-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Brain and Cognitive Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1840 e-ISSN: 2163-1867

2020; 9(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.ijbcs.20200901.01

Relationship Between Self-Control and Behaviour Modification Among Secondary School Students in Kenya

Tom K. O. Onyango1, Peter Jo Aloka2, Pamela A. Raburu2

1Phd Student in Guidance and Counselling, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

2Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

Correspondence to: Peter Jo Aloka, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

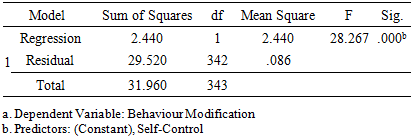

The study investigated the relationship between Vicarious Experience and Delinquent Behaviour Modification among Secondary School Students. Concurrent Triangulation design was used. The target population was made up of 3,740 students, 26 school counsellors and 26 deputy principals from the twenty six (26) secondary schools. The Brief Self-control Scale and Behavior Modification Questionnaire were used to collect quantitative data while interviews and Focus Group Discussions were used to obtain qualitative data. The questionnaires were subjected to the scrutiny of the supervisors to ensure expert content validity and their recommendations used to finally formulate instruments with the ability to obtain the expected relevant data. Reliability results revealed that all the sub-scales reached the required level of internal consistency of reliability, with the Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from a low of 0.701. There was statistically significant positive correlation between self-control and behaviour modification among secondary school students (n=344; r = .276; p<.05). The level of self-control is a significant predictor of behaviour modification among the secondary school students, F (1, 342) =28.267, p=.000 <.05; Adjusted R2=.074. Therefore, it was concluded that there is statistically significant influence of self-control on behaviour modification among the secondary school students. It is recommended that there is need for training of teacher counsellors on enhancement of self control among students.

Keywords: Relationship, Vicarious Experience, Delinquency, Behaviour Modification, Secondary School, Students

Cite this paper: Tom K. O. Onyango, Peter Jo Aloka, Pamela A. Raburu, Relationship Between Self-Control and Behaviour Modification Among Secondary School Students in Kenya, International Journal of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2020, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.ijbcs.20200901.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Behavior modification is the use of basic learning techniques, such as conditioning, biofeedback, assertiveness training, positive or negative reinforcement, hypnosis, or aversion therapy, to change unwanted individual or group behavior. A technique, typically based on functional assessment, used to reinforce adaptive behaviors while diminishing or extinguishing maladaptive behaviors (Kolakowsky-Hayner, 2011). Behavior modification is a type of behavior therapy. B. F. Skinner demonstrated that behavior could be shaped through reinforcement and/or punishment. Skinner noted that a reinforcer is a consequence that increases the likelihood of behavior to recur, while punishment is a consequence that decreases the chance. Positive and negative are used in mathematical terms. Positive indicates that something is added, and negative indicates something is subtracted or taken away. Fantini et al (2019) add that the goal of behaviour modification is to reduce or eliminate undesirable behaviours and teach or increase acceptable behaviours. This is accomplished through the use of behavioural techniques and strategies such as systematic desensitization, modelling, reinforcement and aversive conditioning.Self-control can, according to this perspective, be defined as the mechanism that allows for inhibiting or overriding impulses coming from the hot system, allowing precedence of the cold system (Gillebaart and De Ridder, 2017). A related model of self-control is the strength model of self-control (Muraven and Baumeister, 2000). The strength model is one of the most prominent, heavily debated models of self-control, and refers to self-control as an act of self-control by which the self alters its own behavioral patterns so as to prevent or inhibit its dominant response (Muraven and Baumeister, 2000). Self-control has also been defined as the ability to delay immediate gratification of a smaller reward for a larger reward later in time (Kirby and Herrnstein, 1995). self-control refers to the individuals’ ability to overcome or change internal reactions, suppress impulses, and interrupt impulsive behavior response trends, such as changing and adjusting behaviors, thoughts, emotions, and habituation (Li & Zhang, 2011). The deliberative process in which trait self-control confers increased motivation to engage in goal-directed behavior, and greater capacity to actively monitor and resolve cues to impulsive behaviors, and an implicit process in which individuals are biased toward control-related cues and away from cues to impulse related behaviors. Theory on self-control suggests that trait self-control reflects individuals’ capacity for impulse suppression and regulation of action over time (Paschke et al., 2016), and their ability to monitor and attend to cues to engage in goal-directed behaviors, and disregard or manage cues for behaviors that may derail the goal-directed actions (Baldwin, Finley, Garrison, Crowell, & Schmeichel, 2018).According to Gottfredson and Travis (1990), individuals lacking in self-control are insensitive to others and are risk-taking, and more likely to experience problems in social relationships, such as marriage, they are more likely to use drugs and to abuse alcohol, and they are more likely not to wear a seat belt and to get into automobile accidents. Levesque (2011) reiterate that deficiencies in self-control play an important role in psychopathology, and it tends to be the centerpiece of research conducted by other names, such as delay of gratification, self-regulation, impulsivity, and self-discipline. These terms help highlight the centrality of self-control to healthy development, such as impulsivity and its place in impulse control problems, conduct disorders, and addictions. It is difficult to overestimate the significance of self-control in adolescent development.Literature ReviewPrevious studies have been carried out be between self control and behaviour change. Borushok (2014) in a study examined the relationship between trait self-control, weight loss and various health behaviors commonly associated with successful weight loss. The results showed a relationship between baseline trait self-control and baseline body fat percentage. Cochran, Aleksa and Chamlin (2006) used a sample of college students to reexamine this perspective. They showed that capacity for self-control and desire for self-control has independent effects on academic dishonesty. Tittle and Botchkovar (2005) showed that individuals may be able to perceive some level of control in their behavior through the consequences of their actions. Kuhn (2013) study tested dual-process decision-making models as predictors of between-person and within-person variation in risk-taking behaviour. whereas self-control was linked to lower levels of risk-taking because of lower levels of behavioral intentions. Aart, Terrie, Christian, Steglich, Dijkstra and Wilma (2015) The main findings indicate that personal low self-control and friends’ externalizing behaviors both predict early adolescents’ increasing externalizing behaviors, but they do so independently. Morutwa and Plattner (2014) explored the relationship between self-control and alcohol consumption among students at the University of Botswana. Participants who reported not drinking alcohol at all (55.6%) scored significantly higher in self-control. For those participants who reported drinking alcohol (44.4%), total self-control scores correlated moderately and inversely with alcohol consumption per week. Ferrari, Stevens, and Jason, (2009) study examined the relationships between self-regulation and abstinence maintenance among adults in recovery. In addition, a factor analysis of self-regulation scores resulted in some differentiation between general self-discipline and impulsivity in self-control related to addiction. Tangney, Baumeister, and Angie (2008) reported that Low self-control is a significant risk factor for a broad range of personal and interpersonal problems. The failure of these analyses to yield significant improvements in prediction suggests that self-control is beneficial and adaptive in a linear fashion. Nwagu, Enebechi, and Odo, (2018) study revealed that the students’ level of self-control was a little less than the recommended level. Judistira and Wijaya (2018) showed that only self-control could predict academic achievement. Mohammad Sadegh Shirinkam et al (2016) study was conducted on 395 female and male university students of SardarJangal University, Rasht, Iran. In addition, coefficient β is negative which indicate an inverse relation between self-control and internet addiction; increase in self-control would decrease internet addiction (p<.002). Williams and French (2011) estimated the association between specific intervention techniques used in physical activity interventions and change obtained in both self-efficacy and physical activity behaviour. ‘Relapse prevention’ and ‘setting graded tasks’ were associated with significantly lower self-efficacy and physical activity levels. Rawn and Vohs (2011) argue that many of the behaviors that are typically coded as failures of self-control like smoking cigarettes can be understood as utilizing high levels of self-control. Rawn and Vohs focus on smoking, heavy drinking, binge eating, self-sabotaging intellectual performance, drug use, extreme violence, and consensual unwanted sex. Keinan and Kivetz (2011) show that people with high scores on a “productivity orientation measure” struggle to “take a break from self-evaluation” and are prone to experience “self-control regret,” that is, regret over lost opportunities to enjoy oneself. Guan and He (2018) explored how state self-control influences the intertemporal decisions made by individuals with high and low trait self-control. Throughout the experimental stages, the heart rate variability (HRV) of participants with high trait self-control was significantly higher than that of participants with low trait self-control, indicating that individuals with high trait self-control may have stronger and more stable self-control abilities. Gillebaart and Adriaanse, (2017) demonstrated that trait self-control predicted exercise behavior. Mediation analysis revealed that the association between self-control and exercise was mediated by stronger exercise habits. Job et al., (2010) demonstrated that individuals who believe that self-control is not a fixed or limited capacity, and can be incrementally improved or applied flexibly, have better self-control capacity, and appear not to suffer as greatly from the deleterious effects of availability of self-control resources. Gillebaart and De Ridder (2015) suggest, this may be because adaptive habits allow people with higher trait self-control to go about their lives in a way that allows them to routinely avoid problematic situations, and make the “right” choices in line with their long-term goals. Habits as an underlying process in trait self-control may therefore explain why people high in trait self-control are successful in achieving their long-term goals.De Ridder and Gillebaart (2017) suggest that having high self-control is associated with a better ability to initiate goal pursuit and engage in goal-directed behaviour. In other words, those with high self-control are better able to set goals, act in ways that will help achieve these goals, and experience pleasure from doing so. Furthermore, those high in self-control seem better able to set adaptive routines in pursuit of long-term goals, such that behaviour is automated away from temptations or potential self-control conflicts. Koning, Verdurmen, Engels, van den Eijnden, and Vollebergh (2012) investigated whether scores on the Self-Control Scale moderated the effect of adolescent skills training, parent skills training or a combined intervention on the onset of weekly drinking and heavy weekly drinking in a sample of Dutch adolescents. The combined intervention was effective in delaying the onset of weekly drinking in adolescents with low selfcontrol. No such effect was found for the onset of heavy weekly drinking. No effects were found for the other intervention conditions. Daly, Delaney, and Baumeister (2015) found that a decline in heavy smoking following a national workplace smoking ban and a 20% tax increase on cigarettes in the Netherlands was only evident amongst those with low trait self-control, and not those with high self-control. Rising and Bol (2017) examined whether self-control moderated the impact of menus adapted to show calorie information on the selection of a range of salads and beverages. Whilst no moderation by self-control was found, conditional effects indicated that calorie information influenced selection of lower calorie salads only amongst participants with low impulsivity and high restraint (two subscales of the Self-Control Scale). Junger and Van Kampen (2010) found that people with high self-control report engaging in exercise more often than those with less self-control. For many people, dispositional self-control seems to also be an important tool for regulating eating. Individuals scoring high in dispositional self-control are more likely than those lower in self-control to report healthy dietary practices such as eating a regular breakfast and avoiding unhealthy sweets. Wills et al. (2007) conceptually replicated the effect of self-control on diet and exercise behavior in a large, multiethnic sample of high school students. The only evidence we could find suggesting that self-control related specifically to changes in weight involved weight gain rather than loss. From the reviewed study, very scanty information was available on behavior modification among students in secondary schools. In addition, most reviewed studies have been either quantitative or qualitative in nature, but the present study adopted a mixed methods design. In Rongo Sub-county of Kenya, there are several students who are currently undergoing counselling with the aim of addressing delinquent behavior issues. The delinquent behavior issues range from stealing, aggression, fighting, sneaking out of school, substance abuse, lateness in attending lessons, lesson missing, use of abusive language on others, disrespect to teachers and many others. Thus, the study investigated the relationship between Vicarious Experience and Delinquent Behaviour Modification among Secondary School Students.

2. Research Methodology

- Research Design and participantsThe Concurrent Triangulation design was used. Triangulation refers to a combination of methodologies in a study of the same phenomenon (Rothbauer, 2008). In this design therefore, both quantitative and qualitative data were collected and analyzed at the same time of the research study. The researcher therefore gave equal priority to both components (Murdin, 2009). The target population was made up of 3,740 Rongo Sub-County students, their school counsellors twenty six (26) and twenty six (26) deputy principals from the twenty six (26) secondary schools. Research toolsThe Brief Self-control Scale was used to collect data on self-control among students. The response scales was in Likert format such as Strongly Agree (SA), Agree (A), Neutral (N), Disagree (D) and Strongly Disagree (SD). Behavior Modification Questionnaire for Students Was also used to obtain data on behavior change among students. These were rated using the scale of Strongly Disagree (SD), Disagree (D), Unsure (U), Agree (A) and Strongly Agree (SA). The questionnaires were subjected to the scrutiny of the supervisors to ensure expert content validity and their recommendations used to finally formulate instruments with the ability to obtain the expected relevant data. Reliability results revealed that all the sub-scales reached the required level of internal consistency of reliability, with the Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.701 (self-control questionnaire).Data collection proceduresThe Data was collected after obtaining permission from National Commission for Science Technology and Innovation - NACOSTI through the University’s School of Post Graduate letter of introduction. Thereafter, the researcher obtained permission from the principals of the sampled secondary schools. The questionnaires were issued to the students on prearranged days as the best way to ensure optimum cooperation, participation and high students’ response. The questionnaires took an average of 45 minutes to complete while Interviews and Focus Group Discussions took 30-45 minutes to undertake.Data analysisThe methods of inquiry employed were interviews and questionnaires. The data was analyzed using descriptive statistics and Bivariate analyses using simple cross-tabulations. Quantitative data was analyzed using frequency tables, descriptive statistics (frequency distribution and descriptive statistics such as percentages, means, and standard deviations). This data was got mainly from the teacher counsellors’ and deputy principals’ interview schedule. The Pearson correlation while qualitative data analysis was carried out through thematic frame work. In exploring the views of the students on their self-control, a Likert scaled itemed questionnaire was used. The items of the questionnaire were indicators of self-control among secondary school students. The responses were scored using a five point scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The scores were averaged to measure the respondents’ attitude on their level of self-control. The student behaviour modification was interpreted from the summation of their characteristics as exhibited in indicators of behaviour after going through counseling services. The sampled students were provided with questionnaires with indicators of behaviour modification and were asked to rate their behaviour in regards to these characteristic.

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire Return Rate

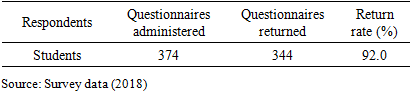

- Information on return rate of questionnaires was obtained. Table 1, which shows the summary of return rate of questionnaires from the student respondents, reveals that the questionnaires were adequate for the study.

|

3.2. Results on Relationship between Self-Control and Behaviour Modification among Secondary School Students

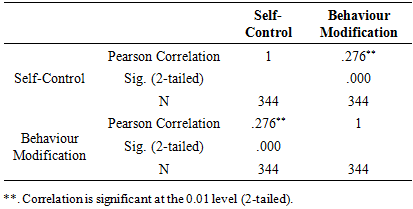

- The hypoothesis was stated as follows:H01: There is no statistically significant relationship between self-control and behaviour modification among secondary school students in Rongo Sub-County.In order to test the null hypothesis, a Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficient was computed with scores on students’ self-control as independent variable and behaviour modification as dependent variable. The scores of independent variable (students’ self-control) was computed from frequencies of responses by computing mean responses per respondents. Mean response across a set of questions of Likert scale responses in each item was computed to create an approximately continuous variable, within an open interval of 1 to5, that is suitable for the use parametric methods, as explained by Johnson & Creech (1983) and Sullivan & Artino (2013). This was done after reversing the negatively worded statements, where high scale ratings implied high perceived students’ self-control. Equally, behaviour modification was computed in a similar manner from the student responses on its indicators. The significant level (p-value) was set at .05, where, if the p-value is less than 0.05, the null hypothesis would be rejected and conclusion reached that a significant difference exist. However, if the p-value is greater than 0.05, it would be concluded that a significant difference does not exists. Table 2 shows the SPSS output correlation analysis results.

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

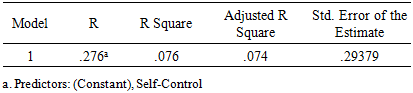

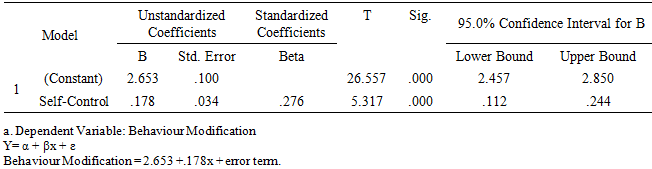

- The study reported that there was statistically significant positive correlation between self-control and behaviour modification among secondary school students (n=344; r = .276; p<.05). The model summary reveals that students’ level of self-control accounted for 7.4% (Adjusted R2 =.74) of the variation in their behaviour modification. This finding indicates that variation in the students’ self-control explains about 7% of the variability in behaviour modification among the secondary school students. From the model it is evident that the slope coefficient for student self-control was 0.178 (B=.178), implying that student behaviour modification improves by this units for each one unit improvement in the level of self-control among the secondary school students. Borushok (2014) reported a relationship between baseline trait self-control and baseline body fat percentage. Cochran, Aleksa and Chamlin (2006) showed that capacity for self-control and desire for self-control has independent effects on academic dishonesty. However, Tittle and Botchkovar (2005) showed that individuals may be able to perceive some level of control in their behavior through the consequences of their actions. Kuhn (2013) reported that self-control was linked to lower levels of risk-taking because of lower levels of behavioral intentions. Aart, Terrie, Christian, Steglich, Dijkstra and Wilma (2015) indicate that personal low self-control and friends’ externalizing behaviors both predict early adolescents’ increasing externalizing behaviors, but they do so independently. Morutwa and Plattner (2014) reported that the participants who reported not drinking alcohol at all (55.6%) scored significantly higher in self-control. For those participants who reported drinking alcohol (44.4%), total self-control scores correlated moderately and inversely with alcohol consumption per week. Junger and Van Kampen (2010) have recently found that people with high self-control report engaging in exercise more often than those with less self-control. For many people, dispositional self-control seems to also be an important tool for regulating eating. Individuals scoring high in dispositional self-control are more likely than those lower in self-control to report healthy dietary practices such as eating a regular breakfast and avoiding unhealthy sweets.From qualitative data, the main themes emerged through thematic narratives by participants who were involved in the interviews and focus group discussions. The themes on the relationship between self-control and behavior modification of secondary school students included thinking before acting, moderating reactions (check overreactions, element of restraint), seeking for advice to solve issues, behaving better than before counselling, and making own decisions. Rawn and Vohs (2011) argue that many of the behaviors that are typically coded as failures of self-control—like smoking cigarettes can be understood as utilizing high levels of self-control. Keinan and Kivetz (2011) show that people with high scores on a “productivity orientation measure” struggle to “take a break from self-evaluation” and are prone to experience “self-control regret,” that is, regret over lost opportunities to enjoy oneself. Gillebaart and Adriaanse, (2017) revealed that the association between self-control and exercise was mediated by stronger exercise habits. Job et al., (2010) add that researchers have demonstrated that individuals who believe that self-control is not a fixed or limited capacity, and can be incrementally improved or applied flexibly, have better self-control capacity, and appear not to suffer as greatly from the deleterious effects of availability of self-control resources. De Ridder and Gillebaart (2017) suggest that having high self-control is associated with a better ability to initiate goal pursuit and engage in goal-directed behaviour. In other words, those with high self-control are better able to set goals, act in ways that will help achieve these goals, and experience pleasure from doing so. Furthermore, those high in self-control seem better able to set adaptive routines in pursuit of long-term goals, such that behaviour is automated away from temptations or potential self-control conflicts.

5. Conclusions & Recommendations

- From the study findings, it is concluded that there is statistically significant positive relationship between self-control and behaviour modification among secondary school students in Rongo Sub-County, with high level self-control and associated to better behaviour modification among secondary school students. the level of self-control is a significant predictor of behaviour modification among the secondary school students. there is statistically significant influence of self-control on behaviour modification among the secondary school students. This suggests that secondary school student with high level self-control is likely to exhibit high behaviour modification. The themes on the relationship between self-control and behavior modification of secondary school students included thinking before acting, moderating reactions seeking for advice to solve issues, behaving better than before counselling, and making own decisions. From the study findings, it is recommended that there is need for training of teacher counsellors on enhancement of self control among students.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML