-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Brain and Cognitive Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1840 e-ISSN: 2163-1867

2014; 3(1): 1-5

doi:10.5923/j.ijbcs.20140301.01

Verb and Noun Production in Aphasia: Evidence from Palestinian Arabic

Hisham Adam

American University of the Middle East, Kuwait

Correspondence to: Hisham Adam, American University of the Middle East, Kuwait.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Verbs and sentence production are usually impaired in individuals diagnosed with Broca’s aphasia. The current study investigates verb-noun production in a sample of spontaneous speech produced by four male Palestinian agrammatic aphasics. The results clearly revealed the dissociation between the production of nouns and the production of verbs. They also demonstrate that agrammatic aphasics produce nouns more than verbs. This finding has support from other studies conducted on other languages. The results also suggest that verb processing deficits among Broca’s aphasics can be interpreted in terms of semantic and syntactic complexity. However, the findings should only be regarded as preliminary in an area where further investigations are required, using larger number of subjects and stimuli in order to have a better understanding of the nature of language deficitsamong Palestinian agrammatics.

Keywords: Broca’s aphasia, Agrammatism, Palestinian arabic, Verb-noun dissociation in aphasia

Cite this paper: Hisham Adam, Verb and Noun Production in Aphasia: Evidence from Palestinian Arabic, International Journal of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2014, pp. 1-5. doi: 10.5923/j.ijbcs.20140301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Verb production and comprehension in addition to word retrieval difficulties are found to be challenging for Broca’s aphasic speakers (Caramazza & Hillis, 1991; Kambanaros, 2010; Dragoy & Bastiaanse, 2010). Broca’s aphasic speech is characterized by fewer lexical verbs that lack inflections (Bastiaanse, Jonkers, & Moltmaker-Osinga, 1996). Comprehension and production of verbs and nouns in agrammatic aphasics have been widely investigated (Menn & Obler, 1990; 1998; Thompson, Riley, den Ouden, Meltzer-Asscher, & Lukic, 2012). However, other studies demonstrate the existence of verb retrieval impairments in non-agrammatic aphasics (Jonkers & Bastiaanse, 1998). The results also indicate that not all verbs types have the same degree of difficulty for Broca’s aphasics (Kiss, 2000; McAllister, Bachrach, Waters, Michaud, & Caplan, 2009). Some studies demonstrated that agrammatic subjects perform better in naming objects than actions, whereas fluent aphasics such as anomics or Wernicke’s aphasics, display the opposite pattern (Miceli, Silveri, Nocentini, & Caramazza, 1988). In fact, because of the importance of verbs in sentence production and comprehension, they must be tested to arrive at a better understanding of the aphasic deficits at sentence level (Berndt, Haendiges, Mitchum, & Sandson, 1997).Some studies also displayed dissociation between nouns and verb processing (Thompson & Lee, 2009; Berndt et al., 1997). Research has also revealed that some agrammatic subjects demonstrated a selective deficit in verb production. In a study conducted by Thompson and Shapiro et al. (1997) on agrammatic patients, verb retrieval difficulty in verb naming and in sentence production has been reported. According to several studies, verb retrieval can be due either to mis-selection of the lexical item or inability to retrieve it, leading to the production of sentences lacking the target verb (Rochon et al., 2005). Luria (1966) mentioned some types of verbs that were difficult to comprehend for aphasics. She reported that action verbs that are transacted from one entity to another (to do for someone) were relatively difficult to perform because they require logico-grammatical operations that were found to be disturbed in the aphasic subjects. Considering this notion, the more information the picture contains, the more spatio-temporal relations need to be accessed. In addition, the way in which the action is performed (whether it done with the hands, the total body or with an instrument) affects the agrammatic patient’s performance (Kambanaros, 2010; Dickey & Thompson, 2007).

2. The Present Study

2.1. Significance of the Study

- Much research on agrammatism has been conducted, mainly on English-speaking aphasic subjects. For a long time, the results of these studies were believed to be universal, and were consequently used as a reference for non-English - speaking aphasics. Palestinian Arabic was less examined and investigated. So, the current investigation aims at filling this gap by highlighting the main symptoms characterizing verb and noun production by Palestinian agrammatic subjects and consequently contributing to a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms of agrammatism. The results may also help to improve clinical awareness of language disorders in Palestine.

2.2. The Aims of the Study

- The current study aims to (a) investigate verb and noun production by Palestinian agrammatic subjects; (b) to examine whether or not there is a dissociation between verb and noun production; and (c) to examine the extent to which the production deficits of nouns and verbs in Palestinian agrammatics are consistent with findings reported from other languages.

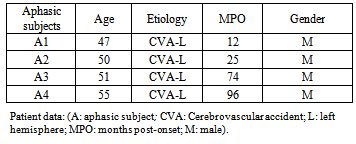

2.3. Subjects

- Four male agrammatic Palestinians residing in the West Bank participated in the study. The participants were diagnosed as Broca’s aphasics using the Jordanian Arabic version of the Bilingual Aphasia Test (Paradis, 1987). All participants were right-handed and presented with left hemisphere lesion at least six months prior to testing. They revealed typical symptoms of Broca’s aphasia, including non-fluent, effortful and telegraphic speech. As shown in Table 1, the ages of the participants ranged from 47 to 55 years. The time post-onset ranged from one to eight years, and their number of educational years ranged from 10 to 15. Visual and auditory systems functioned to a sufficient degree to complete the experimental tasks of the study. Four native speakers with no language or speech deficits served as the control group.

|

2.4. Task

- Verb and noun production features were examined using picture description. The aphasic participants were presented with the “cookie theft picture” from the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (Goodglass & Kaplan, 1983). Participants were instructed to tell a story about the picture, using the phrase “ʔi ħki” (“Say”), for approximately 80 seconds. Their output was recorded.

3. Results and Discussion

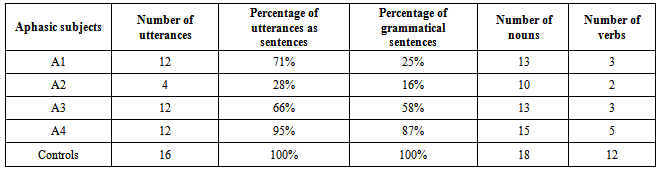

- Results are shown in Table 2. All subjects, except A2 produced 12 utterances. However, the analysis revealed that only few utterances were grammatically correct, where verb-tense consistency was presented. A2, who was found to be the most severe agrammatic, produced 28% of sentences. In contrast, A1 and A3 got scores of 71% and 66% respectively. The results also revealed different scores on grammatical sentences. For example, A2’s score was 16% while A1 got 25%. In contrast, A3 produced 58%, while A4 was 87%. Furthermore, the results showed that noun production ranged from 8 to 15, while subjects scored from 2 to 5 for verb production.The results clearly reveal the difference between the percentage of utterances as sentences and that of grammatical sentences, as well as the dissociation between the production of nouns and the production of verbs.Consistent with many findings across other languages, our analysis of verb production has shown a frequent deletion of verbs. However, verb deletion is not a distinguishable feature of the Palestinian aphasics. The following are some examples of verb productions obtained from their spontaneous speech. 1. [walad ……….. Bluzeh] [boy… blouse] for [al walad jalbisu lib blusa] “(mas) the boy wearing the blouse”2. [mrah ……

…… majeh] [woman… trees… water] for [marah tasqie

…… majeh] [woman… trees… water] for [marah tasqie  bil maay] “(fem) woman watering trees with water” (The woman is watering the trees with water)3. [sajja:ra…….

bil maay] “(fem) woman watering trees with water” (The woman is watering the trees with water)3. [sajja:ra…….  [car… street] for [sajja:ra taqifu

[car… street] for [sajja:ra taqifu  “(fem) car is stopped at the street” (The car is stopped at the street)Many factors affect the performance of the agrammatic patients in verb retrieval in action naming or in spontaneous speech tasks. Many investigations of the production and processing of lexical verbs by subjects with different types of aphasia are relatively restricted to action naming compared to object naming (Miceli et. al, 1988). This means that in action naming, the patient is instructed to say which action is being performed in a picture, thus increasing the chance of eliciting a verb. However, in object naming, the production of a noun is elicited.

“(fem) car is stopped at the street” (The car is stopped at the street)Many factors affect the performance of the agrammatic patients in verb retrieval in action naming or in spontaneous speech tasks. Many investigations of the production and processing of lexical verbs by subjects with different types of aphasia are relatively restricted to action naming compared to object naming (Miceli et. al, 1988). This means that in action naming, the patient is instructed to say which action is being performed in a picture, thus increasing the chance of eliciting a verb. However, in object naming, the production of a noun is elicited.

|

[push] in a picture description task, since they have to process intra-relationships including, for example, the location of the pusher and the pushee. Furthermore, our agrammatic subjects exhibited poor performance with reverse-role verbs, e.g.

[push] in a picture description task, since they have to process intra-relationships including, for example, the location of the pusher and the pushee. Furthermore, our agrammatic subjects exhibited poor performance with reverse-role verbs, e.g.  [to buy] and

[to buy] and  [to sell], and opposite-meaning verbs, e.g.

[to sell], and opposite-meaning verbs, e.g.  [to stand] and

[to stand] and  [to set down]. These findings are consistent with results reported by Breedin and Martin (1996), who studied verb type and its predictable influence on verb comprehension.The non-fluent subjects, as in the current study, revealed great difficulty with reverse-role verbs in contrast to the other types. Those subjects performed imprecisely on these verbs because they are considered semantically complex. This difficulty could suggest that the aphasics exhibit particular problems in assigning thematic roles of verbs (Rochon et al., 2005). However, this problem affects not only verb production but also verb comprehension. This means that they exhibited a general deficit in the assignment of thematic roles concerning both comprehension and production.The influence of the verb frequency on the agrammatic aphasics’ performance in verb retrieval was found to be crucial. Low-frequency verbs are less difficult than high-frequency ones. This supports the idea that the most frequent words in a language, especially the grammatical function words, tend to be omitted by the agrammatic aphasics, whereas words with much lower frequency tend to be spared (Love & Oster, 2002; Berndt et al., 1997). The agrammatic patients in the current study tended to produce nouns more than verbs. This finding has support from other studies (Miceli et al., 1984). While some results revealed that verbs may or may not be more difficult than nouns for aphasics, others demonstrated that there may or may not be a qualitative difference between the performance of fluent and non-fluent aphasics (Daniele, Giustolisi, Silveri, Colosimo, & Gainotti, 1994).Based on the poorness of verb retrieval, Miceli, Silveri, Villa, and Caramazza (1984) suggested that some structural deficits found in agrammatic patients might be due to their poor retrieval of verbs. That means that their inefficient ability to access verbs could cause impairments in sentence structure during production.In the spontaneous speech of the Palestinian agrammatic subjects, the occurrence of verbs was limited to the degree that one can say that verbs are frequently deleted and only a limited number of them are used. However, some verbs were used, a finding consistent with other results (Kremin, 1994). Deletion and nominalization of verbs are not unique to Arabic, but match findings reported from other languages (Menn & Obler, 1990).In fact, word retrieval difficulties are a frequent consequence of brain damage to subjects. These impairments are manifested in spontaneous as well as in structured language tasks. Many investigations have indicated that non-fluent aphasic subjects exhibit particular difficulties in accessing and retrieving verbs in contrast to nouns.Thus, it is usually noticed that the agrammatic subjects produced fewer verbs than nouns. The omission of verbs could be related to the syntactic processing ability, which involves the positioning of verbs in the syntactic frame. Support for the frequent omission of verbs comes from the inflectional languages such as Hebrew and Italian (Menn & Obler, 1990). In the case of Arabic, affixation is a derivational process. For instance, the root “r s m” consists of three discontinuous radicals:[rasama] He drew[tarsumu] She is drawing [jarsumu] He is drawing[narsumu] We are drawing[jarsuma:ni] They are drawing (dual for masculine and feminine)

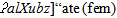

[to set down]. These findings are consistent with results reported by Breedin and Martin (1996), who studied verb type and its predictable influence on verb comprehension.The non-fluent subjects, as in the current study, revealed great difficulty with reverse-role verbs in contrast to the other types. Those subjects performed imprecisely on these verbs because they are considered semantically complex. This difficulty could suggest that the aphasics exhibit particular problems in assigning thematic roles of verbs (Rochon et al., 2005). However, this problem affects not only verb production but also verb comprehension. This means that they exhibited a general deficit in the assignment of thematic roles concerning both comprehension and production.The influence of the verb frequency on the agrammatic aphasics’ performance in verb retrieval was found to be crucial. Low-frequency verbs are less difficult than high-frequency ones. This supports the idea that the most frequent words in a language, especially the grammatical function words, tend to be omitted by the agrammatic aphasics, whereas words with much lower frequency tend to be spared (Love & Oster, 2002; Berndt et al., 1997). The agrammatic patients in the current study tended to produce nouns more than verbs. This finding has support from other studies (Miceli et al., 1984). While some results revealed that verbs may or may not be more difficult than nouns for aphasics, others demonstrated that there may or may not be a qualitative difference between the performance of fluent and non-fluent aphasics (Daniele, Giustolisi, Silveri, Colosimo, & Gainotti, 1994).Based on the poorness of verb retrieval, Miceli, Silveri, Villa, and Caramazza (1984) suggested that some structural deficits found in agrammatic patients might be due to their poor retrieval of verbs. That means that their inefficient ability to access verbs could cause impairments in sentence structure during production.In the spontaneous speech of the Palestinian agrammatic subjects, the occurrence of verbs was limited to the degree that one can say that verbs are frequently deleted and only a limited number of them are used. However, some verbs were used, a finding consistent with other results (Kremin, 1994). Deletion and nominalization of verbs are not unique to Arabic, but match findings reported from other languages (Menn & Obler, 1990).In fact, word retrieval difficulties are a frequent consequence of brain damage to subjects. These impairments are manifested in spontaneous as well as in structured language tasks. Many investigations have indicated that non-fluent aphasic subjects exhibit particular difficulties in accessing and retrieving verbs in contrast to nouns.Thus, it is usually noticed that the agrammatic subjects produced fewer verbs than nouns. The omission of verbs could be related to the syntactic processing ability, which involves the positioning of verbs in the syntactic frame. Support for the frequent omission of verbs comes from the inflectional languages such as Hebrew and Italian (Menn & Obler, 1990). In the case of Arabic, affixation is a derivational process. For instance, the root “r s m” consists of three discontinuous radicals:[rasama] He drew[tarsumu] She is drawing [jarsumu] He is drawing[narsumu] We are drawing[jarsuma:ni] They are drawing (dual for masculine and feminine) I am drawing[rasamtu] I draw”[rasm] The process of drawing[rasma] drewAs we can see, the vowels are inserted between the constants in order to pronounce the root. The stem in Arabic consists of the “C” radicals and vowel patterns. Therefore, the prediction of deleting the inflection segments and pronouncing the root by the agrammatic Palestinian subjects is impossible since it is not a free morpheme. The Arabic agrammatic patients added affixes to the verb; however, they sometimes used the wrong inflectional morphemes: 1. [akal binit Xubz] “ate (mas) girl bread” for

I am drawing[rasamtu] I draw”[rasm] The process of drawing[rasma] drewAs we can see, the vowels are inserted between the constants in order to pronounce the root. The stem in Arabic consists of the “C” radicals and vowel patterns. Therefore, the prediction of deleting the inflection segments and pronouncing the root by the agrammatic Palestinian subjects is impossible since it is not a free morpheme. The Arabic agrammatic patients added affixes to the verb; however, they sometimes used the wrong inflectional morphemes: 1. [akal binit Xubz] “ate (mas) girl bread” for  albint

albint  the girl the bread”2.

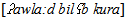

the girl the bread”2.  “boys play (sing) football” for

“boys play (sing) football” for  “The boys (pl) are playing football”3. [jaktub] “(fem) writing” for [taktub] “(mas) writing”Thus, the lexical entries of verbs have plentiful different elements of information that need to be retrieved and taken in during the process of comprehension, retrieval and the production. They include information about meaning, verb morphology, syntactic sub-categorization, argument structure and thematic properties. As a whole, these factors significantly influence the abilities of the aphasic subjects in verb processing and verb morphology, verb-argument structure, and thematic information (Black, Nickels & Byng, 1991).Several theories and interpretations have been raised in order to understand the nature and correlations of verb processing difficulty among aphasics (Miceli et al., 1984). Some studies relate the retrieval deficit to an inability to retrieve the correct lexical form of the verb from the lexicon where verbs are stored (Miceli, et. al, 1984) Accordingly, verbs and nouns must be retrieved and activated from different subcomponents of the lexicon. The deficit is apparent not only in the production of verbs but also in their comprehension, since there is a separation in the network for input and output to and from the sub-compartments for nouns and verbs in the lexicon.Evidence of the effect of syntax on verb retrieval problems in aphasics suggests that the verb retrieval process requires a retrieval of all information embedded in the verb, and that this is impaired (Zingeser & Berndt, 1990). Furthermore, one of the reasons for this difficulty is that verbs carry more syntactic information than nouns, thus increasing the difficulty of retrieving them from the lexicon. Berndt et Al. (1997) refer to a number of correlations that could affect verb retrieval including sentence structure, the attitude of words in sentences and the mean length of sentence.Various studies have exhibited significant effects of site of lesion on verb retrieval among aphasic subjects. Miozzo, Soardi and Cappa (1994) argued that the conceptual representation of actions is stored in or near the motor cortex in the frontal part of the brain since the execution of actions is controlled in this part of the brain, so that damage to this area causes a deficit in verb retrieval.As verb retrieval is a staged process moving from lemma to another, Bastiaanse (1991) indicated that Broca’s aphasics suffer from problems in retrieving the verb lemmas from the lexicon because the corresponding grammatical form works insufficiently. To conclude, the property that most saliently concerns verb retrieval disability is the highly disturbed selectivity of verbs and nouns.Neuroanatomical studies indicate an absence of separate cortical representations for verbs and nouns. In their reaction time experiment, Gomes et al. (1997) found no electrophysiological indices for different anatomical representations for nouns and verbs in normal speakers. By examining verb retrieval abilities across agrammatic aphasics, Damasio and Tranel (1993) found thatverb impairment was associated with damage extending or limited to the left prefrontal cortex. Nevertheless, other findings from neurocognitive studies dealing with brain-damaged individuals showed that left temporal damage is associated with noun loss while the left prefrontal cortex is associated with verb loss (McCarthy & Warrington, 1985; Zinger & Berndt, 1990; Caramazza & Hillis, 1991). Thus, there is a growing body of evidence coming from normal speakers indicating that the left frontal lobe is associated with verb performance (Grossman, Cooke, DeVita, Alsop, Detre, & Gee, 2002). The proposal that verbs convey an abundant amount of information demanding a particular neuronal activation in order to retrieve them did not support the idea of dissociation. Thus, however, both nouns and verbs imply information about semantic features but only verbs impart information about grammatical and thematic information.It is important emphasize the fact that verb processing can trigger the activation of multiple executive processing demands such as selective attention, working memory, planning, and inhibitory control (Grossman et. al, 2002). For example, using a verb correctly requires accessing the corresponding grammatical information associated with verb awareness of the performer and receiver of the action of the verb, and mentally maintaining and implementing this information to construct a sentence. Moreover, verb recognition and retrieval is inherently a process of discriminating the target verb from other candidate verbs by inhibiting other competing verb information that may be activated during the processing of a sentence’s context. Verb processing is assumed to take place through spreading activation in a network of elements representing verbs, such as their sub-components, meanings and their conceptual representation.Once again, several neural studies addressed the neural role of the frontal regions of the cortex in coordinating and executing the large amount of information required for correct verb use (Miceli et al., 1988). Accordingly, on account of their site of lesion in the inferior frontal lobe, Broca’s aphasics exhibited complications in the correct use of verbs and a predominance of grammatical impairments.Zingeser and Berndt (1990) suggested that the syntactic deficit in Broca’s aphasics might be a determinant cause because of the fact that verbs bear more syntactic and semantic information than nouns. Therefore, the question remains why verbs are more difficult to retrieve than nouns in both Broca’s aphasics and anomics. As is well known, verbs and nouns differ syntactically, leading, as one might expect, to different performance in action and object naming.In his study, Gentner (1981) identified some differences between verbs and nouns that could contribute to this difficulty. For example, verbs were found to be harder to be reminded of than nouns. Moreover, based on language acquisition, verb meanings are acquired later than noun meanings by children. To conclude, Broca’s aphasics demonstrated more problems in producing verbs than nouns. In accordance with results from other languages, verb deletion predominates over noun deletion.

“The boys (pl) are playing football”3. [jaktub] “(fem) writing” for [taktub] “(mas) writing”Thus, the lexical entries of verbs have plentiful different elements of information that need to be retrieved and taken in during the process of comprehension, retrieval and the production. They include information about meaning, verb morphology, syntactic sub-categorization, argument structure and thematic properties. As a whole, these factors significantly influence the abilities of the aphasic subjects in verb processing and verb morphology, verb-argument structure, and thematic information (Black, Nickels & Byng, 1991).Several theories and interpretations have been raised in order to understand the nature and correlations of verb processing difficulty among aphasics (Miceli et al., 1984). Some studies relate the retrieval deficit to an inability to retrieve the correct lexical form of the verb from the lexicon where verbs are stored (Miceli, et. al, 1984) Accordingly, verbs and nouns must be retrieved and activated from different subcomponents of the lexicon. The deficit is apparent not only in the production of verbs but also in their comprehension, since there is a separation in the network for input and output to and from the sub-compartments for nouns and verbs in the lexicon.Evidence of the effect of syntax on verb retrieval problems in aphasics suggests that the verb retrieval process requires a retrieval of all information embedded in the verb, and that this is impaired (Zingeser & Berndt, 1990). Furthermore, one of the reasons for this difficulty is that verbs carry more syntactic information than nouns, thus increasing the difficulty of retrieving them from the lexicon. Berndt et Al. (1997) refer to a number of correlations that could affect verb retrieval including sentence structure, the attitude of words in sentences and the mean length of sentence.Various studies have exhibited significant effects of site of lesion on verb retrieval among aphasic subjects. Miozzo, Soardi and Cappa (1994) argued that the conceptual representation of actions is stored in or near the motor cortex in the frontal part of the brain since the execution of actions is controlled in this part of the brain, so that damage to this area causes a deficit in verb retrieval.As verb retrieval is a staged process moving from lemma to another, Bastiaanse (1991) indicated that Broca’s aphasics suffer from problems in retrieving the verb lemmas from the lexicon because the corresponding grammatical form works insufficiently. To conclude, the property that most saliently concerns verb retrieval disability is the highly disturbed selectivity of verbs and nouns.Neuroanatomical studies indicate an absence of separate cortical representations for verbs and nouns. In their reaction time experiment, Gomes et al. (1997) found no electrophysiological indices for different anatomical representations for nouns and verbs in normal speakers. By examining verb retrieval abilities across agrammatic aphasics, Damasio and Tranel (1993) found thatverb impairment was associated with damage extending or limited to the left prefrontal cortex. Nevertheless, other findings from neurocognitive studies dealing with brain-damaged individuals showed that left temporal damage is associated with noun loss while the left prefrontal cortex is associated with verb loss (McCarthy & Warrington, 1985; Zinger & Berndt, 1990; Caramazza & Hillis, 1991). Thus, there is a growing body of evidence coming from normal speakers indicating that the left frontal lobe is associated with verb performance (Grossman, Cooke, DeVita, Alsop, Detre, & Gee, 2002). The proposal that verbs convey an abundant amount of information demanding a particular neuronal activation in order to retrieve them did not support the idea of dissociation. Thus, however, both nouns and verbs imply information about semantic features but only verbs impart information about grammatical and thematic information.It is important emphasize the fact that verb processing can trigger the activation of multiple executive processing demands such as selective attention, working memory, planning, and inhibitory control (Grossman et. al, 2002). For example, using a verb correctly requires accessing the corresponding grammatical information associated with verb awareness of the performer and receiver of the action of the verb, and mentally maintaining and implementing this information to construct a sentence. Moreover, verb recognition and retrieval is inherently a process of discriminating the target verb from other candidate verbs by inhibiting other competing verb information that may be activated during the processing of a sentence’s context. Verb processing is assumed to take place through spreading activation in a network of elements representing verbs, such as their sub-components, meanings and their conceptual representation.Once again, several neural studies addressed the neural role of the frontal regions of the cortex in coordinating and executing the large amount of information required for correct verb use (Miceli et al., 1988). Accordingly, on account of their site of lesion in the inferior frontal lobe, Broca’s aphasics exhibited complications in the correct use of verbs and a predominance of grammatical impairments.Zingeser and Berndt (1990) suggested that the syntactic deficit in Broca’s aphasics might be a determinant cause because of the fact that verbs bear more syntactic and semantic information than nouns. Therefore, the question remains why verbs are more difficult to retrieve than nouns in both Broca’s aphasics and anomics. As is well known, verbs and nouns differ syntactically, leading, as one might expect, to different performance in action and object naming.In his study, Gentner (1981) identified some differences between verbs and nouns that could contribute to this difficulty. For example, verbs were found to be harder to be reminded of than nouns. Moreover, based on language acquisition, verb meanings are acquired later than noun meanings by children. To conclude, Broca’s aphasics demonstrated more problems in producing verbs than nouns. In accordance with results from other languages, verb deletion predominates over noun deletion.4. Conclusions

- The results clearly revealed the dissociation between the production of nouns and the production of verbs. The agrammatic patients in the current study tended to produce nouns better than verbs. This finding has support from other studies (Miceli et al., 1984). The occurrence of verbs was very limited to the degree that one can say that the verbs are frequently deleted and only a limited number are produced. However, some verbs were produced, consistent with other results (Kremin, 1994). Consequently, verb deletion and nominalization of the verb are not unique to Arabic, but match findings reported from other languages. However, it must be mentioned that in the current study preliminary results are reported which will be diversified, continued and completed by increasing the number of patients with Broca’s aphasia. The finding of the current study may have clinical implications, suggesting that specific verbs and nouns might be targeted in the therapy plans and approaches.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML