-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Sociology

p-ISSN: 2169-9704 e-ISSN: 2169-9739

2013; 3(3): 42-58

doi:10.5923/j.ijas.20130303.02

Public Perceptions of Income Inequality and Popular Distributive Justice Sentiments in Korea

Jeong Won Choi

Department of Sociology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, 61801, USA

Correspondence to: Jeong Won Choi, Department of Sociology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, 61801, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This research empirically and comparatively investigated the Korean public’s perceptions of and norms about economic inequality, using data from the 1999 ISSP module on social inequality. Unlike the conventional wisdom of favorable public views, in both normative and perceptual terms, of economic inequality in advanced Western capitalist societies in general, my analysis demonstrated that Koreans not only retain much stronger egalitarian strain in their scheme of distributive justice than other OECD counterparts do, but also perceive more threats of large income inequality than other OECD counterparts do, despite the fact that Korea’s income distribution is in fact more equitable than many of other OECD counterparts’. Drawing upon the ideology thesis, I hypothesized that the inflated public perceptions of large income inequality in Korea are facilitated by Koreans’ strong commitment to egalitarian distributive justice, and tested its validity comparatively against Korea and other OECD countries. My analysis showed that Korea, compared to many of their OECD counterparts, showed a better fit to this test.

Keywords: Income Inequality, Public Perceptions, Distributive Justice

Cite this paper: Jeong Won Choi, Public Perceptions of Income Inequality and Popular Distributive Justice Sentiments in Korea, International Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. 3 No. 3, 2013, pp. 42-58. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20130303.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

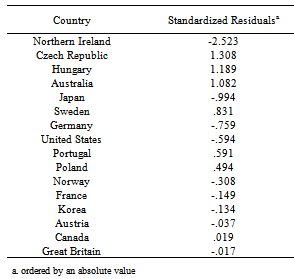

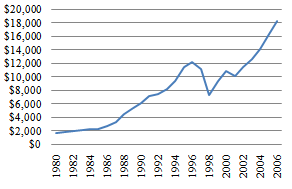

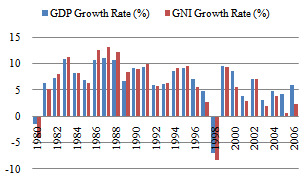

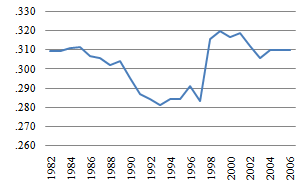

- Economic inequality is now a marked feature of the socio-economic structure of capitalist societies. Income and asset stratifications stand out, and division between the winners and the losers in the market has become more manifest than ever. As Frank and Cook criticized[1], as people vie for fewer and bigger prizes in the market, more economic waste, inequality, and impoverished cultural life are brought to a majority in society while the fruits of competition return only to the few—hence, the advent of a ‘winner-take-all-society.’However, opinion research in the West has revealed rather favorable public attitudes toward the legitimacy of economic inequality in the market. That is, citizens in advanced capitalist economies in general view inequality as just and legitimate, and they principally concede its necessity for the greater social good. In America, for instance, people have been found to support merit-based unequal distributions over equality and need, and to stigmatize the poor for their plight, attributing their poverty to their moral defects such as incompetence and laziness[2-9]. According to Lane[4], such positive attitudes toward the capitalist socioeconomic order in America is rooted in Americans’ fundamentalcommitments to market justice. Market justice, by definition, is an inter-related system of norms of and beliefs about the economic order that serves to legitimize capitalism. Lane highlighted that Americans value earned deserts as a critical market justice norm over other values such as equality and need because they judge economic fairness in terms of the process of allocation, not the shape of outcomes per se. In other words, in their assessment of market fairness, Americans in general are concerned not so much about macro (or social) justice, namely, the outcome of social distribution as a whole, as about micro (or individual) justice, namely, the equity of individual reward. Rainwater[10], likewise, discovered a similar justice orientation in his study. He said:A few respondents offered this[everyone should have about the same level of resources] as their understanding of the American equality value. When they did so, it was often more to disagree with it than to endorse it. In general, the idea of essentially equal distribution of resources does not seem to be attractive to most people. (P. 168) The defense of capitalism, namely, the principal commitment to market justice norms and beliefs, according to Lane, is not unique to the American public. He argued for its universal application to other capitalist societies as well: he argued that any rational human being would accept unequal distribution due to market processes as more just than distribution based on political justice, namely equality and need, because of the genius of the market. That is, the market, unlike politics, creates the sense of controlling one’s own destiny for people, and this leads them to sense more injustice in the polity than injustice in the market. Therefore, preference for market justice over political justice is a universal psychological reaction that any rational person can experience. In the same vein, Della Fave[11-14] argued for the common legitimating process of social stratification in capitalist societies. According to him, in capitalist societies, the wealthy come to be seen as deserving of their privilege through a process of status attribution. By self-comparison to the wealthy, the poor subsequently come to see their own status as equitable as well. According to Lerner[15], people are fundamentally motivated to believe that they live in a just world where people get what they deserve. Such beliefs, also known as the Just World Hypothesis, he argued, illusory as they may be, lead people to convince themselves that beneficiaries inevitably deserve their benefits and victims their suffering.As the foregoing theories suggest, if citizens in the capitalist countries indeed share a great cognitive commonality in the way they accept inequality as desirable, prefer earned deserts over equality and need, and justify the privileges of the wealthy as deserved, then it is fair to speculate that Koreans’ beliefs about and norms of inequality will not differ fundamentally from their Western counterparts’. Late-comer capitalist state as it may be, at least prior to the 1997 financial crisis, Korea was renowned as a model case of miraculous capitalist development [16-21]. It was miraculous in that not only was a successful and rapid capitalist adjustment achieved following the devastation of the Korean War in the 1950s, but also such rapid industrialization was achieved in the absence of serious economic inequality. Such a dual achievement of Korea—namely, rapid economic expansion and an equal distribution of income—as the World Bank[22] acknowledged, was an exceptional experience for a developing country. The following figures support this point. According to Figures 1 and 2, not only did the GNI per capita increase by nearly seven times, from $1,645 in 1980 to $12,197 in 1996, but also both the GDP and GNI increased significantly each year, growing by averages of 7.76% and 7.99% per year, respectively. More importantly, this expansion of the macro-economy was not accompanied by an immediate increase in income inequality. As Figure 3 indicates, Korea’s Gini coefficient during the same period revealed an overall declining pattern. Looking at the changes between 1982 and 1997, except for during the first half of the 1980s, the coefficient constantly declined over the following years and dipped to a low of .281 in 1993. While this downturn was shortly interrupted by a slight increase over the following three years, .284 in 1994 and 1995, and .291 in 1996, the coefficient again dipped to a low of .283 in 1997.Behind the successful and swift economic success of Korea, one is tempted to assume, lie corresponding favorable norms of and beliefs about inequality in public opinion such as the preference for earned deserts over equality, a high level of perceived legitimacy of economic system, and the legitimization of economic inequality as in the West. However, early literature on Korea written by Western scholars provides rather different perspectives on this subject matter. The Korean public, according to their notes, were vastly concerned about and critical of economic inequality even when the Korean economy was renowned for keeping economic inequality under control as it did in the 1980s, not to mention when the Korean economy fell into the mire after the 1997 financial crisis, and, more importantly, such public anxiety easily was transformed into social hostility toward the wealthy.

| Figure 1. GNI per capita of Korea |

| Figure 2. GDP and GNI Growth Rates of Korea |

| Figure 3. Gini Coefficient of Korea |

2. Theory: Ideology Thesis

- The influence of justice ideologies or norms on the perception of economic inequality has interested many students of social justice study[3, 26-32]. The key premise of their initiative is that the subjective perception of inequality may have less to do with objective social facts, but more with value systems or ideologies regarding social justice that coexist with the structural conditions. Beyond actual inequality, they assume, other factors—in this case, the dominant justice ideology of society—would play a crucial role in shaping these perceptions. Of most relevance to the discussion is the dominant ideology thesis[33], which sheds light on ideology as the macro-level determinant of beliefs about inequality. The thesis was originally devised in Marxist discourse in order to explain how a dominant class of a society maintains both material and mental dominance over the subordinated class through the control of ideological production. The thesis assumed that through its control of ideological production, the dominant class is able to supervise the construction of a set of coherent beliefs. These dominant beliefs of the dominant class are more powerful, dense, and coherent than those of the subordinate classes. The dominant ideology penetrates the consciousness of the working class, because the working class comes to see and to experience reality through the conceptual categories of the dominant class. Yet, the notion of dominant ideology and its usage has been questioned in that, as critics have argued[33-35], the ideology of the ruling class has been, from a historical point of view, opposed by the class interests of the subordinate class, and, more importantly, it has not been available to the subordinate classes because it simply was not relevant to the everyday lives of the subordinated. The purpose of the ruling ideologies was rather to secure the coherence and legitimization of the ruling class itself. For reaching that goal, no other classes were necessary to participate in these ideologies. Therefore, the ideology of the ruling class is not the dominant ideology.To avoid the conceptual ambiguity linked to the notion of dominant ideology, Wegener and Liebig[36] introduced alternative concepts of primary and secondary ideologies to social justice research. By primary ideology, they meant an ideology that is held by the majority of a society, ideally by all of its members, whereas secondary ideology is an ideology endorsed only by particular groups in a society—possibly simultaneously with primary ideologies. The advantage of this conceptualization is that the concept of justice ideologies is no longer bound to a ruling class that forces the dominated into believing existing distribution to be just. Instead, primary and secondary ideologies are simply distinguished in quantitative terms. The primary justice ideology, according to Wegener and Liebig, characterizes a whole society in a quantitative sense and serves as a mechanism to create an encompassing consensus in society and provide a basis for a society’s legitimization by exerting a normative influence on the beliefs that most, or even all, people have about how goods should be distributed. These justice beliefs, they argued, reflect the cultural values characterizing the society in which those beliefs are anchored, and therefore, can be reconstructed by going back to the cultural values that have developed in a society’s history.Whether we experience and see economic inequality through the ideological lenses of the dominant class or the cultural history of a society, what matters is that such justice values that people hold, namely what ought to be, influence the subjective elements of perceptions of inequality, namely what is. Verwiebe and Wegener[32] further articulated this premise by emphasizing a conceptually separated, but functionally connected, relationship between the two modes of justice judgments: order-related and result-related judgments. According to them, order-related judgments are about principles of justice and in particular the institutional frame for distribution processes in a society (e.g., preferences for market principles versus state regulated principles). Result-related judgments, on the other hand, focus on the consequences of distribution rules. It measures the extent to which a given distribution is considered as just and tolerable. Verwiebe and Wegener suggested, From an analytical point of view, these ideological preferences (i.e., order-related) and the (result-related) justice evaluations of the income distribution are independent of each other. They address different justice objects: distribution principles and distribution results. Cognitively inconsistent as we are as human beings, our ideological preferences need not be in line with and may even contradict our justice perceptions of results in concrete cases. It is nonetheless possible that order-related preferences may affect the evaluations of distribution results. The extent to which individuals perceive an actual income justice gap in their society, for instance, may well be contingent on their ideological preferences for distributing income and wealth. (P. 134) The key claim here is that our ideological preferences for certain distributive principles may become of enduring and central criteria in terms of which the fairness of distribution results is evaluated and affect, wittingly or unwittingly, our perceptions of inequality. Findings from previous research directly and indirectly hint at this possibility. Headey[30], for instance, compared actual incomes of selected occupations in Australia with both perceived incomes and incomes regarded as legitimate, and discovered that most respondents grossly misperceived the actual income distribution and erroneously equated perceived incomes with legitimate incomes. These results, Headey argued, are attributable to the popular egalitarian justice sentiments among the Australian public and people’s desire to avoid a sense of personal deprivation or social injustice. That is, not only did public support for much greater income equality than now facilitate a corresponding increase in the discrepancy between actual, on the one hand, and perceived and legitimate incomes, on the other hand, but also people’s desire to construct a picture of economic reality that enables them to feel reasonably satisfied with their own economic lot within the society motivated them to level off differences between perceived and legitimate incomes and to believe that there is virtually no difference between legitimate and actual incomes. Following the speculations above, Headey concluded It should not be assumed that public perceptions of the distribution of social goods are even remotely accurate, and a normative standard of equality appears systematically to distort perceptions of reality. What ought to be largely influences perceptions of what is, rather vice versa. Perceptions of justice determine perceptions of fact. (P. 593) Similarly, Austen[37] discussed cross-country variations in public attitudes toward earning inequality in reference to justice norms, and argued for the importance of prevailing norms of inequality in societies as an explanation for the variations demonstrated. According to her, differential material environments between countries rendered only a partial explanation, and other factors should be taken into account. She arguedDespite this, significant intra- and inter-country differences in attitudes to wage inequality exist that cannot be explained by the different economic circumstances of individuals or nations. It appears that some countries, such as the United States, have social “norms” that tolerate relatively high levels of inequality, while the citizens of other countries, such as Australia, generally share a belief that the wage structure should be more compressed. Thus, an important dynamic relationship appears to exist between levels of inequality and the normative structures that relate to them. (Pp. 441-442) In a country like the United States, despite the rapid increases in wage inequality in fact, people showed a greater range of tolerance to inequality than in other countries, and Austen attributed it to the community’s compliance with “market-based pressures,” namely, acceptance of the justice of inequality in the market. Indeed, copious opinion research in the United States[3-9, 38-42] has demonstrated robust tolerance to inequality among the American public, e.g., opposition to welfare programs and stigmatization of the poor for their poverty, and scholars ascribed such attitudes to Americans’ commitment to meritocratic justice ideologies; that is, prevailing meritocratic justice norms, or strong rejection of material egalitarianism, buttressed popular belief in the benefits of inequality, and rendered people tolerant of poverty and income inequality, and intolerant of welfare programs[3, 4].Therefore, the Korean public’s critical concerns about economic inequality are more likely to be contingent on Koreans’ commitment to egalitarian rather than meritocratic distributive justice ideologies. In the following, using data from the ISSP module on social inequality, I measure how popular distributive justice norms of Korea are compared to those of other OECD counterparts and examine how they relate to public perceptions of economic inequality (or in this case income inequality) across countries.

3. Data

- For empirical and comparative analyses, I use data from the 1999 ISSP module on social inequality. As a representative survey of population aged eighteen and older, the 1999 survey collected attitudinal data on various issues regarding economic inequality in twenty-seven countries between 1998 and 2000. From this survey, fifteen OECD countries—Australia, Austria, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Northern Ireland, Norway, Sweden, Great Britain, the United States, Portugal, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland—were selectively chosen based on their different orientations toward free market and capitalism. According to Esping-Anderson’s typology[43], Nordic countries such as Norway and Sweden are well known for their social democratic welfarism, which promotes the principle of universalism, granting access to benefits and services based on citizenship, and limit the reliance of family and market to provide a relatively high degree of autonomy against social inequality and commodification of social provisions. In contrast, liberal welfare states such as the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan, and increasingly the United Kingdom are based on the principles of market dominance and private provision, idealizing the freedom of market competition and minimizing the state intervention. As the ideals of liberalism incorporate the maximization of the free market and hold all individuals responsible for their own economic fates, a low level of decommodification and a high degree of social inequality prevail. Countries such as Germany, France, and Austria are considered conservative in that while market justice norms still remain at the center of social justice, people who are unable to succeed in the market competition due to no fault of their own are salvaged through governmental intervention in the name of communality unlike in the individualistic liberal welfare states. Portugal is categorized as a Southern European Welfare regime[44, 45]. But, as Ferreira[45] argued, its welfare policy is considered a failure, since both the public and policy makers lack strong commitment to equitable social justice. Finally, the two post-communist countries, Hungary and the Czech Republic, are undergoing confrontation between the old and new social orders. Under the new market economy, more people than ever are becoming marginalized due to the growing economic disparities in the society, and this renders people feel nostalgic for the culture of equality experienced under communism[27, 46].Unlike the data for the fifteen OECD countries, the data for Korea came from the partially replicated 1999 ISSP module on social inequality, which was fielded in Korea alone in 2003. It was not until 2003 that Korea acquired official membership in ISSP, and later the same year the Korean General Social Survey (KGSS) carried out the survey. Comparable to the original 1999 survey, survey in Korea was also administered to a nationally representative sample of respondents aged eighteen and older, using multi-stage stratified sampling. Thus, it is noted here that using the 1999 survey for analysis entails a temporal difference in the data collection periods between Korea and fifteen other OECD countries. This difference, however, does not necessarily risk the usefulness of the 1999 data for comparison. In fact, using data from the 1999 survey rather serves the said purpose of this research well, rendering ensuing analyses and findings more relevant and comparable to Korea. As well remembered, between 1998 and 2000, when the survey was fielded, the world economy plunged into unprecedented waves of financial and economic crises. Immediately following the Thai crisis, the shock spread uncontrollably to other economies in the region and beyond, pulling down many East Asian developing and even developed countries like Japan whose macroeconomic fundamentals had been considered strong. The continued deterioration in the East Asian economies, coupled with the Russian financial crisis, subsequently depressed many European and North American markets as well, escalating fear of serious damage to major financial markets. Given the socio-economic circumstances of the period that spans the 1999 survey, no data would provide a better comparative outlook than the 1999 survey on how people around the world, not just Koreans, in times of growing instability and the crisis of local and global economies, shaped their beliefs and norms regarding economic inequality.

4. Measures and Methods

4.1. Popular Justice Sentiments

- Given that justice is essentially a matter of establishing a fair equilibrium of distribution of desired goods and undesired ills between individuals, an important normative question of distributive justice arises when one tries to decide what the relevant characteristics of distribution should be. That is, by virtue of what attributes or characteristics is each person’s due to be decided? As much as controversy has abounded among the normative theorists of justice over the question, empirical studies of public opinion have demonstrated the diversity of lay beliefs about distributive norms as well. Such pluralistic beliefs about justice, as Miller[47] stressed, may occur as people invoke several criteria of distribution and reach an overall judgment by balancing these criteria against each other.While a varying number of general principles of distributive justice have been put forward in many theories of justice, the following three norms-equity (or desert), equality, and need—have been most widely recognized as the main principles of distributive justice, and lay beliefs about justice have been analyzed in light of them. First, the principle of equity, also known as the principle of desert or merit, assumes that the only fair way of allocating benefits and burdens between individuals is to ensure that each gets the share he deserves according to his desert, or contribution[48-52]. Those who contribute more should get proportionally more than those who contribute less. If the relative ratio of contribution to share is unequally maintained for the individuals involved in a given distribution, then justice is violated. In other words, unequal distribution per se is not unjust under the principle of equity; injustice, instead, occurs, when people who are not equal are assigned equal shares. By this logic, the principle of equity, or desert, reflects the meritocratic discourse of distributive justice.The basic contention of the meritocratic justice approach is that justice must be able to identify and connect reasons for differential treatment that results in inequality. That is, justice requires treating like persons alike, not all persons alike. The moral justification of differential, or unequal, treatment of individuals in the meritocratic justice discourse, however, does not result from the premise of the unequal worth of all human beings. On the contrary, the discourse assumes that each individual, as a responsible sentient creature, is equally worthy in his experience and action, and is equally entitled to pursue his own happiness. Thus, whatever choices each individual makes, as long as the choice is dictated by deliberate free will, it is just for individuals to assume a corresponding responsibility for their own conduct and to be treated accordingly.The principle of equality, just like the principle of equity, or desert, draws upon the same premise of the equal divine worthiness of each individual. Each person, as a responsible sentient creature, is equally worthy in his experience and action, and is equally entitled to pursue one’s own happiness. The two principles, however, stand apart, as the premise of equal worthiness in the egalitarian justice discourse extends beyond the moral worth of an individual; it further requires equality of outcomes regardless of relative distributions and inputs. Equal shares in the distribution of outcome are supported, because individual distinctions based on generalized, situationally irrelevant, and evaluative comparisons of people run a risk of leading to the total neglect of an individual or a group of people by denying an entitlement to be considered merely as men of equal moral worth, regardless of their conduct or choices. Accordingly, economic egalitarianism stresses the limitations on income and hierarchical differences with the purpose of keeping individual distinctions to a minimum. This is achieved either by raising a wage floor, which ensures that everyone receive a decent minimum, or by suppressing the ceiling so that no one exceeds the limit, or both. Finally, the principle of need constitutes another widely recognized distributive principle. According to Campbell [53], the language of need is distinguished from equity (or desert) and equality, in the sense that it is subject to a teleological interpretation; that is, pursuing need per se is not an ultimate end state of distribution, but a precondition for real human fulfillment. As Marx himself acknowledged, meeting basic needs is of great importance, not only because neglect of them generates great suffering, but also because the manner in which a society goes about satisfying the material needs of its members determines everything else. This is why, in the communitarian context, need as a principle of justice dictates that resources be directed toward eliminating human suffering. Only after the material deficiencies that cause suffering disappear can human beings reach their full potential, and live together in harmony as a creative social entity and pursue genuine happiness.In sum, some similarities and differences between the three principles are noteworthy. On the one hand, they are similar to the extent that they all draw upon the common moral axiom of equal worthiness of individuals, according to which each person, as a responsible sentient creature, is equally worthy in his experience and action, and is equally entitled to pursue his own happiness. They are different, on the other hand, to the extent that they disagree with the justification for differential treatment that results in inequality. The desert- or equity-based meritocratic justice discourse finds its ground for unequal treatment of individuals in the moral axiom of equal worthiness of individuals, in the sense that all individuals, since they are viewed as equally free-willed agents who can intentionally intervene in natural events through their own choice and intention, should be accountable for the consequences they have brought up. As a result, those who contribute more should get proportionately more than those who contribute less.Unlike this meritocratic justice discourse, both the equality- and need-based justice approaches refute the moral justification of treatment that results in inequality. Their aversion to distinctions between individuals turns a blind eye to generalized, situationally irrelevant, and evaluative comparisons of people, and thus finds economic fairness in a condition where more individuals, ideal-typically all individuals, have an equal claim, regardless of their relative inputs and contributions, to the social benefits that afford them real human fulfillment, not simply the mere satisfaction of instant desires.Therefore, along the continuum of justice ideologies, the principle of desert constitutes a meritocratic justice ideology on the one end, and the principles of equality and need, coupled together, constitute an egalitarian justice ideology on the other end. Drawing upon this conceptual typology, I measured popular sentiments toward distributive justice principles of Korea and other OECD countries, using the following five questions from the ISSP survey. 1. PERFORMANCE: In deciding how much people ought to earn, how important should (How well one does the job) be?2. EFFORT: In deciding how much people ought to earn, how important should (How hard one works at the job) be?3. FAMILY: In deciding how much people ought to earn, how important should (What is needed to support a family) be? 4. CHILDREN: In deciding how much people ought to earn, how important should (Whether the person has children to support) be?5. EQUALITY: It is the responsibility of the government to reduce the differences in income between people with high incomes and those with low incomes.The original five-point response scales forPERFORMANCE, EFFORT, FAMILY, and CHILDREN (1=essential, 2=very important, 3=fairly important, 4=not very important, and 5=not important at all) and for EQUALITY (1=strongly agree, 2=agree, 3=neither agree nor disagree, 4=disagree, and 5=strongly disagree) were reversed for analysis. In light of the foregoing discussion of normative justice ideologies, these five items capture the central aspect of justice norms that normative theorists have discussed. The first two items, PERFORMANCE and EFFORT, measure adherence to the desert-based meritocratic justice ideology according to which unequal treatment of people by virtue of the effort and contribution that each individual makes is just and beneficial to society. The second two items, FAMILY and CHILDREN, conversely, measure adherence to the need-based egalitarian justice ideology according to which meeting basic needs of human beings is a precondition for achieving the genuine happiness to which every individual has an equal claim. Thus, prioritizing the basic welfare of the family, as the two items indicate, amounts to accepting need-based justice ideology. Finally, the last item, EQUALITY, measures adherence to the equality-based egalitarian justice ideology since forced government interruption arbitrarily changes the initial equilibrium of distribution in the market by allowing the poor to get more and the wealthy to get less than they deserve.For analysis, a two-step factor analysis was applied, where a country specific analysis was followed by a pooled-country analysis. In my study, these two factor analyses serve a different purpose. With a country-specific factor analysis, I test the cross-national commonality of the latent factor structures that I outlined for the five distributive considerations above. To this end, a separate factor analysis is carried out in each country on the correlation matrix of the five variables with pair-wise deletion of missing cases and “no answer” and “cannot choose” responses. Next, principal component analysis and scree tests with percentage of variance explained by each factor are used to obtain and screen an initial estimate of the number of factors to rotate. For rotation, orthogonal varimax is used. If respondents in given countries share comparable justice perspectives and the resulting factor structure (supposedly three factors: equity, need, and equality) is sufficiently similar and interpretable across countries, it suggests that there are no country differences in public understanding of the three justice norms. In such cases, a pooled-country factor analysis follows. Unlike the country-specific analysis above, a pooled-country analysis combines all respondents together, treating them as one single large pool. The purpose of pooling all countries together is to construct the common starting point from which each respondent’s relative factor scores are computed. That is, in a country-pooled analysis, unlike in a country-specific analysis, the computation of factor scores is carried out on the single common factor loadings which are derived from all respondents involved. Therefore, the ensuing factor scores make a better indicator of the respondent’s relative spacing for inter-country comparisons. For analysis, the unequal number of respondents in each country is adjusted by applying weights so that the same number of respondents represents each country in the pooled data set. Once individual respondent’s factor scores are computed, they are aggregated at the country level by sorting and tallying them up according to each respondent’s nationality, and are averaged for each country. Using those averaged scores as an index, I determined which of the three distributive justice principles embodies a dominating justice norm in each nation.

4.2. Perceived and Actual Income Inequality

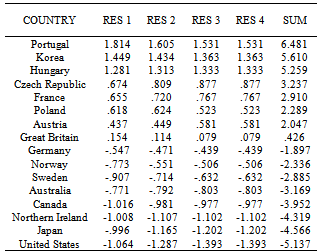

- The goal here is to measure the extent to which respondents in individual countries are over- or under-conscious of the issue of income inequality for the current level of income inequality in their society. To assess perceived income inequality across countries, the following question was employed from the survey.● Do you agree or disagree differences in income in (your country) are too large?Respondents specified their level of agreement to the statement, using a five-point scale—‘strongly agree,’ ‘agree,’ ‘neither disagree nor agree,’ ‘disagree,’ and ‘strongly disagree.’ Since varying public awareness of economic inequality across countries is of interest, I estimated the proportion of respondents who believed that differences in income in their nation were too large. To this end, percentages corresponding to the two positive responses, ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree,’ were summed for each nation.The following four income inequality measures were employed to estimate the actual level of income inequality in each country. ● The Gini index (GI)● Half the squared coefficient of variation (½SCV)● The mean log deviation (MLD)● The P90/P10 ratioAs Schwartz and Winship[54] and Allison[55] note, early empirical studies of inequality committed the methodological error of drawing upon a single index of inequality. This is problematic in that inequality is not necessarily a one dimensional concept; in order to encompass and measure its diverse aspects, they argue, different indices should be considered together. Given that different measures may yield different results and interpretations of income inequality, it is important to provide multiple, but more importantly, proper, measures of inequality. Schwartz and Winship[54] suggest three general criteria for selecting measures of inequality: principles of transfers, population symmetry, and scale invariance. The first criterion, also known as the Pigou-Dalton principle of transfer, is simply the idea that, if transferring money from the rich to the poor makes one distribution match another, the former distribution is less equal than the latter. The second criterion requires two distributions of unequal size to be made comparable by adjusting group sizes. That is, if two groups are of different sizes, comparison is made possible by weighting the populations. The final criterion requires measures to be robust in response to changes of measuring units. The currency used to measure income should not change the result. In addition, Allison[55] argues that measures of inequality should respond to relative, not absolute, differences among individuals, since, as Blau[56] notes, people are more sensitive to their relative position in the income distribution than to absolute differences in income level. Given the basic criteria, the following four indices—Gini index (GI), half the squared coefficient of variation (½SCV), the mean log deviation (MLD), and the P90/P10 ratio—are used in this study. These indices differ in their sensitivity to income differences in different parts of the distribution. For instance, the GI is sensitive to the middle of the distribution in that the change in the GI is a linear function of the number of people who are positioned between two points of the income distribution. Given that most individuals are located in the middle of the income distribution, the GI will give more weight to transfers among people in the middle of the distribution than transfers at either end of the distribution, i.e., the rich or the poor.Unlike the GI, the ½SCV and the MLD are members of the Generalized Entropy (GE) family of inequality indices. Depending on the level of α, the weight given to the difference between incomes at different parts of the income distribution, the GE shows varying degrees of sensitivity to income differences in the distribution; larger values of α correspond to greater sensitivity to income differences at the top. According to the recent work of Cowell and Flachaire[57], the GE measures with α > 1 are very sensitive to high incomes in the distribution, while the GE measures with α ≤ 0 are very sensitive to small incomes in the distribution. Thus, the ½SCV where α = 2 is very sensitive to the individuals with high incomes in the distribution, whereas the MLD where α = 0 is very sensitive to the individuals with low incomes in the distribution. Finally, the P90/P10 ratio is the ratio of the ninetieth income percentile to the tenth income percentile in the distribution. Unlike the first three measures above, this measure highlights the gulf in income between the top and bottom of the middle 80% of the distribution. It compares the income of an individual ‘near’ the top of the income distribution with the income of an individual ‘near’ the bottom. Thus, it does not capture the overall income inequality in the distribution, but provides a readily interpretable measure and an intuitive sense of polarization in the distribution. Due to the differing characteristics of inequality measures, as illustrated above, it is better to compare a set of measures than to use a single parameter, whether the scope of comparison is within a nation or between nations. Jarvis and Jenkins[58], for instance, used five indices of inequality that differ in their sensitivity to income in different parts of the distribution, including a high income-sensitive index (the ½SCV), middle income-sensitive indices (the GI and the Theil index), and low income-sensitive indices (the MLD and the variance of the logarithm), in order to capture the longitudinal impact of income mobility among the individuals (or groups) over time in Britain. Similarly, Goodman and Oldfield[59] used four measures—the GI, the P90/P10, income shares of different decile and percentile groups of the distribution, and the ½SCV—in order to detect changes in global inequality over time. Firebaugh[60], to challenge the polarization thesis of dependency theory, also used four indices—the GI, the Theil index, the SCV, and the variance of the logarithm—and showed that different interpretations of inter-country income inequality could be produced by the choice of index. Thus, employing multiple indices of income inequality is crucial to comparisons of inequality. The three measures of inequality discussed in this paper—the ½SCV, the GI, and the MLD—can provide a balanced view of income inequality because the indices represent “high income sensitivity”, “middle income sensitivity,” and “low income sensitivity,” respectively. In addition, the P90/P10 ratio serves as an alternative index of income disparity, particularly between the rich and the poor in society. A large disparity between the two groups suggests that the society is polarized.In order to investigate in comparative terms the extent to which the Korean public’s perceptions of income differences deviates from reality, I used Korea and fifteen other OECD countries as a unit of analysis, and the total percentages of the respondents perceiving income inequality as too large (as a dependent variable) were regressed on each of the four income inequality measures that the country has (as independent variables). The underlying assumption is that if perception exactly mirrors reality as it is, a country with a lower income inequality in reality should have a correspondingly smaller percentage of respondents perceiving income inequality as too large than a country with a higher income inequality in reality. If a country does not fall within this linear prediction and shows a certain degree of deviation, the country is a case where discrepancy between perceived and actual income inequality exists. To elaborate, if a country falls above the predicted linear line, more of the public in the country than expected actually view income inequality in their country as severe for the actual level of income inequality. Conversely, if a country falls below the predicted line, less of the public in the country than expected view income inequality in their country as severe. In other words, for its actual level of income inequality, less of the public than expected are conscious of its severity. Given the foregoing logic, I used the sum of the four sets of residuals obtained in each regression analysis as a measure of the discrepancy between perceived and actual income inequality of a given country.

5. Analyses and Findings

5.1. Popular Justice Sentiments: What Koreans Believe and how do They Compare?

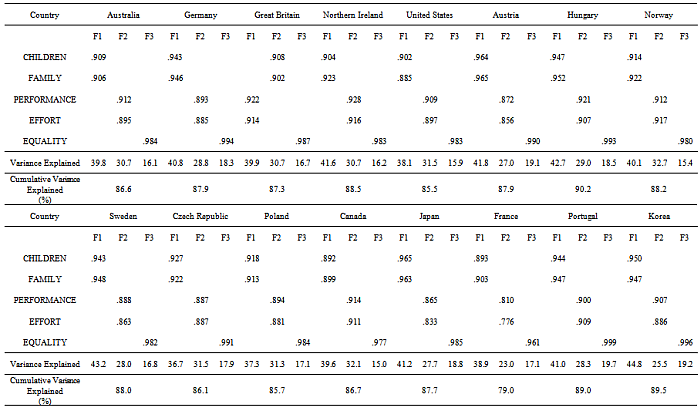

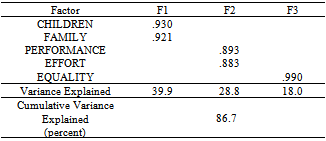

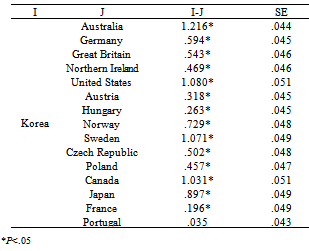

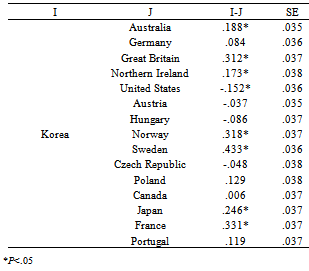

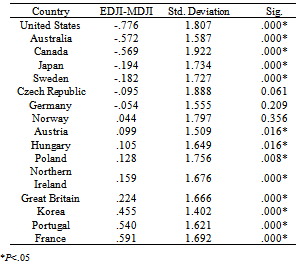

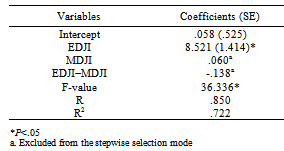

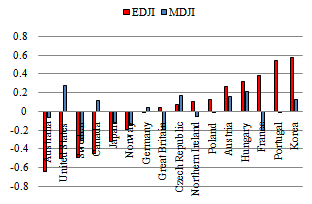

- Table 1 presents results from the country-specific factor analyses. As we can see, resulting pattern matrixes are almost identical across countries. Not only do three factors commonly account for between 85 and 90% of the variance in all countries but France, but also they are sufficiently similar and interpretable across countries to suggest that they tap the same underlying justice ideologies, where each of the three factors principally comprised items that represent the principles of need, equality, and desert, respectively.The presence of a common factor matrix across countries, therefore, warrants a pooled-country factor analysis. With the same screening and rotating procedures used in the country-specific analysis, the pooled-country analysis also results in a three factor solution. According to Table 2, not only do three factors account for 86.7% of the variance, but also, after rotation, each factor exclusively loads on variables representing different principles of distribution. F1, for instance, comprises variables that justify the principle of need, FAMILY and CHILDREN, F2 comprises variables that justify the principle of desert, PERFORMANCE and EFFORT, and F3 comprises EQUALITY.Given pattern matrix in Table 2, the factor scores on the principles of need and equality (F1 and F2) were combined to measure the strength of popular sentiments toward egalitarian distributive justice ideology (EDJI), on the one hand, and the factor score on the principle of desert (F3) was used to measure the strength of popular sentiments toward meritocratic distributive justice ideology (MDJI), on the other hand. Results are quite telling. As compared in Figure 4, Korea marks the highest EDJI score of .581 of all, indicating that Koreans, compared to any of their OECD counterparts, retain the strongest egalitarian justice sentiments. Similarly, the Portuguese also retain as strong egalitarian justice sentiments as Koreans. Though not as conspicuous as these two, the mass publics in France, Hungary, and Austria also possess a relatively high level of egalitarian justice sentiments. Australia and the United States, in contrast, mark the two lowest EDJI scores of -.635 and -.499, respectively, indicating that the mass publics of these two countries retain the weakest egalitarian justice sentiments of all.

|

|

| Figure 4. Mean Factor Scores on Meritocratic and Egalitarian Distributive Justice Ideologies |

|

|

|

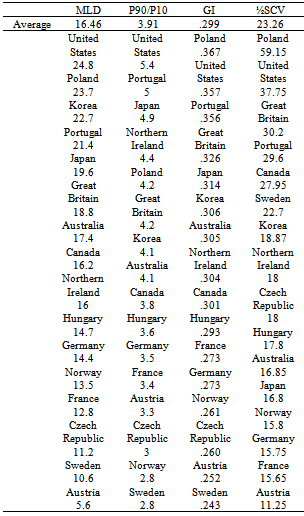

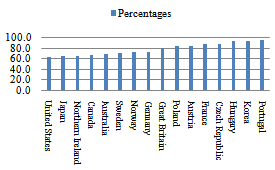

5.2. Distributive Justice Ideologies and Perceived Income Inequality: What do Koreans See and why?

- Having identified the nature of the primary and secondary justice ideologies of Korea and other OECD countries, I examine the effect that the prevailing justice ideology in a society has on people’s perceptions of existing inequality. How do justice ideologies interact functionally with our judgments of inequality in reality?Measured by the P90/P10 ratio, the United States again marks the highest level of inequality amongst all. The ninetieth percentile household earns more than five times as much as the tenth percentile household. Similarly, in both Portugal and Japan, the ninetieth percentile household earns five times as much as the tenth percentile household. In contrast, the two Nordic countries, Norway and Sweden, mark the smallest ratio of 2.8, indicating a very low level of income polarization between the top and the bottom of the distribution. In case of Korea, its relative stance does not appear as bad as it did with the MLD. The ninetieth percentile household earns four times as much as the tenth percentile household, and this gap is seventh largest from the top, putting Korea at the medium position.

|

|

| Figure 5. Percentages of Respondents Perceiving Income Difference as Too Large |

|

|

6. Conclusions

- In this paper, I have investigated empirically and comparatively how the Korean public’s justice sentiments and perceptions of income inequality compare to other OECD counterparts’ by using data from the 1999 ISSP module on social inequality. My analyses revealed that Koreans, compared to other OECD publics, not only placed a much stronger egalitarian strain in their scheme of distributive justice, but also were largely concerned about the presence of large income differences in the society, the fear of which in fact was unduly overstated for Korea’s relatively equitable income distribution. Based on the ideology thesis, I further investigated the hypothesized mediating effect of popular justice sentiments on public perceptions of income inequality, and found that not only did egalitarian justice ideology, as opposed to meritocratic justice ideology, facilitate public misperceptions of large income inequality across countries, but also this mechanism fit better to Korea than to others.Considering the dire economic circumstances of the period during which this survey was fielded across countries, namely transmission of Asian financial crisis into global economic crisis, increased perceptions of risk and negative prospects for growth must have been a common social milieu around the world, not just in Korea. Nonetheless, as manifested through my analyses, the Korean public’s general economic attitudes were much more radical and critical than others’ to the extent that not only did Koreans place much stronger egalitarian strains in their pursuit of distributive justice, but also the majority of Koreans believed in the crisis of large income inequality, the perceived threat of which was in fact considerably overstated for what it really was. Due to the temporal limitation of the data, this research cannot evidence, or claim, whether and, if so, to what extent the said radical and critical aspects of Korean beliefs about and norms of income inequality are generalizable to different time periods. That is, with findings from this research alone, it is hard to conclude for sure what constitutes the fundamental nature of Korean beliefs about and norms of inequality. Therefore, it is acknowledged that future research needs to address this problem in more detail by using additional data collected at different times, ideally before and after the year 1999. This comparison will allow us to track changes over years, if any, in public norms of and beliefs about inequality of Korea and identify the core Korean beliefs about and norms of inequality. Even in the absence of such comparable datasets, nonetheless, it is still worth noting that the radical and critical aspects of Korean beliefs about and norms of income inequality that my research disclosed approximate very closely to what Western scholars described earlier about Korean society during the 1980s, namely, pervading public anxiety over and critics of economic inequality and social hostility toward the wealthy. Recalling that the overall economic circumstances of Korea during the 1980s, as I discussed earlier, were not as dire as they were in the aftermath of Asian financial crisis, this considerable overlap of public attitudes toward inequality between the two time periods hints at the possibility that the radical and critical nature of Korean views of inequality, in both descriptive and normative aspects, may well be a habitual practice, namely social habitus. In that economic inequality is an inevitable feature of the socio-economic structure of capitalist societies, the success of stable capitalist development, as Lane and many other students of social justice study have articulated, depends in large part on people’s ability and willingness to adapt to the cyclical nature of free market system. That is, the extent to which people can perceive and legitimize persistent inequality in the society in the context of social justice and these favorable perceptions and norms subsequently can keep in check radical struggles against inequality becomes a critical requisite for the development of stable capitalism. In this regard, the Korean public’s unfavorable perceptions and norms of economic inequality, as diagnosed in this paper, appear to cast a bleak, if not worrying, outlook on the development of harmonious capitalism in Korea. As long as Koreans place a strong egalitarian strain on their schemes of distributive justice and as a result are provoked to see more inequalities than are there, Korean society would become more vulnerable to the outbreak of unnecessary social conflicts over the issue of inequality.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML