-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2025; 15(2): 56-59

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20251502.03

Received: Jul. 3, 2025; Accepted: Jul. 21, 2025; Published: Jul. 23, 2025

The Implications of the Contextualization of Scales for the Measurement of Sense of Coherence

Jacek Hochwälder

Department of Psychology, Mälardalen University, Eskilstuna, Sweden

Correspondence to: Jacek Hochwälder, Department of Psychology, Mälardalen University, Eskilstuna, Sweden.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Scales are an important part of research and practice in psychology and other health and social sciences. When measurements obtained from scales are used as predictors, it is desirable to optimize their predictive validity. One way the latter can be enhanced is by contextualizing the measurements of the predictors to the domain of the outcomes. The present theoretical study focuses on the methodological issue of contextualization of scales, and it´s aim is to: (1) give a brief review of the contextualization of scales, and (2) suggest some implications of the contextualization of scales for the measurement of sense of coherence (SOC), which is the core construct in Antonovsky’s salutogenic model of health. This study highlighted some central topics related to contextualization, presented findings from previous research which indicates that contextualization can improve predictive power, provided examples of contextualization of SOC for various domains, and suggested topics for future research. It was concluded that contextualization of measurements is an important methodological aspect that should be considered in both research and practice, and that it should be investigated if contextualization of SOC will increase predictive validity, when SOC is used as a predictor variable, and sensitivity to change, when SOC is used as an outcome variable.

Keywords: Contextualization, Domain-specific Scales, Predictive Validity, Sense of Coherence

Cite this paper: Jacek Hochwälder, The Implications of the Contextualization of Scales for the Measurement of Sense of Coherence, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 15 No. 2, 2025, pp. 56-59. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20251502.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Measurements obtained by scales are fundamental to much research and practice in psychology and other health and social sciences. Both in research and practice it is desirable that the predictor variable has high predictive validity. The latter can be enhanced by contextualizing the scale that is used to measure the predictor variable. A scale that is used to measure the predictor variable is contextualized or made domain specific by asking people to respond to questions or items with reference to the context or domain of the outcome variable. The aims of the present text are: (1) to give a brief review of the contextualization of scales, and (2) to suggest some implications of the contextualization of scales for the measurement of sense of coherence, which is the core construct in Antonovsky’s salutogenic model of health [1-3].

2. Contextualization of Scales

- Several scholars have suggested that context or domain-specific measures or scales should be stronger predictors of outcomes in the given context or domain than broad global or general measures or scales. This suggestion is expressed in the principle of compatibility [4], the specificity matching principle [5], the fidelity-bandwidth trade off [6], and the frame of reference effect [7]. The main theoretical argument why domain-specific scales should predict domain-specific outcomes better than general scales is that a person´s behaviour in a domain is a function of both the personal characteristics and the domain, which is in alignment with the fundamental postulate of interactional psychology and the theory of conditional disposition. According to interactional psychology, human behaviour is assumed to be a function of the person-by-situation interaction [8]. Similarly, according to the theory of conditional disposition, the manifestation of a personality trait or disposition is conditioned upon the situation or context [9]. There are also methodological arguments why domain-specific scales should predict domain-specific outcomes better than general scales. One argument is that the use of domain-specific scales should allow a greater sensitivity to differences in a specific domain that may be blurred by a general scale [10]. Another argument is that domain-specific measures may be less likely to produce within-subjects inconsistencies and may also reduce the presence of between-subjects variability in the interpretations of items [11]. A scale can be made domain specific or contextualized by asking people to respond to questions or items with a particular context in mind. There are three main methods that can be used to contextualize items: (1) Item contextualization, where general items are contextualized by adding a tag (e.g., modifying “I am lazy” into “I am lazy at work”); (2) Instruction contextualization, where general items are contextualized by giving the context in the introductory instruction to the scale (e.g., Instructions: “Answer the following questions with regard to how you usually feel, think and behave at work:” “I am a lazy”); (3) Complete contextualization, where items are specially designed to measure a given construct in a given context (e.g., “People think I don’t work hard”).Research that compares the three types of contextualization is scarce. In one study, Holtrop et al. [12] compared item contextualization with complete contextualization and found, inter alia: (a) that item contextualization is easier and less time-consuming to implement than complete contextualization, but; (b) that respondents experienced the complete contextualization to have more face validity, predictive validity, and “liked” it more than the item contextualization, and; (c) that the complete contextualized measures predicted more variance in the criteria than the item contextualized measures. There is empirical evidence - for some predictors, outcomes, and domains - that domain-specific scales, predict better domain-specific outcomes than general scales. For example, Shaffer and Postlethwaite [13] concluded, based on the findings from their meta-analytical study, that workplace-contextualized measures of the big five factors of personality are more valid predictors of supervisory ratings of job performance than the corresponding non-contextualized measures. Pajares [14] found, in his literature-review study, that academic self-efficacy is a better predictor of various academic outcome variables (e.g., grades) than general self-efficacy. Wang et al. [11] found, in their meta-analytical study, a stronger relationship between the work locus of control (LOC) and various work-related outcome variables (e.g., job satisfaction) than between general LOC and these work-related outcome variables.

3. Implications for the Measurement of Sense of Coherence

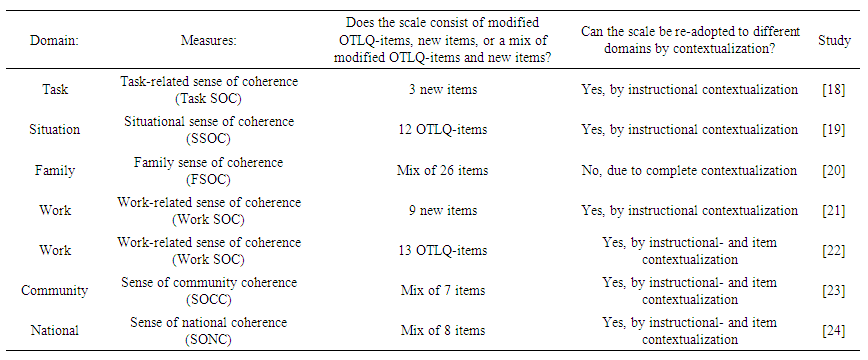

- Sense of coherence (SOC) is the core construct in Antonovsky´s salutogenic model of health [1-3]. According to the model, a person´s SOC affects her or his position on the health “disease-ease” continuum. SOC represents the extent to which a person perceives the world and her or his life as meaningful, comprehensible, and manageable. Furthermore, SOC is described as a generalized and a relatively stable way of perceiving the world and one´s life. Antonovsky [2] suggested that all people set boundaries regarding what life spheres or life domains they find important. According to Antonovsky, if a person sees no life domain to be important then there is a low probability that the person has a strong SOC. However, if a person regards some life domains to be important then how meaningful, comprehensible, and manageable they are perceived will determine the person’s SOC. Furthermore, he hypothesized that one of the ways a person with strong SOC maintains her or his view of the world and life as coherent is by being flexible about the life domains included within the boundaries. By narrowing the boundaries and disregarding some life domain(s) as not important a strong SOC can be maintained and, by broadening the boundaries to include some new life domain(s) perceived as important SOC can be strengthened. He also suggested that it is not possible to narrow the boundaries so much that one´s major activity, one´s interpersonal relations, one´s inner feelings, and the main existential themes of life are totally disregarded and that one still maintains a strong SOC. SOC is commonly measured by the Orientation to Life Questionnaire (OTLQ) [15]. Both the full (29 items) and the short (13 items) version of OTLQ have been widely used and have satisfactory psychometric properties [16]. However, the OTLQ does not take into consideration the flexibility of boundaries and Antonovsky suggested that “in the future work it would be wise to include a measure of such flexibility” ([2], p. 24). Thus, the OTLQ is a generalized or global measure of SOC, and it is impossible to know which domain(s) people have had in mind when their SOC was assessed. (For a critical discussion of the SOC-construct and it´s operationalization in terms of OTLQ, please see [17].)Scales designed to assess SOC have been differently contextualized for various domains. These scales can be broadly ordered into three different categories: (a) Antonovsky’s original scale designed to measure SOC (OTLQ), which can be contextualized in instructions and items to various domains; (b) Alternative scales developed to measure SOC, which can be contextualized in instructions and/or items to various domains; (c) Scales that are completely contextualized, or in other words, are uniquely designed to measuring SOC in a specific domain. Table 1 presents some examples of scales that measure individuals´ SOC, in terms of comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness, in different domains. It can be seen in the table, for example, that the 9-item scale, constructed by Vogt et al. [20], was contextualized in instructions to measure SOC in relation to work and that this scale can be contextualized to another domain by changing the reference in the instructions to another (e.g., school).

| Table 1. Domain-specific SOC-scales |

4. Conclusions

- In the second section of this theoretical text on the methodological issue of contextualization of scales, central topics related to contextualization were briefly reviewed and findings from empirical studies were presented which indicated that contextualization – at least for some predictors, outcomes, and domains – does improve the predictive power. In the third section, examples of contextualization of SOC for various domains were presented and four topics for future research were suggested. Many of the suggestions for future research on SOC are also applicable to other concepts. More research is also needed on the pros and cons of the three types of contextualization. It is believed that contextualization of measures is an important methodological aspect that should be considered in both research and practice.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML