-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Sociology

p-ISSN: 2169-9704 e-ISSN: 2169-9739

2014; 4(5): 120-125

doi:10.5923/j.ijas.20140405.02

Transformation of Cultural Values of Momosad in Agriculture Land Management in the Buffer Zone of the Bolaang-Mongondow National Park, Indonesia

Meity Melani Mokoginta1, 2, Bobby Polii3, Mangku Purnomo4, Soemarno5

1Doctoral Program of Environmental Studies, University of Brawijaya, Indonesia

2Forestry Science Department, Fac. of Forestry, University of Dumoga, Kotamobagu, Indonesia

3Crop Production Department, Fac. of Agriculture, University of Sam Ratulangi, Indonesia

4Rural Sociology Department, Fac. of Agriculture, University of Brawijaya, Indonesia

5Soil Sciences Department, Fac. of Agriculture, University of Brawijaya, Indonesia

Correspondence to: Meity Melani Mokoginta, Doctoral Program of Environmental Studies, University of Brawijaya, Indonesia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

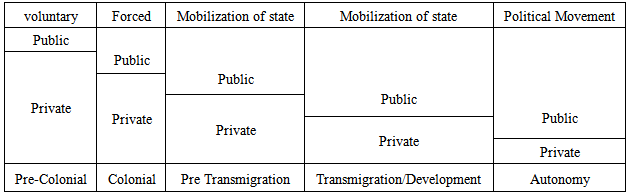

This study aims to determine transformation of cultural values of the Momosad in management of plantations and paddy fields in the Bolaang Mongondow, North Sulawesi. Results showed that there are three factors that drive transformation of Momosad cultural values, namely: (1) during the period of pre-transmigration this area is a small village and surrounded by natural-forest and only can be accessed with the cart path (a cow or horse carts). This area is inhabited by local tribes of Bolaang Mongondow and mingles with migrants from around the region. (2) During the transmigration period (1963-1980) the Dumoga area began to develop into paddy fields and rice producers, large stream flow capable of supporting irrigated paddy fields. Various ethnic groups living in this area, it makes this area is fatly developed, especially the patterns of agriculture and plantation management. Traditional farming evolved towards a more modern farming, land resources has good quality for agricultural cultivation, many migrants from other regions who worked as farm labourers and eventually settled in this area. (3) During Local autonomy Period (1999 - 2008) was characterized by the expansion of autonomous regions of North Bolaang Mongondow, Kotamobagu, South Bolaang Mongondow and East Bolaang Mongondow. At this time people's lives become increasingly more modern, and the transformation of Momosad cultural values become more significant in the management of agricultural land.

Keywords: In Momosad, Land management, Transformation

Cite this paper: Meity Melani Mokoginta, Bobby Polii, Mangku Purnomo, Soemarno, Transformation of Cultural Values of Momosad in Agriculture Land Management in the Buffer Zone of the Bolaang-Mongondow National Park, Indonesia, International Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. 4 No. 5, 2014, pp. 120-125. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20140405.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Developing countries are constantly striving to develop itself from a traditional society to the condition of a more advanced society. Therefore, processes of modernization are done to improve of the community’s quality. Integrated human resources development is one of the modern concepts of development towards more prosperous communities. The concept of this development can be carried out with focus on the sectors of agricultural land use, plantation and forestry [1-3] to support the other sectors.Economic structure the Bolaang Mongondow district showed a fairly good growth, particularly in the agricultural sector. This agricultural sector has always been the leading sector in the economic development of the region. Agricultural growth is related to the government's role in promoting a more modern agricultural system, application of Appropriate technologies, which is able to increase the production of food crops and plantation crops.Economic development able to encourage the processes of modernization and transformation of traditional rural communities, one of which is Momosad cultural with values of commitment, cooperation, dependability, and motivation. These values of Momosad aim to alleviate the heavy work and take a long time if done alone. By working together or mutual-help each other [4-6] any difficult job can be easily solved by involving the basic values of momosad and apply any indigenous knowledge [7-10].Social changes in rural agrarian society are characterized by the transformation of the values of local indigenous knowledge in managing farms (De Walt, 1994; Briggs, 2005). Transformation of agriculture in rural regions is a response to the demands of human-life and anticipation of a more complex and better human-life [11, 12]. Employment which was only using manpower, turns by using mechanical power, transport are faster, more open access to information and technologies, transport of goods can be done in a way that is fast and in more precise time [13]. All of these changes are apparently related to economic development targets [14].Modernization of society is a process of planned change of human-life in order to achieve a better state of society. These processes of community transformations are natural phenomenon and are supported by the engineered processes to create a more modern society and a better governance of human-life [15, 16]. Through these transformations, people can carry out development activities and enjoy their development results, as well as increased social mobility and greater political participation.Modernization of rural communities is affected by the level of management of common resources, which would have included any cooperation activities and an exchange of information and knowledge about management of agricultural lands and farming management [17-19]. The success of the changes in farming management in rural society is due to: (1) rural communities that have a strong tradition of cooperation and kin hipness so they easily share any information’s and knowledge, (2) the rules for rural communities in order to honour the next generations [20-22]. Integrated and sustainable agriculture systems are usually equipped with transport facilities and trading systems that allow mobility of agricultural products, agricultural inputs, credit and information of technologies [23, 24]. All of these have encouraged the development of farming systems that are more useful for farmers and rural society as a whole [25].Social change into the modernization of social life is strongly influenced by the acquisition of knowledge and the level of community education. The good education, training and extension can improve the acquisition of knowledge, skills and workforce competence and their working spirits. It has a long-term investment value for the community in improving productivity and increasing the capability of the community as a whole [26, 27]. Mastery of knowledge and skills by society is very important for the development and modernization of society [28]. Knowledge gained through education, training and daily experiences can be implemented to make changes in the appropriate technologies to improve the farming systems [29].Exchange of knowledge and cultural values can encourage rural communities to promote themselves like everyone else who has achieved better human life, so as to create a frame of thinking toward a better future world. People have become more dynamic, more active and creative, people are always trying to produce new discoveries and expect more prosperous life [30, 31].Modernization is an overall transformation of traditional society into the knowledge based society, more economically prosperous and politically more stable [32, 33]. Social organization and employment institutions have evolved toward a market system, so that the non-wage labour systems have been replaced by the more commercial systems, including the “borongan” wage system. The use of contract labour usually done by farmers in manure transporting, crop harvesting, and soil tillage. The farmers away from the city centre [34, 35] usually behave more subsistence; the cost of labour is less than the farmer closer to the city centre. The farmers who manage large farms usually have a higher income, and spend more on labour costs, and more commercial behaviour. Correspondingly, to foster the commercialization of farming is necessary to increase the economic scale of farm [36].Momosad activities are apparently still exists today, but has shown symptoms of transformation of traditional values, such as rewarding systems on services. Momosad in the past suggested that use of labour was not involving any wages, but rather with "obligation" to reply with labour. The current Momosad activities have implemented a reward system in the form of labour wages in the farm management activities. Farm management with the wage system is applicable in all villages in Boland Mongondow. This research was conducted in three villages, namely Mopugad, Mopuya and Doloduo. In these villages there are several tribes and different traditions, suggest the sufficient level of good agricultural economy, and being near-around the national park of Boland Mongondow. The process of traditional values transformation in the management of plantations and paddy rice farming in the buffer zone of the National Park is estimated ongoing.Based on the above discussion, this research examines factors that drive the transformation of the Momosad values in management of plantations and paddy farming in Boland Mongondow.

2. Research Method

- This study was conducted for 16 months (March 2012 - December 2013) in the Bolaang Mongondow, North Sulawesi. This study applied case study design, conducted a detailed analysis of the background conditions, people, stakeholder or actors of activities, as well as the places and events that are related to the research focus. This study focused on the transformation of cultural values of Momosad in farm management of plantations and paddy fields in Bolaang Mongondow. Focus of this study is set to (1) limit the scope of the research, (2) define effectively the inclusion and exclusion of information collected.Selection of key-informants and resource persons was conducted by purposive and snowball methods. In this snowball process, researchers will stop collecting information’s from key informants if: (1) according to researcher the needed information’s are enough, (2) if there has been a repetition of information’s by key informants regarding the same issue.The data and information’s includes places, actors, and activities. These dimensions are further detailed include: (a) a room or area, based on their physical appearances; (b) actors, all persons involved in the activities; (c) activities, what people do in a given situation; (d) object, that are contained in the location of activities, (e) actions, all activities performed by an individual person, (f) event or events, which is a series of activities carried out by individual people or groups of people, (g) time, which is the order of the activities, (h) purposes, which is something that is expected or will be achieved by individual people based on the meaning of his actions, and (I) feelings, that are emotions felt and expressed by someone Data and information’s are obtained from various sources, using multiple data collection techniques (triangulation). Gathering information’s from key informant are conducted continuously until saturated. Data analysis was also conducted simultaneously with data collection in the field.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. General Condition of the Bolaang Mongondow Region

- The agricultural sector is increasingly apparent as the largest contributor to GDP of Bolaang Mongondow district, so it is needed the special attention to the agricultural sector development in supporting the economic growth. Composition of the population in this district is dominated by the productive age group with the sex ratio of 108.47. This suggest that more men than women. Quantity of educational services in Bolaang Mongondow is sufficiently good, namely elementary schools, and the first high schools, while the second high schools are located in Kotamobagu.

3.2. Socio-economic Transformation in the North-Dumoga Village

- Agriculture in this region produces rice, production of rice in 2008 reached 60,682 ton, the average productivity is 5.37 ton / ha. The same year corn production reached 9,910 ton with an average productivity of 3.47 ton/ha. In addition to food crops, there are also plantation crop; 446.76 ton of coconut production; the production of cloves, nutmeg, coffee, cocoa and vanilla respectively 17.67 ton, 3.55 ton, 101.5 ton, 97.67 ton and 2.56 ton. There are also production of cinnamon, pecans and sugar-palm.Socio-economic life of the people in the village of Konarom, East Tapadaka, North Mopugad, and Doloduo are getting ahead with the Kosingolan reservoir as an irrigation water sources for rice production; construction of rural roads and sub-district roads, construction of traditional markets to support the rural economic development. Vegetable crop, fruit crop, other agricultural crops and plantation crops can be marketed every day or weekly, so as to supplement the family income. There are also retail-shops that sell the daily basic needs, and agricultural inputs store, such as seeds, fertilizers, pesticides and farm tools.The Dumoga and surrounding communities shows the values of modern lifestyle, despite his daily life was a farmer. They have a desire to move forward, have items of household equipment of good quality, have a car or motorcycle for those who can afford it, send their children to the good universities outside the region.

3.3. Pre-Transmigration Period

- In the pre-transmigration period, Momosad cultural values are still very significant, where the people from the Passi sub-district and around Kotamobagu come to the Dumoga in 1940 for clearing agricultural lands. Dumoga area at that time was already inhabited by a community group of Mongondow; they are instructed by the head of village to clear land as much as possible to supply their needs of foods. These people groups clear any forest lands and managing their lands by relying on Momosad culture, which in turn work-together; they help each other for cultivating their lands and managing their farm.On the basis of the social cohesiveness and solidarity, they are able to clear large tracts of forest-land and then divided by the same size on all members of the group. These communities eventually settled in the region Dumoga until now. These people of Bolaang Mongondow is at present residing in the Dumoga area, mingled with newcomers from Minahasa, Javanese and Balinese transmigrant, as well as urban communities of Gorontalo, Sanger, and Buggies.

3.4. Transmigration Period

- Dumoga area is a small village surrounded by jungle and not yet have an identity as an agricultural area. The significant development taking place since the arrival of Migrants to Bolaang Mongondow through transmigration program in 1963. This area has shown a significant progress, when compared with other areas that have the same potential of natural resources. This area has the high potential for a rice-field to produce rice and other food crops, and supported by the transmigrant of human resources (Javanese and Balinese) that are skilfulness in agricultural works. Local residents gradually integrate with migrants and absorb the knowledge and skills to manage their farm.

|

- The arrival of transmigrants led to changes in the values of the local culture, one of which was the desire of local communities to attempt in mastering any new knowledge and skills, working together with transmigrant community. Transmigrant community was able to "transfer" the knowledge and skills, and creating a high working-spirits among the local society to advance their farming becomes more productive [37, 38].Farming activities in the 1960s are still using a Momosad system or mutual cooperative system for the local community, these cultural systems began to decline in the 1980s. Momosad system have transformed in recent times into the labour-wage system, people do not have enough time to work-together in rotating system to cultivate their lands. Human needs of the local community have become increasingly varied in pursuing their retardation behind the transmigrant communities.Development of community economics and increasingly diverse needs of the communities, have encouraged the development of rural markets (traditional markets). This has contributed to increased agricultural production and impacted on improving local agricultural trade. The next development was the emergence of the borrowing and lending activities of agricultural capital, primary cooperation unit, and Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI).

3.5. Local Autonomy and Infrastructure Development Period

- In 2007, Bolaang Mongondow divided into three districts namely Bolaang Mongondow, The North Bolaang Mongondow and the Kotamobagu City; in 2008 The Bolaang Mongondow district was divided into two districts namely The South Bolaang Mongondow and The East Bolaang Mongondow. Similarly, the Dumoga Sub-district was divided into three sub-districts, namely The North Dumoga, The West Dumoga, and the East Dumoga.This autonomous region expansion suggested the positive impacts on the economic development of society and the transformation of cultural values of local communities. Life and people's behaviour becomes more "modern", imitative new things brought by the immigrant people. Become increasingly diverse needs of the community, and community service centres began to grow, such as schools, health centres, shops and markets in residential centres.Economic growth has driven the transformation of traditional values the social life; traditional values in agriculture began to be transformed into the more modern values or non traditional values. Instrastructure development to support economic development, such as rural roads, rural markets, rural-urban transportation facilities, have contributed to the exchange of information’s and innovation technologies to support the improvement of human lives. The process of transforming rural communities like this is a process of modernization [39], transformation of traditional agricultural systems towards the more commercial farming systems.

4. Conclusions

- The driving factors of transformations of Momosad cultural values in plantation management and rice field cultivation can be classified into three period, that are pre-transmigration period, transmigration period and regional autonomy period.Before the transmigration program, this region is a small village and surrounded by jungle-forest and streets accessible only by oxen-cart or horse-drawn carriage. This area is inhabited by indigenous communities Bolaang Mongondow and gradually began to arrive Minahasa ethnic in cooperation with the local people. In the course of time, the life of these two tribes has not shown a significant transformation of Momosad cultural values in their farming. In 1963 the transmigration program implemented in this area with a focus of agricultural development. Infrastructure development is focused on the agricultural irrigation systems and Kosinggolan-reservoir to support farming in paddy fields.The transmigration program has created the paddy field in the Dumoga region supported by the irrigation network and Kosinggolan reservoir in the Dumoga watershed. Migrant resident manage their lands for rice cultivation and has succeeded in making Dumoga region as the producer of rice. Various ethnic come to this region, it contributed to the regional development, the traditional farming has evolved into the more modern farming systems. The interaction between these various ethnics has led to the transformation of traditional cultural values Momosad enriched with the more advanced technologies in managing agriculture lands and plantations. Community economic development has also led to the development of traditional markets as the center of economic activities, such as the Doloduo market and the Imandi market.Expansion of the autonomous region in the district and sub-district levels has been encouraging people to behave more advanced in their agriculture and plantations, and constantly strive to improve their human life. This can be seen by the increasing growth of the local economy and development of traditional markets to support economic activities. In line with the increase in local economy, there has been transformation of any traditional cultural values; the traditional farming has evolved towards more modern farming, as well as the behaviour of rural communities in managing land resources suggesting any commercial orientation.The development and strengthening of local cultural values in improving human quality of life and regional development can be done by: (1) promoting cooperation and participation of the rural community and government to explore any potential of cultural values that can improve the sustainability of plantation lands and rice fields. (2) The cultural values of Momosad need to be explored and implemented in sustainable development of natural resources and environment. (3) Momosad cultural values are necessary to be implemented in any local regulations and encourage people to carry out the sustainable farm management in plantations and paddy lands. (4) Support of public policies to encourage community participation in implementing the cooperation values in the social, economic, and daily human life activities.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML