Naing Kyi Win1, Nyein Nyein Htwe2, Cho Cho San3, Kyaw Kyaw Win4

1P.h.D. candidate, Agricultural Extension, Yezin Agricultural University, Zeyarthiri, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar

2Professor, Agricultural Extension, Yezin Agricultural University, Zeyarthiri, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar

3Professor, Agricultural Economics, Yezin Agricultural University, Zeyarthiri, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar

4Pro Rector, Yezin Agricultural University, Zeyarthiri, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar

Correspondence to: Naing Kyi Win, P.h.D. candidate, Agricultural Extension, Yezin Agricultural University, Zeyarthiri, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Agriculture in Myanmar, dominated by paddy rice cultivation, generates a direct or indirect economic livelihood for over 75% of the population. Hybrid rice development in Myanmar has been hampered by several nontrivial scientific and technical challenges. So far, hybrid rice has had limited impact in Myanmar. Hybrid rice is a very new seed industry which is pushing hard for hybrid rice’s success. Therefore, research was conducted to determine the influential factors contributing to rice seed producers’ attitudes to hybrid rice seed production in the Nay Pyi Taw area, Myanmar. Objectives of the study were: 1) to study the characteristics of the rice seed producers, and their performance in seed production; 2) to find out hybrid rice seed producers’ perceptions regarding rice seed sector development; 3) to determine the factors influencing change in the hybrid rice seed production development in Myanmar. A total of 54 respondents (13 hybrid rice seed producers and 41 inbred rice seed growers) in Nay Pyi Taw were interviewed between October and December 2017 using structural questionnaires and analyzed by descriptive statistics and the Rensis Likert (1932) scale using 5 points to measure attitudes to seed production. The study revealed that among the 41 respondents producing inbred rice seed (39 male and 2 female) the average age was 45 years, ranging from a minimum of 36 years to a maximum of 58 years. Average farm size was 4.1 ha, most growers have formal education (19.5% of were graduates) and 92.7% had rice seed production experience. Almost all, 97.6%, had 1 to 5 year’s seed production experience and 92.7% used their own land. Only 14.6% of seed growers had adopted mechanized farming. Among the13 respondents producing hybrid rice seed (10 male and 3 female) and the average age was 43.7 years, ranging from a minimum of 33 years to a maximum age of 52 years. Almost, 12 out of 13 respondents possessed a Diploma or Bachelor Degree related to agriculture. All respondents had received technical training and had 6 to 10 years’ experience. Among important factors for inbred rice seed producers, the majority (95.1%) stated the need to “register seeds” and 83% and 87.8% respondents considered “labor scarcity” and “skill labor” to be most important. Also, 78.1% and 87.8% of seed grower farmers identified “high cost of production” and to “roguing difficulties” as important or most important factors, while 51.2% and 41.5% of seed growers identified “difficulties of transplanting” and “water problem” as important or most important. In contrast to inbred seed producers, hybrid rice seed producers universally considered obtaining parental lines and “rouging” as most important, while 84.7% and 92.3% faced “water problem” and “weed, pest and disease problem”. Additionally, 92.3% of seed producers mentioned “difficulties of transplanting” and 61.5% and 92.3% identified “labor scarcity” and “skilled labor scarcity” as important or most important problems. A large majority, 92.3% and 84.7%, considered “farm machinery availability” and “high cost of production” as important or most important. Furthermore, 84.6% of respondents faced a “synchronization problem” as important and important because of climate change and technical weakness. More than half of respondents complained of cost and availability to buy GA3 from China, and 69.3% of respondents used insufficient quality. Hybrid seed producers identified “chemicals cost and availability” as important or most important, while 30.8% paid attention to “synchronization” and considered “spending too much time in field” as important. Several major influential factors were behind the change from inbred rice to hybrid rice seed production. The majority (96.3%) of seed producers agreed to “extension agents” as the main information source, while 85.3% mentioned “technical training”. More than half of respondents pointed out the “seed business market” as most important or important, while 51.8% identified “water availability” as important or most important. As a result, this study recommends additional research and advanced breeding for hybrid rice, a stronger extension strategy, establishment of seed production zones with sufficient water, introduction of contract seed production, access to credit and a good input delivery system, fully mechanized seed production, partnership between the public and the private sector for hybrid rice seed production, and a well-designed seed policy with provision of hybrid rice seeds and hybrid rice promotion.

Keywords:

Hybrid rice, Seed production, Influential factors, Attitude change

Cite this paper: Naing Kyi Win, Nyein Nyein Htwe, Cho Cho San, Kyaw Kyaw Win, Rice Seed Producers’ Attitudes to Hybrid Rice Seed Production in Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, International Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-9. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20190901.01.

1. Introduction

In Myanmar, the agriculture sector is the largest contributor to the national economy, contributing 28.6% of GDP and 25.5% of total export earnings in 2015-16 and employing 61.2% of the labor force [1]. The ultimate goal of the rice sector strategy is a food-secure nation where small holder farmers have tripled their household income, including income derived from rice and rice-based farming, thereby achieving a decent standard of living comparable to that of urban dwellers [2].

2. History of Rice Production in Myanmar

Agriculture in Myanmar is dominated by paddy rice cultivation and generates a direct or indirect economic livelihood for over 75% of the population. Rice is grown throughout the country by resource-poor rural farmers and landless agricultural laborers on small farms averaging only 2.3 ha in size [3]. Myanmar has a long tradition of rice production. In the years immediately prior to World War II it was the largest rice-producing nation in the world, and it continues to be one of the ten largest rice-producing countries [4]. With the Green Revolution in 1966, the switch to high yield production techniques by the use of high yielding plant material combined with the application of fertilizers was recognized and accepted. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the government-sponsored Whole Township Paddy Production Program introduced modern high yielding varieties (HYVs) of rice and thereby enhanced production possibilities. Since that time over 60 HYVs, usually of the semi-dwarf type, have been introduced, and now account for 70% of the total area planted to lowland rice [5]. Many of these varieties can accommodate closer spacing, heavy nitrogen (N) fertilization, continuous cropping and/or are photoperiod insensitive. Overall, this adaptation of HYVs and the improvement of irrigation systems in some areas of the country has allowed for the cultivation of rice in the dry summer season and for double cropping. In particular, IR 50 and IR 13240-108-2-2-3 now occupy 80% of the country’s post-monsoon rice cultivated area [6]. Nonetheless, despite the cultivation of HYVs in many parts of the country, the expected increases in yield were not achieved [4]. Rather, the average rice yield has remained relatively stagnant at 3.2 t ha-1 in 1994, 3.3 t ha-1 in 2000, and 3.4 t ha-1 in 2002 [7]. By 2016/17, the total rice planted area was 7.16 million ha, of which 6.16 million ha under monsoon paddy and 1 million ha under irrigated summer paddy [8]. According to a World Bank report published in 2016 [9], Myanmar’s average rice yield is the second lowest in Asia. This means Myanmar needs to improve varieties and technology for rice production to close the yield gap with its neighbors. The national average rice yield of 3.94 tons/ha is still low considering the potential yield that can be achieved when farmers would plant good-quality seeds of high-yielding varieties and apply improved crop management practices and application of agricultural inputs such irrigation water, agro-chemicals and natural fertilizers and promotion of machineries utilization as technology intervention.

3. Hybrid Rice Technology Development in Myanmar

Hybrid rice technology has contributed significantly toward food security, environmental protection and employment opportunities in China. Since the mid-1990s, this technology has also been developed and introduced to farmers in India, Vietnam, the Philippines, Bangladesh, and the United States, either independently or in close collaboration with the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines. Several other countries, such as Egypt, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and the Republic of Korea, as well as Myanmar, developed hybrid rice technology in collaboration with IRRI. Hybrid rice research was initiated in Myanmar in 1991 with the introduction of two cytoplasmic male sterile (CMS) lines, IR 62829A and IR 58025A, from IRRI. The first two hybrids developed in Myanmar were Yezin hybrid rice number 1, using IR62829A and Theehtatyin as parent lines, and Yezin hybrid rice number 2 using IR62829A and Shwetweyin as parent lines. However, the yield advantage of these first two hybrids was not significant compared to existing inbred varieties [10]. Some promising hybrids were evaluated in irrigated areas during the monsoon and dry seasons with the support of FAO under “Strengthening the development and use of hybrid rice with the fund of Technical Cooperative Program (TCP)” project in 1997. The introduction of parental lines from China, and production of hybrid seeds using Chinese with assistance of Chinese technicians, with strong regional government support led to successful introduction in Shan State in northern Myanmar [11]. Problems persisted, however, particularly in regard to a lack of knowledge in disease control, especially bacterial leaf blight (BLB) and bacterial leaf smut (BLS), and lack of access to markets where hybrid rice is acceptable to consumers. The Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MOAI) nevertheless actively promoted the use of hybrid rice in cooperation with the Chinese Anhui Longping Hi-tech Seed Co., Ltd. In the 2011 monsoon season, the Department of Agriculture (DOA), Department of Agricultural Research (DAR), and also Yezin Agricultural University (YAU), carried out hybrid rice seed production with Chinese technicians’ guidance using Chinese parental lines. Research and development was, and continues to be, led by the public sector, but the private sector is now taking a more active role in seed production. Currently, three seed companies are producing hybrid rice seed in Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, using eight hybrid lines. Hybrid rice is grown principally in Nay Pyi Taw, Mandalay, Sagaing, Ayeyarwady and Northern Shan state.Hybrid rice development in Myanmar has been hampered by several non-trivial scientific and technical challenges. It has drawn on a narrow germplasm base that poses significant constraints on producing the marketable hybrids with yield advantages preferred by farmers and the grain qualities preferred by consumers. An additional challenge is the insignificant levels of quantity and quality hybrid rice seed production, and the need to conduct more seed production research. On the other hand, inbred HYV rice seed producers have been producing certified seed with support from a quality seed production program as an attempt to improve their competitive position and performance in relation to hybrid rice seed producers. Today, three hybrid seed companies in Myanmar are owned, either in whole or in part, by Chinese seed companies (or else closely allied to them). So far, hybrid rice has had limited impact in Myanmar. The cost of the seed is high (USD 2.40 to USD 3.00/kg), and the quality of the grain produced is poor from the perspective of consumers. Nevertheless, this is a very new seed industry which is pushing hard for hybrid rice’s "success". But already, social perceptions in Myanmar are not favorable to hybrid rice. Concerns are raised about the reliability of the planting material, the impact on genetic diversity, increased dependency of farmers on the new seed industry, along with questions about the motives of the private sector. As a result, we need to understand rice seed producers’ attitude to hybrid rice seed production and their determinants and support to future rice seed industry.The objectives of this research are therefore:1. To study the characteristics of the rice seed producers and their performance in seed production.2. To find out rice seed producers’ perceptions about rice seed sector development.3. To determine the factors influencing adoption of hybrid rice seed production in Myanmar.

4. Material and Method

This study was conducted in the Nay Pyi Taw council area, Myanmar, consisting of Pyinmanar, Lewe, Dekhinathiri, Zabuthiri, Tetkhone, Pobbathiri, Zeyathiri and Oattathiri Townships. Nay Pyi Taw is the administrative capital of the Union of Myanmar, centrally located between the two commercial cities of Yangon and Mandalay. More than 160,000 acres are used for paddy in the rainy season, but only one tenth of the area is planted t rice in the post-monsoon season. Nay Pyi Taw is a favorable area for rice seed production because of land improvements to allow mechanized farming, and irrigation water is available from 13 dams, including Chaungmagyi, Ngalaik Dam, and Yezin.Currently, there are three private seed companies operating in the study area, including Great Wall, Ayeyar Longping High-Tech Seed, and Myanmar Golden Sunland Seed. These seed companies contracted 364 hectares of hybrid rice seed 364 ha in Nay Pyi Taw with 13 hybrid rice seed producers. A total of 61 inbred rice seed grower farmers were trained and organized as seed grower farmers as an association and encouraged by Department of Agriculture. Among them, 41 seed grower farmers were selected. A total of fifty-four rice seed producers were interviewed using questionnaires administered by a personal interview between October and December in 2017. Secondary data were also collected from the Department of Agriculture divisional and township offices.Attitudes are learned or established predispositions to respond in a particular way [12]. Observed attitudes have many potential causes [13]. Attitudes are not directly observable, but actions or behaviors to which they contribute may be observed [14]. There are factors that intervene between attitude and behavior which may cause a person’s behavior to be inconsistent with his or her attitude [15]. These factors include personal characteristics, social norms and expected consequences of behavior. The following types of data were collected by the survey questionnaire to help explain actions: general information of rice seed producers (land access, machines, technology factors), information sources, advantages and disadvantages of producing hybrid seed changes of likelihood, cost and benefits, seed production protocol, post-harvest technology, quality seed and seed market, motivation, main challenges and problems encountered, perception on seed business and the factors influential change in attitudes to hybrid rice seed production. In order to achieve the objectives and measure attitude, farmer responses were analyzed by descriptive statistics and use of the Rensis Likert (1932) scale to measure attitudes of seed production [16]. The typical Likert-type scale consists of a 5 to 7-point ordinal scale used by respondents to rate the degree to which they agree or disagree with, or like or dislike, the statements presented to them. In our study, attitudes were inferred using a five-point "Likert-type" scale concerning one of five levels of "agreement": 1) "Strongly agree", 2) "Agree", 3) “Neutral”, 4) "Disagree" and 5) "Strongly disagree".

5. Results and Discussion

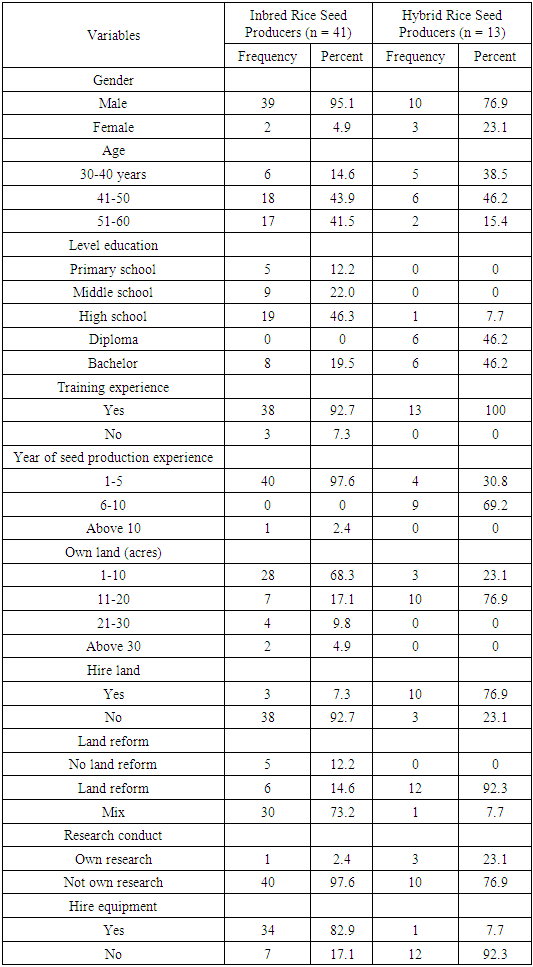

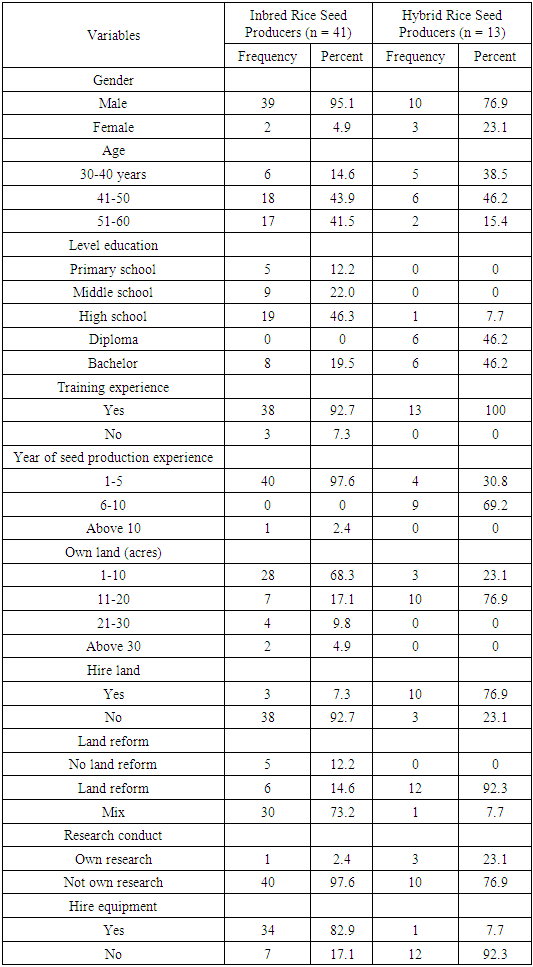

Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents: The findings revealed that, among producers of inbred rice seed, 95.1% were male and 4.9% were female. The average age of the sample seed grower was 45 years, ranging from 36 years to a maximum of 58. The average farm size in the study area was 4.1 ha. Most respondents have formal education: 19.5% of them achieved a graduate education level while 92.7% had rice seed production experience. Almost all farmers, 97.6%, had between 1 and 5 years’ seed production experience. Almost all farmers used their own land for seed production, while a few, just 7.3%, rented in land for seed production. Only 14.6% of seed growers had their land improved for mechanized farming and the majority, 85.2% hired equipment and machines from outside rental services. Only one seed producer conducted rice seed production research.Among hybrid seed producers, on the other hand, 10 out of 13 respondents were male and 3 respondents were female. The average farmer age was 43.7 years ranging from a maximum age of 52 and a minimum of 33 years. Almost all, 12 out of 13 respondents, possessed either a Diploma or a Bachelor Degree related to agriculture. All respondents already received hybrid rice technical training and had 6 to 10 years’ experience with hybrid rice seed production. The majority of hybrid seed producers (76.9%) rented in land from local farmers because they did not own sufficient land. Most of the land rented in, 92.6%, was already improved to facilitate mechanized farming. Three seed producers have conducted research related to hybrid rice seed production. The majority of hybrid rice seed producers, 92.5%, owned equipment and machinery for farming Table 1.Table 1. Demographic profiles of hybrid and inbred rice seed producers

|

| |

|

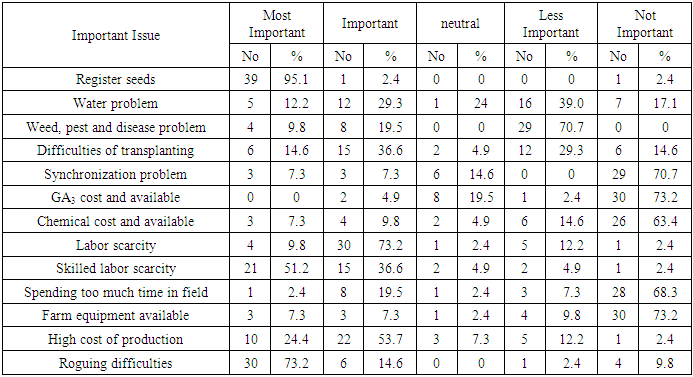

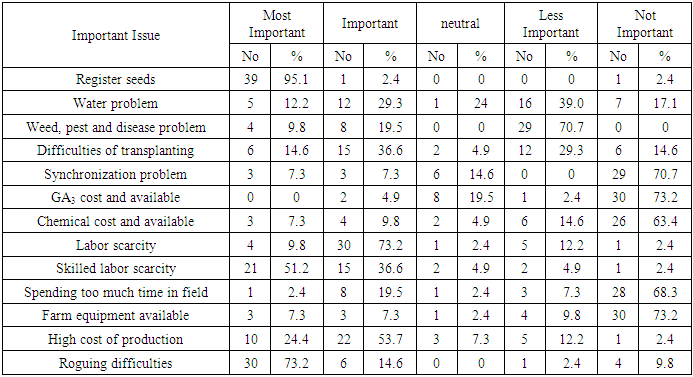

Important factors for inbred rice seed production: Table 2 presents important factors for inbred rice seed production. The majority of inbred rice seed producers, 95.1%, considered the need to “register seeds” as most important. Labor also figured highly in responses, with 83% of respondents identifying “labor scarcity” asmost important or important, while 87.8% of seed producers mentioned access to “skill labor” with these levels of ranking. Not surprisingly for a commercial activity, 78.1% of seed grower farmers pointed “high cost of production” asmost important or important. Besides, 87.8% of seed growers considered “roguing difficulties” most important and important, while 51.2% of seed growers identified “difficulties of transplanting”, and 41.5% “water problem”. A few of the respondents also complained of synchronization problem, GA3, chemical cost and availability, spending too much time in field and farm equipment available.Table 2. Important factors for inbred rice seed production

|

| |

|

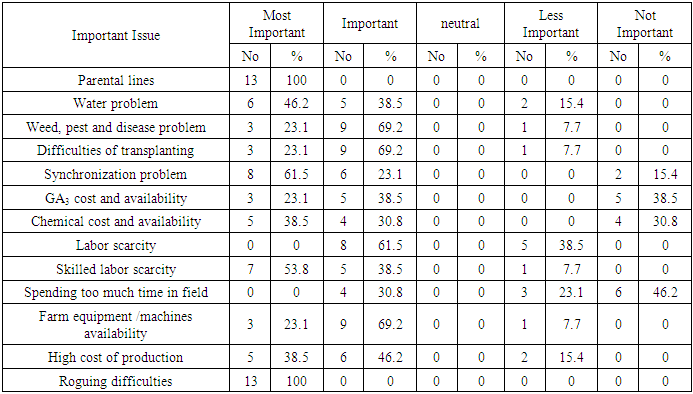

Important factors for hybrid rice seed production: Table 3 presents important factors identified by hybrid rice seed producers. All of them indicated access to parental lines and “roguing” as most important difficulties for them. Also, 84.7% of seed producers encountered “water problem”, while 92.3% identified “weed, pest and disease problem” as either most important or important. Next, 92.3% of seed producers mentioned “difficulties of transplanting”, while 61.5% and 92.3% referred to “labor scarcity or “skilled labor scarcity” as most important or important issues. The availability of farm machinery was either an important or most important concern for 92.3% of seed producers, as they had to hire outside services, and 84.7% of seed producers identified “high cost of production” due to increases in land rental rates, chemical costs and labor wages. In addition, 84.6% of respondents identified “synchronization problem” as important or most important because of climate change and technical weakness. More than half of respondents complained of the availability or cost of GA3 from China. The majority of producers, 69.3%, identified “chemicals cost and availability” as important or most important, while 30.8% of hybrid seed producers noted the importance of “synchronization” and thus “spending too much time in field”.Table 3. Important factors for Hybrid rice seed production

|

| |

|

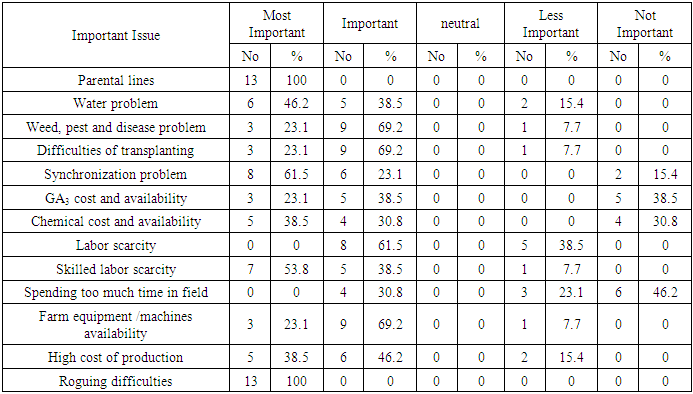

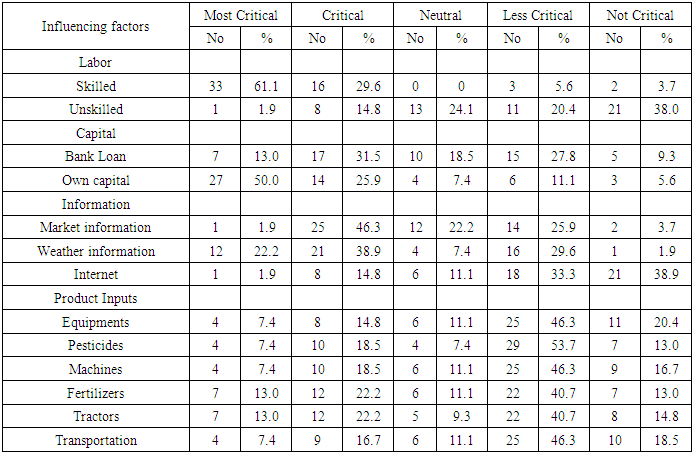

Influential factors regarding input resources for rice seed production: In table 4, 90.7% of hybrid seed producers identified access to “skilled labor” as either most critical or critical, while 75.9% of respondents rated “own capital” as most critical or critical. Access to “market information’ and “weather information” was most critical or critical for 48.2% and 61.1% of respondents, respectively. Only a few of respondents identified “production inputs”, such as equipment, pesticides, machines, fertilizers and tractors, because they can access them relatively easily. A few respondents mentioned “transportation” for inputs and products as this is generally good in the study area.Table 4. Influencing factors for inputs supply in hybrid and inbred rice seed production (n = 54)

|

| |

|

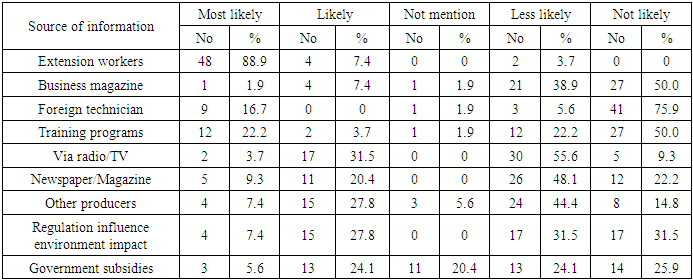

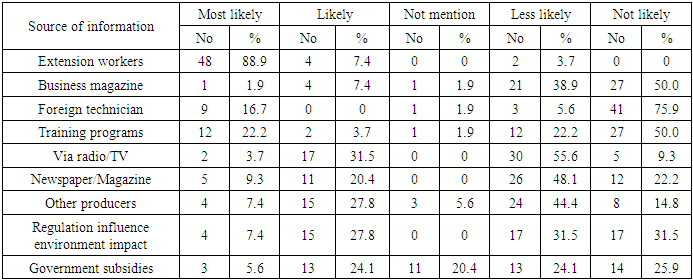

Information sources influential option of rice seed production: Table 5 presents data on different sources of information affecting the decision to adopt rice seed production as an enterprise. For 96.3% of seed producers, “extension agents” were the most influential information source because they worked closely with and assisted seed producers. A few respondents also mentioned “foreign technician” or “business magazines” as influential. One fourth of respondents identified “training programs” as an influential source of information, and most respondents see training programs as enhancing awareness of knowledge. One third of respondents agreed to “via radio/TV” and “newspaper/magazine” as important influential information sources, but it was entertainment for most of the seed producers. Over a third of respondents, 35.2%, identified “other producers” as a source of information, as well as “Regulation influence to environment impact”. Furthermore, 29.7% of respondents pointed to “Government subsidies” as important, but the majorities of respondents do not rely on these information sources but do consider Government support is not enough for their requirements.Table 5. Information sources influential adoption of hybrid and inbred rice seed production (n = 54)

|

| |

|

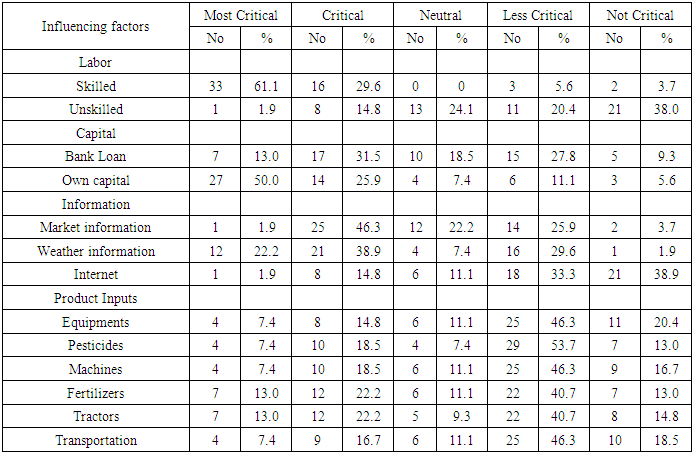

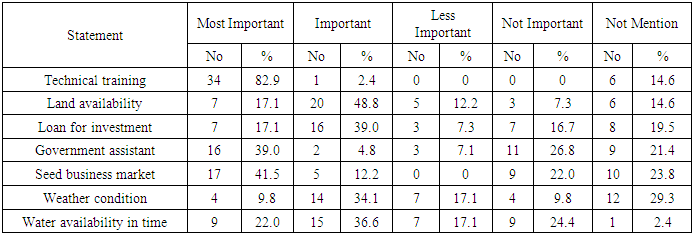

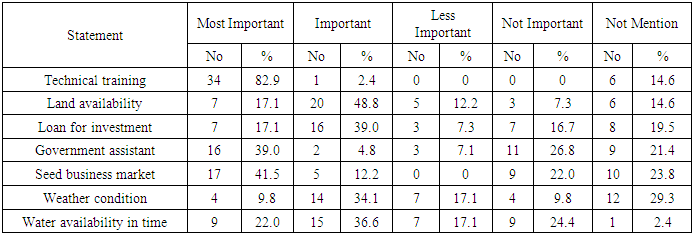

Major influential factors for changing inbred rice to hybrid rice seed production: In the case of hybrid rice seed production, table 6 shows that the majority, 85.3%, of respondents mentioned “technical training” in hybrid rice seed production asmost important or important. Besides the importance of technical training, more than half of respondents identified “land availability” as most important or important due to the high cost of land rental in the Nay Pyi Taw area. One fifth of respondents identified access to a loan as most important or important because hybrid rice seed production requires around USD 2,500 per hectare of investment. Less than half of the respondents saw assistance from Government most important or important even though Government manages the seed protocols, regulation and seed registration. In contrast, more than half of respondents pointed out “seed business market” as most important or important because seed producers sold their production commercially. Less than half of respondents identified weather as either most important or important but slightly more than half, 51.8%, of respondents identified “water availability” as most important or important because of its critical role for seedling nursery, field size, and management of for male and female rice plant synchronization at flowering time.Table 6. Major influential factors change to hybrid rice seed production from inbred rice seed production (n = 41)

|

| |

|

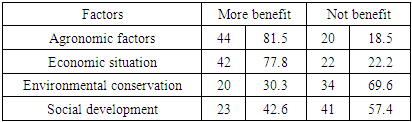

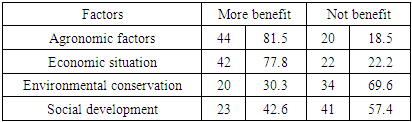

Table 7 presents the perceptions of rice seed producers on the benefits of rice seed production. A large majority, 81.5%of seed producers identified “agronomic factors” as beneficial to them, while 77.8% saw a benefit to their “economic situation”. More than half the respondents, 69.7% and 57.4%, did not see a benefit in regard to either “environmental conservation” or “social development”. Table 7. Benefits of rice seed production (n = 54)

|

| |

|

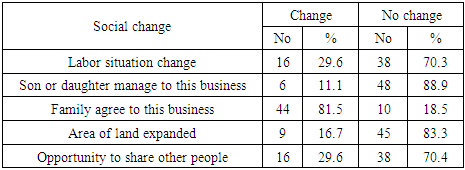

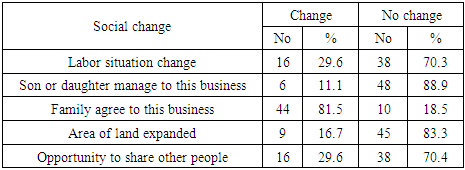

Table 8 presents information on farmer’s perception of how rice seed production changed their social condition. The majority, 70.27%, reported no changes to their labor situation. Although 81.5% of families agreed to the seed business, in 88.9% of cases no family member was directly involved. The majority of respondents (83.3%) did not expand their land for seed production, and 70.4% of respondents did not shared information about this opportunity.Table 8. Social condition changes after conducting rice seed production (n = 54)

|

| |

|

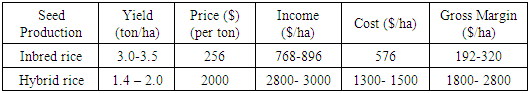

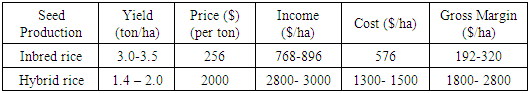

Comparison of yield and profitability of inbred and hybrid rice seed production. Table 9 presents information on costs and benefits of inbred and hybrid seed production. The yield of inbred rice seed production was 3.0 to 3.5 ton/ha, whereas hybrid rice seed production yielded 1.8 to 2.5ton/ha. Inbred rice seed producers reported gross margins of 192 to 320 $ per ha (cost to benefit ratio is 30%), whereas hybrid rice seed producers earned 1800 to 2800 $ per ha (cost to benefit ratio is 50%). For contract seed production, seed producers used 1 kg plastic bags for hybrid seed and 30 kg for inbred rice seeds. In addition to the seed company logo and contact information (address and phone number), labelling information included seed purity percent, germination percent, weight in Kg, a bar code to identify the product, expiry date, and information on rice growing techniques. Whereas companies store seeds under cold storage, seed growers store in ambient conditions. Both inbred and hybrid seed producers reported that most of the farmers preferred their seed quality because they followed the recommended procedures for seed production. The majority of rice farmers have evaluated their seed favorably in relation to germination and purity, uniformity, and high yield. They believed that their seed business was successful, improved seed markets and expanded the seed business.Table 9. Estimated Cost and Gross Margin of Rice Seed Production

|

| |

|

Rice seed producers’ perceptions of the rice seed business: Hybrid rice seed producers’ perceptions on whether seed production is a good business for the future are not well established at this point given the lack of parental lines to produce good eating quality, the need for synchronization, the high cost of hybrid seed, and vulnerability to pests and diseases. On the other hand, inbred rice seed producers’ perceptions indicate satisfaction with their seed production business and an interest to extend this business. Farmers' livelihood from seed production business, inbred and hybrid, could benefit from systematic roguing, and collaboration between farmers and technical staff advising on rice seed production.Our study found that hybrid rice seed producers have more experience than inbred rice seed producers. Positive influential factors were access to parental lines, land, water, labor, and resources for investment in hybrid rice seed production. [17] supported that hybrid rice seed production may be considered a highly labor, capital and knowledge intensive process, besides one with heavy risks from poor synchronization of parental lines, weather changes, etc. Hybrid rice seed production is highly labor-intensive which requires about 100-150 additional person days of labor per a hectare.Our study showed that extension workers were main source of information, while key input factors were access to skilled labor and investment. It was also found out that seed producers’ perception is that rice seed production is beneficial from economic and agronomic perspectives. Farmers would not be motivated to engage in hybrid rice seed production if labor is not available at a reasonable wage and unless it is shown to be more profitable than the alternative of cultivating inbred varieties (MVs). The results of this study indicate that social changes were not significant as farm and family members are not involved in seed production, although they support involvement in seed production. [18] reported as economic benefit; the intensive labor input in hybrid rice seed production has increased both rural employment opportunities and famers’ incomes. Hybrid rice technology has generated more than 100,000 jobs related to hybrid rice research, extension, and seed production, and indirectly has generated 10 million jobs in rural areas in China. Factors that positively influence producers to switch to hybrid rice seed production from inbred rice seed production were technical training, land availability, loan from banks, water availability in time, favorable weather condition. [19] Indicated that Hybrid rice seed production technology is considered labor and knowledge-intensive. It involves various risks, especially in the early stages when seed producers are still lacking in experience. Typical problems are poor synchronization of the parental lines, and unfavorable weather.Major challenges encountered by inbred seed producers were the application of chemicals and fertilizers, water, access to skilled labor and roguing for purity. Hybrid rice seed producers faced additional challenges relate to labor for roguing, spending more time for field management and encouragement and cooperation with government, high cost of land rental and the need to conduct research, high cost for seed production, past experience of hybrid rice variety not accepted by market due to the bad taste, sustainable market, trade in local and internal, seed export to foreign markets. In light of these challenges.

6. Conclusions

This study highlights the challenges encountered by commercial rice seed producers, a relatively new and still emerging segment in Myanmar. Seed producers need time to become familiar with hybrid rice seed production technologies. Moreover, there were challenges arising from consumer preferences, water availability, agro-chemicals, access to skilled laborand high cost of land rental. Furthermore, it still needs seed purity and quality, government subsides, research and extension strategies, high cost for seed production, and sustainable market. Contract farming arrangements for seed production, combined with private and public sector collaboration on extension, could encouragerice seed producers to view hybrid rice seed production more positively.In light of our findings we recommend the following measures:- Establish research and advanced breeding with close cooperation between hybrid rice researchers and hybrid rice seed companies for the exploitation of new hybrid rice varieties into commercial rice production. - Strengthen extension strategy and roles, and training for hybrid rice seed production technology.- Establish seed production zones with sufficient water.- Ensure an effective credit program for investment and good input delivery system.- Develop fully mechanized seed production systems to reduce labor requirements.- Strengthen partnership between the public and the private sector for hybrid rice seed production, including contract seed production arrangements.- Introduce a supportive seed policy in regard to the provision of hybrid rice seeds and hybrid rice promotion program.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors appreciate the willingness of seed companies and seed grower farmers for sharing their attitudes and knowledge concerning seed production. We also would like to acknowledge the support of staff from the Department of Agriculture, Nay Pyi Taw, for providing their time to assist in data collection.

References

| [1] | DOP; Myanmar Agriculture Sector in Brief, Nay Pyi Taw, Department of Planning, Ministry of Agricultural, Livestock and Irrigation (MOALI), Myanmar; 2016. |

| [2] | MOAI; Myanmar Rice Sector Development Strategy, Nay Pyi Taw, Ministry of Agricultural, and Irrigation (MOAI), Myanmar, 2015. |

| [3] | Okamoto, I.; Agricultural Marketing Reform and Rural Economy in Myanmar: The Successful Side of Reform; Paper presented at the Parallel Session II, “Reform in Agriculture-Country experiences from Asia”, GDN the 5th Conference, 28th, January 2004, New Delhi, India; 2004. |

| [4] | IRRI; Rice Almanac. Source book for the most important economic activity on earth; International Rice Research Institute, Manila, The Philippines; 2002. Nguyen, V. and Tran, D.; Rice in production countries; FAO Rice Information; 3:19–21; 2002. |

| [5] | Nguyen, V. and Tran, D.; Rice in production countries; FAO Rice Information; 3:19–1; 2002. |

| [6] | Kaushik, R.; Breeding for Resistance to Diseases and Insect Pests of Rice in Myanmar; Terminal Report, Plant Breeding, Genetics & Biochemistry Division. IRRI, Manila, The Philippines; 2001. |

| [7] | MOAI; Myanmar Agriculture in Brief; Yangon, Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MOAI), Myanmar; 2003. |

| [8] | DOA, Annual Report of Statistic Year Book, Nay Pyi Taw, Rice Division, Department of Agriculture, Ministry of Agricultural, Livestock and Irrigation (MOALI), Myanmar; 2016/17. |

| [9] | World Bank. 2016. Myanmar - Analysis of farm production economics (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. https://0x9.me/JioIk. |

| [10] | K. T. New., M. Aung., T.T. Myint,, H. Hmwe,, and A. A. Myint, Hybrid Rice Research in Myanmar, Agricultural Research Journal, Department of Agricultural Research, Myanmar, 2004. |

| [11] | T, Win, Afforded Activities of Seed Production and Cultivation of Sin Shwe Lee Hybrid Rice for Food Security in Northern Shan State. East-Northern Command, Peace and Development Council, Lashio, Myanmar, 2005. |

| [12] | P.G. Zimbardo and M. R. Leippe, The psychology of attitude change and social influence. New York: McGraw-Hill. (1991). |

| [13] | M.P. Zanna and J. K. Rempel, Attitude A new look at an old concept. In D. Bartal & A. WKruglanski (Eds.), the social psychology of knowledge, 315-334 Cambridge University Press, 1988. |

| [14] | Bendar, A., and Levie, W.H. 1993. Attitude - change principle. |

| [15] | B. S. Robert and L. T. John, A Guide for Understanding Attitudes and Attitude Change, 1986. |

| [16] | Likert, R, “A Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes.” Archives of Psychology 22 (140): 55. 1932. |

| [17] | A, J, M. Hossain , C. B Casiwan., and. T. T. Ut, Hybrid Rice Technology for Food Security in the Tropics: Can the Chinese Miracle be Replicated in the Southeast Asia?, January 8-11, 2002 at Chiang Mai, Thailand 2002. |

| [18] | Yuan, L. P., Q. Y. Deng, and C. M. Liao. 2004. Current status of industrialization of hybrid rice technology. In Report on China’s development of biotech industries. Beijing, China: Chemical Industry Publishing House. |

| [19] | S.S. Virmani, C.X. Mao, R.S. Toledo, M. Hossain and A. Janaiah Hybrid Rice Seed Production Technology and Its Impact on Seed Industries and Rural Employment Opportunities in Asia, International Rice Research Institute, DAPO 7777, Metro Manila, Philippines, 2002-06-01. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML