative Questions and 2) Best Leadership Style Questions. The survey questions were structured with closed-ended formats and included the partial application of Likert-scale, categorical, and multiple-choice formats. Informative questions were used to find the general career path and the relationship between leadership style and professional achievement based on the educational and industrial backgrounds of the pool of construction professionals.The survey questions on Best Leadership Style were designed to determine preferred leadership styles in each managerial position using the three major decision-making leadership behaviors: 1) Autocratic, 2) Participatory, and 3) Free-rein. To analyze an in-depth stratification of leadership styles a scale similar to that used for the Continuum of Leadership Behavior [2] was adopted with the identical seven different levels as shown in Figure 1. The questionnaires allowed participants to select from among seven different leadership levels made up of subdivisions of the three major behaviors for 1) their own leadership style and 2) what they considered ideal for each of three managerial positions: superintendent, project manager, and executive.

4.2. Sample Selection and Distribution

- The sample pool consisted of 174 construction professionals and employees in full time positions at 90 companies primarily located in the southeastern United States. The sample pool was composed of contractors, subcontractors, engineering professionals, and consultants. To maximize the response rate, the distribution of survey questionnaires was conducted individually and accompanied with a personal explanation and a request to return completed questionnaires. Table 1 summarizes the survey response rates. Survey questionnaires were distributed to the construction professionals attending a construction career fair and collected by the researcher after the event. Of the 174 survey questionnaires distributed, 94 were returned for a 54% response rate.

4.3. Data Collection and Qualification of Responses

- To qualify responses for data analysis, researchers examined these respondents’ answers with two critical standards, 1) whether the respondent had provided or completed the basic information section, and 2) whether the answers to the questions were nonsense or illogical. Five respondents failed to complete the informative questions for the demographic analysis and seven respondents answered questionnaires illogically. For instance, one respondent completed the questions on current position, years in current position, and years in the construction industry by answering "project executive", "1 year", and "1 year", respectively. Incomplete demographic data and illogical responses disqualified 12 returned surveys. The remaining 82 respondents, 47% of the distributed surveys, were therefore used for the data analysis to justify an appropriate leadership style for a managerial position, as shown in Table 1.

5. The Reflection of Leadership by Positional Duties

- To emphasize the distinctive characteristics among the three managerial positions: Project Executive, Project Manager, and Superintendent, this section summarizes the typical job duties of each position. This comparison of job functions for each managerial position will provide a clear understanding of details of what is needed to fulfill different leadership styles.

5.1. Project Executives

- In general, a project executive deals with department managers, project managers, and clients to achieve the organization’s goals. Examples of these duties are:● Procure construction opportunities for the company by managing the company's relationships with existing clients● Provide overall leadership and direction on construction projects with different departments within the company● Establish, promote and maintain a mentoring relationship with all members of the company ● Ensure the quality, profitability and success of projects by making sure all deliverables are completed on time and within budget● Maintain pro-active and communicative relationships with clients and key project personnel

5.2. Project Managers

- In general, a project manager (PM) deals with project owners, project related department managers, superintendents, subcontractors, and field staff to deliver a successful project and is responsible for the safe completion of his or her projects within budget, on schedule. At the same time the PM must meet the company's and customer’s quality standards, deliver value and satisfy their customers or clients. It is his or her responsibility to initiate any action required to achieve these objectives and to ensure that all project activities comply with both the contract documents and company policies. The Project Manager's duties will vary as required to support the Project Superintendent and other personnel assigned to the project and are likely to include: ● Planning: coordinate plans and supervise field staff, subcontractors and craft activities for the entire project● Operations: liaise with other department managers to ensure all required materials, equipment, and inspections support the project schedule● Scheduling: oversee job scheduling, maintain a Job in Progress Report, establish the project schedule and update it as required● Control: communicate with field managers to ensure efficient and productive work

5.3. Superintendents

- On final insight gleaned from the job responsibilities involves the role of project superintendent and their preferred leadership style. A general superintendent deals with project managers, foremen, suppliers, and field staff to manage personnel and materials on the job site and coordinate schedules, safeguarding the company's profit margin. The superintendent is the company's representative on site, with the responsibility and authority for daily coordination and direction of the project. He or she ensures a safe job site and that the project aligns with scope, budget, schedule, quality and other project requirements. To accomplish this, the superintendent produces a day-by-day plan for the construction project and ensures that daily and weekly activities are consistent with this plan via the following general activities:● Supplies information to accounting department so that records of costs can be maintained● Keeps constant check on all trades, overseeing workmanship and materials● Supervises personnel both directly and indirectly through the foremen

6. Analysis of Survey Responses

- Data was extracted from the qualifying responses and divided into four construction organizational business categories, each of which was analyzed separately. The categories used were general contracting (45%), design/build (24%), specialty contracting (11%), and other businesses (20%), as shown in Table 2.

|

|

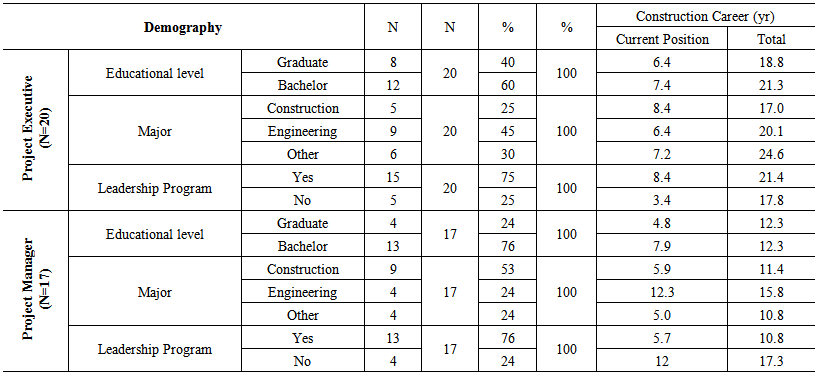

6.1. Demographic Analysis of Higher Managerial Positions

- The first part of the questionnaire asked for the respondent's career standing within the construction industry in order to determine whether years of experience, seniority within the company, or educational background were related to the respondent's perceptions of the type of leadership style and professional achievement required for managerial positions. These informative questions provided a general picture of the level of career achievement for the respondents, ranging from entry level positions to company executives. Appendix 1 shows the summary of the demographic analysis for project executives and managers, presenting the distribution of their educational levels, majors, and whether they participated in leadership programs. It should be noted that this analysis did not include data for superintendent due to limited sample collected.According to the data, respondents working as project executives and project managers in the construction industry had an average of 19.4 years and 12.0 years, respectively, of construction industry experience. They had held their current position as a project executive or project manager for an average of 6.2 years and 7.2 years, respectively. Based on the demographic data shown in Appendix 1, the typical career path in the construction industry recognizes broadly the progresses from a college graduate to an executive. A college graduate with a bachelor's degree majoring in construction or engineering may start their career as a field engineer or office engineer position in the construction industry. After 5 years or so they are likely to have gained sufficient experience to become a project manager, and within an average of 13 years to become a project executive. One third of those occupying the higher managerial levels have participated in leadership programs, 75% of project executive levels and 76% of project manager levels. This rate can be assumed to be reflective of the importance leadership training has in the construction industry. Of the self-reported project managers 24% had graduate degrees, increasing to 40% for those at the executive level.

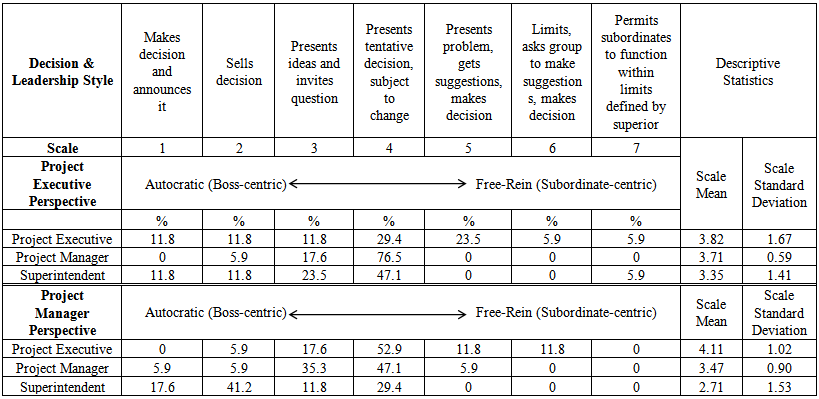

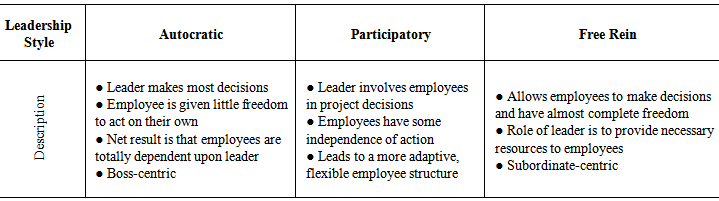

6.2. Best Leadership Style

- The second part of the questionnaire designed to examine the respondents’ perspectives of “Best Leadership Style,” at each construction industry managerial position. Due to the limited sample pool, these results are primarily from the project executives and project managers’ point of view. Because project manager’s leadership style influences project success [23], it is surmised that individual project manager/executive experiences reflect the appropriate leadership style and offer support for future study. To minimize misunderstanding of leadership styles and align responses, a description was provided of the three main leadership styles, Autocratic, Participatory and Free-rein, in Table 4, and each respondent was asked to assess how effective each type of decision-making would be for each level of managerial position, especially project executive, project manager, and superintendent.

| Table 4. Description of Leadership Style Used in Survey Questionnaire |

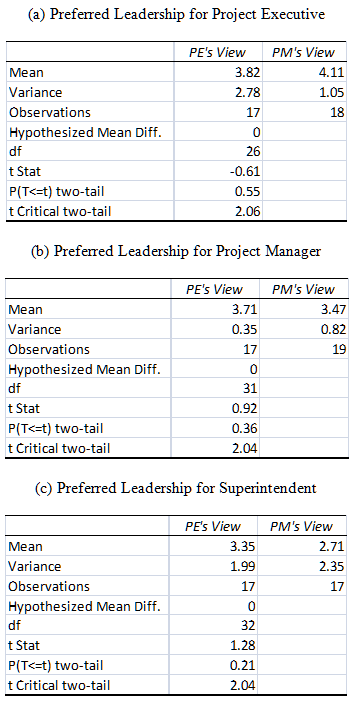

6.2.1. Preferred Leadership Style for Project Executive

- Project executives generally have trusted relationships with others, and it evidences itself in presenting a combination of boss-centered and subordinated-centered leadership trending toward to a more intensive participatory leadership style.The scale mean values are close to the mid value of the scale which is 4 (3.82 from project executive and 4.11 from project manager). In the participatory leadership, the leader provides a flexible and adaptive environment to employees in the decision making process. Although the leader allows employees to be independent of making decision, the problem identified by the leader is presented to the subordinates. In other words, the leader involves the whole process of decision-making and encourages the subordinate to suggest solutions. In this way, the project executive can establish a mentoring relationship with all members of the company.To visualize the survey results with continuous distribution curves, two statistical distribution curves (Normal and Gamma distributions) were drawn based on the mean and standard deviation values. Figure 2 presents two charts where the left and right side charts represent the preferred project executive leadership from an executive and manager’s point of view, respectively.

| Figure 2. Preferred Leadership Style for Project Executives |

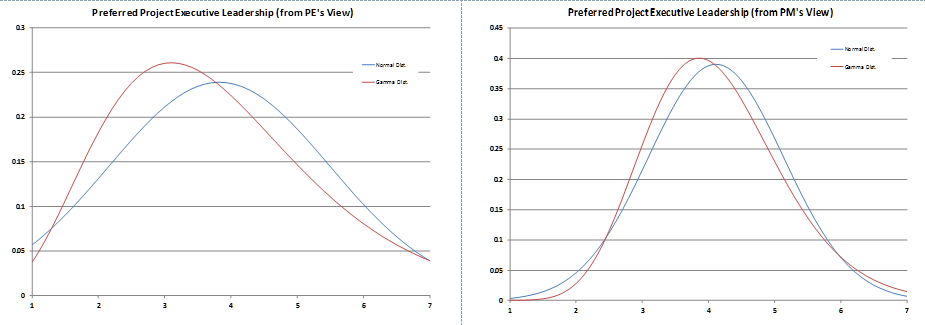

6.2.2. Preferred Leadership Style for Project Manager

- The results indicate that construction industry project managers are in positions that require a focus on control, and thus their preferred leadership styles consequently tend towards an autocratic, boss-centered leadership style. The mean scales from the executive and the manager were found 3.71 and 3.47, respectively. However, the variance for this result is lower than that for the project executive position, meaning that the managerial people’s leadership style preference for the project manager position is stronger than that for the project executive. In Figure 3, the Normal and Gamma density curves visually describe the frequency distributions of both preferred leadership style from the executive and manager’s point of view.

| Figure 3. Preferred Leadership Style for Project Managers |

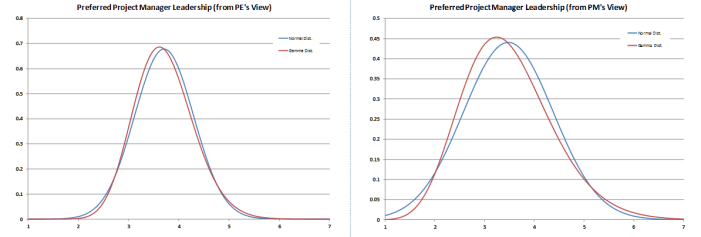

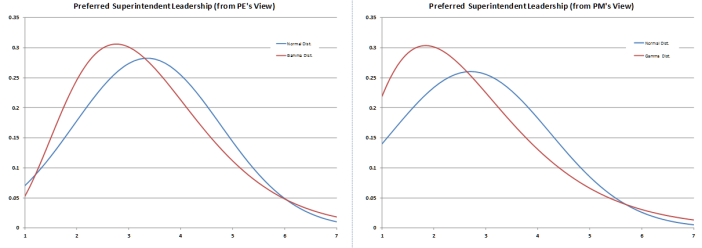

6.2.3. Preferred Leadership Style for Superintendent

- The third position analyzed was the superintendent position. In contrast to the higher two managerial positions, the survey result clearly indicates that the preferred leadership style for this position is more inclined to the autocratic type. The executives tend to like their superintendents to work in a participatory-to-autocratic way, while the managers tend to like them to show a more autocratic leadership. The scale average values were found 3.35 and 2.71 with standard deviation of 1.41 and 1.53 from the executive and manager’s point of view, respectively. The frequency distribution curves are presented in Figure 4.

| Figure 4. Preferred Leadership Style for Superintendents |

6.3. Statistical Analysis

- The average scale values and the distribution curves presented in the previous section indicate that both project executive and manager seem to have the same opinion in terms of their preferred leadership style for all the three managerial positions. To ensure and verify the claim statistically, the scale values collected were subjected to normality tests (i.e., comparison of two means – two sample t-test). The statistical hypothesis setting is as follow:H0: Both project executives and managers have the same opinion on the preferred leadership style for each of three positions.H1: Project executives and managers do not have the same opinion on the preferred leadership style for each of three positions.The t-test was conducted with a 95% confidence level. The test results are shown in Table 5.

|

7. Future Study

- This study is aimed specifically at recognizing the issue of appropriate leadership styles for diverse managerial positions from the perspective of construction professionals currently working at senior project manager and executive levels. The survey data provides interesting new information that can serve as a benchmark for new types of leadership education based on the type of managerial position, management responsibilities, job function, and interpersonal collaborations with industry stakeholders. Although, the data collection is limited by sample population access and location, this study will establish a new approach to the leadership and decision-making. . Extending this study with a sufficient sample pool, an extended region, and different types of firms, departments, and projects can strengthen the findings of this study on the understanding and direction of leadership programs being developed by academia and industry. The study does provide promise that future studies with broader relationships, such as different types of firms, departments, project types, tasks, and so on, could have a significant impact in further the understanding of appropriate leadership styles at different managerial levels. The study not only provides a vision for employee promotion, but also an insight in how future studies can explore hierarchical leadership styles.

8. Conclusions

- This study initiates the issue of appropriate leadership styles for diverse managerial positions from the perspective of construction professionals currently working at senior project manager and executive levels in the construction industry. Leaders are often only slightly elevated above their peers in terms of legitimate authority, particularly in the construction industry. As a consequence, much of their leadership style relies on influence and persuasion, rather than on authority and commands [24]. The findings of the study support and reflect the different duties, responsibilities, and relationships of the different managerial positions based on personal recognition of senior managerial positions in the construction industry. The traditional view of leaders who set goals, make decisions, and direct troops reflects an individualistic view [25]. Professionals, especially those in managerial positions in the construction industry, often need to deploy different leadership styles that reflect appropriate hierarchical perspectives depending on the management position they hold within the company. Construction is a heavily pre-planned activity that aims to minimize waste, time, and costs. Construction personnel rely on having well-developed interpersonal skills in order to deal with the many different stakeholders and departments they work with. These collaborations must also function at different levels in the hierarchy and meet varying performance requirements. Thus as identified by the data analysis of this study reveals that higher level managerial personnel prefer their superintendents to lean toward more autocratic leadership styles while they prefer project executives and managers to lean toward a more participatory leadership style. The understanding of relationship among desired leadership styles at different managerial levels in the construction industry can achieve high levels of performance in general duties, responsibilities, and relationships of higher managerial positions, including executive, manager, and superintendent. The findings of this study of leadership styles suggest that there are a number of alternative combinations in which a construction professional can consciously conduct him or herself to both accomplish project objectives and succeed professionally as analyzing their own current leadership and decision-making. Additionally, this research suggests how leadership development programs can work to prepare and guide qualified professionals in continued leadership education and professional growth and advancement with the enhancement of societal value.

Appendix

References

| [1] | Y. Jung and T. Mills, "Learning Leadership Skills from Professionals in the Construction Industry," in The 3rd International Conference on Construction Engineering and Management - The 6th International Conference on Construction Project Management Jeju, South Korea, 2009. |

| [2] | R. Tannenbaun and W. H. Schmidt, "How to choose a leadership pattern," Harvard Business Review, vol. 51, pp. 162-180, 1973. |

| [3] | J. E. McCarthy, Construction Project Management. Westchester, IL: Pareto-Building Improvement, 2010. |

| [4] | D. R. Clark. (2004, December 3). Concepts of Leadership. Available: http://nwlink.com/~donclark/leader/leadcon.html. |

| [5] | D. R. Clark. (1997, October 15). Leadership Styles. Available: http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/leader/leadstl.html. |

| [6] | C. O. Skipper and L. C. Bell, "Leadership Development and Succession Planning," Leadership and Management in Engineering, vol. 8, pp. 77-84, 2008. |

| [7] | G. Yukl, Leadership in Organizations, 4th ed. Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 1998. |

| [8] | K. Lewin, R. Lippitt, and R. K. White, "Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally created social climates," Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 10, pp. 271-301, 1939. |

| [9] | D. L. Goetsch and S. B. Davis, Quality Management: Introduction to Total Quality Management for Production, Processing, and Services. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall., 2006. |

| [10] | J. P. Friedman, Dictionary of Business Terms Hauppauge, NY: Barron's Educational Series, Inc, 2000. |

| [11] | R. M. Mendez, J. G. S. V. Munoz, and M. A. M. V. Munoz, "Leadership Styles and Organizational Effectiveness in Small Construction Businesses in Puebla, Mexico," Global Journal of Business Research, vol. 7, pp. 47-56, 2013. |

| [12] | S. Toor and G. Ofori, "Leadership for future construction industry: Agenda for authentic leadership," International Journal of Project Management, vol. 26, pp. 620-630, 2008. |

| [13] | B. George, Authentic leadership: rediscovering the secrets to creating lasting value. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003. |

| [14] | J. M. Burns, Leadership. New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1978. |

| [15] | B. M. Bass, Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations. New York, NY: Free Press, 1985. |

| [16] | H. Giritili and G. T. Oraz, "Leadership styles: some evidence from the Turkish construction industry,". Construction Management and Economics, vol. 22, pp. 253-262, 2004. |

| [17] | A. T. S. Chan and E. H. W. Chan, "Impact of Perceived Leadership Styles on Work Outcomes: Case of Building Professionals," Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, vol. 131, pp. 413-422, 2005. |

| [18] | V. H. Vrooom and P. W. Yetton, Leadership and Decision-Making. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1973. |

| [19] | J. M. Kouzes and B. Z. Posner, Leadership Challenge, 4th ed. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007. |

| [20] | M. F. Dulaimi and D. Langford, "Job Behavior of Construction Project Mangers: Determinants and Assessment," Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, vol. 125, pp. 256-264, 1999. |

| [21] | F. E. Gould and N. E. Joyce, Construction Project Management. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2002. |

| [22] | "Interpretative Guidance for Project Manager Positions," U.S. Office of Personnel Management 2003. |

| [23] | R. Muller and J. R. Turner, "Matching the Project Manager's Leadership Style to Project Type," International Journal of Project Management, vol. 25, pp. 21-32, 2007. |

| [24] | S. Rowlinson, T. K. K. Ho, and Y. Po-Hung, "Leadership style of construction managers in Hong Kong," Construction Management and Economics, vol. 11, pp. 455-465, 1993. |

| [25] | R. L. Daft and D. Marcic, Understanding Management Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Inc., 2001. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML