-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Sociology

p-ISSN: 2169-9704 e-ISSN: 2169-9739

2022; 12(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.ijas.20221201.01

Received: Dec. 16, 2021; Accepted: Dec. 31, 2021; Published: Jan. 13, 2022

Maternal Health in India During Covid-19: Major Issues and Challenges

Tehzeeb Anis, Mohammad Akram

Department of Sociology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India

Correspondence to: Tehzeeb Anis, Department of Sociology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The covid-19 pandemic situations have shown us that healthcare systems in several countries including India, in order to prevent the spread of covid-19 infection and control other related situations, neglected many other healthcare services including reproductive and maternal health services during the lockdowns imposed to prevent the spread of covid-19 and even afterwards. But this negligence cannot be justified, as maternal health services are one of the most important factors for the well-being of the mothers as well as the children. The disruption in access to maternal healthcare and antenatal care, including routine check-ups, sonography tests, scans, institutional deliveries, postnatal check-ups, vaccination of children, etc., has led to increased suffering of pregnant women and this situation will ultimately lead to compromised maternal and child healthcare. The aim of this paper is to review the major issues and challenges pregnant women face in accessing maternal health services during covid-19 period. This is an analytical paper based upon secondary data and estimates made in several published papers and media reports. Data provided by National Family Health Survey-4 (NFHS-4) (2015-16) is used as baseline data in this paper and findings of several reports and articles on related topics have been reviewed and used to arrive at some conclusions. On the basis of available reports, a projection is made on the estimated fall in antenatal care, institutional deliveries, and postpartum services. According to some estimates, antenatal care has dropped by 20 to 30 percent, institutional delivery by 30 to 43.25 percent and postnatal care by 20 to 30 percent during and after the lockdown caused because of the ongoing pandemic. During the pandemic, the number of labor and delivery at home increased as well. With the rise in labor and delivery at home, the risk of improper deliveries has increased, resulting in possibility of more premature mortality of the mothers and newborns. Around 25-30 percent fall is estimated in the doses of common vaccines given to children which is a serious matter of concern. The covid-19 pandemic has taught us that health preparedness should always be ready to deal with such a kind of pandemic without effecting the other healthcare services.

Keywords: Maternal health, Antenatal care, Institutional deliveries, Postnatal care, Vaccination

Cite this paper: Tehzeeb Anis, Mohammad Akram, Maternal Health in India During Covid-19: Major Issues and Challenges, International Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. 12 No. 1, 2022, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20221201.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Maternal health refers to the healthcare of women during pregnancy, childbirth, and postnatal period. Application of appropriate maternal healthcare measures like antenatal care (ANC), institutional delivery, and post-partum care of mother and child prevent maternal and child mortality and other related complications. Almost all developed and developing countries have made maternal health a higher priority, allocating more resources to antenatal care and promoting institutional deliveries; as a result, maternal deaths worldwide have decreased by nearly half (44%) since 1990, and use of maternity services has increased significantly [1]. Despite this fact, around 295,000 women died globally during childbirth and postpartum period in 2017 according to a World Health Organization (WHO) report [2]. Further, approximately 94 percent of deaths occurred in low-resource settings, and most could have been prevented [2]. In one of the recent studies, a ‘‘three- delay’’ model has been used to identify the causes of the decrease in utilization of maternal health services during covid 19 [3]. The concept of three delays include: delaying the decision to seek health care, delaying arrival at a healthcare facility, and delaying receiving needed care [4]. The recent covid-19 pandemic has impacted almost every aspect of life, including maternal health services. In this covid-19 pandemic, the ‘three delays’ as elaborated in the three-delay model, have played an important role in not getting proper maternal health services.The ongoing coronavirus pandemic has challenged each and every aspect of the healthcare systems of the world and has forced almost all countries in the world to go into complete shutdown [5]. The ongoing pandemic has created obstacles in the services provided by healthcare facilities [6]. Due to this coronavirus pandemic, healthcare workers, equipment, and healthcare facilities have been transformed into covid hospitals to cope with the rising numbers of infected people [7], leaving little space for the healthcare of pregnant women. Pregnant women have been affected by disarrayed routine health services, especially in low-income and middle-income countries like India [7].The government of India ordered the first complete nationwide lockdown from March 25, 2020, for 21 days, limiting the movement of millions of people in order to prevent the spread of covid-19 transmission. The second phase of lockdown started on April 15, 2020, and continued for 19 days. The third and fourth phases started on May 4, 2020 and May 18, 2020 respectively, and both continued for 14 days each. After the fourth phase of lockdown, the unlocking phases started, in which partial movement was allowed with certain guidelines. The first phase of unlocking was started on June 1, 2020, and it continued for 30 days. Since then, the unlocking phase started in the form of unlock 2, 3, and so on. The complete restrictions imposed on movement during the lockdown have created obstacles in reaching health care facilities. The lockdown created restrictions on even proper antenatal care and postpartum care or with minimum utilization of maternal health services. The strict implication of lockdown raised serious concerns about ensuring safe, timely and quality maternal health care in both rural and urban areas. The discontinuation of antenatal care and barriers to reaching institutional facilities for delivery care created a major problem for pregnant women. The disruption in access to maternal healthcare and antenatal care, including routine check- ups, sonography tests, scans, institutional deliveries, postnatal checkups, vaccinations of children, etc., has led to increased suffering of pregnant women, ultimately leading to an increased possibility of high maternal and child mortality rates. The Indian healthcare system allocated the majority of its resources, including emergency services and intensive care unit beds, to serve the covid-19 patients or keep them reserved for them. In fact, many private hospitals were also turned into covid hospitals leaving almost nothing or very low proportion of services for the care of other sick and ill people including pregnant women. The aim of this paper is to review the major issues and challenges pregnant women face in accessing maternal health services during covid-19.

2. Methodology

- The impact of covid-19 on maternal healthcare services in India is estimated in this article by extrapolating the estimates made in many published papers and media reports and the baseline data for the various prevalence rates are taken from the National Family Health Survey-4 report (2015-16) [8]. National Family Health Survey (NFHS) is a pan India survey conducted periodically to provide the baseline health related data in India. In NFHS-4, a total of 628,900 households were selected for the sample, of which 616,346 were occupied, and of which 601,509 were successfully interviewed. A total of 699,686 women aged 15-49 were interviewed [8]. NFHS-4 data has been used as a baseline data in this paper because it is highly reliable and gives data on health indicators at both state and national level. Academic papers and various reports produced on maternal health services during covid-19 have been reviewed and used for the estimations and extrapolations in this paper. We have used the various estimates provided in different newspapers for calculating the fall in maternal healthcare services and institutional deliveries because no official statistics on these is available. The projected figures were calculated on the basis of the averages and estimates as provided in four major newspapers in India viz. The Hindustan Times [9], New Indian Express [10], The Economic Times [11], and News Click [12].

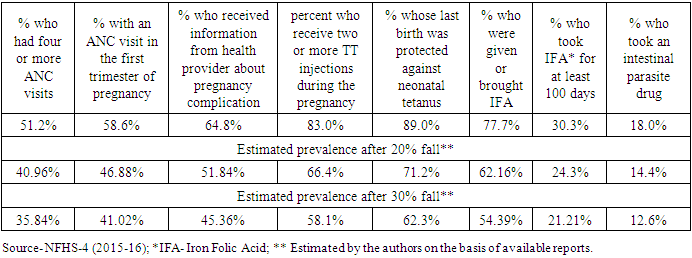

2.1. Delays in Antenatal Care

- Antenatal care (ANC) and related check-ups are one of the most important milestones in pregnancy care. It is very essential for both maternal and fetal health. Consultation with a professional healthcare worker is necessary throughout the pregnancy period as it keeps the pregnant woman informed about the development of the fetus, her own health conditions, and the expected due date of delivery. The ANC visits also help in promoting a healthy lifestyle and help in identifying and treating pre-existing diseases. The WHO has recommended at least four ANC visits, starting with the first before 12 weeks of pregnancy, the second around 26 weeks, the third around 32 weeks, and the fourth between 32 and 38 weeks of gestation. Thereafter, women are advised to return to ANC at 41 weeks of gestation or sooner if they experience any danger signs [13]. The Indian government imposed a nationwide lockdown on March 25, 2020 and maintained it for several weeks. Since then, the women have been struggling with unintended pregnancies and delays in getting antenatal care services. Table 1 gives us information about the percentage and type of antenatal care women received during the pre-covid period and the fall in the services during lockdown.Table 1 shows the different kinds of antenatal care pregnant women usually get during their pregnancy in the pre covid-19 period. It is clear from the table that approximately 51.2 percent women in India followed the recommendation of WHO and got four or more antenatal checkups. Health providers provide information about pregnancy complications to approximately 64.8 percent of women. Approximately 77.7 percent of women were given IFA tablets, which are very important for women during pregnancy. Around 30.3 percent of women took the IFA tablets for 100 days in their pre-covid periods. But the whole scenario has changed since the covid-19 period. As a result, the implication of lockdown created barriers in access to institutional facilities, the suspension of transport facilities, and the non-availability of private and public healthcare facilities have created obstacles in getting ANC services. As a result, pregnant women were not able to get several ANC visits. Women were not able to get iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets either due to restrictions on movement, or unavailability, or limited stocks. In a report published in a national daily, it is mentioned that there has been a fall in ANC registration from 98 percent to 78 percent. In this case, it is important to counsel the pregnant woman on antenatal care [14]. In Lucknow, maternity hospitals were functioning throughout the lockdown period, but the number of expectant mothers coming for follow-up or even delivery in public and private hospitals dipped by around 20 percent. In Rajasthan, where there are about 2,200 primary and community health facilities and 1,100 private hospitals, nearly 150,000 births were registered last year (i.e. 2019), but this figure has fallen by almost half during the period [10].Although the Indian government has not provided any official data on the drop in antenatal care during covid-19, evidence from several newspaper reports suggests that ANC in India has dropped by an average of 20 to 30 percent. On the basis of this evidence, we have formulated an estimate of the fall in ANC during the lockdown period. Table 1 shows the expected prevalence of ANC services after a minimum 20 to 30 percent reduction in services.Table 1 also shows the estimated decrease in antenatal care in India during the lockdown period. It is estimated that only 40.96 percent women had four or more ANC visits. Antenatal care basically includes several checks, scans, tests, etc. Due to strict lockdown implications, most of the private health facilities were closed and public health facilities were converted into covid-19 hospitals. As a result, a sharp decline in antenatal care can be seen in comparison with the previous year’s data. Table 1 also shows that when ANC received a 30 percent decrease, the percentage of women who had four or more ANC visits fell dramatically. Only 35.84 percent of women are estimated to have had four or more ANCs. Further, approximately 45.36 percent of women received two or more Tetanus Toxoid (TT) injections during the pregnancy, while the data was 83 percent during the NFHS-4 survey (2015-16).A sharp decline can also be seen in consumption of iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets, which are recommended by health workers to prevent anemia in pregnant women as well as in the newly born children. Usually, it is advisable to take IFA tablets for 100 days, but due to lockdown, the tablets were either unavailable at pharmacies or people were unable to reach pharmacies or health facilities due to restrictions on movement [15]. The decrease in antenatal care is heading towards a generation where there is a possibility that many children will be born anemic. Many studies claim that antenatal testing and monitoring is important to see if any fetal abnormality is present [16]. If proper screening and monitoring are not done on time, it will be quite difficult for the pregnant women and medical practitioner to understand the growth of the fetus.

|

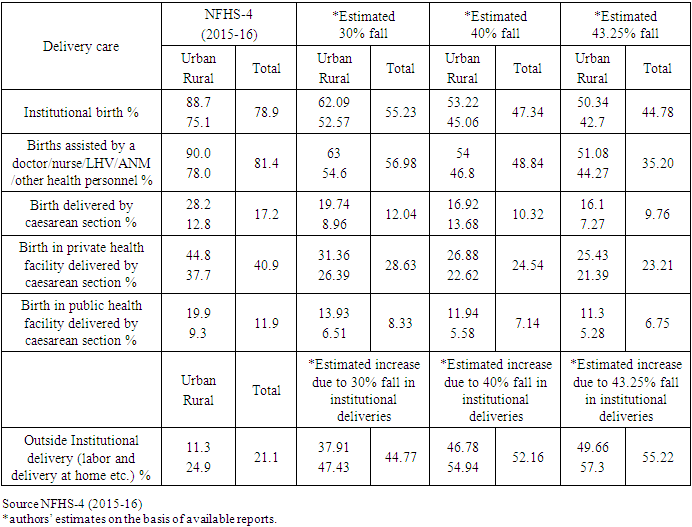

2.2. Place of Delivery and Delay in Reaching the Healthcare Facility

- The place of delivery is one of the most important factors of maternal health services. Before the popularization of institutional delivery, childbirth was considered a private affair, and most childbirths used to take place at home in the presence of traditional birth attendants and some family members. Every day in 2017, approximately 810 women died from pregnancy and childbirth related complications [17]. And this complication can only be prevented if delivery is conducted in the presence of doctors and health professionals at health facility centers. One of the most important factors in reducing maternal and neonatal deaths was institutional delivery. Table 2 shows the kind of delivery care women get both in urban and rural areas before covid-19 and after an estimated fall during the lockdown. Table 2 shows the kind of delivery care women used to get in the pre-covid period as per NFHS-4 (2015-16) data. During the pre-covid period, institutional births predominated at 78.9 percent. According to Table 2, only 21.1 percent of births occur at home during the pre-covid period. Around 17.2 percent of births take place through caesarean section. The most alarming issue in the pre covid period was that almost 40.9 percent of the births in private health facilities were caesarean section [8] crossing the recommendation of WHO that the ideal rate for caesarean sections be between 10 percent and 15 percent [18]. But the pandemic has led to a steady decline in institutional deliveries and access to maternal healthcare. The fear of covid-19 transmission and lockdown restrictions have created barriers to access to institutional deliveries and left many women with giving birth at home as the only option. According to data shared by the Global Financing Facility [19], disruption in services can lead to 4,742,000 women being without access to facilities-based deliveries. As a result of disruptions in all services, child mortality in India could increase by 40 percent and maternal mortality by 52 percent over the next year [19]. Since the lockdown started in March 2020, there have been newspaper reports of pregnant women dying as they were denied access to care. One such report mentions: “A woman in the eighth month of pregnancy died in an ambulance after eight hospitals either referred her to another facility as she showed symptoms of covid-19, or cited a lack of beds” [20]. Another report cited data from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Odisha, and Chhattisgarh states of India claiming that the number of institutional deliveries dropped by up to 40 percent during the lockdown, owing primarily to women giving birth at home [21].Amidst all these negative reports, one significant news that came out was that caesarean section rates have fallen and normal deliveries have gone up [22]. According to a newspaper report, the coronavirus has led to a decrease in the number of caesarean deliveries across the country. Districts like Lucknow, Moradabad, and Agra in Uttar Pradesh have seen the number of caesarean section deliveries drop by two-thirds. The same report claims that since the lockdown started at the end of March 2020 and till June 2020, 360,000 babies have been born in Uttar Pradesh. Usually, the pregnant woman used to opt for a caesarean section, but during covid-19, they have avoided the procedure. The report further claimed that women in Ghaziabad preferred to give birth at home with the help of personal physicians. Several media reports also claimed that there was a sharp decline in institutional deliveries in several states like Bihar, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Odisha, and Chhattisgarh during the lockdown [23]. Various newspaper reports from The Hindustan Times [9], New Indian Express [10], The Economic Times [11], News Click [12] etc. reveal that institutional deliveries in India have been reduced by 40 percent, 43 percent, 50 percent, and 40, percent respectively. On the basis of these reports, the estimated decrease in institutional deliveries during this lockdown period could be calculated as an average of the figures available (40 percent, 43 percent, 50 percent, & 40 percent), and it would be 43.25 percent. However, this fall in services could not be uniform at all places, and hence we have calculated the expected falls at three levels: 30 percent, 40, percent and 43.25 percent. Table 2 gives an estimated idea about the fall in institutional deliveries in both public and private health facilities during the lockdown period.Table 2 shows the estimated institutional birth rate during the lockdown period could have decreased by up to 44.78 percent (with a 43.25 percent fall). Deliveries in both public and private health facilities have been significantly dropped. The biggest drop, however, can be seen in private health facilities, where it has dropped to 17.68 percent during the lockdown. The private health facilities are always on the top of priority list of people because of several factors including its insurance-based healthcare, however, the private health care facilities have seen a drastic fall of around 30-43 percent in institutional deliveries. Private health facilities continued to deliver approximately 40.9 percent of childbirths via caesarean section in previous years, which is cause for concern. But during the lockdown period, caesarean section rates have shown a drastic fall. With the decrease in institutional deliveries, the prevalence rate of deliveries at homes was high during the lockdowns. Around 44.77 percent of women, expectedly, chose to deliver at home, either with the help of some relatives or skilled health personnel or retired auxiliary midwives. Following a 40 percent estimated fall, Table 2 shows that approximately 47.34 percent of women deliver in a hospital, while 52.66 percent deliver at home. During the NFHS-4 survey, only 11.3 percent of births in urban areas occurred at home, whereas during the lockdown, it is estimated that 46.78 percent of births in urban areas occur at home, following a 40 percent drop in institutional delivery. In urban and rural areas, institutional deliveries have decreased in public and private hospitals. In most places, the private health facilities were closed due to the fear of covid-19 transmission, forcing hundreds of thousands of babies to be born outside and unknown to the system.

|

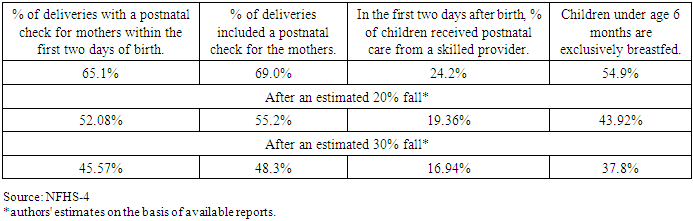

2.3. Delay in Post-Natal Care

- The postnatal period is one of the most critical phases in the lives of mothers and newborn babies. The majority of maternal and infant deaths occur within the first month of birth; nearly half of postnatal maternal deaths occur within the first 24 hours, and 66% occur within the first week [17]. The WHO, in its guidelines, has suggested that postnatal care should be provided within 24 hours to all mothers and babies, regardless of where the birth occurs. If the birth is at home, the first postnatal contact should be as soon as possible, within 24 hours of the birth. At least four postnatal checkups are recommended by WHO [24]. Along with that, mothers should be encouraged to exclusively breastfeed for about the first six months of a baby’s life [24]. Adequate nutrition, iron, and folic acid supplementation are recommended for at least three months post childbirth. Table 3 depicts the types and percentages of postnatal care services provided to pregnant women prior to the covid-19 period, as reported by NHFS-4, and expected to fall during the covid period.According to Table 3, 65.1 percent of mothers received a postnatal check after two days of childbirth during the pre-covid period. Sixty-nine percent of mothers had their deliveries followed by postnatal checkups. Further, 54 percent of children under the age of six months were exclusively breastfed. These figures are from pre-covid times; the figures may drop during lockdown and afterwards. Restriction on movement, suspended transport facilities and fear of transmission of covid-19 infection have created barriers to access to postnatal care. As a result, pregnant woman were unable to get the recommended type of postnatal care. Due to fear of infection, an increased proportion of women preferred to give birth at home and also failed to get postnatal checkups in the first two days after births. During delivery at home, women also faced problems getting advice on breastfeeding, as the auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM) and accredited social health activist (ASHA) were pressed into covid-19 services. Many women could not give colostrum, the first milk, without technical support or handholding by an ANM or nurse on the colostrum feeding procedure. But when women are delivering at home in the absence of an ANM or skilled health provider, the opportunity to feed the child colostrum is lost. Breastfeeding is very essential for the health of the infant, and it also plays an important role in the prevention of sudden infant death syndrome. Because of a lack of skilled health providers and a decrease in institutional births, there is a continuous loss in antenatal care and postnatal care.As all kinds of maternal health care have been impacted by the pandemic, postnatal care has also not been left with this impact. From the media reports, an estimate has been made that postnatal care has also been dropped by 20 percent and 30 percent. Table 3 also shows an average loss in postnatal care during the lockdown period over the NFHS-4 report of 2015-16. With the decrease in antenatal checks, the postnatal checks also went down. New mothers who needed to see a doctor within two days of giving birth were unable to do so due to restrictions on movement or because clinics were closed, resulting in only 52.08 percent of estimated women seeing a doctor within two days of giving birth. Approximately 55.2 percent women had their deliveries with a postnatal checkup. Following a 30 percent drop, the above data shows that only 45.57 percent of women received postnatal checks within two days of delivery, and only 48.3 percent of women had their deliveries with a postnatal check. Postnatal checkups are very important for the mother as well as the child as most of the complications occur either at the time of birth or within 48 hours of birth. With the fall in postnatal care, we can draw an inference that we are moving towards a future where there is an increased possibility of more premature maternal and child mortality. During this lockdown period, more children are likely to remain deprived of vital nutrition, which is provided to them through breastfeeding. As more women are giving birth at home in absence of any health provider or auxiliary nurse midwife, they could not get any proper advice on breastfeeding. NFHS-4 (2015-16) shows that around 54.9 percent children under age 6 months are exclusively breastfed, while the data might have dropped to 43.92 and 37.8 percent respectively in lockdown period. Without a doubt, the lockdown has posed numerous challenges for both new born babies and their mothers.

|

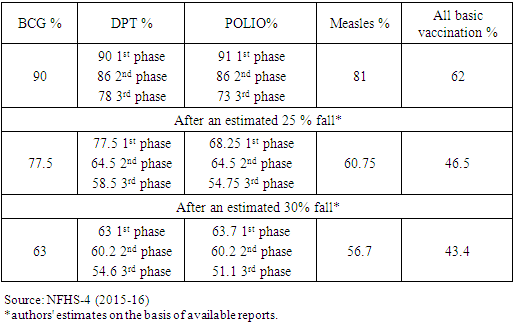

2.4. Immunization of Babies

- Vaccination of children is very important as it protects them from a lot of diseases. The doses of vaccination start as soon as a child is born and are followed till the child reaches the age of two years. Diseases like Diphtheria, Pertussis, Tetanus, Polio, Measles, Tuberculosis, and Hepatitis B as well as Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib) can be prevented by vaccination. The back-to-back lockdown during covid-19 has severely hampered the immunization programme in India. Table 4 shows a comparison of vaccinations given during the years 2015-16 and 2020 or during the lockdown. Three important vaccines which are given at birth are BCG, polio and DPT. Table 4 shows a 25–30 percent decrease in almost every vaccine when compared to NFHS-4 data. Table 4 shows that approximately 90% of children received BCG vaccines in 2015-16 [8]. The first phase of DPT vaccines were also received by 90 percent, while 78 percent received the 3rd phase of the vaccines. In the first phase, 90 percent of the children received polio vaccines. Eighty-one percent received measles vaccines, while 62 percent received all basic vaccinations. But during the lockdown, a huge decline can be seen in the doses of vaccines given to children. On the basis of a report which suggests that around a 25-30 percent fall is seen during the lockdown [12], the authors have estimated data on the fall in immunization. After an estimated 25% fall, only 77.5 percent of children receive BCG vaccines, 77.5 percent receive the first dose of DPT, and 58.5 percent receive the third phase of DBT vaccines. The case is the same with polio. In an estimated 30 percent fall, the BCG vaccines have gone down to 63 percent, while the fall in all the three phases of DBT can also be seen. Measles vaccines were received by only 56.7 percent of children. Approximately forty three percent received all basic vaccinations. The babies who were born during this lockdown period and who were unable to get vaccines on time are likely to suffer from susceptibilities to various deadly diseases throughout their lives if appropriate interventions are not made at the right time. They may also suffer from deficits in mental, psychological, and physical development due to anaemic mothers who didn’t receive iron and folic acid tablets on time or who missed several ANC cares. Hence appropriate interventions are very much required.

|

3. Conclusions

- Covid-19 and the nationwide lockdown has had an adverse impact on the utilization of maternal health services. Suspended transport facilities, restriction on movement, limited healthcare facilities and unavailability of medicines at medical stores created barriers for pregnant women’s access to antenatal care, institutional deliveries and post-natal care. In this study, extrapolations have been made by the authors about the estimated fall in maternal health services. It is estimated that ANCs and PNCs have declined by 30 to 40 percent, with only 40.96 percent and 35.84 percent of women receiving four or more ANCs, respectively, and 52.08 percent and 45.57 percent of women receiving a postnatal check within the first two days of birth. A sharp decline can also be seen in institutional births. Overall, 55.23 percent and 47.34 percent of women chose institutional delivery, representing a 30 and 40 percent decrease from the 2015-16 NFHS-4 survey, respectively. During the lockdown, labor and deliveries at homes were increased. In the estimated data, a huge rise in labor and delivery at home can be seen in both urban and rural areas. With the increase of labor and delivery at homes, the risk of improper labour at home has also risen. Unsafe deliveries at home will lead towards a society where there would be an increased possibility of more maternal deaths and child mortality. The covid 19 pandemic has taught us that health preparedness should always be ready to deal with such kinds of pandemic. While dealing with public emergencies, the government should also focus on other aspects of people’s health, and this can only be done when, on usual days, the healthcare system functions fully with efficiency and equity. The government should be more focused on the vulnerable sections of society, i.e., women and children. In any situation, pregnant women should be provided with access to basic healthcare facilities. The damage is already done. The government should make it a priority to identify all such women who did not receive the most critical medical care during the lockdown and subsequent period and to provide any compensatory care that may have played a role in improving the situation. The new born will certainly need extra care in the days to come.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML