-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Sociology

p-ISSN: 2169-9704 e-ISSN: 2169-9739

2013; 3(2): 28-36

doi:10.5923/j.ijas.20130302.03

Between two Worlds: Representations of the Rural and the Urban in two Portuguese Municipalities

Maria Manuela Mendes 1, Renato Miguel do Carmo 2

1CIAUD, Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Portugal

2Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Centro de Investigação e Estudos de Sociologia (CIES-IUL), Lisboa, Portugal

Correspondence to: Maria Manuela Mendes , CIAUD, Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Portugal.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

In a context of contemporaneousness in which there is little mention of the articulation between urban spaces and those with predominantly “rural” characteristics, we seek to make a contribution towards the “social construction of the rural space” and towards an understanding of the relation spheres and articulation between these spaces and the dynamics of urbanisation. This analysis was conducted within the context of a larger study that used several tools for gathering information (analysis of secondary data, questionnaires and interviews) in seeking to understand the principle recent transformations in the more peripheral and rural areas of the Algarve region. The Algarve is better known, both nationally and internationally, as an attractive tourist destination for those seeking sun and accessible beaches; however, it is also a very diverse region (with mountainous and rural landscapes), and one, moreover, little studied by the social sciences. Here we discuss and problematize social representations of the local space by the residents of two municipalities: São Brás de Alportel and Alcoutim. Based on the results of a study concluded in 2010, we discuss the responses to a survey of 678 residents in both municipalities (the questionnaire was given to a representative sample of residents according to gender and age [2001 Census]), in order to understand their views on the development of their municipality, about the area’s strong and weak points and about the main changes taking place in respect of the (re)composition of the local population. These two municipalities, which are very different despite their geographical proximity, were selected in order to allow an analysis of long-term structural changes; however, here we are particularly interested in discussing some of the exploratory analysis indicators associated with the respondents’ subjective perceptions. The representations by residents of both municipalities are various and contrasting, with asymmetries and diversities between them. This analysis leads us to a conclusion in respect of the limits on the use of conceptions that are naturalist, a priori and which are based on the reification of the spatial characteristics and social practices of social protagonists within rural spaces. It is necessary to devise alternative conceptual tools, ones that take into consideration the relational spaces promoting the dynamics of inter-relationship, diversity and of hybridism that must be incorporated into socio-territorial and multi-scale projects and policies (local base, connected to the national and the international).

Keywords: Rural, Urban, Social Representations, Algarve, Portugal

Cite this paper: Maria Manuela Mendes , Renato Miguel do Carmo , Between two Worlds: Representations of the Rural and the Urban in two Portuguese Municipalities, International Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 28-36. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20130302.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- We believe contemporary sociological studies in Portugal have not paid enough attention to the links between urban spaces and those spaces in which ‘rural’ characteristics tend to dominate [1]. It is our aim, therefore, to contribute towards a broader debate on the “social construction of the rural space” and to seek to understand the relation spheres and exchanges between these spaces and the process of urbanisation. In particular, we will discuss and problematize the social representations of the local space by the residents of two municipalities in Portugal’s Algarve region: São Brás de Alportel and Alcoutim. “Rural” areas have normally been represented as being peripheral and marginal; however, our goal is to reflect on the capacity for autonomy within these spaces and make a contribution towards obtaining an understanding of the relational spheres and the links between these spaces and the dynamics of urbanisation. We ask: are we looking at a space that is perceived as being marginal and remote –“the deepest countryside” far from the major city?In fact, these municipalities are located in the interior of the Algarve, an area that has experienced a differentiated process of socio-spatial change. While located in the interior, São Brás de Alportel is close to Faro, the largest city in the region, and during the past two decades its population has grown, with the town exhibiting important dynamics of urbanisation. Alcoutim, on the other hand, is experiencing depopulation and the consequent ageing of its residual population.Based on a study that took place from 2008–2010, we will examine the results of a questionnaire completed by 678 residents from both municipalities. We intend to identify and understand the opinions of those surveyed in respect of the extent of their respective municipality’s development, their views on its strongest and weakest points and, finally, on the main changes that the (re)composition of the population.For this reason, it is necessary to analyse “collective representations” in the sense used by Durkheim, since as soon as they are constituted they become partially autonomous realities [2], thereby leading to a more profound understanding of the representations of the inhabitants of the two municipalities in respect of their space.1According to Jodelet [3], to represent or to be represented constitutes an act of thought through which an individual is related to and interacts with an object. Social representations are formed both through and within the field of “communication relations” and are simultaneously the result and a process of them ental activity through which individuals and groups reconstitute the real with a specific significance (symbolic dimension). These processes, resulting from a social and psychic dynamic, intervene in their configuration. They stand as a means for the social reconstruction of reality, and construct themselves in the “conflicting and constituent” web of social interaction [4].This level of analysis allows us a brief incursion into the symbolic domain, through the analysis of the meanings actors confer upon their practices [5]. Since it presupposes certain knowledge in order to deal with collected information, every representation is cognitive; however, this act of knowledge is activated through a specific practice and is influenced by society’s adopted discourse.The social representations constitute a form of knowledge that permits the comprehension, evaluation and explanation of reality [6].2 One of the main functions of social representation is to familiarise individuals with that which is strange to them: they are based on cultural categories that allow us the classification and description of people, situations and objects to compare, explain and objectify behaviour.On studying social representations we wish to understand the way in which individuals understand the world in an effort to grasp it and to solve their (existential, emotional and relational) problems. We study human beings that think, devise questions and seek answers, and which are therefore able to state how individuals and groups move in the context of a thinking society, which they themselves produce through the communication they establish [7]. For Oliveira and Amaral [7], the theory of social representation spreads, adjusts and opens itself to several traditions, stimulating and generating a number of areas ripe for investigation, but without favouring any methodology or research method while also offering the researcher the choice of what is most appropriate to their work. Therefore, “we should examine and grasp certain opportunities that the study of social representations offers” [8]. In short, social representations are performed, shared and define a certain social situation, working as a cognitive “map” that makes social reality understandable, thus ordering social relations and the behaviour of each individual towards others [8]. According to Lefebvre [9] each individual is endowed with a space competence and a performance that determines their specific social practice. Nevertheless, representations of (conceived) space are related to the production of relations and the “order” they impose. Designing the space means to represent it from a given system of signs (constructed by planners and technocrats). However, “spaces of representation” are associated with daily experience, including clandestine and underground aspects of social life (experienced by residents, users, artists and intellectuals’). The relationships between “social practices”, “representations of space” and “spaces of representation” are not linear and simplistic rather, they are fraught with tensions and struggles.The production of space must be analysed as a dynamic and dialectic process. According to Lefebvre [9], space should not be interpreted as a mere receptacle of social relationships; rather, it is produced daily and is grounded indifferent practices and social representations [10]. In this sense, we conceive rural space not as a stagnant or isolated place suffering from demographic problems, but as inter connected realities that combine different and contradictory processes [11].The views of the residents of São Brás de Alportel and Alcoutim are here understood as reference points from which individuals communicate with each another: which both places their world and places them within it. The content of these representations rests on three analytic axes: the weak and strong points of the local territory, the customs and functions of the space and the main changes that occur in the (re)composition of local populations.

2. Local Contexts: Diversities and Singularities

- The Algarve region illustrates the population tendencies that can be generalized for the whole country: “littoralisation” (internal migration to coastal areas), bipolarisation and desertification (the abandonment of population centres away from the coast). As a consequence of urbanisation and the population increase in the coastal regions, there has been a decline in the population of non-coastal (interior) Algarve. Moreover, with the (also natural) processes of desertification, the socio-demographic composition of the Algarve has become increasingly differentiated, with the two urban centres of Faro (in the middle coastal area) and Portimão (in the west) constituting two poles in the region’s urban system.The municipalities of São Brás de Alportel and Alcoutim, which are both in the interior, are quite different. The former was integrated in the urbanisation dynamic of the region that is directly linked with the district capital (Faro). By contrast, Alcoutim’s marginalisation has been accentuated through its relationship with less important urban centres, such as Vila Real de Santo António (a municipality located on the border with Spain), and which has a particularly difficult linkage due to its peripheral character, which is accentuated by its relative inaccessibility. São Brás de Alportel has been experiencing population growth since 1991, while Alcoutim’s population has been in decline. Between 2001 and 2008 the population in Alcoutim fell by17.7 per cent, while that of São Brás rose by 25.3 per cent. In 2008 the population of Algarve was 430,084; in Alcoutim it was 3, 104 and in São Brás de Alportel it was 12,569 [1].

3. Potential and Vulnerability of the Municipalities

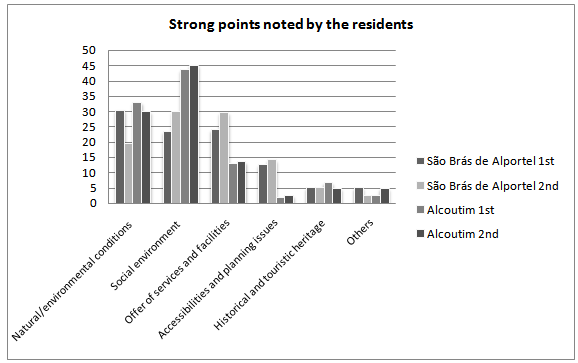

- Research carried out in the Nordic countries shows that despite the change dynamics in the representation of rural areas, they are marked by a certain nostalgia that is attached to the past and which is indicative of rural idealisation. Anglo-Saxon literature has also contributed to the diffusion of a mythical, positive and even romantic image of country life [12] [13]. In Portugal it is also possible to uncover a certain “discourse about the landscape brought from the past”, which is marked by a clear tendency to a certain nostalgic settlement [14]. Looking at the strong points of both municipalities, we can see that issues related to the (natural) landscape and social environment occupy a special position in the inhabitants’ view of São Brás de Alportel and Alcoutim, constituting themselves as potentials mobilisers for their strategic development. The idyllic and natural landscape also works as important elements in the discourse and representation of space. The reserve function of the physical space [15] is still one valued by residents in both communities.Taking into account the profile of the responses, in São Brás de Alportel the most frequently mentioned strong points were the territory’s natural environment and the social, cultural and sport facilities available (Fig. 1). We note slight differences in the views expressed by men and by women. Women tend to value the facilities and services on offer (29.9 per cent) and the natural and environmental conditions (28.2 per cent), while men value environmental factors (32.3 per cent) and the social environment (24.2 per cent). For those with more educational qualifications, the landscape is of secondary importance to the social environment (41.1 per cent).

| Figure 1. Strong points noted by residents Source: CIES 2009 |

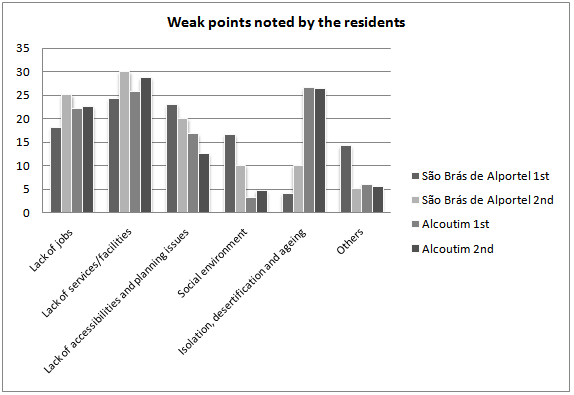

| Figure 2. Weak points noted by residents Source: CIES 2009 |

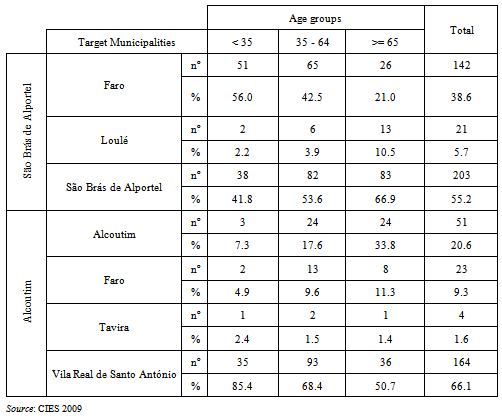

4. Work and Consumer Spaces

- Even if we acknowledge there is a socio-economic model in which the economic domination of the cities persists, the social division of work between the city and country and the favouring of urban lifestyle [17][18][16] does not prevent us from observing diffuse or even emergent ways of life in the municipalities being studied. It is possible to observe diverse and contrasting practices, as well as spheres of tension and inertia between the traditional and the contemporary. The rural spaces are generally seen as spaces of production, disregarding their value as spaces of consumption that have other uses, functions and innovative activities associated with tourism, recreation, leisure and asceticism [19][13]. The question of mobility, since the binomial production and consumption are factors of spatial mobility, is implicit in this analysis [11]. “Spatial mobility is understood as competence, which refers to the ability to project beyond, not only in terms of performance but also in terms of [daily] practice” [20].The existence or non-existence of the accumulation and inter-penetration of economic activities may suggest the existence or non-existence of an economic dynamism with a certain density and diversity that is constructed (or not) on the interaction between different economic agents. Looking at the functions associated with the importance of the local labour and consumer markets, we see that in São Brás de Alportel the majority of respondents believe residents work outside the municipality. The residents’ labour markets, as well as their investments, are possibly situated outside the municipality, establishing their dependence on surrounding municipalities; thus we are able to perceive the imbalances and socio-territorial cleavages within the region being studied.As we have already seen in Alcoutim, only those who are successful in finding employment remain there, thus for 72.5 per cent of respondents, residents work within the municipality which possesses a degree of autarchy in relation toits job market: one that is apparently less dependent on the surrounding communities. In São Brás de Alportel there is a closer relationship with its neighbours, particularly in relation to Faro (69.1 per cent). These representations seem to correspond to the practices identified in each municipality. In Alcoutim, the youngest note that their municipality polarizes job offers, while in São Brás de Alportel the municipality of Faro has a broader consensus, particularly among respondents aged 35–64.Nevertheless, São Brás de Alportel appears to be an attractive place for consumers, since 55.2 per cent of its population admits to shopping there (Table 1) although Faro continues to have a centripetal influence for 38.6 per cent of respondents. While 55.2 per cent of residents prefer to shop in São Brás de Alportel, among the older age group this figure rises to 66.9 per cent). The importance of Faro to the residents of São Brás is clearer among those with secondary and higher education (50.5 per cent). It is also possible to find differentiated opinions by gender: women are divided between São Brás (48.7 per cent) and Faro (47.1 per cent), while men clearly prefer São Brás. In Alcoutim it the supremacy of the municipality is also evident among those with the less formal education (31.3 per cent) and males (29.3, compared to 12.9 per cent of women). It will be interesting to consider the variations in terms of gender, since it was a less significant variation when we questioned people about their mobility practices.

|

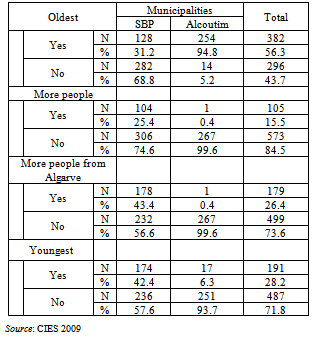

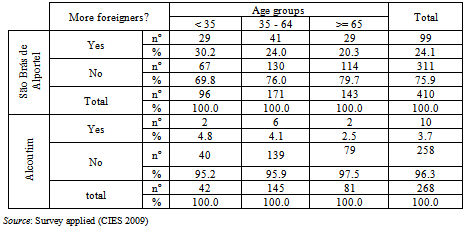

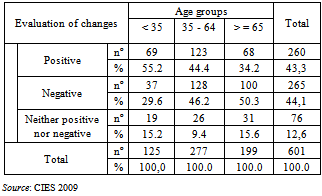

5. Changes in the Composition of the Resident Population

- We were also interested in understanding whether the responses allow us to foresee elements of change in the municipalities’ socio-demographic composition (Table 2.).It is possible to observe a dichotomy between both municipalities. In Alcoutim we see the population has aged (94.8 per cent), while São Brás is currently experiencing demographic rejuvenation (68.8 per cent). This tendency is more evident among the younger age group (77.1 per cent), since those in the oldest group believe the population has aged (44.8 per cent). We also note some convergence of opinion in respect of the fact the number of people living in the municipality has not risen, which is particularly true of Alcoutim (99.6 per cent). In terms of demography, São Brás de Alportel has become home to more national migrants, mainly “more people from the Algarve” (42.4 per cent) and “younger people” (43.4 per cent), thus fuelling the processes of demographic rejuvenation. This town also seems to have become a nesting place for the processes of reconfiguration resulting from migratory movements and the socio-demographic dynamic. In Alcoutim, the weakness of demographic dynamics is reflected in the respondents’ view that the town’s population has aged, and that is has neither increased in size nor incorporated migrants from surrounding spaces.

|

|

|

6. Concluding Remarks

- The results derived from the survey of the residents of São Brás de Alportel and Alcoutim demonstrate that there is vast diversity in rural Algarve.The opinions of these two communities are characterized above all by heterogeneity, diversity and disparity, which simultaneously reveals social and spatial continuities.The contents of the residents’ responses are diverse and contrasting, with asymmetries and variations between the two municipalities. It seems the question of what is the social and symbolic significance of the rural seems to be an excellent opportunity for clarifying concepts and refining the scientific analysis of several constructions around the social and ideological dimensions of the phenomenon [22].Alcoutim emerges as a space of constraints: it seems peripheral and even paradoxical, since its apparent autarchy in respect the labour market is largely a sign of the town’s isolation, desertification and ageing population. In this sense, taken as a space of immobility and of the inability to change, it is perceived negatively (it neither grows nor incorporates new inhabitants). Its main potential lies in the social environment, specificallyonitstranquillity/calmness/ quietness, followed by its natural/environmental conditions.São Brás de Alportel is presented as an interstitial, permeable and hete rogeneous spacefull of discontinuities and marked by some dynamic, since it produces and incorporates change processes and is capable of renovation (a rejuvenated population consisting of Portuguese and foreign immigrants). However, it still depends on Faro for its labour market. Faro continues to proclaim itself as the regional capital of the Algarve and its central polarizing location [23]. São Brás de Alportel has transformed its social fabric through the arrival of new residents and the settling of a more diverse population. Moreover, it is able to attract consumerism consumers and the changes are perceived as positive. This municipality combines potential and vulnerability: the natural/environmental conditions and the social, cultural and sports facilities are combined with a shortage of medical facilities and services and a lack of accessibility, transport and of an urban infrastructure. It is important to look beyond the dualisms and rural-urban dichotomies that seek to explain how urban-rural interactions create geographies of disparity and opportunities [24], and to resist essentialist and reification theses, thus contributing to the creation of categories of analysis and discourse that are of a relational nature and that pay attention to more than just the spatial and social continuities. These concepts and terms will continue to have pragmatic value in the identification of a general category of circumstances for study and, in the absence of alternative datasets, will continue to have the ability to characterise descriptively different types of locality. However, they are a potentially insufficient and misleading guide to local policies [25] that should be territorially based.

Notes

- 1. A Project funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology/ (PTDC/SDE69882/2006). Research Team: Renato Carmo (PI) Daniel Melo, Manuela Mendes, Sofia Santos – CIES-IUL, Lisbon University Institute2. This concept has at its genesis the notion of “collective representations”, as described by Émile Durkheim, when he wrote “‘une fois constituées, deviennent des réalités partiellement autonomes’, agissant par l’action d’explication, de formulation et d’information (au double sens de façonnement et de diffusion), inhérente à toute forme de représentatiton.”, in P. Champagne et al. [2].

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML