-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Brain and Cognitive Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1840 e-ISSN: 2163-1867

2014; 3(2): 39-43

doi:10.5923/j.ijbcs.20140302.02

Employing Natural Dentition to Rehabilitate a Patient Handicapped by the Effects of Brain Tuberculoma

Khurshid Mattoo1, Lakshya Yadav2, Pooja Arora3

1Department of Prosthodontics, College of dental sciences, Gizan University, Gizan, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

2Department of prosthodontics, King George medical college, KGM University, Lucknow, India

3Department of prosthodontics, Subharti dental college, Subharti University, Meerut, India

Correspondence to: Khurshid Mattoo, Department of Prosthodontics, College of dental sciences, Gizan University, Gizan, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Tuberculosis is still one of the primary challenges to health care workers. For patients with nervous system involvement, tubercular meningitis and intracranial tuberculomas are two most common manifestations. Following haematogenous spread, tuberculoma patients are often treated surgically which renders them partially or totally handicapped depending on the extent of surgical excision. This clinical case report describes a rare and a unique case of a patient who was handicapped as a result of surgical excision of brain tuberculoma in his late childhood. His dentition was utilized to fabricate a mouthstick appliance which was modified to hold accessories like pen, brush, rubber etc. once the prosthesis was fabricated the patient was referred to a psychomotor skill development program which helped the patient to gain independence.

Keywords: Appliance, Mandibular movements, Occlusion, Articulator

Cite this paper: Khurshid Mattoo, Lakshya Yadav, Pooja Arora, Employing Natural Dentition to Rehabilitate a Patient Handicapped by the Effects of Brain Tuberculoma, International Journal of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2014, pp. 39-43. doi: 10.5923/j.ijbcs.20140302.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Tuberculosis is still one of the biggest challenges to medical science as it is the most common cause of infection related death worldwide. [1] Most of the patients infected with its causative organism (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) do not develop active disease. It supposedly infects persons of all ages, including children. Tuberculosis may manifest with atypical clinical manifestations and delayed diagnosis may give rise to unexpected grave outcomes. Dissemination of the bacilli via the blood stream causes discrete foci in organs like lungs, liver, pleura, urinary tract, spleen and even central nervous system.Central nervous system involvement has frequently been reported secondary to tuberculosis elsewhere in the body, clinically in 19.6% of all patients with extra pulmonary tuberculosis. [2] Intracranial tuberculomas represent a common neurological disorder in developing countries like India, accounting for 10% to 30% of all intracranial masses. [1, 3] Tuberculous meningitis and intracranial tuberculomas are the two most frequent manifestations of neurotuberculosis [4, 5]. Tuberculomas tend to develop during and/or after the treatment of tubercular meningitis. [6-14] Most investigators presume that the appearance of new tuberculomas is an interplay between the host’s immune responses and the direct effects of mycobacterial products. [15-19].Tuberculomas develop following haematogenous dissemination of bacilli from an infection elsewhere in the body, usually the lung. Both inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses develop in the CNS following mycobacterial infection. [20, 21] Although intracranial tuberculoma is a potentially curable disorder, delay of diagnosis increases morbidity and mortality. [22] Unfortunately, clinical manifestations are non-specific [23, 24] and objective evidence of systemic tuberculosis or exposure to the disease may be absent in up to 70% of cases. [25] Clinical signs and symptoms depend largely on the extent of the disease within the brain, which range from localized neurological deficits, multiple cranial nerve palsies, convulsions, gliosis, internal hydrocephalus, papilloedema, unilateral or bilateral ptosis, superior rectus palsy, evidence of systemic tuberculosis and in severe cases tubercular meningitis. Symptoms vary according to the portion of the brain involved. Most of the lesions usually resolve completely with anti-tuberculosis therapy. [26] Surgical excision of the lesion is indicated in patients with mass effect and paradoxical enlargement of the tuberculomas [27, 28] or when tuberculoma involves spinal cord. [29] The effects of surgical excision of the tuberculoma depend on the area excised.Among the survivors of TBM, some form of neurological impairment afflicts approximately 20 to 30%. These impairments range from cranial nerve palsies, ophthalmoplegia, seizures, psychiatric disorders, ataxia to hemiparesis, blindness, deafness, and mental retardation. Poor neurological outcomes again can also be predicted based on the presenting stage of disease. [30-36] This clinical case report is of a young male patient who was rendered physically handicapped by tuberculoma of the brain during his childhood. The patient was keen to seek a solution to his problem of being dependent on others.

2. Clinical Report

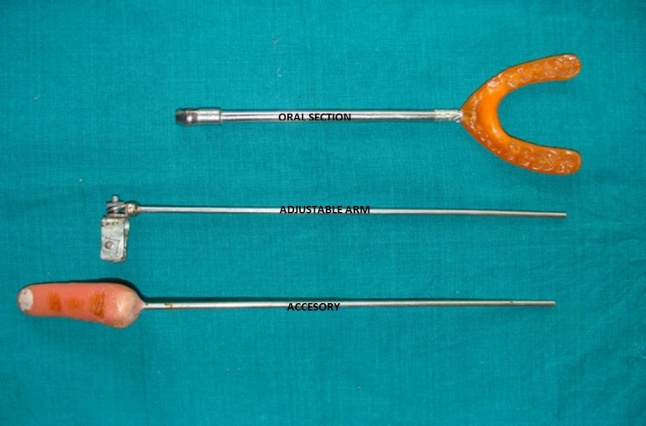

- A male patient, aged 32 years reported to the outpatient department of Prosthodontics with chief complaint of pain in the lower left first molar for 3 days. During his routine dental treatment, he had expressed his helplessness that was associated with his existing condition. He was asked to consult the department of Prosthodontics for possible solutions to his problem. Medical history of the patient and the prescriptions presented to the department revealed that during his childhood, he had developed tuberculosis of the brain, which was later surgically removed, after which patient had developed his existing state where his upper limbs were weak, short, deformed and atrophied. One of the eyes was protruding with disorientation in relation to the other eye. The patient's gait was also severely affected as his lower right leg was short and deformed. The patient’s right hand was short with severe medial inclination and severe atrophy of muscles. The natural dentition presented with class 1 malocclusion with anterior spacing in both maxillary and mandibular dentition. Psychological evaluation of the patient revealed depression with a negative attitude towards life. The patient was keen to seek a definite solution for his dependence upon his family members and his friends. Interview with his close friend revealed that the patient was looking for a job since last ten years, but was not able to get one. A treatment plan was devised which included oral prophylaxis, gingival curettage for treatment of localized periodontitis and finally the fabrication of a customized mouthstick appliance which could hold as many accessories as possible so that he could perform some functions in routine life. Primary impressions of the natural dentition were made (CA 37; Cavex, Haarlem, Holland), followed by the fabrication of a special tray for making the final impression with addition polyvinyl siloxane material (Reprosil, Dentsply/Caulk; Milford, DE, USA). Working casts were prepared using high strength dental stone. The maxillary and mandibular casts were then duplicated and one of them was mounted on a programmed semi adjustable articulator. Various mandibular movements of the patient were transferred to the articulator so that the mouth stick appliance would not counter any interference in centric or eccentric motion. The planned appliance had to be simple, adjustable, light in weight, easily inserted and removed, hygienic and not compromise with facial esthetics of the patient. The device was designed in three sections (Fig.1) as follows:-1. Oral section.2. Adjustable arm.3. Accessories.

| Figure 1. Sections of the mouthstick appliance [oral section, adjustable arm, accessory (from top to below)] |

3. Oral Section

- The oral section was fabricated in such a way that it would fit onto the occlusal surfaces of the maxillary and mandibular dentition to incorporate stability to the mouthstick appliance. After mounting the diagnostic casts on a semi adjustable articulator, analysis of the occlusion revealed premature and deflective contacts in centric and eccentric occlusion which were corrected by occlusal equilibration procedures. After correction of the existing occlusion, elastomeric impressions were made of maxillary and mandibular arches. The cast was remounted and the thickness of the oral section of the appliance was determined on the articulator by using the markings on the vertical pin. The thickness of the oral section was confined within the limits of interocclusal distance. To the wax pattern in the anterior region a small screw was secured which would engage component of the adjustable arm. The wax pattern was invested and the oral part was processed with heat cure acrylic. The oral part was finished, polished and then tried in the patient's mouth.

4. Adjustable Arm

- The adjustable arm was designed so that it can increase or decrease the length of the mouth stick appliance on the whole while at the same time it should be able to lock the various accessories in front of the adjustable arm (Fig. 1 and 2). The adjustable arm consists of a hollow cylindrical outer cover that has a diameter less than the diameter of the rod that is attached to the various accessories. This rod would not only fit into the cylinder, but also would allow flexibility in the overall length of the mouthstick appliance.

| Figure 2. Accessories in the form of a pen, brush, eraser, finger and a sucking tube |

5. Accessories

- To widen the scope of the patient to use the same appliance, different accessories in the form of a modified pen, pencil, painting brush, rubber, straw and an artificial finger were made (Fig 3). Each accessory was attached to the end of a metal rod. All the accessories would be fitting into the clamp that was provided at the end of the second part (the adjustable arm).

| Figure 3. Patient seen operating a lift with mouthstick appliance utilizing his dentition |

6. Instructions and Follow up

- After the mouthstick appliance was fabricated, all the accessories were tried for retention and stability in vitro. The patient was recalled and the fit of the mouthstick appliance was checked. All the accessories were checked for their retention and the stability. The finger accessory which could help him to operate the lift was tried in the actual lift (Fig.3). The patient was instructed to keep the acrylic artificial finger in plain water when not in use. The patients attendant was demonstrated the method to assemble and disengage each component. Instructions regarding maintenance were also given. After assessing the psychomotor skill of the patient, it was decided that he should undergo psychomotor skill training for a minimum period of one month. The patient was discharged and was put on a regular follow up for one year. After three months the patient visited the department to thank the involved staff as he was offered the job of a lift operating in a private college. During these three months, difficulties experienced by the patient and his attendant were related to assembling and disengaging the components. Patient desired some mechanism by which he would be able to assemble, engage and disengage all the accessories himself whereas the attendant felt that some components used to slip from the attachment and therefore needed some type of lock. People who had interviewed him were impressed with his conviction and dedication when they had seen him wearing the appliance. The mere fact that he had sought a solution to his problem was enough convincing for them, that he was the right person for the job. Significant improvement in mental attitude towards life was observed during subsequent patient visits which were confirmed by his family members.

7. Discussion

- Knowledge about the scope of other disciplines plays a significant role in uplifting any profession. An endodontist having basic knowledge about Prosthodontics prompted the patient to seek the opinion of the department of Prosthodontics where none of his actual dental treatment would have taken place. During his previous visits to many dentists, it was never highlighted by any dentist that a solution could be within the branch of Prosthodontics. Scope of various disciplines within the branch of dentistry should be known by every dental practitioner. Correction of existing occlusion to minimize and /or eliminate occlusal interferences before fabrication of the oral part of the appliance will ensure long term stability of the entire stomatognathic system. The thickness of the occlusal portion is determined by the amount of the freeway space that is present between the maxillary and mandibular dentition. This is particularly important if the appliance is used for a long time in the mouth for example painting or writing. Under no circumstances the thickness of the occlusal portion should violate the vertical dimension at rest as it will create muscle fatigue and later spasm. Moreover the patient will be reluctant to wear the appliance even for short periods.The locking mechanism for each component should not allow the rotation of the rod carrying the accessory within the cylinder. The mouthstick appliance should provide the patient to be less dependent on anyone. While working with the appliance patient should require minimum help from others. The length of the mouthstick appliance should be easily adjustable. This will allow the patient to minimize extension of the head towards the object.

8. Summary and Conclusions

- The mouthstick appliance provided excellent results for the patient over the period of time. The patient’s confidence improved even though it was difficult initially to work with it, but with regular practice the patient was able to master the art of working with the mouthstick appliance. The patient was also able to work as a lift operator which in fact has improved his lifestyle and social acceptance. For patients who are suffering from paralysis the mouthstick appliance is an essential tool to perform work by using their occlusion. Further refinement in designing is required that would enable such patients to assemble and disengage all accessories on their own.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors wish to acknowledge all those who were directly or indirectly linked to this article. The authors would also like to thank the director and the dean of the institute whose constant support towards research of all sorts are commendable.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML