-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Sociology

p-ISSN: 2169-9704 e-ISSN: 2169-9739

2013; 3(2): 19-27

doi:10.5923/j.ijas.20130302.02

Consumers, Waste and the ‘Throwaway Society’ Thesis: Some Observations on the Evidence

Martin O’Brien

School of Education and Social Science, University of Central LancashirePreston PR1 2HE,UK

Correspondence to: Martin O’Brien, School of Education and Social Science, University of Central LancashirePreston PR1 2HE,UK.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The ‘throwaway society’ thesis – invariably attributed to Vance Packard (1967) – is widespread in social commentary on post-war social change.It represents, simultaneously, a sociological analysis and a moral critique of recent social development. In this article I take a brief look at the core of the ‘throwaway society’ thesis and make some comment on its modern origins before presenting and discussing data on household waste in Britain across the twentieth century.I conclude that there is nothing peculiarly post-war about dumping huge quantities of unwanted stuff and then lambasting the waste that it represents.When the historical evidence on household waste disposal is investigated, together with the historical social commentary on household wastefulness, it appears that the ‘throwaway society’ is a great deal older than Packard’s analysis has been taken to suggest.

Keywords: Consumerism, Waste, Crisis, Throwaway Society, History

Cite this paper: Martin O’Brien, Consumers, Waste and the ‘Throwaway Society’ Thesis: Some Observations on the Evidence, International Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 19-27. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20130302.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- It is commonly asserted, in developed countries, at least, that there is a crisis of waste and a failure of waste management policy.Moreover, the crisis is said to arise from the fact that contemporary consumer societies have developed a ‘disposable’ mentality in a ‘throwaway’ culture, and now discard items that, once, would have been reused, recycled or held in stewardship by our ancestral bricoleurs.These claims are so commonplace, so much a part of the commonsense of public and private life, that few have examined whether or not they are true and, with some exceptions (see Rathje& Murphy, 1991, for a rare discussion)[14], little evidence has been provided to establish their veracity[12].In fact, these claims, for the United Kingdom at least, have less evidential foundation than might be expected.They have the effect of misrepresenting what is happening in relation to waste in the contemporary world and they also gloss the past.In the simplest terms, it is not proven that contemporary consumers waste more than their historically miserly counterparts.Nor is it true that, in the past, our grandparents and their grandparents ‘stewarded’ objects and reused, recovered or recycled significantly more than happens today.Instead, the available evidence appears to show that contemporary consumers waste little more than their historical counterparts.This fact goes against the grain of both public and expert opinion but there are two sets of questions that can help to clarify why the consumerism equals waste crisis argument stands in need of a critical assessment.First, there is an important conceptual difference between talking about what people throw away and talking about what people waste.If one society deposits more unused materials on the environment than another one, does this mean it is more wasteful?Or does it mean that it processes more in the first place – so that there is simply a greater quantity of materials passing through its various industrial and domestic sectors?Is paper or plastic in a landfill more wasteful than offal or ash on the street, for example?It is far from clear that, as a proportion of what is produced and consumed, present-day consumers squander any more than any historical society has ever done.This is not to say that larger and/or more toxic depositions have no greater environmental impact but that is a rather different proposition to the claim that contemporary consumers are inherently more profligate.Second, by and large, the claim that contemporary societies are unusually wasteful compared to the past is based on an analysis only of municipal wastes and their relation to consumer discards.The time-frame for the analysis has tended to be short – where any time-frame is referenced at all less than a decade is typical.However, looking at patterns of twentieth century household waste suggest that today’s consumers are not necessarily as profligate in relation to the past as contemporary commentary tends to imply.In this article I take a brief look at the core of the ‘throwaway society’ thesis and make some comment on its modern origins before presenting and discussing data on household waste across the twentieth century. I conclude that there is nothing peculiarly post-war about dumping huge quantities of unwanted stuff and then lambasting the waste that it represents.

2. ‘The Great Curse of Gluttony’

- An important part of the problem with the throwaway society thesis is that it is rooted in a family of ideas about the ‘crisis of waste’ that brings together a moral critique and a sociological analysis of consumerism.The moral critique pays attention to escalating demand, high product turnover, and built-in obsolescence in a society increasingly oriented towards convenience.The sociological analysis pays attention to economic and cultural changes (particularly in the post-war period) relating to levels of affluence, patterns of taste and industrial innovation.Thus, Matthew Gandy (1993: 31) claimed that:‘The post-war period has seen a dramatic increase in the production of waste, reflecting unprecedented global levels of economic activity.The increase in the waste stream can be attributed to a number of factors: rising levels of affluence; cheaper consumer products; the advent of built-in obsolescence and shorter product life-cycles; the proliferation of packaging; changing patterns of taste and consumption; and the demand for convenience products.’Hans Tammemagi (1999: 25-6) picked up on this worldview and blamed post-war ‘consumerism’ for the waste crisis in almost exactly the same terms.However, the critique of wastefulness always exceeds a sociological analysis of waste as such and invariably revolves around a moral critique of the consumer society.Thus, Zygmunt Bauman’s analysis of the contemporary culture of waste descends rapidly upon modern society’s ‘addiction’ to consumption and disposal[1] to argue that said culture has become ‘a culture of disengagement, discontinuity and forgetting’[2]. John Scanlan charged his voraciously wasteful fellow citizens with absent-minded, blind ignorance[16]. Jeff Ferrell, meanwhile, accused his consumption-driven American compatriots of promoting an ‘existential affirmation of domination and control’ (2006: 192). The ‘culture and economy of consumption,’ writes Ferrell, ‘promotes not only endless acquisition, but the steady disposal of yesterday’s purchases by consumers who, awash in their own impatient insatiability, must make room for tomorrow’s next round of consumption’ (ibid: 28).In all of these cases, the critique is directed at post-war social development and implies that there is something peculiarly wasteful about contemporary society; that modern consumers are uniquely profligate, ignorant, disdainful of their consumption behaviour compared to their parents and grandparents.Moreover, the disdain is a feature not only of their specific acts of wasting but has seeped out to become a cultural force in its own right: the callous wastrels of contemporary consumerism have built, so to speak, the callous culture they deserve.However, there remain some basic questions about whether or not the evidence underlying the moral-sociological analysis is sufficient to support the conclusions.Is it true that post-war consumers are in fact uniquely wasteful?Is it true that unproblematic moral lessons can be drawn from the past: that our forebears were more careful or less wasteful; that they held objects in stewardship whilst we disdainfully discard them?The questions are particularly pertinent because the critics do not take history seriously: in none of the cases that I have cited is there one iota of serious reflection – let alone empirical evidence – on the history of wasting.Yet without evidence how can any scholar bring themselves to level such a deeply insulting range of accusations against their fellow citizens?The fact is that the critique of consumer decadence precedes World War Two by several decades (at least).Frederick Talbot (1919, and below), for example, castigated the wastrels of the early twentieth century for their callous destruction and disposal of the valuable contents of their dustbins and his was not an isolated voice (see[19]; Koller,[10] – whose book was published originally in 1902 in Germany).It is certainly true that the terms through which the critique was levelled were different to the terms now commonly used.Yet this difference is itself a matter of historical and sociological interest: the modern critique of wasteful consumers did not drop, unbidden, out of the sky.It does not reflect something obviously true about present day consumers.Instead, it represents a particular outlook on the relationship between waste and society: one not shared exactly by our forebears and one unlikely to be shared by succeeding generations.Whilst contemporary critics of consumer profligacy (especially those of a leftist persuasion) tend to cite Vance Packard (1968) with approval[8] they invariably omit to mention that Packard’s assessment of the throwaway society was rooted in an immensely conservative and thoroughly right-wing source.The modern moral critique of consumerism and its association with gluttony and pointless ‘waste’ – and all of the associated insulting epithets heaped on contemporary consumers – was actually born in the midst of World War Two and not in a succeeding age of moral decline.‘For it is the great curse of gluttony,’ wrote Dorothy Sayers in her 1941 essay ‘The Other Six Deadly Sins’, ‘that it ends by destroying all sense of the precious, the unique, the irreplaceable’[15]. Modern over-production and over-consumption, she claimed, was intent on generating waste, on destroying all true values and substituting the pointless, and unsustainable, desire to possess and revel in ‘all the slop and swill that pour down the sewers over which the palace of Gluttony is built’ (ibid).The essay is part of a theologically inspired collection published as Creed or Chaos? (1948). The collection consists of a series of laments on the moral decay of mid-twentieth century society, where no-one has the right attitude to each other, to the community at large, to work, to religion, or anything else.They comprise an intemperate tirade against Keynesian demand management and, in Sayers’ opinion, the excesses of the burgeoning welfare state.Rooted in Western Christian dogma, the essays condemn almost the entirety of social and industrial development since some (unspecified) mythical age of craft, community and thrift.For Sayers, the modern industrial world is a world of artifice and pretence whose earthly span must surely be near its end, as she suggests in the 1942 essay ‘Why Work?’:‘A society in which consumption has to be artificially stimulated in order to keep production going is a society founded on trash and waste, and such a society is a house built on sand’ (1948: 47)This polemical blast against the entire edifice of Keynesian economics appears as the frontispiece of Vance Packard’s celebrated text The Waste Makers (first published in 1960).Given the widespread popularity of the vulgar version of Packard’s thesis – that manipulative advertising and marketing strategies are tools for the expansion of an unsustainable consumption-led economic system – it is more than surprising that its right-wing, dogmatic, theological roots are not the subject of more sustained, reflective commentary.That there are more connections between Packard’s thesis and Sayers’ tirade beyond the frontispiece is evident on even a cursory comparison between the books.For example, ‘We need not remind ourselves of the furious barrage of advertisements by which people are flattered and frightened out of a reasonable contentment into a greedy hankering after goods which they do not need; nor point out for the thousandth time how every evil passion – snobbery, laziness, vanity, concupiscence, ignorance, greed – is appealed to in these campaigns’ wrote Sayers in her 1942 essay (1948: p. 71).Packard, describing the alleged ‘need’ to stimulate growth in the American economy, appended: ‘What was needed was strategies that would make Americans in large numbers into voracious, wasteful, compulsive consumers’ and ‘The way to end the glut[of commodities] was to produce gluttons’ (1967: 34, 37). In 1940 Sayers complained that, in the modern age, people have lost a sense of personal worth and of the value of service to the community, of work for the sake of contributing to social well-being and for its own intrinsic reward.Thus, people only work to earn money with which to purchase things they do not need, with the consequence that ‘the result of the work is a by-product; the aim of the work is to earn money to do something else’[15]. Packard repeated the complaint, claiming that ‘The lives of most Americans have become so intermeshed with acts of consumption that they tend to gain their feelings of significance in life from these acts of consumption rather than from their meditations,achievements, personal worth and service to others’ (1967: 292).The point, here, is not to engage in an extended critical interpretation of Sayers or Packard but to show that the critique of consumer profligacy is not a post-war phenomenon but is, rather, a running critical subtext in the analysis of modern industrial development.The important thing to note about this critical continuity is that it would not exist were there nothing to criticise: gluttony, voraciousness, profligacy, ignorance: these have been the watchwords of generations of social commentators focusing their disparaging lenses on the ordinary men and women of industrial society.They have been the watchwords because, like us, our parents and grandparents were perceived as wastrels by those commentators.

3. Disposable History

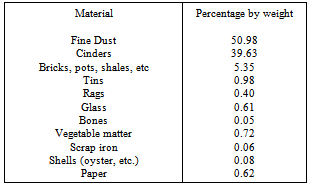

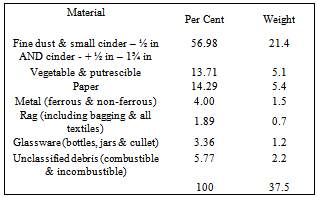

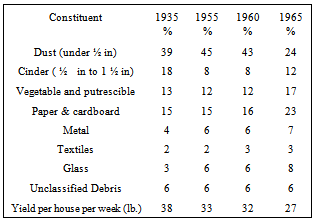

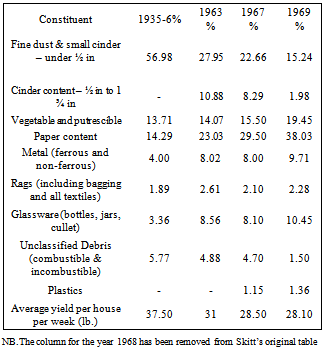

- Official data seem to suggest, and are regularly taken to imply, that household waste generation is growing at an unsustainable rate.Indeed, according to UKDEFRA[3] between 1996/7 and 2002/3 total municipal waste (including non-household sources) appeared to increase from 24.59 million tonnes to 29.31 million tonnes.Total household waste generation appeared to increase from 22.55 million tonnes to 25.82 million tonnes although, as I will explain later, this household fraction of the total is not as straightforward as it appears.No explanation is offered for this enormous increase and DEFRA does not provide any commentary on how it has been possible for householders to process close to 3.3 million extratonnes of waste in just six years. Using Murray’s[11] calculation of the total number of households (24.6 million) this increase represents an extra 134kg per household per annum or about 5.7lbs per week.From where have householders gained the capacity to consume enough extra goods to generate approaching 6lbs more waste every week?Whatever the numbers appear to show there is something mysterious about this incredible rate of growth and here I make some brief comments on whether the statistics really do paint a picture of relentlessly and rapidly rising profligacy.The temptation to view with alarm the apparent increase in household waste is understandable but the alarm needs to be tempered with a realistic assessment of what lies behind it.There are several possible explanations for the apparent growth rate, only one of which demonises consumers and their throwaway mentality.The simplest explanation for increased amounts of household waste may be that there has been an increase in the population during the period.In this case, if the rate of growth of the population equalled the rate of growth of household waste there would be no per capita increase in the total discards.Rather, the increased amount of waste would reflect nothing more than an increased number of people disposing of unwanted items.It is true that England’s (official) population increased between1997-2003 by around 3.5% - approximately from 48.2 millions to 49.9 millions.The rate of growth of the population has been slower than the alleged rate of growth of household waste.Even so, however, it is still the case that a significant proportion of latter’s increase derives from a larger population rather than an increase in consumer profligacy.A second explanation might be that people have become relatively wealthier across the period–either through absolute gains in monetary income or through relative declines in prices.In both cases, increasing amounts of waste might reflect increasing quantities of goods being brought into the house as a consequence of increasing personal wealth.According to the Family Expenditure Survey (2003), average incomes rose by 17% between 1997-8 and 2002-3 with the largest gains being made by lower income groups.However, whilst monetary incomes rose, the evidence on increasing personal wealth is more ambiguous.Certainly, in spite of the gains made at the lower income levels, the inequality gap continued to widen over the same period.Similarly, inflation has eaten away at the real value of the incomes and the rising costs of key items of household expenditure (such as fuel and housing) have had unequal impacts on lower and middle income groups.Whilst there have been some gains in income, on average these have been too small to account for the alleged growth in quantities of municipal waste.The apparent increases in that waste cannot be attributed to wealthier consumers acquiring and disposing of more goods.A third explanation might be that there has been no change in population, no significant increase in wealth but changes in disposal practices.In this case, without any increased material ‘inputs,’ households have consumed less and less, and discarded more and more, of those materials.If this could be confirmed it would indeed demonstrate that the throwaway mentality really had taken hold and in turn would support the moral critique of the effects of consumerism.However, there is not a single shred of evidence to support a claim that contemporary consumers have taken to discarding greater proportions of what they buy.I include these few comments on waste statistics to alert readers to the fact that they do not portray as clear a picture as is often implied in social commentary about contemporary wastefulness.The portrait is blurred by the absence of detailed analysis about what lies behind the rows and columns of numbers.What is true about information on contemporary waste is even moretrue about information relating to historical waste.In particular, historical comparisons are hindered by the absence of any accepted base-line evidence on historical changes either in rates of household waste disposal or in the ratios of the various discarded materials.What evidence does exist, like data on contemporary waste disposal incidentally, is compromised by the use of different classification systems and by attention to different substances found in domestic dustbins.Historical estimates of household waste arisings diverge in their classification systems as much as they differ from contemporary systems.In relation to changing understandings of the character of the waste problem, the available research pays attention to different dustbin contents over time.As I noted above, recent UK government statistics[3] on municipal waste indicate that around 29 million tonnes of municipal rubbish was collected in England in 2000-2001.Of this, almost 3 million tonnes was non-household waste, almost 4.5 million tonnes was collected via civic amenity sites and 2.8 million tonnes was generated by household recycling schemes.In fact, the total waste collected via the dustbin was only 16.8 million tonnes.This figure represents a very small fraction (about 3.5 per cent) of the total (industrial, commercial, agricultural, etc.) annual waste arisings in the UK.DEFRA calculates that, via the dustbin, at the end of the twentieth century, each English household disposed of 15.5-16 kilograms of rubbish each week.This is equivalent to just over 2.2 kilograms or 4.4 pounds per household per day.If you divide the total English dustbin waste for 2001 by the population of England at 2001 (a little over 49 millions) you find that waste-generation per person is 749.6 pounds per annum or approximately 2.05 pounds per day.It is highly instructive to compare this with the figures provided by the National Salvage Council (NSC) for 1918-1919 (quoted in Talbot, 1919: 143-4).The NSC’s conservative estimate was that, for the year following the end of the Great War, household waste arisings stood at 9.45 million tons.According to Talbot’s calculations, this produces a figure of around 1.68 pounds of waste disposed of via the dustbin per person per day, or 613 pounds per annum for every person in Britain.It also needs to be noted that the population that forms the basis of the calculations increased by more than a third in the period between 1921 and the century’s end[9].If the population of England at the end of the Great War were the same as it is today, the conservative estimate of waste arisings collected via the dustbin would have stood at around 13.4 million tons per annum.If we take these figures at face value, and comparing dustbin wastes only, the conclusion must be that between 1919 and 2002 total household waste arisings by weight might have increased by around twenty per cent – although, as we shall see, there are yet more caveats to be entered into the picture.In fact, by weight, the amount of waste disposed of by households fell consistently across the middle part of the 20th century, only returning to early-century levels in the 1970s.The UK Department of the Environment (1971) observed that the weight (and density) of household refuse fell from an average of 17Kg (290 kg/m3) per week in 1935 to 13.2Kg (157 kg/m3) per week in 1968 (Department of the Environment, 1971; see also[6]).Obviously, there have been several social changes in the intervening period – such as the smaller number of occupants per household – but these national average figures for household waste disposal, like Talbot’s calculations of per capita waste disposal, are not markedly dissimilar to the present time.It is tempting to suggest that the weight of household waste fell because of the diminishing proportion of ash and cinder to be found in it.Indeed, this explanation is proffered by the DoE (1971) in the following terms:‘Much of the reduction in weight of refuse has been due to the decline in the domestic consumption of coal and manufactured solid fuel which reduced from 37.5 million tons to 25.5 million tons in the ten years prior to 1967, with a consequent reduction in ash content.’However, the data about the relationships between ash content and weight are contradictory.Skitt (1972: 19) compared waste from households in smoke control areas with waste from households in ‘open fires’ areas and noted that, in spite of the fact that ‘open fires’ household waste had more than double the ash and cinder content of the smoke control households, the overall weight of the waste differed by only half a pound.Flintoff& Millard[6], on the other hand, concluded that the weight of waste produced by households in smoke control areas was almost 25% heavier than the waste produced by ‘normal properties’ even though the two kinds of households generated the roughly the same amount of ash and cinder content. The waste generated from centrally-heated multi-storey flats, on the other hand, was less than two thirds the weight of that produced in the smoke control area.These comparisons of the waste generated in different types of household are interesting in other ways and I return to them below but the point of introducing these data here is to note that it is far from clear that the overall weight of waste changed because of the absence of ash and cinder.

|

|

|

|

4. Concluding Remarks

- What can be concluded from this brief foray into twentieth century patterns of domestic wastage?On the basis of the available evidence, and comparing like with like, in the UK, at least, the claim that the period following the Second World War has been an anomalously wasteful era is somewhat dubious.It is questionable whether the waste crisis is a feature of profligate post-consumption disposal.It is not proven that contemporary consumers are more wantonly wasteful than our predecessors.It is certainly not true that, on the basis of consumer activity, we can contrast our own ‘throwaway society’ to our grandparents’ age of stewardship, carefulness and frugality.In reality, the evidence indicates that our grandparents were as likely to discard reusable items as we are.They were as wasteful – in the social and industrial context of their time – as we are.Even if, to us, our grandparents and their grandparents before them appeared to be more frugal and careful, gross habits of waste and disposal exhibit continuity, not radical change.Indeed, the evidence on urban domestic waste indicates that throwing things away and only partially managing the throwing away process is an intrinsic element of the social organisation of industrial society and is not a peculiarity of our putatively wasteful post-war era.Whilst I would not suggest that ‘waste’ represents no problems at all I would certainly encourage a more serious sociological engagement with its historical reality than is provided in the moral sociology of the throwaway society thesis.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML