-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Sociology

p-ISSN: 2169-9704 e-ISSN: 2169-9739

2021; 11(2): 82-89

doi:10.5923/j.ijas.20211102.03

Received: Sep. 28, 2021; Accepted: Oct. 17, 2021; Published: Dec. 24, 2021

Exploring the Effects School Life Records on University Admission Policies and Students’ Experience

Kim Se Jeong

Osaka University Graduate School, Graduate School of Human Sciences of Osaka University

Correspondence to: Kim Se Jeong, Osaka University Graduate School, Graduate School of Human Sciences of Osaka University.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study explored the current meanings attached to the making of school life records, and their significance in Korea’s high school education. Semi-structured interviews were carried out with teachers and students of Public General X High School. Findings suggest that students’ school life records encourage discrimination of students on the basis of their performance. School life records are also found to function as instruments of student control and supervision. The practice of making of school life records is anchored in students having good academic performance. Hence, students’ performance is a fundamental factor influencing the creation of school life records, mainly as a result of Korean education’s score-centred mentality. In addition, school records only tend to be significant to students with better grades, particularly since these records are a requirement for university admission. School life records are also found to function as tools for student control and supervision. Therefore, the conventional system of top–down education and the university admission system must be improved. Findings from this research also show that it is necessary to change the education structure fundamentally to change the curriculums of elementary, middle, and high schools according to the government’s university entrance policies and systems.

Keywords: Qualitative Study in School, School life records in Korea, University Admission System in Korea, Exclusion and Control in School, Education Innovation in East Asian Countries

Cite this paper: Kim Se Jeong, Exploring the Effects School Life Records on University Admission Policies and Students’ Experience, International Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. 11 No. 2, 2021, pp. 82-89. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20211102.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Since it’s unveiling in 1945, the university entrance evaluation and admission system in Korea has evolved from a standardized system primarily focused on test scores to one that integrates additional important elements. The current comprehensive evaluation system that is designed for high school life records for university admission (“comprehensive selection of school life records”) was preceded by 16 revisions, commensurate with historical transitions in governments in Korea. To improve university admission system, focus has been placed on relieving excessive competition. The goal is to normalize public education and reduce private education expenses. Comprehensive selection of school life records became a necessity because of the simplification policy for students’ admission to universities in 2013. In 2014, 18.7% freshmen received admission via the university admission system. The number increased to 32.1% in 2018, making it one of the most important axes in the current university admission system (Korea University Education Council, 2016). The policy goals of the government include “burden relief for students and parents, normalization of high school education, ensuring autonomy and diversity of student selection for the universities and also reinforcing connection between high school and university” (KUEC, 2016, p.1). The comprehensive selection of school life records is considered a part of the official plan to improve the overall admission system (Jung, Choi, Lee, &Jung, 2012). The implementation of the system of comprehensive selection of school life records led to a new paradigm for the selection of university students. Universities turned away from a mechanical student selection system that focused on academic grades and took into account students’ potential and talent, ideology of the university establishment, and student selection characteristics to select students who fit their institution better (Kim, 2008). Conventional curriculum-oriented education courses in high schools were transformed with the implementation of non-curriculum materials, such as after-school activities, characterization programs, and the operation of creative experiences. To help students with their academic or career decisions more systematically, special counsellors were placed in high schools nationally. Official language exam scores, out-of-school competition records, overseas volunteer service activities, and other private education activities were exempted from listing in school life records to restrain their influence on university admission. This led teachers to write school life records in a more detailed manner to reflect students’ characteristics. An underlying outcome of this measure included an increased recognition of the significance of school life records. Recently, however, questions regarding selection fairness, professionalism of admission officers, ethicality of the system, and encouragement of private education expenses have continued to be raised.In 2015, the admission officer system was changed to comprehensive selection of school life records. While the identification of changes in high schools and the challenges resulting from the new system is crucial to improving the university admission policies of Korea in the future, there is a dearth of studies that have conclusively investigated the issue. This provides the present study with a rationale to investigate how high school teachers responsible for these records create and review the meaning and purpose of school life records. Also investigated within this purview are the problems of exclusion within the educational field, specifically when it comes to creating and reviewing school life records. The study has significant practical implications in terms of closing knowledge gaps in the current state of education and its problems in Korea and other countries in East Asia such as Japan and China. Like Korea, these countries also experience “examination wars” owing to the inadequacies of their educational policy. They also have a social structure that is similar to that of Korea.

2. Materials and Methods

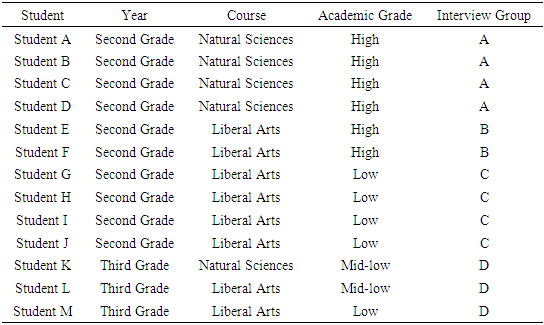

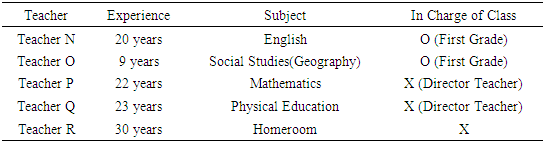

- Comprehensive Selection of School Life Records as a New University Admission SystemIn 2015, “the admission officer system” was changed to “the comprehensive selection of school life records” in alignment with the simplification policy for university admission. The changes also became a necessity on the backdrop of the need to improve student selection and operation methods. The comprehensive selection of school life records focused on “material selection,” such as school records. In the final format of the comprehensive selection of school life records, a decision was made to utilize “admission officers and others” in the new system. However, with the change of the name, a significant decline in negative public perception of the significance of admission officers resulted, as knowledge of the significance of school records increased (Cha, 2016).In the new system, admission officers and other examiners comprehensively had grater authorization to evaluate students’ academic subjects, cover letters, teacher’s recommendations, and interviews while simultaneously focusing on non-academic areas recorded in the students’ school records. Conversely, in the selection of students on the basis of subjects, students are evaluated using academic grades. This allows universities to decide their ratio of reflection on score-based evaluations for purposes of selecting students depending on selection criteria. Although the comprehensive selection of school life records and selection of students on the basis of subjects use school records as their main sources, they have different approaches for student evaluation. While the latter focuses on quantitative evaluation of academic grades in school records, the former focuses on qualitative and comprehensive evaluation by reflecting academic and non-academic areas (Korea University Education Council, 2014). The Broad Meaning of Social ExclusionThe concept of social exclusion denotes a process wherein certain individuals or groups are systematically excluded from their rights, opportunities, and resources that are considered to be accessible to any member of society - such as housing, employment, health, civic participation, democratic participation, and due process (Todman et al., 2009). The concept concentrates on “a multi-dimensional process of progressive social disruption” that isolates groups or individuals from social relationships and systems, excluding them from full participation in ordinary activities in their communities (Silver, 2007). While the concept of social exclusion has been introduced to analyze poverty or economic polarization within a welfare state, the subject of its analysis is rather a norm-related phenomenon that defines highly non-material social relationships and contexts. The same is true for school education, which is essentially a small society.OverviewThis study carried a qualitative research using participant observation and interviews to explore the reality of on-site education in high schools. The study period was divided into two parts: March 1–April 10, 2017 and September 4–October 9, 2017. Because schools in Korea start in March, I familiarized myself with X high school, which was the study location, from March to April. From September to October, I re-adapted to the school atmosphere while selecting interviewees among students and teachers and conducted full interviews. During fieldwork conducted from March to April 2017, I visited the school each day in line with the scheduled school hours to undertake an observation of its atmosphere and characteristics and to establish a close rapport with students and teachers. I interacted with students in the first, second, and third grades. Additionally, with the permission of the principal, I received a designated space in the teachers’ room to interact with teachers.Study SubjectsX High School is a public general high school (so-called humanities high school) located in B city, Gyeonggi-do, where high schools are standardized. About 1,000 students attend the school. The academic competition among students is high, and the school life records show high enthusiasm for university admission. This is reflected in parents as well. I set the study target as the second and third grades because of the keyword of this study, “school life records.” This required that I should have information about students who are familiar with their school lives. As students in their second and third grades are more sensitive about their university admission, I considered that they must have the highest interest in the school life records. Ten interviewees from the second grade and three interviewees from the third grade were selected. Interviewees from the third grade were reluctant to be interviewed, as reflected in these statements: “It is embarrassing to reveal my school life records,” “I have no time to discuss my school life,” and “it is frightening to see that my school life is used for a study.”In Online Resource 1, I included the academic records of ranked subjects with the percentages in parenthesis, following the percentage of subject rankings that students completed in the semester. (1st Grade: less than 4%; 2nd Grade: 4%–11%; 3rd Grade: 11%–23%; 4th Grade: 23%–40%; 5th Grade: 40%–60%; 6th Grade: 60%–77%; 7th Grade: 77%–89%; 8th Grade: 89%–96%; and 9th Grade: 96%–100%). Generally, 1st to 2nd grades are considered high ranks; 3rd to 4th grades are middle ranks, and 5th to 6th grades are mid-low ranks, and 7th to 9th grades are the lowest ranks.In this study, I tried to balance the number of students in academic courses and grades. However, students with good academic grades (high rank) and lower academic grades (mid-low and low ranks) had substantial differences with the contents of school life records and their awareness of them. Students had to be divided into groups of high, mid-low, and low academic grades. Additionally, although the interviewees were grouped among students with similar academic grades, they were also grouped with students with available interview times depending on constrained condition (time, place, position, etc.) and schedule. As for the teacher interviewees, two homeroom and two director teachers in charge of academic subjects and one career counselor were selected. Because teachers also had opinions of “it is frightening to become a study subject,” I experienced a difficulty in recruiting interviewees for the study.As homeroom and subject teachers are responsible for making school life records in Korea, both were selected as interviewees. Teachers in charge of subjects mainly described “details of special notes in subjects” of academic learning development status in the school life records. Further, each teacher was responsible for managing and guiding various student activities and recording them in school life records. The study met underlying ethical consideration. Research Ethics Committee of Kyosei Studies, Graduate School of Human Sciences, Osaka University approved the study, under Approval number - OUKS1715. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before participation, subject to a review meeting held on 20 July, 2017. All research procedures were carried out in accordance with the Helsinki declaration.

3. Results

- The results and discussion may be presented separately, or in one combined section, and may optionally be divided into headed subsections. This study aimed to clarify the difference in perceptions between the teacher, who prepares the school life record, and the student, who is the object of the record.

|

|

(One of Group A interviews, 9.11.2017.)“For example, when there are programs or activities at school, teachers only accept participants in the order of academic grades. This is to make sure students with good academic grades can participate more in programs and activities to have greater descriptions on the school records. That is how teachers manage school records focusing on students with good grades. I am being honest.” Student C

(One of Group A interviews, 9.11.2017.)“For example, when there are programs or activities at school, teachers only accept participants in the order of academic grades. This is to make sure students with good academic grades can participate more in programs and activities to have greater descriptions on the school records. That is how teachers manage school records focusing on students with good grades. I am being honest.” Student C (One of Group A interviews, 9.11.2017.)From Student D and Student C’s response, it can be inferred that the process of making of school life records centres on students having good academic performance and that this atmosphere is already present among students. Other group interviews also revealed a similar trend.“Unconditionally, students with good grades have more contents in their school records. Those with 1st, 2nd, or at least 3rd grades in their academic scores always have more on their records with unconditional good comments from teachers. If you have poor academic grades, they do not bother looking at the records because there’s nothing in them anyway.” Student F

(One of Group A interviews, 9.11.2017.)From Student D and Student C’s response, it can be inferred that the process of making of school life records centres on students having good academic performance and that this atmosphere is already present among students. Other group interviews also revealed a similar trend.“Unconditionally, students with good grades have more contents in their school records. Those with 1st, 2nd, or at least 3rd grades in their academic scores always have more on their records with unconditional good comments from teachers. If you have poor academic grades, they do not bother looking at the records because there’s nothing in them anyway.” Student F (One of Group B Interviews, 9.14.2017)“Once, I thought I participated well in one of the subjects, but when I looked up my school records later there were no special notes about it. When I asked my teacher, the answer was, “Your subject score is less than 30 points, so I wrote nothing.” I was so frustrated. At that time, I regretted all my efforts and lost all my drive to study.” Student J

(One of Group B Interviews, 9.14.2017)“Once, I thought I participated well in one of the subjects, but when I looked up my school records later there were no special notes about it. When I asked my teacher, the answer was, “Your subject score is less than 30 points, so I wrote nothing.” I was so frustrated. At that time, I regretted all my efforts and lost all my drive to study.” Student J (One of Group C Interviews, 9.14.2017)“Teachers write good remarks in the school records of those with good academic grades. There’s nothing in the records for those with poor grades.” Student M

(One of Group C Interviews, 9.14.2017)“Teachers write good remarks in the school records of those with good academic grades. There’s nothing in the records for those with poor grades.” Student M (One of Group D Interviews, 9.14.2017)Participants’ responses suggest that the primary focus in making school life records is on students who have good academic grades. Teachers wrote either nothing or only a couple of lines for those with poor grades. Teachers had a greater degree of interest in students at the top three levels (levels 1, 2, and 3) of academic performance than the others. Teachers included positive remarks in the school records of students with good grades without much doubt. The students’ perceptions indicate that academic performance is a crucial consideration in the creation of school life records, possibly because of the prevalence of a score-centered mentality in Korean education. Although school education administration has tried to eliminate this bad influence, most school evaluations are based on students’ academic grades.Interviews conducted with teachers who had described the school records by themselves also confirmed the differences in the school records of students with different academic grades.“To be honest, I do make an announcement for everyone when there are intramural competitions or activities, but I also call students up to the 5th rank and recommend them to participate in the events for their good school records. It is difficult for teachers to manage school records if students with poor grades are also to be included.” Teacher N

(One of Group D Interviews, 9.14.2017)Participants’ responses suggest that the primary focus in making school life records is on students who have good academic grades. Teachers wrote either nothing or only a couple of lines for those with poor grades. Teachers had a greater degree of interest in students at the top three levels (levels 1, 2, and 3) of academic performance than the others. Teachers included positive remarks in the school records of students with good grades without much doubt. The students’ perceptions indicate that academic performance is a crucial consideration in the creation of school life records, possibly because of the prevalence of a score-centered mentality in Korean education. Although school education administration has tried to eliminate this bad influence, most school evaluations are based on students’ academic grades.Interviews conducted with teachers who had described the school records by themselves also confirmed the differences in the school records of students with different academic grades.“To be honest, I do make an announcement for everyone when there are intramural competitions or activities, but I also call students up to the 5th rank and recommend them to participate in the events for their good school records. It is difficult for teachers to manage school records if students with poor grades are also to be included.” Teacher N (Interview with Teacher N, 9.17.2017)“It is not our duty to make records for all students. We are supposed to make school records for students with good grades because it may be useful as a selection material for university admission only to them. Teachers usually do not write anything in school records for students with mid-to-low grades, but even if I am a teacher in charge, I cannot force other teachers to do anything. I raise two children myself, and I worry that they might not be able to get the academic grades that are worthy of school records.” Teacher P

(Interview with Teacher N, 9.17.2017)“It is not our duty to make records for all students. We are supposed to make school records for students with good grades because it may be useful as a selection material for university admission only to them. Teachers usually do not write anything in school records for students with mid-to-low grades, but even if I am a teacher in charge, I cannot force other teachers to do anything. I raise two children myself, and I worry that they might not be able to get the academic grades that are worthy of school records.” Teacher P (Interview with Teacher P, 9.18.2017)“Several students think that teachers create school records focusing on students with good academic grades, and I believe this is true. From a teacher’s perspective, school records are only significant to students with good grades, so teachers know that it is better to make records only for those students. Rather than writing down something for all students in their school records, making and managing the records of students with high grades who are most likely to use them for university admission is what teachers generally think of.” Teacher Q

(Interview with Teacher P, 9.18.2017)“Several students think that teachers create school records focusing on students with good academic grades, and I believe this is true. From a teacher’s perspective, school records are only significant to students with good grades, so teachers know that it is better to make records only for those students. Rather than writing down something for all students in their school records, making and managing the records of students with high grades who are most likely to use them for university admission is what teachers generally think of.” Teacher Q (Interview with Teacher Q, 9.19.2018)The interview results of teachers indicate their perceptions of the usefulness of school records for students’ university admission. These data show that teachers implicitly agreed to the culture of producing school records only for students with excellent academic grades to enter so-called prestigious universities. However, in Korea, school records provide significant data both for university admission and for employment (Park, Um, Joo, 2015). Therefore, teachers’ current practice of making records can be a major problem because fair and comprehensive recording of the activities and lives of all students at school is necessary for various uses. Furthermore, teachers should not overlook the possibility that such attitudes may cause troubles for students in the future.Teachers equate the admission of students to prestigious universities to social success that would become a great advantage in life. This notion is rooted in academic elitism and achievement-oriented mentality that are chronic problems in the Korean education system. Career courses and counselors in schools aimed at promoting various avenues of growth for students are not effective because students are not receiving practical help from the system for their future. The goal of the education policy of promoting the importance of school records was to induce students to conduct their school lives faithfully while school education respects the personality and uniqueness of each student. However, the skewed primacy attributed to university admission and academic grades indicate the necessity to explore the underlying problems in the Korean social structure, school education policy, and university admission.Other teachers also provided perspectives on why they should prioritize school records of students with good academic grades. For instance, Teach R said:“Of course, we write good comments on the school life records for students with good grades and not a lot of comments for students with poor grades because the latter cannot enter a good university anyway. I can only give bad comments for students with poor grades. Students have different levels of vocabulary when I make one of them present in class. Some have poor levels of academic achievement. Students with mid-to-low academic grades are often distracted. I have nothing to write for them. This is why teachers generally give highly positive comments in the school records of students who are at levels 1 and 2 with regard to academic scores. We usually focus on students with good academic grades and supervise them. This is not just what I think; during regular teachers’ meetings, we often discuss this issue.” Teacher R

(Interview with Teacher Q, 9.19.2018)The interview results of teachers indicate their perceptions of the usefulness of school records for students’ university admission. These data show that teachers implicitly agreed to the culture of producing school records only for students with excellent academic grades to enter so-called prestigious universities. However, in Korea, school records provide significant data both for university admission and for employment (Park, Um, Joo, 2015). Therefore, teachers’ current practice of making records can be a major problem because fair and comprehensive recording of the activities and lives of all students at school is necessary for various uses. Furthermore, teachers should not overlook the possibility that such attitudes may cause troubles for students in the future.Teachers equate the admission of students to prestigious universities to social success that would become a great advantage in life. This notion is rooted in academic elitism and achievement-oriented mentality that are chronic problems in the Korean education system. Career courses and counselors in schools aimed at promoting various avenues of growth for students are not effective because students are not receiving practical help from the system for their future. The goal of the education policy of promoting the importance of school records was to induce students to conduct their school lives faithfully while school education respects the personality and uniqueness of each student. However, the skewed primacy attributed to university admission and academic grades indicate the necessity to explore the underlying problems in the Korean social structure, school education policy, and university admission.Other teachers also provided perspectives on why they should prioritize school records of students with good academic grades. For instance, Teach R said:“Of course, we write good comments on the school life records for students with good grades and not a lot of comments for students with poor grades because the latter cannot enter a good university anyway. I can only give bad comments for students with poor grades. Students have different levels of vocabulary when I make one of them present in class. Some have poor levels of academic achievement. Students with mid-to-low academic grades are often distracted. I have nothing to write for them. This is why teachers generally give highly positive comments in the school records of students who are at levels 1 and 2 with regard to academic scores. We usually focus on students with good academic grades and supervise them. This is not just what I think; during regular teachers’ meetings, we often discuss this issue.” Teacher R (Interview with Teacher R, 9.19.2017)The basic function of school records is to promote better growth and development of student via teacher–student consultation. However, teachers appear to have prejudice against students with poor academic grades according to Teacher R’s comment, where the teachers did not show any efforts to observe those students in a positive manner and describe what they see differently in school life records.Korean schools do have an educational course on applying different contents based on grades and offering special courses for students in an academic slump. However, its impact is not much, as is evident from the interview with Teacher R. Thus, the goal of “education that grows together” part of the current education policy would not work properly. It required teachers to make great efforts to nurture all students by observing academic, social, and various other capabilities and characteristics to describe them in the school records.School Life Records as a Means of Student Control and SupervisionThis passage focuses on the function of school records in high schools and the purpose they serve.“Teachers are almost threatening us using school records by saying whatever we do—like not doing homework—everything will go into the school records. If I do something wrong, they say it would be recorded.” Student B

(Interview with Teacher R, 9.19.2017)The basic function of school records is to promote better growth and development of student via teacher–student consultation. However, teachers appear to have prejudice against students with poor academic grades according to Teacher R’s comment, where the teachers did not show any efforts to observe those students in a positive manner and describe what they see differently in school life records.Korean schools do have an educational course on applying different contents based on grades and offering special courses for students in an academic slump. However, its impact is not much, as is evident from the interview with Teacher R. Thus, the goal of “education that grows together” part of the current education policy would not work properly. It required teachers to make great efforts to nurture all students by observing academic, social, and various other capabilities and characteristics to describe them in the school records.School Life Records as a Means of Student Control and SupervisionThis passage focuses on the function of school records in high schools and the purpose they serve.“Teachers are almost threatening us using school records by saying whatever we do—like not doing homework—everything will go into the school records. If I do something wrong, they say it would be recorded.” Student B (One of Group A Interviews, 9.11.2017)“We usually do what teachers tell us to do because they always say that what we do will be described in the school records. It is as if teachers are trying to control students with school records. I really hate that teachers always threaten us, saying that they will mention it our records when we do not complete homework or do something wrong.” Student F

(One of Group A Interviews, 9.11.2017)“We usually do what teachers tell us to do because they always say that what we do will be described in the school records. It is as if teachers are trying to control students with school records. I really hate that teachers always threaten us, saying that they will mention it our records when we do not complete homework or do something wrong.” Student F (One of Group B Interviews, 9.14.2017)“Teachers always say no matter what you do, good or bad, everything will go into the school records. It feels as if we are being oppressed and threatened. So stressful.” Student K

(One of Group B Interviews, 9.14.2017)“Teachers always say no matter what you do, good or bad, everything will go into the school records. It feels as if we are being oppressed and threatened. So stressful.” Student K (One of Group D Interviews, 9.14.2017)The high frequency of the usage of the term “threatening” by students during the interviews indicates that students thought of school records as a tool used by teachers to control them. This is a strong indicator that school records do not act as a means to help students with their lives and future plans or promote their overall development. Therefore, students’ perception of school records as a mechanism to supervise their behaviors is accurate. While teachers may be using comments such as “if you do OO, I’ll put that in the records” to induce students to get involved in activities, the overuse of such comments put stress on students rather than being motivational statements.Here is an excerpt of a teacher’s thoughts on students’ impression of being threatened, controlled, and supervised through school records.“I actually say to my students, “If you do this, I’ll write that down in the school records”… These days, students understand that the contents of school records are crucial, and I often use that comment to motivate them. However, because the only way to control students is school records, I have no choice but to threaten students with it rather than use it as a means to motivate. Because the school records have gained importance, teachers can use them to urge students to participate in classes or school activities.” Teacher N

(One of Group D Interviews, 9.14.2017)The high frequency of the usage of the term “threatening” by students during the interviews indicates that students thought of school records as a tool used by teachers to control them. This is a strong indicator that school records do not act as a means to help students with their lives and future plans or promote their overall development. Therefore, students’ perception of school records as a mechanism to supervise their behaviors is accurate. While teachers may be using comments such as “if you do OO, I’ll put that in the records” to induce students to get involved in activities, the overuse of such comments put stress on students rather than being motivational statements.Here is an excerpt of a teacher’s thoughts on students’ impression of being threatened, controlled, and supervised through school records.“I actually say to my students, “If you do this, I’ll write that down in the school records”… These days, students understand that the contents of school records are crucial, and I often use that comment to motivate them. However, because the only way to control students is school records, I have no choice but to threaten students with it rather than use it as a means to motivate. Because the school records have gained importance, teachers can use them to urge students to participate in classes or school activities.” Teacher N (Interview with Teacher N, 9.17.2017)“For the past 6–7 years, teachers have been deprived of ways to control students because of the issue of student human rights. Even if students make mistakes, we can no longer punish them or expel them from school like before. Therefore, we try to control them by saying “that will go into the school records.” Only then students listen to what we have to say to them.” Teacher Q

(Interview with Teacher N, 9.17.2017)“For the past 6–7 years, teachers have been deprived of ways to control students because of the issue of student human rights. Even if students make mistakes, we can no longer punish them or expel them from school like before. Therefore, we try to control them by saying “that will go into the school records.” Only then students listen to what we have to say to them.” Teacher Q (Interview with Teacher Q, 9.19.2017)Therefore, at the start of the semester, teachers may say “if you do OO, I’ll put it in the records” to motivate students to participate more in classes and school activities. However, teachers themselves have admitted that they use school records to control and supervise students. In Gyeonggi-do, the Korean education administration announced the Student Human Rights Ordinance in 2010 to uphold the prohibition of corporal punishment by teachers, prohibition of dress and hair regulation, and respect for freedom of students. There is also criticism that teacher’s rights and influences in school have diminished because of the ordinance. This may have paved the way for teachers to use school records to discipline students, which in turn has resulted in students feeling oppressed by teachers.It emerges from the participants’ responses that even as the most important goal of the government in raising the importance of school records was to encourage the positive and autonomous growth of students by inducing them to participate voluntarily in various school activities, the implementation of the policy has veered away from it. School records in general high schools have lost their original meaning and role. Therefore, an accurate understanding of the government’s policy of enhancing the significance of school records is necessary.

(Interview with Teacher Q, 9.19.2017)Therefore, at the start of the semester, teachers may say “if you do OO, I’ll put it in the records” to motivate students to participate more in classes and school activities. However, teachers themselves have admitted that they use school records to control and supervise students. In Gyeonggi-do, the Korean education administration announced the Student Human Rights Ordinance in 2010 to uphold the prohibition of corporal punishment by teachers, prohibition of dress and hair regulation, and respect for freedom of students. There is also criticism that teacher’s rights and influences in school have diminished because of the ordinance. This may have paved the way for teachers to use school records to discipline students, which in turn has resulted in students feeling oppressed by teachers.It emerges from the participants’ responses that even as the most important goal of the government in raising the importance of school records was to encourage the positive and autonomous growth of students by inducing them to participate voluntarily in various school activities, the implementation of the policy has veered away from it. School records in general high schools have lost their original meaning and role. Therefore, an accurate understanding of the government’s policy of enhancing the significance of school records is necessary.4. Discussion

- The study met its objective of investigating how high school teachers create and review the meaning and purpose of school life records, and the resultant problems of exclusion within the educational field, specifically when it comes to creating and reviewing school life records.The first theme that emerges from the participants’ responses is the impact of selective records in encouraging discrimination of students. It emerges that teachers make school life records depending on student’s academic performance, and that incidences of exclusion based on academic performance while making school life records is rife. A majority of the student participants were of the view that teachers’ practice of making school life records depending on student’s academic performance leads to discrimination, particularly when teachers only select students to participant in certain academic programs depending on their academic grades. Participants’ responses suggest that the primary focus in making school life records is on students who have good academic grades. This seemingly prevalent pattern of practice, as construed from the participants, also demonstrates that the practice of making of school life records in Korea rests on students having good academic performance. Accordingly, this appears to have led to a situation where students with good grades have more contents in their school records than those with lower grades. Some of the participants were of the view that students with better grades tended to have more unconditional good comments from teachers on their records. This was identified to be a cause for worry for some participants who revealed that they tended to be discouraged by this level of bias among teachers, particularly when they had expected fair comments only to find none.Additional concerns related to teachers’ discriminatory practices also emerged from student participants’ concerns that teachers tend to demonstrate more interest in establishing cordial relationship with students at the top three levels (levels 1, 2, and 3) of academic performance than those in the lower levels. This seems to happen in situations where teachers include positive remarks in the school records of students with good grades, which plays a role in setting up an atmosphere of cordiality.These clearly show that the logic of social exclusion is being applied in the field of school education and that students with low academic performance are being excluded from the whole school. Teachers selectively record school life records, which are important selection materials for college entrance exams based on academic performance and do not record students with low academic performance, which will result in primary exclusion in the overall university selection process. Consequently, low-performing students are dismissed as out-of-interest beings in school, and school life records are used as a means of student control to prevent deviations and maintain college entrance and school systems.An additional emerging theme from participants’ coded responses is that students’ performance is a fundamental factor influencing the creation of school life records, mainly as a result of Korean education’s score-centered mentality (Ueno et al., 2014). Data from teachers’ responses offers insights that corroborate those of the students. The teachers interviewed revealed that their criteria for making the school records were more subjective, as they were primarily guided by their perceptions of students’ performance. Indeed, they appeared to have a general agreement that it is difficult for teachers to manage school records if students with poor grades are also to be included. However, since they are charged with making records for all students, they are more motivated to make school records for students with better grades.In addition, a majority of the teachers were of the opinion that school records only tend to be significant to students with better grades, particularly since these records are a requirement for university admission. Therefore, teachers consider it a necessity to make records only for better performing students, who expect to join universities (Nakada, 2014). As a result, students with low academic performance who face primary exclusion from school are likely to experience exclusion from the university and the society because of their uninviting school records. Indeed, while school life records are intended to assist in the university admission process and to normalize public education, the educational system is commonly perceived as excluding students with low academic grades by creating an environment where they are excluded from entering the university.To this extent, it also emerges that teachers generally perceive school records as useful for students’ university admission, which influences their decision to focus on making better school records for those students they believe have greater prospects to join prestigious universities. This apparent scenario, as revealed from teachers’ perspectives, demonstrates that teacher cognition is conditioned or structured to pay less attention to students who are considered as nonperformers.Yet, students’ responses reveal that this practice can be detrimental to their career prospects, as it discriminates between students perceived to have low and those perceived to have high academic performance. A convincing reason inferred from students’ responses is that as much as school records provide significant data for university admission, they also determine their future job prospects. This perspective is adequately supported by related research (Park et al, 2015). Hence, teachers’ current practice of making records is interpreted as being unfair and detrimental to students with lower grades. It also goes against the basic function of school records, which is to promote better growth and development of student via teacher–student consultation (The Herald Business, 2020). The second theme that emerges from the participants’ data is that school life records are basically tools for student control and supervision. From data coding, it emerged that majority of student participants used the term “threatening,” which is construed to indicate that students view school records as a tool used by teachers to control them. This indicates that some students do not view school records as designed to help them in their lives and future plans or to promote their overall development (Nakada, 2014). A compelling explanation was revealed from teachers’ responses, whereby some of them revealed that they tend to coerce students to demonstrate certain behaviours by threatening to write harsh comments in the records. It is deduced from the participants’ responses that while the most vital goal of the government in promoting the use of school records is to encourage the positive and autonomous growth of students by inducing them to participate voluntarily in various school activities, teachers use school records as instruments of social control.Therefore, a careful consideration of the effects of school records in student control is necessary, as recording school life records appears to be a means for controlling students. In general, students with positive academic performance self-manage their school records for college entrance examinations, yet they are forced to also avoid contravening the demands of their teachers to avoid bad listing in the records. As previously mentioned, the majority of problems in the school education system are derived from the top–down implementation of educational policies (i.e., government-led types) created by the establishment. Correspondingly, some of Korean government’s education policies have not actually had a positive impact in the field of education. The reason is that the actual conditions of the educational field have not reflected in government policies.

5. Conclusions

- Students’ school life records encourage discrimination of students on the basis of their performance. School life records are also found to function as instruments of student control and supervision. The practice of making of school life records is anchored in students having good academic performance. Hence, students’ performance is a fundamental factor influencing the creation of school life records, mainly as a result of Korean education’s score-centred mentality. This is found to have led to a situation where students with good grades have more favourable contents in their school records than those with lower grades, who have harsh comments. Yet, this is a cause for worry for students in general, as they tend to be discouraged by the high level of unpredictable bias among teachers. On the other hand, instances where teacher include positive remarks in the school records of students with good grades encouraged an atmosphere of cordiality. This, however, makes students with low grade to feel excluded. These clearly show that the logic of social exclusion is being applied in the field of school education and that students with low academic performance are being excluded from the whole school. There is also a shared conception among some teachers in Korea that school records only tend to be significant to students with better grades, particularly since these records are a requirement for university admission.Therefore, there is a proclivity to make historical records only for better performing students, who expect to join universities. These show that while school life records are designed to assist in the university admission process and to normalize public education, the educational system is commonly perceived as excluding students with low academic grades by creating an environment where they are excluded from entering the university. Teachers’ practice of selective determination of the quality of content for students’ historical records is detrimental to low-performing students’ career prospects, as it discriminates between students perceived to have low and those perceived to have high academic performance.School life records are also found to function as tools for student control and supervision. This has led to a scenario whereby some students do not view school records as designed to help them in their lives and future plans or to promote their overall development, but to transform them into subjects of control. Teachers have a tendency to use the records to coerce students to demonstrate certain behaviours.

6. Research Implications

- Given the current reality of education in Korea, not many studies have covered topics and methods like the ones we have seen thus far. This study will have great implications for the Korean college entrance exam format centered on the school records and the various problems that arise at high school education sites. The study has significant practical implications with respect to closing knowledge gaps in the current state of education and its problems in Korea and other countries in East Asia such as Japan and China. Like Korea, these countries also experience “examination wars” owing to the inadequacies of their educational policy.

7. Research Limitations and Future Research

- In spite of the good degree of detail attained by this research, the results demonstrate a number of limitations. A major limitation draws from the single-cases study method used, whereby focus was placed in one institution: Public General X High School. The limited study sample used also exposed the results to additional limitations, of limited research generalisability. In any case, the case study is still considerably value as it provides results showing that Korea’s conventional system of top–down education and the university admission system should be improved, particularly with regard to current practices that teachers employ in making school life records.Future research could focus on using multiple case study methods to investigate a larger sample in order to confirm findings in this research particularly with respect to compressive selection of school life records and school life records, suspicions of fairness, and problems concerning the actual conditions of school education sites.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML