-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Sociology

p-ISSN: 2169-9704 e-ISSN: 2169-9739

2014; 4(2): 35-46

doi:10.5923/j.ijas.20140402.01

Gender, Health and Availability of Health Services in Jammu and Kashmir

Fayaz Ahmad Bhat1, Malik Yasir Ahmad2, Sadaf Rafiq Beg3

1Doctoral Candidate, Department of Sociology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, U.P., 202002, India

2Doctoral Candidate, Department of Economics, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, U.P., 202002, India

3Department of School Education, Government of Jammu and Kashmir, Jammu and Kashmir, 192101, India

Correspondence to: Fayaz Ahmad Bhat, Doctoral Candidate, Department of Sociology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, U.P., 202002, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Gender indicates the socio-cultural identification of man and woman and the way societies recognize them and disperse social role and responsibilities. However, this recognition often results in gender based discrimination. Health is an important condition of human life and a critically significant constituent of human capabilities that we have reason to value. WHO (World Health Organization) (1976) regards health as “state of complete mental, physical, and social well being and not just an absence of disease or infirmity”. Health care system refers to all the efforts, components, personnel, institutions, economic resources that a state or society devotes to health related problems. The importance of health as a basic human right has been recognized in United Nations Declaration which assigns health a prominent place in three of the eight goals, eight of the sixteen targets and eighteen of the forty eight indicators of the Millennium Development Goals. International Conference on Population and Development at Cairo in 1994 and Fourth World Conference of Women at Beijing in 1995 accepted that women’s health and reproductive rights are important indicators of women’s empowerment and quality of life. Despite wide spread agreement on the importance of health in general and women’s health in particular, many people, most of them women are deprived of this privilege. The paper aims to examine the extent of gender disparity in indicators of health status in the State of Jammu and Kashmir especially: food consumption and nutritional status; prevalence of anaemia, tuberculoses, reproductive health and maternal health of married women in the state. Further, attempt has been made to examine the availability of health care facilities in Jammu and Kashmir. The present paper is based on secondary data obtained from National Family Health Surveys, Census and supplemented with State Digest of Statistics and other government reports wherever necessary. Gender disparity in health status is amply clear as women in Jammu and Kashmir suffer discrimination in almost all indicators of health status and are at risk of further marginalization. Despite the expansion of the heath care infrastructure in the state, it has suffered from shortages in providing adequate health care facilities that are both qualitative and quantitative in nature. Such kind of situation necessitates gender specific policy formulation with their implementation in both letter and spirit.

Keywords: Gender, Health, NFHS-3(National Family Health Survey), Women, Status, Health system, Jammu, Kashmir

Cite this paper: Fayaz Ahmad Bhat, Malik Yasir Ahmad, Sadaf Rafiq Beg, Gender, Health and Availability of Health Services in Jammu and Kashmir, International Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2014, pp. 35-46. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20140402.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Gender is a nebulous concept. Although the term is widely used, there is no common understanding of its meaning, even among feminist scholars [1]. Gender is used to be seen as the “psychological, social and cultural aspects of maleness and femaleness [27]. This conception was found to be too narrow as it represented the characteristics taken on by males and females as they encountered social life and culture through socialization. A working definition of gender put forward by Wharton defines it [gender] as a “system of social practices; this system creates and maintains gender distinctions and it organizes relations of inequality on the basis of these distinctions”. According to this definition, gender has three main features: (1) gender is as much a process as a fixed state. i.e., it is being continuously produced and reproduced, (2) gender is not simply a characteristic of individuals, but occurs at all the levels of the social structure and (3) gender is important in organizing relations of inequality. In other words, gender involves creation of both differences and inequalities [56]. Gender unequal relations are social creations and perpetuated through socialization. To put it simply, gender indicates the socio-cultural identification of man and woman and the way societies recognize them and disperse social role and responsibilities. However, this recognition often results in gender based discrimination. This discrimination is noticed in every aspect of women’s life including health. Health is an important condition of human life and a critically significant constituent of human capabilities that we have reason to value [46]. WHO (World Health Organization) defines health as “state of complete mental, physical, and social well-being and not just an absence of disease or infirmity”. In other words it regards health as simply not the absence of disease but to a state of well-being, wholeness, harmony, equilibrium and quality or fullness of life. Peter however argues that such an extensive definition of health by WHO has a problem of its own, as it is not clear how health is distinct from other components of well being. This definition also does not allow the possibility that some well-being may be achieved when health is bad or health may be good and well-being low and this definition does not make it clear how well-being can be defined in a way consistent with plurality of conceptions of good health [38]. A component of autonomy has been added to the definition of health by WHO as mentioned by Smith et. al.. They argued that health can be regarded as an umbrella term that encompasses various other states such as health status, functional status, health related quality of life and quality of life [50]. Health has been regarded as a special good throughout the ages because: (i) it is a direct constituent of human well being, and; (ii) it is a pre-requisite of a person’s functioning as an agent in the society [3]. In the words of Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, health, like education, is among the basic capabilities that gives value to human life [47]. It contributes to both social and economic prosperity. Health in itself is of great value as it enables people to enjoy their potential as human beings. Therefore, it is important to protect health through health care besides other means such as socioeconomic development. Better health translates into greater and more equitably distributed wealth by building human and social capital and increasing productivity [58], though the concept of good health is relative. Health status is multidimensional in nature and difficult to measure precisely. Health status includes a set of indicators used to provide important health and health-related data regarding incidence and prevalence of disease, health risks and performance of health systems. It is captured through a range of indicators such as mortality, morbidity, anthropometric measures, nutritional status or calorie intake, and life expectancy at birth. Besides, it provides an overview of reproductive and child health as well as disability prevailing in the country. Among these, mortality and life expectancy at birth are widely used to measure the health status of a population, as they are easily observed, objective and less prone to measurement errors [13]. Any definition of the term ‘health care’ is liable to be problematic because its boundaries are ill-defined and disputed. While it is easy to list services and procedures universally agreed to be health care, however organizing public systems of care demands the allocation of resources and responsibility between organizations, in ways that enable social policy to be effectively implemented [42]. Health care is ‘any activity that is intended to improve the state of physical, mental or social function for one or more people’. It includes a wide spectrum of activities such as health promotion, disease prevention, curative care and rehabilitation, long-term and palliative care. It expands beyond the formal sector into the informal sector and also includes the availability of health care for lay people and the extent of health care needed from professionals [50]. Ring’s definition of health care is much broader and he defines health care as ‘any individual or population-based intervention seeking to remedy the causes and effects of physical or mental ill-health, or injury, and /or to promote good health. Society recognizes these aims as valid ends in themselves’ [42]. “Health system” refers to all the efforts, components, personnel, institutions, economic resources that a state or society devotes to health related problems [2]. WHO (World Health Organization) has pointed out that the term may be used for “all the activities whose primary objective is to promote, restore or maintain health” [59]. A health system has three main objectives: (i) improve the health status of the population; (ii) protection of the people from the financial risks of the health problems and; (iii) respond to the citizens demands and needs (World Bank, 2002) [60]. Health care system covers not merely medical care but also all aspects of preventive care too. Nor can it be limited to care rendered by or financed out of public expenditure within the government sector alone but must include incentives and disincentives for self-care and care paid or by private citizens to get over ill health. Smith et. al. gave the four dimensions for evaluating health care: (i) Effectiveness: It explains the benefits of health services measured by improvements in health in real population. Sometimes benefits of health care are described in terms of efficacy which describes benefits obtainable from an intervention under ideal conditions such as in a specialist centre; (ii) Efficiency: It relates the cost of an intervention to the benefits obtained. However efficiency is also used to refer to increased productivity; (iii) Humanity: It describes the social, psychological and ethical acceptability of a treatment that people receive from health care intervention, and; (iv) Equity: This refers to the distribution of health services fairly among the groups or individuals. These four dimensions are used to find whether an intervention is appropriate for a population or not but an intervention is rarely perfect in all four dimensions [50]. The importance of health as a basic human right has been recognized in United Nations Declaration which assigns health a prominent place in three of the eight goals, eight of the sixteen targets and eighteen of the forty eight indicators of the Millennium Development Goals [20]. Women’s health in general and reproductive health in particular was a neglected area in health care. These issues came into limelight after the International Conference on Population and Development held at Cairo, Egypt in September 1994 and the Fourth World Conference on Women, held in Beijing in September 1995. Both these conferences placed immense importance on women's health, empowerment and reproductive rights. Not discounting the importance of health needs and health status of men, the fact remains that over a lifetime the health of women is usually worse than that of men. Moreover, certain health problems are more prevalent among women than among men and certain health problems are unique to women/affect women differently than men. Furthermore, some environmental problems have a disproportionate impact on women compared to the males. Despite widespread agreement on the importance of health in general and women’s health in particular, many people, most of them women are deprived of this privilege. Living under the control of first their fathers, then their husbands, and finally their sons, women in South Asia are excluded from decision making, have limited access to and control over resources, are restricted in their mobility, and are often under threat of violence from male relatives. Individual and societal beliefs mean that women are disadvantaged with regard to health and health care. Most of the evidence shows that gender inequalities have led to a systematic devaluing and neglect of women’s health [14]. The difference between genders is more keenly felt in patriarchal societies like India where women are relegated to inferior status in every aspect of life including health. The health of Indian women is intrinsically linked to their status in society. It has often been found that Indian women’s family contributions are often overlooked and they are likely to be regarded as an economic burden, especially in rural areas. This attitude has a negative impact on their health status. Poor health has repercussions not only for women, but also for their children and other family members [43]. India’s low sex ratio is “the starkest index of the oppression of women” and the higher death rate among women is because girls are given less food and health care [34] which has contributed to their higher mortality [51]. India is one of the few countries in the world where women and men have nearly the same life expectancy at birth. This suggests that there are systematic problems with women’s health as the typical female advantage in life expectancy is not seen in India. Indian women have high mortality rates, particularly during childhood and in their reproductive years. Socio-economic and educational marginalization of women affects their health status. Women in poor health are more likely to give birth to low-weight infants. They also are less likely to be able to provide food and adequate care for their children. Finally, a woman’s health affects the household’s economic well-being, as a woman in poor health will be less productive in the labour force [54]. Traditionally, it is argued that ideal sex ratio should be skewed more towards females than males as women are physiologically equipped to live longer than men. However, there is a strong son preference in India, as sons are expected to care for parents as they age. Sons are associated with prestige in the community and social power. Through sons, a family can perpetuate the family line and ensure the continuity of the family name. Furthermore, any lands given to a son will most likely remain within the family [6]. In agrarian societies, sons are desirable as hands to work in the field, and small towns value sons as an asset in the fight against the “encroaching urban society [28]. In addition, many couples depend on a son to care for them in their old age and assist in the financial stability of the family [48]. This son preference, along with high dowry costs for daughters, sometimes results in the mistreatment of daughters. Committee on the Status of Women in its landmark report concluded that “an increase in the neglect of female lives as an expendable asset” is “the only reasonable explanation for the declining sex ratio observed to persist over several decades” [10]. Studies across India have found that boys are much more likely than girls to be taken to a health facility when sick [11]. Boys had higher immunization rates than girls in all states except Goa and Karnataka, although the extent of this difference varied across states. Similarly, girls are more likely to be malnourished than boys in both the northern and southern states [4]. Gender disparities in nutrition are evident from infancy to adulthood. Gender differentials in nutritional status are documented during infancy, with discriminatory breastfeeding and supplementation practices. Infant girls are breastfed less frequently, for shorter duration, and over shorter periods than boys [11]. The excess mortality of females is believed to result from ‘discrimination against females’ that include less favorable access to food and health care for females ([11] [31]). Poor health of Indian women is also the outcome of discriminatory treatment that girls and women receive as compared to boys and men in their families. Males are fed first and better than females who are fed last and less. It threatens their survival as well as that of their children. Presumably, the negative effects of malnutrition among women are further exacerbated or compounded by heavy work demands, poverty, childbearing and rearing, and by their special nutritional needs, eventually culminating into increased susceptibility to illness and consequent higher mortality [29]. Women's reproductive biology, combined with their lower socioeconomic status, result in women bearing the greater burden from unsafe sex which includes both infections and the complications of unwanted pregnancy. Girls who are fed inadequately during childhood may have stunted growth, leading to higher risks of complications during and following childbirth. Similarly, sexual abuse during childhood increases the likelihood of mental depression in later years, and repeated reproductive tract infections can lead to infertility [52]. Women's risk of premature death and disability is highest during their reproductive years. Malnutrition, frequent pregnancies, unsafe abortions, RTI and STI, all combine to keep the maternal mortality ratio in India among the highest globally. Keeping foregoing discussion in view, this paper aims to examine the extent of gender based discrimination in indicators of health status and the availability of health care facilities in Jammu and Kashmir. The present paper is based on secondary sources and is descriptive and analytical in nature. Gender disparity in health status is amply clear as women in Jammu and Kashmir suffer discrimination in almost all indicators of health status and are at risk of further marginalization. Despite the expansion of the heath care infrastructure in the state, it has suffered from shortages in providing adequate health care facilities that are both qualitative and quantitative in nature. Such kind of situation necessitates gender specific policy formulation with their implementation in letter and spirit.

2. Objectives and Methodology

- There are number of parameters which are used to assess the general health situation such as sex ratio, life expectancy and crude death rates, infant mortality rate, indicators of nutritional status, age at marriage, reproductive health and maternal health. Women’s health beyond reproduction covers menopause, domestic violence and dowry as well. However, in the present study, an attempt has been made to: examine the indicators of women’s health status such as sex ratio, IMR in general, food consumption and malnutrition, reproductive health and status of maternal health of married women in Jammu and Kashmir. The paper also intends to bring into lime light the existing condition of health care system in Jammu and Kashmir.The present paper is based on secondary sources. Data was extracted from NFHS-3, Census, Family Welfare Statistics, SRS Bulletin, and DLHS-3 to collect information on the parameters of both (married) women’s health of age 15-49 age as well as health care system in Jammu and Kashmir. This is also supplemented with State Digest of Statistics and other government reports wherever necessary.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Gender Discrimination in Health Status in Jammu and Kashmir

- It can be rightly argued that women’s lived experiences as gendered beings result in multiple and, significantly, interrelated health needs. At any given time, the health needs of men and women are different where women with their biologically and culturally assigned roles have more health care needs than men. The multiple burdens of ‘production and reproduction’ borne from a position of disadvantage has telling consequences on women’s well-being. To elaborate, biologically they bear the burden of reproduction. Women alone have to go through all the problems and discomforts related to pregnancy and delivery. Culturally, in India, women are expected to be subservient to the male members of the household and work for the latter’s happiness and satisfaction. Further, society expects them to play a very important role in providing informal health care to all the members of the family. It is their responsibility to rear children on healthy lines, teach them health habits, prepare and select the family's food, and care for the young, the sick, the aged and the disabled. Four critical areas of women’s health and physical wellbeing deserve special attention: discrimination against girls resulting in higher female mortality; poor nutrition; poor reproductive health; and lower use of medical services when sick. Poor health has repercussions not only for women but also their families. Women in poor health are more likely to give birth to low weight infants. They also are less likely to be able to provide food and adequate care for their children. Finally, a woman’s health affects the household economic well-being, as a woman in poor health will be less productive in the labour force. Because of the wide variation in cultures, religions, and levels of development among the different regions of India, it is not surprising that women’s health also varies greatly from state to state. The analysis of various parameters of women’s health in Jammu and Kashmir confirms that women suffer discrimination in almost all indicators of health status and are at risk of further marginalization.

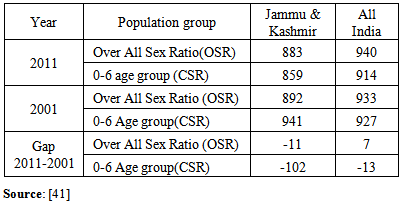

3.1.1. Sex Ratio

- Sex ratio, defined as number of females per 1000 males is a powerful indicator of the social health of any society and is a sensitive indicator of women’s status as it conveys a great deal about the state of gender relations [36] especially in terms of women’s health and position in any society [8]. In this paper two types of sex ratios will be examined: (i) sex ratio of the total population or overall sex ratio (OSR), and (ii) sex ratio for the children aged 0-6 years or child sex ratio (CSR). Having a glance at Table 1 makes it clear that the sex ratio in terms of both OSR and CSR at the state as well at national level is favouring males. What is more perturbing is the sudden decline in child sex ratio (CSR) which declined from 941 in 2001 census to 859 in 2011 census in Jammu and Kashmir against 927 to 914 in India during the same decade. The inferences drawn from the analysis of census figures of sex ratio reveals that social health of society is not in favour of women and therefore it is not wrong to say that women’s health and position is poor both at national, i.e., Indian as well as state level.

|

3.1.2. Infant Mortality Rate (IMR)

- Infant mortality rate (IMR)-number of live-born babies dying prior to the 364th completed day of life per 1000 live births-is regarded as vital sign of the health of a society, reflecting as it does the care given to the expectant mothers and their newborn. The single best intervention that any government can make to improve the health of its population is the provision of universal, free care for mother-to-be and new-born infants. It is very sensitive to the factors of accessibility and quality of health care besides being associated with education and economic development [49]. Analysis of figures for IMR as given in Table 2 shows that IMR for boy male and female child is lower in the state against the national figures. However, it can be noted as given in Table 2 that IMR for female child is higher than male child in India as well as in Jammu and Kashmir. Such kind of situation necessitates the timely intervention of government and non-government organization to provide accessibility and quality health care to both mother and child.

|

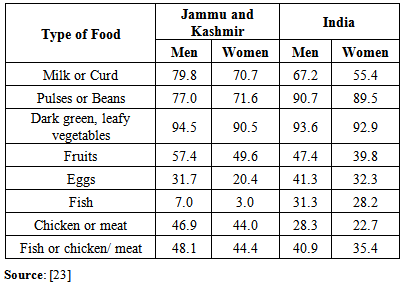

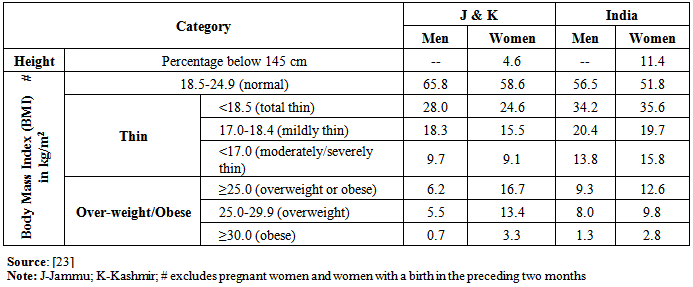

3.1.3. Nutritional Status

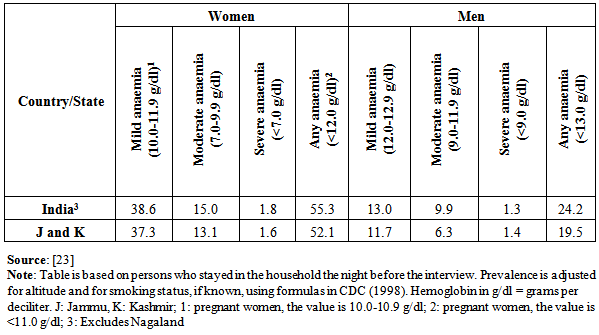

- Nutrition-food and liquids that sustain life is a determinant of health because well balanced diet increases the body’s resistance to infection, thus warding off a host of infections as well as helping the body fight existing infection. Nutritional deficits and their contribution to disease and death are a product of not of any worldwide shortage of food, but of the politics of its distribution [57]. The consumption of a wide variety of nutritious foods is important for women’s and men’s health. Adequate amounts of protein, fat, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals are required for a well-balanced diet [23]. Malnutrition refers to lack of food of sufficient quality to maintain a healthy life [57]. In other words, it is a situation where the diet is either deficient in some nutrients or some nutrients are in excess, lacking or in wrong proportion change language. Simply put, we can categorize it to be under-nutrition and over-nutrition. One of the major causes for malnutrition in India is gender inequality. Due to the low social status of Indian women, their diet often lacks in both quality and quantity. These conditions not only complicate childbearing and result in maternal and infant deaths, maternal depletion, and low birth weight infants, but also severely affect women’s productivity and quality of life. Nutritional deficiency can manifest in an array of disorders like protein energy malnutrition, night blindness, iodine deficiency disorders, anemia, stunting, low Body Mass Index and low birth weight.Table 3 gives a comprehensive picture of food consumption across gender in India and Jammu and Kashmir. The analysis of the data reveals the gender disparity in food consumption exists at both state and national level. The consumption of dark green leafy vegetables at least once a week is higher and that of Fish is lower among women in the state as well as in India. Women in comparison to men in Jammu and Kashmir report relatively low consumption of food items which are rich in protein content such as fish, egg, milk or curd and pulses or beans.

|

|

|

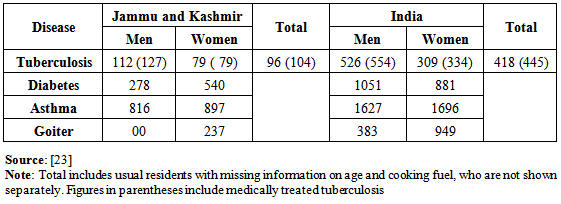

3.2. Gender and Illness: Tuberculosis, Diabetes, Asthma and Goitre

- Tuberculosis (TB) has re-emerged as a major public health problem in many parts of the world, often as a concomitant illness to HIV/AIDS. Tuberculosis-is a bacterium borne disease-once known as the ‘White Plague’, is contagious and spreads through droplets that can travel through the air when a person with the infection coughs, talks, or sneezes. This bacterium eats away at lung tissues until they no longer function. TB most affects those who have the fewest physical and financial resources to combat it ( [22] [23]).Tables 6 present the prevalence of TB, diabetes, asthma and goiter in Jammu and Kashmir as well as in India. Men are much more likely than women to have tuberculosis in both Jammu and Kashmir as well as in India whereas in case of asthma and goiter, it is women who outnumber men in Indian as well as in Jammu and Kashmir. Furthermore, women in state are more diabetic then men whereas in case of India it is vice-versa. Such kind of situation points to how much functional is the existing health care system is in the state as well as in the country and therefore necessitates immediate intervention and proper research to look into the factors responsible for it.

|

3.3. Reproductive Health

- Reproductive health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in all matters relating to the reproductive system and to its functions and processes [17]. The concept of reproductive health gained currency in the 1980s as a symbol of a fresh perspective on women’s rights and family planning. The premise of this perspective is the principal that every woman has a right to reproductive health that is to regulate her fertility safely and effectively; to understand and enjoy her own sexuality; to remain free of disease, disability, or death associated with her sexuality and reproduction; and to bear and rear healthy children ( [16] cited in [12]). In the present study, only three parameters of reproductive health namely: reproductive track/ sexually transmitted infections and maternal health are discussed.

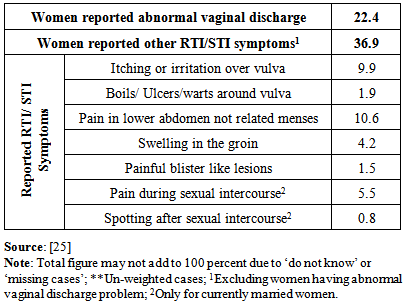

3.3.1. Reproductive Tract Infections/Sexually Transmitted Infections (RTIs/STIs)

- Many women and men suffer from reproductive tract infections (RTIs), including sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Reproductive tract infections (RTIs) are syndromes that cause acute physical discomfort, personal embarrassment and lost economic productivity ([39] [35]). Women are known to accept RTIs such as: vaginal discharge, itching, ulcers, bleeding, and discomfort as an inevitable part of their womanhood something to be tolerated, along with other reproductive health problems such as sexual abuse, menstrual difficulties, contraceptive side-effects, miscarriages, stillbirths and potentially life-threatening clandestine abortions and childbirth’s. In India, married women are reluctant to seek medical treatment for these infections because of lack of privacy, lack of female doctor at the health facility, the cost of treatment and their subordinate social status ([9] [26] [44] [5] [40]). Furthermore, women, more so than men, tend to regard RTI symptoms as normal discomfort and therefore often do not seek treatment ([7] [32] [40]). The consequence of RTIs/STDs are numerous and potentially distressing. These include post abortal and puerperal sepsis, ectopic pregnancy, fetal and perinatal death, cervical cancer, infertility, chronic physical pain, emotional distress and social rejection of women [15].Table 7 provides information about the prevalence of RTIs among the ever married women aged 15-49 years in Jammu and Kashmir. Analysis of the data reveals that 22.4 percent have experienced abnormal vaginal discharge. Among the women who had reported having symptoms of RTIs/STIs (37 percent), it is the pain in lower abdomen not related to period which is reported by as high as 10.6 percent of women and spotting after sexual act is reported by as low as 0.8 percent of women. This needs immediate interventions on the part of government as well as non-government agencies including civil society as such suffering of women has very negative consequences on women’s health in future. Further, efforts at the individual, community as well as at society level should be made by males who need to be cordial in helping in females family members to report such problems as well as to provide assistance for the treatment of such infections.

|

3.3.2. Menstruation Related Problems

- Menstrual related problems are generally perceived as only minor health concern and thus irrelevant to the public health agenda particularly for women in developing countries. Menstruation is a normal physiological phenomenon for females indicating her capability of procreation. Menstrual cycle is normal physiological process that is characterized by periodic and cyclic shedding of endometrium accompanied by loss of blood which is a vital sign for assessment of normal development in adolescent and young girls [33]. However this normal phenomenon or process is not easy one. It is often associated with some degree of sufferings and embarrassment mainly because of a sense of hesitation and to an extent, because of financial constraints. It is a common observation that every woman does experience one or other type of menstrual problems/ symptoms in her life time [55]. These symptoms include fatigue, bloating, irritability, depression, bothersome cramping or heavy bleeding and, for a small fraction of women, may be severe enough to interfere with social or occupational functioning [37]. However in the present study, the menstrual related problems are dealt and are highlighted in the Table 8. Having a glance at the table 8 reveals that fact that among ever married women aged between 15-49 years, 30.9 percent have experienced one or the other menstruation related problems. Further analysis of the figures related to reported symptoms shows that the problems of painful periods is reported by highest percentage of women (78.2 percent) followed by blood clots/excessive bleeding (18.8 percent), irregular periods (16.9 percent), prolonged bleeding (12.9 percent), scanty bleeding (5.7 percent), no periods (3.3 percent), frequent or short periods (3.0 percent) and inter-menstrual bleeding (2.0 percent) in Jammu & Kashmir. The problems mentioned above have serious repercussions not only on health status of women but also on social, psychological, economic, and educational sphere as they feel embarrassed and this hampers their full participation in these spheres.

|

4. Health Care Services in Jammu and Kashmir

- Health care is any activity that is intended to improve the state of physical, mental or social function for one or more people at acceptable cost. The goal of health care infrastructure is to improve the health system to provide better quality for same cost, or increased quality at decreased cost for most interactions [45]. Access to health care is well recognized as a basic right of the people. This sector assumes focus for reaping the demographic dividend having healthy productive workforce and general welfare [20]. Realizing the importance of health care, the State has been providing necessary policy frame work, up-scaling health institutions, engaging additional manpower and allocating resources for medical equipment for improving the delivery of public health care services [21]. The State is committed to make every effort to safeguard and promote health of the people, and ensure widespread and efficient medical services throughout the State. Keeping in view the importance of health care which has direct correlation with the welfare of the people, the State has been focusing on infrastructural facilities, availability of manpower, and medical equipment besides undertaking health sector reforms as per the changing needs. As a result of measures initiated, the public health system of the state has witnessed both quantitative and qualitative improvements over the years. Presently, Government institutions are providing health care services in various specialized and super specialty disciplines against negligible fee. Free medicines are also being provided against available budgetary provisions [20]. The state is trying hard to bring qualitative improvement in the health services through strengthening of physical facilities like provision of essential equipment, supply of essential drugs and consumables, construction of building and staff quarters, filling up of vacant posts of medical and paramedical staff and in-service training of staff.

4.1. Outlay and Expenditure on Health Care Services

- The State government realized that for bringing the holistic development in the health of the citizens of the state as well as that of women, development in health care system is a prerequisite. Table 11 shows the total outlay and expenditure on health allocated in the year 2007-08 and 2008-09. The emphasis on health care services is also reflected in the trend of expenditure on social services and health services by the government. However it is surprising that the share in state budget for social and health sector decreased from Rs. 1196 .62 and Rs. 272.97 Crore in year 2007-08 to Rs.1189.15 and Rs. 203.40 Crore respectively in 2008-09. Same is true in case of per capita expenditure on health. This is cause of concern as it will bring into standstill the expansion and growth of health care system.

|

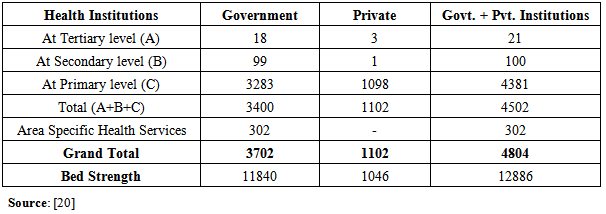

4.2. Health Care Institutions, Bed Strength and Medical Personal in Jammu and Kashmir

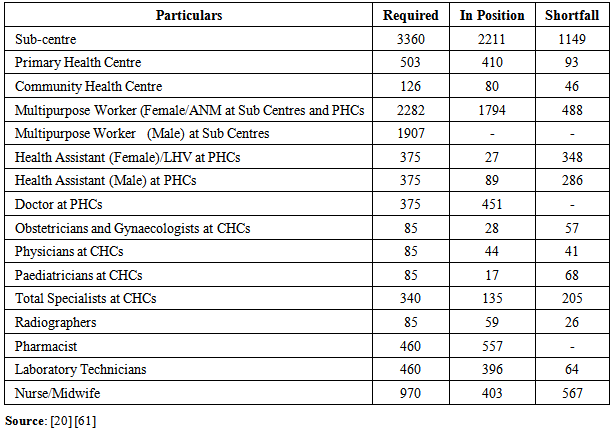

- According to the 2011 Provisional Census figures, the total population of the state is 1, 25, 48,926 persons comprising 66, 65,561 males and 58, 83,365 females distributed over 22 districts, 82 tehsils, 142 Community Development Blocks and 4136 Panchayats, 6652 villages, 68 urban areas and 7 urban agglomerations [19]. Looking after the health of people of state, the government provides healthcare facilities through a large number and a variety of institutions—dispensaries, primary healthcare institutions, small hospitals providing specialist services, large hospitals providing tertiary care, medical colleges, paramedic training schools, laboratories, etc. It can be seen from the Table that it is the public sector who is forerunner in establishing health institutions and providing bed strength. However, the role of private sector cannot be ignored as it has been toiling hard in providing healthcare at primary level.The state has institutions spread throughout its length and breadth. The total number of the institutions of healthcare in the state as given in Table 10 is 4804 comprising of 3702 government and 1102 private institutions. Similarly the total number of beds in these institutions is 12886 in which share of governmental sector is higher (11840 beds) than that of private sector (1046).

|

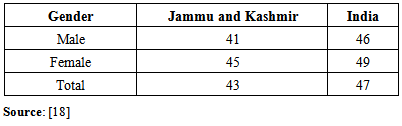

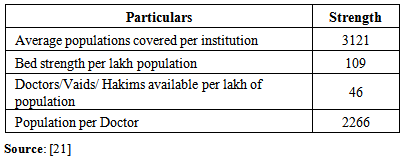

4.3. Population Covered and Projected Deficit in Health Care Infrastructure

- If one has to assess how much strong health care infrastructure of any country or state is, that can be done by analyzing the average population covered by institutions, availability of beds per lack population and doctors per lakh population and population per doctor. A glance at the figures as given in Table 11 shows that the average population covered per institution is 3121, bed strength per lakh population is 109, doctors/vaids/hakims available per lakh population is 46 and population per doctor has been calculated as 2266 persons.

|

|

5. Conclusions

- Although there is widespread agreement on the importance of health in general and women’s health in particular, many people, most of them women are deprived of this privilege. It is women who bear the brunt of gender discrimination in the forms such as: declining female population, higher female IMR, low consumption of protein rich diet by women, suffer from malnutrition, anemia, diabetes, goiter and asthma. In addition to this women are vulnerable to reproductive tract infections and problems related to menstruation. Despite the fact that State government in collaboration with Central government has introduced so many programmes and policies but it has failed to deliver what it promised for providing health care facilities to all, especially women. The general health problems of women are aggravated further by the ongoing conflict in the state as they become victims of direct or indirect violence. Though there has been substantial expansion of healthcare infrastructure and facilities by the state government along the private sector, but it has been unable to fulfill the growing demand owing to several factors viz., topography, armed conflict, deficit of healthcare infrastructure in terms of both quality and quantity. There is therefore need for further expansion of healthcare infrastructure keeping in mind the gender specific health needs not only in terms of quantity but also in quality by government as well as by private sector. Involvement of the third sector, i.e., non-governmental organisations is also very important in generating awareness among masses regarding the importance of women’s health, highlighting gender specific health problems and assisting people especially women how to make full use of healthcare facilities so as to achieve the value of ‘being healthy’ because health is what the Noble Laureate Amartya Sen has called “an important condition of human life and a critically significant constituent of human capabilities that we have reason to value.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Paper presented in International Seminar on “Gender Justice: A Way Forward” organized by Department of Law, School of Legal Studies, Central University of Kashmir (October, 23-24, 2013).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML