-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Sociology

p-ISSN: 2169-9704 e-ISSN: 2169-9739

2015; 5(1): 16-30

doi:10.5923/j.ijas.20150501.03

Academic Background, Socio-Economic Status and Gender: Implications for Youth Restiveness and Educational Development in Rivers State

Oboada Alafonye Uriah1, Nwachukwu Prince Ololube1, Daniel Elemchukwu Egbezor2

1Faculty of Education, Ignatius Ajuru University of Education, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria

2Faculty of Education, University of Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Nwachukwu Prince Ololube, Faculty of Education, Ignatius Ajuru University of Education, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The study presented in this article is a follow up to a study that was previously completed by the authors (Uriah, Egbezor & Ololube, 2014) on the challenges of youth restiveness and educational development in Rivers State. The aim of the present study is to test the relationship between academic background, socio-economic status and gender and their implications for youth restiveness and educational development in Rivers State. The data for this study were collected through questionnaires, and were analyzed using quantitative methods to strengthen the validity of the findings. The sample size of this study comprised 700 respondents (124 Females and 576 males) who were randomly selected for the study from the Social Development Institute (SDI) Okehi. Thus, the sample consists of 652 Ex-militants out of the 1, 050 registered in the camp and 48 officials of the SDI camp. The data analysis involved the use of multiple statistical procedures, which includes Percentages, Mean Point Value, Cross Tabulation, and One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). The results obtained from the data analysis show that the basic roles of youth restiveness has implication on educational development, which tend to be similar across the world. Further analysis of both literature and empirical results showed significant relationship between academic background, socio-economic status, gender and youth restiveness, which in turn affects educational development. This paper is addressed to the Nigerian government, stakeholders, and researchers who know little of the theme of this study. We look forward that this study may present solution to the problem of youth restiveness and its impact on educational development in Rivers State.

Keywords: Youth restiveness, Academic background, Socio-Economic background, Parents, Gender, Education, Development

Cite this paper: Oboada Alafonye Uriah, Nwachukwu Prince Ololube, Daniel Elemchukwu Egbezor, Academic Background, Socio-Economic Status and Gender: Implications for Youth Restiveness and Educational Development in Rivers State, International Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 16-30. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20150501.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction/Background

- At the entrance of the 21st century, Niger Delta region and its surrounding regions saw an unprecedented surge in youth restiveness. Nigeria is usually faced with the challenges of bringing up their young ones. This task of bringing up the young, making members of the society in terms of culture, and imbibing positive attitudes and behaviours normally begins at home and continues in the school. This situation is normally described as socialization (Ololube, 2011, 2012). When the processes of socialization break down, the result is not always favourable for social order. Many times, the effort of homes are thwarted by other factors that tend to hold back internalization of treasured family values. Issues like academic background, socio-economic background and gender tend to influence youths to deviate from the acceptable norms and values. The gap between people in modern times has been bridged by development in information and communication technologies (ICT), consequently, traditional societies become impacted by value changes from more advanced countries. And various forms of social challenges impact most modern nations these days. Most of these apprehensions are as a result of economic depression, which manifest as unemployment leading to deviant behaviours among the youths. These anti-social behaviours usually become what is termed youth restiveness (Uriah, Egbezor & Ololube, 2014). In recent times, youth restiveness in Nigeria is a prominent issue and there has been an increase in the occurrence of acts of violence and lawlessness, including things like hostage taking of prominent citizens and expatriate oil workers, as well as oil bunkering, arms insurgence, cultism, etc., especially in the Niger Delta region. Nevertheless, globally youth restiveness is not a recent phenomenon. Various forms of youth restiveness that are economically, politically, or religiously motivated have existed for a long time (Anasi, 2010).Youth in this context can be seen as young men and women who are no longer children, but not yet adults. Others have gone ahead to give a definitive age bracket to youths as those within the age range of 15-30 years. In fact, in some cultures in Nigeria it may not be out of place to see people (especially men) of even 40-45 years of age claiming youth membership. Hence, the concept of youth is a relative one: a person is a youth if he or she believes so. On the other hand, youth restiveness refers to a plethora of activities expressed in the form of hostage taking of foreign nationals, local oil workers and citizens for ransom; oil pipe-line blow ups; illegal bunkering; peaceful or violent demonstration; bombing of public places, etc, in the Niger Delta of Nigeria (Epelle, 2010).The term youth depicts a specific stage in the development of human beings. There are legal, physiological and chronological dimensions to the definition of the youth. As a result, there is no standard definition for the term youth. Despite the lack of consensus among scholars, Nwanna-Nzewunwa, Girigiri and Okoh (2007) defined a youth as any person that is over twelve (12) years but not more than forty (40). Akinboye (1987) defined youth as any youngster between twenty and thirty years. The World Health Organization (WHO) viewed youth as anybody between the ages of 15 and 24. The Federal Republic of Nigeria (FRN) (2004) officially placed the age bracket of youths between 16–30 years. What this means is that youth can be found in the primary and secondary schools as well as tertiary institutions. Yet there are others who are out of school with all its grave implications to the individual and the society (Okorosaye-Orubite, 2008).What makes the youth so important is that they are described as a big reservoir of labour and the most vibrant age bracket in human population or the marrow of the human resource of any country (Girigiri, 2007). Whether as students or not, youths are always at the forefront in the struggle against injustice, oppression, and exploitation. When the expectations of the youths are thwarted, delayed or denied, they have the tendency to be restive. Restiveness could be seen in someone who have excess expendable energy, zeal and drive to forge ahead. By their nature, youths are full of so much vitality, which make them restive. These energies when consciously and positively channeled received social acceptance in creative vendors like music and dancing, enrolment in the forces, gainful employment, engagement in economic activities, academic and community development activities, participation in competitive sports among others. On the other hand, if these energies are not adequately and appropriately handled, the result is negative restiveness leading to anti-social activities such as hostage taking, kidnapping, cultism, rape, stealing, prostitution, demonstration, wanton destruction of lives and properties, rioting, etc. Negative restiveness is as a result of the prevailing conditions such as oppression, high handedness, unemployment, corruption, injustice, etc. Agina-Obu (2008) refers to restiveness’ as a kind of human behaviour geared towards the realization of individuals or groups’ needs. It emanates from individuals or group failures or inability to meet their needs through institutional provisions or arrangements that results in youth restiveness. Hence, the youths opt to take laws into their own hands.Using the Lockean Social Contract theory as a framework for analysis, Epelle (2010) posited that oil violence in the Delta region is largely a manifestation of the processes of state failure and collapse. It is indicative of the people’s insurgency against the Nigerian state, which has not been able to faithfully deliver on its terms of the social contract to the Niger Delta people. According to Epelle (2010), for oil violence to be properly tackled, there must be a complete reorganization and refocusing of the Nigerian state. Furthermore, there must be justice, adequate funding of development projects, the political will to punish criminals accordingly, checking arms running in the region and creation of employment opportunities for the youths (Ojakorotu & Gilbert, 2010).Youth restiveness in the development of the Niger Delta region cannot be overemphasized because restive activities seem to be related to the nature of development accrued to the region. In essence, there seem to be a relationship between youth restiveness and the development levels of the area (Uriah et al., 2014). For instance, Adesope, Agumagu, & Chiefson (2000) observed that the spate of youth disturbances is particularly serious in the Niger Delta region. According to them the nature of exploitation of the region at the expense of the indigenes has been a major source of worry to the area and has resulted in restive activities. Youths have been at the forefront of agitation for compensation for the exploitation of the Niger Delta area. This is not very surprising given the fact that they form a great portion of the entire society (Uriah et al., 2014). According to Okorosaye-Orubite (2008), persons between the ages of 6-30 years form about 59 percent of the population of Nigeria, while the productive active segment (15-30 years) constitute 47 percent of the productive population of the country. And they are the “brain and brown” of the societies to which they belong.Substantiating Adesope et al. (2000), Seiders (1996) opined that rural youth make up a large segment of the total rural population; however, they are often neglected and overlooked by government policy makers and international agency development strategists. This can be attributed in large part to the overwhelming concern for immediate solutions to problems of national development with an accompanying inaccurate perception that youth are not yet productive and contributing members of society. Swanson and Claar (1984) explained that millions of young people living in rural areas are a significant and untapped resource available to assist in rural development process. Adesope (1999) reported that the youths because of their sizeable portion in the entire population are useful engines for development. The need to harness and therefore tap their numerous physical and mental resources becomes necessary. However, Obuh (2005) gave reasons such as low level of exposure, poor leadership, and lack of cooperation among youths, lack of encouragement from elders, as problems affecting their involvement in community development. Despite this, the youths have been found to have moderately high participation levels in community development and also favourable attitude towards community development (Adesope, 1999). In addition, Adesope et al. (2003) observed that youths are involved in community development because they want to help their communities, to be recognized, to interact with peers, and to gain personal benefits. This is a manifestation of their meaningful contribution to the development process (Adesope et al., 2010).Therefore, one could ask, what is the purpose of education? In answering this question, one must critically evaluate the diverse functions of education with reference to recent changes in educational policies around the world. Principally, education functions as a means of socialization and social control. It helps to encourage the young to develop into “good citizens” and prepares people for employment and for productive contributions to society (Ololube, 2012). It can be a way of reducing social inequality or a way of reproducing social inequalities. When executed with excellence, it benefits the individual, society and the economy (Ololube, Agbor & Uriah, 2013). Education, in its broadest sense, is any act or experience that has a formative effect on the mind, character, or physical ability of an individual (for example, an infant is educated by its environment through interaction with its environment) (Briggs, Ololube, Kpolovie, Amaele & Amanchukwu 2012). It is the entire range of experiences in life through which an individual learns something new. In a technical sense, education is the process by which society deliberately transmits its accumulated knowledge, values, and skills from one generation to the next through institutions and instruction (Ololube, 2011). Given the centrality of education across the globe, education is a powerful instrument of social progress without which no individual can attain development (Lawal, 2003).It is in realization of the above roles of education and realizing same that a lot of youths have left the school due to restiveness and militancy that the Rivers State government decided to establish the Social Development Institute (SDI) in Okehi, Etche Local Government Area of Rivers State with the aims of identifying the needs of the restive youths in other to rehabilitate them.In view of the enormity of the challenges posed by youth restiveness and its grave implications to the corporate existence of Nigeria and the lives of the citizens, the purpose of the study is to make a theoretical and empirical investigation of the causes of youth restiveness and its implication on educational development in Rivers State. In specific terms, the study will ascertain the following:• Explore whether the academic background of the restive youths influence their agitations;• Investigate whether the socio-economic status of the youths influence their agitations; and • Ascertain whether gender has a role to play in the agitations and aspirations of the restive youths.

1.1. Research Questions

- Based on the purposes of the study, the following research questions guides this study:• To what extent does academic background of the restive youths influence their agitations?• To what extent does socio-economic background of parents influence youths agitations?• To what extent does gender influence the agitations of restive youths?

1.2. Hypotheses

- The following null hypotheses testable at 0.05 level of significant were formulated to guide the study:• There is no significant relationship between academic background of the restive youths and their agitations.• There is no significant relationship between the socio-economic background of parents of the restive youths and their agitations.• There is no significant relationship between gender and the agitations of the restive youths.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Education and Youths Restiveness

- The relevance of education in the aspiration of individuals cannot be over emphasized. Education because it involves not one but several complex processes is difficult to define. Elobuike in Ololube (2009), summits that education means many things to many people and different things to different people. To pupils, students (whether in secondary schools, polytechnics, universities, monotechnics etc), education could be a means of acquiring the qualifications for job, a way of escaping lowly social class origins or a way of realizing their life aspirations. Education whether in the form of formal, informal or non-formal modes is very important and has direct bearing with career development and individuals. Education in its formal form is a determining factor in the realization of career aspirations. It is as a result of the foregoing that Agabi and Okosaye-Orubite (2008) stated that education is power, it is a process of acquiring knowledge and ideas that shape and condition man’s attitudes, action and achievements. It is a process of developing the child’s moral, physical, emotional and intellectual powers for his contribution in social reform. It is the process of mastering the laws of nature and utilizing them effectively for the welfare of the individual and for social reconstruction. It is the art of the utilization of knowledge for complete human survival.Education is an in-born power and potentialities of individuals in the society and the acquisition of skills, aptitudes and competencies necessary for self realization and coping with life problems (Achuonye & Ajoku, 2003). It is the process of acculturation through which the individual is helped to attain the development of his potentials and their maximum activation when necessary according to right reasons and to achieve thereby his perfect self-fulfillment. Education helps to harness or tap the potentials of individuals and it is an essential tool for refining the talent, skills or potentials of individuals. In the context of present contemporary society, education is what helps individuals to specialize in the profession that they are best suited for. The school is a significant agent of socialization where individuals acquire various aptitudes, knowledge and skills, which eventually influence their career aspiration. Research findings (e.g., Ololube, 2012, 2011) have indicated a relationship between the type of school attended by individuals, the nature of curricula offerings to which individuals have been exposed and their career pursuits.Zakaria (2006) observed that education does not influence the career aspiration of restive youths. He noted that restive youths who even had first degree or diploma indicated to be trained in career other than the area they were certificated. In the same vein, Uriah et al. (2014) explained that most of the restive youths were school drop outs who were sent off from school for poor academic performance, few others had certificates that can readily qualified them for employment in competitive environment. In this instance, the restive youths required retraining in newly found areas that can qualify them for employment. Igbo and Ikpa (2013) explained that the more these restive youths are educated and trained, the more they will be relevant and contribute meaningfully to the development of their environment. They futyjer stated that modern societies with their modern institutions and industrial order can only be achieved and sustained by a population transformed from their traditional values, beliefs and behavior to a modern set of values and behaviour by modern education. However, Uriah et al. (2014) opined that if the right education is given to the restive youths, they will contribute enormously to the economic, political and social development of their communities.

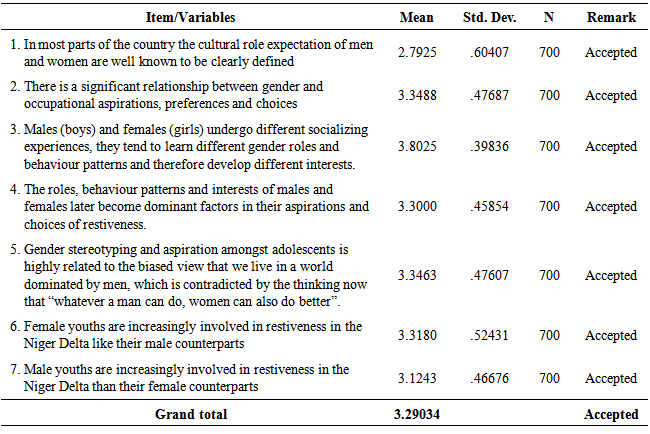

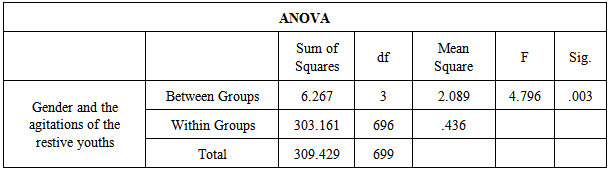

2.2. Gender and Youth’s Restiveness

- In most parts of the country the cultural role expectation of men and women are well known to be clearly defined. Some studies (Otto, 1998; Kinanee 1994; Onyije, 1991) have shown significant relationships between gender and occupational aspirations, preferences and choices. Since males (boys) and females (girls) undergo different socializing experiences, they tend to learn different gender roles and behavior patterns and therefore develop different interests. These roles and interests later become dominant factors in career aspirations and choices. Okonkwo, (1980) in his study on some determinants of vocational preferences or aspirations among Nigeria secondary school students, found gender differences to be a dominant factor. Male adolescents preferred engineering, medicine and agriculture while female adolescents preferred nursing and teaching. Gensinde’s (1996) own study also indicated that gender played an important role in determining the career aspirations of adolescents. Other research findings which have supported gender differences in the aspirations of adolescents include the works of Yuh (1990), who, in her study of some correlates of vocational orientations of some Nigerian adolescents, discovered that significantly, more male adolescents preferred realistic, investigative and enterprising careers than female adolescents. Sosanya (1996) indicated that male adolescents or youth were significantly more interested in outdoor, mechanical and persuasive occupation than female adolescents or youths, who were more interested in computational, artistic, literary and clerical activities. Osuagwu (1992) showed that males adolescents significantly preferred more mechanical activities while female adolescents were significantly more interested in persuasive, artistic, literary, musical, social services and clerical activities. These past studies have indicated a degree of difference that remained fairly constant from the early 1900s up until about 1990.Nwachukwu (2004) explained that 1990’s were a watershed period in occupational desegregation, as indicated by significant declines in measures of occupational differences. The high wall of gender stereotyping came tumbling down. Oladele (2002) noted that gender stereotyping in occupational aspiration of adolescents was highly related to the bias view that we live in a world dominated by men, which is contradicted by the thinking now that “whatever a man can do, women can also do better”. Woothen (1997) noted that advances of women’s movement, the enactment of laws prohibiting gender discrimination, increase in female enrollment in higher education and professional schools, the steady increase in women’s labour force participation and reductions in gender stereotyping in both education and employment all contributed to the new trend in adolescents’ career aspirations. Female adolescents continued to make in-roads into male dominated occupations. Occupations that were considered “ab initio” as the exclusive preserves for men have witnessed the presence of a significant number of female folks. For example, female youths also get involved in restive activities like protest, cultism, illegal bunkering and robbery etc. (Idumange, 2009).Davidson (2006) observed that data available for broad occupational groups for the past two decades clearly indicated two major points. First, the gender distribution of many occupations have shifted substantially. Second, despite these shifts, women and men still tend to be concentrated in different occupations. In the same vein, Charles and Grusky (2002) explained that although in the last half-century, women have streamed into labour force and assumed well-paid professional and managerial positions. There remained much entrenched gender inequality as a great many occupations are still hyper-segregated. They attributed this occupational segregation to gender essentialism, a deeply rooted cultural assumption that women are well-suited to service and nurturance and that men are well-suited to physical labour, technical task and abstract calculation or analysis. Another factor that aided occupational segregation is the cultural premise of male primacy, which demonstrates by the thinking that men are more competent and status-worthy than women.Job aspirations of restive youths although affected by the dynamics in the society as shown in the literature examined above, showed that most female youths had enrolled in occupational areas earlier classified as male dominated occupations. Elegbede (2006) observed that more female adolescents are enrolled as operators, fabricators and constructors. Ibegwura (2007) observed that there is no established pattern of job preferences by restive youths in Erema. He noted that educated adolescents insisted on job placement based on fairness and equal opportunities. However, the fact that there were more male graduates indicated that the females had less representation especially in asking for managerial positions in oil-related firms in the area. Charles and Grusky (2002) explained that as a society, we have long subscribed to a liberal egalitarian “contract” in which emphasis was placed on ensuring that individual preferences, however, they may be formed can be pursued or expressed in a fair (i.e. gender-neutral) contest. Under this, overt inequalities of opportunities are questioned, but nothing prevents individuals from understanding that their own competencies and those of others in terms of standard essentialist visions of masculinity and feminists are there. It is important to note that as liberal egalitarianism spreads, women increasingly enter into higher education and paid labour market and yet they do so in ways that reflect their own “female preferences”, the social and interpersonal sanctions associated with gender-inappropriate work and the essentialist prejudices of employers. There are indeed many signs that a revised form of egalitarianism is developing. Most notably, conventional sociological understandings of the role of socialization, social exchange and power differentials in generating preferences have diffused widely in contemporary industrial societies, implying that preferences and choices formerly regarded as sacrosanct are increasingly treated as outcomes of unequal and unfair social processes. This deeper form of egalitarianism has motivated some parents to attempt to minimize gender bias in the socialization of children at least in the early years of childbearing before the unremitting influence of society wide essentialism typically undermines their efforts. Padavic and Reskin (2002) observed that although gender stereotyping in occupational aspirations and preferences is still very strong, however, competencies, interests and acquisition of skills are very significant indices of judging entry into various professions or occupations. Hull and Nelson (2000) and Newman (2006) enunciated that arguments on gender influences on occupational aspirations will continue unabated in sociology and allied fields. The authors are of the view that while such influences exist, recent findings indicate that there is greater female entry into traditionally male lines of work. But such entry does not necessarily mean that there is gender equality as men have not noticeably increased their representation in female dominated occupations. Female youths also engaged in anti-social activities prevalent in the society today like the men such as: prostitution, violent protest, cult membership and clashes, vandalization of oil pipe-lines, drug abuse, armed robbery and arms insurgence, etc. (Idumange, 2009).

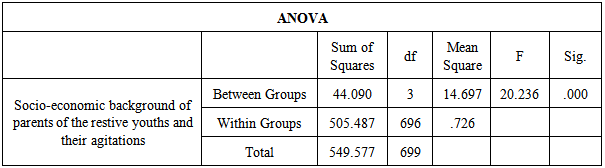

2.3. Socio-economic Background and Youths Restiveness

- Socio-economic background of restive youths is an important consideration especially as it influences the actions and activities of restive youths. Newman (2006) quoting Weber (1970) explained socio economic status as the prestige, honour, respect and power associated with different class positions in the society. It is the position of individuals that measures such factors as education, income, type of occupation, place of residence in a given population, ethnicity and religion. The National Centre for Educational Statistics (2008) defined socio-economic status as an economic and sociological combined total measures of a person’s work, experience and of the family’s economic and social positions in relation to others based on income, education and occupation. The analysis of Parents’ socio-economic status, the household income, education and occupation are integrated as well as the attributes of the individuals in the family. Davis and Smith (2004) enunciated that socio-economic status is obviously influenced by wealth and income, but it can also be derived from achieved characteristics such as educational attainment and occupational prestige, and from ascribed characteristics such as race, ethnicity, gender and family pedigree.By dichotomization, socio-economic status of parents could be broken into three categories: high, middle and low socio-economic status. By implication, families with high socio-economic status would often have more successes in preparing their young children to be successful and attain greater heights in life. They may have the knowledge and information to help prepare their children for the best positions in life, unlike the middle and lower classes with limited opportunities (Ololube, 2012).Agulana and Nwachukwu (2002) posited that youths or adolescents differ from one another in social class or socio-economic status. Socio-economic status they defined as a relative studying in society based on an individual income, power, occupation, education and prestige. They explained that it would not be wrong to say that the children of bankers, medical doctors, teachers, merchants, etc. have different upbringing from that experienced by children of peasant farmers, domestic workers, cleaners, laborers, petty traders, and so on. They went further to state that differences exist between high, middle and lower class families in the kinds of activities they engage in.Chauhan (1996) noted that in studying the socio-economic status of any giving individual, sociologists have therefore often relied on socio-economic indices such as occupation, level of education and income. Based on one of these indicators, the various social classes are usually organized into an overall hierarchical structure. The commonest and basic structure is usually the higher or upper, middle and lower class structures.Chauhan (1996), in his study of Indian adolescents found out that a child’s particular socio-economic inheritance may have a direct and important effect on the career open or attractive to him than does his physical inheritance. The economic and occupational level of the home affects the vocational goals of youths by influencing their aspirations to be similar to those held by their parents and by discouraging aspiration to level much above or below the parents’ occupational status.A child’s biological endowments in terms of personality traits are transmitted to him in form of genetic inheritance. If both parents possess high intellectual capabilities and transmit the traits for intelligence to the child, that child is very likely to be highly intelligent and benefit from education, which will likely enhance his opportunity for better occupations. On the other hand, a child of very low intellectual parent who inherited this trait may turn out to be an imbecile who may later find it difficult to be properly educated and gainfully employed. To a large extent, the parents determine the initial environment into which a child is born and provide for his needs. Thus, if the parents can afford a congenial environment for the development of the hereditary potentials of the child such as providing for Medicare, proper feeding, toys,, exercising and educational facilities, the child may benefit immensely and develop well. Such a child will also be properly exposed to various occupations available to the society.Parental socio-economic status and intelligence have either facilitatory or inhibitory effect on the child, depending on the traits inherited from the environment in which he is brought up. The self and work roles begin early in life and the home in conjunction with its related social system has great influence on them. The family comprising the parents, siblings, relatives, friends and neighbors, providing the initial social encounter through socialization process also provides the modes with which the child can identify. Usually a child may consciously or unconsciously learn from the parents by role-playing or invitation.Parental or family set-standards may greatly affect the occupational choice of the adolescents or youths and so motivate them to be achievement oriented. Thus, families where some particular careers are of great priority, tend to orientate their youths towards achieving that goal. The motivational force is as high as the children tend to yield willingly, work very hard and fall into those chosen careers. Often they provide all necessary materials for playing occupational roles. Family influences including child rearing practices and socio-economic level, appear to affect career choice and development among youths.Denga (1990), Stated that the economic situation or occupational level of one generation seems to remain like that of the previous generation. In any case, there has been instances of many parents who are classified as low socio-economic status families who have either acquired better education and occupy key posts in the society or their children have achieved the feat. Such parents are often seen as strong motivating forces behind their children urging them to strive hard.Nwachukwu (2003) stated that boys from high income earning families tended to assume that they would go for higher education and have occupational choice restricted to a professional executive type. And also found out that boys from lower income families tended to prefer skilled jobs which offer higher rates of study. It is common today to see youths born into either higher or low socio- economic status families tending to take a career choice in terms of how real they are to them, what prestige is attached to such career and what satisfaction they can get from their career.Egberike (2005) explained that in Nigeria today, with the wide exposure and establishment of educational institutions even in rural areas, parents either of low or high socio-economic status now urge their children to work hard at their studies in order to occupy one of the highly prestigious jobs or positions. Tams (2006) observed that the socio-economic background of restive youths influenced their occupational aspirations. The youths from high and middle socio-economic background take to career that tend to be lucrative, prestigious or jobs that they can easily make or earn a lot of money. It is necessary to explain that youths from high and middle socio-economic background are usually the arrowheads of most of the protest and demonstrations. While this does not portray that they organize or champion such protest or demonstrations, the fact remains that they have the connection, contacts, the economic muscle and privileged position to make the people at the corridors of power to easily hear or listen to their perceived grievances. In the Niger Delta region which is highly militarized, the funding for some of the guns and ammunition used in confronting state security machinery because of the high cost and huge financial outlay is supplied by youths from high and middle socio-economic families (Ololube et al., 2012).Thompson (2009) posited that socio-economic background of the restive youths do not play any significant role toward their job aspirations. He explained that in Nigeria in general and Niger Delta Region in particular, where individuals suffer untold hardship and deprivation, most career aspirations are accidental in nature and driven by the survival instinct. In such cases, the need for survival is what propels individuals and motivate them in whatever they are doing. This seems to be the order of the day especially in oil bearing communities where individuals desire to work with multinational oil companies not necessarily because of their socio-economic background, but the desire to make money and make ends meet. Amakedi (2006) in a similar vein noted that individuals go into politics because of the access to state powers and the easy money which come their ways.In the midst of poverty, uncertainty and deprivation, individuals especially the youths may do whatever jobs that come their way instead of insisting on a particular job. As a result of high number of unemployed youths, it is common to see youths doing jobs that are not related to their educational pursuit. Thompson (2009) enunciated that what determines or influences the career aspirations of most restive youth is the influence and authority which they command (physical strength), raw talent and economic considerations rather than socio-economic background or status. He explained that a combination of these factors could catapult a youth from a low socio-economic background to a position of power and affluence. As a result of very weak institutions in the country, and the divide and rule policy of multinational companies, youths who are seen as capable of organizing violent activities and protest against the activities of such companies or criticize lapses in governance are often pacified or settled” with jobs that may not necessarily relate to their academic pursuit.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

- This descriptive survey employed quantitative research methods, because much of what we know about people’s knowledge and attitudes is based on responses to survey questions (Creswell, 2007; Creswell & Plano, 2007). Since we cannot directly observe people thinking, this is one way to begin to understand the process by which people acquire interpretations of survey items (or beliefs about a particular topic). Researchers may find that they gravitate towards qualitative research because such methods provide a descriptive glimpse into which issues are of importance and offer more solutions to pressing national concern (Uriah et al., 2014).Survey research is likely to remain valuable because it is an efficient way of collecting information from representative samples, and these offer greater generalizability of the larger population than the non-representative sample, while maintaining the privacy of respondents. Thus, simple random and purposive sampling procedures were employed in data gathering. This is a situation whereby every person living in the Social Development Institute (SDI) of Rivers State had a purposive opportunity to be selected. The research design of this study sets up the framework for―adequate tests of the relationships among variables. The design tells us, in a sense, what observations to make, how to make them, and how to analyze the quantitative representations of the data. The design further tells us what type of statistical analysis to use (Richardson, 2006; Ololube, 2009, Ololube et al., 2012).

3.2. Population of Study

- The population for this study consists of 1,050 restive youths undergoing rehabilitation at the Social Development Institute (SDI), Okehi in Etche Local Government Area of Rivers State. Out of the 1,050 Restive youths, 900 are males while 150 of them are females from various Local Government Areas of the State. These Youths have demonstrated the likeness to take lives and destroy properties in other to protest the various forms of injustice manifesting in both private and public sector of the economy as well as the inadequacy of the social amenities and lack of employment opportunities in the state.

3.3. Sample and Sampling Techniques

- The purposive sampling method was employed in selecting the female and male restive youths for the study. 124 female were used in the study. On the other hands, 576 male were randomly selected for the study from the Social Development Institute (SDI) Okehi. Thus, the sample consists of 652 Ex-militants out of the 1, 050 registered in the camp and 48 officials of the SDI camp. On the whole, 700 respondents’ were used for the study.

3.4. Instrument for Data Collection

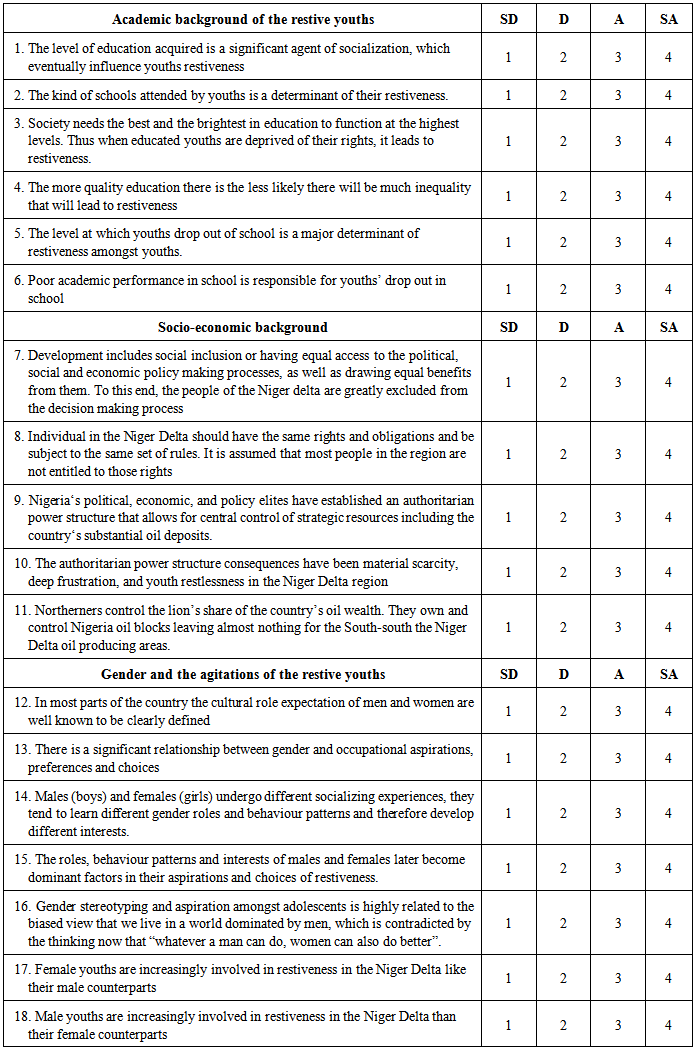

- Data collection for this study was done through a questionnaire designed by the researchers titled “Youth Restiveness and Educational Development Questionnaire (YREDQ)”. This questionnaire consists of two sections. Section “A” contains information on the demographics of the restive youths, while section “B” of the instrument contains substantive issues on academic background, socio-economic background and gender. The instrument was designed along the Likert format of strongly Agree (SA), Agree (A), Disagree (D) and Strongly Disagree (SD). The responses were scored as follows: Strongly Agree (SA) = 4, Agree (A) = 3, Disagree (D) = 2, and Strongly disagree (SD) = 1 respectively.

3.5. Validation of the Instrument

- A research is related to the possession of the quality of strength, worth, or value (Keeves, 1997, p. 279). A valid research finding is one in which there is similarity between the reality that exists in the world and the description of that reality (Ololube, 2006, p. 110). In this research endeavour, the researchers used the term validity in a fairly straightforward, commonsense way to refer to the correctness or credibility of the description, explanation, interpretation, conclusion, or other sort of account that is presented in the instrument. The instruments used in this research were valid because the researcher has taken time to comply with the formalities and procedures adopted in framing a research questionnaire (Nworgu, 1991, pp. 93-94). To validate the instrument, the questionnaire was given to research experts in the design of questionnaire who read through and made necessary corrections. The second process that was used to validate the research instrument was that the questionnaire was pre-tested and the responses from the respondents were used to improve on the items. In summary, the validity of the instruments used in this study rests on an overall evaluative judgment founded on empirical evidence and theoretical rationales of the adequacy, appropriateness of inferences and action based on the test scores (Xiaorong, 2001, p. 54; Ololube, 2006, p 111).

3.6. Reliability of the Instrument

- The reliability of the variables in the questionnaire might be termed to be reliable judging by the fact that it varies between 0 and 1 and the nearer the result is to 1-, and preferably at or over 0.8- the more internally reliable is the scale (Bryman & Cramer, 2011; Ololube, 2006). The cumulative reliability of .812 shows a strong reliability of the 18 items in the research instrument. See the table below for detail.

|

|

3.7. Administration of the Instrument

- The questionnaire was administered simultaneously one after another to the restive youths at the SDI camp through the instructors and resource persons in the camp. Before the administration of the instrument, the instructors were briefed on the objectives of the study. The filled instruments were retrieved immediately and prepared for scoring and analysis.

3.8. Method of Data Analysis

- The questionnaires were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 21: Mean, Cross tabulation, ANOVA was the means of analysis. Mean was used to determine the strength of some variables to the weakness of others. Cross tabulation was used because it is one of the simplest and most common ways of demonstrating the presence or absence of a relationship (Bryman & Cramer, 2011). ANOVA analysis, set at p. < 0.05 significance level, was used to determine the relationship between variables and the respondents’ bio data on the impact of youth restiveness and its implication on the educational development in Rivers State of Nigeria. The mean scores determine the acceptance or rejection of the rating items in the section. In order to make decisions from results obtained, the mean responses were computed thus: 4+3+2+1= 10/4 = 2.5. In the light of the above computation, any mean score more than 2.5 was accepted, while the mean score of 2.5 and below was taken as rejected.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analyses of Respondents Personal Data

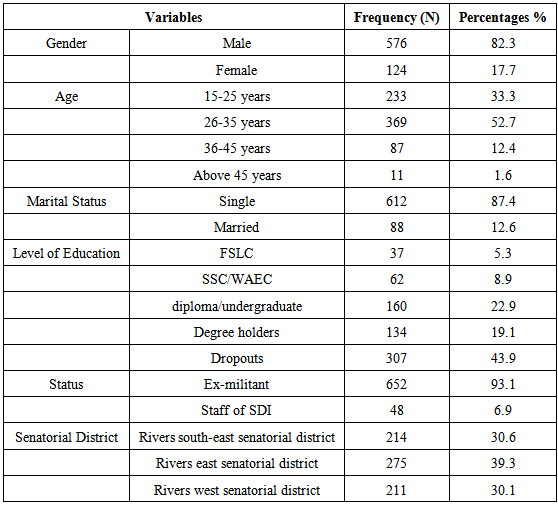

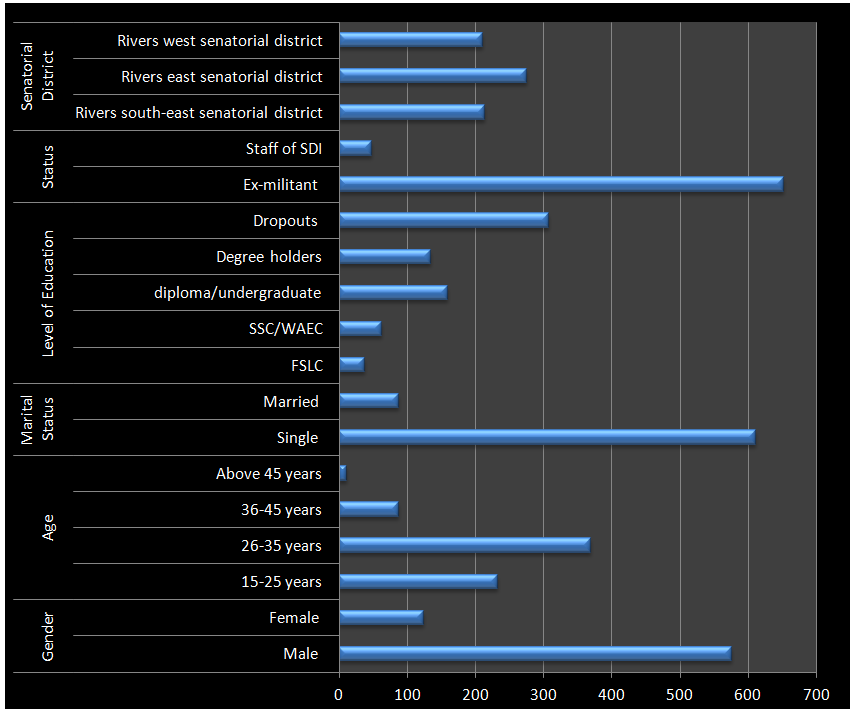

- In this study (see table 3 and figure 1), the first set of data analyses that was conducted was a descriptive statistics (frequency [N], percentage, mean and standard deviation). Data from section ‘A’ of the questionnaire yielded information about respondents’ personal data.The data analysis for respondents personal information showed that 576(82.3%) were male, while 124(17.7%) were female.Based on the age of the respondents, the majority of them 369(52.7%) were between 26-35 years, while 233(33.3%) were aged 15-25 years and 87(12.4%) were 36-45 years, whereas 11(1.6%) were above 45 years.With regards to respondents marital status, 612(87.4%) were single, while 88(12.6%) were married.Data on respondents’ level of education revealed that 37(5.3%) hold First School Leaving Certificate, while 62(8.9%) hold Senior Secondary School Certificate, and 160(22.9%) hold Diploma Certificate and some of them are undergraduates, whereas, 134(19.1%) are degree holders and the majority of the respondents 307(43.9%) are dropouts from various institutions in the state.The data further revealed that 652(93.1%) were ex-militants, while 48(6.9%) were staff of Social Development Institute (SDI).The data for respondents’ senatorial district revealed that the majority of the respondents 275(39.3%) were from Rivers East Senatorial District, while 214(30.6%) were from Rivers South-east Senatorial District, whereas 211(30.1%) were from Rivers West Senatorial District. See table 4 for detail.

|

| Figure 1. Bar Chart Representing Respondents Demographic Information |

|

|

|

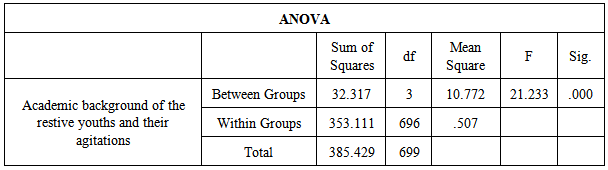

4.2. Results of Hypotheses

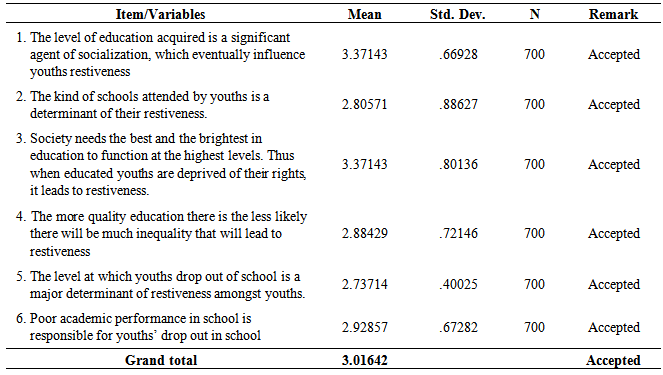

- Hypothesis 1: There is no significant relationship between academic background of the restive youths and their agitations.The result from the ANOVA analysis (table 7) conducted revealed that there is a significant relationship between academic background of the restive youths and their agitations. Respondents are of the view that the level of education acquired is a significant agent of socialization, which eventually influences youth restiveness; the kind of schools attended is a determinant for their restiveness and poor academic performance in school is responsible for youths’ drop out in school. This is depicted in the F-ratio = 21.233; p. > .000, tested at .05 level of significance. Therefore, hypothesis one was rejected.

|

|

|

5. Conclusions

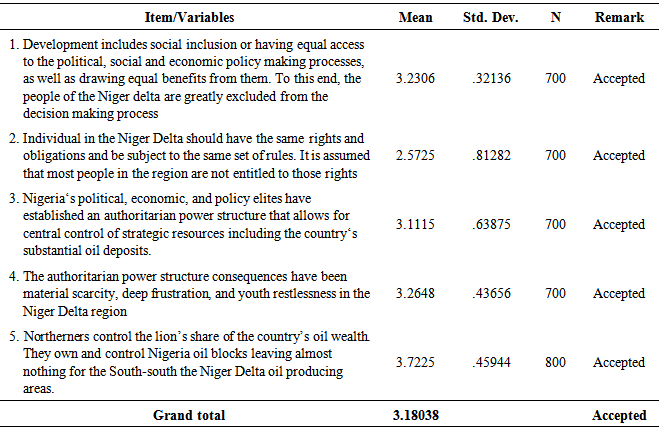

- This study investigated the role of academic background, socio-economic status and gender on youth restiveness and its implication on educational development of the Niger Delta region. This research provides insight, for example, into how people think and perceive agenda into their everyday and long term concerns, and into the contexts in which their ideas and attitudes have developed over a period of time (Barton, 2006; Ololube et al., 2013). Consequently, this study has shown us that education and development in the Niger Delta region is largely affected by youth restiveness. It was learned through this study that there is a significant relationship between academic background of the restive youths and their agitations (see, UNDP 2006). This study has proven that the researched hypotheses were rejected as the evidence from this study shows that there is a significant relationship between the socio-economic status of parents of the restive youths and their agitations in the Niger Delta region.The question remains, why do the causes of youth restiveness have such a strong hold on educational development in the Niger Delta? As the literature reviewed in this study suggests, the component parts of youth restiveness—academic background, socio-economic and gender feed into the desire and ability of a people to pursue both basic and more advanced education (Uriah et al., 2014; Ololube, 2013; Ololube et al., 2013). The connections between youth restiveness and educational development inform us that it is not simply enough to offer amnesty to ex-militants. In order to ensure that the youths have the opportunity to succeed, live in a secure society, participate in governance, Nigeria must first remove the obstacles that prevent them from experiencing decent and dignified standard of living. Obstacles like education underdevelopment, gender issues, poverty, hunger, disease, insecurity, and socio-economic and political inequalities have to be addressed. The importance of removing these obstacles is heightened when we realize that the youths are key to national development, therefore, should not be marginalized and oppressed (Uriah et al., 2014; Okaba, 2005; Aghalino, 2012).Fostering educational development (and eliminating educational underdevelopment) in Rivers State is not an easy task, particularly, considering the continuous increase in youth restiveness, which is as a result of their withdrawal from school systems, and their absence from any form of formal education. Nonetheless, there are a number of steps that can be taken in the direction of fostering educational development. Nigerians must work with their government to instill both a sense and system of accountability for state and corporate bodies to ensure that those companies presently in the region, as well as those likely to enter the region in the future, can be held accountable for their actions, including the effects of oil exploration and drilling on the physical environment of the region (Aigbokhan, 2000; Uriah et al., 2014). It is also important that Nigerians adopt and advance the language of peace, mutual respect and development, which is a universal remedy for educational advancement of the state and the nation at large. The more the language and terminology of youth restiveness becomes an accepted norm the less likely it is that states and federal government in Nigeria will be able to get away with violations of cultural values. Finally, it is imperative to continue to stress to all levels of government, the connections between youth restiveness and education and the connections between education and national development. If governments can come to appreciate that the underdevelopment of Rivers State leads to the underdevelopment of the nation and that the underdevelopment of the nation cannot be remedied in an insecure environment. Thus, government should begin to work towards the eradication of educational inequalities among citizens, issues of gender disparity, and socio-economic inequalities (Annan, 2000a, b; Ololube et al., 2012). In realization of the findings of this study, it is obvious that for Rivers State to flourish and grow educationally, and for our democracy to sustain liberty and justice, the next generation of Nigerian citizens must acquire the knowledge, skills, abilities and commitments needed to grow the economy of the state. In this paradigm, knowledge and socio-economic equality are regarded as the key to the sustainable development of economies as well as the individuals who live in the nation. Thus, this research has identified academic background, socio-economic status and gender issues as the causes of youth restiveness, which in turn are major factors that has impeded educational development in Rivers State.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML