-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2025; 15(1): 12-20

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20251501.02

Received: Nov. 26, 2024; Accepted: Jan. 3, 2025; Published: Feb. 26, 2025

Treatment-Seeking and Treatment Decision-Making Behaviors in a Culturally Changing Kharwar Adivasi Community

Awasthi P.1, Mukherjee M.2, Mishra R. C.1

1Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India

2Department of Psychology, School of Humanities, K R Mangalam University, Gurgaon, Haryana, India

Correspondence to: Awasthi P., Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The study examines the treatment-seeking, treatment decision-making, and health outcomes in a culturally changing Kharwar Adivasi community (N= 450) living in the Naugarh region of Chandauli district in Uttar Pradesh. It focuses on common health problems of the Kharwars, including jaundice, pneumonia, diarrhea, eczema, and malaria, which affect their day-to-day activities. The sample included males and females aged between 21 to 65 years. For treatment-seeking behavior, the t-test revealed a significant difference between male and female groups only for ‘folk healing’, with women resorting to ‘folk healing’ more than men. No significant differences were observed between male and female groups for ‘defensive avoidance’, but females displayed more significant ‘decisional conflict’ in making treatment decisions than males. For health outcomes, findings revealed that compared to males, females scored significantly higher on pain and severity measures. Stepwise Multiple Regression Analyses revealed contact acculturation as the most robust predictor of the variations in treatment-seeking, treatment decision-making, and health outcomes. Findings are discussed in the light of the sociocultural context of the Kharwar community, and their implications in formulating interventions for the health problems of the Kharwar people are pointed out.

Keywords: Acculturation, Health Outcomes, Treatment Decision-Making, Treatment-Seeking Behaviors

Cite this paper: Awasthi P., Mukherjee M., Mishra R. C., Treatment-Seeking and Treatment Decision-Making Behaviors in a Culturally Changing Kharwar Adivasi Community, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2025, pp. 12-20. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20251501.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- For several years, much has been explored regarding the education and health of the Adivasi people of India, who constitute one of the weaker sections of Indian society. They are distributed among around 461 communities and make up about 8.6% of India's population [1]. The term 'Adivasi' refers to a group of Indigenous people who share a common territory and culture [2]. Distinct cultural groups exist, each following their own beliefs, rituals, taboos, and cultural traditions, as well as social, economic, and political practices [3]. This paper examines the treatment-seeking and decision-making behaviors of an Adivasi community residing in remote villages of Chandauli district, Uttar Pradesh, India. In the past decades, various developmental programs have caused physical and socio-cultural changes in the villages of this region. Education, urbanization, and wage employment have played a significant role in shaping the current context. The lifestyle of Adivasi people with access to elements of socio-cultural change is significantly different from those still bound to their traditional culture. Research on socio-cultural change can be classified into two major traditions. The first one is the 'modernization' tradition [4] which views socio-cultural change as a transition from traditional to modern. The second tradition is ethnic group relations, which focuses on changes due to contact with other cultural groups. Acculturation refers to the process of change that occurs when two cultural groups have continuous contact over a period of time [5,6]. This change can be subjective, involving alterations in values, perceptions, and attitudes and objective changes in lifestyle and cultural elements such as language, clothing, diet, and religious practices. Contact acculturation can be considered an objective indicator of the degree of cultural exchange and change. Traditional culture is often the focus of developmental programs, including healthcare-related ones. However, these programs may require changes that conflict with Adivasi behaviors [7]. The current approach to healthcare assumes universal diseases and treatments, ignoring the role of sociocultural embedding in shaping beliefs and behaviors [8]. Developing appropriate health behaviors and maintaining them is crucial for individual health. However, the community in which individuals are embedded also plays a vital role [3]. For a long time, Adivasi communities have developed their healing systems and some rudimentary knowledge base of cure, including the judgment of illness. Both traditional and Indigenous treatment practices are used to cure the sick either together or separately [9,10]. Advanced directives that promote health have not been successful partly because they reflect the culture and beliefs of socioeconomically and educationally empowered nations. Neglecting the needs and socio-cultural concerns of tribes during the development of health directives may lead to the rejection of these directives [11,12]. Health should be viewed within a cultural context, as emphasized by researchers [13,14,15]. Psychosocial and cultural factors play an essential role in health and illness, from promoting wellness to causing chronic diseases [17,18]. Various studies have shown that individuals' health beliefs, behavior, and other aspects of illness prevention, such as regular check-ups, immunization, and screening tests to detect diseases, are influenced by their socio-cultural, religious, and economic backgrounds. This is because these factors shape their knowledge, habits, health beliefs, and behaviors [19,20,21,22,23,24]. In recent years, few studies have been on the health, education, and development-related issues that affect the Kharwar Adivasi communities living in the bordering region of Varanasi. Some of the serious health problems prevalent in the area include diarrhea, fever, child mortality, conjunctivitis, arthritis, pneumonia, malaria, jaundice, and skin diseases. As highlighted in various studies, these issues affect a significant portion of the population [20,25]. According to field surveys conducted in Kharwar villages, Primary Health Centers (PHCs) have failed to educate and motivate people to adopt appropriate health behaviors. This highlights the need for changes in the way the relationship between health service providers and seekers is managed. The problem of the relationship between PHCs and rural communities has been previously addressed in other studies [7,25,26,27,28]. However, very little work has been done assessing, comparing, and linking treatment-related behaviors (treatment-seeking, treatment decision-making), demographics (gender, age, education, affluence), and contact acculturation of people of the Kharwar community undergoing change. After reviewing the literature related to the topic of study, it is evident that two major sets of factors need to be considered when understanding people's treatment behaviors. These factors are contact acculturation and demographic factors. Based on these factors, the present study proposes the following objectives. It is important to note that this study is exploratory in nature and does not propose specific hypotheses.Objectives1. To study the sociocultural and demographic factors (i.e., age, education, affluence, and contact acculturation), treatment-seeking (i.e., clinical care, folk-healing), treatment decision-making (i.e., decisional conflicts, defensive avoidance), and health outcomes (i.e., experience of pain, hope, and severity of illness) of male and female groups.2. To explore the relationship of sociocultural and demographic factors (i.e., gender, age, education, affluence, and contact acculturation) with treatment-seeking, treatment decision-making behaviors, and health outcomes.3. To explore the relative contribution of socio-cultural and demographic factors in predicting treatment-seeking behaviors, treatment decision-making behaviors, and health outcomes.

2. Method

- SampleThe study was conducted in the Naugarh Block of Chandauli district in Uttar Pradesh, which included 20 villages. The sample consisted of 450 Kharwar individuals between 21 and 65 years of age. From each village, 24 participants were randomly selected, out of which 12 were males and 12 were females. The study included a stratified random sampling procedure for selecting participants. The selection process took into account age, educational experience, affluence, contact acculturation, along with treatment-seeking behaviors, treatment decision-making, and health outcomes related to specific health problems such as jaundice, pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, and eczema. The study focused solely on socio-demographic factors related to treatment behaviors, such as treatment-seeking and decision-making. Therefore, all procedures used were non-invasive and non-intrusive, both physically and psychologically. The methods employed in the study were approved by the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR) and the Department of Psychology, F.S.S., Banaras Hindu University, India. Only those who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study and provided their consent were included in the sample. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses and were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any negative consequences.The Field Setting The Naugarh Block covers approximately an area of 211 sq. km. Out of this area, 65% is covered with forests. The Kharwar people of this region live as a settled agricultural community, with a "forest-based" economy being a significant part of their livelihood. They engage in rudimentary agriculture, cattle rearing, and small trades. The agricultural yield is sufficient to feed their families for three to four months, but they depend mainly on forest resources for the rest of the year. Due to economic pressures, the younger generation is moving out of villages to find work, resulting in noticeable changes in some families, while the majority continue to live a traditional life. The status of education and health in the community is relatively poor. There is a lack of primary schools to cater for the children. Although a few NGOs have started programs for primary education and health care in some villages in the last few decades, the facilities are inadequate to serve the needs of the people. In addition, drinking water is scarce in the Naugarh area. A decade ago, the inhabitants struggled a lot for drinking water during the summer. Although hand pumps have been installed in most villages in recent years, due to a lack of proper maintenance, they often do not work properly, which forces people to depend on natural water resources. This is a major cause of diarrhea and other health issues among people even today. Field observations of people's health behavior [27,28] have shown that when people first become ill, they generally wait to see if the illness will go away on its own. Many people in the region believe that disease is caused by the accumulation of toxins in the body for various reasons. If the illness persists, they may consult with a local baiga (priest) to determine which type of puja (worship) should be performed and which god should be appeased. Traditional healers are also consulted, as they know the medicinal properties of herbs, roots, and seeds. It is only in the later stages of the disease, when natural remedies have failed, doctors are consulted. However, medical services are scarce in the region, and people may have to travel 10-20 kilometers on foot or by bicycle to find a doctor. The nearest Community Health Centre is in Naugarh and is often the last resort for those seeking medical attention. There seems to be a shift towards the younger generation preferring allopathic medicine over the older generation's practices. ToolsPersonal Biographical Schedule It comprised sociocultural information such as their gender, age, education, and affluence (income and living standard).Contact-Acculturation ScaleThis scale was used to measure the degree of change in the lives of Adivasi people due to their contact with the outside world [2]. The scale consists of 14 items on various contact indices, such as knowledge of English and other languages, ownership of people, dressing, means of livelihood, use of technology, travel experience, and exposure to movies. The participants are rated on each of these indices on 0–4 point scales (1 item), 0–3 point scales (6 items), and 0-2 point scales (7 items). The scores are added up to derive the index of contact acculturation which ranges from 0-36. Treatment-Seeking Behavior Measure This measure was developed to understand the treatment-seeking behaviors of people during illness [26]. Participants were asked where they would go when confronted with an illness. The measure consists of eight items that assess the degree to which the illness is considered treatable by clinical care (4 items) and folk healing (4 items). The participants rated each item on a 5-point scale (“not at all” = 1, “very much” = 5). The scores on each domain ranged from 4 to 20. The test-retest reliability of the measure ranged between .67 and .75.Treatment Decision-Making MeasureThis measure consists of 16 items that intend to understand the decision-making process of individuals related to treatment [26]. Eight items are related to decisional conflict (e.g., keeping oneself away from taking treatment decisions, hesitating a lot before making treatment). Eight items are related to defensive avoidance (e.g., giving priority to the suggestions given by the exorcist of the village for the treatment purpose, and the final decision of the treatment is made by the elders and experienced people of the village). The participants were asked to rate each item on a five-point scale (“very little” = 1, “very much” = 5). The scores of each domain ranged from 8-40. The test-retest reliability of this measure ranged from .65 to .74.Health Outcomes MeasureThis measures the outcomes of illness in terms of the subject’s perception of pain, hope, and severity of the illness [26]. The scale consists of 12 items (4 items for each domain of pain, hope, and severity) that were rated on a 5-point scale (“not at all” = 1, “very much” = 5). The scores on each domain ranged from 4 to 20. The internal consistency values for pain, hope, and severity were .80, .63, and .70, respectively.

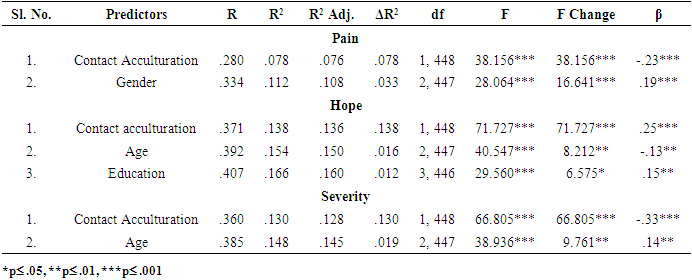

3. Results

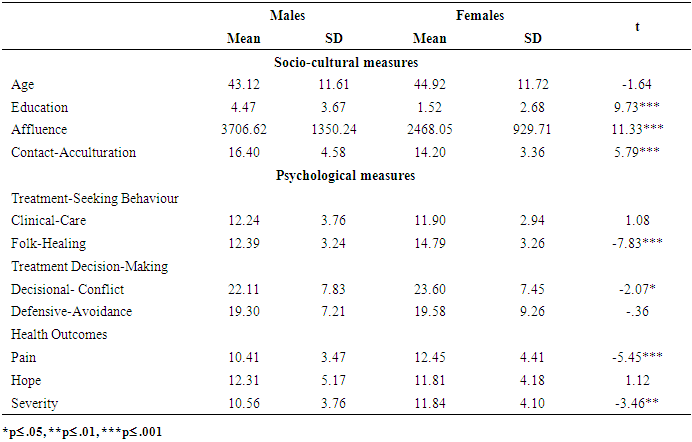

- Data were analyzed using mean, SD, t-ratio, correlation, and multiple regression analysis. Table 1 presents the mean scores for the men's and women's groups on socio-cultural measures and psychological measures related to treatment.

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

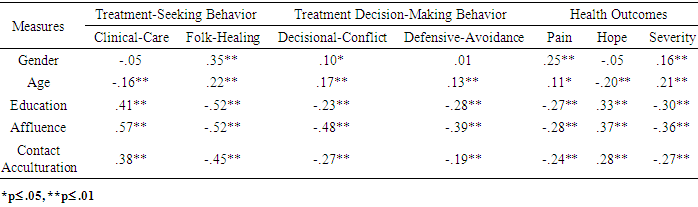

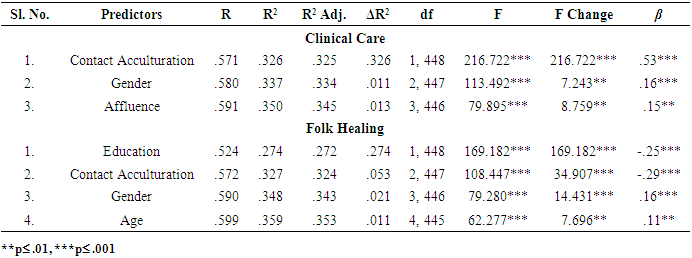

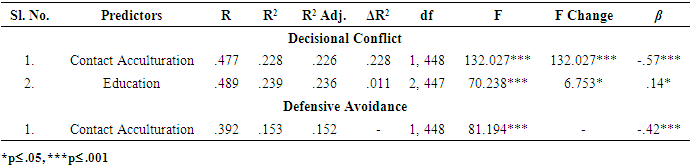

- The discussion raises the two aspects of health care in the Kharwar community: (a) sociocultural features and treatment-related psychological features of Kharwars, and (b) the role of sociocultural factors in treatment-seeking and treatment decision-making behaviors and health outcomes of Kharwars.Socio-Cultural Features and Treatment-related Psychological Features of KharwarsThe findings broadly revealed that males tended to show greater educational experience, affluence, and acculturation than females. The influence of mainstream society has entered the lives of rural Adivasi people due to the execution of tribal development and welfare schemes. The effect of acculturative influence is evident in the male group. Looking at the findings, it seems that females are not able to reap the benefits of this. Research suggests that females acculturate more slowly than males and preserve traditional roles to a greater extent [30]. The traditional roles require females to engage in household chores and child-rearing. However, females’ roles in Kharwar communities are diverse as they manage household chores, child upbringing, agricultural activities, and selling produce [25]. Further, rural Adivasi females have lesser access to health care, education, nutrition, and other valuable resources as compared to males [29]. Consequently, they become more prone to stress and hardships than males and may not benefit equally from the welfare schemes. The findings also indicate that females preferred folk healing more than their male counterparts, though both groups have shown similar preferences for clinical care. Folk healing and clinical care co-exist in the Kharwars community. Following the launch of numerous health initiatives such as POSHAN Abhiyaan, Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram, Janani Suraksha Yojana, National Rural Health Mission, and National Health Policy of 2017, modern medicinal facilities have reached rural belts. However, change in the way of life has not been felt so distinctly; mainly, the relatively isolated and traditional groups have been less affected by these programs than the more acculturated groups. Several studies in the Kharwar community indicated that traditional healthcare systems, such as consulting healers or vaidyas, were more commonly used than visiting a doctor [25,27,28]. The elderly members of the community relied more on healers, while the younger generation preferred vaidyas (Ayurvedic practitioners). Doctors' unavailability and high cost are the primary reasons behind this trend. Therefore, even now, there is a preference to keep both the folk-healing traditions of their own culture along with the clinical care that has reached their community through outside influences. The study suggests that folk medicinal systems should be acknowledged as they offer accessible healthcare options for people living in rural areas who may not have access to health professionals. Although traditional medicinal systems such as Ayurveda, Unani, and Siddha have been officially recognized as national healthcare components by the Indian Medical Council Act, indigenous folk healing systems are still largely neglected [30]. It is important to note that while folk healing can be beneficial, it is crucial to maintain its herbal medicinal values and avoid the harmful effects of superstitions and exorcism. Intervention programs may play a vital role in emphasizing these points.Role of Socio-Cultural Features in Treatment-Seeking, Treatment Decision-Making, and Health Outcomes of KharwarsAmong the five socio-cultural and demographic variables examined in the study, contact acculturation greatly accounted for greater clinical care and hope, facilitated treatment decision-making, and reduced folk-healing practices and perception of pain and severity of illness. Thus, it may be said that contact acculturation has created a positive impact on the health of Kharwars. More acculturated people generally have greater inherent trust in clinical care; they prefer to access institutions offering clinical care, which reduces conflicts related to treatment decision-making [31,32]. It is possible that they have a better understanding of the Adivasi welfare initiatives, can avail healthcare facilities more easily, have better knowledge to navigate the healthcare system, and face fewer psycho-social or cultural obstacles regarding healthcare education and responsibilities. Also, contact acculturation may promote a scientific approach to treatment-seeking and reduce conflicts and avoidance in decision-making, leading to more positive illness outcomes.The next significant role is played by education. In this study, education played a significant role in reducing folk-healing practices, which are associated with superstitions and anecdotal evidence. Education equips individuals with knowledge about the human body, diseases, and side effects associated with specific folk remedies. As educated people begin to integrate with the majority culture; they may become less likely to use folk healing as it may not align with their values or beliefs. Further, educational experience also increased hopes of recovery from illness. As people begin to understand the underlying causal factors for their diseases and the benefits of medicines, they may become more hopeful of the cure. However, a unique finding of this study is that greater education experience increased decisional conflicts. It seems that as people gain more educational experience, they tend to tilt toward modern healthcare facilities. However, due to the lack of availability of doctors in remote villages, they are compelled to visit the local healers, which might lead to a decisional conflict between beliefs and available facilities. Another plausible explanation for this finding may be that educational experience increases a sense of independence and may prompt one to make decisions on a personal level. However, in a predominantly collectivistic society, where family, relatives, and neighbors are often approached to seek guidance, trying to make decisions independently may give rise to conflicts. Nevertheless, the average educational experience of the sample is still very poor, which creates the need to conduct more studies before drawing conclusions. Next, the role of gender was significant in this study. Females sought greater clinical care and folk-healing approaches than men. They also experienced greater pain due to illness. The greater tendency of women to seek treatment, be it clinical care or folk healing, may be partly explained by the social roles of males and females. Due to the societal expectations around masculinity and the ‘stronger gender’ stereotype, males may become less likely to seek medical care [33,34]. Another study [35] found that females contacted their primary care physician more frequently than males for both physical and psychological health issues. This finding was true regardless of their age and educational experience. Additionally, females were more likely to report unmet healthcare needs, meaning that even when they were seeking care, they were not receiving it. This finding resonates with the current findings that females experienced more pain despite seeking treatment. Increasing age led to a greater preference for folk healing and experience of greater severity of illness. At the same time, older adults had less hope of recovery. A study examined the role of the patient’s age in the treatment selected, the factors influencing this selection, and the perceived quality of life [36]. Findings indicated that younger patients, even when diagnosed with localized diseases, were more likely to prefer clinical care, while older patients preferred the least disruptive treatment and chose treatments that enhanced their well-being. These findings suggest that despite the sociocultural changes, folk-healing systems coexist due to people’s belief in the wisdom, experience, and remedies of local healers. Since older adults face greater difficulties in making treatment decisions, healthcare professionals may intervene to help them view their illness as manageable, even in old age. specific health education programs may help improve their treatment decision-making and positive health outcomes.It is interesting to note that affluence contributed significantly only to clinical care, i.e., more affluent people had a greater tendency to seek clinical care. Affluence, such as income, education, employment, and living standards of people, strongly interact to influence health [37]. Having a higher level of wealth can enhance an individual's capability to bear the expenses of modern medical treatment. The affluent section of society may have better accessibility to nearby hospitals as they can afford private transport services. There exists a close association between the economic status of an individual and their health. People with low incomes generally face a lack of essential resources such as nutritious food, safe drinking water, adequate housing, and decent working conditions, which can lead to poor health outcomes. Poverty can also lead to financial distress and life stress, which can have severe negative impacts on an individual's health over time [38,39].

5. Limitations

- Despite the interesting findings of the study, there are some limitations. Local cultural contexts and community conceptions of health, including health beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors, need to be included in Indigenous health research. Further, in a closely-knit Adivasi community, social support extends from family, neighborhood, and friends to the community as well. Thus, the role of social support in treatment-seeking behaviors, treatment decision-making, and health outcomes may be focused on future research.In the present study, the age range of participants was wide (i.e., 21 to 65 years), and there is a need to work with young, adult, and old age groups to develop age-specific psychological profiles focusing on treatment-seeking behaviors and treatment decision-making. Next, it is worth noting that the average educational experience of the present sample was less than four years (Table 1). Therefore, a more meaningful way to understand the role of education would be to include Kharwars with more than 10 to 12 years of educational experience. Further, a culturally competent psycho-educational program focusing on the issues of treatment-seeking behaviors and treatment decision-making may be carried out. It seems that for the Adivasi communities, whether they are patients or healers, giving psycho-educational intervention will prove to be beneficial for improving their healthcare attitudes and behaviors.

6. Conclusions

- The present study reveals a remarkable connection between contact acculturation, education, and the treatment behaviors of the Kharwars. Increased contact acculturation and educational experiences lead to a greater inclination towards seeking clinical care, reduced conflicts in treatment decision-making, and improved health outcomes. Understanding the sociocultural context of the Kharwars is crucial for culturally competent healthcare delivery. It is essential to acknowledge the value of traditional knowledge and skills in herbal medicine that have been passed down through generations. Folk medicinal systems that avoid superstitions and exorcism can serve as a viable healthcare option until individuals can access professional healthcare services. Ultimately, the goal should be to coexist by preserving indigenous heritage and encouraging modern healthcare systems.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Purnima Awasthi has received financial assistance under the ICSSR Scheme of Travel Grant for attending Seminars/conferences abroad. She presented the paper at the European Congress of Psychology 2023, held at Brighton Centre, Brighton, United Kingdom, from 3 to 6 July 2023. This article is partly an outcome of the Research Project sponsored by ICSSR. However, the responsibility for the facts stated, opinions expressed, and conclusions drawn is entirely that of the author.

Statements and Declarations

- The corresponding author states on behalf of all authors that there is no conflict of interest. Further, the work is original, and the manuscript has not been submitted anywhere else for consideration.The study was approved by the Indian Council of Social Science Research, Ministry of Human Resource Development, New Delhi (Project Code No. M-28-07), and the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, which also approved all ethical considerations.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML