-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Brain and Cognitive Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1840 e-ISSN: 2163-1867

2019; 8(1): 1-5

doi:10.5923/j.ijbcs.20190801.01

Standardization and Validation of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in the Moroccan Population

Abdelhak Azdad1, Maria Benabdljlil2, Khadija Al Zemmouri3, Mostafa El Alaoui Faris4

1University Mohammed V. Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Rabat, Morocco (Doctoral Student in Clinical Neuropsychology)

2Neurology A and Neuropsychology Department, Rabat Specialty Hospital, Souissi quarter -Rabat, Morocco (Professor of Neurology and Neuropsychology)

3Day Care Center for Alzheimer Patients. Nahda 2 quarter -Rabat, Morocco (Professor of Neurology)

4Day Care Center for Alzheimer Patients. Nahda 2 quarter -Rabat, Morocco (Professor of Neurology and Neuropsychology and Director of the Center)

Correspondence to: Abdelhak Azdad, University Mohammed V. Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Rabat, Morocco (Doctoral Student in Clinical Neuropsychology).

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a cognitive screening test designed to assist health professionals in the detection of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease (AD). Objectives: The aim of our work was to perform the adaptation and standardization of the MoCA in the Moroccan population, taking into account its different demographic characteristics, i.e., age, gender and education level. The second aim was to evaluate the predictive validity of the test in Moroccan patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Patients and Methods / Material and Methods: First we administered the MoCA-ma to 120 normal participants (60 men and 60 women). All the participants can read and speak Arabic, they had no neurological, neuropsychological, psychiatric or toxic history and they had a preserved cognitive functioning. Subjects were categorized according to age and educational level. Secondly, we administered the MoCA-ma and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE-ma) to 40 healthy controls and 40 subjects fulfilling diagnostic criteria for AD. All the patients diagnosed as having AD underwent complete neurologic and somatic clinical examination, usual laboratory testing and MRI. Results: The MoCA-ma norms were established considering significant influential factors. Indeed, the normative data in this version have shown that performance of normal participants depend mainly on age and level of education while gender had no significant influence. The results of validation showed that the MoCA-ma was sensitive enough to detect cognitive impairment in subjects with AD. Conclusion: The standardization and validation of the Arabic version of the MoCA-ma provides to physicians an useful brief cognitive screening tool for the detection of AD in the Arabic countries.

Keywords: MoCA-ma, MMSE-ma, Alzheimer's disease, Adaptation, Standardization, Validation, Moroccan population

Cite this paper: Abdelhak Azdad, Maria Benabdljlil, Khadija Al Zemmouri, Mostafa El Alaoui Faris, Standardization and Validation of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in the Moroccan Population, International Journal of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-5. doi: 10.5923/j.ijbcs.20190801.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Normal aging, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia represent a continuum of cognitive states in the elderly individuals. Identification of the prodromal phase of Alzheimer's disease (AD) is very important, because it can lead to early therapeutic intervention (medication and cognitive treatment).However, commonly used instruments, such as the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [1], are not sensitive enough to detect an eventual early cognitive impairment. In this perspective the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), which was published in 2005 by Nasreddine ZS [2],was specially developed and designed to assist health professionals in the detection of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. It (administered approximately in 10 to 15 minutes) allows a comprehensive assessment of major cognitive domains: short-term memory, visuospatial abilities, executive functions, attention, concentration, working memory, language and orientation in time and space. The MoCA has been adapted to different languages and validated in many countries [3-14].In our context, the first aim of the present work was to perform the adaptation and standardization of the MoCA in the Moroccan population, taking into account its different demographic characteristics, i.e., age, gender and education level.The second aim was to evaluate the predictive validity of the test in Moroccan patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Translation of MoCA in Moroccan Dialect

- The original version of MoCA was initially translated in Moroccan dialect. Its final version (MoCA-ma) used in this study contained some cultural and linguistic changes for developing better cultural and language compatibility: § Item 1 (Visuospatial/Executive Functions): Arabic alphabets were used for alternating Trail-making Test Part B and the number of steps required for completion of task was retained.§ Item 2 (Memory): The five English words are replaced with five arabic words (وجه -قطن - ياسمين - مسجد -أحمر) to reflect local familiarity.§ Item 3 (Attention): for auditory vigilance part Arabic alphabet were recruited with identical response order and character number to original English test.§ Item 4 (Language-sentence repetition): The two sentences of the original version were replaced by two sentences in Arabic dialect to reflect local familiarity.§ Item 5 (Language-verbal fluency): We chose the letter (ب) for the subtest of the Phonemic letter fluency.§ Item 6 (Abstraction): The four English words are replaced with four Arabic words (ساعة - مسطرة - دراجة - قطار) to reflect local familiarity.Furthermore, one point was added to the total MoCA-ma score if the subject had 12 or less years of formal education, as suggested in Nasreddin’s original study [2].

2.2. Pilot Study

- The Moroccan version of MoCA (MoCA-ma) was initially tested on 25 healthy persons with intact cognition and no underlying disease. Preliminary results showed good internal consistency. No difficulties were encountered during the testing and subjects gave favourable feed-back when questioned regarding comprehension and ease of the questionnaire.

2.3. Study Population

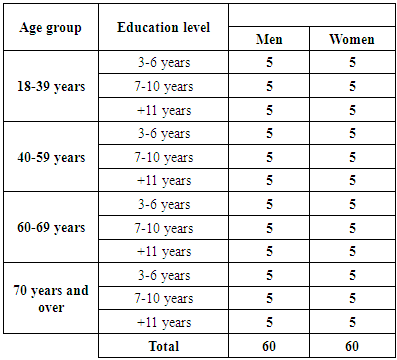

- First, we administered the MoCA-ma to 120 normal participants (60 men and 60 women). All the participants can read and speak Arabic, they had no neurological, neuropsychological, psychiatric or toxic history and they had a preserved cognitive functioning. Subjects, described in the table below (Table 1) were categorized according to age group, gender and educational level.

|

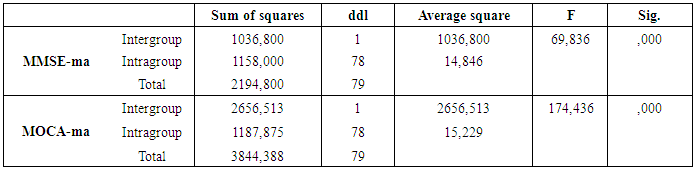

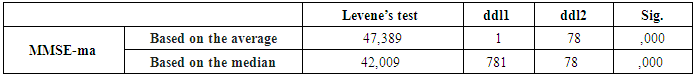

2.4. Statistical Analysis

- The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 22.0 was used for the data analyses. Normative data of MoCA-ma test are provided corrected for gender, age group and education level.MoCA-ma and MMSE-ma scores for each of the two groups (AD and NC) were compared by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) (with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple testing). Differences between groups regarding demographic variables (age and education level) were investigated using Levene’s test and U de Mann-Whitney value, depending on the measurement of variables.Sensitivities and specificities were measured at threshold scores. P values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant throughout the analysis.

3. Results

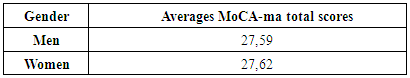

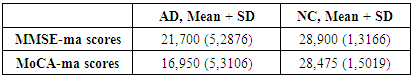

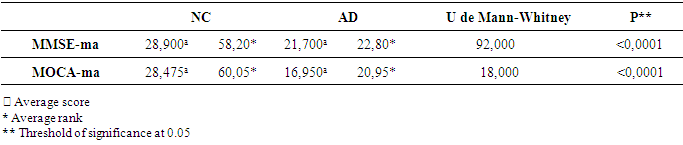

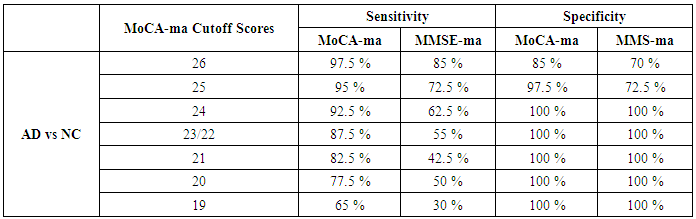

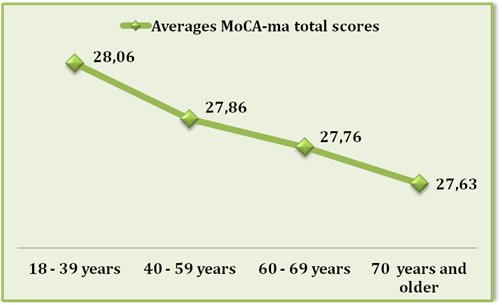

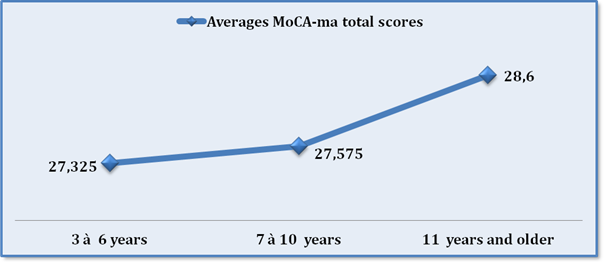

- The MoCA-ma norms were established considering significant influential factors. Indeed, the normative data in this version have shown that performance of normal participants depend mainly on age (Figure 1) and education level (Figure 2) while gender (Table 2) had no significant influence.

| Figure 1. The results of averages MoCA-ma total scores by age group |

| Figure 2. The results of averages MoCA-ma total scores by education level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- As compared with a literature review, our results presented in the present study corroborate the results of Nasreddine ZS [2, 3], Rosdinom Razali [4], Memoria CM [5], Michal Lifshitz [6], Jihui Lu [7], Karunaratne S [8], Freitas S [9], Selekler K [12], Rahman TT [13] and Lee JY [14].Indeed, the higher is the level of education more the performance of the general intellectual efficiency, evaluated by MoCA-ma, is better; on the contrary, the performance decreases with age. However, sex had no relevant influence on the performance of our participants; the same conclusion is found in the literature.In summary, for the standardization of MoCA-ma, we can conclude that the performance of normal participants depend mainly on age and level of education.A cutoff of 26 in MoCA-ma (scores of 25 or below indicate impairment) yielded the best balance between sensitivity and specificity for the AD groups. In addition, the specificity of the MoCA-ma to exclude elderly normal controls was excellent (85%), although slightly lower than the MMSE-ma (70%). More important, the MoCA-ma’s sensitivity in detecting AD was excellent (97.5%), and it was considerably more sensitive than was the MMSE-ma (85%) (table 7).On the other hand, this study showed a significant positive correlation between MoCA-ma and MMSE-ma scores with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.890 (p b 0.001). This positive linear relationship between MOCA-ma and MMSE-ma scores was comparable to those reported by the original author of MoCA, which obtained high correlation between both tools with correlation coefficient of 0.87 (p b 0.001) [2].There are several features in MoCA-ma’s design that likely explain its superior sensitivity for detecting AD. The MoCA-ma’s memory testing involves more words, fewer learning trials, and a longer delay before recall than the MMSE-ma. Executive functions, higher-level language abilities, and complex visuo-spatial processing can also be mildly impaired in AD participants and are assessed by the MoCA-ma with more numerous and demanding tasks than the MMSE-ma.Some limitations of this study should be mentioned. First, we could not apply the MoCA-ma to illiterate subjects because some of the MoCA-ma sub-tests (ie, the trail-making B task, the clock drawing task, and the sustained attention task) require literacy. Second, the number of participants in the validation study was relatively small.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The standardization and validation of the Arabic version of the MoCA-ma provide to physicians an useful brief cognitive screening tool for the detection of AD in the Arabic countries. It has a high sensitivity rate and is valid as a single screening instrument for this condition.In the future, it is recommended that the MoCA-ma be tested for its reliability and validity in a population already prediagnosed as having Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) using more strict diagnostic criteria and neuropsychological tests. A cut-off score for MoCA-ma should be determined for it to have high sensitivity and specificity as a screening instrument for MCI.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors are grateful to all subjects who participated in this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML