Nagat Elmulthum1, Ilham Elsayed2

1Agribusiness, and Consumer Sciences Department, College of Agriculture and Food Sciences, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia

2Biomedical Department, College of Engineering, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Nagat Elmulthum, Agribusiness, and Consumer Sciences Department, College of Agriculture and Food Sciences, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Highlighting the importance of Saudi women contribution in growth and development, this paper aimed at investigating and analyzing the status and prospects of Saudi women in the job market under Saudi Vision 2030. Descriptive and quantitative analysis, using data from higher education statistics, and Saudi Arabian Monetary agency, was employed. Assuming exponential growth over time of male and female graduates from higher education institutions as well as unemployment rates, forecasts for the period 2017-2020 were estimated. Results indicates that, number of Saudi female students joining higher education institutions significantly increased during the period 1999-2013, however, the unemployment rate of males is far below that for females during the period 1999-2015. These, results are confirmed further, by significant gap with male domination in job market, indicating lower chances for Saudi females to join both private and public sectors, which confirms that, the job market does not react to the steady increase in the number of female graduates. Furthermore, results proved limited opportunities for Saudi labor (both males and females) to join job market in private sector, indicating that the private sector is not committed in regards to application of Sawada program. Forecasts results give signs of continued situation of increased number of female graduates, with significant gap favoring women, however, lower chances for Saudi women to join job market. Results indicated male domination of Staff members holding Ph.D. in Saudi Universities, however, realized equality in chances regarding M.Sc. holders gives signs of increasing Ph.D. staff members in the near future for both sexes. However, stated goals and obligations by Saudi Vision 2030 in relation to women is expected to have significant impact with prosperous prospects for Saudi women. Based on results the study recommends promotion of female staff members holding M.Sc. with expected spillover impact on qualifications of Saudi women. Further, the study recommends more restrictions assuring the application of Sawada program for nationalization of jobs with expected impact on Saudi nationals including women. Moreover, the study emphasized the coordination between higher education institutions and job market for well-trained higher education graduates in specialties demanded by the job market.

Keywords:

Saudi Vision 2030, Unemployment, Women Contribution, Job Market, Sawada

Cite this paper: Nagat Elmulthum, Ilham Elsayed, Prospects of Saudi Women’s Contribution to Job Market under Saudi Vision 2030: An Empirical Analysis 1999-2015, International Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 20-27. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20170701.03.

1. Introduction

Job market in Saudi Arabia adopted major changes by applying Sawada Program, Decision of the Ministry of labor (50) on 21/4/1415, to secure job opportunities to Saudis. However, rates of unemployment are increasing due to higher chances of employment devoted to non-Saudi workers especially in private sector, Elmulthum and Albisiry (2016), [1]. This could be explained, by the fact that higher education in Saudi Arabia provide limited opportunities to study diverse specializations required by the job market. This situation reflects the necessity of depending on non-Saudi workers in some fields, which constrain the application of Sawada Program. Based on descriptive and quantitative analysis Elsayed and Elmulthum, (2016), [2] investigated and analyzed the prospects of attaining Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Vision 2030, goal to empower Saudi women. Results indicated that, in contrast to higher number of female graduates lower rates of employment mark the job market for females. In addition, the contribution of women in selected sectors, namely, engineering, business directors and services is limited with male domination especially in engineering sector. Moreover, females have very limited opportunities in technical training. Furthermore, increased percentage of females joining higher education is a sign of prosperous opportunity to attain Saudi Vision 2030 goal of empowering Saudi Women. Investment in further education, increase in the number of graduates in specialties required by the job market with special emphasis on female graduates are recommended by researchers.Albahussein [2006], [3] examined the skills demanded by the private sector in Saudi Arabia. Emphasis was placed on the ability of higher education curriculum in providing these skills. According to his results, 78.8% of survey sample believe that the curriculum is not appropriate for provision of the required skills. Based on his results, the skills required by the job market include mastery of English Language and Information Technology, discipline, and ability to work in teams. Elmulthum and Adam (2010), [4] concluded that, upward trend of women education is not accompanied by higher employment opportunities for females. Furthermore, women have very rare opportunities to decide upon pivotal issues related to them and their society because of limited opportunities of assigning females in policymaking positions. According to Elsayed and Abdelmagid [2016], [5] argument, provision of higher opportunities to Saudi women to study diverse specialization, emphasizing engineering specialty, would open the door for Saudi women to join the job market. Based on Alebaidi (2009), [6] higher education institutions in the Arab region increased in number by 53.6% in 2008 compared to 2003. However, higher opportunities were available to students to join social and humanitarian specializations, where the percentage of students who join scientific and technical specializations does not exceed 31%. For Saudi Arabia, the number of Universities increased from 13 to 21, in addition to seven new private universities during the study period. Based on World Bank (2013), [7], non-Saudi low experienced labor dominates private sector job market. In addition, the contribution of female labor in Saudi job market increased, though at a lower rate compared to most of the Arab countries. According to Information and Studies Center at Eastern Chamber (2012) [8], the contribution of female labor in private sector in Saudi Arabia accounts for 8% of total job market in private sector. In addition, women family responsibilities affect their decision to join job market. Moreover, the main obstacle limiting the involvement of women in the job market is the low level of training resulting in a gap between job market requirements and graduate females experience.Increasing contribution of women in the labor force from 22% to 30%, reduction of unemployment rate from 11.6% to 7%, and increasing the contribution of small and medium institution from 20% to 35%s are announced goals of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia 2030 Vision, [9]. This could be attained by the obligations assured in 2030 Saudi vision including education to boost the economy, helping the small and medium institutions to get required funding, maximizing the investment ability, and supporting promising sectors (e.g industrial and mining industries). In addition, opening the doors of investment for the private sector to encourage innovations and competition is a declared commitment by Saudi 2030 vision aiming at increasing the contribution of the private sector in gross domestic product. The above obligation could lead to achieving Saudi Vision 2030 goals by bridging the gap between the output of higher education institution and the job market, (kingdom of Saudi Arabia Vision 2030, [9]). This research aimed at investigating and analyzing the present status of Saudi women employment and contribution to job market. Further, the research estimated some forecasts for education and unemployment emphasizing prospects of achieving Saudi 2030 vision goals in relation to Saudi women.

2. Methodology

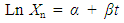

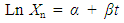

Secondary data on University graduates and the staff members at higher education institution were obtained from statistics of higher education in Saudi Arabia, [10]. In addition, data on unemployment rates and labor force were obtained from Saudi Arabian Monetary agency [11]. Descriptive and quantitative statistical analysis were employed. Assuming exponential growth over time for male and female graduates from higher education institutions in Saudi Arabia during the period (1999-2013), an estimation of the logarithmic linear form of equation (1) below given by equation (2) was obtained.  | (1) |

| (2) |

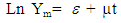

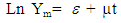

Where, X = number of graduatesα = constantβ = rate of growth of graduatest= time n = (1, 2) = male and females graduates from higher education institution respectively.Assuming exponential growth over time for male and female unemployment rate in Saudi Arabia, an estimation of the logarithmic linear form of equation (3) given by equation (4) was obtained, | (3) |

| (4) |

Where,Y = unemployment rateε = constantµ = rate of growth of unemployment ratet = time m = (1,2) = male and female unemployment rate

3. Results and Discussions

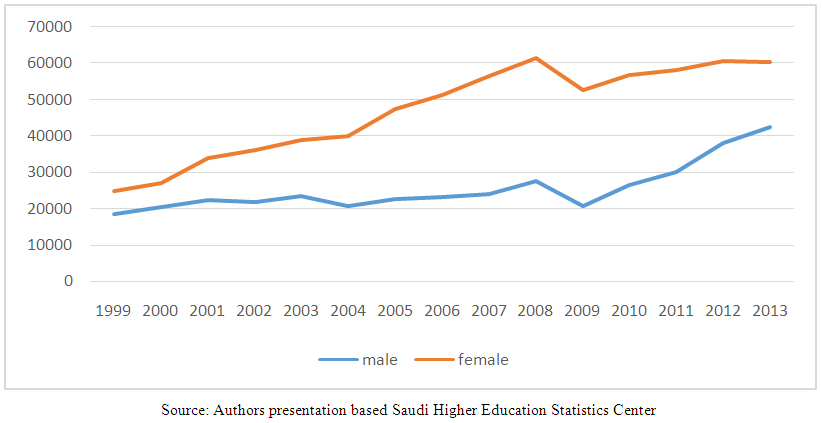

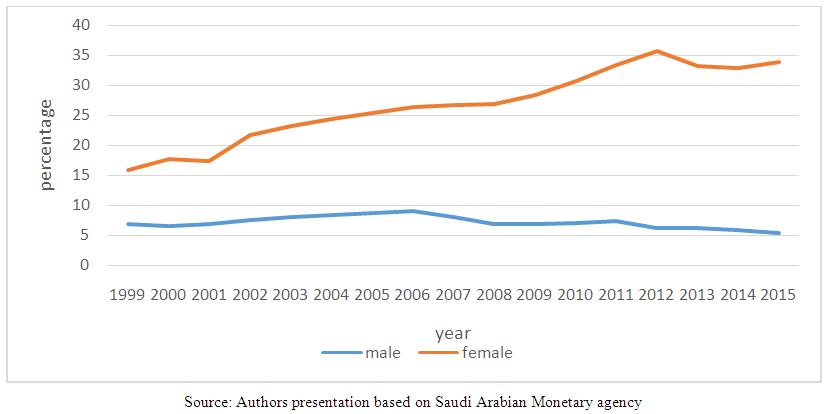

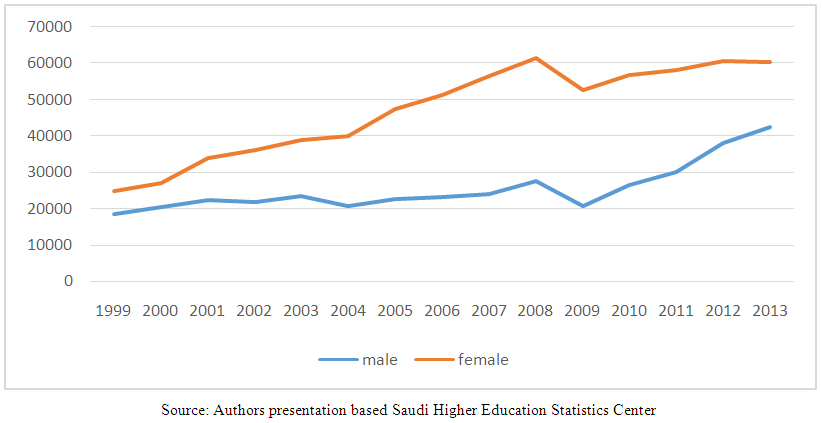

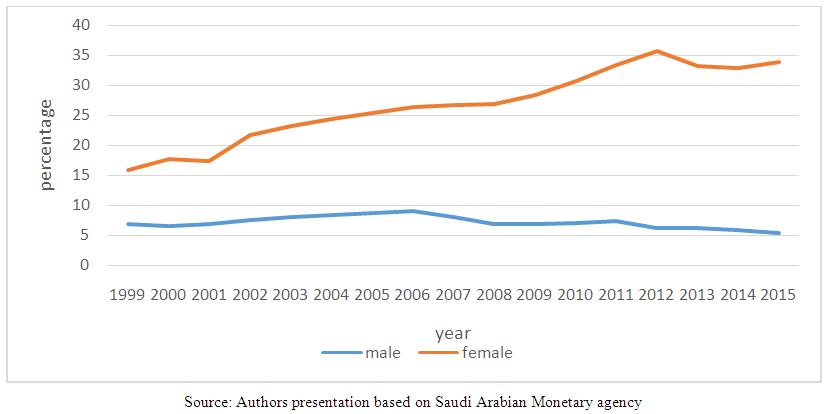

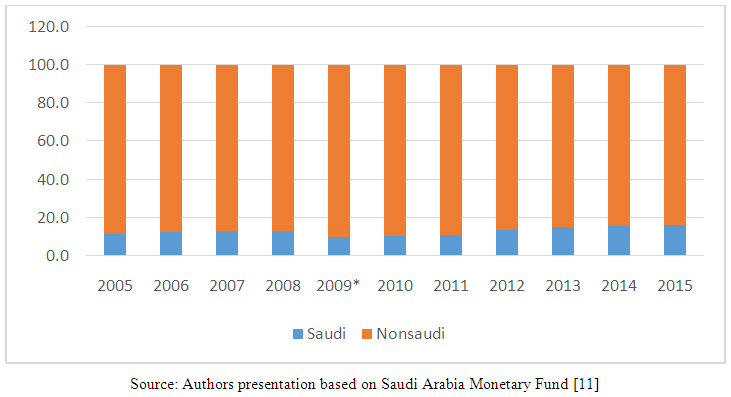

Figure (1) below shows that, number of female students joining higher education institutions in Saudi Arabia significantly increased during the period 1999-2013, subsequently the number of female graduates increased with respect to male graduates. Although the number of male graduates is increasing too, the gap is widening showing higher percentage of female graduates. On the other hand, Fig. 2 shows that, the unemployment rate of females during the period 1999-2015 is higher compared to males. Average unemployment rate in Saudi Arabia for females and males during this period is equal to 26.65 and 7.15 respectively. Figures 1 and 2 proved the sizable gap between male and female graduates in favor of women; however, the gap in unemployment supports male graduates. Both Figures predict the chances for achieving 2030 Saudi Vision goals to increased contribution of women in Saudi job market and reduced rates of unemployment. | Figure 1. Number of male and female graduates from Saudi Universities 1999-2013 |

| Figure 2. Unemployment rate for males and females in Saudi Arabia 1999-2015 |

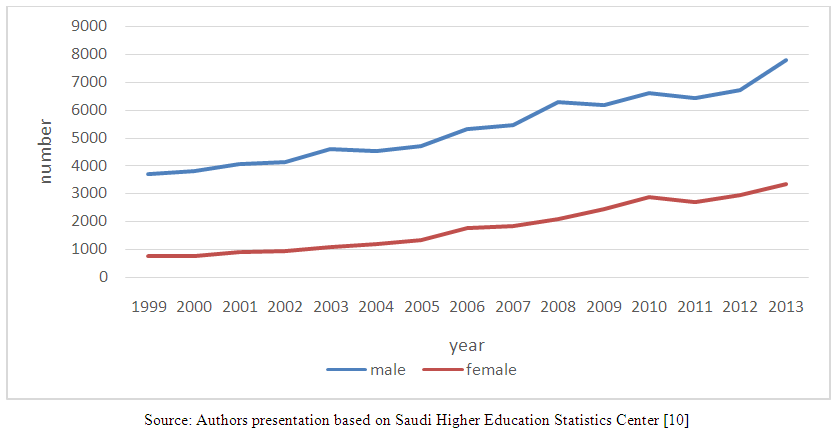

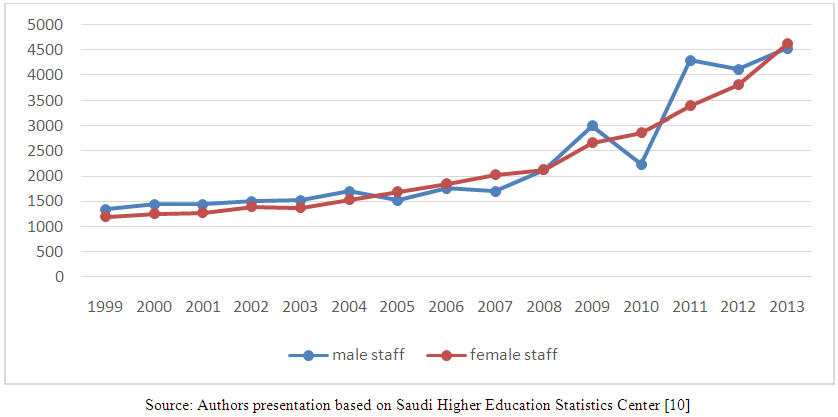

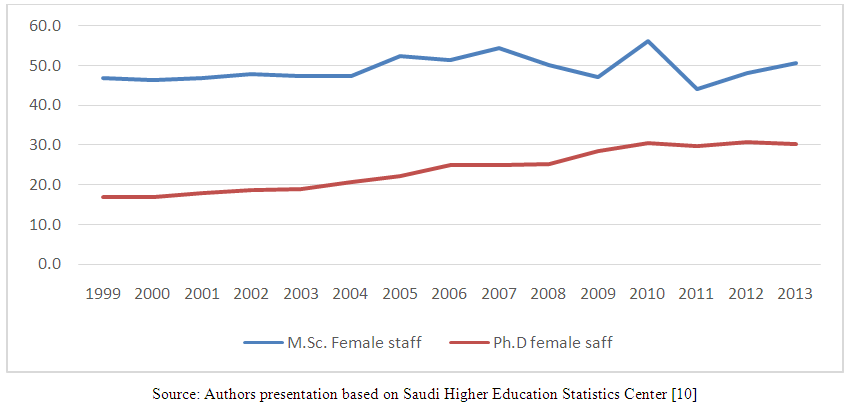

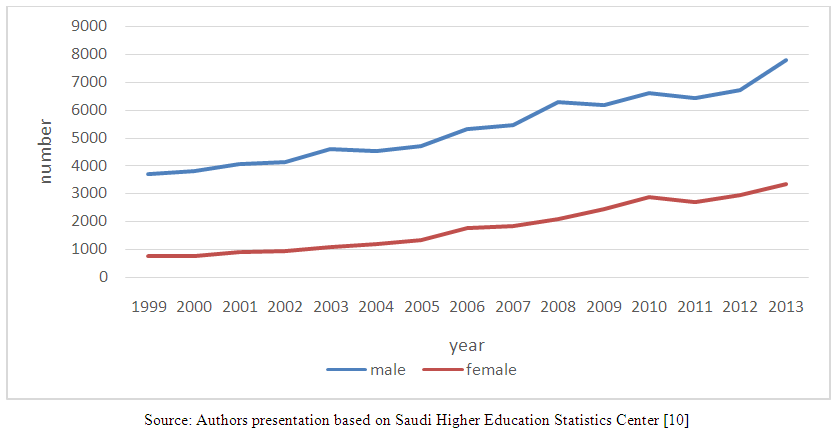

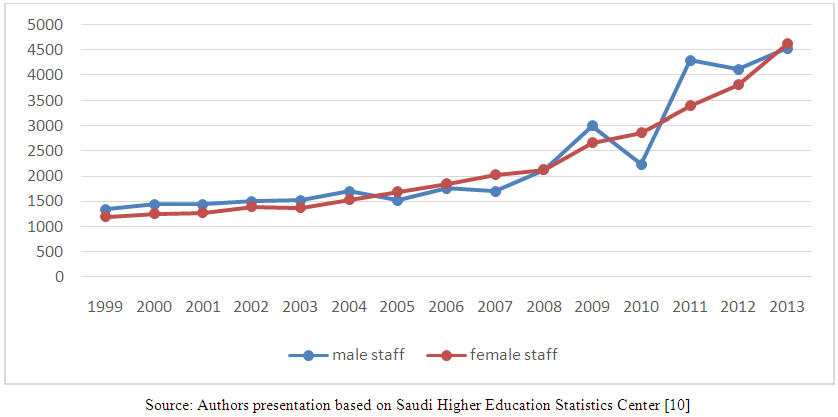

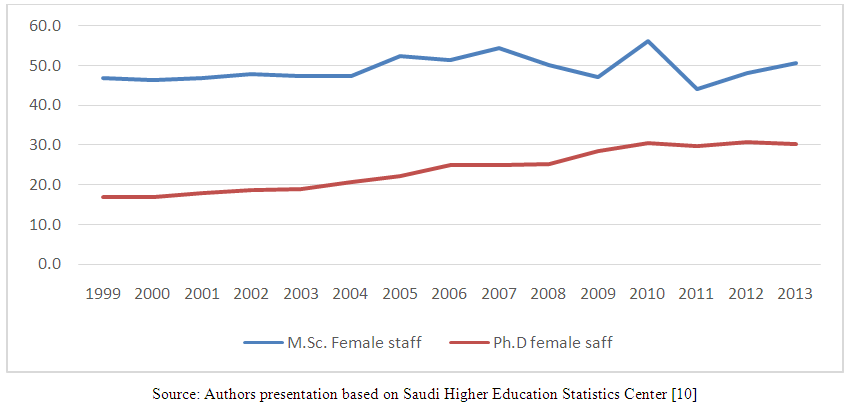

Competent female graduates have prosperous impact on Saudi Society, and hence, help in attaining Saudi vision goal to increased contribution of females in the job market. Figures (3) and (4) depict the number of Ph.D. and M.Sc. staff members in Saudi Universities, which indicated dominance of male staff for Ph.D. holders. However, both sexes receive similar chances for M.Sc. holders. This situation, gives signs of increasing Ph.D. female staff in the near future provided that opportunities are available for them to receive doctorate degrees. The expected promotion of female staff would support females and provide higher chances of female qualification given the fact that, the number of graduated females exceeds the number of male graduates as indicated by figure (1). Hence, prospects of attaining Saudi Vision goals of increased contribution of females in the job markets and lower unemployment rates are high. Referring to figure (4) equal contribution of staff members holding M.Sc. degrees from both sexes with female staff slightly exceeding male staff in some academic years. The above results are further confirmed by figure (5). Hence, national and international opportunities for female staff to obtain doctorate degree is expected to have a profound impact on female education in Saudi Arabia that would help in attaining Saudi vision2030 goals in relation to flourished economics. | Figure 3. Number of Ph.D Saudi staff members by sex 1999-2013 |

| Figure 4. Number of MS.C Saudi Staff members by sex 1999-2013 |

| Figure 5. Percentage of Ph.D and M.Sc. female staff members 1999-2013 |

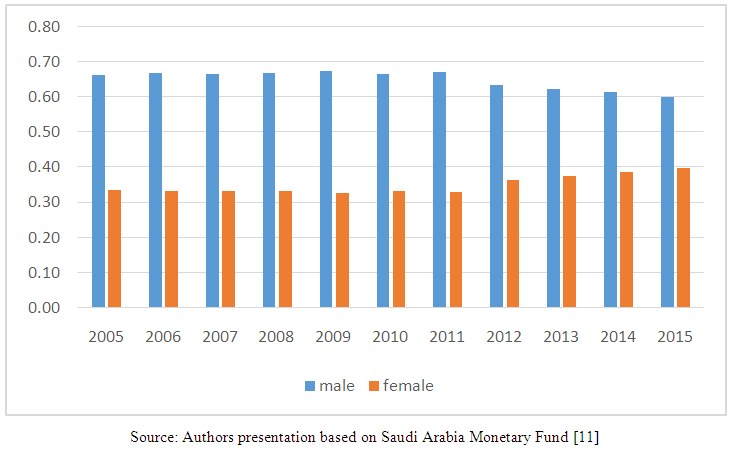

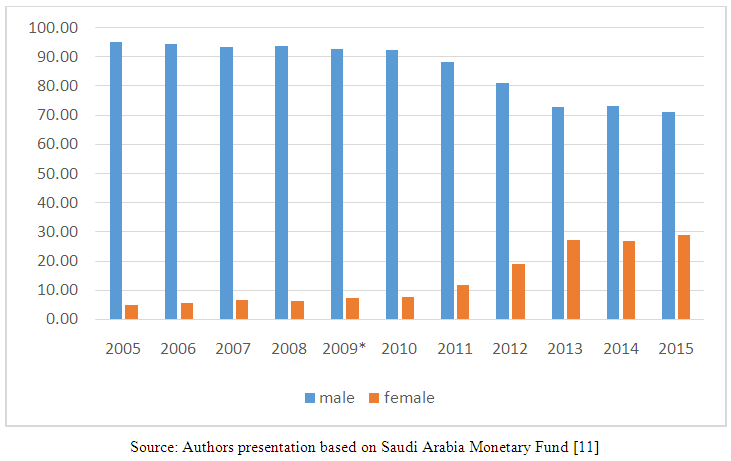

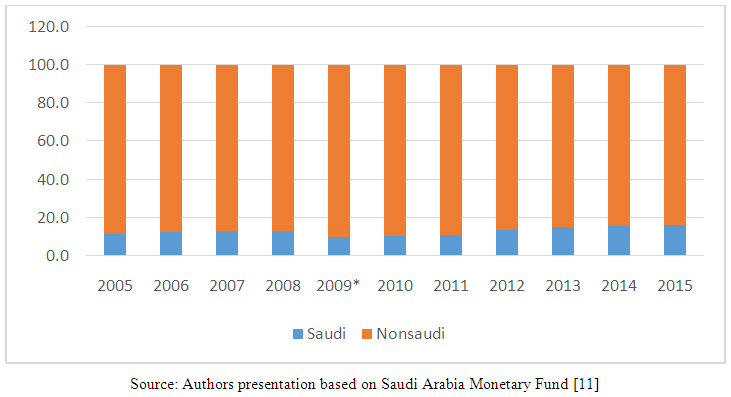

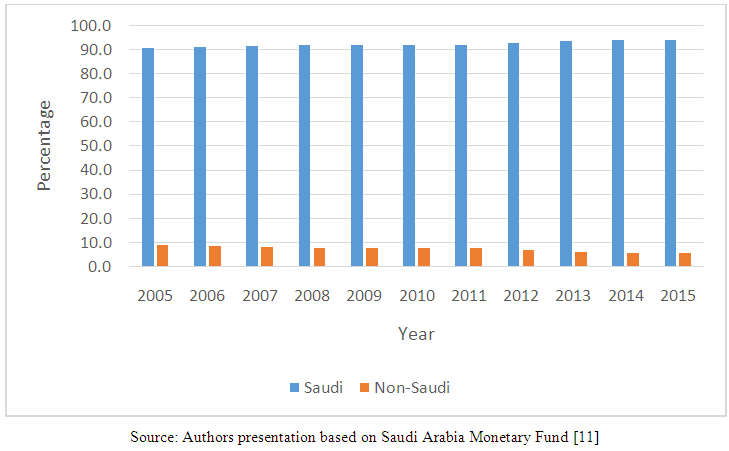

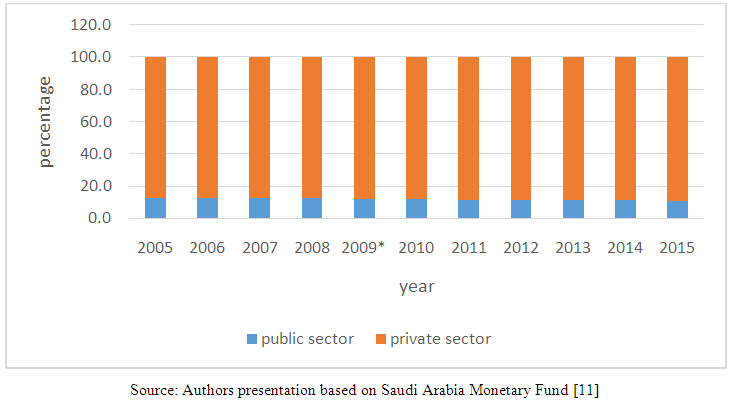

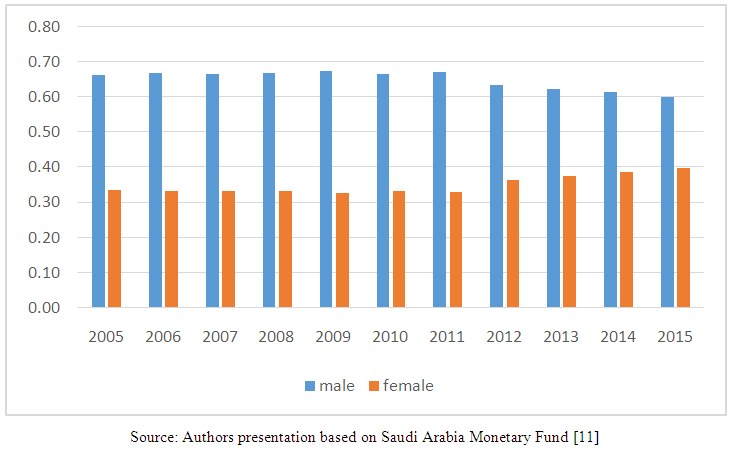

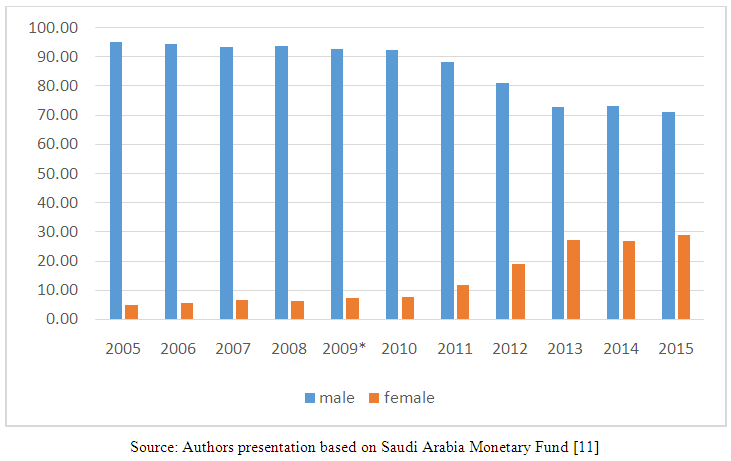

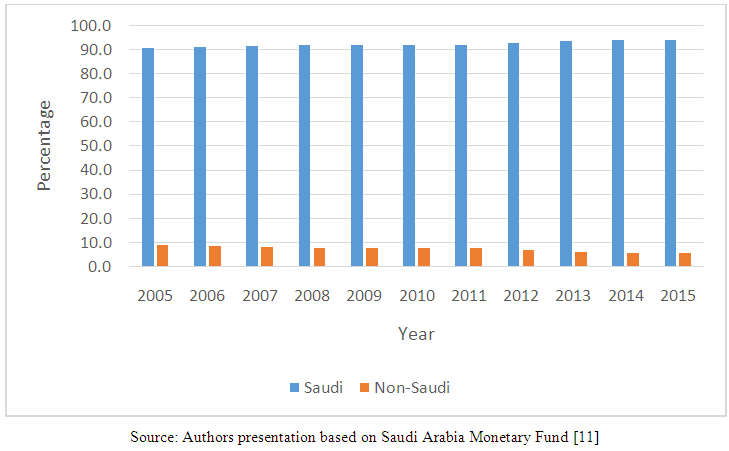

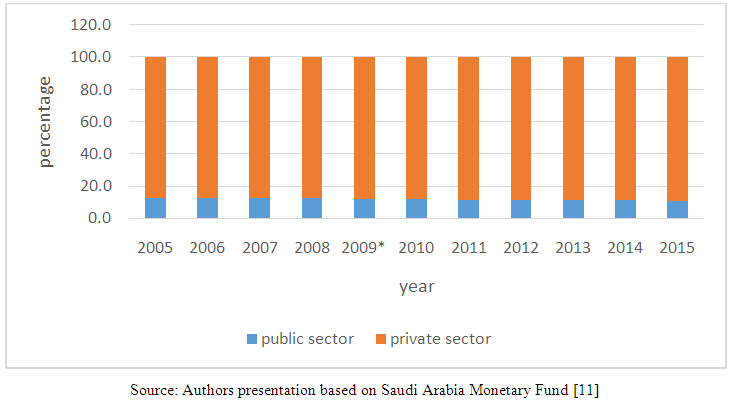

Figures (6) and (7) depict the percentage of Saudi labor force by sex in both public and private sectors during the period 2005-2015. The figures indicated that Saudi males dominates Saudi females in the job market in both sectors with significant gap in private sector. Hence, lower opportunities are available for Saudi females to join the job market especially in private sector. This result coincides with higher rates of unemployment for females shown in figure (2). Based on the results in figures (8) and (9), in contrast to public sector limited opportunities are available for Saudi labor as compared to non-Saudi to join the private sector. This result, indicated that the private sector is not committed to application of Sawada program decision (50) declared by the Ministry of labor on 21/4/1415 to guarantee job opportunities to Saudis. This situation is further aggravated by the fact that the percentage of labor in the public sector out of total labor employed in both sectors is far below labor in private sector, figure (10). Hence, domination of non-Saudi to the private sector where most of the labor force are working proved lower opportunities for Saudi with significant impact on females who have lower chances to join the job market with further negative impact on their rate of unemployment. This situation raise the importance of coordination between higher education institution and the job market for providing specializations required by the job market. Further, application of Sawada program in private and public sectors with special emphasis on private sector would have an impact on the rate of unemployment and increased contribution of women in the labor market. However, this necessitate qualified and well-trained male and female graduates.  | Figure 6. Percentage of Saudi labor force in the public sector by sex 2005-2015 |

| Figure 7. Percentage of Saudi labor force in the private sector by sex 2005-2015 |

| Figure 8. Percentage of Saudi and non-Saudi labor in the private sector 2005-2015 |

| Figure 9. Percentage of Saudi and non-Saudi labor force in the public sector 2005-2015 |

| Figure 10. Percentage of total labor in private and public sector in Saudi Arabia 2005-2015 |

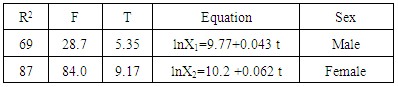

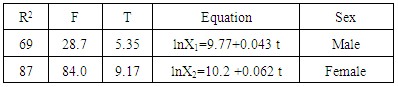

Estimated results using equations (2) and (4) mentioned previously are summarizes in Tables (1) and (2) below.Table 1. Estimated results using equation (2)

|

| |

|

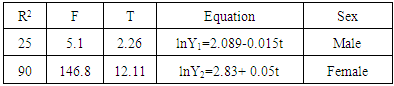

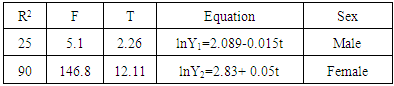

Table 2. Estimated results using equation (4)

|

| |

|

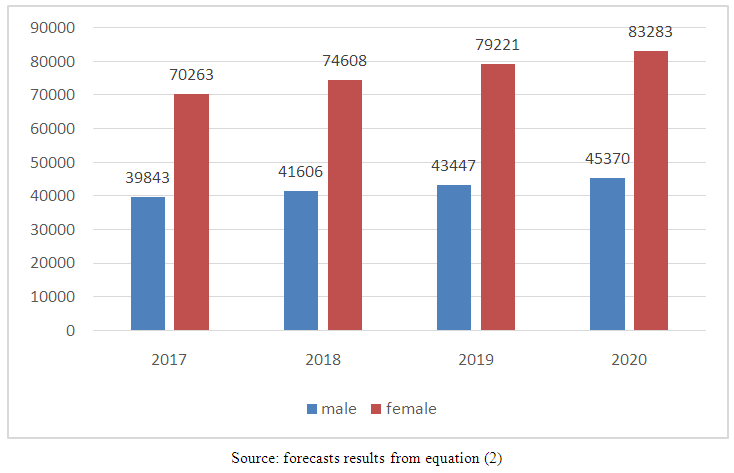

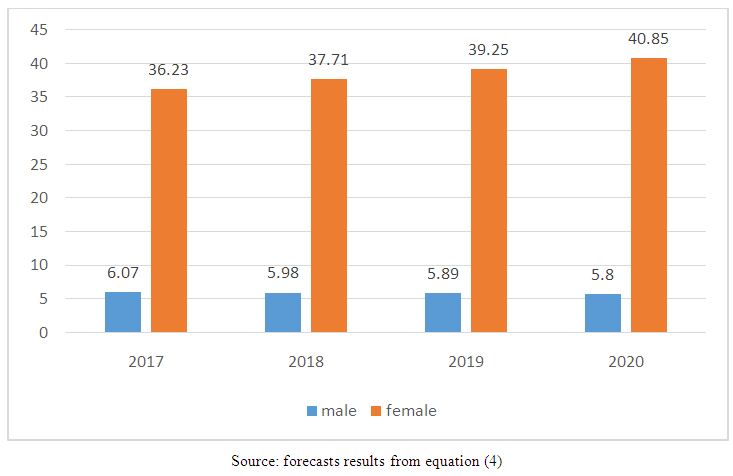

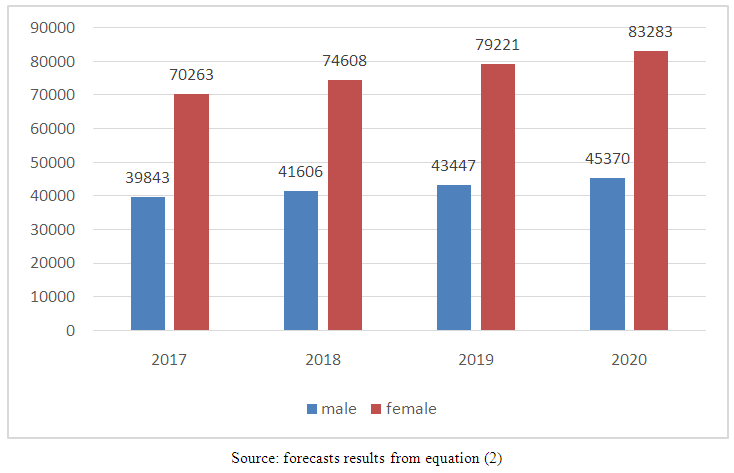

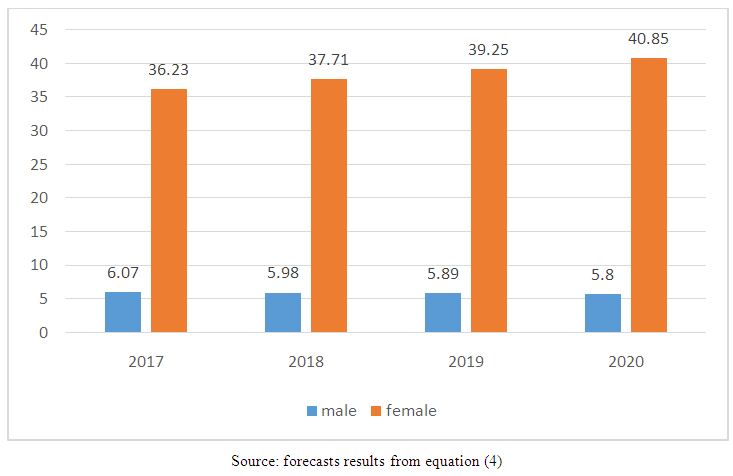

Where, R2 is percentage of variation in the number of graduates and the unemployment rate (male and female) due to time factor. T measures the significance of the time factor. F measure the overall significance of the model.Table (1) indicates that, time factor explained 69% and 87% variations in male and female graduates respectively. The rates of growth in male and female graduates measured by the coefficients of the time factor (coefficient in an exponential function measure the rate of growth) equal 4% and 6% for male and female graduates, respectively. This result indicated that the gap between graduates is maintained with female domination. Regarding the rate of growth in unemployment rate results in table (2) indicated that the time factor explained 90% of variation in the rate of unemployment for females, while only 25% of variation is explained by the time factor for males, which may be explained by fluctuation and variation in the rate of unemployment for males within a limited range. Coefficients of the time variable indicated that rate of growth in unemployment decreased at an annual rate of 1.5% for males and increased at an annual rate of 5% for females, which proves the lower opportunities for females to join the job market as compared to males. Equations (3) and (4) are significant at 1% level.Using the estimated equations for graduates from Saudi Universities and unemployment rates for both sexes, we estimated forecasts for graduates and unemployment rates during the period 2017-2020. Results depicted in figures (11) and (12) indicated that the gap in number of graduates will be maintained to the benefits of female graduates. In contrast, reduction of unemployment for males will continue at the disadvantage of female graduates, indicating the lower opportunities for females in the job market would continue. However, the implementation of Saudi Vision 2030 could have a substantial impact on female unemployment in Saudi Arabia since increasing the contribution of females in the job market and reducing the rate of unemployment are announced objectives of the Saudi 2030 vision. | Figure 11. Forecasts of number of male and female graduates from Saudi Universities 2017-2020 |

| Figure 12. Forecasts of male and female unemployment rates in Saudi Arabia 2017-2020 |

4. Conclusions

This study indicates that, the number of female graduates from higher education institutions in Saudi Arabia significantly increased during the period 1999-2013. However, job market in Saudi Arabia provide higher opportunities for male graduates to join both private and public sectors. Forecasts of number of graduates from Saudi Universities during the period 2017-2020 indicated higher rates of growth for females as compared to males. In contrast, forecasts of unemployment rates during the same period proved decreases in unemployment rate for males at the expense of females. Both private and public sectors favor employment of Saudi males as compared to females. Results indicated that the private sector is not committed to application of Sawada program resulting in domination by non-Saudi labor. The study proved that, employment opportunities for Saudi female staff holding Ph. D degree in higher education institution during the period 1999-2013 increased and the contribution of M.Sc. female staff members is significant with a negligible gap between males and females. Hence, prospects of attaining Saudi Vision 2030 goals of increased contribution of females in the job markets and lower unemployment rates are high. Confirmation of Sawada program, promotion of female staff members holding M.Sc., and coordination between the job market and higher education institutions for qualified graduates are recommendations by the study.

References

| [1] | Elmulthum N., Albisiry L., Higher Education Specializations and Labor Market in Saudi Arabia and University Graduates Challenges: Case Study Eastern Region"ـ, Jil Journal for human and social studies third year No. 26. Jil Center for scientific research, 2016; No. 26,133-149 (in Arabic). |

| [2] | Elsayed, I, and Elmulthum, N. “Potentials of achieving Saudi vision 2030 goal to empower Saudi women” international Journal of current research. 2016; 8, (12) 42716-42726. |

| [3] | Albahussein S., “Skills Required for Private Sector and Role of Higher Education Provision: An Empirical Study,” Economic and Administrative Sciences Journal. 2006; 22(1): 1-24. |

| [4] | Elmulthum N. and Adam N., “The Gap between Women Education and Empowerment: Case of Sudan”. Proceedings of 30th IFUW (ex- GWI), Mexico, 2010; www.ifuw.org/seminars/2010/index.shtml. |

| [5] | Elsayed I. S. M. and Abdelmagid I, “Suitability of Environmental Engineering Program for Female in Saudi Arabia: A Case Study on King Faisal University,” International Digital Organization for Scientific Information (IDOSI), Middle East Journal of Scientific Research, 2016; 24(11):3604-3610. |

| [6] | Alebaidi S. “Quality of Higher Education Assurance in the Context of Needs of Society,” 12th Conference of Ministers of Higher Education and Scientific Research in the Arab World, Harmonization of Output of Higher Education and Needs of Society in the Arab World 6-10 December 2009 Beirut. |

| [7] | World Bank, World Bank Selected issues, country report, 2013 No., 13/230. |

| [8] | Information and Studies Center at Eastern Chamber, “Towards Development of New Mechanisms to Eliminate Unemployment Among Women in Saudi Arabia,” Economic Affairs Sector, Alahsa, Saudi Arabia, 2012. |

| [9] | Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Vision 2030: http://vision2030.gov.sa/ browsed October 15, 2016. |

| [10] | Saudi Ministry of Higher Education: http://kr.moe.gov.sa/ar/eservices/Pages/ksa_gov_universites.aspx, browsed September 25, 2016. |

| [11] | Saudi Arabian Monetary Fund: http://www.sama.gov.sa/enus/pages/default.aspx. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML