-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2025; 15(3): 61-70

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20251503.01

Received: Aug. 25, 2025; Accepted: Sep. 21, 2025; Published: Oct. 10, 2025

Relationship between Self-Efficacy and Interpersonal Nature among Orphaned Adolescent Students in Public Secondary Schools in Kenya

William Agure Otaro, Pamela Adhiambo Raburu, Judith Anyango Owaa

Department of Educational Psychology and Foundations, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Kenya

Correspondence to: William Agure Otaro, Department of Educational Psychology and Foundations, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The purpose of the study was to examine the relationship between self – efficacy and interpersonal nature among orphaned adolescent students in secondary schools in Nyatike Sub - County, Kenya. The study was informed by Self-efficacy theory adopted from Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory. Mixed Methods research design within Mixed Methods Approach was utilized and Concurrent Triangulation was used. The target population consisted of 1703 students, 17 teachers and 3 Focus Group Discussions from 57 public secondary schools in Nyatike Sub- County of Kenya. A sample size of 511 students, 17 teachers and 12 participants for Focus Group Discussions were obtained using stratified random sampling and purposive sampling techniques respectively. Reliability of instruments was determined through pilot study with 42 participants. The participants in the pilot study were excluded from taking part in the actual study. Content and face validity of the instruments was ascertained by pilot testing of the questionnaires and also by seeking expert opinion of university lecturers experienced in formulation of research tools. Data was collected using closed-ended questionnaires, in-depth interviews and Focus Group Discussions. Quantitative data was analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics while qualitative data was analyzed using thematic framework. The study findings revealed that there was moderate positive (r=0.370, p=0.01) correlation between self – efficacy and interpersonal nature of orphaned adolescents. The study concluded that self-efficacy could be enhanced to foster better interpersonal functioning among orphaned adolescent students.

Keywords: Self-efficacy, Interpersonal nature, Orphaned adolescent, Secondary school

Cite this paper: William Agure Otaro, Pamela Adhiambo Raburu, Judith Anyango Owaa, Relationship between Self-Efficacy and Interpersonal Nature among Orphaned Adolescent Students in Public Secondary Schools in Kenya, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 15 No. 3, 2025, pp. 61-70. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20251503.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Adolescence represents a pivotal period of psychological development characterized by increasing autonomy, identity formation, and evolving social dynamics. For orphaned adolescents, the absence of parental figures and consistent caregiving environments may introduce unique psychosocial challenges that impact interpersonal nature. Central to adaptive development during this stage is the construct of self-efficacy – defined as an individual’s belief in their capability to organize and execute actions required to manage prospective situations [1]. Equally important is the interpersonal nature of adolescents, encompassing their ability to initiate, sustain, and navigate social relationships, which plays a critical role in emotional regulation and psychological well-being. Interpersonal nature is a person’s natural tendency or style in dealing with others; that is how a person is inclined to interact, connect and relate with other people around them. In this study it touches on orphaned adolescents’ interaction, connection, and communication with peers, teachers, and guardians. Self-efficacy is influenced by four primary factors: Social persuasion pertains to the encouragement and positive feedback a person receives from other people can boost self-efficacy but discouragement can decrease it. Mastery experience is the confidence that one achieves on successful completion of a task. Vicarious experience is hinged on the increase of one’s belief in their ability based on observations that they make when others perform a task, and physiological and emotional states relate to a person’s physical and emotional state which can affect the belief in their capabilities [1].

1.1. Statement of the Problem

- Interpersonal relationships are central to personal, social, psychological and professional success, yet individuals differ significantly how they initiate, maintain and navigate these connections. High self-efficacy often exhibit confidence, persistence and proactive problem-solving while lower self-efficacy may be associated with social withdrawal, difficulty in expressing needs, or heightened interpersonal conflicts. Lack of clarity how self-efficacy impacts interpersonal nature among orphaned adolescents poses a gap in psychological and behavioural research. The present study examines the relationship between self – efficacy and interpersonal nature among orphaned adolescents, with the aim of elucidating how perceived personal competence may influence social engagement and relational outcomes within this vulnerable population. A study in Indonesia explored direction of self-efficacy for the past ten years. The study was based on content analysis of research articles published in google.scholar. The study found that self-efficacy has influence on personal, academic and career areas [2]. Another study in South Africa found that maternal death has negative impact on psychosocial well-being of children even when they have crossed the 18-year threshold. Yearning for their mothers greatly affected their ability to develop coping strategies [3]. In Ethiopia, an examination of psychological well-being of adolescent orphans established that orphanhood was associated with high emotional and hyperactivity symptoms, lack of social skills and anti-social tendencies or depression [4].

1.2. Objectives

- [a] General objective: To examine the relationship between self-efficacy and interpersonal nature among orphaned adolescent studentsSpecific objectives: [b] To investigate the influence of social persuasion on interpersonal nature of orphaned adolescent students[i] To assess the role of mastery experience in shaping the interpersonal nature of orphaned adolescent students[ii] To determine how vicarious experience contribute to the interpersonal nature of orphaned adolescent students[iii] To analyze the effect of physiological and emotional state on the interpersonal nature of orphaned adolescent students

1.3. Research Hypothesis

- The null hypothesis of the study was: There is no significant statistical influence of self-efficacy on interpersonal nature of orphaned adolescent students.

2. Theoretical Framework

- The study was informed by Self – efficacy theory adopted from Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory. Self – efficacy theory posits that individuals’ beliefs in their capability to execute specific tasks significantly influences their motivation, behaviour, and psychological well – being. The theory identifies four primary sources of self - efficacy: verbal persuasion, mastery experience, vicarious experience and physiological or emotional state. Higher self-efficacy is associated with greater resilience, persistence, and confidence when facing challenges [1]. In orphaned adolescent students, self-efficacy may play a critical role in shaping how they perceive themselves and interact with others. Limited exposure to stable support systems may affect their access to the key sources of self-efficacy, potentially influencing both their self- beliefs and their interpersonal functioning. This study explores how variations in self-efficacy among orphaned adolescents may relate to their ability to form and maintain healthy social relationships, offering insights into the psychological mechanisms that support or hinder social development in orphaned adolescent students.

2.1. Literature Review

- The impact of adults’ interaction moves and strategies on orphan children’s participation and agency was analyzed in a study in Italy [5]. Using a sample of 14 orphans and 11 educators, the study established that in stable patterns of adult-child interaction recurring across different activities, adult strategies impact on orphan children’s participation and agency. However, the study sample was quite small which make findings difficult to be generalized to a larger population.An investigation of elements of social well - being index for orphan and vulnerable adolescents established that self-efficacy was a contributor to learning ability among orphans in Malaysia. The study used questionnaires to collect data from 270 participants [6]. However, the use of quantitative data only denied participants the opportunity to express their feelings and opinions. The present study sought to bridge the gap by using mixed methods to get insight into orphaned adolescents’ feelings and opinions about their challenges and how they manage situations.On exploring government effort to empower orphan children with aim to develop social work programme, a study reported that orphans had low self-efficacy because they relied on support from government, non-governmental organizations and well-wishers [7]. However, in Afghanistan it was reported that orphaned children were motivated to achieve higher education levels despite the challenges they experienced [8] while a study in Pakistan found that self-efficacy correlated positively with sub - scales of control of origin and adversity quotient among orphan children [9]. In addition, another study in Nigeria revealed that self-efficacy predicted academic performance among orphaned secondary school students [10]. The study used questionnaires to collect data from a stratified purposive sample of 338 participants. However, the study lacked qualitative data which limited the results to numerical data only. Stratified purposive sampling also has potential bias in selection of participants as the researcher may unconsciously favour certain individuals or characteristics within the sub-groups. The present study used mixed methodology approaches with a randomly determined sample so as to delve into respondents’ opinions and feeling.Psychological challenges among orphaned adolescents were assessed in a study in Egypt. [11]. The study adopted descriptive research design and comprised a sample of 93 participants selected using convenient sampling technique. The study established that two-thirds of respondents exhibited low self- efficacy while more than half of the respondents experienced psychological challenges of achievement, success, and need for social appreciation, stress, anxiety, depression and low-self – esteem. The study used a small sample selected using convenient method which may pose lack of diversity as certain groups may be over or under-represented, since participants with similar background may be included and can lead to confounding of variables that skew the results, making it difficult to isolate specific factors or draw accurate conclusion. The present study used a larger sample drawn using randomization to get rid of bias in selection of participants.Further, a scrutiny of the relationship between self-efficacy and academic performance, and transition among orphaned children indicated that self – efficacy was associated with better academic performance and greater likelihood of transitioning to post- primary educational institutions [12]. The sample comprised of 1410 orphans aged 10 to 16 years and drawn from primary schools in Uganda. The study adopted longitudinal research design which has limitations which might affect reliability of responses since some respondents might be lost during data collection process due to relocation of residence, transfers or natural attrition. The present study bridged this gap by utilizing one-off method of data collection such as questionnaires, interview and focus group discussions.A study in Kenya established a positive relationship between guidance and counselling and self-efficacy among orphans [13]. Descriptive survey research design was adopted and a purposive sample of 240, 20 care-givers and 20 orphanage administrators were recruited in the study. However, purposive sampling technique could introduce personal bias which can influence results and affect external validity of the study. The present study employed stratified random sampling to take care of bias that might arise from participant selection process.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

- The present study employed Concurrent Triangulation Design within Mixed Methods Approach. Quantitative approach used in the research was based on variables that were measured through numbers and were analyzed using procedures of statistical nature [14]. Quantitative approach allows a clear collection and interpretation of data in the context of the study and easy understanding of findings [15] Qualitative approach was used to collect data and were analyzed thematically [16].

3.2. Participants

- The target population for the study consisted of 1703 orphaned and vulnerable form 3 students, 68 class teachers and 61 Heads of Departments of Guidance and Counselling in 57 public secondary schools in Nyatike Sub – County of Kenya. Cluster sampling was used to sample 17 public secondary schools into administrative divisions so as to achieve fair representation of respondents from all the regions of the Sub – County. A sample of 511 orphaned adolescent students were selected using proportionate and stratified random sampling technique, while purposive sampling technique was used to sample 8 class teachers and 9 Heads of Guidance and Counselling departments in the sampled schools. The sample size was deemed appropriate because it formed 30% of the target population [17,18]. Thus, 511 was an adequate sample and its information can be generalized to a general population. A sample of 12 orphaned and vulnerable students were selected from the sampled schools for Focus Group Discussions, and 17 teachers were selected using purposive sampling technique for in-depth interviews. Purposive sampling was suitable for the present study because it is primarily used in qualitative studies in which selecting units (individuals, groups of individuals, institutions) based on specific purposes associated with answering research questions [19].

3.3. Research Instruments

- Quantitative data from orphaned and vulnerable adolescent students was collected using a validated 24-itemized Self-Efficacy rating scale consisting of 8 items for each of the factors influencing self-efficacy: social persuasion, mastery experience, vicarious experience and physiological and emotional state were used to collect data from orphaned adolescents. Data for interpersonal nature was collected using a 24-itemized validated self-report rating scale designed to measure perceived interpersonal traits. The responses were designed on 5-point likert scale from highest to lowest: Strongly Agree (SA), Agree (A), Undecided (U), Disagree(D), Strongly Disagree (SD). In-depth interviews schedules were used to obtain detailed information from class teachers and heads of department of Guidance and Counselling in the sampled schools. Additional qualitative data was provided by Focus Group Discussions guides. To determine the suitability of the instruments, the researcher adopted expert opinion of lecturers of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology from department of Educational Psychology for verification and feedback during seminar presentations.

3.4. Data Collection Procedures

- Data collection procedure began after proposal was accepted and approved by the university supervisors. An introductory letter was obtained from the Board of Postgraduate Studies of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology. Permission was sought from the National Commission for Science Technology and Innovation which allowed the researcher to proceed to the field to collect data. Ethical considerations that included voluntary participation, privacy of possible and actual participants, consent and confidentiality of data were adhered to. Questionnaires were issued to the students while interviews were held with class teachers and heads of Guidance and Counselling departments in the schools, and Focus Group Discussions to collect qualitative data was held with orphaned students because it enabled researcher to understand and interpret feelings and opinions based on experiences of participants, and the responses were audio - recorded for analysis. Quantitative data was collected from 458 students using questionnaires while qualitative data was collected from 9 class teachers, 8 heads of Guidance and Counselling, and Focus Group Discussions were held with 12 orphaned adolescent students.

3.5. Data Analysis

- Quantitative analysis involved the use of descriptive and inferential statistics which allowed the researcher to obtain and present data in statistical format so as to facilitate identification of important information derived from research questions. Qualitative data were transcribed from 17 audio - recorded interviews which were listened to again and again so as to check for any incompleteness, inconsistency or irrelevance of data [20]. Transcriptions were made, and were analyzed using thematic analysis [21].

4. Results

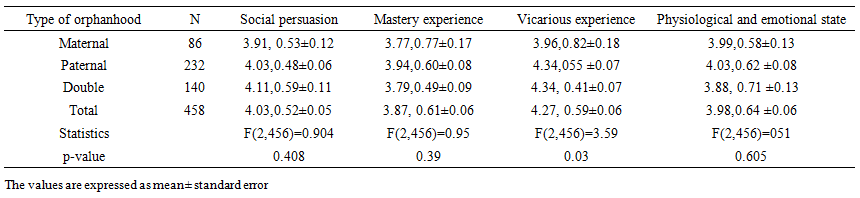

- The sample consisted of 458 adolescent orphans; males 226 (49.3%) and females 232 (50.7%) with ages ranging 17-20 years (M=18.08, SD=0.98). Social persuasion questionnaire consisted of 8 items based on five - point likert scale. The result showed that the degree of influence of social persuasion among adolescents was high (mean = 3.06) as indicated by most respondents, with all indicators rated high (mean ranging between 2.68 and 3.51). Table 1 indicates results on sources of self-efficacy. Social persuasion registered overall mean 4.03, SD = 0.52; with maternal (M=3.91, SD=0.53), paternal (M= 4.03, SD=0.48) and double (M=4.11, SD=0.59). Analysis of variance was computed to compare levels of social persuasion among double, paternal and maternal orphaned adolescents. The result indicates that there was no significant statistical difference between mean scores (F2,456) =0.59, P=0.41).

| Table 1. Self-efficacy sources group statistics |

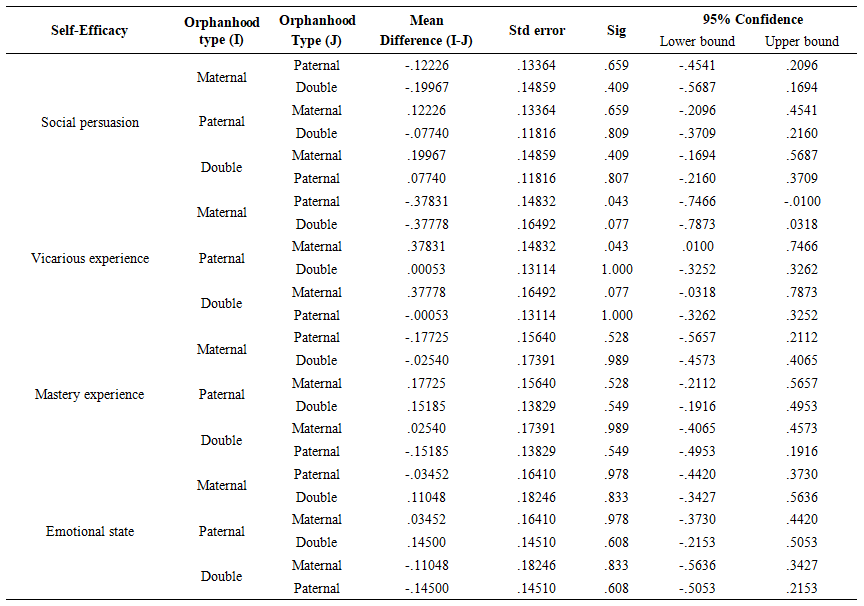

| Table 2. Post hoc test on sources of self-efficacy |

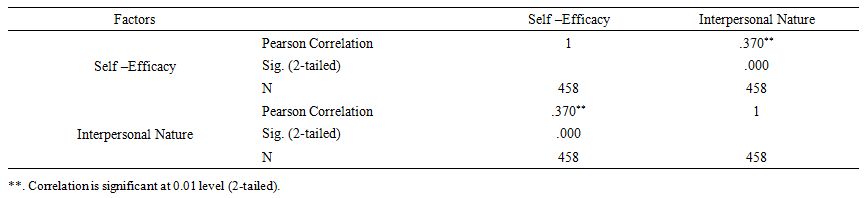

| Table 3. Correlation Analysis between Self -efficacy and Interpersonal nature |

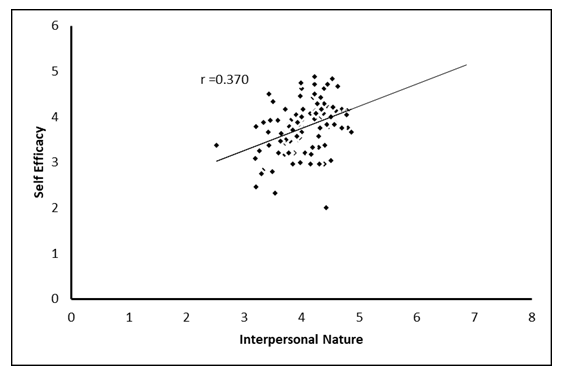

| Figure 1. Scatter plot for Correlation between Self-efficacy and Interpersonal Nature |

5. Discussion of Findings

- The study sought to examine the relationship between self-efficacy and interpersonal nature among orphaned adolescent students in public secondary schools in Nyatike Sub -County, Kenya. Four primary sources of self-efficacy: social persuasion, mastery experience, vicarious experience, and physiological and emotional state were investigated. The study employed both quantitative and qualitative data which were collected through questionnaires, interviews schedules and focus group discussions guides. The result on the contribution of social persuasion to self-efficacy showed that social persuasion bolstered self-efficacy belief among orphaned adolescent learners. This result was consistent with finding by a study that agrees that orphans are able to develop positive acceptance of change and good relations with others [22]. A study in China concurs that social persuasion significantly improved social support for orphans as majority of orphans, (52.63%) attributed their motivation to work hard in school to verbal encouragement and positive feedback they received from their teachers [23].The result in Table 1 shows that orphans demonstrated higher level of social persuasion. Further, double orphans showed higher level of effect of social persuasion compared to other categories of orphans. The result was in agreement with the finding of a study which asserted that informal conversation had marginal effect on socialization and self-efficacy among orphaned children [5].ANOVA results in Table 1 indicate that there was no significant statistical difference between mean scores (F2,456) =0.59, P=0.41). This implies that orphaned adolescents are positively or negatively influenced by social persuasion that goes on around them. The result was in line with findings by a study in Nigeria that agrees that social persuasion predicted academic performance among orphaned students [10]. Further, a study in Kenya found that career guidance services have substantial influence on self-efficacy among orphaned students [24]. Qualitative findings from Focus Group Discussions showed that positive feedback from teachers enhanced self-efficacy belief among orphaned adolescents. Social persuasion develops positive self - image and makes orphaned learners feel accepted by their teachers. This was noted in the remark, ‘I try to work hard in school because there are teachers who encourage me. Teachers always tell us we do not need to come from rich families to succeed in life’ [OA6].The sentiments of OA6 imply that orphaned adolescent learners have formed rapport through transactional conversation. Social persuasion can strengthen an individual’s belief in their own capabilities. When students receive encouragement, they are likely to believe in their own abilities and put much effort into their studies. The following was a respondent’s remark from focus group discussion:‘I normally listen and take in teachers’ advice on my performance. I consider all remarks made about my performance by teachers are positive feedback meant to help me reflect and improve on my performance.’ [OA5]The views by OA5 shows the role of social persuasion in building self-efficacy. The student demonstrates an openness to external encouragement and guidance. The teachers feedback in interpreted as a motivation to reflect and improve, which contributes to stronger sense of personal efficacy and belief in their ability to succeed.The result on contribution of mastery experience indicates that participants generally often perceive themselves as capable of handling tasks successfully. This implies that orphaned adolescent students are likely to develop stronger confidence in their abilities which can positively influence their performance and interpersonal outcomes.The result in Table 1 indicates paternal orphans demonstrated higher mastery experience. This conforms with the assertion that double orphans exhibited significantly lower psychological well- being than half orphans [25]. Similar finding was reported by a study in Ethiopia that too asserted that double orphans significantly showed higher self-efficacy status than single and non-orphans [26]. On the contrary, a study in Pakistan found that orphans, in comparison to non-orphans, demonstrated diminished self-esteem which negatively impacted their well-being [27].Analysis of variance result indicates that all categories of orphaned adolescents gained new ideas and skills from mastery experience. This result was in agreement with finding of a study in Malaysia that found that self-efficacy mediated positive feedback on learning ability of orphaned adolescents [6]. The finding of a study in Indonesia also indicated that self-efficacy has influence on personal and academic outcomes [2]. However, a study in Pakistan found no differences in self-efficacy between orphans and non – orphans [28]. Qualitative findings revealed that orphaned adolescents were motivated to perform when their school test results were good. This was noted in the remark, ‘Most learners are motivated whenever their performance seems to be on the upward trend’ [CT3]. The statement by CT3 indicates that mastery experience is a positive predictor of self-efficacy belief. This result was supported by finding of a study in Indonesia which reported that orphaned children were motivated to achieve higher levels of education [29]. Similarly, a study in Afghanistan found that the quest for education was high among orphans despite the challenges of distraction and day dreaming [8].The result on vicarious experience shows that maternal orphans registered lowest mean and greatest variability indicating they may be experiencing more challenges and wider range of outcomes in vicarious experience. This result implies that orphaned adolescents put more effort when they work together in groups which allow them the opportunity to observe one another as they perform tasks. This finding is supported by a study in Indonesia that reported that vicarious experience directly influenced self- efficacy on performance in Mathematics among orphaned high school students [30]. Another study in Kenya reported that engaging with peer and family support along with volunteering in one’s community play important roles in modelling orphaned adolescents’ experiences [31].The result further shows that there is significant statistical difference in mean scores between orphan categories. The finding was consistent with that of a study in Iraq that found that there existed mean difference between half and double orphans in every dimension [32]. Similar results were reported by a study in India which asserted that double orphans showed significantly lower overall psychological well-being compared to half orphans [25]. Qualitative findings showed that orphaned adolescents felt capable of succeeding in education because others in similar conditions have made success. This was shown by the verbatim expressions of respondents as the following: ‘It is possible to do well even in final examination because others have also succeeded yet they were orphans’[OA8]. Another student remarked, ‘I always work hard to succeed just as the other students have done’ [OA2].The sentiments of OA8 and OA2 imply that orphaned adolescent students are propelled to work hard when they observe their peers or models succeed in similar tasks. This fact is accredited by findings of study conducted in Indonesia that reported that successful people tended to continue to seek success [2]. Further, a study in Malaysia observes that orphans exhibited positive social skills and attitudes [33]. However, a study in Ethiopia asserts that orphaned adolescents were exposed to diverse psychological problems that affected their emotions and education [34]. This view is resonated by findings reported by a study in Kenya that found that majority of orphaned children (76.3%) were diagnosed with anxiety disorder [35].Physiological and emotional state results shows that double orphans showed slightly lower mean score and exhibited greater variability compared to single orphans. This finding suggests that double orphans may be at modest disadvantage and present more diverse experiences. The result concurs with finding of a study in Nepal which found that orphaned students registered low self-esteem during their learning [36]. Similarly, a study in Kenya observes that emotional and social well-being of orphaned adolescents was greatly disrupted by death of parents [37]. Further, the findings by a study in Ethiopia too asserted that double orphans significantly showed higher self-efficacy status than single and non-orphans [26]. On the contrary, a study in India argues that there was no significant statistical difference between emotional intelligence of orphaned students [38]. Finding of a study in South Africa argues that orphaned students actively seek support for their physical and psychological needs, engage in constructive tasks and foster supportive relationships for their psychological well-being [39].Qualitative findings obtained from interview transcripts and analyzed on how orphaned students relate with others in school showed that orphaned students kept their emotions in check by maintaining healthy relationships with other students, teachers and guardians. However, orphaned students prefer confidentiality about their challenges. This was revealed by assertions by guidance and counselling teachers as in the following excerpts: ‘When a student knows you (teacher) care about them and talk to them with love, they always confide in you [teacher]’ [GT7]. The students also like their challenges to be treated with confidentiality. Another teacher remarked, ‘They don’t like their difficulties to be known to everyone.’ [GT4]. Teachers are important component of school environment as they play surrogate parents in school, and many learners rely upon their advice and emotional touch. Verbatim quotes from GT7 and GT4 indicate a strong feeling in support of confidentiality on how orphaned adolescents’ issues are handled as it imparted a sense of self – esteem and self – worth in them, and a feeling of trust with their teachers. This finding concurs with that of a study in South Africa which revealed that supportive teachers’ words of encouragement enhanced confidence and emotional regulation in orphaned learners that they felt motivated to continue school even in difficult situations [39]. A similar finding was also reported by a study in Zambia that found that high teacher-student in-class communication enhanced love and empathy in orphaned learners [40]. The analysis of variance result indicates that there was no significant statistical difference between mean scores F(2, 456) =0.51; p=0.61). Double orphans showed slightly lower mean score and exhibited greater variability compared to single orphans. This finding suggests that double orphans may be at modest disadvantage and present more diverse experiences. The finding concurs with that of a study in Nepal which found that orphaned students registered low self-esteem during their learning [36]. A study in Kenya too observes that emotional and social well-being of orphaned adolescents was greatly disrupted by death of parents [37]. On the contrary, a study in India argues that there was no significant statistical difference of emotional intelligence among orphaned students [38]. Table 2 shows result for Scheffe’s post hoc test carried out to confirm the differences that lie between pairwise orphan groups. The result indicates that in social persuasion, double orphans scored significantly higher than maternal orphans. The result implies that verbal persuasion does not significantly differ between any pair of the groups (p>.05). In mastery experience, paternal orphans registered higher (3.94, SD=0.60) than both maternal (M=3.77, SD=0.77) and double orphans (M=3.79, SD=0.49). This implies that orphan status did not significantly influence mastery experience in the sample. In vicarious experience, both paternal and double orphans registered higher scores than maternal orphans. Maternal orphanhood may be a particular vulnerability since maternal orphans registered lower vicarious experience compared to paternal (mean difference =-0.38, p=.043). This implies that absence of mothers presents unique emotional and practical consequences such as reduced nurturing support, caregiving or household stability. None of the pairwise group differences were statistically significant in physiological and emotional states. The finding suggests that the experience of losing both parents is qualitatively different from losing only one parent as emotional state appears relatively stable across orphanhood categories in this sample.Table 3 indicates that a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of r=0.370 was obtained. This shows there is a moderate positive (r=0.370, p=0.01) correlation between self-efficacy and interpersonal nature. Although the correlation is moderate, it follows that self-efficacy is effective in developing an enduring interpersonal nature. Figure 1 demonstrates that self-efficacy is effective in development of positive interpersonal nature among orphaned adolescent students. The null hypothesis which stated that ‘there is no significant statistical influence of self-efficacy on interpersonal nature among orphaned adolescents’ was rejected and the alternative hypothesis was accepted since it was established that there was a statistically significant relationship between self – efficacy and interpersonal nature. The finding concurs with that of a study in Egypt which found that there is positive relationship between self – efficacy and psychological adjustment among orphaned adolescents [11]. Similarly, a study in Indonesia adds that self – efficacy is positively and significantly related to psychological well-being among orphaned adolescents [30]. Further, a study in Kenya augments that positive and significant relationship exists between self – efficacy and guidance and counselling services [24]. However, a study in Egypt asserts that low level of self – esteem in orphans affects their interpersonal well-being [41]. On the same breath, a study in India argues that orphans are overly distressed that they are unable to concentrate in school [42].

6. Limitations of the Study

- The empirical results reported in this study should be considered in light of some limitations. The primary limitation to the generalization of these results is that the participants were recruited from selected secondary schools in one sub-county. Thus, the findings may not apply to all other orphaned adolescent students in other regions. Secondly, the possible bias in data on self-report questionnaires and interviews may be influenced by social desirability bias or inaccurate self-perceptions. Lastly, the study was based on cross-sectional design and data was collection at one point in time. Thus, it could not establish causality as only associations between self-efficacy sources and interpersonal nature were investigated.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The study findings revealed that there was a statistically significant relationship between self – efficacy and interpersonal nature. A Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r=0.370, p=0.01) was arrived at. This indicates that a moderately positive correlation exists between self – efficacy and interpersonal nature of orphaned adolescent students. Sources of self-efficacy; social persuasion, mastery experience, vicarious experience and emotional state each have a share of contribution to effective development of self – efficacy belief. The study concluded that self – efficacy plays an important role in fostering effective interpersonal interactions. In view of the results, the study recommends creation of systems that encourage positive feedback and recognition, offer guidance to students struggling with self-doubt, and integration of confidence -building programmes to strengthen interpersonal relations.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML