-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2025; 15(3): 71-81

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20251503.02

Received: Sep. 9, 2025; Accepted: Sep. 29, 2025; Published: Oct. 25, 2025

Socio-Demographic Factors Associated with Burnout Among Nurses and Midwives in the Yendi Municipality of Northern Ghana

Edward Abasimi1, Seidu Abdul-Razak Tika2, Collins Gbeti2

1Department of Health Science Education, Faculty of Education, University for Development Studies, Tamale

2School of Public Health, University for Development Studies, Tamale

Correspondence to: Edward Abasimi, Department of Health Science Education, Faculty of Education, University for Development Studies, Tamale.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Burnout has been noted to be highly prevalent among nurses of various categories and influences their health and productivity at work. Identifying the socio-demographic antecedents of burnout could help us design or redesign jobs aimed at reducing burnout. This study examined the socio demographic factors associated with burnout among nurses in the Yendi Municipality in the Northern region of Ghana. The quantitative cross-sectional survey approach was used to collect data from 151 nurses and midwives. Using descriptive statistics and ANOVA to analyse the data, results revealed a significant difference in emotional exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy (low efficacy) and overall burnout based on age, marital status and work experience implying the significant influence of these factors on burnout. Significant differences also exist in emotional exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy, and overall burnout with regards to type of means of transport participants used to work with burnout particularly being higher for those who used health facility means of transport (motor bike and vehicle) than those who used other means of transport. Recommendations such as the Ghana Health Service providing more motor bikes to help facilitate the transportation of nurses and midwives to work were made to help minimise burnout and increase the effectiveness and efficiency of nurses in the study area.

Keywords: Socio- demographic factors, Burnout, Nurses and midwives, Northern Ghana

Cite this paper: Edward Abasimi, Seidu Abdul-Razak Tika, Collins Gbeti, Socio-Demographic Factors Associated with Burnout Among Nurses and Midwives in the Yendi Municipality of Northern Ghana, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 15 No. 3, 2025, pp. 71-81. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20251503.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Burnout has generally been considered a threat to nurses’ health and efficiency (Opoku et al., 2023) in the healthcare delivery system and many scholars have reported high rates of it especially among medical nurses (Aiken et al., 2001) with some scholars (e.g. Salari et al., 2020, as cited in Tatala, Wojtasiński, Janowski, & Tużnik, 2025) even reporting it as the highest in nurses among healthcare professionals. In general, the nursing profession has been reported to be stressful and emotionally demanding as the majority of medical duties are carried out by nurses. Nurses perform vital roles in the health sector globally and more so in developing countries such as Ghana. For example, globally nurses have been noted to devote more and quality time serving their clients or patients than any other healthcare provider. The recovery and healing process of patients largely depend on the quality and the nature of the work of nurses (DeLucia, Ott, & Palmieri, 2015). The fact that nurses spend more time with patients potentially leads to burnout and sometimes turnover intentions. This makes the examination of burnout among this workforce critical.The concept of burnout was coined by Freudenberger (1974) as psychological symptoms that arise in human service rendered to human institutions including health facilities as a result of prolonged stress. It has been concluded that symptoms such as irritability, exhaustion, and cynicism are common for people who work for human service organizations (Kacmaz, 2005). There are several definitions of burnout as it applies to humans but the most extensively used definition of burnout is that by Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001). They noted that burnout is not a challenge associated with an individual but a problem of the social environment in which people work and it is a function of how people interact with one another and perform their duties within the working environment. Kacmaz (2005) further explained that the advancement of burnout is the mismatch between the type of work and the characteristics of the individual who does the work. In this study burnout is considered the physical and mental breakdown experienced by nurses and midwives in both private and government hospitals due to pressure and an unfriendly working environment. Burnout is a multi-dimensional illness which comprises three (3) components. These are emotional-exhaustion, disparagement (cynicism) and inefficacy (Maslach et al, 2001).The negative effects of burnout on nurses including its association with turnover and reduction in quality of medical service rendered by them have been reported by previous studies (Xiaoming, Ben-Jiang, Chunchih and Chich-Jen, 2014; Leiter & Maslach, 2009). Previous literature also identified several factors contributing to burnout not just among nurses but employees in general. These include socio-demographic and job related or occupational factors such as workload, lack of social support, lack of or poor accommodation and poor road networks to working places (Oehler & Davidson, 1992). However, previous research had focused on the occupational factors to the neglect of critical socio-demographic or personal factors influencing burnout. Thus, in general there is paucity of research on the socio-demographic factors associated with burnout and more so in the Northern region of Ghana including Yendi, the study area. Research and anecdotal evidence have shown that Ghanaian nurses, like nurses in many other countries experience workload and stress and this potentially predispose them to burnout. The fact that nurses experience great stress and burnout in the Ghanaian context has been demonstrated by the study of Abasimi (2015) which revealed that burnout is real among nurses (and teachers) in selected hospitals and schools in Northern Ghana and that compared to teachers, nurses experienced higher burnout. As a result, the researcher recommended that future studies focus on the nursing profession and particularly on factors associated with burnout among nurses including demographic factors. The finding of Abasimi (2015) is consistent with many other researches in western countries (Maslach, Jackson, & Leiter, 1996) that among various occupational groups, nurses had consistently higher burnout. This makes a study on factors related to burnout among various categories of nurses in the Ghanaian context significant and timely.

2. Literature Review

- Demographic factors such as age, level of education, gender, marital status and experience are potential sources of burnout and turnover intention among nurses in the health sector (Scanlan and Still, 2019; Tatala et al., 2025). Findings of the influence of certain socio-demographic factors such as gender on burnout have generally been mixed or unclear (e.g., Backović, Živojinović, Maksimović & Maksimović, 2012; Bayani, Bagheri & Bayani, 2013, Tatala et al., 2025). As a result, it is empirically prudent to scrutinize the socio-demographic factors influencing nurses' burnout. Moreover, few studies have examined the sociodemographic variables being examined in this study (age, gender, years of working experience, marital status, level of education, category of nursing, type of means of transport to work) in relation to burnout among nurses in general and the study area in particular. This study, therefore, sought to examine the aforementioned socio- demographic factors influencing nurses’ burnout in the Yendi Municipality in Northern Ghana. This study is thus one of the first to examine this relationship in the area. There is preliminary empirical evidence in Ghana that suggests that demographic factors such as gender and age are associated with burnout (Abasimi, 2015; Opoku et al., 2022). However, such evidence in Ghana is scanty. It is on the basis of this that the present study examined the link between certain demographic factors (i.e. age, sex, religion, experience in nursing, marital status, educational level and category of nursing, and means of transport used for work) in relation to burnout. The identification of the relationship between these factors and burnout may help management of healthcare facilities and the nurses themselves develop appropriate intervention strategies to combat stress and burnout among nurses and by extension other health care workers.As indicated earlier, even though a number of previous studies has demonstrated that demographic characteristics such as gender (sex) and category of profession and occupation influence employees’ burnout. (Abasimi, 2015; Adekola, 2013; Adebayo & Ezeanyu, 2010, Kirk-Brown & Wallace, 2004; Olanrewaju & Chineye, 2013), in some instances, the evidence has been mixed thus necessitating further exploration of the relationship and more so in new contexts. For example, whereas Olanrewaju and Chinye (2013) found that male health employees were less susceptible to burnout compared to their females’ counterparts in the Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, the studies of Bakovic, et al. (2012) and Bayani et al. (2013) found gender to have no influence on burnout. Specifically, Bakovic et al. found that gender did not influence burnout components such as depersonalization and emotional exhaustion among final year male and female medical students at the School of Medicine in Belgrade. Bayani, et al. (2013) revealed that age, gender, and working experience did not influence employee burnout. In their systematic review, Chemali et al. (2019) found inconsistent or mixed result regarding the relationship between gender and burnout even though the literature suggest that females are more likely to be burned out that males. They found a number of research reporting that the female gender was a significant predictor of increased risk for burnout (e.g., Abut et al. 2012; Aldrees et al., 2013; Ashka et al., 2010) and only 3 (e.g., Shanafelt, 2002) indicating that male healthcare personnel experience greater burnout. A study conducted by Bryan -Rose and Bourne (2022) among nursing staffers in at a national hospital in Jamaica found age and length of time in the profession significantly associated with burnout. Similarly, the study of Opoku et al. (2022) in Kumasi, Ghana, reveal that age, sex, level of education, years of practice, were associated with all the dimensions of burnout. Specifically, age positively correlated with depersonalization and a negative correlation with personal accomplishment. Gender (sex) and personal accomplishment was also correlated. The authors also reported a positive correlation of educational level with emotional exhaustion.Chemali et al. (2019) reported that the association between age, time in career and burnout were variable. They noted that the relationship between age and burnout is bimodal, in which younger age (i.e. under 25) and old age (i.e. over 55), and higher work experience are associated with higher burnout levels. The reviews highlighted the fact that several studies suggest that younger age was a significant predictor of burnout among various health workers in some countries in the Middle East including Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Israel (Aldrees et al., 2015; Kosan et al. 2018). The review noted that older age was a protective factor for high risk of overall burnout among burn clinicians in Israel. (Haik et al., 2017). On the other hand, the review of Chemali et al. (2019) highlighted several others studies (e.g., Capraz et al., 2017; Rezaei et al., 2018; Abdo et al., 2016) indicating that increasing age and greater occupational experience was positively associated with burnout. Older age was associated with severe burnout among psychiatric trainees in Turkey (Capraz et al., 2017). Higher age and work experience accounted for high variance in depersonalization among nurses in Iran (Rezaei et al., 2018). Burnout was also significantly predicted by age and years of experience among physicians and nurse in Egypt (Abdo et al., 2016) and among healthcare workers in Iran. The mixed findings from the forgoing research on age and years of work experience implies that further research on age and other demographic variables in relation to burnout are necessary in order to help bring clarity.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Settings

- A cross-sectional design involving the quantitative survey approach was used to collect data among nurses and midwives in the Yendi municipality of the Northern Region of Ghana. The municipality has both public and private health facilities in the capital and adjoining communities. These include a government hospital, four (4) health centres, thirteen (13) Community Health and Planning Services (CHPS) compounds, two private clinics and a college of Health Science for training of nurses and other health professionals.

3.2. Participants

- A Multi-stage sampling technique was employed in selecting 151 nurses and midwives (88 female and 63 male) from various health facilities for the study. Two health facilities were selected from a cluster sampling of Twelve (12) health facilities in six suburbs of the Yendi Municipality. In each health facility, participants were recruited using stratified sampling based on sex and nurses’ category (midwives, general nurses and enrolled nurses). Finally, the required number of participants was randomly sampled from their strata of sex and nurse category.

3.3. Study Design and Settings

- A cross-sectional design involving the quantitative survey approach was used to collect data among nurses and midwives in the Yendi municipality of the Northern Region of Ghana. The municipality has both public and private health facilities in the capital and adjoining communities. These include a government hospital, four (4) health centres, thirteen (13) Community Health and Planning Services (CHPS) compounds, two private clinics and a college of Health Science for training of nurses and other health professionals.

3.4. Instruments

- Instruments used for data collection included a demographic questionnaire and an adapted standardised questionnaire for measuring burnout. The demographic questionnaire collected data on age, sex, religion, experience in nursing, marriage, educational level and category of nursing, and means of transport used for work. The Burnout instrument was adapted from the American Public Welfare Association (1981). The original scale consists of twenty-Eight (28) items. The adapted burnout scale however consisted of 20 items. In terms of the slight adaptations made to the scale, certain sentences were rephrased while others deemed not suitable were excluded. This was done to enhance understanding and suitability in the current context. For instance, “I feel angry, irritated, annoyed, or disappointed in people around me” was rephrased to “I feel angry, irritated, annoyed, or disappointed with my patients and their care takers". Bryan-Rose and Bourne (2018) used similar approach in their study in Jamaica. To help in the adaptation of the burnout questionnaire a pre-test was conducted among a small sample of nurses and midwives from a small health facility in the municipality. The burnout scale measured sub-components such as exhaustion, cynicism, and professional inefficacy. Responses were measured using a five- point Likert-type scale 1 (never), 2 (rarely), sometimes (3), 4 (often) or always (5) for each sub-component of the scale. Overall burnout was computed by adding up individual scales used to measure them.

3.5. Reliability and Validity of the Instrument

- The reliability of the adapted scale for burnout was tested using the Cronbach Alpha reliability coefficient which was 0.95 indicating acceptable levels of reliability and was therefore considered suitable for use in the study’s context. Prior to using it pretesting of the instrument was done and the initial finding yielded a Crobach Alpha of .84. Validity of the scale was also ensured by having it reviewed by subject experts and practitioners. In addition, previous studies (Bryan-Rose and Bourne, 2018) reported the validity of the adapted scale. Having determined the reliability and validity of the instrument, it was found suitable for use.

3.6. Data Collection and Analysis

- As stated earlier, data was collected through structured questionnaires which was administered to nurses and midwives in the selected clinics and hospitals within the Yendi Municipality with the help of two trained research assistants after the necessary permission for data collection was obtained. The questionnaire package was distributed to participants during their break periods and portions explained to those who needed it. Respondents were given a maximum of four days to complete the questionnaire for collection by researchers. Data was analysed using descriptive statistics such as percentages and means and inferential statistics such as the One-way ANOVA with the help of SPSS version 23.

3.7. Ethical Issues

- Approval for the conduct of this study was granted by the Ethical Review Committee of the University for Development Studies Institutional Review Board. Participation in the study was voluntary and confidentiality and anonymity of responses were assured. Participants provided a signed informed consent after the objectives and purpose of the study was explained to them. In addition, the Municipal Chief Executive, Regional and Municipal Health Directorate granted their approvals before data collection began.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

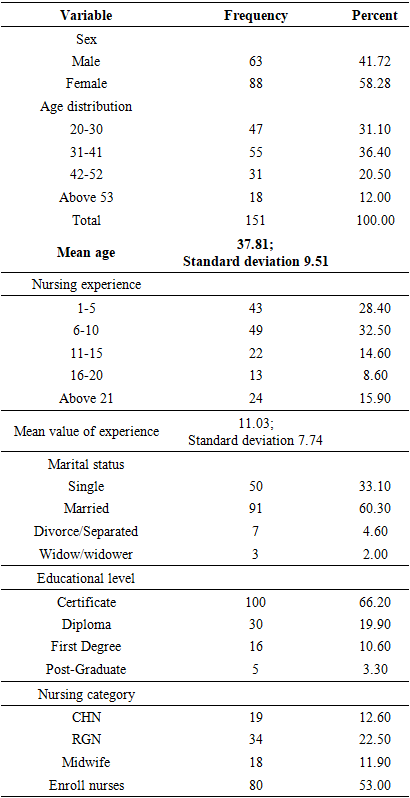

- The demographic characteristics of the sample are as presented in Table 1. Results showed that 58.28% of the respondents were females and 41.72% were males. Forty-seven percent (47%) of the respondents were Christians, 51% and 2% were Muslims and traditionalist respectively. The mean age of the nurses was 38 years. A good number (31.10 %) of the participants had ages ranging between 20-30 years. Those participants whose age ranged 31-41 represented 36.40 % while 20.5% of them had ages within the range 42-52 years and those whose ages were above 53 years were 11.9%.

|

4.1.1 Access to means of Transportation

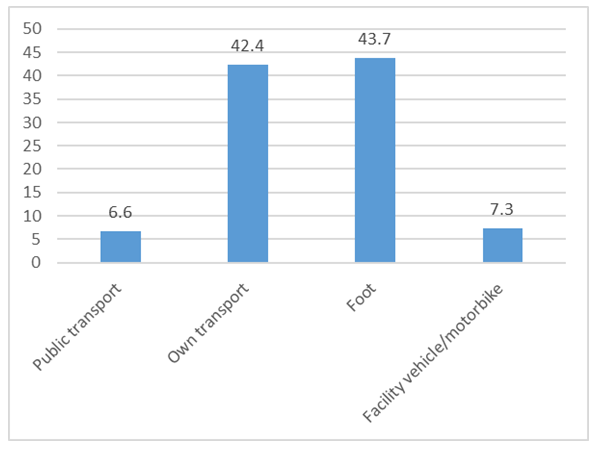

- Access to means of transportation to work for nurses/midwives facilitates effective health care delivery. Figure 1 presents the transport systems nurses and midwives in the Yendi Municipality depended on to commute to their work on daily basis. The results revealed that 6.6% of the participants mainly used public transport whiles 42.4% of them used their own means of transport such as bicycles and motorbikes. A relatively large percentage (i.e., 43.7%) of them walked to their workplace.

| Figure 1. Means of participants’ transport to health facilities |

4.2. Socio - Demographic Factors Associated with Burnout Among Nurses

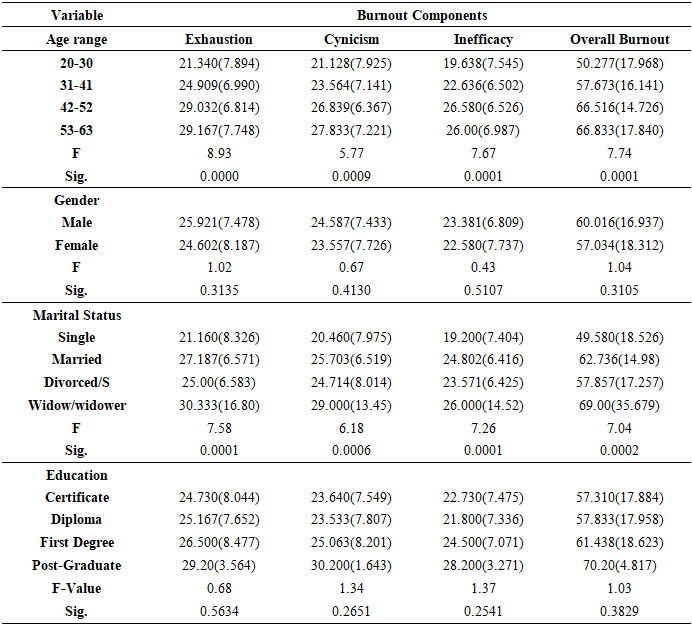

- The study examined whether there were significant differences in burnout among the participants with regards to certain socio-demographic factors. These factors include age, gender and marital status. The One-way ANOVA was conducted to compare the differences in mean levels of these factors among the nurses and midwives. The results are as presented in Table 2.

|

4.2.1. Age Distribution and Burnout

- As shown in Table 2, the findings indicate that there was a significant difference in burnout subscales among nurses and midwives based on age. The descriptive statistics of the age distribution revealed that the mean scores for exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy for the age range of 20-30 were 21.34 (SD = 7.894), 21.13(SD =7.925), and 19.64 (SD =7.545) respectively. The overall burnout of nurses for the age range of 20-30 was 50.28 (SD = 17.968) For the age range of 31-41, the mean scores of the exhaustion, cynicism and inefficacy, were 23.56 (SD = 7.141), 24.91(SD = 6.990), and 22. 64 (SD = 6.502) respectively while the overall burnout was 57.67(SD=16.190). Similarly, the mean scores for exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy for nurses between the ages of 42-52 were 29.03(SD = 6.814), 26.84(SD = (6.367), and 26.58(SD = 6.526)) respectively and the overall burnout score was 66.51(SD = 14.726). Nurses within the ages of 53-63 experienced the maximum level of exhaustion 29.167(7.748), cynicism 27.833(7.221), and inefficacy 26.00(6.987) with overall burnout score being 66.833(17.840).A One-way ANOVA was subsequently conducted to examine whether a significant difference exist in burnout based on the various age ranges. The results revealed a significant difference in overall burnout and its components based on age (P< 0.001). Even though no further analysis were conducted to reveal where the difference lies, it is clear that in general age significantly influence burnout components as well as overall burnout. A closer examination of the means reveals that overall burnout (and each of its component) increased with increasing age.

4.2.2. Gender and Burnout

- Gender plays a significant role in organizational management. Previous Studies have found mixed results with regards to gender and burnout. As shown on Table 2, the findings of the present study revealed that there is no significant difference between male and female with regards to overall burnout and its components. The descriptive statistics revealed that the mean score for emotional exhaustion as 25.921(7.478) and 24.602(8.187). for male and female nurses respectively. For cynicism, males and females scored 24.602(8.187) and 24.602(8.187) respectively while for inefficacy males and females scored 23.381(6.809) and 22.580(7.737) respectively. The overall burnout score for male participants was 60.20 (SD =16.937) and that for female was 50.03 (SD= (18.312).

4.2.3. Marital Status and Burnout

- Marriage comes with responsibilities to both men and women in society. Hence, it could contribute to burnout in society or an organization where a person works. Table 2 Presents descriptive and inferential statistics on the marital status of respondents and their related burnout scores. Single nurses had scores of 21.160(8.326), 20.460(7.975), and 19.200(7.404) for exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy respectfully with overall burnout score of 49.580(18.526). Married respondents reported mean scores of 27.187(6.571), 25.703(6.519), 24.802(6.416 and 62.736(14.98) for work exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy and overall burnout. Respondents who were either divorced or separated reported mean scores of 25.00, 24.71, and 23.57 for emotional exhaustion, cynicism and inefficacy while the overall burnout score was 57.86. The mean score for widows/widowers were 25.00(6.583), 24.714(8.014), 23.571(6.425) and 57.857(17.257) for emotional exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy and overall burnout respectively. The ANOVA results show that burnout scores differ significantly based on marital status. (P< 0.0001). An examination of the descriptive statistics revealed that burnout was high for participants who were widowed followed by those who were married, divorce/separated and single in that order. The ANOVA results show that burnout scores differ significantly based on marital status. (P< 0.0001).

4.2.4. Education and Burnout

- Educational attainment of employee comes with more responsibilities and duties at the workplace hence burnout is expected to be high with increasing educational attainment. The ANOVA results of educational attainment and burnout scores are as presented in Table 2. There was no significant difference between education and burnout among participants. In terms of the descriptive statistics, the mean scores for exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy, and overall burnout for nurses who were certificate holders were 24.73, 23.64, 22.73, and 57.83 respectively. Diploma holders had the mean scores of 25.17, 23.53, 21.80 and 57.83 for exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy, and overall burnout respectively. Nurses who were first degree holders had mean scores of 26.50, 25.06, 24.5 and 61.44 for exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy and overall burnout respectively. The post-graduate nurses reported higher burnout scores than the other certificate holders. The mean scores for exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy and overall burnout were 29.2, 30.2, 28.2, and 70.2 respectively. Even though the descriptive statistics revealed that the burnout of participants increased as their educational attainment increased, the ANOVA result indicate that the differences were not significant.

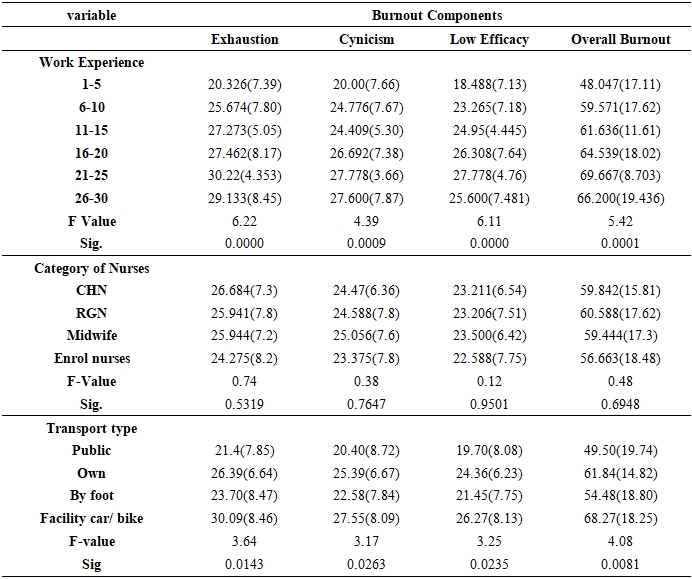

4.2.5. Working Experience in Nursing and Burnout

- The number of years a nurse/midwife serves in a health institution could contribute to effective healthcare delivery. The descriptive statistics and ANOVA of nurses’ experience are as presented in Table 2.1.

|

4.2.6. Category of Nursing and Burnout

- The category of nurses in the study area working in health facilities includes Community Health Nursing (CHN), Registered General Nursing (RGN), Midwives, and Enrolled Nurses. The descriptive statistics and ANOVA result of burnout scores associated with categories of nurses are as shown in Table 2.1. The results revealed that there is no significant difference in burnout among categories of nurses (P >.05).

4.2.7. Types of Means of Transportation and Burnout

- The descriptive and ANOVA results of type of means of transport of nurses to workplaces and burnout are as presented in Table 2.1. The descriptive statistics have shown that nurses who used public, own, walked, or health facility machine (motor bikes) to work had emotional exhaustion of 21.4, 26.39, 23.7, and 30.09 respectively. Nurses who used public transport had an average cynicism score of 20.4, those who used their own means of transport reported a cynicism of 25.39 and those who walked reported 22.58 whiles those who used the health facility machine reported cynicism of 27.55. The average inefficacy for nurses who used public transport, own means of transport, walked or used health facility means of transport (motor bikes) were 19.7, 24.36, 21.45, and 26.27 respectively. The overall burnout associated with various means of transport including public transport, own means of transport, walking, and use of health facility means of transport to work were 49.5, 61.84, 54.48, and 68.27 respectively. The ANOVA results show that there is a significant difference in burnout components (P<.05 and overall burnout (P<.001) based on type of means of transport nurses use to work.

5. Discussion

- The study examined the socio-demographic factors associated with burnout among various categories of nurses and midwives in the Yendi municipality in the Northern region of Ghana. Various factors such as age, gender, marital status and tenure were examined in relation to burnout components of exhaustion, cynicism and inefficacy as well as overall burnout. The findings revealed that there were significant differences in burnout with regards to the socio- demographic variables of Age, Marital status, number of years of work experience (tenure) and type of means of transport used for work. There was no significant difference in the burnout components and overall burnout with regards to the demographic variables of gender, category of nursing and educational level. This implies that in the current study, it can be said that whereas Age, Marital status, tenure and type of means of transport used for work influenced burnout and its components, gender, category of nursing and educational level did not. The discussion that follows examines the effects of the various socio - demographic factors on burnout.

5.1. Age and Burnout

- For Age the average burnout scores show that exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy, and overall burnout were high among nurses whose ages were above 53 years and low for those whose ages were below 30 years. For instance, for the age range of 20-30, the average burnout scores for exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy, and overall burnout, were 21.34, 21.13, 19.64, and 50.28 respectively. It could be observed that as nurses’ age increased burnout score also increased. The fact that burnout significantly differed based on age with increasing age leading to increasing burnout is understandable because as nurses advance in age their social, economic and work demands also increase. This has the potential of putting more emotional and psychological stress on them that could lead to burnout. Accumulated stress due to high job demand may subsequently negatively affect nurses’ productivity at the health facilities.The fact that age is significantly (positively) associated with burnout is generally consistent with previous findings (e.g., Chemali et al., 2019; Opoku et al., 2023, Tatala et al. 2025). For example, Chemali et al. (2019) noted that age influences burnout among health professional at all levels. Al-Sareai, Al-Khaldi, Mostafa and Abdel-Fattah (2013) reported that health workers age was positively associated with emotional exhaustion, and professional inefficacy in Saudi-Arabia. Studies such as that of Kosan, Calikoglu and Guraksin (2018) conducted among 663 physicians revealed that participants who were above 25 years scored higher on emotional exhaustion and inefficacy. Other researchers e.g., (Karakoc et al., 2016; Haik et al., 2017, Tatala et al., 2025) found similar results with Tatala et al. (2025) reporting a significant correlation between age the burnout components of emotional exhaustion and reduced sense of personal accomplishment.

5.2. Gender and Burnout

- Males and females perform different roles in the hospital setting for the safety of patients and good healthcare delivery. Due to different roles the nurses play by gender, it was anticipated that they would experience different levels of burnout. However, even though the findings show that at the descriptive level, males experience a higher overall burnout, emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy than their females’ counterparts, these differences were not statistically significant. This means that gender plays no significant role in burnout among nurses in the study area. This finding is consistent with that of Aldrees, Aleissa, Zamakhshary, Badri, & Sadat-Ali (2013), Aldrees et.al. (2013) and Mudallal, Othman and Al-Hassan (2017) but inconsistent with Sahraian, Fazelzadeh, Mehdizadeh and Toobaee (2008) which found that depersonalization was high among male nurses than their female counterparts. The findings of Sahraian et al. (2008) imply that male nurses are prone to burnout outcomes and this adversely affects their efficiency and the healthcare delivery. According to Maslach et al. (2001), male nurses often experience higher score of cynicism and females score marginally higher on emotional exhaustion. The present finding of no gender difference in burnout among males and females may be attributed to the fact that in the Ghanaian context both male and female nurses perform similar nursing roles.

5.3. Marital Status and Burnout

- The finding of this study also brings to our attention the fact that family status plays significant role in burnout among employees at the work place. The study revealed that marital status had significant effect on burnout with married respondents reporting increased burnout. Further, nurses who were widowed experienced more emotional exhaustion. However, single nurses reported less burnout. This may be because single nurses are more likely to have fewer extra responsibilities compared to those who are married and/or divorce/separated and widowed. This may be because marriage comes with extra responsibilities and duties. Combining such responsibilities with work in any organization could lead to the experience of high levels of stress and burnout since the demands on such an individual would be high as they are torn between “two lovers” (family and work) This finding is however inconsistent with Maslach et al. (2001) which reported high rate of burnout among unmarried workers and employees without children.

5.4. Educational Level and Burnout

- The level of educational attainment of nurses is critical in their contribution to effective delivery of healthcare services. However, it comes with some level of stress which may lead to burnout. The finding of the present study has shown that emotional exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy, and overall burnout increased as nurses’ level of education increased. Post-graduate certificate nurses experienced higher burnout compared to other certificate holders in the profession. This is consistent with the findings of Opoku et al. (2023) in Kumasi of Ghana, which indicated that nurse with postgraduate qualification reported higher burnout (emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation) than those with first degree and diploma. This finding seems to suggest that the higher the level of educational attainment in the profession the higher the experience of burnout. This may not be very surprising as higher level of education may call for more work and greater responsibilities hence the potential for burnout (Maslach et al., 2001). By using randomized cross-sectional data, the study of Patrick and Lavery (2007) corroborated these findings by reporting that nurses with high level of educational qualification experienced intensive emotional exhaustion and cynicism than other trained nurses. All these studies confirm the fact that educational levels influence nurses’ burnout in hospitals. As a result, if measures are not taken to control and/or minimize burnout among these categories of nurses it will lead to high rate of turnover which will affect healthcare delivery.

5.5. Work Experience (Tenure) and Burnout

- Another factor considered in this study was years in the nursing profession (experience in nursing). Many years in the nursing profession comes with higher responsibility to handle medical cases hence, more burnout is expected. The results of this study showed that more experienced nurses in the profession recorded significantly high level of emotional exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy, and overall burnout. This finding is in tandem with Opoku et al. (2023). Whose findings reveal a positive correlation between number of years of work with emotional exhaustion depersonalization and negative relationship with personal accomplishment. Other studies having similar findings include Capraz et al (2017), and Rezaei et al. (2018).

5.6. Nursing Category and Burnout

- Burnout was also examined in relation to the category of nursing. It was anticipated that different type of nurses might experience different levels of burnout. The category of nurses working in hospitals in the study area was Community Health Nurses (CHN), Registered General Nurses (RGN), Midwives, and Enrolled Nurses. The findings show that category of nursing did not significantly affect burnout as all categories of nurses and midwives reported similar level of burnout. This may be due to the fact that all categories of nurses generally perform similar roles and are therefore exposed to similar circumstances in the health facilities. In addition, they are all holistically trained to perform both clinical and preventive healthcare services.

5.7. Type of Means of Transport Used for Work and Burnout

- Finally, type of means of transport nurses used to their various health centres is another factor that could trigger burnout. The finding that type of means of transport had significant effect on emotional exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy and overall burnout suggest that type of means of transport nurses use to work affects burnout. As the findings revealed, nurses in the study area mainly use four tapes of transport system and these had different levels of contribution to burnout among them. The fact that nurses who used health facility motor bikes or cars experienced more overall burnout and all it components than other nurses who used different means of transport could be attributed to the lack of machines such as vehicles and motorbikes at the health facilities to transport to transport them to work as many of them work in distant communities from their places of residence. This is more so considering the fact that even the fewer available motor bikes and cars of some health facilities are not in good condition. This make nurses using health facilities machines to work places frustrated and stressed-up, which could lead to burnout. It may be due to these challenges that most nurses’ resort in the study area use their own means of transport such as motorbikes and bicycles to work. The low burnout among this category of nurses could be due to availability and accessibility to public transport for those working in cities/urban or peri-urban areas.

5.8. Limitations of the Study and Suggestion for Future Studies

- The first limitation of the study is that the study used public hospitals and clinics only instead of both public and private health facilities. The study also concentrated on nurses and midwives instead of all health workers. The study therefore recommends that future studies should assess factors associated with burnout using both public and private health facilities as well as all health workers in the Northern region of Ghana.

5.9. Educational Implications and Conclusions

- This study assessed socio-demographic factors associated with Burnout of nurses in the Yendi Municipality of the Northern Region of Ghana. The findings showed that the components of burnout and overall burnout differed on the basis of Socio-demographic factors such as Age, marital status, work experience and type of transportation used for work. The implication is that these factors affect burnout levels among nurses and midwives in the study area and should be sources of intervention by nurses and management of health facilities in the study area.

5.10. Recommendations

- Based on the research findings and conclusions, the following recommendations are drawn: 1. Based on the fact that the use of health facility machines comes with higher burnout, it is recommended that the Ghana Health Service provide more motor bikes to help facilitate the transportation of nurses and midwives to work. 2. This study used cross-sectional data. It is recommended that further studies target panel data (time series data) to explore the long-term effect of burnout among nurses. 3. Also, studies on macro level should be conducted to have in-depth knowledge of burnout and turnover and how to minimize them in the health sector to enhance quality health care delivery.

6. Conclusions

- This study concludes that a significant difference exists in emotional exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy (low efficacy) overall burnout based on age, marital status and work experience implying the significant influence of these factors on burnout. The study also found significant differences in emotional exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy, and overall burnout with regards to type of means of transport participants used to work with burnout particularly being higher for those who used health facility means of transport (motor bike and vehicle) than those who used other means of transport.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The researchers wish to acknowledge and thank the management of the health facilities where data was collected and all the participants who willingly participated in this study and provided honest responses that made this work possible.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML