-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Brain and Cognitive Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1840 e-ISSN: 2163-1867

2016; 5(1): 7-14

doi:10.5923/j.ijbcs.20160501.02

Adaptation and Standardization of the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test to the Moroccan Population

Abdelhak Azdad 1, Fatima Boutbibe 2, Maria Benabdljlil 2, Mostafa El Alaoui Faris 2

1University Mohammed V. Faculty of Medecine and Pharmacy-Rabat, Morocco

2Department of Neurology A and Neuropsychology, Rabat Specialty Hospital, Souissi quarter-Rabat, Morocco

Correspondence to: Abdelhak Azdad , University Mohammed V. Faculty of Medecine and Pharmacy-Rabat, Morocco.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The significant and progressive impairment of episodic memory supported by reliable neuropsychological testing is an essential criterion for the diagnosis of probable Alzheimer's disease. Indeed, the Free and Cued Selective Reminding test keeps a vital role to diagnose the nature of memory impairment and it currently remains the most relevant clinical practice in neuropsychological tests assessing of episodic memory because it can control the process of encoding and retrieval based on the principle of encoding specificity that Tulving and Thomson have introduced. The goal of our work is to describe the adaptation and standardization of the Free and Cued Selective Reminding test to the Moroccan population, taking into account its different sociolinguistic variables. The sample consisted of 170 normal participants, aged between 18 and 83 years. Normative data from this study showed that memory performance of subjects depend on the age and level of education while sex has no significant influence on them.

Keywords: Episodic memory, Alzheimer's disease, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, Adaptation, Standardization, Moroccan population

Cite this paper: Abdelhak Azdad , Fatima Boutbibe , Maria Benabdljlil , Mostafa El Alaoui Faris , Adaptation and Standardization of the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test to the Moroccan Population, International Journal of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2016, pp. 7-14. doi: 10.5923/j.ijbcs.20160501.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Episodic memory is a subsystem of the long-term memory, which enables us to remember and be aware of the events that have been personally experienced and acquired in a particular spatial and temporal context. This is the most affected cognitive ability in the context of neurodegenerative diseases, among which the Alzheimer's disease (AD) comes first on the list [1]. The International Task Force on Alzheimer's disease [2] proposed new diagnostic criterions for probable AD. The main criterion is the presence of significant and progressive impairment of episodic memory confirmed by objective tests. The neuropsychological assessment tests of episodic memory retain a key role in diagnosing the nature of memory impairment. However, most of these conventional tests do not control the processes actually implemented by the subject during the different stages of mnemonic operation. In particular, they allow with difficulty to identify the specific characteristics of a patient's memory deficit in relation to another (for example, memory problems associated with normal aging, an anxiety-depressive syndrome, a cognitive disorder light or incipient dementia). In this perspective, Grober and Buschke [3, 4] developed a test of verbal memory, which is currently among the most relevant and used in the exploration of episodic memory and in particularly the exploration of three phases of mnemonic processing (encoding, storage and retrieval) [5-7]. It allows controlling the conditions of encoding and retrieval using semantic clues, and therefore it identifies a hippocampal amnesic syndrome type that manifested by significant deficit scores of free recall and total recall, reflecting therefore inefficient cueing [8].This paradigm of selective memory was originally proposed by Buschke [9, 10] in a test of selective recall. It is based on a measurement of a guided learning, once the selective recall is performed the items are not mentioned. Later, Buschke [11] added a parameter that helps to recall. This version is known as the free and cued recall test with selective recall, in which the encoding process is controlled by requiring about the encoding of items (drawings) in response to semantic clues. These clues are then used to facilitate the recovery of not mentioned items in free recall. Recovery operations reflect the principle of encoding specificity that Tulving and Thomson have introduced [5]. According to these authors, the presentation of evidence during the encoding and retrieval improves memory performance. In to other words, the effectiveness of retrieval cues depends on the conditions under which the information has been encoded.In 1987, Grober and Buschke [3] presented another version of this tool: free and cued recall with selective recall - immediate recall. This version follows the same design principles version of Buschke [11] and where the drawings are replaced by the words and adding a splash of immediate cued recall performed after the identification of the different items that are presented on four boards in groups of 4 items. Comparing the two versions, Buschke [12] indicates a preference for the use of written words (as opposed to the use of the drawings) to avoid misperceptions and also to ensure that all subjects use the same track encoding of items, and therefore avoid double perceptual-verbal encoding.Normative data for the English version of the test is a part of the project team "Mayo's Older Americans Normative Studies" (Moans: [13]). The sample consisted of 734 subjects, aged between 56 and 98 years.The Spanish version was developed under the Spanish multicenter studies (project NEURONORMA: [14]). The reference sample consists of 340 participants, aged between 50 and 94 years. In France, the first adaptation of the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT) was conducted by Van der Linden & al [15]. Their reference population is composed of 483 people, aged between 16 and 100 years; so the second standardization, entitled "Study of 3 Cities", was conducted by Amieva and his colleagues in 2007 [16] on a sample of 1458 subjects older than 65 years. Moreover, the standardization of the Italian version of the FCSRT, based on 12 stimuli instead of 16 stimuli in the English version, was conducted by Frasson et al [17] on a sample of 227 normal adults (98 men and 129 women) with an age average of 66.6 years and an average education level of 11.1 years of schooling.Normative data of all versions, already mentioned, were calculated according to age, education and gender.Because of the usefulness of the FCSRT in the evaluation of episodic memory and the absence, to our knowledge, of an Arabic adaptation of this test, we decided to adapt and standardize it to the Moroccan population taking into account the different criteria of sociolinguistic appropriateness.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

- Specifically, the FCSRT procedure consists of many phases. A first phase encoding control that allows to induce a semantic encoding: 16 words to memorize, belonging to 16 different semantic categories are presented on 4 by 4 sheets. For each sheet, the examiner asks the subject to search and read aloud the word corresponding to the semantic category it provides. When the four items were correctly identified, the plug is removed and the examiner makes an immediate cued recall, that is to say, it provides the same semantic index and the subject must recall the corresponding words. If recovery is incomplete, the examiner repeats the procedure for the only missing items and it goes to the next page when the four items can be recovered. After this encoding; just a short interfering task (counting backwards for 20 to 25 seconds), which ensures that the recovery will be good from the secondary memory. In his waning, the examiner asks the subject to provide in any order all the words he remembers (free recall). After 2 minutes, the non-recalled items are subject to a cued recall (the examiner provides the semantic category of the missing item). If, despite the index, the subject does not give the expected word, the examiner gives the correct answer. This recall, preceded by the interfering task is repeated 3 times. Immediately after the last of three reminders come a recognition test, 48 cards with one word on each, are presented one by one. The task is to identify 16 words learned from the 32 distractors. Finally, 20 minutes later, the event ends with a new free and cued recall.

2.2. Methods

- Because of the absence of studies on the frequency of words in Moroccan Arabic and as a result of the French and Spanish adaptation, we asked 60 students to write all the Arabic words that come to their mind, then we set lists of words classified according to their frequencies and their semantic categories in number of twenty-four. It is from this classification that we have selected 16 words belonging to 16 different semantic categories. These words, used as target items during the learning phase, were chosen so that they are not the most prototypical examples of their class (we removed the most frequent words and the words most rare). Then, 16 other words belonging to the same semantic categories as target items and meeting the same criteria, and 16 words not semantically related to the target items were taken from the lists of words. These 32 words are the same frequency as the target items and were used, for the recognition test, as semantic and neutral distractors. Consequently, we had two lists (the basic list and parallel list), the 16 words of each list are presented on cards in groups of four words. Each card is a standard A4 size sheet arranged "landscape" mode.

2.2.1. Pilot Study

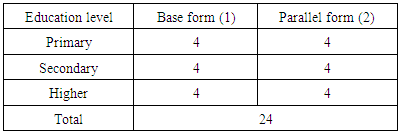

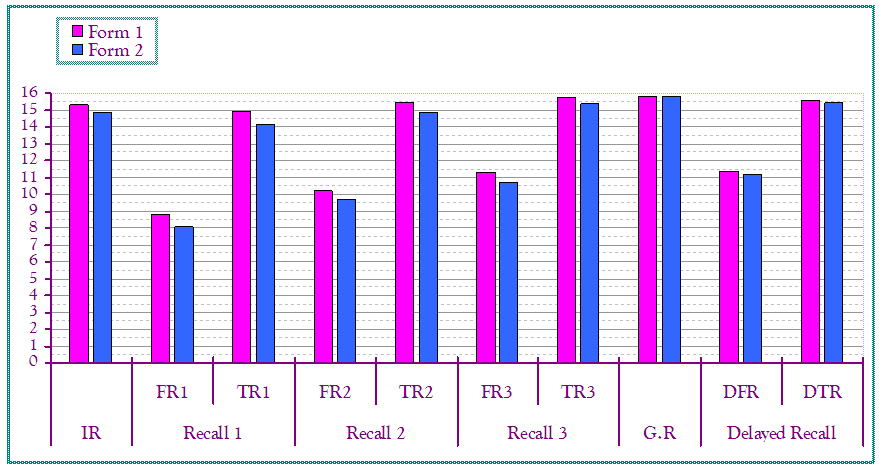

- To determine whether the instructions of the FCSRT in Moroccan Arabic are well understood, and that the words of the two forms and the recognition task is not a problem in the Moroccan population, we conducted a preliminary study of 24 subjects with an age more than 18 years, divided into three categories according to their education levels (primary, secondary and higher). The 24 subjects described above were distributed also in two groups one from the form 1 and the other from the form 2 (Table 1).

|

| Figure 1. The results of the pilot study |

2.2.2. Standardization Study

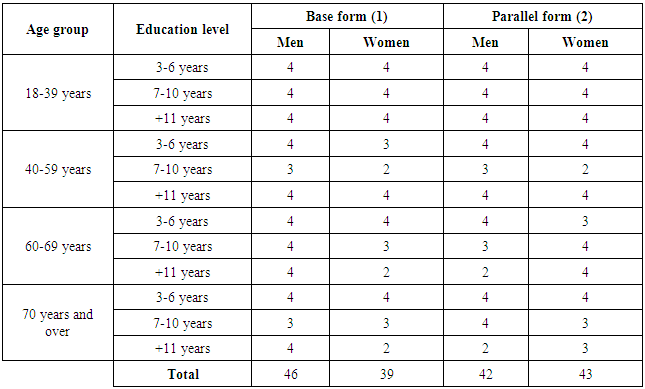

- The sample of our standardization study is composed of 170 normal subjects (88 men and 82 women) described in the table below (Table 2). All the participants can read and speak Arabic, they have no neurological, neuropsychological, psychiatric or toxic history and they have a preserved cognitive functioning, as assessed by the Arabic version of the Mini Mental State Examination [18] that we have passed to all of them.

|

3. Results

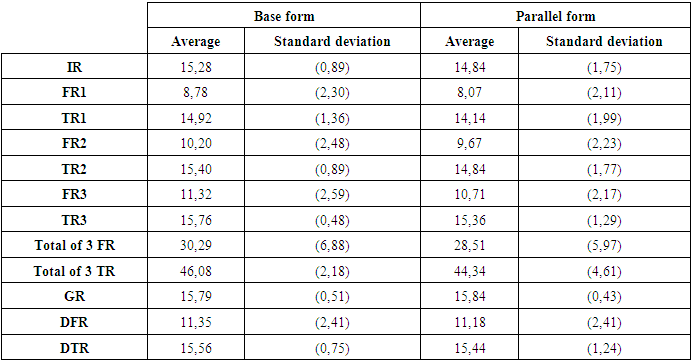

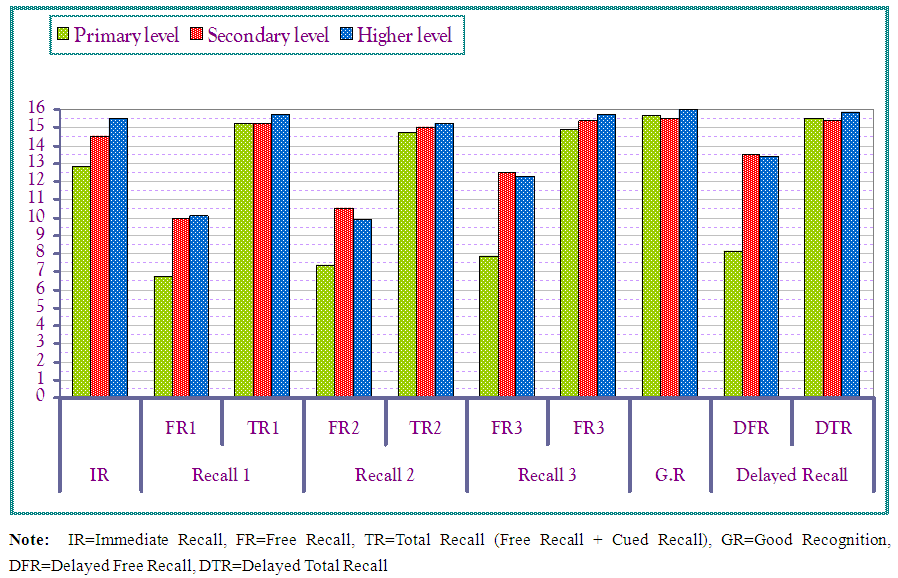

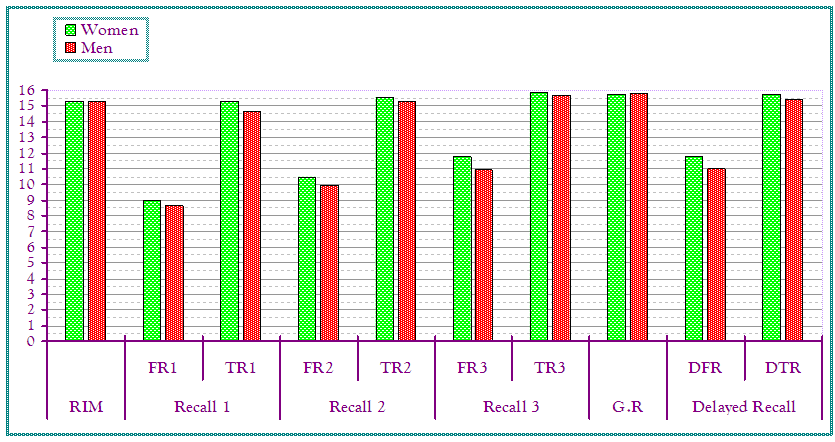

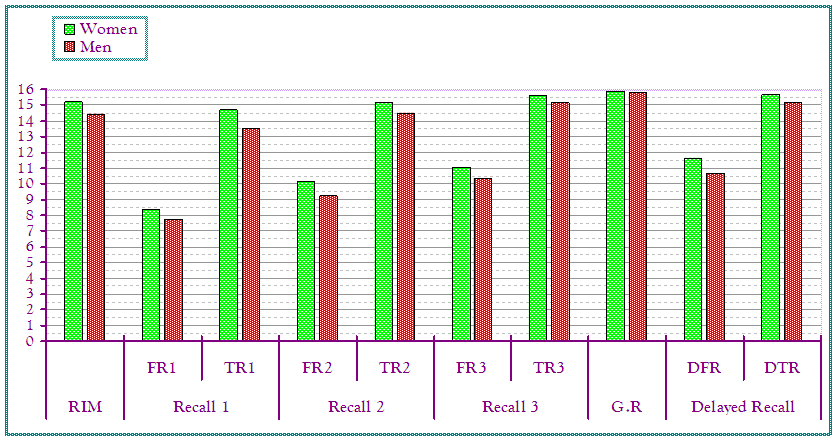

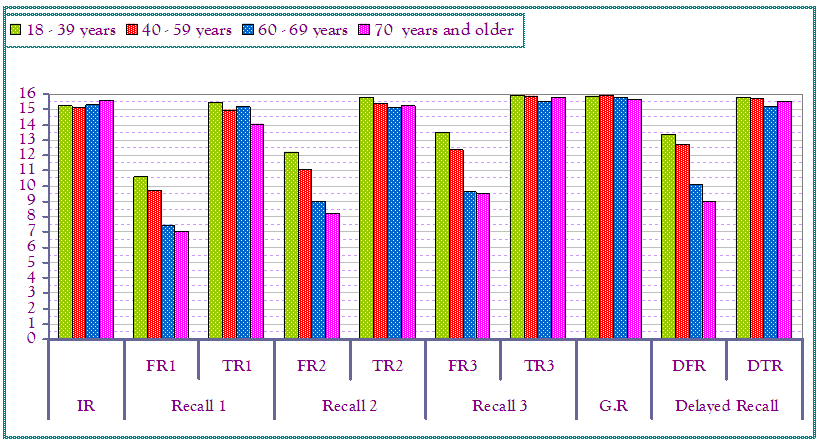

- After have been entered, the scores collected from 170 subjects have been analyzed using Microsoft-EXCEL. For their description, norms (averages with standard deviations) of the different quantitative variables studied were calculated based on the given form, gender (female, male), age (18-39, 40-59, 60-69, 70 years and older), and education (3-6, 7-10, 11 years and over) and there reported in tables and graphs. The extracted variables are: (a) Immediate Recall (IR); (b) Free Recall 1 (FR1); (c) Total Recall 1 (TR1 = free recall 1 + cued recall 1); (d) Free Recall 2 (FR2); (e) Total Recall 2 (TR2); (f) Free Recall 3 (FR3); (g) Total Recall 3 (TR3); (h) Total of 3 Free Recall (T3FR); (i) Total of 3 Total Recall (T3TR); (j) Good Recognition (GR); (k) Delayed Free Recall (DFR); (l) Delayed Total Recall (DTR).

|

| Figure 2. The results of the form 1 and 2 |

| Figure 3. The results of the form 1 by gender |

| Figure 4. The results of the form 2 by gender |

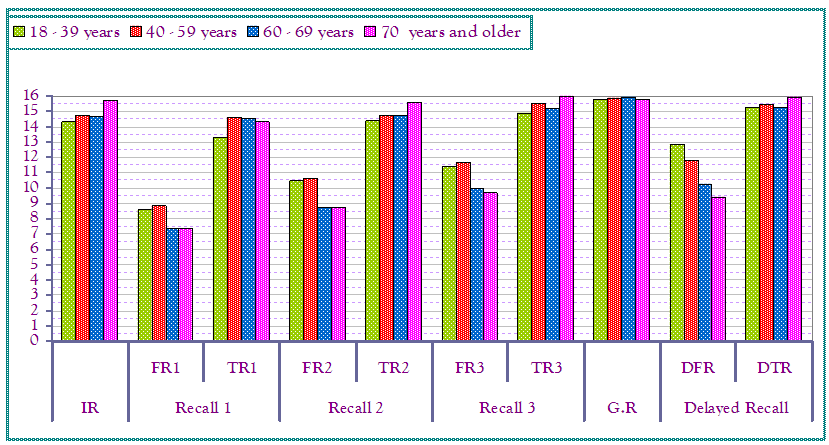

| Figure 5. The results of the form 1 by age |

| Figure 6. The results of the form 2 by age |

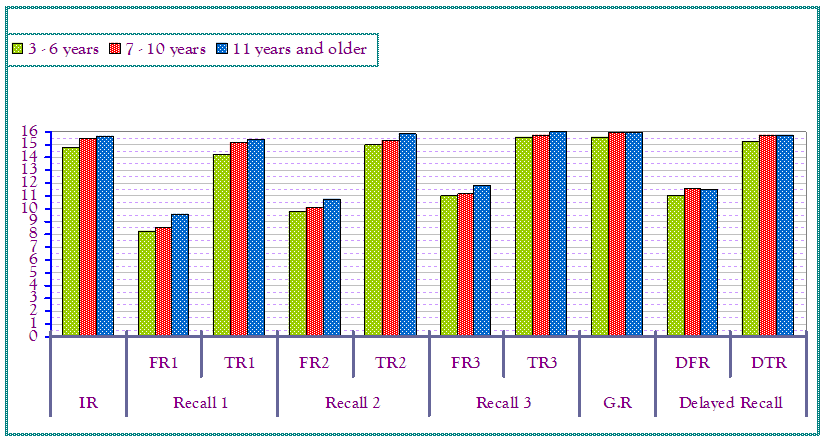

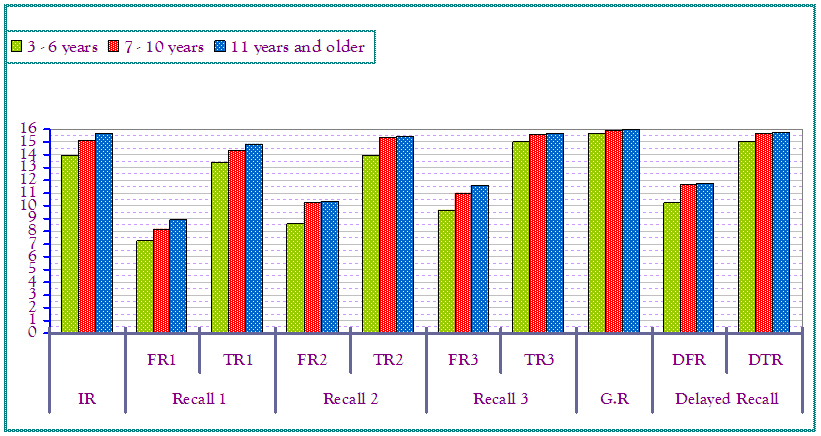

| Figure 7. The results of the form 1 by level of education |

| Figure 8. The results of the form 2 by level of education |

4. Discussion

- Before discussing, with a literature review, the value of the results obtained, it is important to mention that the analysis of the distribution of scores of different parameters of the adapted Arabic FCSRT shows that they can be classified into two distinct categories:Those whose score distribution follows the normal law or a law close to normal: the first category includes all the free recall (FR1, FR2, FR3 and DFR).Those whose distribution appears highly asymmetric and shows a "ceiling effect" or "floor" very strong: this second category includes the immediate recall (IR), total recall (TR1, TR2, TR3, DTR) and the score of good recognition (G.R). The cued recall were not considered in the analysis, since each cued recall is a component of the corresponding total recall.In both sample groups (form 1 and form 2) and as observed in the original English version [13], the French [15, 16], Spanish [14] and Italian adaptation [17], our subjects improved their performance between the first and the third free recall. The importance of recovery percentage reflected the effectiveness of semantic cueing in "normal" subjects. Similarly observed by these authors, our results are in line with our expectations: that memory performance in FCSRT for the basic shape decreases with age. Such effects are classic and as expected, at least on the psychometric level, the general intellectual efficiency decreases with age. Yet we did not find similar results for the parallel form, even opposite results for IR, TR1, TR2, TR3 and DTR scores.Concerning the effect of education on memory performance, the results corroborate the results of Van der Linden [15], Amieva [16], Pena-Casanova [14] and Frasson [17]. Indeed, the higher is the level of education more the performance is better; on the contrary, this effect was not found in the English standardization [13] because all individuals have a high level of education (more than 8 years of schooling). However, sex had no relevant influence on memory performance of our participants, the same conclusion is found in the literature [13, 15, 16, 14]. For example, in their study, Ivnik and colleagues [13] showed that gender and educational attainment explain only 2% of the variability of the scores FCSRT test. Roughly speaking, we can conclude that the performance of normal participants FCSRT adapted Arabic depend mainly on age and level of education.Our analysis also aimed to compare the two groups of subjects based on past form (the basic form or the parallel form). We found that these results are not homogeneous since they vary from one rcall to another. The average performances of the two groups are different for FR1, TR1, FR2, TR2, FR 3 and TR3; while they do not differ for G.R, DFR and DTR. If we accept the hypothesis of a strict similarity between the two groups in terms of mnemonic efficiency, these comparisons lead to the conclusion that the two lists are not strictly parallel, and, in general, the "basic list" is slightly easier than the "parallel list." This conclusion, however, has to be verified because the small number of subjects from which comparisons were made.The differences observed between our results and those of different normalizations mentioned in this paper can be explained by the difference in sample size, the difference between the age groups, the difference in socio-economic backgrounds or use school classes close or extreme.However, our results are characterized by the presence of a ceiling effect at IR, TR1, TR2, TR3, G.R, DTR and T3TR scores, the average scores for the latter two forms 1 and 2 are respectively 46, 08 (±2.18) and 44.34 (±4.61) for a maximum score of 48. The same effect is found in the work of Grober and Buschke [3], Tounsi & al [19] and the Van der Linden & al [15], total recall scores of non-demented persons were respectively 47.8 (±1.32), 46.9 (±1.12) and 46.45 (±1.28) always in a maximum score of 48 points.

5. Conclusions

- At the end of this study, we have developed a Moroccan version (Arabic) of the FCSRT taking into account the assumptions of the original version and the sociolinguistic variables of the Moroccan population. Indeed, the normative data in this version have shown that memory performance of normal participants depend mainly on age and level of education while sex had no significant influence. Of course, the results are likely to change, as the database will be enriched.However, in order to validate the normalization of this test (by determining its sensitivity and specificity) and to refine the diagnostic and discriminative power, this work should be completed by a comparative study comparing the memory performance of normal subjects with those of groups of patients with the following disorders: memory complaints, mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer's disease and cerebrovascular cognitive impairment, always taking into account the age, sex and level of education.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors are grateful to all subjects who participated in this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML