-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2024; 14(1): 15-43

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20241401.02

Received: Jun. 15, 2024; Accepted: Jul. 3, 2024; Published: Jul. 10, 2024

“They are Just LGBTQ People and Nothing Else!” Theorizing and Measuring the “Perceived Inclusion of an Outgroup Members within Individuals’ Ingroups” (PIOMI) to Evaluate Inclusive Social Tolerance in the Multiple Identities Perspective

Monique Pélagie Tsogo À Bebouraka1, Achille Vicky Dzuetso Mouafo2, Sylvestre Nzeuta Lontio3, Gustave Adolphe Messanga3

1University of Yaoundé I, Department of Psychology, Yaoundé, Cameroon

2University of Maroua, Department of Philosophy and Psychology, Maroua, Cameroon

3University of Dschang, Department of Philosophy-Psychology-Sociology, Dschang, Cameroon

Correspondence to: Gustave Adolphe Messanga, University of Dschang, Department of Philosophy-Psychology-Sociology, Dschang, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Due to the shortcomings of their methodological procedures, do the theoretical models dedicated to the analysis of the predictive effect of identity plurality on social tolerance not in reality explain this tolerance by identity singularity rather than by identity plurality as they claim? This is the paradox that emerges from a critical analysis of the literature on multiple identities in general and Social Identity Complexity (SIC) in particular. To address this limitation, we propose the concept of “Perceived Inclusion of an Outgroup Members within individuals’ Ingroups” (PIOMI), which examines the inclusive tolerance of X outgroup in individuals’ ingroups. To measure it, this study constructs and validates the Degree of PIOMI (DPIOMI) scale, a tool which assesses the degree of this inclusive tolerance. This tool is applied to the social inclusion of LGBTQ people in the Cameroonian highly heteronormative context, which is characterized by the criminalization of homosexuality and violence against LGBTQ people. Two samples of heterosexual Cameroonian students (N=666; 335 men, 331 women) made it possible to validate this tool. The exploratory results (N1=200; 103 men, 97 women) summarize the structure of the DPIOMI scale into 3 reliable factors (Perceived Inclusive Enumeration (PIE), Perceived Inclusive Similarity (PIS) and Perceived Inclusion Core (PIC)). The confirmatory results (N2=466; 235 men, 231 women) report an adequate structural fit of this tri-factorial structure to the data. The invariance test indicates the same understanding of the content of each item of the scale, regardless of the gender of the respondents. The construct, discriminant and predictive validities of this scale are satisfactory. With regard specifically to predictive validity, the data collected reveal that the low inclusive tolerance of LGBTQ people in the participants’ ingroups is explained by their homo-negative cognitions, affects and behaviors.

Keywords: Identity singularity, Identity plurality, SIC, PIOMI, DPIOMI, LGBTQ

Cite this paper: Monique Pélagie Tsogo À Bebouraka, Achille Vicky Dzuetso Mouafo, Sylvestre Nzeuta Lontio, Gustave Adolphe Messanga, “They are Just LGBTQ People and Nothing Else!” Theorizing and Measuring the “Perceived Inclusion of an Outgroup Members within Individuals’ Ingroups” (PIOMI) to Evaluate Inclusive Social Tolerance in the Multiple Identities Perspective, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2024, pp. 15-43. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20241401.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The multiple identities perspective constitutes a response to the criticisms raised against Social Identity Theory (SIT; Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and Self-Categorization Theory (SCT; Turner et al., 1987), on the insufficiency of identity singularity to account for the reality of individuals’ group affiliations. Indeed, these theories analyze intergroup relations through the prism of identity singularity (Grigoryan et al., 2020; Ramarajan, 2014; van Dommelen, 2014), while in fact, individuals are at the crossroads of several social categories (Crisp & Hewestone, 2007). To address this gap, scholarly interest in multiple social categorization has grown, leading to a thriving and diverse theorizing, ranging from cross-categorization to Social Identity Inclusiveness and Structure (Reimer et al., 2022). van Dommelen (2014) lists and classifies the theoretical models designed in this area, according to whether they are unidimensional (Gordon, 1964), bidimensional (Berry, 1997), intersectional (Benet-Martínez et al., 2002; Benet-Martínez & Haritatos, 2005), or hierarchies of inclusiveness (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000; Gaertner et al., 1993). Cross-cutting conceptualizations, such as Social Identity Complexity (SIC; Roccas & Brewer, 2002), Social Identity Inclusiveness (SII; van Dommelen, 2014) and Social Identity Structure (SIS; van Dommelen, 2014), which are located at the crossroads of transversal categorization and identity complexity, are the most recent theoretical models in the wake of cross-categorization. Despite the advances in knowledge that these theoretical models have made in the field of multiple identities, they present shortcomings noted in particular in the excellent literature review carried out by van Dommelen (2014). The present study, which positions itself within the framework of transversal categorization and complexity, is specifically interested in models that fit into this theoretical perspective.

1.1. Research on Identity Complexity and Its Limits

- The paradigm of transversal categorization (see Deschamps & Doise, 1978) has inspired research on identity complexity. It proposes that categorization processes can simultaneously be inhibited in favor of a reduction in the ingroup/outgroup differential importance in crossed intergroup contexts (Deschamps, 1977; Roccas & Brewer, 2002). Following this logic, the crossing of two orthogonal categories produces four different groups: a double ingroup, a double outgroup and two crossed categories where individuals find themselves at the intersection of a dimension (Deschamps & Doise, 1978). This perspective is at work in SIC, which proposes that although individuals identify with multiple groups, the number of groups with which they identify is less important than how these different identities are subjectively combined to determine the overall inclusive nature of ingroup membership (Brewer, 2010). In both conceptualization and measurement, SIC takes into account the interrelationships between multiple identities of the perceiver, to the extent that these can impact attitudes towards outgroup members (Brewer & Pierce, 2005; Roccas & Brewer, 2002). SIC scores are interpreted on a continuum, depending on whether the perceiver’s multiple memberships strongly overlap (simple structure corresponding to low SIC) or are highly differentiated (complex structure corresponding to high SIC; Roccas et al., 2021). The criticism formulated by van Dommelen (2014), both regarding transversal categorization and SIC, is that these models do not take into account perceiver’s degree of identification with the groups on which the categorical pairings are nevertheless based, especially when these are perceived as not overlapping. To remedy this, he proposes SII, which is located at the intersection of the psycho-cognitive awareness of non-convergent category pairings and the perceiver’s identification with these non-overlapping categories. Specifically, the SII refers to the way in which perceiver inclusively or exclusively defines its ingroup based on the combination of its multiple transversal memberships (van Dommelen, 2014). Thus, an individual with a high SII is less rigid in his criteria for identifying with others as “one of us”, unlike an individual with a low SII. However, the link between high SII and permeable identification criteria depends on the rules of inclusiveness that the perceiver himself applies to the pairings of these multiple social identities over time (van Dommelen, 2014). As for the SIS, it is a qualitative construct which determines the structure corresponding to the ingroup constructed by the perceiver on a continuum (intersection, dominance, fusion and egalitarianism); given that SII does not necessarily capture this content (van Dommelen, 2014). In agreement with van Dommelen (2014), the criticism that can generally be made of research on cross-categorization relates to the fact that it focused more on the multiple affiliations of a target person, in order to evaluate their impact on social impressions; consequently, neglecting the processes that underlie perceiver’s own ingroup representations in conditions of transversal membership (see Hewstone et al., 1993; Migdal et al., 1998 for illustrations). In addition, they have common methodological flaws on which the present study wishes to dwell, relying mainly on SIC, as it was theorized and measured by Roccas and Brewer (2002).

1.2. The Methodological Shortcomings of Research on Social Identity Complexity

- For the present research, SIC presents some shortcomings relating in particular to the methodological procedures allowing it to be evaluated and linked to intergroup positivity.First, SIC does not take into account the socio-identity plurality of the members of the perceived group (the outgroup). In fact, it simply measures the degree of perceived overlap within individuals’ ingroups, by activating them through the Group Elicitation Questionnaire (GEQ; Miller et al., 2009), to then evaluate individuals’ attitude towards an outgroup of which only one of the identity markers is made salient (the black race for example; Brewer & Pierce, 2005; Roccas & Brewer, 2002). Indeed, SIC is conceived as an independent variable predicting tolerance, generally assessed by an external measure such as the Bogardus (1925) social distance scale (see Brewer & Pierce, 2005; Roccas & Brewer, 2002). This procedure could prove problematic due to the potential disconnection between SIC and the tolerance measure, due to the neutralization of the socio-identity plurality of the perceived group due to the activation of only one of its members’ identity markers at the level of the tolerance measurement. However, a member of the outgroup (a black person for example) can have a socio-identity plurality (socio-professional, religious or political groups) which is deployed within the same ingroups as those of a perceiving individual (a white person) (Brewer, 2010; Roccas & Brewer, 2002). From this perspective, it was expected that SIC would simultaneously capture the multiple identities of the perceived (outgroup member) and the perceiver (ingroup member). But this is not the case. Secondly, and paradoxically, SIC also neutralizes the identity plurality of the perceiver, although activated with the GEQ and maintained constant with its tools (the Overlap Complexity (OC) and Similarity Complexity (SC) measures). However, by studying tolerance towards an outgroup, SIC only activates one of the perceiver’s identity markers (the black race for example; Brewer & Pierce, 2005; Roccas & Brewer, 2002). However, the activation of a single identity marker of the outgroup is likely to induce the activation of the corresponding identity marker within the ingroup (the white race for example), since the notions of ingroup and outgroup are always located in the perspective of specific identity markers and therefore escape, as a result, the social identity plurality (see Grigoryan et al., 2020 for an analysis of multiple categorization). As an illustration, in a research protocol involving SIC and ingroup threat, to evaluate the impact of a high threat situation on SIC, Roccas and Brewer (2002) report that a high threat situation generated from the activation of an identity characteristic of the outgroup has no significant effect on non-threatened categorical pairings, compared to threatened category pairings. This means that the threat posed to one identity marker does not impact other non-threatened identity markers. In other words, despite the reality of identity plurality, singular identities retain their importance, since they are the ones that are activated in the situations experienced by individuals and it is by referring to them that they react. The results of this research can be extrapolated to measures of tolerance towards members of the outgroup, since the activation of the identity unidimensionality of the outgroup (race for example) is likely to activate the identity unidimensionality of the ingroup (the race also). There could therefore be a sort of singularization of identity plurality activated by the GEQ. Consequently, we can estimate that the paradox of the SIC is that while criticizing the salient identity singularity in the social identity theory, it itself only measures the said singularity in its evaluation of tolerance towards the outgroup, since it makes a single characteristic of the said group salient. Third, SIC is an independent variable linked to social tolerance (Roccas & Brewer, 2002). Unlike political tolerance, social tolerance focuses on outgroups’ social and cultural practices (Cvetkovska et al., 2020). It can take several forms of intergroup positivity. Indeed, work analyzing the consequences of SIC on social tolerance has been carried out in a variety of intergroup contexts, some of which may appear soft and others more hard. In the first category, we can cite studies focusing on attitudes towards affirmative action policies and multiculturalism in the United States (Brewer & Pierce, 2005), intergroup biases in Holland (Verkuyten & Martinovic, 2012), or attitudes towards diversity in Australia (Brewer et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2009). For the present research, these works, which all validate the hypothesis that SIC predicts tolerance towards outgroups, however, have the disadvantage of having been conducted in a Western democratic context, where the level of brutality and discrimination towards subordinates is somehow constrained, indirect and covered because of the cultural ideal of equality of all before the law (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999).Researches in the second category do not have the contextual disadvantage noted above. We can list the studies by Branković et al. (2015) or Maloku et al. (2018) for example, which were conducted in intergroup contexts where the protagonists had violent historical backgrounds. Research reports that these antecedents could contribute to creating psychological barriers to the harmony of contemporary intergroup relations (see Dzuetso Mouafo et al., 2024; Vollhardt & Nair, 2018). Indeed, in post-conflict situations, individuals who are confronted with the threat represented by the outgroup prefer clearly circumscribed intergroup boundaries (Roccas & Brewer, 2002); hence their low inclination towards intergroup positivity. In support of this idea, research by Branković et al. (2015), who analyzes social distancing between young Serbs and Bosniaks, by comparing SIC and SII, reports that SIC, unlike SII, does not predict social tolerance. In the same vein, the study by Maloku et al. (2018), conducted in Kosovo, assesses the intention of Albanians and Serbs to engage in intergroup contacts through SIC, in a region that experienced a violent conflict period of clashes, mutilations and killings and which immersed in a highly segregated social climate, characterized by intergroup rejection (Judah, 2008; Maloku et al., 2016, 2018). This study reports that while SIC has a positive impact on the willingness to engage in intergroup contacts among members of the majority ethnic group (Albanians), this is not the case among members of the minority ethnic group (Serbs). Furthermore, even among members of the majority group, SIC scores observed by Maloku et al. (2018) are not as significantly higher than the exponential scores generally recorded in closely divided intergroup contexts. These results suggest that in harsh intergroup contexts, the ability of SIC to predict intergroup positivity may be questioned. This is why this study suggests that it should be further tested in empirical contexts where the level of intergroup cleavage is important, to assess the robustness of its predictions. Without being exhaustive, this would be the case with the situations of the Rohingya in Myanmar (see Habib, 2021; Manikandan, 2019) or LGBTQ people in the African context (see Dzuetso Mouafo, 2023; Dzuetso Mouafo et al., 2023) for example.To solve the methodological problems noted above, the present study proposes a new process to capture the multiple identities of ingroup members at the same time as those of outgroup members. This proposition consists of the evaluation of the perceived inclusion of outgroup members within individuals’ ingroups.

1.3. The Contribution of the Current Research to the Theoretical Perspective of Multiple Identities: The Perceived Inclusion of an Outgroup Members within individuals’ Ingroups (PIOMI)

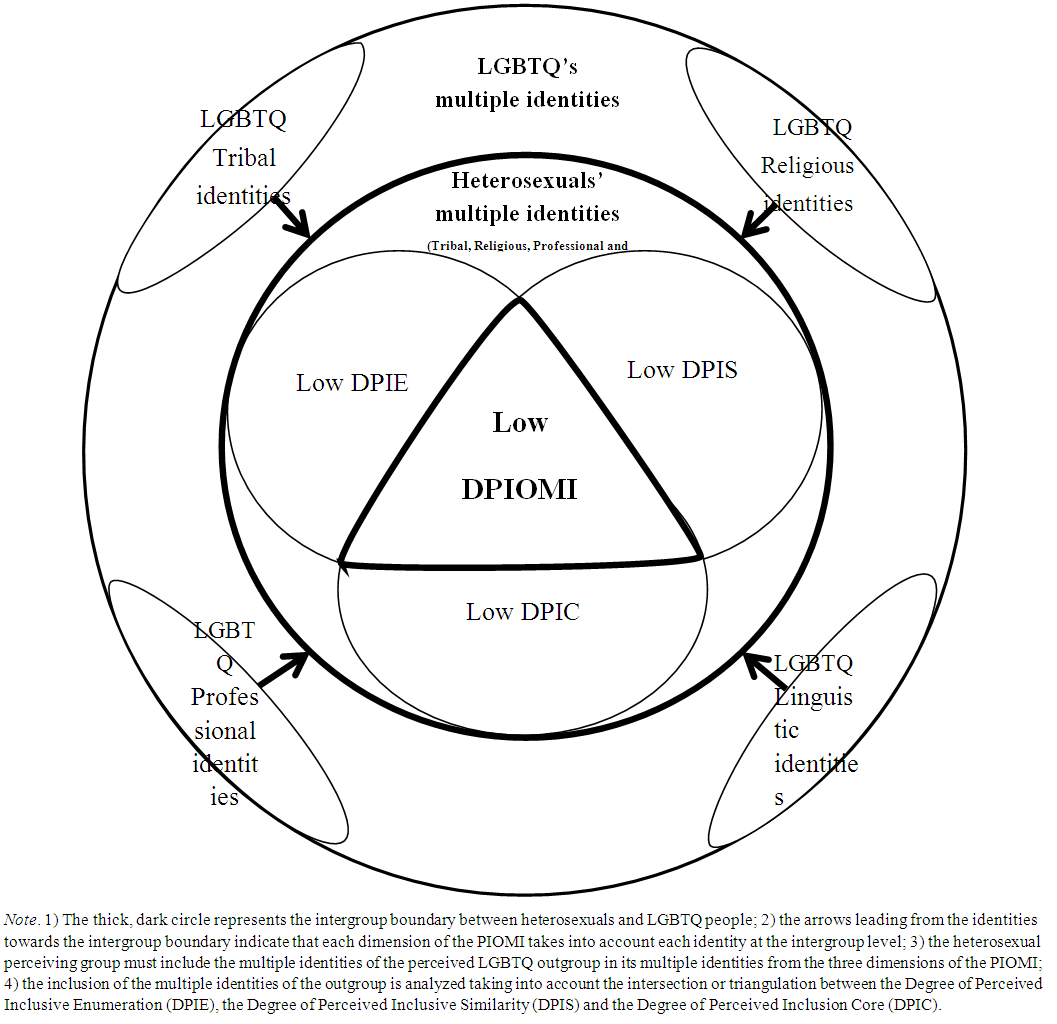

- The need to belong is a fundamental human motivation (Brewer, 1991; Fiske, 2004). This means that social exclusion compromises every individual’s inalienable right to belong to social collectives (Hutchison et al., 2007), constituted on the basis of identity markers such as religion, ethnicity or language. This research, which focuses on social inclusion, is part of this logic. Concretely, it proposes to the literature the concept of Perceived Inclusion of an Outgroup Members within individuals’ Ingroups (PIOMI). Specifically, this construct refers to the inclusion of the multiple identities of the perceived outgroup within the multiple identities of the perceiving ingroup. It helps fill the limitations of the literature on SIC noted in this study on several points.First, to fill the limit relating to the non-capture, by SIC, of the identity plurality of the perceived group (the outgroup) at the same time as the identity plurality of the perceiving group (the ingroup), PIOMI is part of the prospect of a simultaneous capture of the socio-identity plurality of these two groups. It thus takes up the proposition relating to the possibility that the identity plurality of a member of a perceived outgroup can be deployed within the various ingroups of a perceiving individual (see Brewer, 2010; Xin & Xin, 2012). Indeed, even if individuals have different category memberships on an identity dimension made salient in a situation (Licata, 2007), it remains that they are also likely to have similar category memberships on other dimensions (see Grigoryan et al., 2020). This means that due to the identity plurality which characterizes all individuals, ingroup/outgroup memberships are always limited to one or a few identity markers. For example, faced with a Black, Christian and heterosexual person, a Black, Christian and homosexual person will belong to the same ingroups for the racial and religious identity markers, but will be a member of the outgroup if we place ourselves in the perspective of the identity marker relating to sexual orientation. Because of this, the present research considers that the socio-identity plurality of the members of the perceived outgroup (homosexuals in this case) deserves, as much as that of the perceiving ingroup (heterosexuals in this case), to be taken into account in the methodological procedures of researches relating to identity plurality. This procedure would have the advantage of making it possible to judge whether, and under what conditions, the multiple group memberships that the perceiver shares with the perceived have the capacity to neutralize or not the salient identity marker on which they diverge. In this vein, the measurement that results from the PIOMI aims to evaluate the degree of the PIOMI. Furthermore, unlike SIC for example, which often assesses, at the level of tolerance measures, the attitudes of perceivers towards several diffuse outgroups (see Brewer & Pierce, 2005; Brewer et al., 2012), PIOMI is contextualized and specified in relation to a single outgroup, following the principle that in each social situation, it is generally a single group characteristic (therefore a single outgroup) which is highlighted.Secondly, to fill the limit of SIC relating to the paradox of the neutralization of the socio-identity plurality of the perceiver, the PIOMI keeps this plurality constant throughout the process of its evaluation. This means that the perceiver’s primordial group memberships, activated by the GEQ, remain active until the end of the evaluative process. Indeed, as noted above, one of the defects of research on SIC (see for example Schmid et al., 2009; Verkuyten & Martinovic, 2012) is that by activating the identity marker differentiating the outgroup from the perceiver’s ingroup, they activate, in an induced way, the identity singularity of the perceiver, since the identity marker salient among the outgroup is likely to also become salient among the multiple ingroups of the perceiver. This means that if we evaluate the tolerance of a Black, Christian and heterosexual individual towards homosexuals, it is likely that his race and religion have less impact on his attitude than his sexual orientation (heterosexuality), made salient by the fact that it is the sexual orientation of the perceived person (homosexuality) which has been activated. By evaluating the perceived inclusion of the multiple identities of the outgroup in the multiple identities of the ingroup, PIOMI resolves the problem of the salience of a dimension of the identity of the outgroup by inducing, among perceivers, the idea that the members of this outgroup can, on certain dimensions, share the same ingroups as them. This procedure can therefore lead them not to focus on the differentiating identity marker, since the PIOMI is a measure of the perceived inclusive overlap of the outgroup’s identity plurality. Third, unlike SIC which is a predictor of tolerance (Roccas & Brewer, 2002), the PIOMI is in itself a measure of social tolerance via social inclusion. Indeed, the approach of the research on SIC, which consists of measuring on the one hand the identity complexity of the perceiver, then administering a scale of tolerance towards the outgroup (external to the SIC) on the other hand, is likely to create a phase shift between SIC and its object, by neutralizing perceiver’ identity plurality. This approach has the consequence of questioning the predictive effect of SIC on social tolerance, in the absence of a control group in which SIC would not be activated. In other words, we can wonder if it is indeed the awareness, by individuals, of their identity complexity activated by the GEQ which impacts on tolerance, since their level of tolerance towards the outgroup is not compared with that of other individuals who would not have been made aware of this complexity by not administering the GEQ to them (a control group). To remedy this, the development of the PIOMI was part of the perspective of Bogardus (1925), who carried out an evaluation of tolerance by the inclusion of the outgroup in the perceivers’ socio-geographical ingroups (members of my family; members of my group of close friends; residents on the same street; colleagues in the same company; citizens of the same country; visitors to my country; and excluded from my country). The level of tolerance of the outgroup is all the stronger as the perceiver accepts the outgroup members in its closest ingroups (member of my family or my group of close friends for example). In this vein, PIOMI has three levels in its assessment of the perceived inclusion of the outgroup multiple identities into ingroup multiple identities: 1) a low degree of inclusion amounting to exclusion of the outgroup; 2) an average degree of inclusion which refers to the tolerance of the outgroup; and 3) a high degree of inclusion which refers to acceptance of the outgroup. Due to the fact that research conducted within sociopolitical contexts where the groups involved have a history of conflict calls into question the ability of SIC to predict intergroup positivity (see Branković et al., 2015; Maloku et al., 2018), the present study considers that it is within this type of context that PIOMI can be meaningfully constructed and tested. In doing so, it hopes to provide an explanation for the collapse of SIC as a predictive factor of tolerance in situations where the outgroup represents a threat to the ingroup, as is the case in a post-conflict (see Hall, 2014) or post-segregation (see Dixon et al., 2023) contexts for example. This is why it is interested in the social inclusion of LGBTQ people in the highly heteronormative context of Cameroon. In this country, not only is homosexuality condemned by law, but it is also considered by popular imagery as a curse, a sin, a dishonor, a mental imbalance or a sectarian practice (Lado, 2011; Menguele Menyengue, 2016). This situation explains the violence, abuse and ostracism suffered by LGBTQ people (Amnesty International, 2013; Human Rights Watch, 2021), considered as a threat to heterosexuals.

1.4. The Intergroup Context of the Research: Social Inclusion of LGBTQ People in a Highly Heteronormative Context

- Inclusion is the principle of recognizing the right of all individuals to full participation in all aspects of society. It is an individual right and a societal responsibility that requires the removal of barriers and social structures constituting obstacles to the full participation of all. In this sense, it depends not only on the acceptance of difference, but also on the desire to celebrate diversity, which requires a favorable environment and the political will to combat discrimination and promote equality (Jones, 2011). Unfortunately, for many individuals and groups, inclusion remains a principle that comes up against a difficult and even brutal reality. This is the case for LGBTQ people (see Flores, 2021), who daily face exclusion, discrimination and violence within the societies in which they evolve (see Braganza & Hodge, 2024; Hartmann-Tews, 2022; Martìnez-Guzmán & Íñiguez-Rueda, 2017; Moleiro et al., 2021; Tillewein et al., 2023). Indeed, even if more or less significant progress has been noted in various countries on the specific rights of LGBTQ people, such as the depathologization of being transgender or the legalization of same-sex marriages (Brandtzæg Godø et al., 2024), it remains that in other contexts, notably those characterized by a marked tendency towards heteronormativity (Gulevich et al., 2018), these people who represent a threat to certain community, moral and ideological values (Adamczyk & Pitt, 2009; Marchlewska et al., 2019; Tjipto et al., 2019) are experiencing the repercussions of these global progressive trends (Salvati & Koc, 2022).Concepts such as homophobia (Herek, 2000; Weinberg, 2010), transphobia (Nagoshi et al., 2008), homonegativity (Hudson & Rieketts, 1980), homoprejudice (Logan, 1996), heterosexism (Herek, 2004) or sexual prejudice (Chonoby, 2013) refer to all biased attitudes relating to sexual orientation (Castiglione et al., 2014; Flórez-Salamanca, 2014). Generally shared by heterosexuals (Messanga & Sonfack, 2017), these attitudes are impacted, among other things, by gender, quantity and quality of contact experiences with members of the outgroup, as well as adherence to religious and hegemonic beliefs (Cunningham & Melton, 2012; Gkinopoulos et al., 2024; Kanamori & Xu, 2022; Ncanana & Ige, 2014; Rodriguez-Seijas, 2014). They are the basis of discriminatory policies and behaviors to which members of the LGBTQ community are victims in many countries. Indeed, some of them criminalize, through sodomy laws (Dionne et al., 2014), consensual relations between people of the same sex (59% of African countries and 52% of Asian countries that are members of the United Nations). Others have, in their legal and regulatory arsenal, legal provisions which restrict freedom of expression on subjects related to sexual orientation, gender identity and sex education, or prohibit the promotion or propaganda on homosexuality and censor films and media (37% of African countries and 40% of Asian countries members of the United Nations). Only 30% of United Nations member countries, the majority of which are in Europe (68%), have legislation against discrimination based on sexual orientation and 18% recognize the equality of relations between people of the same sex and/or extend the definition of marriage to same-sex unions (Salvati & Koc, 2022).In the African context, it is often the defense of family and cultural values that serves as the sociocultural and ideological foundation of anti-LGBTQ legislation. Indeed, the official explanation for these laws is the protection of the African heterosexual family against the dangers of homosexuality, conceived as antisocial, anti-kinship, and anti-procreative. Therefore, every African adult must start a family and/or procreate. Anyone who transgresses pro-marriage and pronatalist ideologies by deliberately adopting an unconventional sexual identity or non-reproductive sexual practices is exposed to legal persecution and social ostracism (Ndjio, 2020). These homonegative attitudes and behaviors are all the more significant since in a country like Cameroon, for example, popular imagery does not perceive sexual relations between people of the same sex as the result of a sexual orientation, but rather as a deliberate choice made by individuals motivated by the desire for social mobility and promotion (Gueboguo, 2006). This choice would be justified concretely by a crisis context characterized by the scarcity of jobs which would push young people in search of socio-professional integration to get closer to the political-administrative elites who, in turn, would condition their intervention in their favor with potential employers by homosexual relationships (Messanga & Sonfack, 2017). In this context, these relationships are seen more as conditions for entry into circles of power and money (Gueboguo, 2006). This perception is the basis of conspiracy theories relating to this type of relationship and the people involved. These theories consist of the belief that two or more actors have secretly coordinated to achieve an objective of public interest, but without the public’s knowledge (Douglas & Sutton, 2023; Douglas et al., 2024). Relating to LGBTQ people specifically, they are linked to the alleged existence of an LGBTQ lobby whose role would be to spread homosexuality throughout the world through the indoctrination of minors, the disruption of the natural/moral order, and an ideology based on the controversial “gender theory” (Salvati et al., 2023). They flourish in both the Western (see Friedersdorf, 2012; Salvati et al., 2024) and African contexts (see Dzuetso Mouafo, 2023; Dzuetso Mouafo et al., 2023) and impact on the social distance between heterosexuals and LGBTQ people (Gkinopoulos et al., 2024). This is particularly the case in Cameroon, the empirical setting of the present study.Unlike other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, in Cameroon, accusations of homosexuality are made by citizens, against the State and elites. They serve to express popular dissatisfaction with institutional authorities and their practices of illicit enrichment. These authorities are accused of being part of secret societies of Western origin (Freemasonry, Illuminati and Rosicrucianism in particular), which would promote homosexual practices. This belief is based in particular on the alleged role of the French Medical Doctor, Louis Paul Aujoulat, considered as a homo-Masonic (homosexual and Freemason) colonial figure (Orock & Geschiere, 2021). According to popular imagery, he would be the “initiator” of membership in secret societies and homosexual practices of the Cameroonian political and administrative elite who were to take over after the colonial period (Nken, 2014). This is why, within public opinion, certain homophobic discourses find their sources in the alleged ritual and initiatory uses of homosexuality (Roxburg, 2019), conceived as an occult practice (Menguele Menyengue, 2016) or a form of vampirism promoted by esoteric brotherhoods (Menguele Menyengue, 2014). The members of these brotherhoods, many of whom are recruited from senior administration and business circles, would practice incest, homosexuality and ritual crimes accompanied by sodomy (Tonda, 2002 cited by Menguele Menyengue, 2016). This belief underlies the neologism anusocracy (see Geschiere & Orock, 2021) i.e. the government of the anus, which refers to the perception of the anus as a source of wealth and power. This neologism establishes the idea that sodomy is used in circles of power and money to humiliate and submit individuals in search of social promotion (Pigeaud, 2011).The consequence of belief in the mystical and clientelist dimensions of homosexuality is that many Cameroonians perceive it as an unnatural practice, since people can be initiated or converted to it (Machikou, 2009). This is one of the sources of the rejection of LGBTQ people (Dzuetso Mouafo, 2023), which manifests itself concretely in the humiliations, ambushes, arbitrary arrests, beatings, torture and assassinations targeting them (Lyonga, 2022; Messanga & Sonfack, 2017; Olivier, 2019). These discriminatory and violent acts are perpetrated in a favorable sociocultural and legal context, since homosexuality is considered a criminal offense punishable by imprisonment of up to five years (Dzuetso Mouafo et al., 2023). This particularly hostile environment pushes LGBTQ people to adopt strategies to camouflage their sexual orientation, sometimes going so far as to engage in heterosexual relationships or even enter into sham marriages (Gueboguo, 2006).

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- 666 Cameroonians (335 men and 331 women) agreed to participate voluntarily in this study. They all declared themselves heterosexual. They were divided into two subsamples. The first was used for the exploratory validation of the DPIOMI scale. The second made it possible to ensure the confirmatory and invariance tests, as well as the construct, discriminant and predictive validities of the DPIOMI scale. From the point of view of research ethics, guarantees were given to them regarding the preservation of the confidentiality of their responses and their exclusive use for scientific purposes. (i) Subsample AThe exploratory factorial test of the DPIOMI measurement scale was carried out on a sample of 200 heterosexuals (103 men and 97 women) aged on average 26.06 years (SD=7.85). These are people belonging to various linguistic, socio-professional, religious and tribal groups. (ii) Subsample B To test the confirmatory factorial structure, the invariance of the developed instrument, its construct and discriminant validities and provide various explanations for the degree of inclusion of LGBTQ people in the participants’ ingroups, a sample of 466 people was selected. Their age varies between 18 and 52 years (M=25.15; SD=7.15). Just like their counterparts in Sample A, they belong to various linguistic, socio-professional, religious and tribal groups.

2.2. Construction Procedure and Description of the DPIOMI Scale

- The DPIOMI measurement scale is strongly inspired by SIC’s methodological tools (see Brewer & Pierce, 2005; Roccas & Brewer, 2002), but it differs on a few points. Indeed, SIC assesses the degree of perceiver’s identity complexity, that is to say the degree of overlap that he perceives within the groups to which he simultaneously belongs. It has two dimensions: Overlap Complexity (OC) and Similarity Complexity (SC). SIC items, constructed on the basis of preliminary studies by Roccas and Brewer (2002), generally take into account four important identities of the participant, revealed by the GEQ. This leads to the formulation of 12 items based on all possible pairings of the groups to which an individual belongs to the OC and 6 items to the SC; hence the total of 18 items, when the tools of the two dimensions are administered simultaneously. The items on these two scales are neither worded nor coded in the same way. Furthermore, the interpretation of the scores resulting from the statistical analysis is not done according to the logic of traditional scales. For example, a high score on the overlap scale refers to low SIC and vice versa. The DPIOMI scale, for its part, is located in another methodological perspective.The DPIOMI scale assesses the inclusion of the identity plurality of an X outgroup in the identity plurality of the ingroup. It therefore measures inclusive complexity. Its evaluation procedure fits into the logic of measuring SIC at the level of GEQ, but detaches from it at the level of the evaluation itself. Like SIC, it takes into account four essential identities of the individual to construct group matches. It has a total of 17 items distributed over three specific dimensions. The first dimension is Perceived Inclusive Enumeration (PIE). It informs the researcher not only about perceiver’s awareness of the existence of X outgroup, but also about the understanding of the fact that the members of this outgroup potentially have the same group memberships or the same social identities as their own. This first dimension is specifically inspired by the first dimension of the SIC (see Roccas & Brewer, 2002). It has 8 items. For example, an item asks: « Selon vous, environ combien de personnes LGBTQ y-a-t-il dans votre tribu ? (According to you, approximately how many LGBTQ people are there in your tribe?) » The second dimension is Perceived Inclusive Similarity (PIS). It is essentially inspired by the second dimension of the SIC. It evaluates the similarity that the perceiver admits between the members of X outgroup and the members of his primordial ingroups. Indeed, if the perceiver is aware of the socio-identity plurality of the members of the outgroup, which he counts in his ingroups, we assume that he is likely to perceive points of similarity between this outgroup members and himself. This dimension has 5 items. One of them suggests that: «À votre avis, environ combien de personnes LGBTQ ressemblent-elles aux membres de votre groupe religieux (Catholiques/Protestants/ Musulmans)? (According to you, approximately how many LGBTQ people do you think are like members of your religious group (Catholics/Protestants/Muslims)?) » The third dimension constitutes the heart of the measurement. This is the Perceived Inclusion Core (PIC) or the inclusion of members of the outgroup into the ingroups. It has 4 items. For example, an item states that: « Quand vous pensez à toutes les personnes LGBTQ, combien en incluez-vous (c’est-à-dire acceptez-vous d’intégrer) comme membres de votre tribu? » (When you think of all LGBTQ people, how many do you include (i.e. do you accept to integrate) as members of your tribe?). All items on the DPIOMI scale are coded on a 10-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 (none) to 9 (all).

2.3. Instruments of Data Collection

- This study used various instruments of data collection during its exploratory and confirmatory phases. These instruments were written in the French language.

2.3.1. The Measures of the Exploratory Phase

- During this phase, the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (age, gender or sexual orientation) were previously collected. Then, their group memberships were generated through the GEQ, before the administration of the measure of the perceived inclusion of the multiple identities of the outgroup members in their primordial ingroups. This assessment was made using the DPIOMI scale. Like for the SIC measures, the GEQ precedes the DPIOMI scale. Its evaluation procedure follows the logic of measuring the SIC at the level of GEQ, but it departs from it at the level of the evaluation itself. To construct group matches, DPIOMI takes into account four essential identities of the individual, namely tribal, religious, linguistic and professional identities. This measure is self-administered.Following the example of previous researches (Brewer et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2009), the present study used the GEQ to elicit participants’ primordial memberships. Based on the diversity of their affiliations, we only retained those who attach importance to the same group affiliations. Indeed, the literature reports that individuals who attach importance to affiliations such as recreational, political or associative groups are few in number in Cameroon, compared to individuals who attach great importance to their tribal, linguistic, religious and professional affiliations, for historically anchored reasons (see Messanga, 2018; Tièmeni Sigankwe, 2019; Tsogo À Bebouraka, 2023; Tsogo À Bebouraka et al., 2023). These observations from the literature underlie the construction of the items of the DPIOMI scale on the basis of these four social identities. The high scores recorded on the identification scale for each of these four group affiliations support the approach of this study.

2.3.2. The Measures of the Confirmatory Phase

- In the confirmatory phase of the evaluation of the metrological qualities of the DPIOMI scale, several measuring instruments were administered in order to ensure its construct, discriminant and predictive validities. These measures assess the following constructs:Degree of Perceived Inclusion of an Outgroup Members within individuals’ Ingroups (DPIOMI)At the end of the exploratory phase, 12 items out of the 17 items of the constructed version of the scale were retained. 5 items were eliminated because they presented double factor loadings greater than or equal to 0.40. The reliability analysis indicates that the DPIOMI scale is reliable (ω=.92; α=.92). Its dimensions are also (PIE (ω=.88; α=.88); PIS (ω=.87; α=.86); PIC (ω=.88; α=.88)). The positioning of participants on the items of this measure is ensured using a scale coded between 0 (none) and 9 (all).Degree of Identification as heterosexualA single item makes it possible to assess participants’ degree of identification as heterosexual. It asks them: «À quel point votre orientation sexuelle (barrez la mention inutile: Hétérosexuelle/Homosexuelle/Bisexuelle/Pansexuelle) est-elle importante pour vous?» (How important is your sexual orientation (cross out what doesn’t apply: Heterosexual/Homosexual/Bisexual/Pansexual) to you?)Anomic threatTo assess the perception of anomic threat, three items adapted from Teymoori et al. (2016) were used. For example, an item suggests that: « Dans ce pays, les standards de la morale ne sont plus véritablement respectés » (In this country, moral standards are no longer truly respected). They are evaluated on a 7-point coded scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). This measure is reliable (ω=.80; α=.80).Conspiracy beliefs Participants indicated their opinions on six items taken from the Gender Ideology and LGBTQ+ lobby Conspiracies scale (GILC; Salvati et al., 2023). These items relate to the dimension relating to the conspiracy of the LGBTQ+ lobby. One of them proposes that: « Il existe une organisation de personnes très puissantes qui profitent des instances LGBT pour établir une dictature de la pensée unique » (There is an organization of some very powerful people who take advantage of LGBT instances to establish a dictatorship of single thought). A Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) is associated with it. This measure is reliable (ω=.89; α=.89).Intergoup emotions Several measures using a Likert-type response format, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), were used to assess participants’ emotions towards LGBTQ people.(i) Distrust This emotion was assessed using three items (e.g., « Les personnes LGBTQ doivent être surveillées » (LGBTQ people should be watched)). This measure is an adaptation of Rusk’s (2018) distrust scale. It is reliable (ω=.75; α=.75).(ii) Fear This emotion was assessed by an adaptation of Giner-Sorolla and Russell (2019). It has three items, one of which states: «Les personnes LGBTQ sont vraiment effrayantes» (LGBTQ people are really scary). This measure is reliable (ω=.84; α=.83).(iii) Anger Three items adapted from Giner-Sorolla and Russell (2019) were used to measure this emotion. One of these items suggests that: « Je peux parfois sentir mon cœur battre plus vite à cause de la rage que je ressens quand je commence à penser aux personnes LGBTQ » (I can sometimes feel my heart beating faster because of the rage I feel when I start thinking about LGBTQ people). This measure is also reliable (ω=.85; α=.85).(iv) Hatred The evaluation of the participants’ hatred towards the LGBTQ outgroup was done through three items adapted from Sternberg and Sternberg (2008). One of them indicates that: « La lutte contre les personnes LGBTQ est importante en Afrique quels que soient les coûts possibles » (The fight against LGBTQ people is important in Africa whatever the possible costs). The reliability of this measure is acceptable (ω=.86; α=.86).(v) Disgust Disgust was assessed with three items from the Hodson et al. measure (2013). One of these items states: «Je demanderai de nouveaux draps de lit dans un hôtel, si le précédant occupant de la chambre était une personne LGBTQ» (I would ask for new bed sheets in a hotel if the previous occupant of the room was an LGBTQ person). The reliability of this measure is acceptable (α=.750).Opposition to LGBTQ rightsTwo items from the scale of Smeekes et al. (2011) were adapted and used to assess opposition to LGBTQ rights (α=.62). For example, one reverse-coded item states that: « Au Cameroun, les homosexuels ont le droit de s’exprimer dans l’espace public » (in Cameroon, LGBTQ people have the right to express themselves in public space). A Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) is associated with it.Prejudice towards LGBTQ people Three items from the measure developed by Yu et al. (2011) were used to measure this construct. The response format is a 7-point Likert scale. One item in this measure suggests that: « Le nombre croissant des personnes LGBTQ indique un déclin des mœurs sociales dans ce pays » (The growing number of LGBTQ people indicates a decline in social morals in this country). This scale is reliable (ω=.81; α=.80). Daily discrimination against LGBTQ peopleTwo items from the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Ulusoy et al., 2023) were adapted to measure daily discrimination against LGBTQ people. One of these items proposes that: « Les personnes LGBTQ devraient être traitées avec moins de courtoisie » (LGBTQ people should be treated with less courtesy). These items use a 7-point response format, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly agree). This scale has good internal consistency (α=.81). Physical aggression towards LGBTQ peopleTwo items adapted from the study by Buss and Perry (1992) measure attitudes towards physical aggression against LGBTQ people among participants. For example, item 2 proposes that: « Si je dois recourir à la violence pour protéger les valeurs de l’hétérosexualité, je le ferai » (If I have to resort to violence to protect the values of heterosexuality, I will do so). This measure is reliable (α=.66) and its response format consists of a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly agree).Hostility towards LGBTQ people To assess participants’ hostility towards LGBTQ people, three items inspired by Schaafsma and Kipling (2012) were used. One of these items states: « Je voudrais blesser les personnes LGBTQ » (I would like to hurt LGBTQ people). Responses to the items are made following a 7-point Likert-type format, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly agree). The internal consistency index of this measure is acceptable (ω=.89; α=.89).Social Identity Complexity (SIC)SIC assesses the degree of overlap that an individual perceives within the groups to which he or she simultaneously belongs. It has two dimensions, namely overlap complexity (e.g. « Quand vous pensez à tous les membres de votre tribu, combien sont également membres de votre groupe religieux? » (When you think of all the members of your tribe, how many are also members of your religious group?) and similarity complexity (e.g. « En général, l’individu typique de votre tribu est très similaire à l’individu typique de votre groupe professionnel » (In general, the typical individual of your tribe is very similar to the typical individual in your professional group). The set of SIC items, constructed on the basis of preliminary studies by Roccas and Brewer (2002), generally take into account four important identities to which the participant identifies at the level of GEQ. The overlap complexity measure uses a 10-point Likert-type response format, ranging from 0 (none) to 9 (all). It is reliable (α=.91; ω=.92). The similarity complexity measure, on the other hand, uses a 7-point response format, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly agree). This scale is also reliable (α=.87; ω=.87).

2.4. Data Analysis Procedure

- In this study, the statistical software SPSS.27 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) was used to manage missing values by automatically replacing them with the mean of the series. This software also made it possible to code sociodemographic variables. The JASP.17.1 software (Jeffreys’s Amazing Statistics Program) was used to perform descriptive statistics (Means and Standard Deviations), determine Pearson coefficients (r) and explore the factorial structure of the DPIOMI scale. To analyze the quality of the items in order to reduce the instrument based on the relationships between all the manifest variables and the latent factors and their level of validity, multivariate statistical techniques such as exploratory factor analyzes (EFA) using the rotation method orthogonal Varimax were applied. The scree plot (Cattell, 1966), the explained variance of the factor model and the factor loadings were estimated (Raykov & Marcoulides, 2011). Measures of Sampling Adequacy (MSA; Kaiser, 1974) and Bartlett’s chi-square (χ2) were also determined. These methods made it possible to summarize and extract the latent factors of the DPIOMI. Items with very low loadings (FC≤.30) were considered for deletion (Boateng et al., 2018). To give the most credence to the reliability of the scale, the present research followed the recommended ideal procedure (Boateng et al., 2018), which consists of constructing the scale on a first sample, whether cross-sectional or longitudinal, then to test it on a second independent sample. The reliability of the elements and that of the latent factors explored, as well as the complete correlation of the corrected manifest variables (CI-TC) were evaluated using the alpha (α) models of Cronbach (1951) and the omega (ω) models of McDonald (1999) in both samples.The confirmatory test of the first and second order factor structure and the analysis of the invariance of the DPIOMI scale are carried out under JASP.17.1 by executing the Lavaan syntax. The overall fit of all confirmatory factor models (CFA) was tested using the chi-square goodness-of-fit test. This test was supplemented by alternative adjustment indicators (Kline, 2016). Among these fit indicators, the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) is based on the idea of comparing the proposed factor model to a model in which no relationship is assumed between the variables, while the fit coefficient Comparative Fit Index (CFI) is an incremental relative fit index that measures the relative improvement in the fit of the developed model compared to that of a reference model (Boateng et al., 2018; Hu & Bentler, 1999). The CFI index (CFI≥.95, acceptable fit) and the TLI index (TLI≥.95, reasonable fit), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA≤.08, reasonable fit) and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR≤.06, acceptable fit) were examined. The developed latent and manifest variable measurement models were improved based on the model modification indices. Factor loadings are acceptable from .40 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). A higher order factorial structure, in which the correlations between the main factor (DPIOMI) and its three latent factors (PIE, PIS and PIC) were established and its structural adjustment coordinates were determined (Boateng et al., 2018).The DPIOMI scale equivalence test establishes evidence of configural (the model is the same across groups in qualitative terms), metric (equality of factor loadings between groups), and scalar invariances (unbiased statistical comparison of the means on the latent constructs) of this scale among men and women. It checks whether the men and women in the sample will respond in the same way overall to the same items of the DPIOMI scale. This test makes it possible to verify whether this scale does not suffer from a problem of measurement equivalence between groups, as is often the case with certain psychometric scales. Metric invariance was tested by constraining the factor loadings to intergroup equality, by labeling the loadings in the Lavaan syntax. Comparison of relative fits of multi-group CFA models using scaled Chi-square (χ²) difference tests was performed (Kline, 2016). A value of Δχ² was calculated. If it is insignificant (p>.05), this indicates that there is metric invariance. The ΔCFI was estimated and a value of ΔCFI<.01 indicates a parsimonious model constrained by equality (Cheung & Lau, 2012; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). The AIC/BIC value was calculated and the lowest value indicates the best compromise between model fit and model complexity (van de Schoot et al., 2012). Since metric invariance does not allow comparing scores on latent factors between groups, this involves comparing structural relationships between latent variables between groups. To ensure scalar invariance, the average scores on the three DPIOMI factors were compared without bias and the intercepts were introduced so as to label the two sexes identically, in order to constrain them to be equal.In addition to validating the scale structure, the DPIOMI is predicted by intergroup cognitions and affects. Thus, the correlation coefficients and the linear regression model involving the latent and manifest variables were estimated by running the Lavann syntax from the JASP software 17.1. A general explanatory model of the perceived social inclusion of LGBTQ minorities involving the latent variables was carried out using AMOS.23. Based on all these results, PIOMI was summarized through a summary model of its application in highly heteronormative contexts.

3. Results

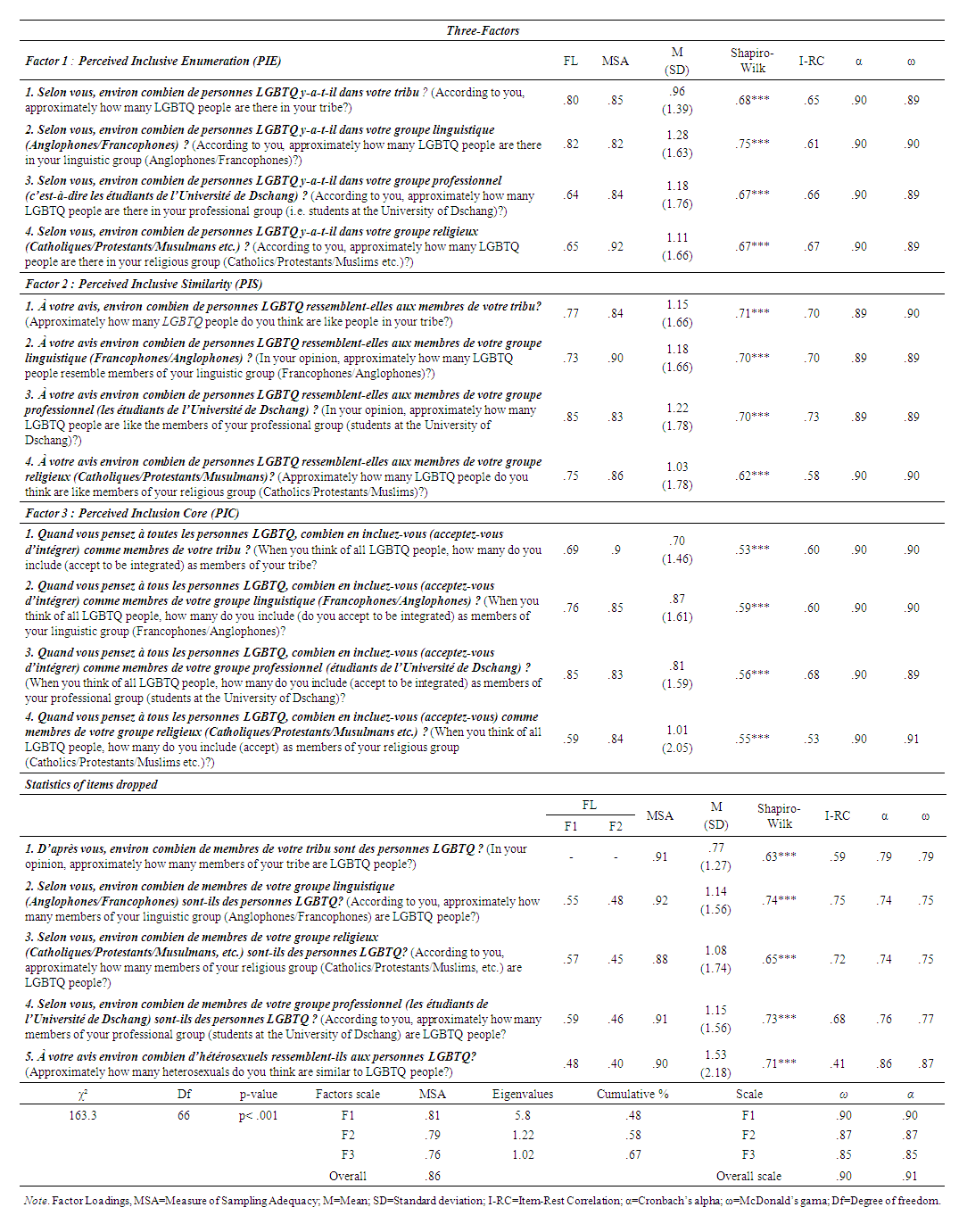

3.1. Exploratory Tests of Latent Factors of the Internal Structure of the DPIOMI Scale

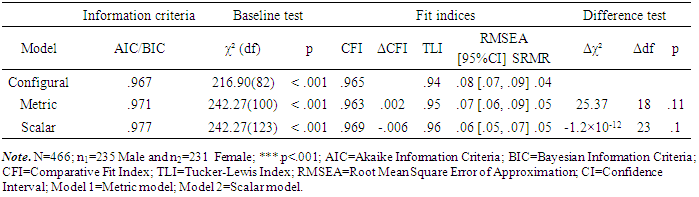

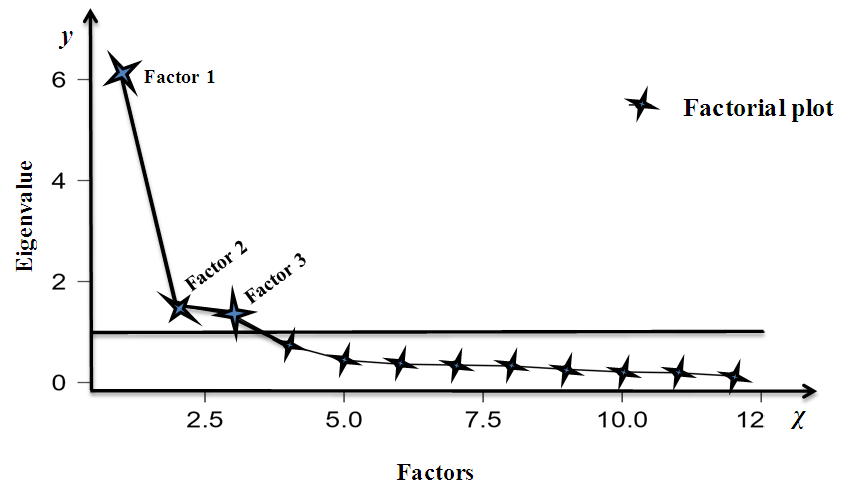

- Exploratory factor analyzes summarize the structure of the DPIOMI into three factors: Perceived Inclusive Enumeration (PIE), Perceived Inclusive Similarity (PIS) and Perceived Inclusion Core (PIC). On the basis of the factor loadings, the structure of the scale went from 17 items (the unifactorial version) to 12 (the trifactorial version), i.e. 4 items for each of the three factors. These elements are those which make it possible to finely capture the degree of perceived inclusion of the identity plurality of the LGBTQ outgroup in the identity plurality of the heterosexual ingroup, and whose factor loadings vary between .48 and .85 (see Table 1). It is this logic which underlies the elimination of the five (05) items, four (04) of which had double factor loadings greater than .40 while one (01) did not saturate with any factor (Nunnally, 1978). This indicates that factor loadings do not vary uniquely (Boateng et al., 2018). The descriptive statistics also indicate that the items retained have average distributions which vary from .70 to 1.28. These low average trends indicate very low inclusion of LGBTQ people in the different participants’ ingroups. The reliability indices of the extracted items and factors are acceptable. Those of the items vary between .89 and .90 according to the Cronbach alpha method (Cronbach, 1951) and between .89 and .91 according to the McDonald method (McDonald, 1999). According to these reliability estimation methods, the DPIOMI factors are reliable. The same is true for the global scale (see Table 1). Inter-item relationships range from .53 to .70. These statistical parameters indicate that the 12 observed factors summarize the internal structure of the DPIOMI measurement into 3 latent factors constituting a three-factor model with Eigenvalues varying between 5.8 to 1.02. The variance explained by the three-factor model is estimated at 67% (see Table 1); hence the scree plot graph in Figure 1.

| Table 1. Item statistics of the DPIOMI scale |

| Figure 1. Scree plot |

3.2. Confirmatory, Invariance, Construct, Discriminant and Predictive Validities Tests of the DPIOMI Scale

- The results of these analyzes come from sample B of the study and are obtained from the measurements administered during the confirmation phase of the factorial structure of the scale.

3.2.1. CFA-SEM of the Structure of the DPIOMI Scale

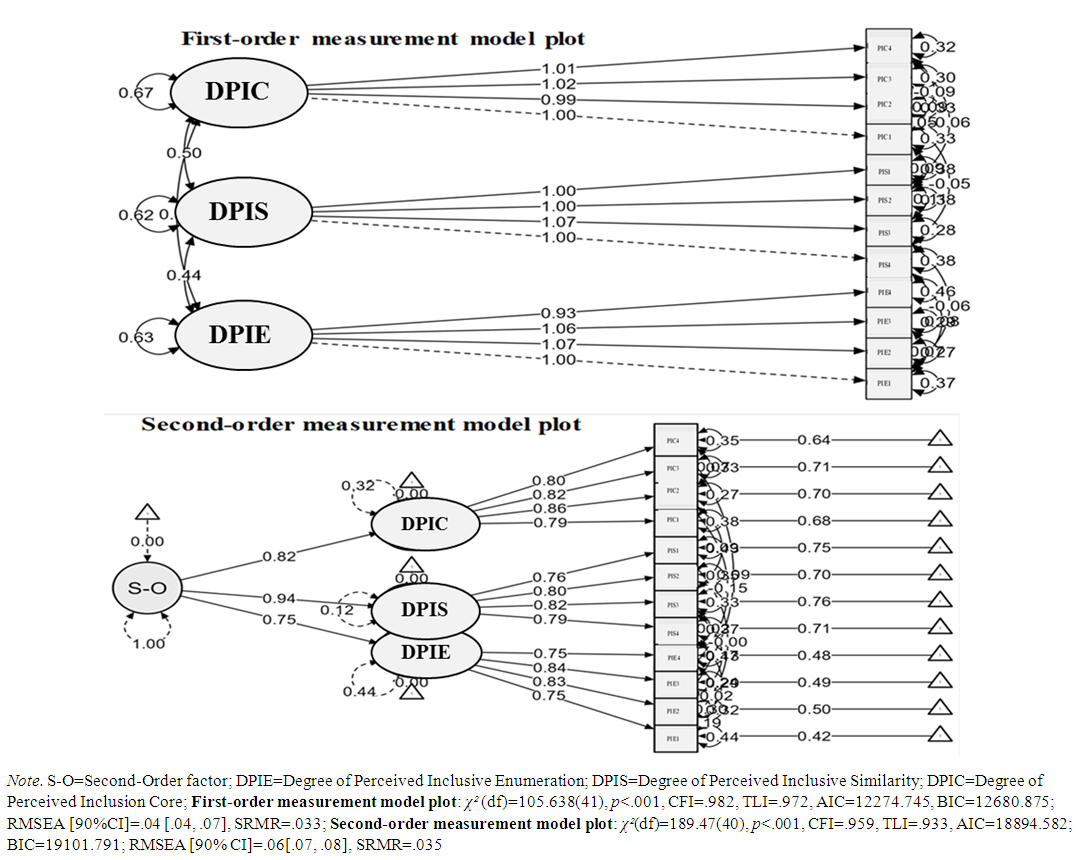

- First-order confirmatory factor analyzes report an acceptable fit of the factor structure to the empirical sample data (χ²(df)=105.638(41), p<.001, CFI=.982, TLI=.972, AIC=12274.745, BIC=12680.875; AIC/BIC=.96; RMSEA [90%CI]=.04 [.04, .07], SRMR=.033). The factor loadings reflecting the factor relationships between the manifest variables and the corresponding latent variable are acceptable (>.40). They vary between .93 and 1.07 for the DPIE, between .10 and 1.07 for the DPIS and between .99 and 1.02 for the DPIC (see Figure 2, First-order measurement model plot).

| Figure 2. First and second-order confirmatory tri-factor structures (CFA) of the Degree of Perceived Inclusion of an Outgroup Members within individuals’ Ingroups scale |

3.2.2. Measurement Equivalence Analyses of the DPIOMI by Gender (Male vs. Female)

- The configural invariance test indicates that the DPIOMI factor model presents acceptable fit indices; which guarantees that in general the three-factor DPIOMI measurement model applies to the two categories compared (χ²(df)=216.90(82), p<.001; CFI=.965, TLI=.944). In qualitative terms, this pattern is the same in men and women. The RMSEA value argues for a better fit of the configural model (RMSEA [95%CI]=.08 [.07, .09], SRMR=.04). The value of the AIC/BIC ratio is relatively low (AIC/BIC=.98), which shows that the configural model justifies an acceptable compromise between the adjustment of the model and the complexity of the model. Metric invariance compares factor loadings between groups. The results indicate that the observed variables of the tested factor model correlate positively with the latent factors. The indices saturate at 1 in both groups and the chi-square difference is not significant (Δχ²=25.37; Δdf=18; p>.05). This supports the existence of metric invariance of the DPIOMI scale. This metric model constrains a better fit (CFI=.96; TLI=.95). The RMSEA value is favorable for an excellent fit of the metric model (RMSEA [90%CI]=.07 [.06, .09], SRMR=.05). The ΔCFI is less than .01 (ΔCFI=.002<.01); which indicates a parsimonious model constrained by equality. These results support the metric invariance of the DPIOMI scale. We conclude that men and women interpret the items of this measure in the same way.The scalar invariance test is established by comparing the average structure of the metric model to that of the scalar model. Table 2 presents the factor means reflecting the means on the latent factors of the DPIOMI of the men’s group (varying between .63 and 1.50) and those of the women’s group (varying between .88 and 1.53). These average scores do not present significant differences. Likewise, the intercepts are equal between these groups (χ²(df)=242.27(123), p<.001; CFI=.96; TLI=.96). The chi-square difference is very small and not significant (Δχ²=-1.2×10-12; Δdf=23; p>.05) and the value of the AIC/BIC ratio is very low (AIC/BIC=.977). The ΔCFI difference test indicates that the scalar model is parsimonious (ΔCFI=-.006<.01). This value indicates that there is a better accommodation between the fit and the complexity of the scalar model. Thus, these two categories of heterosexuals (men and women) interpret the items of the DPIOMI scale in the same way. The Root Mean Square Error Approximation (RMSEA) better represents the adequacy of the model not only to the population of heterosexuals, but also to the sample of heterosexuals surveyed. The RMSEA value is very low, indicating a better fit of the scalar model (RMSEA [90%CI]=.06 [.05, .07], SRMR=.05]). These data support the hypothesis of scalar invariance of the validated scale. Considering all these results of structural stability of the DPIOMI scale, we conclude that this instrument presents acceptable psychometric parameters. Therefore, it can be recommended in the evaluation of DPIOMI in heterosexual males and females. The present research also ensures the construct, discriminant and predictive validities of this measure.

|

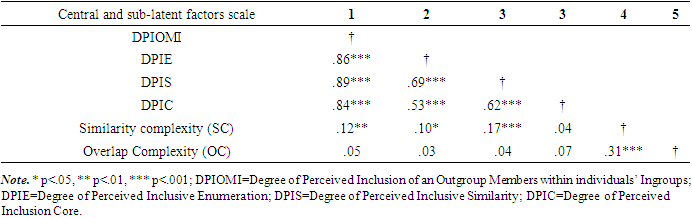

3.2.3. Test of Construct and Discriminant Validities of the DPIOMI Scale

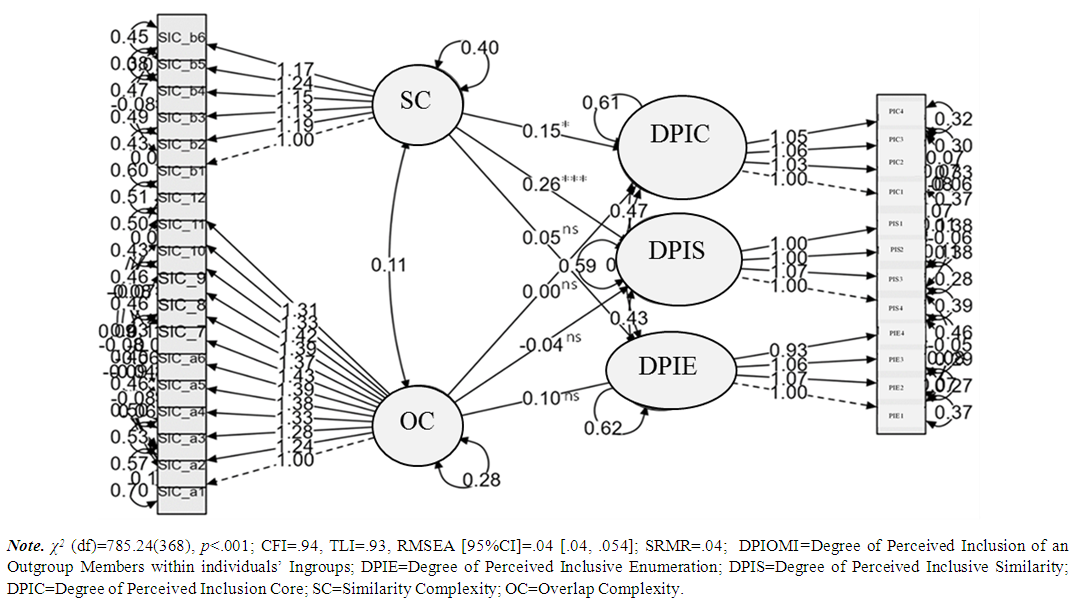

- The construct validity of the DPIOMI scale tests the idea that the three extracted latent factors (PIE, PIS, and PIC) are both positively and significantly related to each other and to the higher order factor structure (main factor DPIOMI). The correlation test indicates that the three factors extracted from the DPIOMI scale are positively and significantly correlated with each other (p<.001). These factors are positively and significantly (p<.001) related to the DPIOMI (see Table 2). This result thus supports the construct validity of this instrument as the confirmation test could report. The discriminant validity of the DPIOMI scale is ensured by providing evidence of the existence of dissimilarities via very weak or negative relationships between this instrument and SIC subscales: OC and SC (see Table 3 and Figure 3).

|

| Figure 3. Discriminant validity of the DPIOMI scale in the structural relation model |

=1.26, p>.05; 95% CI [-.05, .26]), PIS (β=-.03, SE=.07.

=1.26, p>.05; 95% CI [-.05, .26]), PIS (β=-.03, SE=.07.  =-.45, p>.05; 95% CI [-.19, .11]) and PIC (β=.00, SE=.08,

=-.45, p>.05; 95% CI [-.19, .11]) and PIC (β=.00, SE=.08,  =.04, p>.05; 95% CI [-.15, .16]). On the other hand, the results reveal very weak and significant linear and structural relationships between SC and PIS (β=.26, SE=.07,

=.04, p>.05; 95% CI [-.15, .16]). On the other hand, the results reveal very weak and significant linear and structural relationships between SC and PIS (β=.26, SE=.07,  =3.70, p<.001; 95% CI [.12, .40]) and PIC (β=.15, SE=.07,

=3.70, p<.001; 95% CI [.12, .40]) and PIC (β=.15, SE=.07,  =2.13, p<.05; 95% CI [.01, .28]). SC is very weakly and insignificantly related to PIS (β=.05, SE=.07,

=2.13, p<.05; 95% CI [.01, .28]). SC is very weakly and insignificantly related to PIS (β=.05, SE=.07,  =.73, p>.05; 95% CI [-.08, .19]). These results provide support for the discriminant validity of the DPIOMI scale. Which means that DPIOMI scale is different from SIC.

=.73, p>.05; 95% CI [-.08, .19]). These results provide support for the discriminant validity of the DPIOMI scale. Which means that DPIOMI scale is different from SIC.3.2.4. Predictive Validity of the DPIOMI Scale: Structural Relationships between Cognitions, Intergroup Affects and DPIOMI

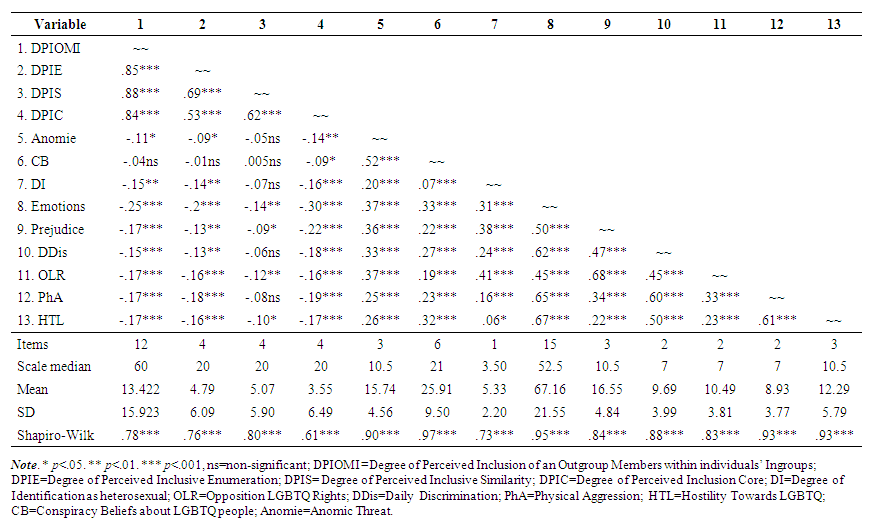

- The descriptive data (see Table 4) presents the average distributions of participants’ tendencies relating to the variables measured in the study. In the analysis, each average trend is compared to the median score of the corresponding measure. When the sample mean trend is greater than the median score of the measure, it indicates that participants exhibit the trait assessed by the measure. In fact, we observe, initially, that the average distributions of the participants on the DPIOMI scale and on its dimensions are lower than the corresponding median scores. Their trend on the general DPIOMI is very weak compared to the median score (M=13.42

| Table 4. Preliminary Descriptive and correlational statistics |

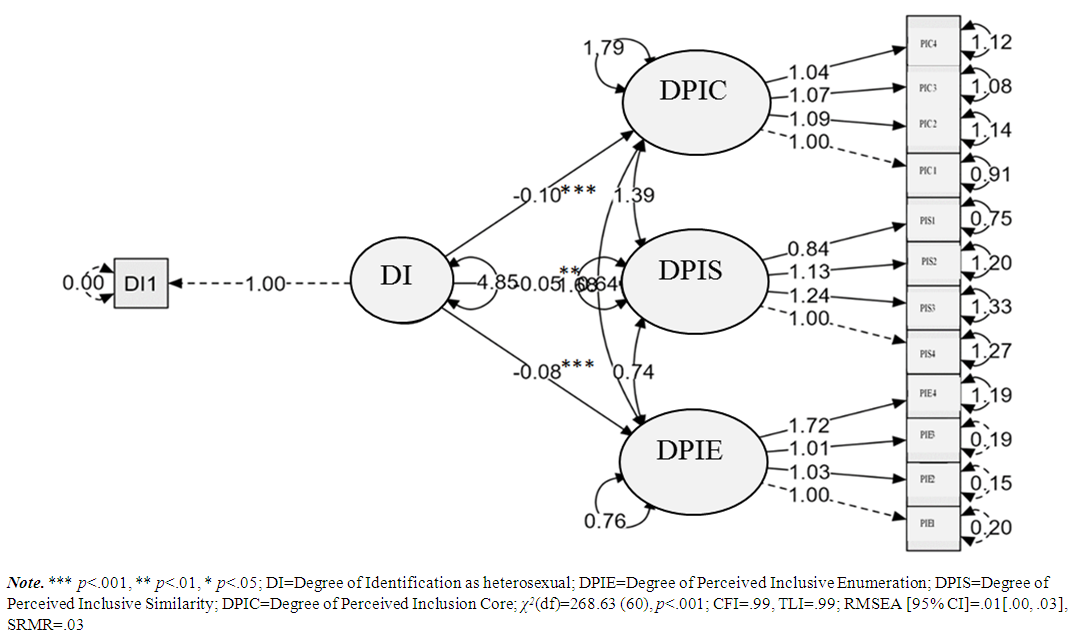

3.2.4.1. High Degree of Identification as Heterosexual as a Source of low DPIOMI

- This structural model explains the weak perceived inclusion of the identity plurality of LGBTQ people in the identity plurality of the participants, due to their strong identification as heterosexuals. Linear regression indices indicate that this strong identification explains a significant drop in DPIE (β=-.08, SE=.01,

=-4.75, p<.001; 95% CI [-.11, -.04]), DPIS (β=-.05, SE=.01,

=-4.75, p<.001; 95% CI [-.11, -.04]), DPIS (β=-.05, SE=.01,  =-2.62, p<.01; 95% CI [-.08, -.01]) and DPIC (β=-.10, SE=.02,

=-2.62, p<.01; 95% CI [-.08, -.01]) and DPIC (β=-.10, SE=.02,  =-4.38, p<.001; 95% CI [-.14, -.05]). Following the logic of the PIOMI, these results support the idea that the degree of identification as heterosexual significantly reduces inclusive tolerance towards LGBTQ people.

=-4.38, p<.001; 95% CI [-.14, -.05]). Following the logic of the PIOMI, these results support the idea that the degree of identification as heterosexual significantly reduces inclusive tolerance towards LGBTQ people. | Figure 4. Model of explanation of DPIOMI by the degree of identification as heterosexual |

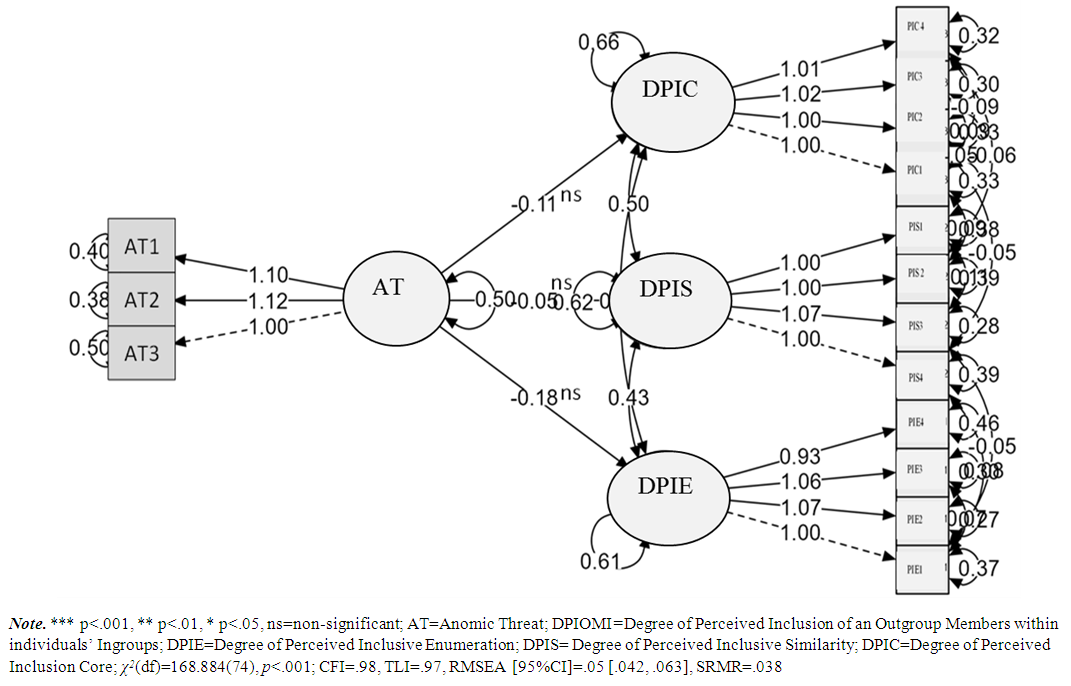

3.2.4.2. Anomic Threat as a Source of a Low DPIOMI

- The structural model in Figure 5 explains the low level of perceived inclusion of LGBTQ people in participants’ ingroups by the anomic threat they feel. Indeed, this threat is negatively associated with DPIE (β=.18, SE=.06,

=-2.89, p>.05; 95% CI [-.30, -.05]), DPIS (β= -.05, SE=.06,

=-2.89, p>.05; 95% CI [-.30, -.05]), DPIS (β= -.05, SE=.06,  =-.78, p>.05; 95% CI [-.16, .07]) and DPIC (β=-.11, SE=.06,

=-.78, p>.05; 95% CI [-.16, .07]) and DPIC (β=-.11, SE=.06,  =- 1.76, p>.05; 95% CI [-.23, .01]). From the perspective of PIOMI, these relationships indicate that the anomic threat (i.e. the disintegration as lack of trust and erosion of moral standards/deregulation as lack of legitimacy and effectiveness of leadership; Teymoori et al., 2016, 2017) represented by LGBTQ people induces low tolerance among participants towards them. The related model presents a better fit to the reality of the heteronormative context (χ2(df)=168.88(74), p<.001; CFI=.98, TLI=.97, RMSEA [95%CI]=.05 [.04, .06], SRMR=.03).

=- 1.76, p>.05; 95% CI [-.23, .01]). From the perspective of PIOMI, these relationships indicate that the anomic threat (i.e. the disintegration as lack of trust and erosion of moral standards/deregulation as lack of legitimacy and effectiveness of leadership; Teymoori et al., 2016, 2017) represented by LGBTQ people induces low tolerance among participants towards them. The related model presents a better fit to the reality of the heteronormative context (χ2(df)=168.88(74), p<.001; CFI=.98, TLI=.97, RMSEA [95%CI]=.05 [.04, .06], SRMR=.03). | Figure 5. Model of explanation of DPIOMI by anomic threat |

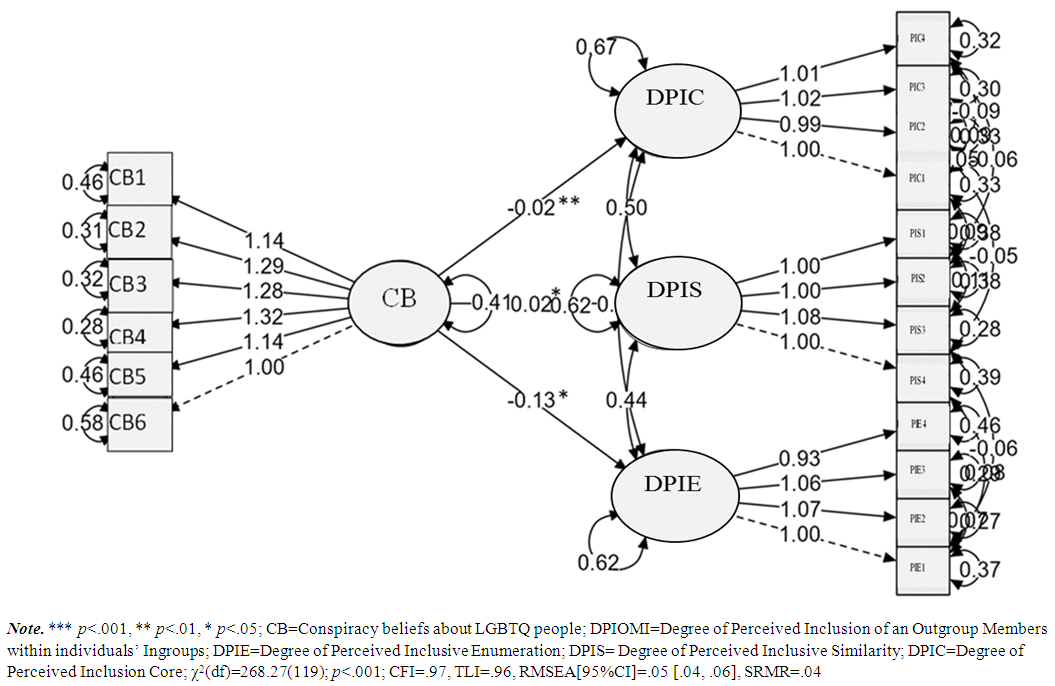

3.2.4.3. Conspiracy Beliefs about LGBTQ People as a Predictor of a Low DPIOMI

- The results of the model in Figure 6 report that participants’ belief in the existence of an LGBTQ conspiracy explains the low perceived inclusion of the socio-identity plurality of LGBTQ people in their socio-identity plurality. This model adequately fits the data from the highly heteronormative context (χ2(df)=268.27(119); p<.001; CFI=.97, TLI=.96, RMSEA[95%CI]=.05 [.04, .06], SRMR=.04). We observe weak regression coefficients indicating that conspiracy beliefs are a significant inhibitory factor of DPIE (β=-.13, SE=.06,

=-2.10, p<.05, 95% CI[-.26, -.00]), DPIC (β=-.02, SE=.06,

=-2.10, p<.05, 95% CI[-.26, -.00]), DPIC (β=-.02, SE=.06,  =-.37, p<.01, 95% CI [-.15, .10]) and DPIS (β=.01, SE=.06,

=-.37, p<.01, 95% CI [-.15, .10]) and DPIS (β=.01, SE=.06,  =.27, p<.05, 95% CI[-.10, .13]).

=.27, p<.05, 95% CI[-.10, .13]). | Figure 6. Structural model of the prediction of a low DPIOMI by conspiracy beliefs about LGBTQ people |

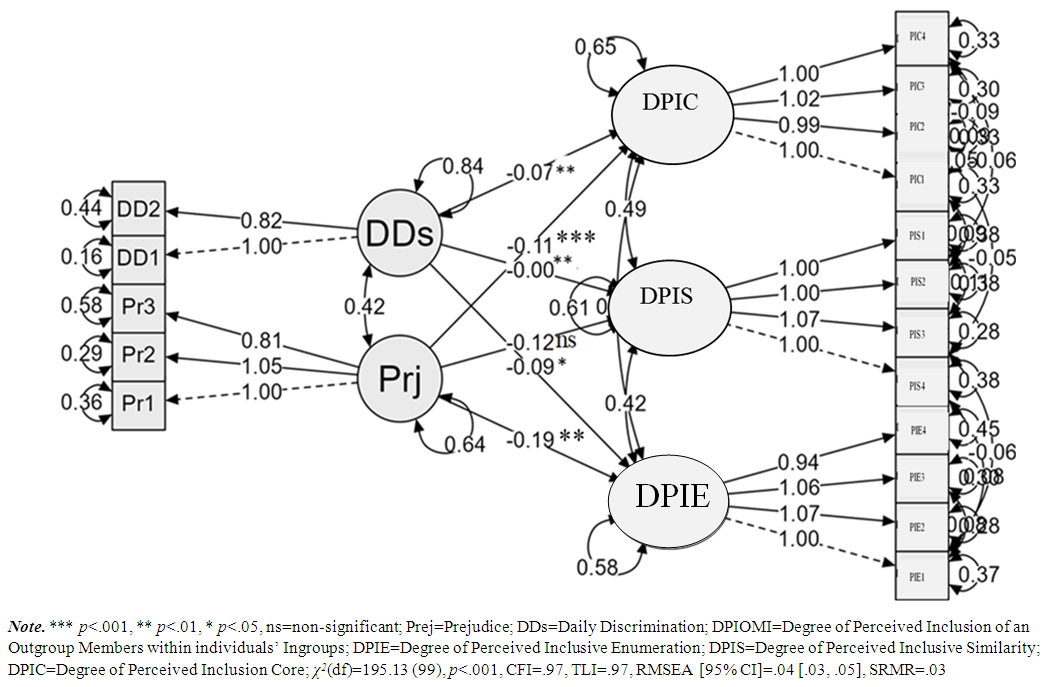

3.2.4.4. Prejudice and Daily Discrimination as Predictors of a Low DPIOMI

- Prejudice and everyday discrimination against LGBTQ people non-significantly explains their low inclusion in participants’ ingroups, as indicated by the model data in Figure 7, which adequately fits the context of the study (χ2(df)=195.13 (99), p<.001, CFI=.97, TLI=.97, RMSEA [95% CI]=.04 [.03, .05], SRMR=.031). Indeed, prejudice against LGBTQ people contributes to very strong intolerance towards them. They are negatively and significantly related to DPIE (β=-.19, SE=.06,

=-2.82, p<.01, 95% CI [-.32, -.059]) and DPIC (β=-.11, SE=.07,

=-2.82, p<.01, 95% CI [-.32, -.059]) and DPIC (β=-.11, SE=.07,  =-1.63, p<.001, 95% CI [-.25, .02]). They are, on the other hand, negatively and not significantly associated with DPIS (β=-.11, SE=.06,

=-1.63, p<.001, 95% CI [-.25, .02]). They are, on the other hand, negatively and not significantly associated with DPIS (β=-.11, SE=.06,  =-1.74, p>.05, 95% CI [-.25, .01]). Daily discrimination against LGBTQ people also significantly explains DPIOMI. Indeed, the relationship model establishes that daily discrimination of LGBTQ people significantly explains low DPIE (β=-.07, SE=.06,

=-1.74, p>.05, 95% CI [-.25, .01]). Daily discrimination against LGBTQ people also significantly explains DPIOMI. Indeed, the relationship model establishes that daily discrimination of LGBTQ people significantly explains low DPIE (β=-.07, SE=.06,  =-1.23, p<.01, 95% CI [-.19, .04]), low DPIS (β=-.003, SE=.05,

=-1.23, p<.01, 95% CI [-.19, .04]), low DPIS (β=-.003, SE=.05,  =-.05, p<.01, 95% CI [-.11, .11]) and low DPIC (β=-.09, SE=.05, Ⱬ=-1.57, p<.01, 95% CI [-.20, .02]).

=-.05, p<.01, 95% CI [-.11, .11]) and low DPIC (β=-.09, SE=.05, Ⱬ=-1.57, p<.01, 95% CI [-.20, .02]).  | Figure 7. Predicting model of a low DPIOMI by prejudices and daily discrimination of LGBTQ people |

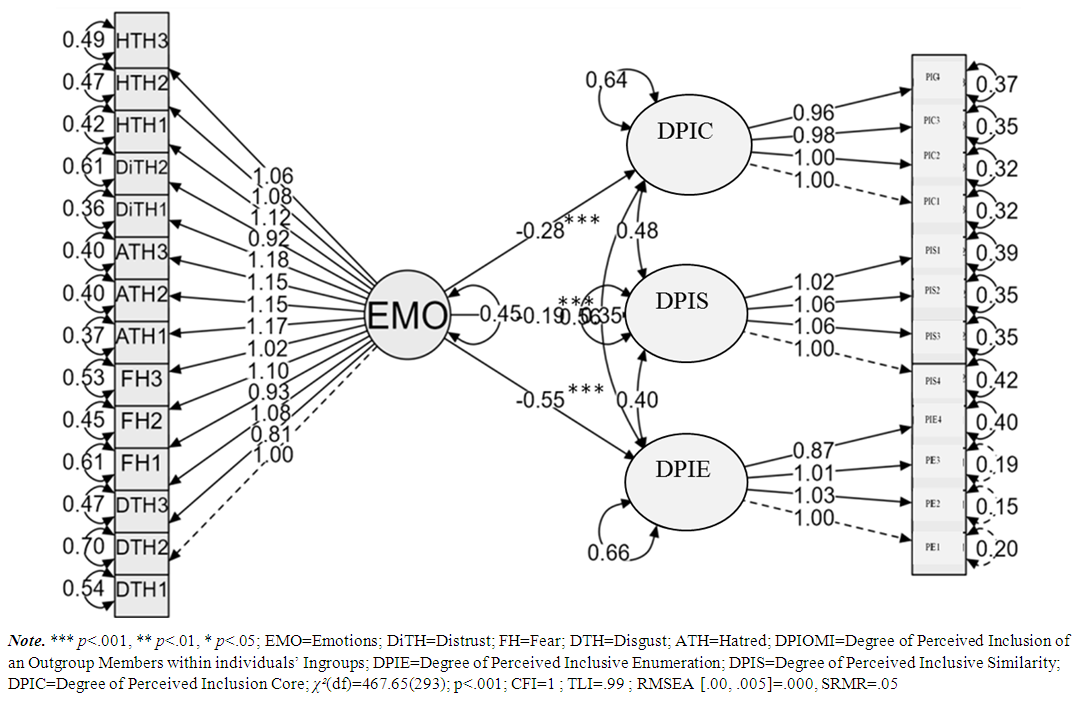

3.2.4.5. Negative Emotions towards LGBTQ People as a Source of a Low DPIOMI

- The structural relationships of the model in Figure 8 indicate that negative emotions significantly induce a very low inclusion of the socio-identity plurality of LGBTQ people in the socio-identity plurality of the participants, as evidenced by the regression coefficients. Indeed, emotions significantly explain a low DPIE (β=-.54, SE=.03,

=-18.12, p<.001; 95% CI [-.60, -.48]), a low DPIS (β=-.19, SE=.01,

=-18.12, p<.001; 95% CI [-.60, -.48]), a low DPIS (β=-.19, SE=.01,  =-11.94, p<.001; 95% CI [-.22, -.16]) and a low DPIC (β=-.27, SE=.01,

=-11.94, p<.001; 95% CI [-.22, -.16]) and a low DPIC (β=-.27, SE=.01,  =-14.27, p<.001; 95% CI [-.31, -.23]). By relating each emotion to the overall DPIOMI, the results report that each emotion significantly predicted low DPIOMI. Concretely, we note negative and significant relationships between DPIOMI and fear (β=-.17, p<.001), distrust (β=-.20, p<.001), disgust (β=-.14, p<.01), anger (β=-.21, p<.001) and hatred (β=-.31, p<.001) towards LGBTQ people. We conclude that their exclusion from the participants’ ingroups is explained by the negative emotions felt towards them.

=-14.27, p<.001; 95% CI [-.31, -.23]). By relating each emotion to the overall DPIOMI, the results report that each emotion significantly predicted low DPIOMI. Concretely, we note negative and significant relationships between DPIOMI and fear (β=-.17, p<.001), distrust (β=-.20, p<.001), disgust (β=-.14, p<.01), anger (β=-.21, p<.001) and hatred (β=-.31, p<.001) towards LGBTQ people. We conclude that their exclusion from the participants’ ingroups is explained by the negative emotions felt towards them.  | Figure 8. Negative emotions as predictors of a low DPIOMI |

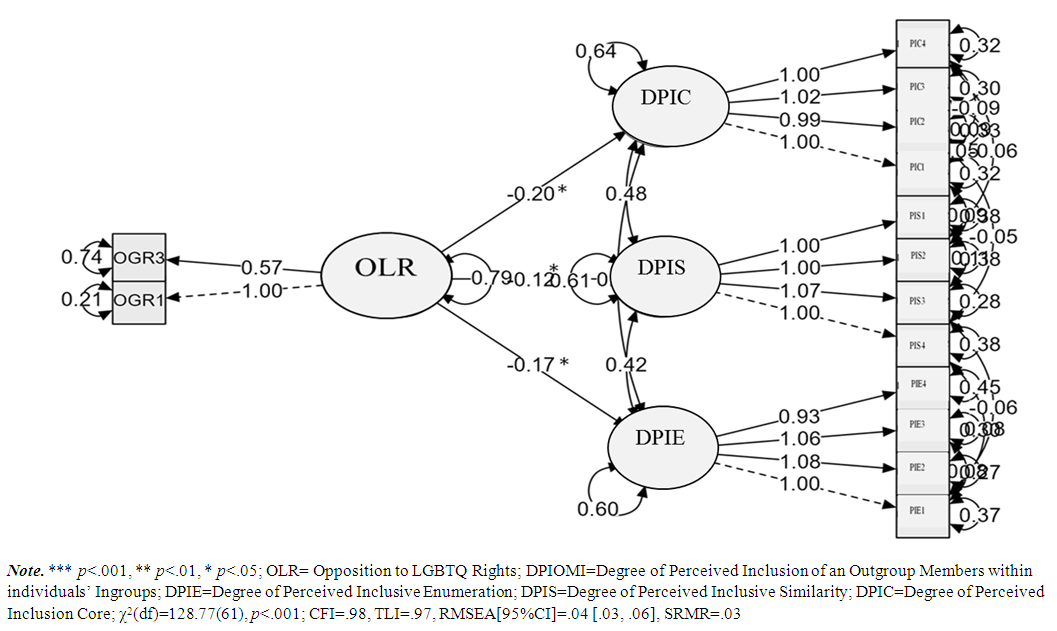

3.2.4.6. Opposition to LGBTQ Rights as an Explanation of a Low DPIOMI

- This model presents a very good level of fit (χ2(df)= 128.77(61), p<.001; CFI=.98, TLI=.97, RMSEA[95%CI]=.04 [.03, . 06], SRMR=.03) and reports significant asymmetric relationships between opposition to LGBTQ rights and the DPIE (β=-.171, SE=.07,

=-2.36, p<.05, 95% CI [-.31, -.03]), DPIS (β=-.12, SE=.06,

=-2.36, p<.05, 95% CI [-.31, -.03]), DPIS (β=-.12, SE=.06,  =-1.99, p<.05; 95% CI [-.24, -.002]) and DPIC (β=-.20, SE=.08,

=-1.99, p<.05; 95% CI [-.24, -.002]) and DPIC (β=-.20, SE=.08,  =-2.54, p<.05; 95% CI [-.363. -.04]). We therefore observe that the low perceived inclusion of the socio-identity plurality of LGBTQ people in the socio-identity plurality of the heterosexual ingroup results from the contestation of the rights of LGBTQ people.

=-2.54, p<.05; 95% CI [-.363. -.04]). We therefore observe that the low perceived inclusion of the socio-identity plurality of LGBTQ people in the socio-identity plurality of the heterosexual ingroup results from the contestation of the rights of LGBTQ people. | Figure 9. Path relation between opposition to LGBTQ rights and DPIOMI |

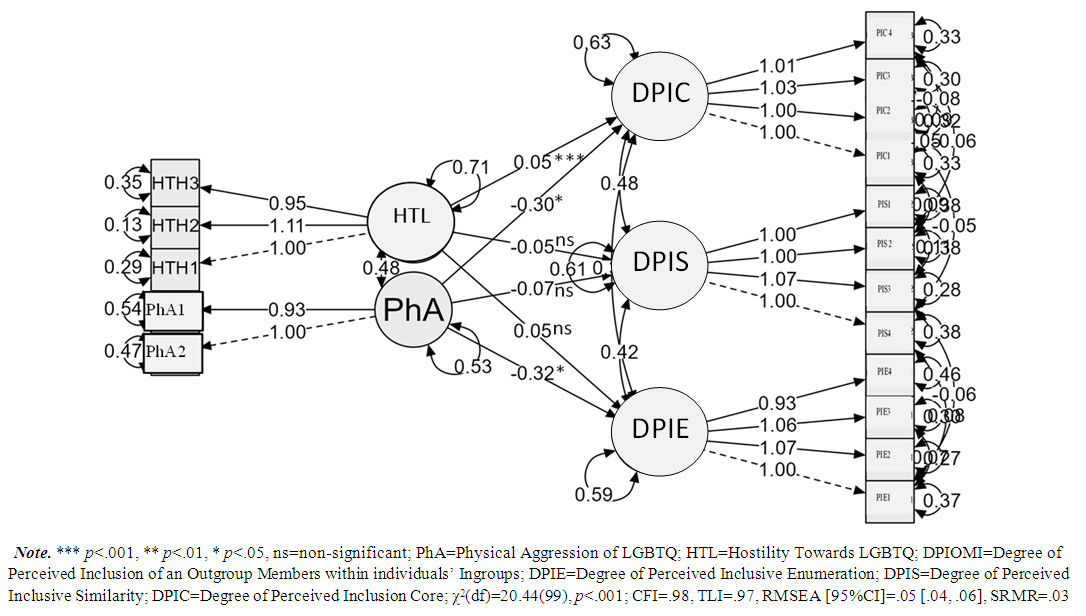

3.2.4.7. Physical Aggression and Hostility towards LGBTQ People as Predictors of a Low DPIOMI

- This model reports that the exclusion of LGBTQ people from participants’ ingroups is predicted by participants’ hostility and aggressive tendencies towards these people. Indeed, the explanatory model (see Figure 10) of the DPIOMI indicates that hostility towards LGBTQ people is negatively and significantly related to the DPIC (β=.05, SE=.11,

=.44, p<.001; 95% CI [-.17, .27]). It correlates negatively and not significantly with the DPIE (β=.05, SE=.11,

=.44, p<.001; 95% CI [-.17, .27]). It correlates negatively and not significantly with the DPIE (β=.05, SE=.11,  =.46, p>.05; 95% CI [-.16, .27]) and negatively and not significantly with the DPIS (β=-.05, SE=.10,

=.46, p>.05; 95% CI [-.16, .27]) and negatively and not significantly with the DPIS (β=-.05, SE=.10,  =-.49, p>.05; 95% CI [-.26, .15]). We also note that physical aggression has a negative and significant link with the DPIE (β=-.32, SE=.145,

=-.49, p>.05; 95% CI [-.26, .15]). We also note that physical aggression has a negative and significant link with the DPIE (β=-.32, SE=.145,  =-2.21, p<.05; 95% CI [-.60, -.03]) and the DPIC (β=-.30, SE=.145,

=-2.21, p<.05; 95% CI [-.60, -.03]) and the DPIC (β=-.30, SE=.145,  =-2.10, p<.05; 95% CI [-.58, -.02]). On the other hand, we note that there is a non-significant negative relationship between physical aggression of LGBTQ people and the DPIS (β=-.07, SE=.13,

=-2.10, p<.05; 95% CI [-.58, -.02]). On the other hand, we note that there is a non-significant negative relationship between physical aggression of LGBTQ people and the DPIS (β=-.07, SE=.13,  =-.54, p>.05; 95 % CI [-.34, .19]). We conclude that the DPIS is not significantly related to intergroup hostility and physical aggression. These two factors significantly induce a low DPIC. In short, hostility and physical aggression towards LGBTQ people significantly induce a low perceived inclusion of their multiple identities in the multiple identities of the participants.

=-.54, p>.05; 95 % CI [-.34, .19]). We conclude that the DPIS is not significantly related to intergroup hostility and physical aggression. These two factors significantly induce a low DPIC. In short, hostility and physical aggression towards LGBTQ people significantly induce a low perceived inclusion of their multiple identities in the multiple identities of the participants.  | Figure 10. Hostility and physical aggression as predictors of a low DPIOMI |

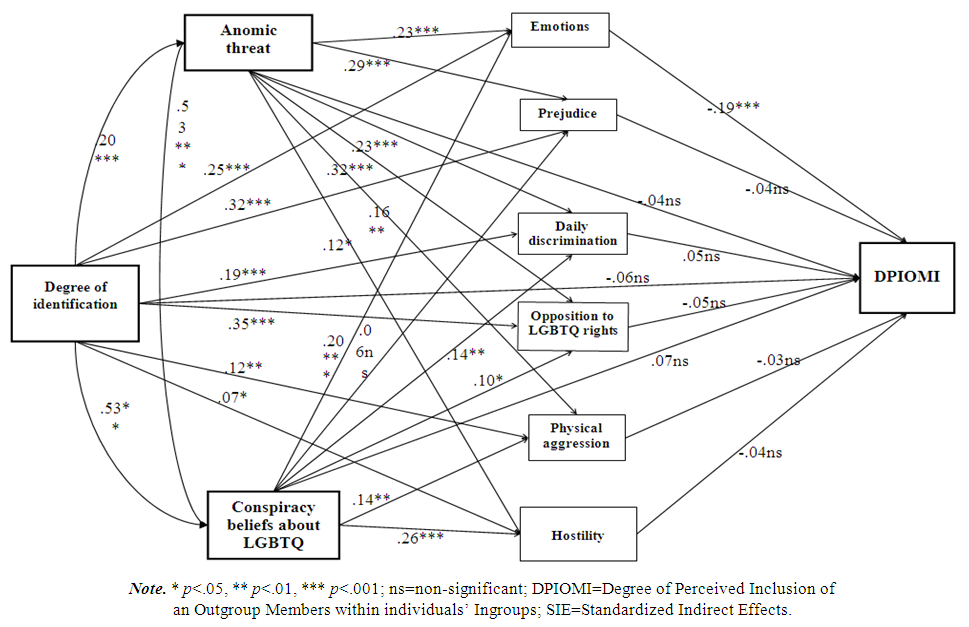

3.3. DPIOMI Structural and Summary Models

- The model in Figure 11 makes it possible to analyze the impact of intergroup cognitions and affects towards LGBTQ people on the DPIOMI of heterosexuals in a highly heteronormative context. It mainly links identification as heterosexual to DPIOMI through a double mediation ensured firstly by anomic threat and conspiracy beliefs (see Dzuetso Mouafo et al., 2023) and secondly by intergroup emotions, prejudices, daily discrimination of LGBTQ people, opposition to their rights, and hostility and physical aggression against them. In fact, the results report that the identification of participants as heterosexual is negatively and not significantly linked to DPIOMI (β=-.06, ns). This identification positively and significantly induces anomic threat (β=.20, p<.001) and conspiracy beliefs (β=.53, p<.01).

| Figure 11. General explanatory model of the perceived inclusion of LGBTQ minorities in heterosexual ingroups |

| Figure 12. Summary model of the perceived inclusion of the outgroup members (LGBTQ) in the participants’ (heterosexuals) ingroups in a highly heteronormative context |

4. Discussion