-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2013; 2(4): 106-112

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20130204.02

An Analysis of Soft Conflict Resolution Approaches in the UK Construction Industry

Andrew Hansen-Addy

Business School, Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration, Achimota, Ghana

Correspondence to: Andrew Hansen-Addy, Business School, Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration, Achimota, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Planning and executing a construction project usually requires inputs and interaction of every functional staff within the project team or organization and other stakeholders such as Clients, Contractors and End Users. These interactions often lead to conflicts over schedules, priorities, technical issues and even over personality. Hence, the study sought to identify the major causes of conflict amongst key stakeholders in construction projects and to analyse the frequency and effectiveness of ‘soft’ conflict resolution approaches. A questionnaire survey was conducted on stakeholders in the UK construction industry to ascertain the nature, frequency and causes of stakeholder conflict. The use of ‘soft’ conflict resolution approaches in construction was also investigated. The study revealed that perceptions on the nature of conflict in the UK construction industry differ to some extent from real experiences. Furthermore, soft conflict resolution approaches are popular amongst construction stakeholders, are effective and should be chosen over hard line approaches. As a result, huge savings can be made when project stakeholders endeavour to apply soft conflict approaches as first choice in conflict situations.

Keywords: Stakeholder, Stakeholder Management, Conflict, Conflict Resolution, Negotiation

Cite this paper: Andrew Hansen-Addy, An Analysis of Soft Conflict Resolution Approaches in the UK Construction Industry, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 2 No. 4, 2013, pp. 106-112. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20130204.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The UK construction industry is considered one of the most advanced in the world. It contributes significantly to economic growth (up to 8% of GDP) and provides employment for over 7% of the UK Labour force[1],[2]. Additionally, the industry employs a wide range of both skilled and unskilled labour in projects all over the UK[3].Given this complexity, it is expected that there would be opposing ideas, objectives and goals in projects. So, managing a construction project is often seen as managing opposing ideas and objectives that require some skill and expertise. The success of a project is often measured by how effective the Project Manager is able to contain possible disagreements and still execute the project as planned by meeting specific targets on quality, budget and time[4],[5].Even though conflict amongst stakeholders in the industry is not new, particular emphasis has been placed on conflict management in recent times such as by the Latham report which portrayed conflict as a damaging phenomenon that needs to be reduced and possibly eliminated from the construction process[6],[7],[4].Moreover, conflict in project management has been addressed over the years with conventional conflict resolution approaches such as litigation and arbitration[8]. Although litigation and arbitration have largely been effective they are very expensive, time consuming and damaging to contractual relationships. These expenses to feuding parties, has led to the development and favouring of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) methods over conventional methods of dispute resolution. ADR methods are in some sense soft conflict resolution methods and are perceived to be less expensive and easier to apply[9], [10],[11].

2. The Research Problem

- Conflict amongst stakeholders in construction can pose a daunting challenge to Project Managers to curtail. Conflicts can be adversely damaging to project delivery resulting in spiralling costs and major delays. In some cases disputes can stall a project altogether and creating an atmosphere of distrust and suspicion amongst project stakeholders[12]. Among the major causes of conflicts is the lack of openness and information to keep the project running, conflict of interests, a lack of experience and cost disputes[12],[13], [14].There is, however, no shortage of suggestions on conflict resolution approaches. Compromise, negotiation integration, smoothing, withdrawal, avoiding, confrontation and dominating are conflict resolution approaches popular among writers on conflict management[7],[15],[12],[8], [14],[16]. On the other hand, research on the extent and effectiveness of these approaches in the UK construction industry is scanty with little comparable data[9],[17],[18], [19]. It is therefore, appropriate that stakeholder conflict and soft conflict resolution approaches in the UK construction industry is the focus of this study. It provides insights into current conflict resolution trends in the construction industry.

3. Aims and Objectives

- It is the purpose of this study to provide a better understanding of the frequency, nature and causes of stakeholder conflict and the soft approaches employed in resolving them. The following further highlights how this can be achieved.§ To analyse the nature of conflicts in the UK construction industry.§ To analyse the frequency and effectiveness of ‘soft’ conflict resolution approaches.§ Propose ways of resolving and reducing conflicts amongst stakeholders.

4. Scope of Research

- This paper is limited to the views of selected construction stakeholders within the UK construction industry. It focuses on Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) methods otherwise referred to as ‘soft’ conflict resolution approaches - their application and effectiveness in construction.

5. Conflict in Construction

- There seems to be conflict everywhere we find people or better still we find opposing thoughts, goals, beliefs, aspirations in every facet of life. So, disagreement in some sense is inevitable. However, when such disagreements prevent people or organizations from achieving set targets even resulting in aggression and hatred then immediate conflict resolution is necessary[20],[21],[22],[23].Furthermore, particular emphasis has been placed on conflict management in construction in recent times owing partially to the detrimental consequences of conflict. Considerable momentum was added by the Latham report which portrayed conflict as a damaging phenomenon that needs to be reduced and possibly eliminated from the construction process[6],[7].

5.1. Conflict and Stakeholders

- Conflict is defined as a clash between hostile or opposing elements or ideas. These elements may not necessarily be aggressive towards each other but in essence are opposed to one another. This opposition could either be destructive or creative, an impasse or a transformation. Between these two extremes are a set of strategies, techniques, and approaches for turning one into another. It is therefore the onus of every individual let alone managers to turn conflicts into transformations that yield beneficial results for all stakeholders[4],[5].At times a difference on how to achieve project objectives can lead to a standoff. Conflict could also result from a basic lack of or unwillingness to understand the views of others[24],[13],[25],[26]. The key to successful conflict management must be a fuller appreciation of the varying aspects of conflict including how and why it arises[27],[28].

5.2. Soft Conflict Resolution Approaches

- A variety of soft conflict resolution or ADR methods have been proposed by many writers because they are less expensive and can effectively diffuse conflicts at an early stage[29]. They include smoothing or compromise which involves the shifting of stand of one party or both through compromise. It involves deemphasizing differences and emphasizing commonalities[4],[12].Avoiding or withdrawing is another soft conflict resolution approach which simply involves ignoring a potential bone of contention. It works in situations where there is enough time to rethink position from both parties. Avoidance strategy is based on the belief that disputes will eventually disappear if ignored and that it is not possible to win against an opponent[7],[4].Integrating, another soft conflict resolution approach, involves a consensus forming to address the feuding problem. This approach has a win-win situation for all. In some cases an arbitrator is appointed by all parties to address the issues.[7],[4],[16].Related to integrating is Negotiation which is generally considered one of the most popular and effective ways of resolving conflicts. In fact the art of effective negotiation is an essential skill needed by any Project Manager. Hence, no Project Manager should attempt to practice his profession without explicit training in negotiation. Negotiation is defined as the process through which two or more parties seek an acceptable rate of exchange for items they own or control. It carries the ideas of mediations, settling differences, bargaining and adjusting differences[30],[14], [31],[32].

6. Research Methodology

- Amongst the variety of data collection methods available, the questionnaire survey is the primary data collection method used in this research. Qualitative and quantitative data was therefore sought through the use of view-point questions in the questionnaire[33].The questionnaires were distributed to Local Planning Authorities, Consultants, Project Managers, Contractors, Clients and other stakeholders in the UK construction industry. This distribution ensured a wide coverage of the industry.Leading construction firms in the UK with turnovers of over 100 million were specially targeted since these firms are large and would most likely be engaged in conflict resolution and stakeholder management[34]. In addition Local Authorities played a significant role in this research since these bodies usually consist of construction specialists and are frequently engaged in conflicts with clients and investors over issues relating to planning permissions and obligations. Views of smaller firms were not neglected.There is usually a low response rate to postal questionnaires so the research questionnaires were sent electronically (via email) to the target groups. This method was effective given the ease at which targets can be reached and response sought. In fact, emails can reach wide audiences in a matter of minutes reducing transmission time and encouraging better response[35].Email addresses of stakeholders constituting the target group were drawn from company websites, construction circulars, and journals. Each target received an email containing a brief introduction outlining the purpose of the research and the questionnaire attached in word format. Target groups were also encouraged to forward the questionnaire to other colleagues whom they thought might also provide meaningful information regarding the research, in this way other stakeholders were reached indirectly.An initial pilot study was conducted to determine the feasibility of the survey and the quality of responses received. A total of 3 questionnaires were returned with minor discrepancies. These discrepancies were then corrected for later questionnaires sent out.

|

7. Discussion

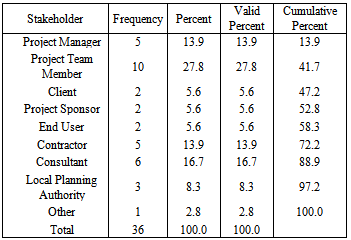

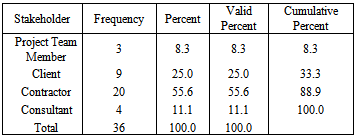

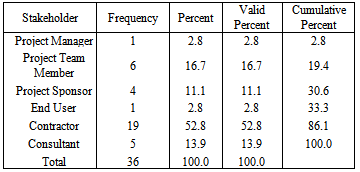

- When we examine data collated from the survey, contractors are top of the list of perceived generators of conflict. They are followed in succession by Clients, Consultants, Local Planning Authority and Project Team Members and others. This means that on the minds of respondents, conflict in construction seems to be mainly fuelled by contractors[14]. On the other hand, data collated from actual experiences slightly differs from the perceptions of the response group. Even though Contractors top the list of both perceived and actual generators of conflict, the correlation for other stakeholders is inconsistent. For instance, Project Managers, Project Team Members and Consultants generate more conflict than perceived; and Clients, Project Sponsors, End Users and Local Planning Authorities generate less conflict than perceived. Tables 2 and 3 reflect this trend.

|

|

|

7.1. Conflict Frequency and the Project Lifecycle

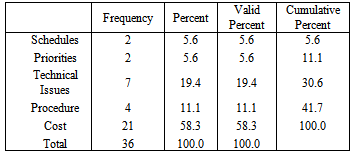

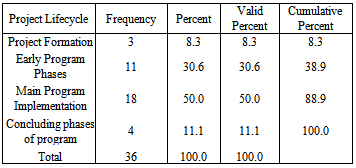

- Conflict levels within a project tend to vary over the lifecycle of the project, partly because as priorities of stakeholders change over time, there may be a shift in commitment levels at different stages of the project. Additionally, since different tasks are performed over time, different stakeholders may be involved at different times [39],[40]. Research conducted by Thamhain and Wilemon on the frequency and magnitude of conflict within the lifecycle of a project indicated that conflicts were highest during the early program phases and lowest towards the end of the project[14]. This data slightly differs from the results received from respondents where conflict is highest during main program implementation rather than early program phases.One possible reason for this shift in conflict intensity during the lifecycle of a project might be the nature of the samples taken. Whereas Thamhain and Wilemon's research was mainly on Project Managers, our analysis involved a wide range of construction stakeholders. In any case, when data from Project Managers is isolated from our overall response, all Project Managers still indicated that conflict was highest during the main program implementation. This response supports the view that Project Managers are mainly concerned with the project and are usually involved with the daily schedules and flow of work during the various phases of the project so it seems reasonable that they would feel conflict to be highest during the main program implementation[14].Additionally, the proportions of types of conflict tend to vary from project formation to completion. Technical conflicts and priorities usually dominate during project formation because the Project Manager would wish to have clearly defined WBS and other schedules to set the project off. Procedure and schedule conflicts dominate during early phases of the program whilst costs, technical and schedule conflicts dominate during the main program implementation. Lastly, conflicts over schedule and personality dominate during the completing phases of a project. So, it is evident that conflicts over schedules permeate much of the project lifecycle so it is therefore not surprising that those concerned most with schedules (mainly Project Managers) believe that conflict is highest during early and main program implementation[14],[41]. Table 5 reflects this trend.

|

7.2. Conflict Resolution Approaches

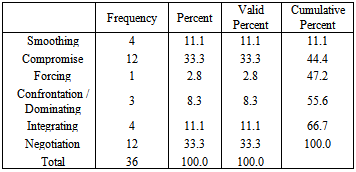

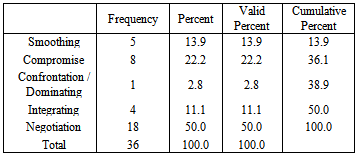

- The success of a conflict resolution approach largely depends on the timing and context of its application. When the data received from respondents is examined, all respondents had at least attempted more than one conflict resolution style and therefore could determine which approach was most effective. This distribution is similar to approaches propagated by many Dispute Avoidance and Resolution Techniques (DART) which are basically a combination of a variety of dispute resolution approaches [19].However, there seems to be a high recommendation for ‘soft’ conflict resolution approaches such as compromise and negotiating skills in dispute resolution. In fact, compromise as discussed earlier is seen as a very effective conflict resolution style because it deemphasizes differences whilst emphasizing commonalities between conflicting parties, a team spirit is brought to the fore. That may explain why a large proportion of respondents had attempted this conflict resolution approach and recommended it since persistent disputes could distract stakeholders from the main objectives of the project[4],[12].The same can be said of negotiating skills which is considered one of the most popular and effective ways of resolving conflict. Whereas 33% of respondents had attempted negotiation, 50% actually recommended it. This confirms the perception amongst many researchers that negotiation is an effective and dynamic tool in dispute resolution. One of such studies was by conducted by John H. Ock and Seung H. Han on a dispute between two departments within an organization. They concluded that when conflicts are handled in a rigid manner, such as using hard-line conflict resolution approaches (like confrontation and forcing) the conflict more often than not escalates to high levels. On the other hand, conflict levels subside when parties decide to use less aggressive tactics like compromise and smoothing to resolve their differences. In any case, it is always reasonable to approach conflict less aggressively [42],[28].None of respondents to the survey noted that they had attempted or would recommend avoiding or withdrawal as a conflict resolution style making this approach very unpopular.This trend can be explained by the profile of respondents to the survey who were mainly professionals and clients within the construction industry. Given that a measure of professional ego is exhibited by the various construction professions against each other, it seems unlikely that a party would choose to withdraw or avoid another party when conflict ensues. Similarly, clients and project sponsors would have invested large amounts of cash into a project and would not simply let go of disagreements even if they do not border on financial matters. It is therefore reasonable to believe that avoidance and withdrawal conflict resolution approaches are mainly employed by less prominent stakeholders or secondary Stakeholders since these have little and in some cases no influence at all on the outcome of the project[42]. Tables 6 and 7 highlight this inclination.

|

|

8. Limitations and Future Research

- A major limitation is the use of questionnaires as sole means of primary data collection for this research. Questionnaire surveys are limited in the sense that there is no interaction between the investigator and respondents, so respondents may interpret some questions differently from what we intended. This study does not discuss hard-line conflict resolution approaches such as litigation and arbitration employed by UK construction stakeholders into detail. Additionally, views of respondents expressed herein are biased towards primary stakeholders such as Project Managers, Quantity Surveyors, Engineers, Consultants, Engineers and Contractors since these form the bulk of the number of respondents.Based on the limitations of this study, the following are recommended for future research: The results of the survey are tested by the use of interviews and case studies or a wider target group to eliminate any possible bias. It is also recommended that gains that can be made when soft conflict resolution approaches are used in place of litigation and arbitration is investigated.

9. Conclusions

- Perceptions in the construction industry as seen in the discussions vary among different stakeholders and professions. For instance, Clients and Project Managers most often would point fingers at Contractors for fuelling project related conflict whereas Contractors would likely blame Clients and Consultants for disagreements. However, it can be concluded from this study that perceptions differ from actual experiences and that some stakeholders may provide a different impression of what actually pertains on the ground. It seems therefore that actual experiences should supersede perceptions in determining the nature of conflict in the UK construction industry.It is reasonable, therefore, to believe from this research that disputes with contractors seem unavoidable and persistent in all construction projects, mainly because contractors play a crucial role in the final delivery of a project and that contractors often abuse this advantage. This is not say that all conflicts in construction are fuelled by contractors, but that contractors need to be looked at more carefully.On the other hand conflicts over financial issues dominate literature and again bear heavily on the minds of respondents for this study. So given that the construction industry invests heavily in the UK economy and that there is a need to minimise waste and improve on productivity, conflicts over legitimate cost reduction would not cease[1]. Conflicts over technical issues, schedules, and priorities also characterize many projects in the UK construction industry.Conflict levels in the lifecycle of projects peak during the main program implementation according to analysis of the primary data. As discussed earlier this discovery slightly differs from similar surveys[14] However, it is undeniably evident from this study and literature that conflict levels are not static, are less at the outset of the project, peak and generally decline at the concluding phases of the project as a result of fluctuations in intensity of conflicts over schedules, priorities, technical issues and personality.It is reasonable also to believe ‘soft’ conflict resolution approaches are quite popular among UK construction stakeholders over litigation and arbitration. This trend has a tremendous effect on attitudes and perceptions of people in construction. Large savings are made when lawsuits are avoided. Additionally, relationships are not strained to breaking points, as in many litigation cases that drag on over months and even years, but are patched early if ‘soft’ conflict resolution approaches are used.Furthermore, negotiation and compromise are among the most effective and recommended conflict resolution approaches identified in this study. Whereas, forcing and dominating were least attempted and effective. This is not to say that hard-line approaches do not work, but then on the balance of success in effectively resolving construction related disputes, ‘soft’ conflict resolution approaches have an upper hand. This satisfies one of the main objectives of this study, which was to determine the effectiveness and usage of soft conflict resolution approaches in the UK construction industry.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The material for this paper was extracted from an MSc dissertation in project management on ‘An Analysis of Stakeholder Conflict and Soft Conflict Resolution Approaches in the UK Construction Industry’ on which the author carried out further analysis.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML