-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Sociology

p-ISSN: 2169-9704 e-ISSN: 2169-9739

2015; 5(5): 175-179

doi:10.5923/j.ijas.20150505.01

Status of Cassava Farmers and Implication for Agricultural Extension and Rural Sociology in Gokana Local Government Area of Rivers State, Nigeria

Franklin Eziho Nlerum, Save Barkpue Kue

Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics/Extension, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Franklin Eziho Nlerum, Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics/Extension, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

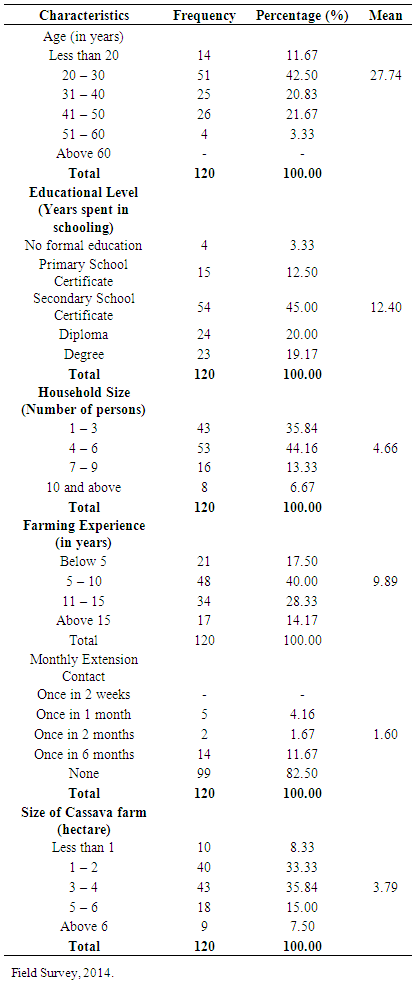

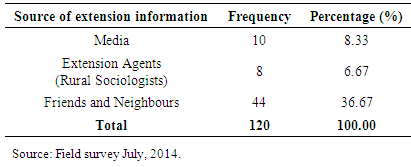

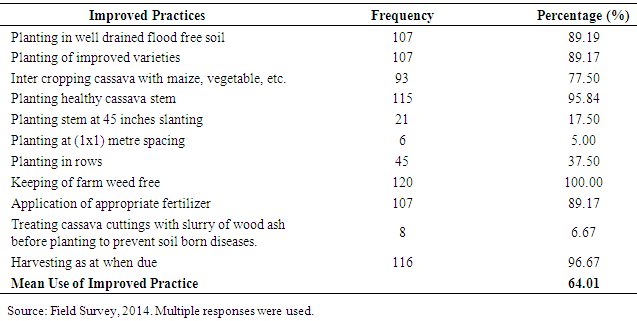

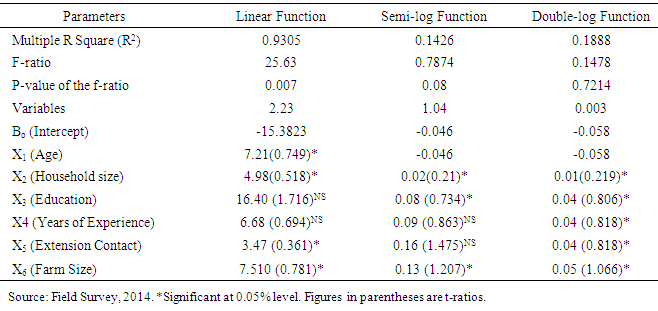

The study analyzed the status of cassava farmers and implication for agricultural extension and rural sociology in Gokana Local Government Area of Rivers State, Nigeria. Data were elicited from 120 cassava farmers with the aid of the questionnaire and interview schedule which were randomly distributed to respondents. Analyses of data were done with percentage, mean and multiple regression. Mean results showed that cassava farmers in the area, were 27.74 years old, spent 12.40 years in schooling, had a farming experience of 9.89 years and had a poor (1.68) monthly contacts with extension. Friends and neighbours, with 86.67% were the main sources of extension information on cassava production rather than extension agents which had 6.67%. Status of the use of improved cassava practice was 64.01% which is good enough. Results of the analysis of the relationship between farmers’ characteristics and use of improved cassava practice gave an R2 value of 0.9305. Age, household size, extension contact and farm size were significant determinants of the use of improved cassava practice in the area. Although the farmers were good in the use of improved cassava practice, their exposure to agricultural extension activities was poor. The study recommends urgent and better contacts between extension agents (rural sociologists) and farmers.

Keywords: Status, Cassava, Farmers, Implication, Agricultural extension, Rural sociology, Rivers State

Cite this paper: Franklin Eziho Nlerum, Save Barkpue Kue, Status of Cassava Farmers and Implication for Agricultural Extension and Rural Sociology in Gokana Local Government Area of Rivers State, Nigeria, International Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. 5 No. 5, 2015, pp. 175-179. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20150505.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Cassava originated from Brazil in South America and spread to West Africa by he early Portuguese explorers. Cassava is a latex-producing plant which grows up to the height of 1.8 – 3.6 meters depending on the variety. The two main kinds of cassava commonly grown in West Africa are the sweet cassava (Manihot palmata) and the bitter cassava (Manihot utilisima). The bitter cassava contains a bitter juice that must be extracted before it could be considered safe for human consumption. The sweet cassava on the other hand does not contain any harmful juice to human and animals and therefore can be eaten in any possible form. Agriculturally, cassava is propagated from cuttings. It is planted as a sole crop or intercropped with maize, yam, Vegetables, etc. Cassava is useful in the production of fufu, gari, flour, tapioca, animal feed, ethanol, starch, gum and glucose.The top four cassava producing countries in the world as at the end of 2010 according to Oppong-Apane (2013) were Nigeria with 37,504,100 tones, followed by Bazil with 24,524,300 tones, the third was Indonesia with 23,918,199 tones and the fourth was Thailand with 22,005,700 tones. The promulgation of the presidential initiative on cassava production in 2002 played important role in the sustenance of Nigerian position as the leading producer of cassava globally. The aim of the initiative was to produce more cassava for the purpose of producing ethanol, glue, glucose syrup and bread from cassava. Bakers under the initiative were to use 10 percent of cassava and 90 percent of wheat for bread production (Bamidele, et al 2008).Despite the fact that Nigeria is the largest producer of cassava in the world, the country is not an active participant in the international market on cassava when compared with Brazil, Indonesia and Thailand with lesser production output (Elemo, 2013). Leaders of world trade on cassava today are Thailand and Indonesia. Elemo (2013) added that 90 percent of the total cassava produced in Nigeria is eaten, while only as low as 10 percent is used for industrial products. President Goodluck Jonathan was emphatic in his desire to promote the export value of Nigerian produced cassava through the import substitution of wheat with cassava flour in the manufacture of bread. This is because in 2010 alone, Nigeria imported wheat worth N636 billion (naira). Elemo (2013) asserted that the substitution of wheat with 10 percent level of cassava in the baking of bread and confectioneries will lead to a high benefit of an annual savings of N63.60 billion (naira), creation of more jobs and reduction in the cost of bread. Irrespective of the fact that majority of farmers in Gokana area are cassava farmers, output of the crop is still struggling to attain its maximum potentials. The problem of the study was to know if cassava farmers in the area are actually exposed to agricultural extension and rural sociological activities. The research question therefore of the study was what is the current status of cassava farmers and their exposure to agricultural extension activities in the Gokana Local Government Area of Rivers State? In order to find answer to this research question, the objectives of the study determined the personal characteristics of the cassava farmers, analyzed the sources of extension information on cassava production and ascertained the status of the use of improved cassava practice. The null hypothesis of the study was that there is no significant relationship between personal characteristics of cassava farmers and the use of improved cassava practice.

2. Methodology

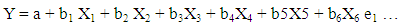

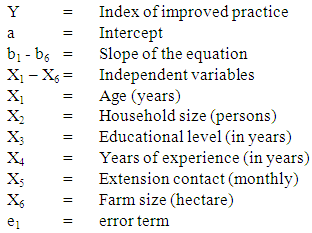

- This research work was conducted in Gokana Local Government Area (LGA) of Rivers State, South-South Nigeria. Its headquarters is at Kpor. Gokana Local Government Area has an area of 126 square kilometers and a population of 301,828 by the 2006 census. Gokana Local Government Area was created on 23rd September, 1991. It lies on the coastal low land of the Niger Delta in the south eastern part of Rivers State. Gokana is about fifty-four kilometers by road from Port Harcourt the capital of Rivers State and is located between Latitude 436 N and Longitude 72I E of the equator. It is bounded in the north by Tai Local Government Area and Khana Local Government Area, in the east by the Andoni Local Government Area, in the west by the Bolo people of Okrika Kingdom and in the South by the Ibani (Bonny) and the Atlantic Ocean. The major occupation of the people is agriculture. They produce cassava, yam, cocoyam, vegetables, livestock, fish and tree crops. The area is one of the major producers of cassava in Rivers State. Gokana people are also involved in such occupations as hunting, carving and weaving.The study population includes all the cassava farmers in Gokana Local Government Area of Rivers State. This population includes farmers who are involved in both the sole and intercropping systems of cassava production in the study area. The sample size of this study was 120 respondents. The sampling procedure adopted the simple random sampling method, in which every member in the population has got equal opportunity of being selected. Firstly, random sampling was used in selecting six communities out of a total of 17 communities in the area. The selected communities were Kpor, Bera, K Dera, Bodo, Yeghe and Deken. Random sampling method was also adopted in selecting 20 cassava farmers from each of the selected communities to have the sample size of 120 respondents. List of farmers used were obtained from the Area Office of the Rivers State Agricultural Development Programme.The data for the study were collected from primary sources through the administration of the questionnaire for literate respondents and interview schedule the non-literate respondents. An enumerator who was trained for this purpose was used in the distribution and retrieval of data collection instruments. Mean, percentage and multiple regression analysis were used for data analyses. The model of the multiple regression analysis used is explicitly presented in agreement with that used by Amamgbo et al (2006) as:

| (1) |

3. Results and Discussion

- Table 1 show that the mean age of the respondents was 27.74% years, with 20 – 30 years age range accounting for the highest with 42.50%. This finding implies that cassava farmers in the area are made up of youths and people who can be referred as being in their active and productive years.

|

|

|

|

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The study has shown that the current status of cassava farmers in the study area has a good future for cassava production because more farmers are in their active and productive ages, have a good farming experience and are cultivating sizeable hectares of cassava farms. Although, there was an appreciable use of improved cassava production practice by the farmers, their exposure to agricultural extension and rural sociological activities was poor. Poor extension contact of the farmers with a higher sourcing of production information from friends and neighbours, rather than the extension agents (the rural sociologists) were identified as problems. The study recommends better contacts between extension agents and cassava farmers and higher activities of agricultural extension and rural sociological workers to assist farmers access firsthand and direct production information from informed experts in the area.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML