-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2025; 15(2): 29-39

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20251502.01

Received: Mar. 25, 2025; Accepted: Apr. 19, 2025; Published: Apr. 22, 2025

The Conceptualization of the Term “Feeling Stressed” Among Polyvalent Nursing Students at ISPITS of Rabat-Morocco

Fouad Ktiri, Benacer Himmi, Hicham Sfar

Higher Institute of Nursing Professions and Health Techniques, Rabat, Morocco

Correspondence to: Fouad Ktiri, Higher Institute of Nursing Professions and Health Techniques, Rabat, Morocco.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Objectives: The present study examined how the polyvalent nursing students of the Higher Institute of Nursing Professions and Health Techniques (ISPITS-Rabat-Morocco) conceived the term feeling stressed”. We checked whether they were referring to a specific type of sensation (emotional, mental, physical) or two of them or all together, when they were saying they were stressed at the time they felt it. Materials and methods: A quantitative cross-sectional study was conducted among students of the three years of polyvalent nursing courses. Using a 7-Likert scale, the students were asked to assess their states of stress and their emotional, mental and physical sensations that they were experiencing before and after carrying out a mental arithmetic task. An ordinal logistic regression method was used to investigate the association between the state of stress and the 3 types of sensations. Results: 222 polyvalent nursing students out of 307 were included in the experience. Their increased perceived states of stress, after carrying out the mental task, were found to be significantly associated with the emotional distress and the mental fatigue and not with the physical tiredness. The mental sensation (mental fatigue) was found to have more effects in predicting the likelihood of feeling stressed. In addition, the lower the intensity of emotional or mental sensation, the more likely the students were to experience stress, given that one of the both sensations is held constant whatever the intensity of physical sensation. We conclude that the polyvalent nursing students refer more to mental fatigue than to emotional distress, and not to physical tiredness, when they say they felt stressed. The implications of the study are discussed.

Keywords: “Feeling stressed”, Emotional sensation, Mental sensation, Physical sensation

Cite this paper: Fouad Ktiri, Benacer Himmi, Hicham Sfar, The Conceptualization of the Term “Feeling Stressed” Among Polyvalent Nursing Students at ISPITS of Rabat-Morocco, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 15 No. 2, 2025, pp. 29-39. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20251502.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Stress phenomenonThe stress phenomenon has been studied for many decades. Many psychological models and empirical studies have been developed and carried out respectively in order to understand the stress concept and investigate its effects on physical and mental health. Some of these studies were those of Walter Cannon (Fight and Flight model: 1932) [1], Hans Selye (General Adaptation Syndrome: 1950) [2], Susan Folkmann & Richard S. Lazarus (Transactional theory of stress: 1984) [3] and Fouad Ktiri (Tri-Transactional theory of stress: 2016) [4].People and students suffering from stressThe number of people who suffer from stress has been increasing throughout the world for many years. In the modern era it is rising day by day and approximately all ages experience stress [5]. In Sweden, this number has more than doubled between 2008 and 2018 and the percentage of stress-related illnesses has also risen by 119 % between 2010 and 2015 [6]. Students are no exception. Nursing students, among others, suffer also from stress. Their level of stress, according to many studies, is high. It is due to the required complex care they give during their practicum [7]. It was also stated that nursing students are more stressed than students of other health courses [8].The term stress: use and meaning Not only there is a rise in the number of stress-related illnesses, but the term "stress" has started for many years to be widely used [9] [10] [11] and everywhere in western society as well as by researchers of social sciences and the lay people [12]. The expression “feeling stressed out” has also become familiar among individuals [13]. The vast use of the term stress is not recent. It was pointed out some decades ago (1988) that it had been used, and sometimes abused, by scientists and non-scientists [14].However, despite the wide use of the term stress in everyday language, not all people mean the same thing. It is vague and difficult to define precisely [15] and the disagreement about its meaning was indicated as well as before [16] and very recently [17]. It could refer either to subjective feelings of distress or to factors that cause them. It was also described as an ambiguous term, which means for some people excitement and challenge (good stress) or as an undesirable state of frustration, chronic fatigue (bad stress) [18]. Hans Selye was the first who used it in the late 1930s. He borrowed it from physics [14], meaning the forces or pressures that deform a material object. He used it in physiology to describe the non-specific changes that occur in the organism after it faces any demand [19], i.e. the inner feelings that result from them. For Chrousos et al. (1988), the words “stress” and “stressor” (stress factor) mean the state of threatened balance or harmony and the disturbing forces that threat this harmony respectively [14].The use of the term stress in the present studyIn the present study, the term stress refers to an unpleasant state that a person could experience after he/she faces a stressor and then says, “I am stressed” or “I feel stressed”. Nevertheless, even when referring to this definition, not all people describe the same subjective sensation or feeling. Some express being stressed at work when they are under pressure, so that effectiveness is related to stress, i.e working hard [20]. Some other people refer to “frustration, “chronic fatigue” or the “inability to cope” as undesirable negative states [21]. In a recent study (2022) the term “stressed” was used to mean a negative state that differs from reported emotional states, namely “worried”, “hesitant”, “anxious”, “frustrated”, “sad”, “reluctant”, “depressed” and “scared” [22]. Students, like anyone else, suffer from stress, and use this term particularly when their exams approach. Some of them use it to describe the Stress caused by anxiety about exam uncertainty and performance, the latter being requested by parents and teachers [23]. In a study [24], examining the impact of stress on the secondary students’ achievement motivation, the term was used to imply strain, inability or hardship. For Apriliyani, I., and Maryoto [25], who investigated the relation between stress levels and coping mechanisms in thesis writing among undergraduate nursing students, the term referred to the demands or pressure suffered by individuals to adapt to such pressures. In the present study, in order to eliminate the confusion in the term stress that is used as a subjective negative feeling, we will differentiate between physical, mental and emotional states, which could refer, in their adverse aspects, to physical, mental and emotional stresses. Some authors have also distinguished, in their study, between different types of feelings. In their Toulousaine stress scale, the authors distinguished between 4 different states of stress: physical (“I bite my nails”…), psychological (“I worry”…) psycho-physiological (“I am tired”…) and temporal (“I have difficulty organizing what I have to do”…) [26]. Classifying human stress as the purpose of their study using blood oxygen saturation experience [27], Xinyu Liu, X. et al. differentiated between emotional (psychological) and physical stress, such as nervousness and muscle tension resulting from excessive exercise respectively. The aim of the present studyIn the previous studies, the word “stress” and the term “feeling stressed” were investigated, sometimes interchangeably, in terms of causes and/or consequences. Other researchers examined them with regard to how people describe their general states when they declare stressed, such as being under pressure or depleted of their internal reserves or which combination of sensations make them generally say they feel stressed.In their study [28], interviewing employees, Gail K. and Fiona J. examined the lay representations of work stress, the occupational stress, its causes and consequences. They found that little consensus was found in how employees interpreted the concept of stress: they referred to a range of different personal, social and environmental factors when defining the term stress. The meaning of the term among children was illustrated by the findings of Kostenius, C. et al. [29] study conducted on Swedish schoolchildren who perceived stress as related to time and challenges: “being out of time” , “being in a fleeing” or “ being lifted to excel”.According to Zheng, Shuai, et al. [30], through the development of a traditional Chinese medicine questionnaire for diagnosing stress, the most commonly reported symptoms of stress (n=65 symptoms) by both women and men are “anxious or racing thoughts”, “constant worrying” and “inability to concentrate”.However, to our best knowledge, no research was conducted to precisely investigate what kind of unpleasant sensations make people constantly say they are stressed every time they experience it. Thus, by distinguishing between the 3 types of sensations (emotional, mental and physical), the aim of the present empirical study is to check whether they refer to one or two of them or all together. In other words, we will check to which of these sensations’ intensities, the intensity of their perceived state of stress is significantly associated.Due to their high stress level compared to other health courses [8] and due to their high number compared to students in other sections, the polyvalent nursing students will be used as the current study population. In addition, to have a sufficient number of participants in the present study who could feel stressed, an experimental framework will be proposed. They will undergo a mental test, which, according to previous studies, increases stress. We will also make them practice an exercise of relaxation in order to reduce it.

2. Methods and Materials

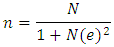

- Study design and periodThe research was conducted from May to June 2021 at the Higher Institute of Nursing Professions and Health Techniques (ISPITS) of Rabat-Morocco that offers 3-years bachelor’s degree in paramedical courses. A quantitative cross-sectional study was employed. Study population and sample sizeThe number of students studying polyvalent nursing courses in the first, second and third years at the ISPITS institute is high (N=307) compared with the other sections.Considering that some students might be absent, the selection of the participants was based on their availability (i.e. their presence in classes). A convenience non-probability sampling method was adopted.The suitable sample size calculated using the Taro Yamane formula [31] was 174.

Wheren = sample size N = population size e = the level of precision = 5%Eligibility criteriaThe inclusion criteria were that the participants had to:- have a level of education sufficient to understand how to fill a 7-likert scale and carry out a serial subtraction arithmetic;- be of any cultural, socio-economic or social status, since stress is a universal phenomenon. The polyvalent nursing students met the 2 above conditions. Materials In order to make the participants experience states of stress, we employed a mental task. It consisted of a serial subtraction test in which the participants had to decrement 1022 by 13 during 3 minutes without using a calculator. This task, known to induce a cognitive workload, has been used in previous studies and showed its stressful effect on subjects. Another task was carried out after the first one, so as the participants would not have remained stressed. It consisted of a relaxation exercise accompanied with music. During this practice, the participant sat on a chair, closed his/her eyes and, without moving, listened to soft music for 8 minutes.Assessment tool and scoring To assess the level of stress and that of the emotional, mental and physical sensations perceived by the participants before and after carrying out the mental task, we used a one-item scale. This kind of scales was used in many previous studies. Elo et al, in their research, aimed the validity of a 5-Likert single-item scale whose responses vary from “not at all” to “very much” [32]. They asked the participants to answer the question “Stress means a situation in which a person feels tense, restless, nervous or anxious or is unable to sleep at night because his/her mind is troubled all the time. Do you feel this kind of stress these days?”. Assessing the postoperative pain intensity in the post anesthesia care unit, Lee et al. [33] used an 11-point single scale whose responses varied from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain). After carrying out the mental task, the students were asked to choose the most appropriate intensity that corresponded to their perceived states. The intensities were on the 7-likert scores:Stress state: very stressed (-3), stressed (-2), little stressed (-1), not stressed (0), little relaxed (+1), relaxed (+2), very relaxed (+3)Emotional sensation: very bad (-3), bad (-2), little bad (-1), not bad (0), little happy (+1), happy (+2), very happy (+3) Mental sensation (mental fatigue): very tired (-3), tired (-2), little tired (-1), not tired (0), little rested (+1), rested (+2), very rested (+3)Physical sensation (physical fatigue): very tired (-3), tired (-2), little tired (-1), not tired (0), little rested (+1), rested (+2), very rested (+3)Mental and physical fatigues, defined as a feeling of tiredness caused by demanding cognitive activity [34] and a feeling of bodily fatigue [35] respectively, were explained to the participants and how to assess them. Likewise, for allowing them to distinguish between emotional state, mental and physical fatigue, we let them know and select one or some types of emotions that could experience when they feel stressed. The kinds of emotions they had to select from were “nervous”, “sad”, “irritated”, “disturbed”, “anxious”, “deceived”, “feared” and “other”.Many studies have indicated the affective reactions that correspond to perceived stress. In their study to investigate if perceived emotions and mental stress had negative effects on the rescuers’ performance, Sabina Hunziker et al. [36] defined negative emotions as shame, anxiety, irritation, disappointment, guilt, and desperation, and positive emotions as pride, relief, joy, pleasure, and interest. Nursing students, in the study conducted by Kristen L. Reeve et al. [37], were asked to select all feelings experienced in stressful situations, among others, worry, fear, grief, anxiety, anger, guilt, or depression.Ethical considerationsWritten approval was obtained from the Institute authorities to conduct the research. In addition, after explaining the procedure to the students, they provided an oral informed consent. They were also said they were free to participate or not.Moreover, the mental arithmetic task used in clinical tests to evoke and detect stress [38], [39], [40], poses less ethical problems than some other stressors [41]. Also, an exercise of relaxation was performed to make the participants reduce their stress.Data collectionThe data was collected in classes. For each section of the polyvalent nursing students (S2, S4 and S6) that corresponds to the first, second and the third year respectively, we asked them to perform the task and then assess their perceived states. Data on name (the 2 first letters), surname, sex, date of birth, nationality, were also collected.

Wheren = sample size N = population size e = the level of precision = 5%Eligibility criteriaThe inclusion criteria were that the participants had to:- have a level of education sufficient to understand how to fill a 7-likert scale and carry out a serial subtraction arithmetic;- be of any cultural, socio-economic or social status, since stress is a universal phenomenon. The polyvalent nursing students met the 2 above conditions. Materials In order to make the participants experience states of stress, we employed a mental task. It consisted of a serial subtraction test in which the participants had to decrement 1022 by 13 during 3 minutes without using a calculator. This task, known to induce a cognitive workload, has been used in previous studies and showed its stressful effect on subjects. Another task was carried out after the first one, so as the participants would not have remained stressed. It consisted of a relaxation exercise accompanied with music. During this practice, the participant sat on a chair, closed his/her eyes and, without moving, listened to soft music for 8 minutes.Assessment tool and scoring To assess the level of stress and that of the emotional, mental and physical sensations perceived by the participants before and after carrying out the mental task, we used a one-item scale. This kind of scales was used in many previous studies. Elo et al, in their research, aimed the validity of a 5-Likert single-item scale whose responses vary from “not at all” to “very much” [32]. They asked the participants to answer the question “Stress means a situation in which a person feels tense, restless, nervous or anxious or is unable to sleep at night because his/her mind is troubled all the time. Do you feel this kind of stress these days?”. Assessing the postoperative pain intensity in the post anesthesia care unit, Lee et al. [33] used an 11-point single scale whose responses varied from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain). After carrying out the mental task, the students were asked to choose the most appropriate intensity that corresponded to their perceived states. The intensities were on the 7-likert scores:Stress state: very stressed (-3), stressed (-2), little stressed (-1), not stressed (0), little relaxed (+1), relaxed (+2), very relaxed (+3)Emotional sensation: very bad (-3), bad (-2), little bad (-1), not bad (0), little happy (+1), happy (+2), very happy (+3) Mental sensation (mental fatigue): very tired (-3), tired (-2), little tired (-1), not tired (0), little rested (+1), rested (+2), very rested (+3)Physical sensation (physical fatigue): very tired (-3), tired (-2), little tired (-1), not tired (0), little rested (+1), rested (+2), very rested (+3)Mental and physical fatigues, defined as a feeling of tiredness caused by demanding cognitive activity [34] and a feeling of bodily fatigue [35] respectively, were explained to the participants and how to assess them. Likewise, for allowing them to distinguish between emotional state, mental and physical fatigue, we let them know and select one or some types of emotions that could experience when they feel stressed. The kinds of emotions they had to select from were “nervous”, “sad”, “irritated”, “disturbed”, “anxious”, “deceived”, “feared” and “other”.Many studies have indicated the affective reactions that correspond to perceived stress. In their study to investigate if perceived emotions and mental stress had negative effects on the rescuers’ performance, Sabina Hunziker et al. [36] defined negative emotions as shame, anxiety, irritation, disappointment, guilt, and desperation, and positive emotions as pride, relief, joy, pleasure, and interest. Nursing students, in the study conducted by Kristen L. Reeve et al. [37], were asked to select all feelings experienced in stressful situations, among others, worry, fear, grief, anxiety, anger, guilt, or depression.Ethical considerationsWritten approval was obtained from the Institute authorities to conduct the research. In addition, after explaining the procedure to the students, they provided an oral informed consent. They were also said they were free to participate or not.Moreover, the mental arithmetic task used in clinical tests to evoke and detect stress [38], [39], [40], poses less ethical problems than some other stressors [41]. Also, an exercise of relaxation was performed to make the participants reduce their stress.Data collectionThe data was collected in classes. For each section of the polyvalent nursing students (S2, S4 and S6) that corresponds to the first, second and the third year respectively, we asked them to perform the task and then assess their perceived states. Data on name (the 2 first letters), surname, sex, date of birth, nationality, were also collected.3. Data Analysis

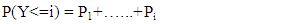

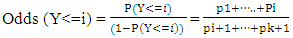

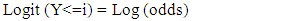

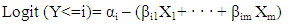

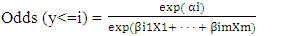

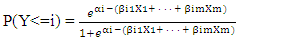

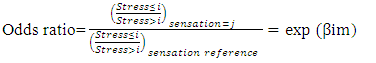

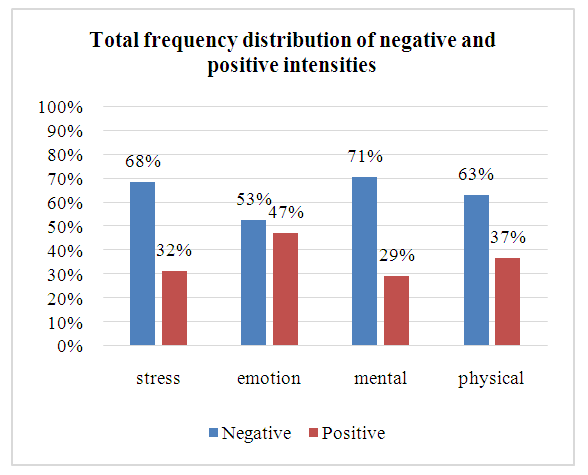

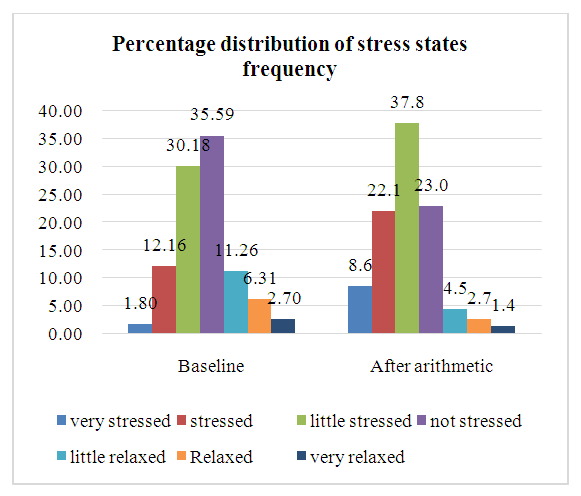

- The ordinal logistic regression model was used to investigate the relationships between the state of stress considered as a dependent variable (DV) and the 3 independent variables corresponding to emotional, mental and physical sensations. The correlations between the ordinal independent variables, using Rho spearman coefficient, were calculated to check one of the assumptions (the multicollinearity) required to perform this model.The Wilcoxon test was used to check whether the perceived states of stress intensities change between pre- and post- arithmetic task.The Taro Yamen’s formula (1973) was used to determine the minimum representative sample size.The level of significance was set at 95% for all statistical parameters (p<0.05).IBM SPSS (Version 26; IBM Corp, 2012) software was used to perform these analyses.Ordinal logistic regression is a statistical method used to model the relationships between an ordinal variable and one or more predictors (explanatory variables). The predictors may be ordinal, continuous or categorical. The ordinal logistic regression is an extension of the binary logistic regression, taking into account more than two ordered levels of the dependent variable. In this study, the number of the ordered categories of the state of stress (DV) is 7. Instead of modeling the dependent variable itself, this statistical technique models the probability of its categories. The most well-known and most frequently used approach to model ordinal outcome is the proportional odds logistic regression model (POM) [42] [43].In this model, we estimate the cumulative probabilities, rather than discrete categories, of being at or below a response-variable category versus being in categories above it. The effect of each independent variable is the same for all categories of the dependent variable. This is referred to as the parallel lines assumption. Using the logit link function, the model performs logarithmic transformations of cumulative probabilities expressing then the non-linear relationships between the IVs and the DV in a linear model. Thus, considering k+1 categories of the ordinal dependent variable Y, the cumulative probabilities of a response of Y less than or equal to a category (i) is given by:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

is the coefficient regression that corresponds to the intensity “very bad” (-3).In order to carry out the ordinal logistic regression, we checked the following assumptions: the scale of the DV, the independence-of-observations, the multicollinearity, the model fitting information and the parallel lines.

is the coefficient regression that corresponds to the intensity “very bad” (-3).In order to carry out the ordinal logistic regression, we checked the following assumptions: the scale of the DV, the independence-of-observations, the multicollinearity, the model fitting information and the parallel lines.4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Descriptive Results

4.1.1. Study Variables

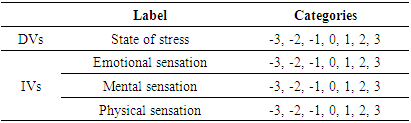

- Table 1 shows the list of the dependent (state of stress) and the independent variables’ (emotional, mental and physical sensations) categories. Their measurement was performed 2 times (at baseline and after the arithmetic task).

|

4.1.2. Comparison of Negative and Positive Intensities

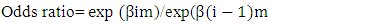

- Figure 1 illustrates that the total frequency of the negative categories (-3, -2, -1) of the DV and the IVs are higher compared to the positive categories (0, +1, +2, +3). This implies that most of the students negatively assessed their state of stress and their 3 types of sensations after they have carried the arithmetic task.

| Figure 1. The total frequency percentage of negative and positive intensities of stress, emotional, mental and physical sensations after arithmetic task |

4.1.3. Effect of the Arithmetic Test on Stress

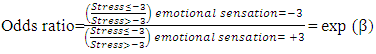

- Figure 2 shows the frequency percentage of the intensities of stress perceived by the polyvalent nursing students before and after performing the arithmetic task. The statistical analysis of the difference between pre-and post-arithmetic task shows a significant Wilcoxon test result (z=-7,213; p<0.0001). It illustrates that the percentages of the perceived negative states of stress intensities (very stressed, stressed and little stressed) and that of the positive states (not stressed, little relaxed, relaxed, and very relaxed) increase and decrease significantly respectively after performing the arithmetic test.

| Figure 2. The frequency distribution of intensities of the state of stress assessed at baseline and after arithmetic task |

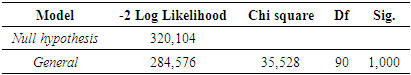

4.2. Ordinal Logistic Regression Results

4.2.1. Assumptions

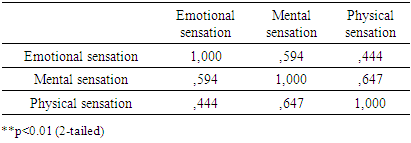

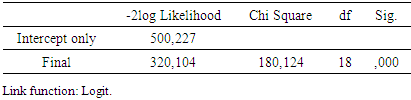

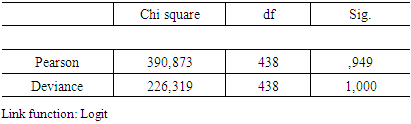

- The assumptions of applying the ordinal logistic model were met: the dependent variable (state of stress) was measured on an ordering ordinal level and had more than 2 categories. The independence of observations is satisfied as each observation came from a different polyvalent nursing student. For the test of multicollinearity, Table 2 represents the correlations between the independent variables measured after the arithmetic task. Despite the significant correlations between emotional, mental and physical sensations, none of them is highly correlated with each other (<0,650).

|

|

|

|

|

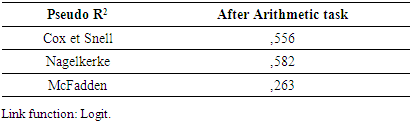

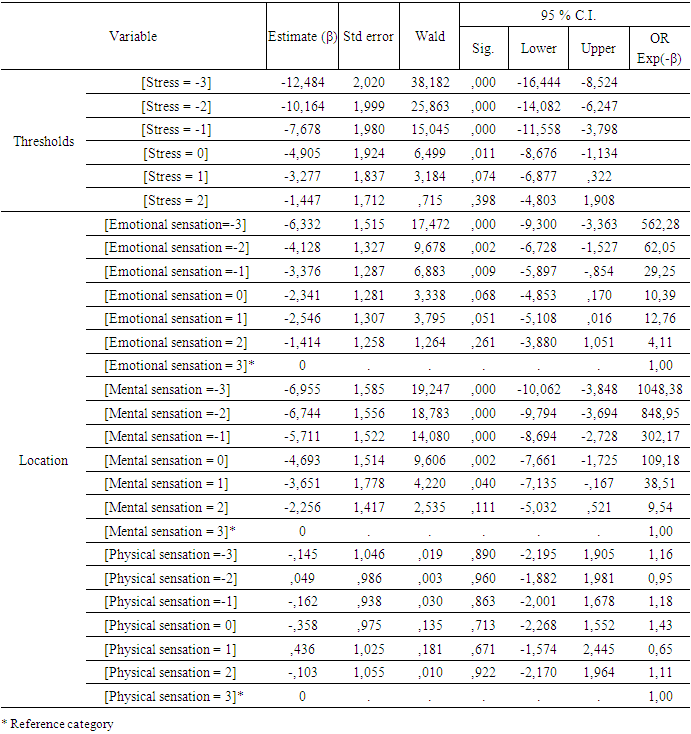

4.2.2. Outcomes

- Table 7 shows the outcomes of the ordinal logistic regression used to model the relationships between the intensities of the perceived states of stress and the intensities of the different sensations (emotional, mental and physical) assessed after performing the arithmetic task. The values of the regression coefficients (the estimates) and the corresponding standard errors, Wald’s values and their significance’s values and odds ratio are presented. The intensity (+3) of the state of stress and of the states of the 3 types of sensations was set as a reference point. Since the estimates are negative, the odds of being in lower categories versus higher categories were calculated on the base of (- β).

|

5. Implications

- From the findings of the present study, the implications that could be deduced are: the institute’s teachers and officials who deal with stressed polyvalent nursing students, have to take into account that these latter are more likely to suffer from emotional distress and/or mental fatigue. This is especially during the exam’s preparation period, a cognitive demanding work.

6. Limitations of the Study

- A large percentage (72%) of the target’s population (polyvalent nursing students) participated in the present study. However, the sampling method used, due to the expected absence of the nursing students, was non-probabilistic. The findings were obtained using a specific population and an arithmetic test that had more effects on the mental sensation and no effect on the physical one. The results could then not be generalized.

7. Conclusions

- The purpose of the present study was to investigate if emotional distress, mental fatigue and physical tiredness could affect the feeling of the state of stress of the polyvalent nursing students at the ISPITS institute of Rabat-Morocco. The approach, distinguishing between the 3 types of sensations, was to our best knowledge not used in previous studies.The students underwent a serial subtraction test to increase their stress. After performing the mental task, their increased perceived states of stress, in their intensities (“very stressed”, “stressed”, “little stressed”), were found to be significantly associated to mental fatigue and emotional distress and not to physical tiredness. In addition, the lower the intensity of emotional or mental sensation, the more likely the students are to experience stress. Moreover, contrary to emotional distress where only the category “very bad:-3” was highly significantly associated, all negative intensities of the mental fatigue (“little tired”, “tired” and “very tired” were highly associated (p<0.0001) with the perceived states of stress and its regression coefficients effects are higher than the first one.We conclude that when a polyvalent nursing student of the ISPITS institute, after performing a serial subtractions test, says “I am stressed” or “I feel stressed”, he/she refers to emotional negative feelings and mental fatigue, with this latter having more effects than the first one.

8. Recommendations

- New other studies, targeting large populations and using other tests to elicit either emotional or physical sensations in addition to mental one, could investigate if the participants will always refer to the same sensations when they declare stressed or even relaxed. A new other study to investigate the relationships between mental fatigue and emotional distress is highly recommended so as to find out if people refer to only one sensation that causes the other ones to be also linked to the stress feeling.Future studies could then allow us to find out if most people constantly refer to the same sensations when they say “I feel stressed”. This would remove the confusion generated by the term «feeling stressed».

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I would like to thank the ISPITS institute administration of Rabat-Morocco for allowing us to perform this experimentation. Our great thanks also to the polyvalent nursing department and its staff, including the professors, for permitting us access to the classrooms and doing the research.Our sincere appreciation to the polyvalent nursing students of the 2020-21 academic year for their availability to participate in the study.Our thanks are also expressed to all those who provided us with scientific knowledge, support and encouragement, including professors and friends.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML