Noorain Batool, Mohammad Akram

Department of Sociology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India

Correspondence to: Noorain Batool, Department of Sociology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

India has a large burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases. There is a need for effective treatment of diseases and illness conditions for improving life expectancy and quality of life. Treatment refers to the interventions made to regain the state of well-being or health from a state of illness and sickness. Although several agencies provide national and state level health related data in India, there is dearth of specific data at micro or local level. It is very important to understand health behavior of people at micro level for having fair intervention at macro level. Hence, this study is conducted in urban areas of Aligarh district of Uttar Pradesh in India to study the prevalence pattern of communicable and non-communicable diseases and the prevailing treatment patterns. This study is conducted in selected urban wards of Aligarh city of Uttar Pradesh, India. The primary data is collected from 300 respondents by using Interview Schedule. The respondents were asked to name the disease that they suffered from within last one year and the treatment method that they followed. We found that the proportion of respondents suffering from communicable diseases (58.3%) was more than the proportion of respondents suffering from non- communicable disease (41.7%). Further, the prevalence of communicable disease among the male respondents was more than the female respondents. Under the category of non-communicable disease, the prevalence was more among the female respondents. Communicable diseases pose a serious threat to individuals’ health and have the potential to threaten collective human security and the spread of corona virus in last two years has proved this again. Current burdens of communicable diseases make these a continuing threat to public health in all countries. India must orient the health system towards prevention, screening, early intervention and new treatment modalities with the aim to reduce the burden of communicable as well as non- communicable disease as envisaged in the globally accepted Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) also.

Keywords:

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Illness, Disease, Illness Behavior, Treatment

Cite this paper: Noorain Batool, Mohammad Akram, Illness and Treatment Pattern among Urban People in India: A Sociological Study in Aligarh City of Uttar Pradesh, International Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. 12 No. 1, 2022, pp. 19-30. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20221201.03.

1. Introduction

The United Nations General Assembly has adopted seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The SDGs are the blueprints to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all. Health is one of these seventeen goals and the SDGs show a strong commitment to public health. The 2030 Agenda states: “To promote physical and mental health and well-being, and to extend life expectancy for all, we must achieve universal health coverage and access to quality health care. No one must be left behind.” The goal number 3 of the SDGs which is health related goal categorically states: “Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” [1]. The health goal talks about the targets related to reduction in maternal mortality ratio (MMR) and infant mortality rate (IMR), ending preventable premature mortalities caused because of communicable and non-communicable diseases, ending the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combating hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases and few other related targets.The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development recognizes Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) as a major challenge for sustainable development. As part of the Agenda, Heads of State and Government committed to develop ambitious national responses, by 2030, to reduce by one-third premature mortality from NCDs through prevention and treatment (SDG target 3.4). According to the fact sheet of World Health Organization (WHO), NCDs kill 41 million people each year, equivalent to 71% of all deaths globally. Each year, more than 15 million people die from a NCD between the ages of 30 and 69 years; 85% of these “premature” deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries and cardiovascular diseases account for most NCD deaths, or 17.9 million people annually, followed by cancers (9.3 million), respiratory diseases (4.1 million), and diabetes (1.5 million) [2]. At the global level, in 2017, more than 60% of the burden of disease resulted from NCDs, with 28% from communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional diseases, and just over 10% from injuries [3].Bonita, et al., in “Basic Epidemiology”, published by WHO mention that communicable diseases pose a serious threat to individuals’ health and have the potential to threaten collective human security. The estimated global burden of communicable diseases, in the pre-COVID-19 era, was dominated by HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria [4]. As part of the Agenda of SDGs, Heads of State and Government committed to develop ambitious national responses to the overall implementation of this Agenda by 2030 and end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases (SDG target 3.3) [1]. According to WHO fact sheet, HIV continues to be a major global public health issue, having claimed 36.3 million [27.2–47.8 million] lives so far. There were an estimated 37.7 million [30.2–45.1 million] people living with HIV at the end of 2020, over two thirds of whom (25.4 million) are in the WHO African Region. In 2020, 680 000 [480 000–1.0 million] people died from HIV related causes and 1.5 million [1.0–2.0 million] people acquired HIV. A total of 1.5 million people died from tuberculosis (TB) in 2020. Worldwide, TB is the 13th leading cause of death and the second leading infectious killer after COVID-19. In 2020, an estimated 10 million people fell ill with TB worldwide: 5.6 million men, 3.3 million women and 1.1 million children. Globally, TB incidence is falling at about 2% per year and between 2015 and 2020 the cumulative reduction was 11%. This was over half way to the End TB Strategy milestone of 20% reduction between 2015 and 2020. Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by parasites that are transmitted to people through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. In 2020, there were an estimated 241 million cases of malaria worldwide. The estimated number of malaria deaths stood at 627 000 in 2020 [5].Corona virus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus [6]. Globally, as of 25 January 2022, there have been 352,796,704 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 5,600,434 deaths, reported to WHO. As of 23 January 2022, a total of 9,620,105,525 vaccine doses have been administered [7]. In the present context, COVID-19 is appearing to be the greatest threat to mankind globally. COVID-19 is highly communicable and it is frequently undergoing mutations and the world is witnessing existence of multiple variants of the virus. Although the world has vigorously launched the vaccination program but we know little about the long-term consequences of the virus.India is a union of 28 states and 8 union territories. As of 2011, with an estimated population of 1.2 billion, India is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world [8]. Uttar Pradesh is an Indian state nestled in the northern part of the country. It's also home to 200 million people, making it India's most populous state by far, as well as the biggest state inside a country in the world [9]. As per details from Census of India 2011, total population of Uttar Pradesh is 199,812,341 of which male and female are 104,480,510 and 95,331,831 respectively. Out of total population of Uttar Pradesh, 22.27% people live in urban regions and around 77.73 % live in the villages of rural areas [10].It has been observed that the non-communicable diseases dominate over communicable in the total disease burden of the country. In a report of India Council of Medical Research (ICMR), titled India: Health of the Nation’s States: The India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative (2017), it is observed that the disease burden due to communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases, as measured using disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), dropped from 61% to 33% between 1990 and 2016. In the same period, disease burden from non-communicable diseases increased from 30% to 55%. The epidemiological transition, however, varies widely among Indian states: 48% to 75% for non-communicable diseases, 14% to 43% for infectious and associated diseases, and 9% to 14% for injuries [11].In a report of India Council of Medical Research (ICMR) titled as India: Health of the Nation’s States: The India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative (2017), it is observed that life expectancy is considered to be the most commonly used indicator of health. In India, life expectancy at birth improved from 59.7 years in 1990 to 70.3 years in 2016 for females, and from 58.3 years to 66.9 years for males. There were, however, continuing inequalities between states, with a range of 66.8 years in Uttar Pradesh to 78.7 years in Kerala for females, and from 63.6 years in Assam to 73.8 years in Kerala for males in 2016. The per person disease burden measured as DALY rate dropped by 36% from 1990 to 2016 in India, after adjusting for the changes in the population age structure during this period. But there was an almost two-fold difference in this disease burden rate between the states in 2016, with Assam, Uttar Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh having the highest rates, and Kerala and Goa the lowest rates. While the disease burden rate in India has improved since 1990, it was 72% higher per person than in Sri Lanka or China in 2016. The under-5 mortality rate has reduced substantially from 1990 in all states, but there was a 4-fold difference in this rate between the highest in Assam and Uttar Pradesh as compared with the lowest in Kerala in 2016, highlighting the vast health inequalities between the states [12].However, the prevalence and spread of illness and diseases at micro level or local level is not known to us and knowing this is very important for ensuring availability and accessibility related to treatment and other healthcare facilities. It is very important to understand things at micro level for having fair intervention at macro level. Hence this study is conducted in urban areas of Aligarh district of Uttar Pradesh in India to study the prevalence pattern of communicable and non-communicable diseases and the prevailing treatment patterns.

2. Conceptual Framework

Illness: According to Cockerham and Ritchey (1997) “by illness we mean a state or condition of suffering as a result of a disease or sickness. In sociology, illness is a subjective state, pertaining to an individual’s psychological awareness of having a disease, symptoms, or pain and typically modifying his or her social behavior as a result or in which individuals perceives themselves as not feeling well and therefore may tend to modify their normal behaviour” [13]. Nettleton (1995) states that illness reminds us that the ‘normal’ functioning of our minds and bodies is central to social interaction. In this respect the study of illness throws light on the nature of interaction between the body, the individual and society. That is, if we cannot rely on our bodies to function ‘normally’, then our interaction with the social world becomes perilous; our dependency on others may become exacerbated and in turn our sense of self may be challenged. Therefore, it is clear that biophysical changes have significant social consequences. It has noted earlier from the literature that responses to illness are not simply determined by either the nature of biophysical symptoms or individual motivations, but rather are shaped and imbued by the social, cultural and ideological context of a person’s biography. Thus, illness is at once both a very personal and a very public or social phenomenon [14].Disease: According to Porta, (2008) “literally ‘disease’ means ‘lack of ease or comfort’, thus underlining the fact that health is characterized by a sense of wellbeing” [15]. Disease is a universal phenomenon. From the functionalist view, it can be said that ‘disease’ is a social fact. It is experienced by all societies, external to the individuals and capable of exerting external constrains on the behaviour of individual. There is no universally accepted definition of ‘disease’ but there have been many attempts to define disease. Webster’s dictionary defines disease as “a condition in which body health is impaired, a departure from the normal state of health, an alteration of the human body interrupting the performance of vital functions” [16]. Bhave, Deodher, Bhave (1975) define disease “as a state which limits life in its power, duration and enjoyment” [17]. “From a sociological point of view disease is considered as a social phenomenon, occurring in all societies and defined and fought in terms of the particular forces prevalent in the society” [18]. Thus, we can say that disease is any deviation from normal functioning of the normal state of complete physical, social and mental wellbeing. Classification of Diseases: Akram (2014) mentioned that in community health, diseases are usually classified as acute or chronic, or as communicable (infectious) and non-communicable (non-infectious) diseases (NCDs) [16]. Communicable (Infectious) Diseases: The communicable (infectious) diseases can spread from person to person directly or indirectly through air, water, direct contact with contaminated surfaces, blood and other bodily fluids, and they are majorly caused by pathogenic microorganisms, such as parasites, bacteria, viruses or fungi. The common cold and COVID-19 are examples of communicable diseases. Mckenzie, et al., (2005) define communicable (infectious) diseases as those for which biological agents or their products are the cause and are transmissible from one individual to another. The disease process begins when the agent is able to lodge and grow within the body of the host [19]. “Of the 9.2 million cases of TB that occur in the world every year, nearly 1.9 million are in India accounting for one-fifth of the global TB cases. Experts estimate that about 2.5 million persons have HIV infection in India, world's third highest. More than 1.5 million persons are infected with Malaria every year. Diseases such as dengue and chikungunya have emerged in different parts of India, and a population of over 300 million is at risk of getting acute encephalitis syndrome/Japanese encephalitis. One-third of global cases infected with filaria live in India. Nearly half of leprosy cases detected in the world in 2008 were contributed by India. More than 300 million episodes of acute diarrhea occur every year in India in children younger than 5 years of age” [20]. Non-communicable (Non-infectious) Diseases: Non-communicable (non-infectious) conditions and diseases are second only to communicable diseases in terms of their contribution to the disease burden in India. These conditions include cardiovascular diseases, cancers, diabetes, respiratory diseases, and mental health diseases. Non-communicable diseases characterized by slow progression but long duration. In fact, non-communicable (non-infectious) diseases are those that cannot be transmitted from an infected person to another, healthy one [16].Non-communicable diseases are one of the major challenges for public health in the 21st century, not only in terms of human suffering they cause but also the harm they inflict on the socioeconomic development of the country. According to WHO projections, the total annual number of deaths from NCDS will increase to 55 million by 2030, if timely interventions are not done for prevention and control of NCDs. In India, nearly 5.8 million people (WHO report, 2015) die from NCDs (heart and lung diseases, stroke, cancer and diabetes) every year or in other words 1 in 4 Indians has a risk of dying from an NCD before they reach the age of 70 [21].Illness Behavior: Akram (2014) states that Illness behaviour is an important variable in medical sociology because not everyone responds the same way when sick. Some people go to physicians for treatment when they experience symptoms of illness, while others with the same symptoms may attempt self-care or dismiss the symptoms as not needing attention. Some people may even deny the experience of symptoms out of anxiety for what the symptoms may mean (e.g., AIDS, cancer). Subjective interpretations of feeling states when ill are the basis of illness behaviour. Models of illness behaviour have been developed by Parsons in his well-known concept of the sick role [16].Determinants of Health: Akram (2014), in his book ‘Sociology of Health’ explain the core determinants which influence the health and well being of the human beings.1) Education: Low education levels are linked with poor health, more stress and lower self-confidence. Health education and awareness builds people’s knowledge, skills, and positive attitudes about health. 2) Physical environment: Safe water and clean air, healthy workplaces, safe houses, communities and roads all contribute to good health. 3) Employment and working conditions: People in employment are healthier, particularly those who have more control over their working conditions.4) Social support networks: Greater support from families, friends and communities is linked to better health. Culture - customs and traditions, and the beliefs of the family and community all affect health.5) Genetics: Inheritance plays a part in determining lifespan, healthiness and the likelihood of developing certain illnesses. Personal behaviour and coping skills – balanced eating, keeping active, smoking, drinking, and how we deal with life’s stresses and challenges all affect health.6) Health service: Both access to health services and the quality of health services can impact health. Barriers to accessing health services include lack of availability, high cost, lack of insurance coverage and limited language access. These barriers to accessing health services lead to unmet health needs, delays in receiving appropriate care, inability to get preventive services as well as hospitalizations that could have been prevented.7) Age and gender: Men and women have different health requirements at different stages. Hence, age and gender are also important health determinants.8) Income and social status: Higher income and social status are often linked to better health. The greater the gap between the richest and poorest people, the greater the differences in health. Poverty creates serious handicaps in the path of good health.9) Lifestyle: Lifestyle is increasingly being considered as an important determinant of health. Diseases such as obesity or diabetes are also related to food habits and lifestyle. They are also depended on level of physical activity maintained in the changing lifestyles patterns. Smoking or consumption of tobacco is a cause of cancer in various parts of the world.10) Biological agents: Biological organisms such as bacteria and virus play the role of carrier of infection. Such factors prevail under specific conditions. Prevalence level of such factors also play important role in ensuring health conditions of population.11) Basic health goods: Food, nutrition, potable water, and sanitation are the foundation stone of health and can be categorized as basic health goods (BHGs). Availability, accessibility, and affordability of these BHGs are important for having good health in the society [16].India has a large burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases. There is a need for effective treatment of diseases and illness conditions for improving life expectancy. It needs to be emphasized that curative treatment (medicinal as well as surgical) is seldom offered without the individual's or community's cognizance of the occurrence of disease through the illness or sickness roles. Globally, different systems of treatment have existed for long. The modern bio-medical system of clinical care has made significant impact on combating the causation and spread of diseases, correcting the complications, and prolonging life. There are other medicine systems grounded in different principles, developed at different periods of time in different parts of world. They are generally known as traditional medicines. In India, medicinal pluralism exists because people have a wide acceptance of different systems of medicine. Among them Ayurvedic, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy are the formally (and also officially) recognized systems of medicine besides the Allopathic system. Further, folk medicines, faith healing, household medicine are also the popular forms of treatment. While medical pluralism gives people the chance to choose which medical system they would like to use, people’s choice is always influenced by several factors. These factors are diverse and work on the collective level as well as on the individual level. A person always has options to choose one amongst different systems depending upon his culture, beliefs, cost, availability, accessibility, type of care expected and various other factors [22].The information made available in the NFHS-4 about the treatment pattern indicate that a higher proportion of household members seek healthcare in the private sector (51.4%) than in the public sector (44.9%) and other source (3.4%) in India. In public sector, there are more users from rural areas (46.4%) than urban areas (42.0%). On the other hand, in private sector, there are more users from urban areas (56.1%) than rural areas (49.0%). Further, in rural areas, 4.5% people seek healthcare from other sources of healthcare and 1.5% urban people seek healthcare from other sources at all India level. Despite progress in improving access to healthcare, there is a huge disparity in access to healthcare in state like Uttar Pradesh. Focusing on urban rural disparity in Uttar Pradesh, we find that in urban area there are more users seeking healthcare from private health sector (71.0%) than from public sector (22.2%). Further, in rural area the higher proportion of household seek healthcare in private sector (66.6%) than in public sector (19.0%) [23]. Treatment Patterns and Health Care System in India: Treatment refers to the interventions made to regain the state of well-being or health from a state of illness and sickness. The formal health care system in India includes multiple systems of medicines including Allopathic, Ayurveda, Homeopathic, Siddha and Unani systems of medicines. Besides these, at informal level, several therapies, remedies and practices also prevail but these informal practices do not become part of the formal healthcare system. The formal health care system is largely divided into the government sector and the private sector and multiple structures and centers exist within each of these two sectors. As explained by Akram (2014), healthcare sector in India is mainly characterized by: (i) a government/public sector that provides publicly financed and managed curative and preventive health services from primary to tertiary level, throughout the country and largely free of cost to the consumer, and (ii) a fee-levying private sector that plays a dominant role in the provision of individual curative care through ambulatory services. The provision of health care by the public sector is a responsibility shared by state, central, and local governments, although it is effectively a state responsibility in terms of service delivery. The health care services organization in the country is extended from the national level to village level [16].Government Funded HealthcareAkram, (2014) says that the government funded healthcare service organization in India extends from the national level to the village level:1) National and State levelsAt the national level the health system is regulated by Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. At the state level the organization is under the State Department of Health and Family Welfare in each state, headed by a Minister and with a Secretariat under the charge of Secretary/Commissioner (Health and Family welfare) belonging to the cadre of Indian Administrative Service.2) Regional and district levelsIn the states of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and others, zonal or regional or divisional set-ups have been created between the State Directorate of Health Services and District Health Administration. Each regional/'zonal set-up covers three to five districts and acts under authority delegated by the State Directorate of Health Services.3) Sub-divisional/taluka levelAt the taluka level, healthcare services are rendered through the office of Assistant District Health and Family Welfare Officer (ADHO). The ADHO is assisted by Medical Officers of Health, Lady Medical Officers, and Medical Officers of General Hospital. These hospitals are gradually being converted into Community Health Centers (CHCs). Home Remedy: Webster’s dictionary defines home remedy as a medicine made with ingredients available at home. Indian home remedies, prepared with the vast variety of herbs, spices and other vegetation available in India, not only help to cure diseases but also to prevent them. These remedies are generally supposed to strengthen the body's mechanisms to fight diseases. This is perhaps the strongest point in favor of home remedies [24]. Besides these, very often, people use the specific Allopathic/ Ayurvedic/ Unani medicines without any medical supervision or prescription which is certainly an ill-practice. Similarly, quacks or unqualified persons also very often prescribe medicine and this is also an ill-practice.

3. Objectives and Methodology

The aim of this paper is to find out the illness and treatment patterns among urban people. This study is conducted in selected wards of Aligarh city of Uttar Pradesh, India. In Aligarh city, there are 70 wards and we have selected two wards (Indra Nagar Khor Road and Malkhan Nagar) by using multi-stage random sampling. Enquiries about the health conditions of the family members were made from every household in the selected wards and households which reported prevalence of any illness were included for the study. One member from one participating household was included for the study. The primary data is collected from 300 respondents from the selected wards by using Interview Schedule. The respondents were asked to name the disease that they suffered from within last one year and the treatment method that they followed. The diseases are self-reported and no enquiry was made to check the medical or hospital certifications for the identification of the disease or the treatment. The respondents were told about the academic purpose of the data collection and data was collected from only those respondents who agreed to willingly provide the information. The names and personal identity of the respondents are not revealed in this research.

4. Findings

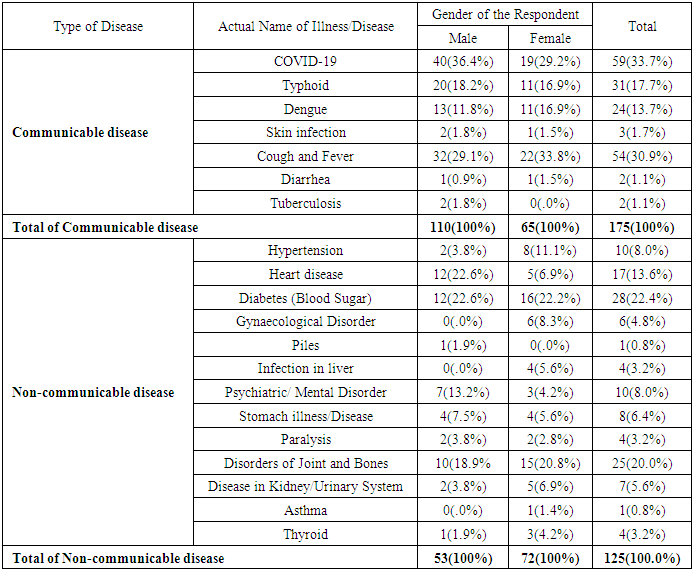

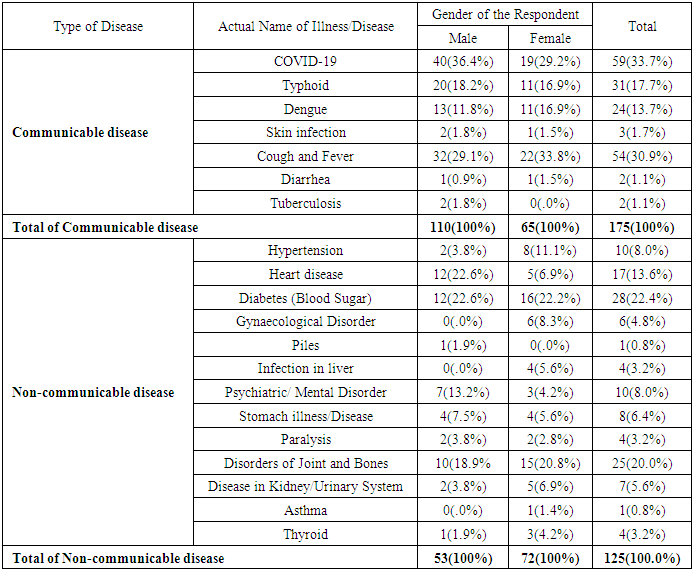

The respondents were asked to name the disease that has affected them the most in last one year. Some of the respondents suffered from multiple diseases and in such situations, the disease affecting them the most was recorded for the study. The type of disease is classified as communicable or non-communicable diseases. Under the category of communicable diseases, COVID-19, Typhoid, Dengue, Skin infection, Cough and Fever, Diarrhea, Tuberculosis are prevailing in the study area. Under the category of non-communicable diseases, Heart disease, Diabetes (Blood Sugar), Disorders of Joint and Bones, Psychiatric/Mental Disorder, Stomach illness/Disease, Hypertension, Infection in liver, Paralysis, Disease in Kidney/Urinary System, Gynaecological Disorder, Piles, Asthma, Thyroid are prevailing in the study area.

4.1. Gender and Type of Illness/Disease

Table 1 shows that prevalence of communicable diseases (58.3%) is more than non- communicable (41.7%) among the respondents. In terms of gender, Table-1 shows that the prevalence of communicable disease among the male respondents is more than the female respondents in the study area. Further, higher proportions of male respondents are suffering from COVID-19 where as in case of female respondents, higher proportion are suffering from Cough and Fever disease. Many among these cough and fever cases could be undiagnosed COVID-19 also but these females are not aware of it as they didn’t undertake any of the COVID-19 tests. Under the category of non-communicable disease, the high proportion of respondents are female who suffers from non-communicable diseases. Further, as visible in Table-1, the percentage of respondents suffering from Diabetes (Blood Sugar) is same among male and female in the study area. Table-1 also provides detailed prevalence of other communicable and non-communicable diseases among both the gender. It has been observed during field work that most of the neighborhoods of the study areas have open drainage system, water logging and dumping of wastes and other similar problems which play important role in spread of diseases. Very often, people are not wearing mask for protecting themselves from COVID-19.Table 1. Cross Tabulation of Actual Illness, Gender of the Respondent and Type of Disease

|

| |

|

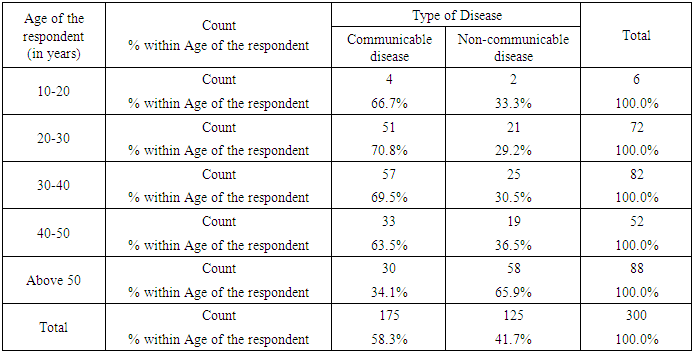

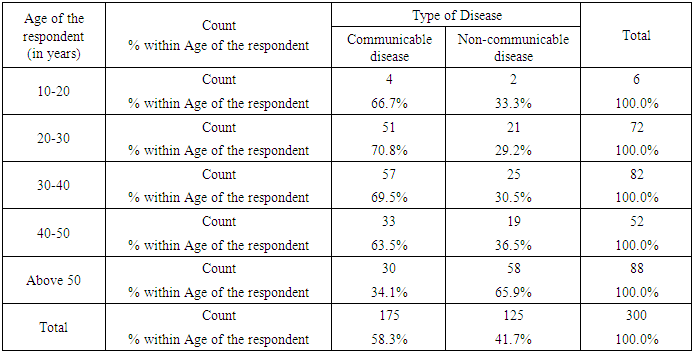

4.2. Age and Type of Illness/Disease

In this study, age group is divided into five categories: (i) 10-20 years (N=6); (ii) 20-30 years (N=72); (iii) 30-40 years (N=82) (iv) 40-50 years (N=52); and (v) above 50 years (N=8). Table 2 reveals that out of the respondents from age group 10-20, 66.7% suffer from communicable disease and 33.3% suffer from non-communicable disease in the study area. Out of 72 respondents from age group 20-30, 70.8% suffer from communicable disease and 29.2% suffer from non-communicable disease. Out of 82 respondents from age group 30-40, 69.5% suffer from communicable disease and 30.5% suffers from non-communicable disease. Out of 52 respondents from age group 40-50, 63.5% suffer from communicable disease and 36.5% suffer from non-communicable disease. Out of 88 respondents from age group ‘Above 50’, 34.1% suffer from communicable disease and 65.9% suffer from non-communicable disease in the study area.Table 2. Cross Tabulation of Age of the Respondent and Type of Disease

|

| |

|

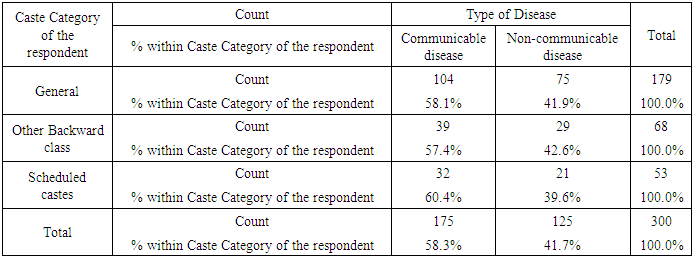

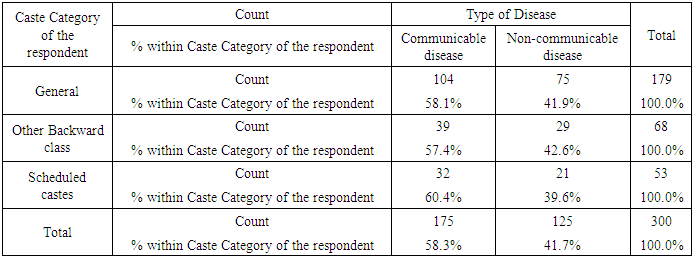

4.3. Caste Category and Type of Illness/Disease

Table 3 shows that out of 179 respondents who belong to General Castes, 58.1% suffer from communicable disease and 41.9% suffer from non-communicable disease in the study area. Out of 68 respondents who belong to Other Backward Classes (OBCs), 57.4% suffer from communicable disease 42.6% and suffer from non-communicable disease in the study area. As visible in Table-3, out of 53 respondents who belong to Scheduled Castes (SCs), the higher proportions of respondents (60.4%) suffer from communicable diseases. It has been observed during field work that in the locality of the Scheduled Castes (SCs) population, they have open drainage system, water logging and dumping of wastes are common problems. Fogging is never done or done very rarely to prevent diseases caused by harmful bacteria and there is foul smell and lot of mosquitoes in the locality.Table 3. Cross Tabulation of Caste Category of the Respondent and Type of Disease

|

| |

|

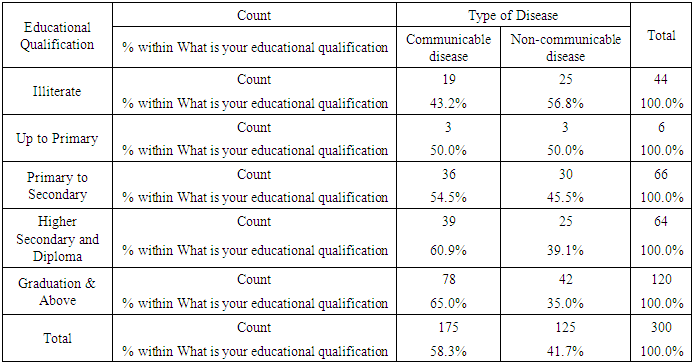

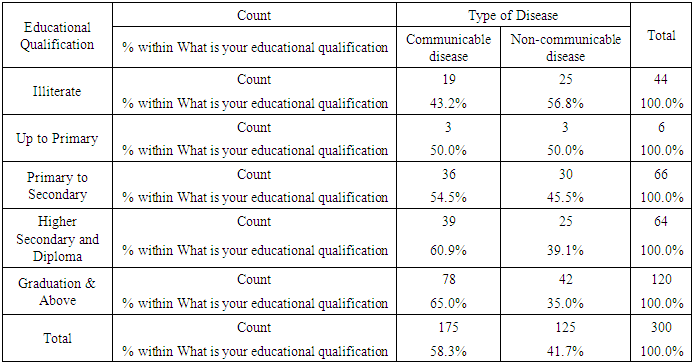

4.4. Educational Qualification and Type of Illness / Disease

Table 4 reveals that out of 44 illiterate respondents, 43.2% suffer from communicable disease 56.8% suffer from non-communicable disease in the study area. Out of 66 respondents educated between primary to secondary levels, 54.5% suffer from communicable disease 45.5% suffer from non-communicable disease. Out of 64 respondents educated at Higher Secondary and Diploma levels, 60.9% suffer from communicable disease and 39.1% suffer from non-communicable disease. Out of 120 respondents educated at Graduation & above levels, 65.0% suffer from communicable disease and 35.0% suffer from non-communicable disease.Table 4. Cross Tabulation of Educational Qualification and Type of Disease

|

| |

|

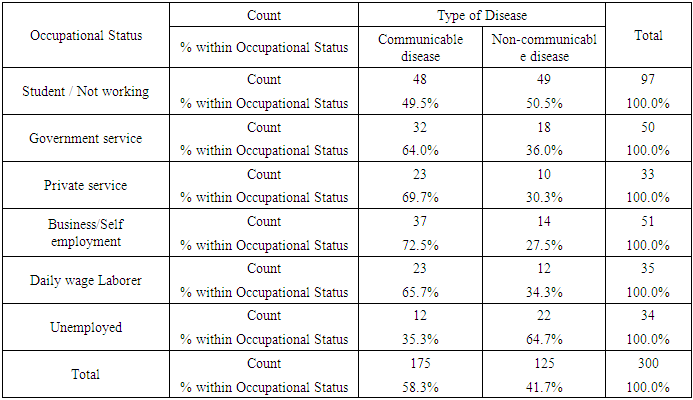

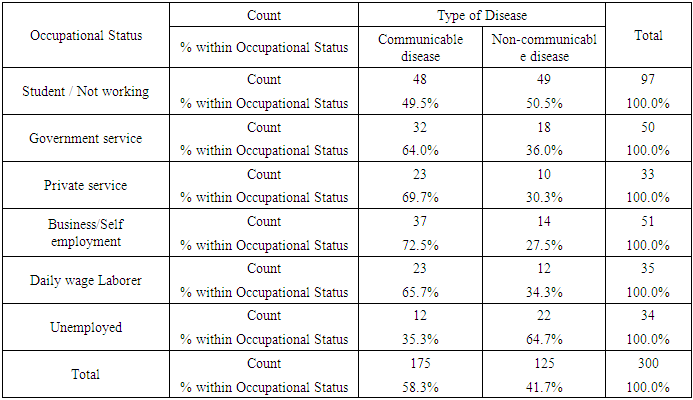

4.5. Occupational Status and Type of Illness/Disease

Table 5 reveals that out of 97 student or non-working respondents, 49.5% suffer from communicable disease and 50.5% suffer from non-communicable disease in the study area. Out of 50 government service respondents, the higher proportion of respondents suffered from communicable disease (64.0%). Similar is the case of private service respondents (33); the higher proportion of respondents suffer from communicable disease (69.7%). Out of 51 business/self-employment respondents, 72.5% suffer from communicable disease and 27.5% suffer from non-communicable disease in the study area. Out of 35 daily wage laborer respondents, 65.7% suffer from communicable disease and 34.3% suffer from non-communicable disease in the study area. Out of 34 unemployed respondents, 35.3% suffer from communicable disease and 64.7% suffer from non-communicable disease. As this study was conducted when COVID-19 had spread, that’s why many of the respondents of every field of occupation were suffering from communicable disease.Table 5. Cross Tabulation of Occupational Status and Type of Disease

|

| |

|

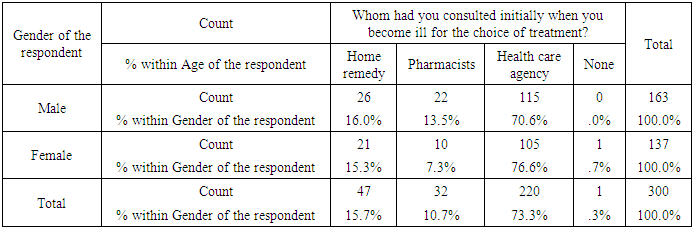

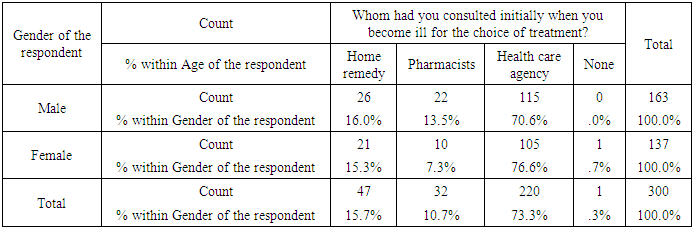

4.6. Gender and Treatment Pattern

Researchers have classified the category of treatment on the basis of the answers of the respondents to the question, “Whom did they consult initially for the choice of treatment when they become ill?” and there are three types of responses provided by the respondents: i) Home remedy; ii) Medicines purchased directly from the Pharmacists; iii) Health care agency; and iv) None. Table 6 reveals that out of 163 male respondents, 70.6% had consulted health care agency, 16.0% had taken home remedy, and 13.5% had consulted pharmacist. Similarly, out of 137 female respondents, 76.6% had consulted health care agency, 15.3% had taken home remedy, 7.3% had consulted pharmacist and 0.7% had neither consulted anyone nor took any remedy.Table 6. Cross Tabulation of Gender of the Respondent and Initial Choice of Treatment

|

| |

|

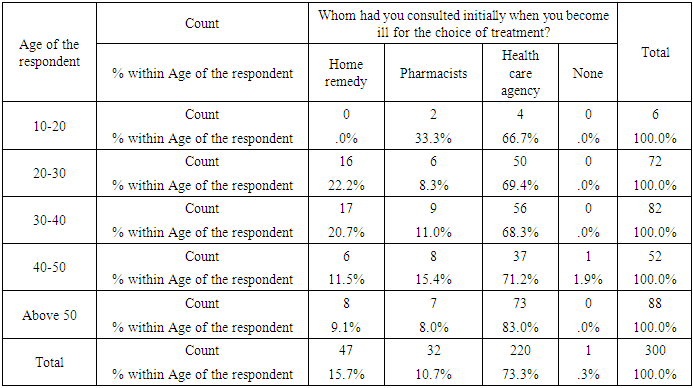

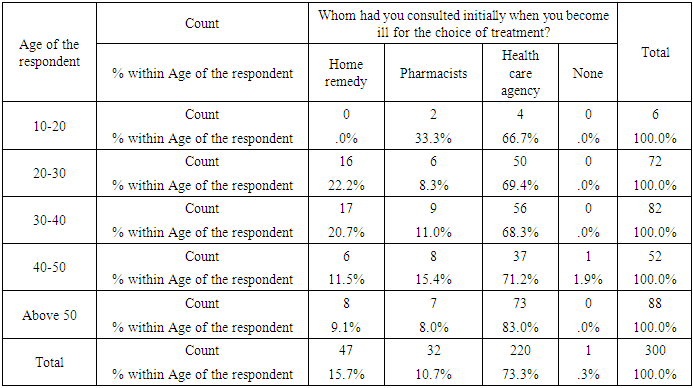

4.7. Age and Treatment Pattern

Out of 6 respondents from age group 10-20, 66.7% said that they had consulted to the health care agency and the rest of the respondents had consulted to the pharmacist. Out of 72 respondents from age group 20-30, 69.4% said that they had consulted to the health care agency 22.2% had taken home remedy and the rest of the respondents had consulted to the pharmacists. Out of 82 respondents from age group 30-40, 68.3% said that they had consulted to the health care agency and 20.7% had taken home remedy and the rest of the respondents had consulted to the pharmacists. Out of 52 respondents from age group 40-50, 71.2% said that they had consulted to the health care agency, 15.4% had consulted to the pharmacists, 11.5% had taken home remedy and the rest of the respondents (1.9%) had neither consulted anyone nor took any remedy. Out of 88 respondents from age group ‘Above 50’, 83.0% said that they had consulted to the health care agency, 9.1% had taken home remedy and the rest of the respondents had consulted to the pharmacists.Table 7. Cross Tabulation Age of the Respondent and Initial Choice of Treatment

|

| |

|

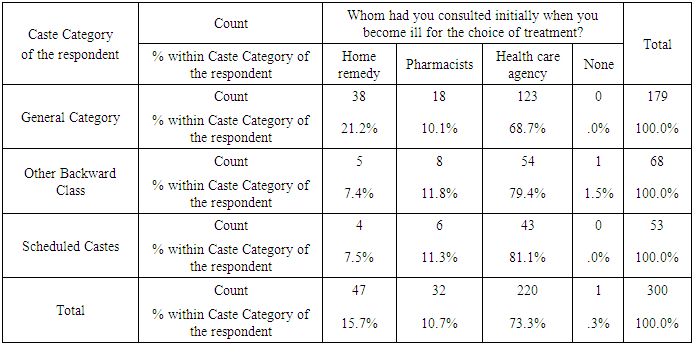

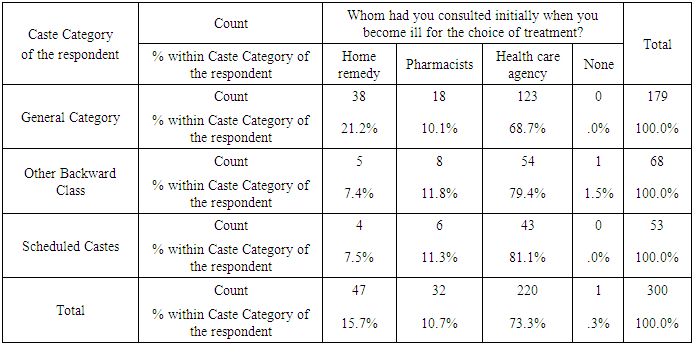

4.8. Caste Category and Treatment Pattern

Table 8 shows that out of 179 respondents who belong to General Castes, 68.7% said that they had consulted to the health care agency, 21.2% had taken home remedy, and 10.1% had consulted to the pharmacists. Out of 68 respondents who belong to Other Backward Classes (OBCs), 79.4% said that they had consulted to the health care agency, 11.8% had consulted to the pharmacists, 7.4% had taken home remedy and the rest 1.5% had neither consulted anyone nor took any remedy. Out of 53 respondents who belonged to Scheduled Castes (SCs) 81.1% said that they had consulted to the health care agency, 11.3% had consulted to the pharmacists and 7.5% had taken home remedy.Table 8. Cross Tabulation of Caste Category of the Respondent and Initial Choice of Treatment

|

| |

|

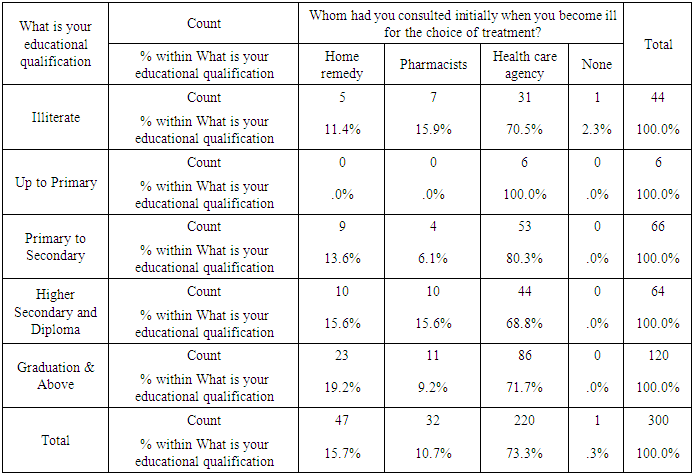

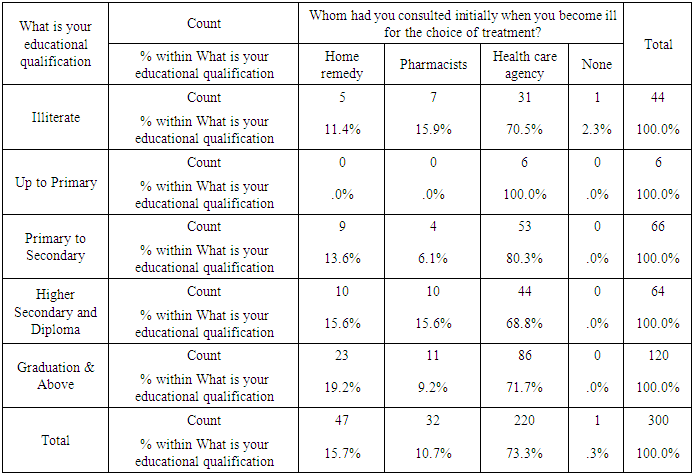

4.9. Educational Qualification and Treatment Pattern

As visible from the Table-9, out of 44 illiterate respondents, the higher proportion of respondents said that they had consulted to the health care agency (70.5%), 15.9% had consulted to the pharmacists,11.4% had taken home remedy and the rest 2.3% had neither consulted anyone nor took any remedy. Out of 6 respondents educated up to primary, 100% said that they had consulted to the health care agency. Out of 66 respondents educated between primary to secondary levels, 80.3% said that they had consulted to the health care agency, 13.6% had taken home remedy and 6.1% had consulted to the pharmacists. Out of 64 respondents educated at higher secondary and diploma levels, the higher proportional of respondents said that they had consulted to the health care agency (68.8%) followed by pharmacists (15.6%) and home remedy (15.6%). Out of 120 respondents educated at graduation & above levels, the higher proportion of the respondents said that they had consulted to the health care agency (71.7%) followed by home remedy (19.2%) and pharmacists (9.2%).Table 9. Cross Tabulation of Educational Qualification and Initial Choice of Treatment

|

| |

|

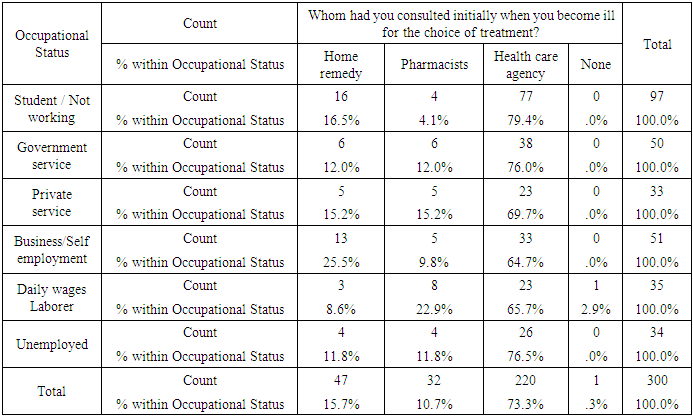

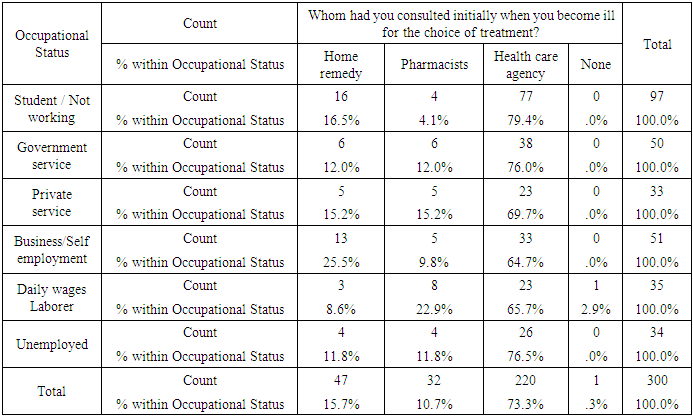

4.10. Occupational Status and Treatment Pattern

As visible from Table-10, out of 97 student / non-working respondents, the higher proportion of respondents said that they had consulted to the health care agency (79.4%) followed by home remedy (16.5%) and pharmacists (4.1%). Out of 50 government service respondents, 76.0% said that they had consulted to the health care agency and the rest of the respondents had taken treatment from pharmacists and home remedy. Out of 33 private service respondents, 69.7% said that they had consulted to the health care agency and the rest of the respondents had taken treatment from pharmacists (15.2%) and home remedy (15.2%). Out of 51 business/self-employment respondents, 64.7% said that they had consulted to the health care agency, 23.5% had taken home remedy and 9.8% had consulted to the pharmacists. Out of 35 daily wages laborer respondents, 65.7% said that they had consulted to the health care agency, 22.9% had consulted to the pharmacists, 8.6% had taken home remedy and the rest 2.9% had neither consulted anyone nor took any remedy. Out of 34 unemployed respondents, 76.5% said that they had consulted to the health care agency and the rest of the respondents had taken treatment from pharmacists (11.8%) and home remedy (11.8%).Table 10. Cross Tabulation of Occupational Status and Initial Choice of Treatment

|

| |

|

5. Conclusions

India has a large burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases. There is a need for effective treatment of diseases and illness conditions for improving life expectancy and quality of life. As we have seen that United Nations General Assembly has also prioritized health and well-being of individuals and for the promotion of the same it has suggested several core steps. Health is one of the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals put forth by the UN general assembly in its agenda 2030 and it has laid stress on the health and well-being of all.Moreover, non-communicable diseases are the biggest hurdles and challenge for sustainable development. The NCDs take heavy toll all over the world. NCDs are one of the major challenges for public health in the 21st century not only in terms of human suffering they cause but also the harm they inflict on the socioeconomic development of the country. Communicable diseases pose a serious threat to individuals’ health and have the potential to threaten collective human security and it has been proven in last two years through the spread of corona virus. Current burdens of communicable diseases make them a continuing threat to public health in all countries. India must orient the health system towards prevention, screening, early intervention and new treatment modalities with the aim to reduce the burden of communicable as well as non- communicable disease.

References

| [1] | United Nations. (2016). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from http://u6.gg/k5dp3. |

| [2] | World Health Organization. (2021). Non-communicable diseases. Retrieved January 15, 2022, fromhttps://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases. |

| [3] | Roser, M., Ritchie, H. (2016). Burden of Disease. Our World in Data. Retrieved January 20, 2022, from https://ourworldindata.org/burden-of-disease. |

| [4] | Bonita, R., Beaglehole, R., Kjellström, T. (2006). Basic Epidemiology (2nd ed.) Geneva: WHO. |

| [5] | World Health Organization. (2021). Factsheets. Retrieved January 15, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets. |

| [6] | World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19). Retrieved January 15, 2022, from https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1. |

| [7] | World Health Organization. (2022). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. With Vaccination Data. Retrieved January 25, 2022, from https://covid19.who.int/. |

| [8] | India. (2019). Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved January 15, 2022, from https://artsandculture.google.com/entity/india/m03rk0?hl=en. |

| [9] | Kopf, D., Varathan, P. (2017). If Uttar Pradesh were a country. Quartz. Retrieved October 25, 2021, from http://u6.gg/k5dsd. |

| [10] | Census of India. (2011). Uttar Pradesh Population 2011. Retrieved October 25, 2021, from https://www.census2011.co.in/. |

| [11] | Central Bureau of Health Intelligence. (2019). National Health Profile 2019. https://www.cbhidghs.nic.in/showfile.php?lid=1147. |

| [12] | ICMR, PHFI, and IHME. (2017) India: Health of the Nation’s States -The India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative. New Delhi. http://u6.gg/k5ds0. |

| [13] | Cockerham, W.C., and Ritchey, F.J. (1997). Dictionary of Medical Sociology. London: Greenwood Press. |

| [14] | Nettleton, S. (1995). The Sociology o f Health and Illness. UK: Polity Press. |

| [15] | Porta, M. (2008). A Dictionary of Epidemiology (5th Ed.). London: Oxford University Press. |

| [16] | Akram, M. (2014). Sociology o f Health. Jaipur: Rawat Publication. |

| [17] | Bhave, N.V., Deodher, N.S., Bhave, S.V. (1975). You and Your Health. India: National Book Trust. |

| [18] | Park, K. (2019). Preventive and Social Medicine. M.P.: M/s Banarsidas. |

| [19] | Mckenzie, J.F., Pinger, R.R., Kotecki, J.E. (2005). An Introduction to Community Health. London: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. |

| [20] | MOHFW. (2010). Annual Report to the People on Health, Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family welfare, September 2010, p.14. |

| [21] | National health portal of India. (2021). Non- communicable diseases. Retrieved October 25, 2021, from https://www.nhp.gov.in/healthlyliving/ncd2019. |

| [22] | Akram, M. (2017). Disease, Illness and Health Care: A Sociological Conceptualization of the Indian Experience. In S. Dixit., A.K. Sharma (Eds.), Psyco-social Aspect of Health and Illness (127-159). Concept Publishers, New Delhi. |

| [23] | National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) 2015-16: Report India and 29 states- (2017) Government of India- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Mumbai International Institute for Population Sciences. |

| [24] | Health Indian recipes. (2022). Retrieved from 18 February 2022. https://www.tarladalal.com/recipes-for-home-remedies-371. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML