-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Sociology

p-ISSN: 2169-9704 e-ISSN: 2169-9739

2021; 11(2): 33-45

doi:10.5923/j.ijas.20211102.01

Received: Jul. 12, 2021; Accepted: Jul. 27, 2021; Published: Jul. 31, 2021

Awareness of Campus Safety Services Among Students in a Midwestern University in the United States

Zachary Christo, Anna Jensen, A. Olu Oyinlade

Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Nebraska, Omaha, USA

Correspondence to: Zachary Christo, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Nebraska, Omaha, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study investigated university students’ awareness of campus safety services offered by the Department of Campus Safety at the University of Nebraska, Omaha, in the United States. An online electronic survey was administered, and participants were selected via a convenience sampling method. Only undergraduate and graduate students who were at least 19 years old and had completed at least two semesters of coursework at the university were solicited for participation in this study. The ANOVA and regression analyses were utilized to assess the extent to which selected independent variables were significant predictors of five awareness dependent variables in the study. Findings indicated that student tenure on campus (measured in terms of “semesters completed”) was the only statistically significant predictor of one awareness dependent variable (personal safety assistance services), which suggested that students paid close attention to safety services that were most relevant to their needs as commuters. No other independent variable significantly predicted any other dependent variable in the study. Future research is encouraged to replicate this study with the hope that our findings will either be confirmed or controverted. We also encourage future research to employ random sampling methods and to obtain a larger sample size to improve the generalizability of findings.

Keywords: Safety, Campus safety, Safety awareness, Campus security, Student-safety, Campus crime, Crime reporting

Cite this paper: Zachary Christo, Anna Jensen, A. Olu Oyinlade, Awareness of Campus Safety Services Among Students in a Midwestern University in the United States, International Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. 11 No. 2, 2021, pp. 33-45. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20211102.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction and Literature Review

- This study1 attempts to uncover the extent to which students at one university in the midwestern region of the United States (US) were aware of safety services provided by the university’s safety department. Our interest in this study is consistent with those of the US populace as safety concerns at US educational institutions have been a major consideration for US universities in recent decades. In fact, it is safe to assume that high profile violent events in the US have impacted students at every stage of education, from the elementary school to the university, for several decades. Since the Columbine, Colorado, High School Massacre in 1999, school shootings have continued to shock the conscience of US schools, in events like the Virginia Tech shooting in 2007, the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012, and the 2018 shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. In addition to these examples of high-profile mass casualty violence, sexual assaults have also been commonly reported on university campuses (Carey, Durney, Shepardson, & Carey, 2015) and appears to have gotten much coverage in the US media. Thus, universities around the country appear to have an enduring challenge in maintaining a safe environment for students, faculty, and staff. Literature (e.g. Carey, Durney, Shepardson, & Carey, 2015; Fisher & Nassar, 1992) suggests that community perceptions of campus safety on university campuses have some noteworthy consequences, especially for students. Perhaps most notably is that the enrollment decision is influenced by community perceptions of campus safety outcomes. In the early 1990’s, Fisher and Nassar (1992) indicated that students prefered to attend campuses that were perceived as safe. Similarly, a study by Tseng, Duane, and Hadipriono (2004) indicated that students and their families were less willing to spend tuition dollars at universities that were perceived as unsafe. Despite much concern about campus safety, it appears that students are largely unaware of safety issues, and safety services provided by their campus security offices. For example, the study by Tseng, Duane, and Hadipriono (2004) which investigated crimes at two parking garages on the Ohio State University campus found that 79 percent of the study participants were largely unaware of the campus safety issues surrounding parking garages on their campus. The lack of knowledge of particular campus crimes, however, does not imply a lack of interest in campus safety by students. For example, consistently with other studies on campus safety (Carey, Durney, Shepardson, & Carey, 2015; Fisher and Nassar, 1992; Tseng, Duane, & Hadipriono, 2004), Chekwa, Thomas, and Jones (2013) found that 70 percent of university students surveyed reported that campus safety was a top priority as they navigated their university selection process. And, when asked about which security measures were considered most important to them, the students indicated that campus security officers were considered most important, followed by security cameras, emergency phones, and adequate security lighting. Also, 45 percent of respondents felt that security on campus was not adequate, while only 30 percent felt that security was adequate (Chekwa, Thomas, & Jones, 2013). Given the importance of safety and safety awareness to university students in the US, an understanding of the contributions of certain factors (antecedents) to campus safety awareness is of important consideration and analysis in this study. These factors, as briefly outlined in the proceeding paragraphs, are suggested to contribute to the degree of awareness of the campus community and safety outcomes for universities. These outcomes may include the university selection process, perceived safety of the learning environment, and likelihood of engagement in campus community activities. As such, the antecedents of campus safety awareness of university students are worthy of further investigation, especially given the potential impacts of the perceptions of campus safety on important university outcomes. Campus safety awareness may, perhaps, have its roots in the Clery Act which requires universities to collect and publicly report data on campus safety.The Clery ActIn 1986, Jeanne Clery, a student at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, was sexually assaulted and murdered in her university dormitory by a fellow student (Clery Center, 2017). This tragedy sparked a national discourse surrounding issues of campus safety on university campuses in the country. Eventually, congress passed The Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act of 1990 (aka the “Clery Act”). With the passing of the Clery Act, US universities became obligated to collect and disclose data about crimes occurring on university campuses to their communities (Clery Center, 2017). The ultimate intent of the Clery Act is to promote transparency and accountability through tracking and campus reporting of crime statistics, timely warnings to campus communities during emergencies, and educational initiatives designed to increase campus community awareness surrounding campus safety (Clery Center, 2017). If university safety officials can effectively educate their communities about campus safety and promote engagement in educational initiatives, they may be able to make a positive impact on campus safety outcomes at their respective campuses. In a continued effort to advocate for improved awareness of campus safety on university campuses, the US Congress commissioned an annual National Campus Safety Awareness Month, starting in 2008. This encourages further national dialogue regarding campus safety issues facing US universities (Clery Center, 2019) and serves as a yearly reminder of the importance of promoting community awareness of campus safety.Raising awareness also promotes better collaboration between campus communities and their respective campus safety departments, as it allows members of campus communities to play an active role in the design and modification of their current campus safety programs. Astor et al. (2005) suggested that community awareness of issues surrounding campus violence (and violence prevention programs) was an essential component of meaningful design and redesign of school safety structures. By creating a school violence procedure that maps violent hot spots, and conducting focus groups with students, teachers, staff, and safety officials can identify why violence is occurring in certain places on campus. Information obtained through monitoring or mapping may improve dialogues within the school community and allows for more effective violence interventions. Therefore, “a program that is adapted to the needs of the individual school and involves the entire school community is the most likely to be successful (Astor et al., 2005, p. 31). While the Clery Act had contributed to many positive changes in campus safety and safety awareness, Jennings, Grover and Pudrzynska (2007) asserted that more effort from university police, administration, and faculty was “necessary to raise awareness and promote prevention of campus victimization” (p. 204). Further, they asserted that university campuses could reduce the likelihood of victimization through structural changes such as centrally located walkways, walkway lighting, and student escort services. They reiterated that “efforts to make campuses safer must include a focus on both structural and social changes” (Jennings, Grover & Pudrzynska 2007, p. 204), and that schools should design educational programs to raise awareness of campus safety among university students (Jennings, Grover & Pudrzynska 2007).For the purpose of the current study, we combined the various campus safety services and educational initiatives into two major categories that form the dependent variables for ease of analysis. The first category, Emergency Services, contains the two subcategories of Awareness of Campus Emergency Reporting (ACER) and Awareness of Active Emergency Response Services (AAERS). The second category, Non-Emergency Services, describes the educational initiatives that are designed to prepare students for a wide range of safety concerns, as well as other non-emergency services offered to students (i.e., motorist assistance and campus escort services). We review the literature for these categories below.Emergency ServicesThe management of emergency safety situations seems to remain a challenge, even for the most well-trained and well-funded law enforcement organizations. The body of literature surrounding campus safety reporting on university campuses addresses a wide range of campus safety issues but appears to largely overlook how campus community awareness of campus safety may be impacting campus safety outcomes. For example, in the survey of 1,735 students at a large midwestern university, the findings of Hollister et al. (2017) suggested that efforts to improve student reporting to campus safety officials were important to campus violence prevention. The findings indicated that most students who witnessed safety concerns on campus did not report those concerns to authorities (87 percent), and of the students who witnessed assault or vandalism, only 20 percent and 19 percent, respectively, reported their observations. The findings indicate that the decision to report was not impacted by gender, ethnicity, or self-reported antisocial involvement. Further, the findings suggest that greater trust in campus police is associated with an increased tendency to report to campus authorities. However, the analyses in this study did not appear to take student awareness of how to report safety concerns into consideration. This is important since awareness of how to report safety concerns may influence the likelihood of reporting.Similarly, to Hollister et al. (2017), the survey of 391 women at a midsize, urban, university in the southeastern US, Buhi, Clayton, and Surrency (2009) found that approximately one-fifth of women indicated they had been victims of stalking at their university. Of the women who indicated experiences of stalking victimization, approximately half indicated that they did not report their victimization to anyone. While approximately half of these women did report, the findings indicated that only 7.3 percent reported to the police, and 12.2 percent reported to residence hall advisors. Also, about 90.2 percent sought help from friends and 29.3 percent included parents for their sources of help. The findings also indicated that women who lived on campus reported (24.3 percent) being stalked more than off-campus women residents (16.4 percent). Of the women who did not report or sought help: “The most common reasons for not seeking help were ‘I didn’t think the situation was serious’ (62.2 percent), followed by ‘I wanted to handle the situation myself’ (35.1 percent), ‘I didn’t want anyone else involved’ (29.7 percent), and ‘It was a private/personal matter’ (24.3 percent). The most common reasons for not seeking help from the police were ‘I believed the situation was too minor’ (64.9 percent), ‘I was afraid the person doing these things to me would seek revenge’ (40.5 percent), ‘It was a private/personal matter’ (29.7 percent), and ‘I thought the police wouldn’t believe me’ (18.9 percent). When women were asked to provide any other reasons for not seeking help from the police, one woman wrote, ‘I would not be receiving unwanted calls, etc., if I had not put myself in the bad situations in the first place . . . i.e., my fault.’ Another woman noted, ‘The guy seemed harmless—I just assumed he lacked social skills’” (Buhi, Clayton, & Surrency, 2009, p. 422).In addition, Sulkowski (2011) conducted a survey of 967 undergraduate college students at a large university in the southern US. Among the predictors Sulkowski investigated were campus connectedness, self-efficacy toward service, delinquency, and trust in the college support system as antecedents of willingness to report safety threats to campus authorities. Analysis indicated that approximately 70 percent of students surveyed were “at least somewhat willing” to report a threat to campus police. Sulkowski also found that students’ trust in the college support system, connectedness to campus, and self-efficacy toward service was positively related to students’ willingness to report threats on campus. Further, delinquency was found to be negatively associated with willingness to report, and no significant associations were found between willingness to report and demographic characteristics (gender, race/ethnicity, class status, or residence). However, like the omission in the study by Hollister et al. (2017), Sulkowski also overlooked students’ awareness of how to report safety issues. Lastly, the study by Thompson et al. (2007) surveyed 492 female university students to investigate predictors of reporting victimization to the police. Of the 141 women who had experienced sexual victimization, only two reported to the police, and among the 135 who had experienced physical victimization, only three reported to the police. The most popular reason for not reporting sexual and physical victimization was that the incident did not seem serious enough. After that, for sexual victimization, the most popular reasons for not reporting were they did not want anyone to know, and they did not want the police involved. Further, for physical victimization, victims did not want the police involved and did not want the offender to get in trouble. A noteworthy assertion in this study was that women typically do not report their victimization to the police, and the authors opined that “the finding that many women did not report the incident to the police because they did not think it was serious enough suggests that college women need to be educated about what constitutes violence and how the legal code defines certain victimizing behaviors as crimes” (Thompson et al., 2007, p.281). That is, women may benefit from campus safety educational initiatives designed to increase awareness of what constitutes violence on campus. Thus, based on literature, campus safety reporting is an important aspect of campus safety, yet, scholars tend to overlook the extent to which their student-respondents were aware of how to report safety issues. Awareness of Campus Emergency Reporting (ACER). Literature appears to indicate the existence of structural differences in which members of the campus community choose to report a crime to campus authorities. Scholars have taken interest in this decision to report campus safety issues, but many of these studies overlooked the potential impact of student awareness (of campus safety reporting procedures) on the student's decision to report. For example, some studies have investigated many potential factors of the reporting decision among university students such as negative perceptions of police (Hollister et al., 2017), how connected students are to campus (Sulkowski, 2011), or not knowing who to turn to for help (Buhi, Clayton, & Surrency, 2009). While the studies mentioned in the last paragraph do contribute significantly to the general understanding of the reporting decision, none of them offer insight into whether university students are aware of how to report an issue to authorities. A key assumption of many of these studies is that students are already aware of how to report campus safety issues when they arise, but that they choose not to report for other socio-psychological and environmental reasons (Buhi, Clayton, & Surrency, 2009; Hollister et al., 2017; Sulkowski, 2011; Thompson et al., 2007). Thus, based on the literature search, it is unclear whether a lack of student-awareness of reporting methods may be exerting an influence on the decision to report campus safety issues to campus authorities.Arguably, one logical assumption about the likelihood of reporting campus safety issues is that students are not well educated about the different types of emergencies that the campus safety department is capable of addressing. If this is true, students, who typically are not as informed as the faculty and the administration about departmental functions, may fail to report an emergency simply because they are unsure whether a given situation can be addressed by their campus safety officials. It may, perhaps, be intuitive for students to understand that they can report certain threats such as active shooters or other criminal activity, but it is arguably less likely that they would report other types of threats, such as mental health crises, chemical spills, or exposed power lines. If students are generally unaware of which safety issues can be addressed by the campus safety department, they may be less likely to report certain threats. Without timely reports by students, of campus safety issues that arise, the response of campus safety departments may be delayed, and, as a result, the effectiveness of their response may be negatively impacted. Thus, the extent to which students are well aware of the various methods for reporting emergencies on campus, is the extent to which students are capable of providing useful, real-time information to their respective campus safety departments.Awareness of Active Emergency Response Services (AAERS). An active emergency situation can describe a wide range of emergencies that university campus safety departments must address, such as active shooters, assaults, mental health crises, weather emergencies, and other environmental emergencies. Of special interest relative to this study is the role of the emergency notification system to students’ awareness of safety services. This emergency notification system is rooted in the Clery Act that requires campus safety departments to make timely reports on campus safety status to the campus community.Emergency Notification Systems. Literature appears to suggest the existence of structural disparities in awareness and utilization of Emergency Notification Systems in the campus community. First, perhaps due to the contrasting structural demands and expectations between students who come to campus to learn, and the faculty/staff who help deliver the learning experience, there is a noteworthy disparity in awareness of Emergency Notification Systems between students and faculty/staff. On a positive note, Elsass, McKenna, and Schildkraut (2016) suggest that approximately 98 percent of faculty/staff were aware of the existence of the emergency notification services offered by their universities. Similarly, Schildkraut, McKenna, and Elsass (2017) indicate that over 95 percent of university students in their survey were aware of the existence of these emergency notification services. Therefore, a vast majority of the campus community - both students and faculty/staff – seem to be aware of the existence of these services. Schildkraut, McKenna, and Elsass (2017), however, also found that an underwhelming 49 percent of students were aware of how to enroll in emergency notification services, whereas, Elsass, McKenna, and Schildkraut (2016) found that 85 percent of faculty and staff were aware of how to enroll in the notification systems. This highlights a considerable gap in awareness of how to enroll in these systems between students (49 percent) and faculty/staff (85 percent). Given that faculty/staff appear to report higher levels of awareness (relative to students) regarding these emergency notification systems, further investigation is warranted into the structural predictors of awareness among students. Lastly, students report that they are largely aware of the existence of emergency notification services (95 percent), however, less than half of student-respondents (49 percent) are aware of how to enroll in these services. Awareness of the existence of emergency notification systems is important, but if students lack awareness of how to enroll in these systems, the effectiveness of these systems is likely to be reduced, thus, the student population may benefit from improved awareness outcomes. Given the importance of emergency notifications to maintaining a safe environment for campus communities, the disparities in community awareness should not be overlooked by scholars and university administrators. Non-Emergency ServicesAwareness of Preparedness Services (APS). Campus safety officials are tasked with updating and implementing campus emergency plans and procedures to increase the overall level of preparedness to address campus emergencies. Although it is important for campus safety departments to actively respond to emergencies as they occur, there are proactive measures that can be taken to help mitigate the impact of emergencies on campus when they arise. Campus safety departments work to ensure that students are aware of potential threats to the community by publishing campus crime logs and administering other educational initiatives. However, if the campus community lacks awareness of these crime logs and educational initiatives, it is less likely to utilize the information, and thus, is less equipped to reduce its likelihood of victimization. Campus Crime Logs. In line with the spirit of transparency and accountability promoted by the Clery Act, US universities are required to track and compulsorily report campus crime statistics. These crime reports offer pertinent, up-to-date information which can be utilized to make informed decisions regarding campus safety. Arguably, if the campus community is not aware of these crime reports, members would lack the opportunity to equip themselves with vital data that could potentially reduce their likelihood of victimization on campus. Consistently with this position, literature suggests a lack of awareness and utilization of campus crime reports among university students. For example, a national study by Janosik and Gehring (2003) found that the majority of university students were unaware of the campus safety and security measures prescribed by the Clery Act and did not utilize the campus crime information provided by their institutions. This suggests that there is still work to be done to improve the level of student awareness of these campus crime logs to potentially reduce the likelihood of victimization on campus.

2. Objective

- This research is designed to investigate university students’ awareness of the campus safety services and educational initiatives made available to them. The primary objective of this study is to understand the extent to which students are aware of campus safety services and initiatives at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, the home campus of the authors, as an exploratory study. Though the literature search located studies which addressed university student awareness of campus safety services and initiatives, actual extents of students’ awareness of these services appear to be missing in those studies, thereby necessitating the need for this study to contribute to knowledge on the likelihood of awareness of campus safety services by students.

2.1. Rationale for Study Objectives

- This study is anchored by a core assumption that gaining more insight into students’ awareness of campus safety services may allow researchers and university administrators to better address university campus safety needs. When campus communities are well-aware of safety procedures and educational initiatives, they would, arguably, be better equipped to avoid victimization as well as effectively collaborate with campus safety departments in their efforts to ensure campus safety. For example, if students are aware of the various ways to report crimes on campus, they may be more likely to report crimes to safety officials. Some studies (Buhi, Clayton, & Surrency, 2009; Hollister et al., 2017; Sulkowski, 2011; Thompson et al., 2007) have investigated the decision to report campus safety issues, however, these studies do not investigate the extent to which community awareness of reporting methods might impact the decision to report. Further, if students are aware of (and participating in) campus emergency notification systems and campus crime logs, they may be more likely to take meaningful action to avoid potential victimization on campus. If community awareness is a significant antecedent of campus safety outcomes, (such as utilization of campus safety services) administrators and researchers alike may benefit from the inclusion of community awareness in their analyses of campus safety outcomes. The literature suggests that the campus community’s involvement in campus safety services and initiatives is beneficial to members of the community, and if the community is unaware of the services and initiatives, it will be unable to participate in these beneficial collaborations. According to Astor et al. (2005, p, 31), “a program that is adapted to the needs of the individual school and involves the entire school community is the most likely to be successful.” Thus, facilitating awareness and subsequent collaborations between the campus community and the Department of Campus Safety2 allows for an effective design and re-design of campus safety infrastructures.It is important for all members of the campus community (faculty, staff, and students) to be aware of general campus safety. However, in the present study we elected to focus on student awareness in particular, given the challenges unique to educating students about campus safety, coupled with the fact that students make up the majority of the campus population. We assume that the faculty and staff tend to maintain their employments with the university for a longer tenure than the typical student enrolled in a four-year degree program. As cohorts of students enter and exit the university every year, faculty and staff generally stay. Therefore, the Department of Campus Safety is tasked with orienting new students every year. As students come and go, Faculty and Staff remain on campus and accumulate more knowledge of these services and initiatives as time goes on. Thus, faculty and staff may benefit from the institutional memory associated with longer tenure on campus compared to the much more transitory and oscillating characteristics of students’ status. As such, we elected to investigate student’s tenure on campus for its potential impact on awareness of safety services and initiatives. Based on knowledge gained through our literature review, we categorized campus safety services and initiative variables into two major types: Emergency and Non-Emergency Services. Under the umbrella of emergency, we investigated Awareness of Campus Emergency Reporting (ACER) and Awareness of Active Emergency Response Services (AAERS). And, under the umbrella of non-emergency, we investigated Awareness of Preparedness Services (APS) and other non-emergency services offered by the University of Nebraska, Omaha. In addition to the variables identified in the literature search, we also investigated student awareness of campus-specific initiatives offered by the University of Nebraska, Omaha. These include Personal Safety Assistance Services and Campus Escort Services. We selected these services for investigation as we deduced from logical reasoning that they were most relevant to the needs of the university, and that they also appeared to lack any robust body of literature at this time. There is a high volume of traffic on and around the campus. This increases the likelihood of auto collisions, traffic congestion, and other maintenance related issues such as flat tires and dead batteries on campus. As many students commute to the campus on daily basis, these traffic-related activities pose a large threat to the students. As such, the Department of Campus Safety must be capable of assisting motorists with miscellaneous maintenance needs and traffic control services. In addition, the Department of Campus Safety may also be called upon to escort students, faculty, and/or staff to and from parking areas, and between buildings on campus. Given these circumstances, we decided to investigate the extent to which students were aware of the Campus Escort Services and Personal Safety Assistance Services available to them, in addition to the other variables previously discussed in the literature search. Based on literature and the general objective of this study, our primary research question is: To what extent are students at the University of Nebraska, Omaha aware of campus safety services and educational initiatives offered by their campus safety department? The scope of this study is limited to current graduate and undergraduate students who have enrolled at the university for at least two semesters, regardless of whether the two semesters were consecutive or not. Other members of the campus community, such as the members of the faculty, the administration, and other staff were excluded in the unit of analysis.

3. Design and Methods

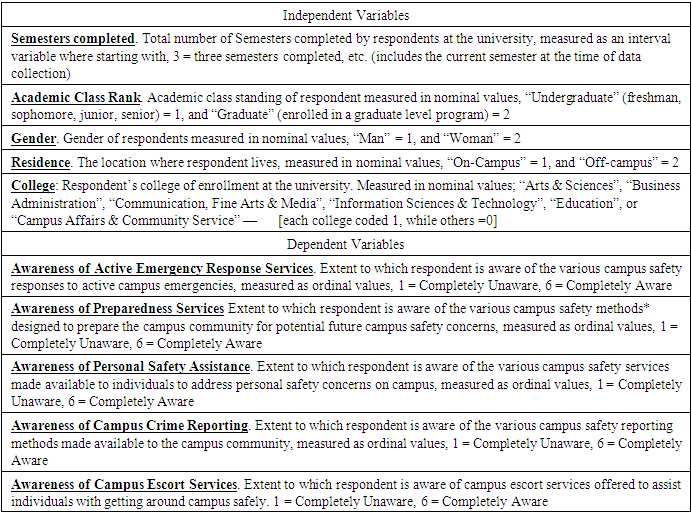

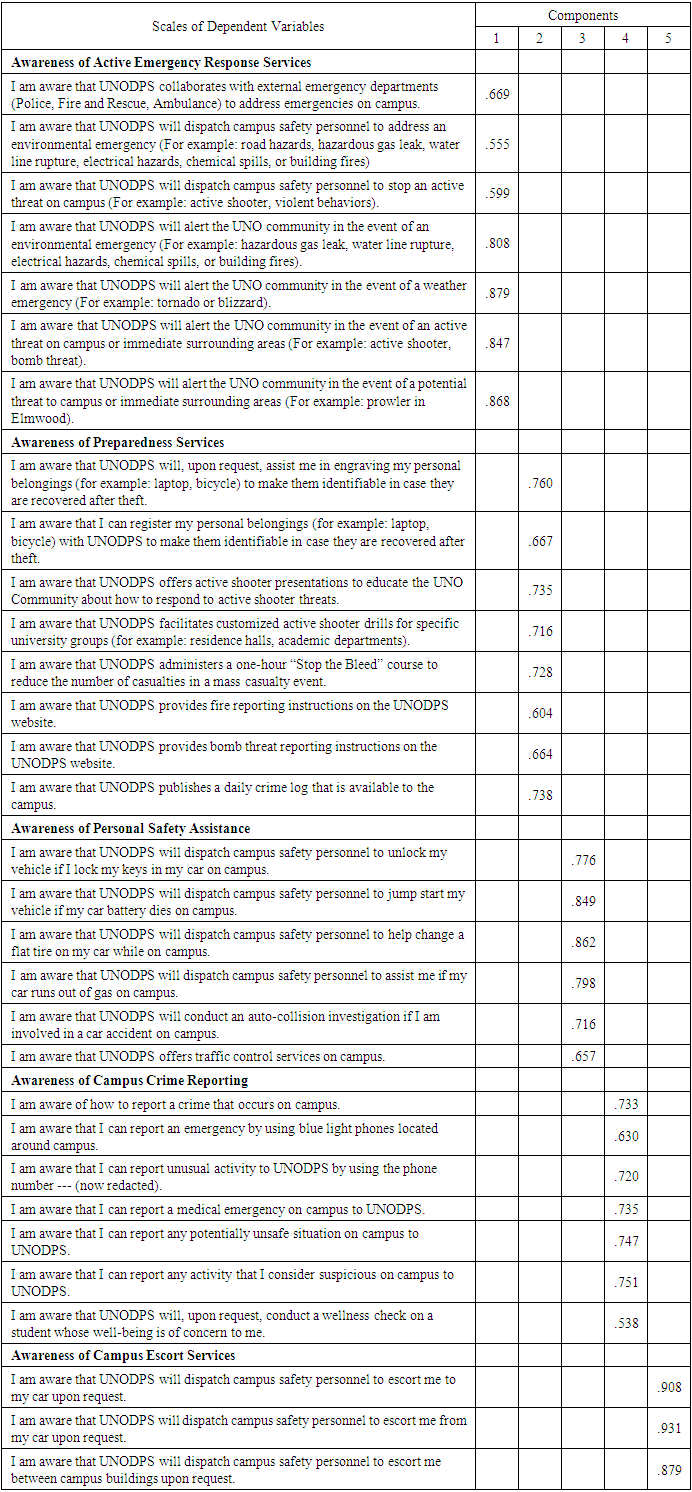

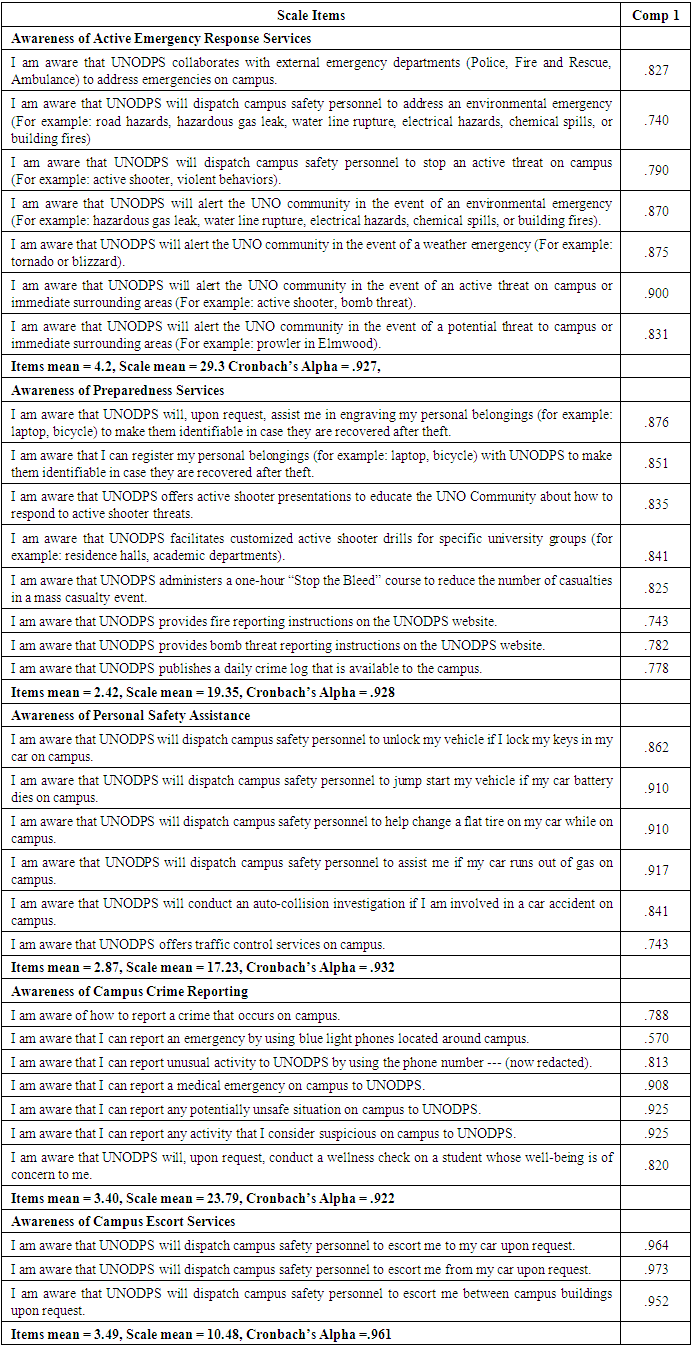

- This study was designed to use primary data since no established secondary data that fully met the needs of this study were available for analysis. A questionnaire was constructed for an electronic survey of the student body at the University of Nebraska, Omaha. The questionnaire contained demographic questions (academic class rank, gender, college of enrolment, semesters completed, residence) and scales for measuring student awareness of various campus safety services and initiatives. All variable definitions are listed in Table 1. All scales were Likert-type, six-point summated rating (Completely Aware = 6; Completely unaware = 1) and designed such that higher scores represented greater awareness of each variant of awareness. Participants were recruited through an online survey in March 2020 with the aid of the Qualtrics software, and the convenience sampling method was used due to the lack of access to information necessary for random selection. Of the 182 total responses obtained from the student body, only 90 responses were sufficiently completed to be useful for analysis. Only students who were at least 19 years old (IRB conformity requirement to avoid obtaining parental consent) and had completed at least two semesters of coursework at the university were solicited to participate in this study. We deemed the completion of at least two semesters of coursework necessary to be able to give knowledgeable responses to the questions concerning awareness of campus safety services and initiatives.

|

|

|

4. Tests and Findings

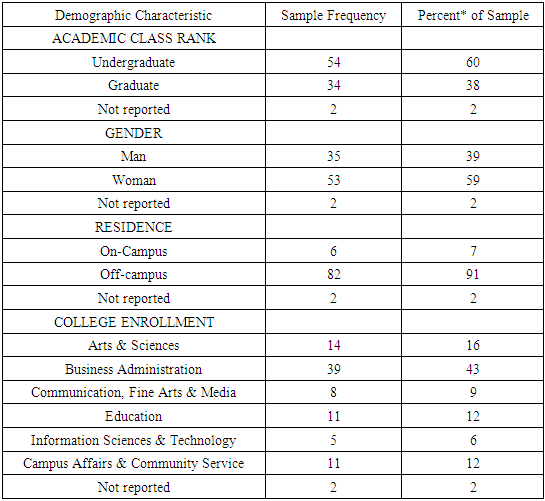

- The demographic characteristics of the 90 students in our final sample revealed that 60 percent (N = 54) of them were lower class students by academic class rank (undergraduate), and they were predominantly women (59 percent, N = 53). In addition, the students were mostly commuters as 91 percent of them resided off-campus (N = 82). Each of the six colleges in the university was also represented in the sample (see Table 4 for full sample descriptions). Test findings for all inferential analyses are presented below under each dependent variable (variants of awareness services).

|

4.1. ANOVA Tests

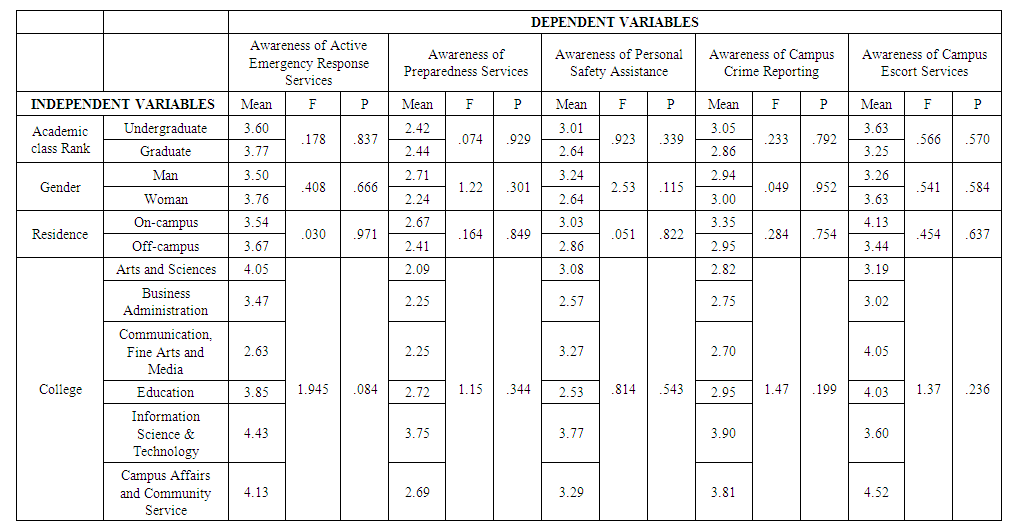

- Awareness of Active Emergency Response Services (AAERS)The ANOVA tests showed AAERS was not significantly different by the values of any of the independent variables: Academic Class Rank (p = .837), gender (p = .666), residence (P = .971), college (P = .084) See Table 5 for details of results.Awareness of Preparedness Services (APS)The ANOVA tests showed that APS was not significantly different by the values of any of the independent variables: Academic Class Rank (p = .929), gender (p = .301), residence (p = .849), college (p = .344) See Table 5 for details of results.Awareness of Personal Safety Assistance (APSA) The ANOVA tests, like our previous analysis also showed that APSA was not significantly differentiated by any of our independent variables: Academic class rank (p = .339), gender (p = .115), residence (p = .822), college (p = .543). See Table 5 for details of results.Awareness of Campus Emergency Reporting (ACER)Our ANOVA tests also failed to show that ACER was statistically different by any of our dependent variables: Academic class rank (p = .792), gender (p = .952), residence (p = .754), college (P = .199). See Table 5 for details of results.Awareness of Campus Escort Services (ACES)Similarly, to our previous ANOVA tests, our dependent variable, ACES, was not differently impacted by our independent variables: Academic class rank (p = .570), gender (p = .584), residence (p = .637), college (p = .236). See Table 5 for details of results.

| Table 5. Results of ANOVA tests |

4.2. Regression Test

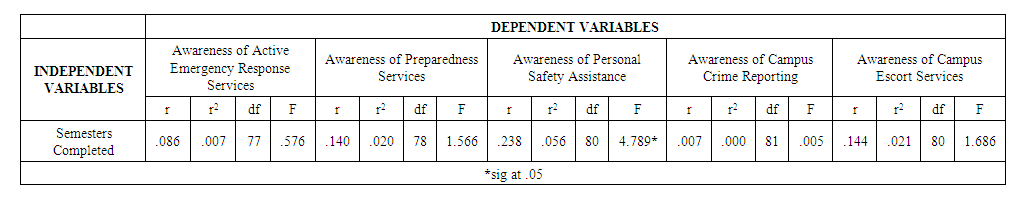

- The regression test was run to analyze the extent to which the number of semesters completed on campus predicted the likelihood of awareness of each of the awareness services (dependent variables) provided by the university’s campus security department. Test findings showed that the number semesters completed significantly predicted the likelihood of awareness of personal safety assistance services (APSA) (r = .234, r2 = .056, F = 4.789, p < .05). However, number of semesters completed did not predict the likelihood of awareness of any of the other safety services (see table 6 for details of regression results).

| Table 6. Results of regression tests |

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- This study investigated the extent to which students at the University of Nebraska, Omaha, were aware of the various campus safety services and educational initiatives offered by the Department of Campus Safety. Due to the positive impact of increased community awareness of campus safety issues on campus safety outcomes, it would behoove university administrators and campus safety departments to emphasize improved student awareness about campus safety issues.Some studies (Buhi, Clayton, & Surrency, 2009; Hollister et al., 2017; Sulkowski, 2011) have investigated the decision to report crimes on university campuses, but they have largely overlooked the extent to which students are aware of how to report campus safety issues to campus authorities. We assert that failing to assess student awareness of crime reporting procedures may result in faulty conclusions about why students behave in a given way, in terms of the crime reporting decision. That is, students may not be aware of how to report a crime even if they feel inclined to do so. As prescribed by the Clery Act, the Department of Campus Safety tracks and publishes campus crime logs to make the campus community more aware of campus safety issues. However, in order for the campus community to benefit from these crime reports, it must first be aware that these reports exist and understands how to access and utilize the reports. If the campus community lacks awareness of these crime logs, it loses the opportunity to utilize this resource to educate its members and decrease its likelihood of victimization on campus. A national study by Janosik and Gehring (2003) found that a majority of university students are unaware of the campus safety and security measures prescribed by the Clery Act and do not use the campus crime information provided by their institutions. Similarly, a study by Chekwa, Thomas, and Jones (2013) found that none of the university students surveyed was able to list campus safety legislations with which students were expected to be familiar, and only one student listed a crime and/or support resource (security officers) available on his/her campus.In this current study, students responded to the statement: “I am aware that UNODPS publishes a daily crime log that is available to the campus.” Similar to the findings of Janosik and Gehring (2003), we found that a majority of students (55%) reported that they were “completely unaware” of the daily crime log offered by the Department of Campus Safety. Albeit not statistically significant, our findings appear to suggest that students largely lack awareness of the campus safety initiatives prescribed by the Clery Act. In general, despite not being statistically significantly established, the results of our study seem to support the findings in the literature that university students tend to lack awareness regarding campus safety. The literature suggests an awareness gap exists between faculty/staff and students (Elsass, McKenna, & Schildkraut, 2016; Schildkraut, McKenna, & Elsass, 2017). Though the current study did not assess faculty/staff awareness of campus safety issues, future research should include faculty/staff respondents to better understand if this awareness gap between students and faculty/staff persists. It is possible that campus safety knowledge is accumulated over the years by faculty and staff who remain on campus, while students have limited time on campus, which may make it difficult for students to accumulate long-term safety knowledge like campus officials. This would suggest the need for a more targeted campus safety awareness educational initiative to reinforce safety information for students.A study by Schildkraut, McKenna, and Elsass (2017) found that 95 percent of students were aware of the existence of emergency notification systems provided by their university. However, these scholars also found that an underwhelming 49 percent of students were aware how to enroll in these emergency notification services. Therefore, the literature suggests that a considerable gap exists between community awareness of the existence of emergency notification services, and awareness of how to actually enroll in these emergency notification services. In the current study, students responded to the statement: “I am aware that I can opt-in to campus safety text alerts by texting” to a specified safety alert number. Only 25 percent of respondents indicated that they were “completely aware” of how to enroll in these emergency text alerts, suggesting there is much room for improvement of how to enroll in the emergency notification system. To our surprise, the analysis indicated that gender was not a significant predictor of any dependent variable in this study. Given the fact that women are victimized at a higher rate than men on university campuses (Thompson et al., 2007), we expected to see a significant difference in at least one of the dependent variables by gender. Assuming this finding was not the result of sampling error, the lack of significant differences in awareness of campus safety by gender may suggest that, on this particular campus, both men and women have received adequate safety information as well as use this information to a similar degree. It may also indicate that neither gender, especially women, felt a greater need for safety awareness information than the other.Residence status was also not a significant predictor of any dependent variable in this study. We expected that students who resided on campus might have more opportunities to be exposed to the information provided by the Department of Campus Safety, and therefore, would have a significantly greater degree of awareness regarding campus safety services and initiatives than their commuter student counterparts. This may suggest that, despite spending significantly more time on campus, students who reside on campus may not necessarily have more exposure to the information offered by the Department of Campus Safety than do commuter students. Thus, the Department of Campus Safety appears to be educating these student populations similarly, regardless of their residence locations. We explored the likelihood that the colleges in which students enrolled might influence the likelihood of awareness of campus safety services based on the logic that the type of degree programs offered by a college, and/or a college’s propinquity to the campus safety department may shape the likelihood of awareness of safety services. For example, the College of Public Affairs and Community Service houses the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, which focuses on an area of knowledge that is related to campus safety. We entertained the likelihood that students who were interested in criminal justice might also be interested in issues of campus safety, and they might, therefore, be more likely to be aware of the services and educational initiatives offered by the Department of Campus Safety. Further, we also assumed that students in the College of Arts and Sciences, which was located near the Department of Campus Safety, might be more aware of safety services than students in other colleges, such as the College of Business, that was located far from the campus safety office. However, our results did not support this assumption, thereby suggesting that students across the university had similar exposure to campus safety information, regardless of the college in which their degree programs were located. Academic class ranks were included in our analysis due to our assumption that graduate students might have spent more time on campus, and hence, might have had more exposure to safety information offered by the Department of Campus Safety. However, our analysis also failed to support this assumption. Perhaps this is because it is common for graduate students to come from other universities, and, therefore, many of them in our sample might have not had significantly more exposure to campus safety awareness information than our undergraduate students. Our analysis did not control for the influence of change of schools for graduate education because we did not collect data on this statistic, but it is worth further considerations in future research. One major finding in this study is that, despite the fact that academic class rank is not a significant predictor of any of the dependent variables, student tenure on campus, in terms of semesters completed, was a statistically significant predictor of student Awareness of Personal Safety Assistance. A regression analysis showed that the effect of Semesters Completed on APSA was statistically significant at the .05 level (r2 = .056; F = 4.789), indicating that the amount of time a student had spent at the university accounted for almost six (specifically, 5.6) percent of the variance in student awareness of personal safety assistance services. However, student tenure was not a significant predictor of the other four dependent variables. This means that the amount of time spent on campus appears to increase the likelihood of student awareness of personal safety services such as traffic control and help with basic vehicle maintenance (e.g., changing flat tires, jump-starting dead batteries), but does not appear to increase student awareness of the other important services and initiatives considered in this study. This could be due to the fact that the university is primarily a commuter campus and students mostly pay close attention to safety services that are most relevant to their needs as commuters. Episodic emergencies (e.g., fire, active shooter, weather emergencies) are relatively rare occurrences on campus, thus preparing for and addressing these situations may be a low priority for students compared to frequently occurring issues that may readily impact students’ lives. Lastly, as earlier mentioned, literature suggests that improved community awareness leads to improved campus safety outcomes and increased community participation in campus safety initiatives (crime reporting, designing campus safety infrastructures, etc.). If students are generally unaware of campus safety initiatives offered by their campus safety departments, it would behoove university safety officials to expand their outreach efforts to increase the extent to which the campus community is aware of available safety initiatives. Doing so will likely also allow for better collaboration between the campus safety departments and the campus community, and it may facilitate higher likelihood that individuals would make informed decisions that reduce their likelihood of victimization on university campuses.

6. Limitations

- A limitation exists in the ability to use the findings of this study to make generalizations about awareness of students regarding campus safety on university campuses. First, we utilized a convenience sampling method due to the logistical challenges associated with obtaining a random sample from the university and administering the survey remotely to the student population. As a result of the non-random sampling method, the sample used was not representative of the entire student population at the university. For a reliable generalization to be made, a representative sample of the student population is required. Second, our sample is slightly smaller than we would have expected, given the 182 responses obtained. Only 90 responses were useful for analysis after removing outliers and incomplete responses that were submitted. Given the outlined limitation of this study, caution is encouraged while any making generalization from its findings. As true of any nonrandom sample, the findings of this study would be most accurate when limited to the study participants. Future research is encouraged to employ random sampling methods as well as use a larger sample size to improve the generalizability of findings. We also recommend future studies to consider the level of awareness of the campus community before attempting to assess campus safety outcomes such as the decision to report crimes, and the utilization of emergency notification systems. Once researchers and administrators understand the baseline level of community awareness, they can make strategically sound decisions about how to design and implement campus safety services and initiatives.

Notes

- 1. This project was a continuation of an applied class project which started in the senior/graduate level course in applied formal organizations taught by the third author. The first two authors were graduate and undergraduate students, respectively, in the class, and they have led this project under the supervision of the third author and mentor.2. The Department of Campus Safety is used in this study, instead of the “Department of Public Safety” used by the university, to prevent any confusion with the Omaha city police that is also officially recognized as a public safety agency.

Conflict of Interest and Funding

- The authors declare no Conflict of Interest or Funding of any sort in the conduct and preparation of this research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML