-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Sociology

p-ISSN: 2169-9704 e-ISSN: 2169-9739

2022; 12(1): 9-18

doi:10.5923/j.ijas.20221201.02

Received: Sep. 25, 2021; Accepted: Jan. 16, 2022; Published: Jan. 21, 2022

A Qualitative Study of the Effects of Household Income on Students’ Educational Attainment, Interpersonal Relations, and Career Goals and Transition in Korea

Kim Se Jeong

Osaka University, Japan

Correspondence to: Kim Se Jeong , Osaka University, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This qualitative research explored the effects of household income levels on college students’ academic discontinuation (educational attainment), relationship-building propensity, and employment (career goals and transition). In-depth interviews were used to collect data from student participants at four-year colleges, particularly third- and fourth-year undergraduate students, who have been in college for an extended time period, and expect to graduate soon and enter the workforce. The participants were then divided into two groups: Group I included students from high income households, whose full tuition and living expenses have been paid, while Group II comprise students from low income households with outstanding fees. These interviews were analyzed based on the key themes of academic, human relations, and employment. The experiences college students from high income households and those from low income households are extremely at variance, showing that students’ economic levels affect their interpersonal relationships and future career prospects. Household income is found to influence the level of awareness of their career prospects and values. Conversely, low income students do not think of academics as an independent domain of “study,” despite recognizing it as a requirement. Consistent with this finding, these two groups of students also demonstrate different consumption patterns and capacity to establish human relations, with those in the high-income group at a greater advantage then their low-income counterparts. Overall, the level of income inequality, as established in this research, has significant effects on college students’ educational attainment levels, interpersonal relationship, and employment, whereby favourable effects are appropriated to high income students.

Keywords: Income polarization, Income and education, College graduate employment, Classical sociological theory, Economic determinism

Cite this paper: Kim Se Jeong , A Qualitative Study of the Effects of Household Income on Students’ Educational Attainment, Interpersonal Relations, and Career Goals and Transition in Korea, International Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. 12 No. 1, 2022, pp. 9-18. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20221201.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Prior to graduation and entry into the labour market, threats of unemployment and underemployment remain among the most direct and urgent realities that many college students in Korea have to contend with. Across the research, there is an increased appreciation of the idea that college education enables college students to identify universities and careers, and that it has lost its original purpose of educating undergraduates (Korea Educational Development Institute, 2008; The Adult and Continuing Education of Korea, 2004). Despite this reality, the percentage of high-school graduates entering a college reached a peak of 83.8% in 2008, followed by a yet high rate of >70% (Korea Educational Development Institute, 2008). These high college enrolment rates indicate the reality surrounding how multiple college students will soon be troubled by the limitations of youth unemployment. Against this backdrop, there is significant rationale for this study to explore the effects of household income levels on college students’ academic discontinuation (educational attainment), relationship-building propensity, and employment (career goals and transition).

2. Materials and Methods

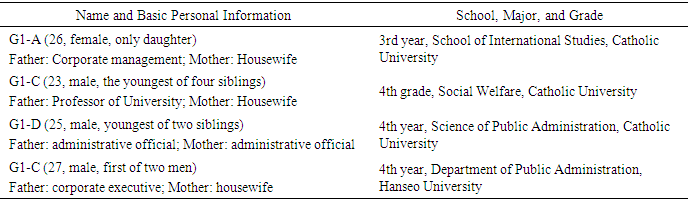

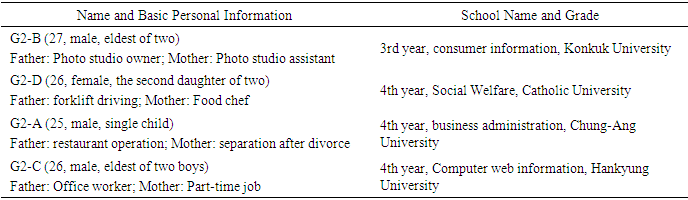

- A qualitative research method was used in this research, whereby data was collected using in-depth interviews. Study participants included students currently enrolled at four-year colleges, particularly third- and fourth-year undergraduate students who have been in college for an extended time period, and are on the verge of graduation and entering the workforce. There were no restrictions on the participants’ university and gender. However, the age limit was set at 22–29 years, which is a period in which students experience college life. Students also tend to be most involved in the preparation for employment. The participants were split into two groups: Group I and Group II. Group I (4 people) comprised students whose families cover full tuition and living expenses, while Group II (4 people) included students who cover their own economic conditions rather than receiving complete tuition and living expenses from their families. Participants in Group I were coded as G1-A, G1-B, G1-C and G1-D. Those in Group II were coded as G2-A, G2-B, G2-3 and G2-4. Responses from the two groups were then compared and analyzed on the basis of their background and current experiences. The participants’ theoretical background and current state were also compared against findings from a review of existing studies. The period of the research cycles was from September 2018 to March 2019. The rationale for using in-depth interviews was to collect data in an open and interactive format, which were then coded based on themes that the interviewees and interviewer intend to address. In-depth interviews were, therefore, divided into a series of questions and themes that directly reflection the objectives of this research. This is made it possible to probe the interviewees for clarification and to discover meanings that the researcher could not directly observe regarding the background of income polarization, and how household income levels are affecting college students’ educational attainment and career prospects. In the “Study” item related to university life, three categories were examined: consciousness and values, academic status, and non-university studies. In “Human Relations” item, three categories, consumption, leisure, and friendship, were examined to find out how economic background works. Finally, in the “employment” item, two categories, consciousness and values and readiness for employment, were explored. A comparative analysis of the differences between these two groups was then performed. The information on interviewees for the two groups is shown in the table 1 and 2 below.

|

|

3. Results

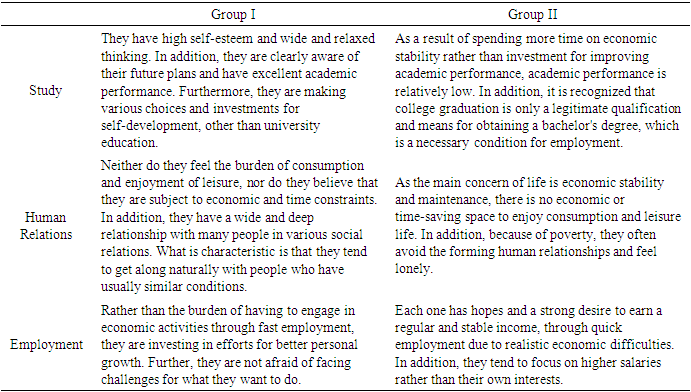

- Based on thematic analysis of participants’ responses, eight key themes emerged that reveal that students’ economic levels affect their interpersonal relationships and future career prospects. These include (i.) awareness and values; (ii.) academic status; (iii.) non-university higher education; (iv.) consumption patterns and human relations; (v.) leisure activities; (vi.) awareness and values of employment; (vii.) formation of friendships and other interpersonal relationships; and (viii.) readiness for life after graduation.Theme 1: Awareness and valuesThe theme of awareness and values emerged from the participants’ responses. Responses from students in Group I seemed to agree that household income influences the level of awareness of career prospects and values. G1-A, and G1-C seemed to agree that students need to have the freedom to select what to study. However, this should be conditioned by a sufficient level of awareness and recognition of value.“College is where you can achieve what you want to do. Rather than focusing on economics, I think it is important to do what you really want to do by sticking to your studies and investing in a lot of things.” G1-A, Catholic University“I did a transfer but I did not worry even when I heard that I could not get a GPA scholarship. I thought it was natural to select what I really wanted to do rather than a scholarship, and I heard that my parents would pay the school tuition.” G1-C, Catholic University“It is good to study at school but you only have to study somewhat. Traveling abroad, taking a leave of absence, and having various experiences are the most important things in college life. After getting a job, I cannot afford it anymore; therefore, I think it is important to do many things in the most important time.” G1-C, Hanseo UniversityBuilding on G1-A, and G1-C’s perspectives, it is construed that college life forms the basis for which students can do what they want to do, develop a strong sense of awareness and appreciation of their value. Furthermore, it is observed that it is important to focus on academic work in college life, appreciate diverse college experiences, and invest time and effort for value recognition.When it comes to participants in Group II, there appears to be a general sense of awareness of the value of education. G2-B and G2-C also seem to share the perspective that students may find it unable to focus on their studies because they have to cover their tuition and living expenses.“I should have good grades to obtain a good job. I have difficulty studying for classes after I have to do a part-time job on weekdays and weekends.” G2-B, KonKuk University“Rather than studying, you meet only a certain level of grade that your company wants. I think I cannot do well, although I want to do well. I am really tired of working every day.” G2-C, Hankyung UniversityHwang and Kim are clearly concerned about the importance of academics. Another possible inference is that students in Group II do not think of academics as an independent domain of “study;” despite recognizing it as a requirement. Rather than having a sense of what it means to study, they think of it as a tool for career advancement.Theme 2: Academic StatusA comparative analysis of some of the student participants in Group I reveal a high level of concentration and sincerity toward studying. G1-A and G1-C demonstrate a general attempt by students to adequately prepare for classes. “I have an average grade of 4.3. I am almost never late and I am very enthusiastic about studying, so I have to work hard on exams and assignments. Because I do not have a part-time job, I can spend more time focusing on studying.” G1-A, Catholic University“I always concentrate hard in class. I tend to actively participate in presentations and assignments in class, and I do actively participate in group assignments. You cannot neglect schoolwork, so you should do your best to study. I do not think my grades are low either; my grade is between 3.8 and 3.9.” G1-C, Hanseo UniversityG1-A and G1-C’s responses clear shoe that students in Group I have a high ‘achievement desire’ for academics. Indeed, an examination of the overall grade point average, which is the most thorough indication of academic status, it was found that three out of four interviewees were close to 4.0 (4.5 points). This indicates that students in Group I have a good academic standing and a high desire for achievement.For Group II, each student seems to focus on maintaining their academic performance. In spite of this strong indication, it is also open from G2-B, G2-A, and G2-D’s points of view that students in this group do not have considerable time to invest in it owing to their part-time jobs.“By nature, I do not neglect my studies and I am always working hard on homework, exams, and attendance. However, because I have to work part-time on weekdays and weekends, I usually doze off in class and lose the chance of taking notes. This is an excuse but I only have a GPA of 3.4.” G2-B, KonKuk University“I do not have much enthusiasm for studying but there is a GPA requirement for employment. Therefore, I manage to spare hours to study hard, and my GPA is ~3.8. I work at the school on weekdays until 11 PM and on weekends from 11 AM to 5 PM; however, I think it is not bad for me to work part-time all week.” G2-A, Chung-Ang University“I could not properly study because I have to work hard to earn tuition. Every day, I was dozing off in class and I could not attend school because I was sleeping, and I did not obtain a good grade because I sent a rough assignment. I have a grade of 3.4 now; however, I am a little worried because classmates said the GPA must be >3.5 to get a job.” G2-C, Hankyung UniversityAs observed, G2-B, G2-A, and G2-D provide perspectives that demonstrate that in many cases, because of the cumulative fatigue owing to working part-time and lack of proper concentration in class or absence and lateness, the degree of dedication and participation in class is not generally high. Apparently, students in Group II demonstrate a strong understanding that criteria for maintaining academic grades should be aligned with level required by the company at the time of employment. They occupy a score of about mid-to-late 3 (i.e., 4.5 grade points).Theme 3: Non-University Higher EducationAll four interviewees in Group I showed a strong dedication to off-campus studies. Areas of interest included patent attorney preparation, pharmacy vocational examination (PEET) preparation, hospice training, education for civil service exams, and education for financial certification. Of the students in this group, G1-A from Catholic University provided a compelling perspective on non-university higher education trends, where students are motivated to pursue extra qualification. Le said that since he aims to go to graduate school, he has invested a lot in English. He also constantly visits TEPS academy. He explained that he has learnt that because he was high school student, there was nothing more to learn at the academy. Since he aspires to study in the United States, he enrolled in English language training course. He said:“I learnt that because I was a high school student, there was nothing more to learn at the academy. I had a chance to go to school in the United States before I entered elementary school, and I went to a language training course; therefore, I have not had much difficulty studying English.” G1-A, Catholic UniversityG1-C from Hanseo University also observed the significance of extra qualifications. He said:“To graduate from college, I require English test scores; if I am not good at English these days, I obtain little attention. I am still regularly taking the TOEIC test, and I am studying English by going to both academy and library. Most importantly, I think it is important to practice English after learning English; therefore, I travelled a lot to an English-speaking country such as the USA or Singapore for a month or two during vacation. Certainly, when I go to a local area, I have multiple experiences and increase my confidence in English. Since I think I want to work in the financial sector, I am steadily studying using online courses while studying financial certifications such as investment counsellors and AFPK.” G1-C, Hanseo UniversityOverall, students in Group I showed a strong dedication to off-campus studies. As found, they have obtained other necessary qualifications (TEPS, TOEIC). They also have multiple experiences of overseas language study or travelling to English-speaking countries, which is one of the methods to improve English proficiency.On the other hand, students in Group II do not show a strong dedication to off-campus studies. When it comes to self-development, only one of the four interviewees attended an English conversation course. G2-C said:“I do visit an English academy like everyone else, and I want to learn everything as a hobby. However, there are times these activities feel like a luxury because I have to pay for student loans and earn living expenses. I have no time for doing other things. Nevertheless, everyone usually goes to the English academy and I need to study English for employment… Now I am sincerely thinking about how this can be done.” G2-C, Hankyung UniversityConversely, G2-B and G2-A expressed that their part time work made it difficult for them to pursue off-campus studies. They said:“I have a part-time job outside of school; therefore, I do not have much time for me yet. I want to go out and learn sports, but I usually spend all my time on doing assignments, sleeping, and watching TV. Thus, I have no time to learn something.” G2-B, KonKuk University“Because of part-time work, it is hard to spend time learning other things, in addition to school classes; I am too busy every day just by taking classes at school and doing assignments from professors.” G2-A, Chung-Ang UniversityAs observed, regarding participants in Group II, it is considered that while some interviewees are interesting in learning diverse things off-campus to boost their qualifications, they have limited time to do so because of part-time jobs. When they have the time, they still have to complete school assignments and unfinished work during that time. For those in Group II, who seem to have no time or have the economic affordability to identify time, one important aspect to note and consider is the expression “luxury,” as mentioned by Kim.Theme 4: Consumption Patterns and Human RelationsSome participants drawn from Group I provided perspectives that demonstrate a likely relationship between students’ consumption patterns and capacity to develop human relations. As evident below, G1-A and G1-C reveal that spending on artefacts or activities that encourage social relations is common among some students.“I usually meet my friends once a week to play around; however, I think I always spend a lot by providing treats. I love buying food and coffee for people I really like. Moreover, I have a major interest in sneakers, so much so that I buy a pair whenever my favourite brand releases a new model. I think it is similar to how others buy a new luxury bag.” G1-A, Catholic University“I spend a lot of money on school buses because my school is a little far from my home. Usually, I spend a lot of money when I meet my girlfriend. I think it is not a waste for me to invest in a person I like. Moreover, I spend a lot of money on my girlfriend anyway because I strongly believe that a man has to pay on a date.” G1-C, Hanseo UniversityIn Group I, certain consumptions determine the type of social relationships that students pursue. In particular, they demonstrate strong patterns of consumption, such as buying something for their favourite person or spending on leisure to invest in relationships. Thus, this group is characterised by a strong drive to invest in strong personal relationships.On the other hand, students in Group II were found to have comparatively little time and economic wherewithal to spend their money on building interpersonal relationship. Instead, they prioritise their tuition and living expenses, as G2-B, G1-A and Park explained.“I had lunch with my close friends at university; sometimes, I had a drink with them but they worked a part-time job. I think it is a burden to drink and play. If you eat something, you end up spending >20,000 won, which is not a small amount of money. Even without a part-time job, I can obtain the basic necessities of life. Moreover, even when I had a girlfriend, we broke up because I was busy all day and could not afford things and because I felt that my girlfriend had certain dissatisfaction. I did not want to hold on to her because I did not have sufficient time or money. I feel alone leaving her like that… However, I cannot help it in this situation.” G2-B, KonKuk University“You might use the term “consumption;” however, you do not have time to do it and you cannot afford it. Honestly, I want to buy something I want to have, I want to meet my friends and play with them. However, I cannot do that; it is true that I feel lonely. It is burdensome to spend on myself. I am just not satisfied with this situation.” G1-A, Catholic University“On an average, the expense of maintaining a relationship a month is not much. Most of the money goes toward paying living expenses and school fees. Usually, I do a part-time job after school; therefore, I cannot hang out with people.” G2-A, Chung-Ang UniversityHence, the differences in students’ consumption patterns reveal that investment in activities that encourage building of human relations tends to be difficult for students in Group II owing to their more limited financial ability. Despite this, they desire to do so, and as made out from Kim’s response, students in Group II do feel lonely, particularly when they find it difficult getting along certain people.Theme 5: Leisure activitiesThe theme of leisure activities also emerged from the coded data. As deduced from G1-A and G1-C’s responses, participants in Group I seem to be more obliged to participate in leisure activities.“Let us say leisure time. Nowadays, I spend a lot of time working out and studying with my girlfriend; therefore, we are watching movies, eating, and sometimes going to refresh our minds. Previously, I used to travel or steadily go to the fitness centre.” G1-A, Catholic University“I do not seem to have any spare time, and I spend a lot of time meeting my friends, drinking, playing, or spending time with my girlfriend. Both me and my girlfriend like to see and experience a lot of places; therefore, I always plan on weekends and holidays, and I often go near or far away to play together.” G1-C, Hanseo UniversityFrom Kim and Lee’s statements, it is plausible to argue that the most striking feature of Group I is that each student often spends their free time with friends or lovers who can share something they enjoy. As discussed in the “Consumption” section of Group I, people can have improved relationships by leisure with friends and lovers.A different perspective is provided by students in Group II. Because of financial constraints, their leisure activities is not characterised with much spectacle. G1-A and G2-A revealed that they restrain their leisure activities to simple acts of inexpensive leisure or voluntary activities.“I usually do not have a lot of free time. When I do, I perform volunteer work and social welfare practice a lot during vacation. I want to graduate anyway; therefore, I try to go there many times to gain considerable experience. If you have considerable experience or perform many activities, it will be more advantageous for you.” G1-A, Catholic University“I have a limited amount of time; therefore, sometimes I just meet my friends and eat or drink. There are multiple things I want to do with my friends; however, there is a lot of pressure to do something different or stop doing things right away. So, I do not think it is going to be easier.” G2-A, Chung-Ang University“I want to have spare time. I do not have sufficient time to sleep; therefore, it is hard to have free time. I usually sleep a lot at home alone when I have time. I do not have much to say about leisure except regularly meeting with friends for a drink.” G2-C, Hankyung UniversityIn Group II, rather than enjoying a special leisurely life, focus is placed on participating in volunteer activities that would be helpful for securing a job, sometimes meeting with friends, or resting. Primarily, in this leisure time, some students seem to spend their time by themselves. Because they were unable to go somewhere to do a special leisure activity, they had certain difficulties in expanding their relationships with their friends. When linked back to the theme of “Consumption” discussed earlier, it can be interpreted that there is a risk of potential isolation owing to inadequate leisure and consumption.Theme 6: Formation of friendships and other interpersonal relationshipsThe theme of friendship also emerged across data drawn from some interviews with students in Group I and Group II. G2-A and G1-C’s statements offer some evidence showing that those in Group I tend to be more conscious of “us” with their friends. They are also portrayed as more amiable to friends of similar levels and values, particularly when talking about the economic and social levels of their families.“I have been dating many people in college, thus attending various meetings and that is what personally bothers me. I think I am more inclined to meet my friends in middle and high school than my college friends. Moreover, everybody has an ambition to be big later, and they have a lot of experience because they are very motivate.” G1-A, Catholic University“I like my college friends and I often meet and talk with my friends from my high school. They are so funny and thoughtful friends; therefore, it is easy to talk to them and everybody knows what they want to do. There are many friends who say that the other friends I met in college are not deep, and there are multiple college people who are as close as my high school friends are. I think it is best to have those people who can just share something together.” G1-C, Hanseo UniversityGenerally, interviewees drawn from Group I tend to be more conscious of “us” when associating with their friends. They also prefer associating with friends of similar income levels and values, particularly as they tend to talk about the economic and social levels of their families. In any case, they are interested in keeping meaningful and good relationships with their friends.On the other hand, some students in Group II reveal that they do not tend to feel a sense of belonging. G1-A and G2-A revealed that as much as they lack a sense of belonging, they seek to strengthen their sense of belonging.“Because of my busy life, I have no choice but to neglect dating, friends, and meetings. Everybody wants to have a meaningful relationship, but I do not think I have sufficient time to socialize. However, I used to be in touch with some of my friends who I met in college, get along well, and get a lot of comfort. Nevertheless now, all of them have graduated, so I have no people to share my worries to and no one to comfort me, and so I am feeling lonely.” G1-A, Catholic University“I often participate in school events, and I want to get along with people. However, I do not have time to do that because of my part-time job every day. So, when I see friends who participate well in school and play well with friends, I always wonder, ‘Do you not have a part-time job?’ I feel separated from the group and I want to belong.” G2-A, Chung-Ang UniversityClearly, some students in Group II do not feel a sense of belonging. While some of these students wish to participate in school activities and meetings and make more friends, they are unable to do so because of their part-time jobs and financial and time constraints. For college students who have a large economic burden, their difficulties may lead to problems in forming and maintaining human relations macroscopically and friendships microscopically. This construed from the frequency of statements drawn from their interview scripts, such as “I feel lonely,” “I do not belong,” and “I feel separated from the group, lonely, and stuffy.”Theme 7: Awareness and Values of EmploymentThe theme of awareness and values of employment also emerged from the coded interview scripts. Particularly notable was the discovery that some students in Group I stated that their consciousness and value formation about their employment were significant shaped by their parents.“My father was a professor at a university; both my parents wanted me to continue studying. Because I was young, I had a strong desire to continue studying while watching my father; therefore, now I am aiming to enter the Graduate School of Psychology, Seoul National University, even if it takes some time. Money is money but I think it is the biggest advantage that I can live while studying.” G1-A, Catholic University“My father was a company executive; therefore, I had many opportunities to meet people in the financial sector. I think it would be fun and if I manage my network well, I would be able to enter multiple fields. My father told me that if I study toward the financial sector, he can introduce me to many things and people, and the more I study, the more fun it would be.” G1-C, Hanseo UniversityFrom G1-C’s and G1-C’s statements, it is ascertained that their consciousness and value formation about their employment was primarily influenced by their parents, particularly their fathers. Each of the four interviewees preferred to enter professions such as pharmacists, professors, civil servants, and financial workers. They raised more questions about what they really wanted to do rather than the economic conditions of identifying a job. Moreover, they were willing to do what they wanted to do even if it took long. This could indicate that students from higher income households are more likely to have similar occupations or professional occupations depending on their parents’ shared values to employment.Unlike a majority of the students in Group I, those in Group II want to identify a job by themselves that they feel will enable them to attain a more stable economic and social life. G2-B, G2-A, and G2-C provide perspectives that lead to this conclusion.“The reason for obtaining a job is that everybody is attempting to make money. Therefore, I want to get a high salary. I want to work at a place where my starting salary is more than ~27 million won; even if I do not want it, I think I will prefer the salary first. Once I get a job, I will be able to stably and leisurely earn money and plan for the future in the long run.” G2-B, KonKuk University“I want to get a job fast and make money; therefore, I can have a more stable life than now. Thus, I never thought I wanted to get the job I wanted to do and I did not really want to do it; therefore, I was just focusing on economics. Anyway, I have to quickly get a job; however, it is frustrating to see myself without time by doing a part-time every day. Therefore, these days, when I see those people who live at home with a lot of support, I think, ‘If I got all that support, I could do better’.” G2-A, Chung-Ang University“I want to get a job at a high-salary company. I took a leave of absence to earn money and rode on things such as a fishing boat; however, it was so hard that I felt overwhelmed. I have not considered what I want to do when I go to school; therefore, I want to work for a company with a high salary. Because my major is the computer field, I want to work for a company related to my major. Anyway, I have heard that if you have skills, you can get a good job.” G2-C, Hankyung UniversityIn Group II, therefore, there was a strong tendency to consider the most important part of employment, primarily economics. Most of the interviewees in this group wanted to identify a job and achieve a more stable and an economically better life. The economic conditions are, apparently, the most decisive factor in the consciousness and values of employment in Group II. The primary cause of forming such consciousness and values is the family’s low-income level.Theme 8: Readiness for life after graduationThe theme of readiness or preparedness for life after graduation manifested dominantly from the participants’ interviews. As G1-A and G1-C stated, some students in Group I demonstrate a high level of preparedness for life after graduation, and seem to be more assured of getting a job or proceeding with their education.“I am focusing on studies in my major steadily to enter graduate school, and I require a good TEPS score to enter Graduate School at Seoul National University. I think it is a good idea to study harder until you graduate so that you can obtain more grades. During my Master’s and Doctoral Programs, my parents told me that they would support me. So, I will try my best to receive the letter of acceptance to the Graduate School.” G1-A, Catholic University“I have been studying English all along and I have got certain GPA; therefore, I am going to focus on the financial certification exams. To date, I have acquired about three certifications; therefore, I am going to study further and apply to the bank or securities companies whenever I get a job posting.” G1-C, Hanseo UniversityThe readiness for employment among students in Group I was reported to stabilize. All students in this group were observed to be proficient in speaking English, and had made an effort to acquire relevant certificates applicable to their future career fields. It is conceivable from their data that most students have relatively modest economic burdens, and demonstrate greater readiness to invest time and money in their academic performance and future preparation.Conversely, some students in Group II demonstrate a lower level of preparedness for life after graduation, and seem to be less assured of getting a job or proceeding with their education. G2-B, G2-D, and G2-C attested to this.“I have been studying for TOEIC on my own using certain workbooks because it seems to be important; however, I cannot concentrate on it much because I have been too busy with my life, thus earning money through part-time jobs. In my senior year, I would like to take fewer classes; therefore, I can focus more on studying English. It seems that I am not prepared for obtaining a job after graduation.” G2-B, KonKuk University“It seems that I have not done anything to prepare for employment after college to date. I have been attempting to do it in the spare time after doing my part-time job; however, I could not do it because I tend to get tired. Therefore, I have no idea what type of job I would get after graduation…I just managed to get decent grades.” G2-D, Joongang University“I have not done anything to prepare for employment after graduation. I do not have English test scores either… I should get a computer-related certificate before I graduate; therefore, I can add a line in my resume. Since I am a senior now, I should think seriously about it.” G2-C, Hankyung UniversityIn Group II, therefore, most students were unsure about preparing for employment after graduation. They also lack of practical preparation for employment, as they are less disposed to acquire official English test scores and relevant certificates. This is clearly attributed to financial constraints and preoccupation with their part-time work. In fact, some of them do not seem to have specific employment goals post-graduation. The results revealed are summarized table 3 below.

|

4. Discussion

- The study met its objectives of examining the background of income polarization and how household income levels affect college students’ educational attainment levels, interpersonal relationship, and employment. Results (See table 3) show that students’ economic levels affect their interpersonal relationships and future career prospects. This is a clear indicator that the expansion and strengthening of neo-liberalism and revision capitalism strengthen economic deterministic inequality. In a way, this is extremely important as it demonstrates that economic conditions already exert considerable influence on various human relationships. Consistent with this finding, many studies based on classical theory have demonstrated that material or economic conditions have considerable effects on institutions, laws, and ideas, as cam be explained by Marx and Engels’s economic determinism and materialism (Marx, 2010; Comninel, 2019) and Althusser’s theory of reproduction (Althusser, 1955). A comparative analysis of respondents in student Group I (high income students) and student Group II (low income students) demonstrate that their experiences are extremely at variance. Household income is found to influence the level of awareness of their career prospects and values. They view college life as forming the basis for develop a strong sense of awareness and appreciation of their value. Conversely, low income students do not think of academics as an independent domain of “study,” despite recognizing it as a requirement. Rather than having a sense of what it means to study, they think of it as a tool for career advancement. At any rate, it becomes apparent that low income students want to identify a job and achieve a more stable and an economically better life. High income students are also found to demonstrate a high level of concentration and dedication to studying, and a general attempt by students to adequately prepare for classes. This is in contrast to low income students, who demonstrate that in many cases, because of the cumulative fatigue owing to working part-time and lack of proper concentration in class or absence and lateness, the degree of dedication and participation in class is not generally high. Results for consumption patterns and human relations also reveal differing results among high income and low income students. Those in the high income group demonstrate a likely relationship between students’ consumption patterns and capacity to develop human relations, such as leisure activities. They spend on artefacts or activities that encourage social relations is common among some students. On the other hand, those in the low income group are found to have comparatively little time and economic wherewithal to spend their money on building interpersonal relationship. Hence, they are less likely to invest in activities that encourage building of human relations, including leisure activities. Yet, this also influences their capacities to develop friendships and other interpersonal relationships. While high income students can invest in leisure activities to create and sustain friendships and other interpersonal relationships, those in the low income group do not. This may also imply greater readiness for life after graduation. Indeed, the results suggest, high income students demonstrate a high level of preparedness for life after graduation, and seem to be more assured of getting a job or proceeding with their education than low income students.Nevertheless, depending on students’ economic conditions, unequal life makes it difficult to attain career aspirations and goals through college education. Bowles and Gintis’s (2011) theory states that inequality is primarily reproduced in elementary, middle, and high school curricula. It is, therefore, inferred from participants’ responses that inequality has already permeated the university curriculum. The level of income inequality, as established in this research, has significant effects on college students’ educational attainment levels, interpersonal relationship, and employment, whereby favourable effects are appropriated to high income students (Byun, Kim, and Kang, 2020). In the same context, the results in this study highlight the significance of improving Korea’s education system to ensure a greater sense of equality to prevent personal and social anxieties, which contributed to high level of stress and depression among low income students (Chae, 2020). Indeed, findings in this study suggest that low income students lack a sense of belonging while in college, which could expose them to such stresses.Parents are also found to influence the career goals and values of high income students than those of low income students. This is consistent with earlier findings by Billari and Kohler (2004), which showed that economic base and class of parents directly affect the formation of children’s assets and that young people in economically wealthy families tend to be positive and active about love, marriage, and parenting. This is a strong indicator that the economic conditions of parents significantly determine the economic conditions of their children. Besides, their economic power (capital strength) has a profound influence on the setting of personal relationships such as love, marriage, parenting, and future life directions (Oshio et al., 2011). This could indicate that students from higher income households are more likely to have similar occupations or professional occupations depending on their parents’ shared values to employment.

5. Conclusions

- The experiences college students from high income households and those from low income households are extremely at variance, showing that students’ economic levels affect their interpersonal relationships and future career prospects. Household income is found to influence the level of awareness of their career prospects and values. Conversely, low income students do not think of academics as an independent domain of “study,” despite recognizing it as a requirement. Hence, because of being saved from the burden of economic constraints, the degree of dedication and participation in class among the high-income students is expected to be higher, although it can also be affected by their greater disposition to engage in leisure activities may affect their performance. Consistent with this finding, these two groups of students also demonstrate different consumption patterns and capacity to establish human relations, with those in the high-income group at a greater advantage then their low-income counterparts. As evidenced, high income students spend on artefacts or interactive activities that enable them to create wider interpersonal relationships. There is also an indication of greater readiness for life after graduation among high income students because of their investment in Non-university higher education qualifications. Parents are also found to influence the career goals and values of high-income students than those of low-income students. This is a strong pointer that the economic conditions of parents significantly determine the economic conditions of their children. Overall, the level of income inequality, as established in this research, has significant effects on college students’ educational attainment levels, interpersonal relationship, and employment, whereby favourable effects are appropriated to high income students.

6. Recommendations

- A variety of recommendations are made to mitigate the effects of economic polarization and how household income levels affect college students' educational attainment, interpersonal relationship, and employment.Guarantee free universal education• Establish methods to achieve free, equitable, and high-quality primary and secondary education from pre-primary to secondary levels by providing universal, fee-free early childhood classrooms to secondary levels.• Eliminate all costs, including informal payments, with the goal of ultimately achieving fee-free secondary education. This must be carefully developed so that quality is not jeopardized. Increase access to the necessary one first year fee-free, good pre-primary education gradually. • Provide more assistance to the poorest and minorities in order to reverse economic disadvantages in schools and keep them in school and learning.Concentrate on policies that may help deliver quality for everyone.• Create a fully costed and funded strategy to create a skilled, competent, and most well professional workforce, provided with sufficient teachers and other staff to educate everyone through secondary school.• Use appropriate assessments to generate a feedback loop for curriculum planning and classroom changes at the local level. Focus should not be placed on simply associating higher test results with higher quality.Establish more egalitarian educational systems• Create public education plans that focus rationally and comprehensively on detecting pre-existing educational disparities, giving data regarding gaps and needs, and executing proper solutions.• Guarantee equitable teacher placement, as well as equitable investment in educational facilities and learning materials, to help rectify disadvantage. Affirmative action may be required in impoverished or more disadvantaged areas or regions.• Ensure greater investment in proven means of remedying inequality for disadvantaged or underprivileged children.Fully fund public education systems in order to achieve quality and equity for everyone.• Government spending must aggressively address inequality, particularly by employing equity-of-funding measures to ameliorate the historical disadvantage faced by the poorest communities.• Invest in the development of robust mechanisms for effective monitoring and transparency of education expenditures at all levels, from the school to the local to the national.

7. Research Implications

- The results in this study highlight the significance of improving Korea’s education system to ensure a greater sense of equality to prevent personal and social anxieties, which contributed to high level of stress and depression among low income students. Indeed, findings in this study suggest that low income students lack a sense of belonging while in college, which could expose them to such stress and depression. The results offer insight into how a sense of inequality exists in the education system. Addressing them could reduce stresses and depression among students. Findings also suggest how students’ level of preparedness for life after graduation, and prospects for job and career prospects can be improved.

8. Research Limitations and Future Research

- This study had some underlying limitations. Because of the limited sample size used in this research, future studies are necessary as the results of this study are not automatically generalizable to a broader population. Future researches should consider using larger study sample and longitudinal research design in Korea to examine the long-term the effects of household income levels on college students’ academic discontinuation (educational attainment), relationship-building propensity, and employment.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML