-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2024; 14(1): 1-14

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20241401.01

Received: Feb. 26, 2024; Accepted: Mar. 8, 2024; Published: Mar. 22, 2024

Collective Memory of Colonial Violence and Hostility Towards Colonial Powers in the African Context: The Moderating Role of Intergroup Cognitions

Achille Vicky Dzuetso Mouafo1, Sonia Npiane Ngongueu2, Gustave Adolphe Messanga2

1Department of Philosophy and Psychology, University of Maroua, Cameroon

2Department of Philosophy-Psychology-Sociology, University of Dschang, Cameroon

Correspondence to: Gustave Adolphe Messanga, Department of Philosophy-Psychology-Sociology, University of Dschang, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

While the general link between collective memory and intergroup hostility is relatively well documented, little is known about the effects of collective memory of colonial violence on the hostility of colonized peoples towards former colonizing powers, even if the concrete manifestations of this hostility make the news, as is the case with hostile attitudes towards France in its former African colonies for example. However, this collective memory, linked to subjugation, exploitation, humiliation, oppression and even massacres exercised by Westerners on Africans, could induce, in the latter, intergroup cognitions likely to incline them to develop hostile attitudes towards these colonial powers. This is the idea that this research explores. To test it, various measures were administered to 385 Cameroonians aged between 18 and 52 (M= 23.66, SD= 5.18). These measures addressed collective memory of colonial violence in Africa, intergroup cognitions, and hostility towards former colonial powers. The data collected provide empirical support for the hypothesis formulated. They indicate that collective memory of colonial violence is one of the sources of the tensions currently observed between colonized peoples and their former colonizers, as it is the case of France.

Keywords: Collective memory, Colonization, Hostility, Intergroup cognitions, Former colonial powers

Cite this paper: Achille Vicky Dzuetso Mouafo, Sonia Npiane Ngongueu, Gustave Adolphe Messanga, Collective Memory of Colonial Violence and Hostility Towards Colonial Powers in the African Context: The Moderating Role of Intergroup Cognitions, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2024, pp. 1-14. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20241401.01.

1. Introduction

- Colonization is an expansionist movement that allowed European powers to impose their domination in America, Africa, and Asia (Kehinde, 2021). It is considered one of the most complex and traumatic events in human history, as it left its mark on the social relations between nations and the ideologies of all peoples (Loomba, 2005). The collective memories that citizens of colonized and colonizing countries hold about the colonial era, and particularly colonial violence, still permeate their current relationships (Volpato & Licata, 2010). Among Africans, the memory of the violent and negative aspects of the colonial past can constitute a threat to social identity and arouse representations, cognitions and blame towards the former colonizers (Baumeister & Hastings, 1997). It is undoubtedly in this logic that the hostility expressed in waves of anti-French sentiment and agitations observed today in several French-speaking African countries is situated (Endong, 2020). However, in explaining this hostility, the role of the collective memory of colonial violence remains a poorly documented aspect of the specialized literature; hence the interest of this research, which specifically assesses the impact that the cognitions developed towards colonizers, and stemming from the collective memory of colonial violence, can have on the current hostility towards former colonial powers in an African context.The Collective Memory of Colonial Violence in AfricaColonization refers to the conquest and control of the land and property of others, the forced seizure of the local economy, and the reshaping of non-capitalist economies to accelerate European capitalism (Loomba, 1998). Using various methods, including direct rule, indirect rule or Salazarist and paternalistic approaches, colonial powers (Belgium, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Portugal, or Spain notably) devastated African communities, cultures, and lands through the exploitation of natural resources, violence, and slavery (Ngozi, 2019). Most of them administered their colonies in a white supremacist logic consisting in considering Africans as barbarians or savages called, therefore, to be civilized (Delavignette, 1968; Kehinde, 2021). To achieve this end, they resorted to physical violence (use of severe punishment, force, oppression, coercion, repression, mistreatment, or slavery) and psychological violence (racist stereotypes, discrimination, intimidation of indigenous people, legitimization of domination and subordination of the native, inferiorization) (Delavignette, 1968; LeVine, 1964; Prescott, 1979). In Cameroon for example, the colonizers used brutal and violent means, as well as harsh punishments as tools of political intimidation to incite the indigenous populations, considered inferior, uncivilized, violent or infantile (Césaire, 2004), to conform to colonial requirements (Betts, 1955; LeVine, 1964; Ngando, 2006; Rubin, 1971). These elements reflect a brutal, exploitative and oppressive experience of colonization, which profoundly affected indigenous communities and left an indelible imprint on politics, economics, culture, and social norms (Fanon, 1963; Okazaki et al., 2008). Its most disastrous consequences are psychological (Utsey et al., 2015), since the populations are marked by the colonial mentality (Boahen, 1987), which translates the psychological inferiorization of the colonized, transmitted by collective memory (David & Okazaki, 2006).The social psychology of collective memory of colonization is an underexplored scientific question (Durante et al., 2010; Figueiredo et al., 2018; Licata & Klein, 2005; Volpato & Cantone, 2005). The rare existing research reports that in the African context specifically, the collective memory of colonization is associated with negative memories, because it recalls slave trade, violence, oppression, subjugation, attack on the dignity of Blacks, dehumanization, mass killings and arbitrary imprisonment. It is linked to: 1) the dehumanization of black people (alienation of their human rights, colonial exposure, degrading treatment); 2) the attack on the physical and psychological integrity of Blacks and the restriction of their freedoms (acts aimed at exploiting Blacks and acts of mutilation such as “cutting hands” and punishments such as "use of the whip", among others); 3) abuse of power (oppression and mistreatment of black people by the colonial administration, the Church or former colonizers); 4) the exploitation of Blacks and the natural resources of Africa (illegitimate use of the population, forced labor, exploitation of raw material reserves); 5) the politics of differentiation (differences in treatment between Blacks and Whites in political or social domains); and 6) bad behavior by colonizers (insults and racist remarks towards black people) (Figueiredo et al., 2018). Research suggests that it can play an important role in the quality of current relations between former colonizers and former colonized and impact their visions of future relations between Europe and Africa (Cabecinhas & Nhaga, 2008; Licata & Klein, 2005), because it affects intergroup cognitions (Messanga et al., 2021).Collective Memory of Colonial Violence and Intergroup CognitionsThe memory of traumatic events is generally embedded in collective memory and guides group cognitions and actions (Connerton, 1989). The literature reveals that the collective memory of past events, perceived as unfair, induces stereotypes and discrimination against the oppressor group (Fouka & Voth, 2019; Rozenas et al., 2017). For example, the Holocaust created an antagonistic view of Jews which, in turn, fueled anti-Semitic prejudices (Antoniou et al., 2020; Dinas et al., 2021). Collective memories are particularly powerful in cases of strong or traumatic emotional events, significant changes or when they are linked to identity (Conway, 2013; Pennebaker & Banasik, 2013). Collective memory of past conflicts (violations of principles of justice) validates stereotypes about outgroups, cultural stereotypes derive from collective memory of historical events, while collective memory and stereotypes shape the current social context (Fiske et al., 2002; Klein et al., 2012).From the perspective of colonization, a country like Cameroon experienced European domination whose memory reminds its populations of denial, alienation, devaluation, cultural degradation, fragmentation of identity and destruction of the spirit of community (Anyangwe, 2014; Edimo, 1992; Gomsu, 1982; Rodney, 1982). Indeed, the Colonizers alienated the natives from their culture and introduced a feeling of inferiority into their psychology. They also demonized their ancestral culture; pushing individuals to feel shame for their own culture (Boahen, 1987). To explain this experience, Lado (2005) asserts that White (i.e. colonizers) and Black (i.e. the colonized) remain racial categories whose symbolic and emotional charge, as well as the impact of the White man on the consciousness and attitudes of Africans, cannot be overlooked. Indeed, White people remind many Africans of the painful history of slavery, colonization, defeat, humiliation, domination, and exploitation (Figueiredo et al., 2018; Messanga et al., 2021). The history of colonization conveyed by the memory of Africans is linked to enslavement, subjugation, exploitation, humiliation and even massacres. This humiliating and disastrous memory could be the source of an emotional shock that would be reflected in the negative representations that Africans have of Westerners today. These representations fuel collective victimization and the development of hostile cognitions towards them (Jasini et al., 2017). Research on collective victimization reports that when members of a group feel victimized or that their group has been victimized in the past, they develop negative cognitions towards the oppressor group (Kauff et al., 2017; Pennekamp et al., 2007). These cognitions can be detrimental not only because they increase prejudice and stereotyping, but also because they reduce the tendency to interact with outgroup members in the future (Barlow et al., 2012; Hayward et al., 2017). However, these negative attitudes towards the outgroup seem to be an identity protection mechanism in these individuals, since they allow them to preserve the group, ensure its safety and its survival (Hirschberger & Ein-Dor, 2020). Indeed, the literature reveals that when the social identity of a group is negatively evaluated after a conflict, its members develop strategies to restore it or acquire a positive identity (Tajfel, 1978; Tajfel & Turner, 1986). These include, among others, strengthening ingroup solidarity, accentuating differences with the oppressor group, distancing, and mistrust (Hirschberger & Ein-Dor, 2020; Jones, 2006; Wohl & Brancombe, 2008).Collective Memory and Hostile Intergroup RelationsThe collective memory of a group’s past events is transferred to young people by people and institutions, in formal and informal ways (Bükün, 2014). Formally, the transfer takes place through official history books or commemorative days. On the informal level, diaries, films, letters and diaries or oral transmission are indicated (Olick & Levy, 1997; Vansina, 1985). It offers several advantages for individuals: 1) allowing them to protect and maintain the image of their groups from the past (Páez et al., 2008); 2) ensuring the sustainability of their groups (Bellelli et al., 2000); 3) ensuring the protection of the values, norms and characteristics of the group and providing its members with information on future relationships with outgroups (Olick & Robbins, 1998); and 4) including symbolic resources that enable a group to mobilize for social and political ends in current and future situations (Liu & Hilton, 2005).Collective memory fulfills several functions related to identity (Liu & Hilton, 2005). Indeed, it gives content to social identities that allow members of a group to recognize that they all belong to the same group, that it has a continuous history (Sani, 2008), and that it will continue to exist in the future. From the perspective of social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), collective memories can be used as a basis for intergroup comparison, so that representations of the group’s past can reinforce its identity. Conversely, remembering negative aspects of the group’s past can threaten social identity and elicit reactions such as legitimizing these events, minimizing them, denying them, or confronting outgroups (Baumeister & Hastings, 1997). Collective memory can be used to legitimize current ingroup actions. Indeed, portraying ingroup as a victim of past events has often been used to justify planned or ongoing actions against the outgroup perpetrators of these injustices (Devine-Wright, 2003). It therefore determines the quality of intergroup relations.The literature argues that there are many conflicts in which emotions, memory, conflicting historical narratives, and identity are catalysts (Conway, 2013). Indeed, studies on interethnic conflicts, for example, indicate that collective memory is one of the main factors that contribute both to triggering and reducing them (Páez & Liu, 2011). In general, the collective memory of conflicts can determine social attitudes towards adversaries. It can play an important role in shaping and guiding social attitudes (Sahdra & Ross, 2007). Created by past events and conflicts, it can affect the approach, intention, and perception of groups towards each other (Bar-Tal, 2007). Indeed, the perception of the past oppressor group as a permanent threat can sharpen the distrust that plays an important role in conflicts. Better still, when a group remembers the negative events and the conflicts of which it was victim in the past, it can perceive that it is still threatened today and feel the fear of facing a new situation of violence or conflict. This fear leads it to feel suspicious of outgroups (Jones, 2006). As a result, it can, in advance, confront outgroups or avoid them by considering its actions as right and legitimate (Wohl & Branscombe, 2008).The Consequences of the Collective Memory of Colonial Violence in Africa on the current Intergroup RelationsHostility between groups is a negative attitude towards other groups, consisting of enmity, denigration, and ill will (Smith, 1994). The literature offers several explanatory factors (Halpern & Weinstein, 2004), including: prejudice (Brewer, 2001); attachment (Critchfield et al., 2008); blind patriotism (Schatz et al., 1999); social dominance orientation (Pratto et al., 1994); right-wing authoritarianism (Altemeyer, 1996); intergroup contact (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2000); political extremism (Van der Valk & Wagenaar, 2010); and threat to group’s image (Rios & Ybarra, 2008). To these, the present research proposes to add the collective memory of colonial violence.Some of the literature on the long-term effects of historical traumatic events reports that the memory of such events is likely to produce conciliatory intergroup attitudes and behaviors today (Rees et al., 2013; Vollhardt & Staub, 2011; Warner et al., 2014). However, some research questions these findings (Hirschberger & Ein-Dor, 2020) and shows that these memories may contribute to creating psychological barriers to contemporary intergroup harmony (Canetti et al., 2018; Ein-Dor & Hirschberger, 2013; Lifton, 2005; Markiewicz & Sharvit, 2021; Vollhardt & Nair, 2018). For the specific case of colonization, collective memories play an important role in the formation of current relations between former colonizers and colonized. They also have an impact on their vision of future relations between Europe and Africa, for example (Cabecinhas & Nhaga, 2008; Licata & Klein, 2005). This is because when members of a group remember having been the victims of atrocities and oppression in the past, they feel emotions and take negative actions towards the oppressing group (Kauff et al., 2017).Collective victimization has a deep and lasting impact not only on the emotions and beliefs of those directly involved, but also on entire communities and even generations after the traumatic event (Bouchat et al., 2017; Hirschberger, 2018; Li et al., 2022; Volkan, 2001). In this vein, one can suggest that the feeling of historical collective victimization that Africans might experience in the face of colonial violence would be the source of the anti-Western feeling displayed by some of them. This sentiment refers to broad opposition, prejudice, or hostility toward Western people, Western culture, or Western world politics (Merriam-Webster, 2021). It is expressed through hostile cognitions and emotions towards Westerners, and everything related to them. It is fueled by anti-imperialism. This is why it mainly targets countries found guilty of colonial crimes in the past and/or present (Messanga et al., 2021). Among Africans, it results from the slave trade, colonization, racial discrimination, and exploitation of resources that their communities suffered. For them, these historical facts have generated negative representations of the White man who enslaves, subjugates, exploits, humiliates, and even kills (Lado, 2005). The French, who colonized much of West and Central Africa, are among his targets.Anti-French sentiment has increased with the creation of certain pan-African movements whose mission is to defend the nationalist cause and the fight against the hegemony of France, particularly in the countries of its former colonial empire. Their demonstrations are generally observed through anti-French protest marches in front of French embassies and in the streets (Endong, 2020). During these popular demonstrations, it often happens that French symbols (the flag for example) and companies are attacked and that French diplomats are declared persona non grata and therefore expelled from certain countries, as was the case in Mali (Khady & Bououtou-Foos, 2021). These protest actions can find their source in the feeling of victimization that stems from the collective memory of colonization in Africa, since collective memories that citizens of colonized and colonizing countries hold about the colonial era, and particularly colonial violence, still permeate their current relationships (Volpato & Licata, 2010). In this vein, recalling the violent and negative aspects of the colonial past can constitute a threat to the social identity of Africans or arouse negative representations towards the former colonizers and reactions such as revenge or blame towards the countries responsible for it (Baumeister & Hastings, 1997). We can therefore suggest that it is in this logic that the hostility expressed in waves of anti-French sentiment and agitations observed today in several French-speaking African countries is situated (Endong, 2020). However, the specialized literature does not report empirical data in support of this thesis. It therefore does not allow us to understand the possible historical roots of this phenomenon, which is gaining momentum in West African countries in particular (Guiffard, 2023), since the role of the collective memory of colonial violence in the expression of hostility towards colonizing powers remains a poorly documented subject; hence the interest of this study which proposes that the memory of colonization in general, and colonial violence in particular, which is linked to slavery, subjugation, exploitation, humiliation, massacres and even the oppression exercised by Westerners on Africans, could induce intergroup representations or cognitions among the latter, which could lead them to develop negative attitudes towards the colonial powers.Purpose of the StudyThe literature on collective memory reports that it defines the quality of current and future relationships between groups involved in a conflict in the past (Bellelli et al., 2000; Liu & Hilton, 2005; Paez et al., 2008), even if this event took place long before the birth of the current members of the said groups (Li et al., 2022). Concretely, the recall of negative events from the group’s past can threaten the social identity of its members and provoke, among them, reactions such as negation and confrontation with the perpetrator outgroup (Baumeister & Hastings 1997); hence the fact that we can consider collective memory not only as a basis for the formation and orientation of social attitudes (Sahdra & Ross, 2007), but also as a catalyst for many situations of intergroup conflict or hostility (Conway, 2013; Paez & Liu, 2011). Indeed, the representation of the ingroup as a victim of past traumatic events is sufficient to justify attacks against outgroups who are the perpetrators (Devine-Wright, 2003).It appears from the analysis of the literature that due to the fact that the collective memory of colonial violence in Africa is an underexplored scientific question, little is known about the link it could have with hostility that we are increasingly observing on the African continent towards the former colonial powers, including France in particular. Indeed, a strong hostile feeling, called anti-French sentiment, is developing in the former colonies (Khady & Bououtou-Foos, 2021), not only because of this country’s colonial past, but also because of its current neocolonial attitudes and practices that allow it to maintain a certain degree of control over the economies and political systems of its former colonies through a system nicknamed Françafrique (Andjembe Etogho et al., 2023). Thus, associated with negative memories including violence, oppression, subjugation, attack on the dignity of colonized peoples, dehumanization, large-scale massacres, arbitrary imprisonment, abuse of power, exploitation, insults and racist remarks towards colonized peoples (Durante et al., 2010; Figueiredo et al., 2018; Licata & Klein, 2005; Volpato & Cantone, 2005), colonization has the characteristics of a traumatic event that can induce the development of hostile attitudes towards former colonial powers, particularly because the reminder of the violent and negative aspects of the colonial past can constitute a threat to peoples’ social identity, arouse negative representations and provoke reactions such as revenge or blame against ex-colonizers (Baumeister & Hastings, 1997). The examination of this little-explored question constitutes not only the subject of this study, but also its main expected contribution to the specialized literature. It specifically aims to analyze the links that could exist between the collective memory of colonial violence, negative cognitions towards former colonial powers and hostility towards them. Its interest lies in the fact that it could make it possible to understand current relations between ex-colonizers and colonized people on the basis of the collective memory of certain traumatic historical events. Hypothesis The present research tests the hypothesis that: intergroup cognitions (stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination) significantly moderate the relationship between collective memory of colonial violence and hostility towards former colonial powers. Concretely, this means that in the African context, the interactions between these cognitions and the collective memory of colonial violence significantly explain the hostility towards the former colonial powers.

2. Method

- ParticipantsThe participants of this study are three hundred and eighty-five students (N= 385; 222 women, i.e. 57.7% and 163 men, i.e. 42.3%) enrolled in the Bachelor of Psychology program (274 or 71.2% in Level 1; 78 or 20.3% in Level 2; and 33 or 8.6% in Level 3) at the University of Dschang (Cameroon). They are aged between 18 and 52 years (M= 23.66, SD = 5.18). These people come from the French-speaking part of Cameroon, a former German colony, placed under the mandate of the League of Nations after the German defeat at the end of the World War I, and entrusted to the co-administration of France and Great Britain who treated it as a territory of their respective colonial empires. They freely consented to participate in the research. MaterialThe data for the present study were collected using five instruments written in the French language, all developed for the purposes of the research. Questions to collect participants’ demographic data (sex, academic level and age) were associated with it.Measure of collective memory of colonial violenceThis scale assesses the independent variable (IV) of this study. This construct refers to negative memories relating to the slave trade, violence, oppression, subjugation, as well as dehumanization, large-scale massacres, arbitrary imprisonment and attacks on the dignity of the colonized. It was developed on the basis of its indicators provided by the literature (Figueiredo et al., 2018; Wertsch, 2002), following the methodology proposed by Churchill (1979). It assesses internalized memories of colonization with 4 items (McDonald’s ω= .75; α= .74) for which the participants gave their opinion on a 7-points Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The minimum score for the overall scale is 4 (1x4 items) and the maximum score is 28 (7x4 items). The average scale score (median score) above which we can conclude that participants have the trait assessed by the scale is 14 (28/2). Factor analyses of this scale confirm its unidimensional structure with modestly acceptable structural adjustment indices (χ2= 7.91; df= 2; p<.05; CFI= .99; TLI= .98; RMSEA= .08; SRMR= .03).Measures of intergroup cognitions Three psychometric scales are used to assess cognitions towards colonial powers. They relate to the perceptual biases that the former colonized have towards the former colonizers. They are strongly inspired by the measures used in the work of Tiwari et al. (2014).Measure of prejudice against former colonial powersThis scale includes three (3) positive items (e.g. “Our former colonizers have little respect for the dignity of Africans.”). The maximum reliability saturation level of this measure is .72 (McDonald’s ω= .72; α= .72). The analysis indicates that its one-dimensional structure fits the empirical data perfectly (χ2= 818.08; df= 3; CFI= 1; TLI= 1; RMSEA= .000). The items in this measure are rated on a 7-points Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The minimum score is 3 (1x3 items) and the maximum score is 21 (7x3 items). The median of the scale (median score or threshold) above which the participants must position themselves in order to be considered as developing prejudices towards the former colonial powers is 10.50 (21/2).Measure of stereotypes towards former colonial powersThis instrument includes two (2) positive items (e.g. “Our former colonizers have a bad reputation in Africa.”; “Our former colonial powers are not honest with us.”) It is reliable (McDonald’s ω= .71, α= .71). But, due to its two-item structure, it does not benefit from a confirmatory test of its factor structure. The items in this measure are rated with a 7-points Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The minimum score is 2 (1x2 items) and the maximum score is 14 (7x2 items). The mean of the scale (median score) above which the participant must be in order to be said to adhere to the stereotypes towards the former colonial powers is 7 (14/2).Measure of the tendency to discriminate against former colonial powersIt includes two (2) right-coded items (e.g. “We must also treat our former colonizers unfairly.”; “The former colonial powers are not superior to African nations.”). The reliability measures of this scale are valid (McDonald’s ω= .80, α= .80). Its confirmatory factorial structure is not established due to the reduced number of its items, evaluated with a 7-points Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The minimum score of this scale is 2 (1x2 items) and the maximum score is 14 (7x2 items). The average score of the scale (median score) above which the participant must be in order to be said to have a tendency to discriminate against former colonial powers is 7 (14/2). Measure of hostility towards former colonial powersThis measure has two (2) items. While the first is a counter-trait item (e.g. “I would like to meet our former colonizers)”, the latter is pro-trait (e.g., “I would like to take revenge on our former colonizers.”). Measures of the reliability of this measure indicate good indices (McDonald’s ω= .72, α= .72). A 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) is associated with this instrument to allow participants to express their opinions. The minimum score is 2 (1x2 items) and the maximum score is 14 (7x2 items). After recoding the reversed item scores, the average scale score (median score) at above which the participant must be located in order to be said to develop hostility towards the former colonial powers is 7 (14/2).Administration and procedure for filling questionnairesThe participants were met individually in the lecture halls of the University of Dschang. After presenting the objective of the study to them, they all agreed to participate voluntarily in the study. Their task was to carefully read and complete the self-administered questionnaires. They had to honestly express their point of view by checking a single number corresponding to their support or not for the trait assessed by each item. The duration of completing the questionnaire was approximately 15 minutes. From the point of view of research ethics, guarantees were given to them regarding the use that would be made of the information they provided as part of the study.Data analysis procedureAt the end of the survey, 393 participants were registered. Among them, 5 had completed the questionnaire to 40% and 3 had completed it to 95%. During data processing, the management of missing data was not done following the techniques for managing missing data present in the SPSS editor (the replacement of missing data by the mean of the series or by the mean of the midpoints, by linear interpolation for example), for reasons of objectivity. Therefore, due to missing data on the scales they completed, the data produced by these participants were deleted from the database. Subsequently, the data were inserted into the SPSS.27 editor. The analysis was carried out using SPSS.27 and SPSS-AMOS.23 software. The first served as a tool for descriptive statistics (Mean, standard deviation, range, minimum, maximum, and Shapiro-Wilk normality test) and correlation indices (r, p-value). The second made it possible to schematize and evaluate the moderation relationship between the collective memory of colonial violence (IV) and intergroup hostility (DV) by intergroup cognitions towards the former colonial powers (MV). Thus, the statistical indices indicating the levels of relationships between these latent variables (IV and DV) were estimated by applying the structural equation method under SPSS-AMOS.To test the hypothesis formulated, the data were processed using the SPSS.27 statistical software. A multiple linear regression test was performed. The independent variable (collective memory of colonial violence) and each moderating variable (stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination against former colonial powers) were introduced into the model. They were treated by creating an interaction effect between the independent variable and each moderating variable. It was expected from these analyses that these interaction effects would be statistically significant so that each cognition moderates the relationship between the collective memory of colonial violence and hostility towards the former colonial powers. Thus, the combinations of stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination with collective memory of colonial violence were expected to interact positively and significantly on hostility towards former colonial powers in order to indicate the expected moderating effects. The statistical indicators of these interaction effects (or moderators) are coefficients of the multiple regression model (R2 change and p-value F change, B, β(t), p-value and 95% CI).

3. Results

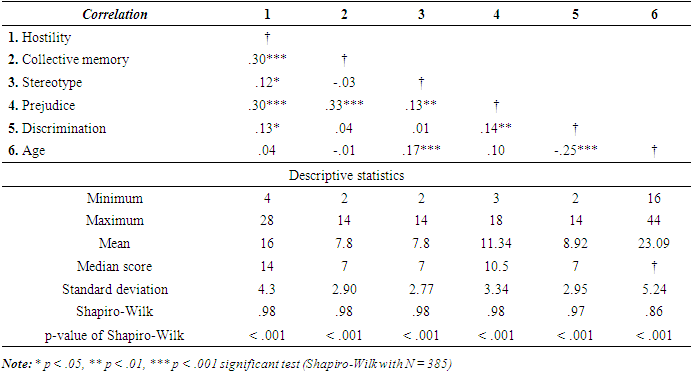

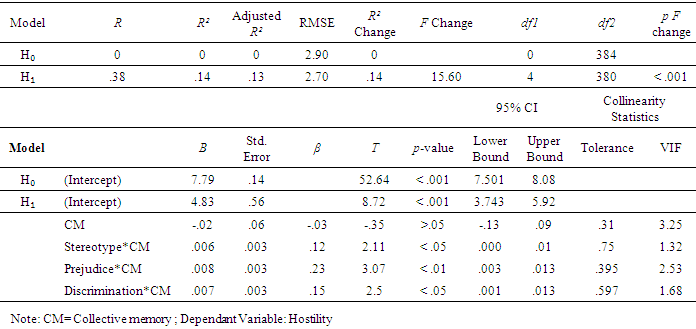

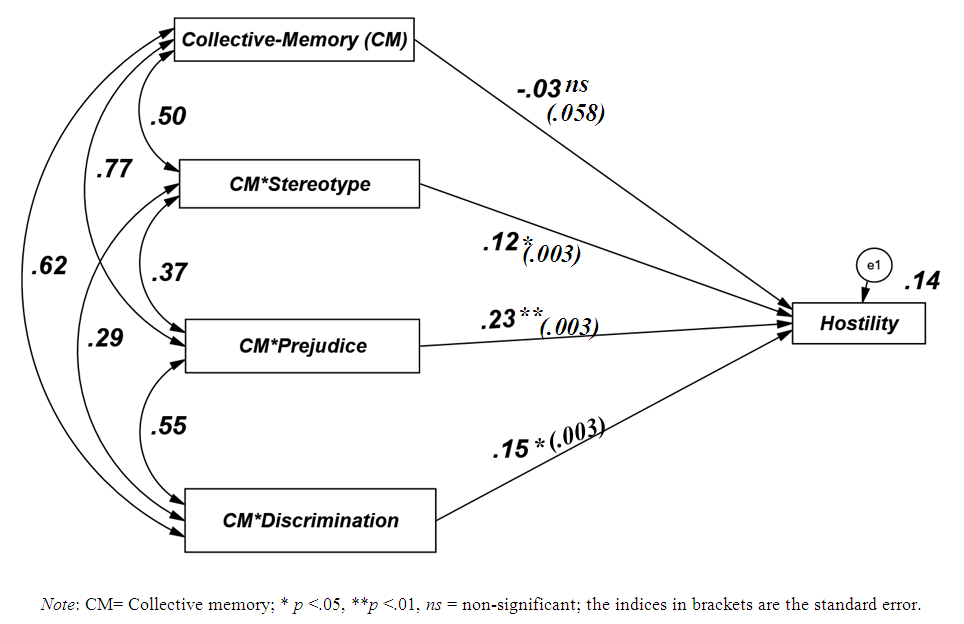

- The results are presented in two phases. The first analyses descriptive statistics and relationships between variables (See Table 1). The reading of the trends for the measured variables is made according to the median scores reflecting the average level/threshold from which the characteristic evaluated by the corresponding measure is considered to be present. The second tests the research hypothesis using multiple regression analyses interacting the independent and moderating variables (See Figure 1 and Table 2). Preliminary descriptive and correlational analyses The descriptive results indicate that for all variables, the trends are located above the median scores (See Table 1). Correlational data indicate that hostility towards former colonial powers is positively and significantly related (See Table 1) to collective memory of colonial violence (p<.001) and to intergroup cognitions towards former colonial powers (stereotypes (p<.05), prejudice (p<.001) and discrimination (p<.05)). These cognitions are in turn linked to the collective memory of colonial violence. Stereotypes and discrimination are non-significantly (p>.05) linked to the collective memory of colonial violence, while the latter is significantly (p<.001) associated with prejudice against former colonial powers.

|

|

| Figure 1. Model of interaction between collective memory and intergroup cognitions and their effects on hostility towards colonial powers |

4. Discussion

- The aim of this research was to assess the impact of collective memory of colonial violence on current hostility towards former colonial powers in an African context, considering the possible moderating role of cognitions developed towards these colonizers. It tested the hypothesis that intergroup cognitions moderate the link between collective memory of colonial violence and hostility towards former colonial powers. Concretely, the stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination generated by collective memory of colonial violence, which is linked to slavery, subjugation, exploitation, humiliation, oppression and even massacres of Africans, lead them to develop hostility towards the former colonial powers. Empirical observations lend support to this prediction. Indeed, the multiple regression analyses carried out on the collected data revealed that intergroup cognitions, considered as a categorical moderating variable, increased the link between collective memory of colonial violence and hostility towards former colonial powers. Thus, the reminder of the violation of human rights, the exploitation of the natural resources of countries, cultural losses (non-maintenance of the culture of origin), dehumanization, attacks on physical and psychological integrity (Bourhis et al., 2010; Figueiredo et al., 2018) of which Africans were victims during colonization generates, in the latter, cognitions that lead to hostile relations with the former colonial powers.This study provides empirical support for the idea that the collective memory of past conflicts influences the development of hostile attitudes towards oppressive groups in three ways (Páez & Liu, 2015). First, collective memory generates current hostile relationships by influencing categorization processes such as strengthening the intensity of in-group identification, increasing the perceived dissimilarity between in-group and out-group beliefs, stereotyping and outgroup aggression (Messick & Smith, 2002). Indeed, the activation of categorization generates prejudice and intergroup discrimination, thus promoting intergroup hostility (Abrams & Hogg, 1988; Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Second, the collective memory of past conflicts plays a cognitive-perceptual role in shaping the perception of interest, threat, and intentions of others (Bar-Tal, 2007). Perceived or actual threat is an important factor in conflict. Indeed, when groups recall past conflicts, they often perceive their current security as threatened and may even fear extinction through violence or assimilation. Such fear inevitably destroys any trust the group might have in the outgroup, and therefore even the conciliatory gestures of the said group can be misinterpreted as threatening. Third, the collective memory of past conflicts has a motivating function for collective behavior, as it stimulates groups to act collectively and justifies retaliatory actions against the outgroup (Liu & Hilton, 2005). Fear related to past threat and anger stemming from the resurgence of past atrocities motivate individuals to fight historical enemies and justify preemptive defensive action to eliminate the danger. This preventive action performs two essential functions: the protection of the group already victimized against possible conflicts and the recognition of its victimization by potential aggressor groups (Bilali & Vollhardt, 2019).The results of this research also report that intergroup cognitions (prejudices, stereotypes, and discrimination) have an impact on the link between collective memory of colonial violence and hostility towards former colonial powers. Indeed, the painful memory of colonization predisposes to prejudices, stereotypes, and discrimination against the colonial powers. It leads to the perception of threat (Bar-Tal, 2007) and this reinforces intergroup prejudices, negative stereotypes and leads to discrimination and opposition to pro-outgroup policies (Ramos-Oliveira & Pankalla, 2019; Renfro et al., 2006). Thus, the negative attitudes of Africans towards the former colonial powers are explained by the fact that the latter pose a threat to their physical and psychological well-being. In this sense, Aberson (2015) asserts that past experiences, positive and negative, predict the affective dimensions of prejudice, while only negative experiences explain the cognitive dimensions of prejudice such as stereotypes, which have long been associated with negative attitudes towards the outgroup (Spencer-Rodgers & McGovern, 2002). It is in this logic that the hostile intergroup reactions manifested by Africans in the face of the former colonial powers are situated. We then understand that the hostility expressed here stems from the memory of oppression, exploitation, large-scale massacres, and dehumanization. Indeed, in their current relations, Africans treat former colonial powers with suspicion because they still represent a danger or a threat to them (Messanga et al., 2021). This is the source of negative attitudes towards this oppressive group (Renfro et al., 2006). This is particularly the case of France. In a broader sense, the results of this research can contribute to the understanding of the rise of anti-French movements observed in several African countries today. According to Endong (2020), the presence of France has remained dominant if not preeminent in French-speaking Africa. As a result, its involvement or interference in the affairs of its former colonies is no longer appreciated by many Africans. It is for this reason that we have witnessed waves of anti-French demonstrations in several African countries in recent years (Khady & Bououtou-Foos, 2021). These rebel against corruption, violation of human rights and constitutions, France’s stranglehold in all areas of social life in their countries, neocolonialism, retrograde discourse towards Africa, monetary imperialism, support for tyrants, but above all the prevalence of French interests in Africa (Canac & Garcia-Contreras, 2011; Sylla, 2017; Yohannes, 2019). The anti-French sentiment and the demands made by Africans today are based on the need to revise the fundamentals of the relationship between France and its former colonies, so that it is beneficial to both parties (Mbembe, 2021). Although this sentiment has deep roots in French-speaking African countries, due to colonial ties, it has evolved significantly since 2013, after the intervention of French security forces in northern Mali (Exx Africa, 2020; Roger, 2019). It is further fueled, on the one hand, by the fact that the independence of the countries of French-speaking Africa is considered a fiction, in particular because their governing authorities owe their positions to France and not to the will of their peoples, and by the belief in the continuation of French colonization in Africa, on the other hand (Endong, 2020; Khady & Bououtou-Foos, 2021; Soumaré & Konan, 2019). Thus, for many Africans, the fight against neocolonialism in their country goes inextricably through the manifestation of Francophobic sentiment (Endong, 2020).The hostility shown today by Africans towards France, a dominant foreign power, has also been observed before in anti-Americanism (Endong, 2020). Whether subtle or obvious, foreign domination has hardly, if ever, been welcomed in countries around the world. Nations have always developed the instinct and the reflex to denounce and resist any form of external domination, especially when this domination becomes politically, economically and/or culturally asphyxiating. In France, for example, the government has resisted both softly and aggressively American cultural and ideological domination. France has done this by sometimes even resorting to anti-Americanism. Indeed, it perceived American cultural and ideological domination as a threat to its own culture and as an evil to be fought vigorously. Along the same lines, many of its former colonies perceived its presence and domination as a situation to be resolved with anti-French sentiment; hence the fact that growing and perceptible waves of Francophobic sentiment have prevailed since the period of decolonization in many French-speaking African countries (Roger, 2019; Soumare & Konan 2019).Implications for Research and PracticeThe results of this research report that collective memory of colonial violence generates, among the former colonized, the development of stereotypes, prejudices, and discrimination which, in turn, lead to hostility towards the former colonial powers. This study provides insight into the psychological processes linking past collective trauma to current intergroup conflict. In a broader context, it allows us to understand that the hostility arising from the collective memory of colonial violence promotes the victim groups’ well-being by playing a protective role for their identity and serves as a regulator of international relations. Indeed, the collective memory of this violent event influences diplomatic contacts between formerly colonized countries and their former colonizers, the latter being frequently suspected of carrying out neo-colonialist policies. In this vein, the literature reveals that groups that have survived extreme violence tend to view current intergroup conflict as a continuation of historical trauma and are highly suspicious of outgroups (Hirschberger & Ein-Dor, 2020). Following this logic, one can wonder if the fact that the French (target for negative colonial memories) continue with neocolonialist strategies in Africa could contribute to the perpetuation of negative collective memories towards them and fuel the hostility of which they are the victims and who’s most visible manifestations are currently observed in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger notably.Limitations and Future DirectionsAlthough this study adds value to the literature, it has a few limitations that should be noted. First, the sample of the study did not include English-speaking, Spanish-speaking, or Portuguese-speaking African populations, who suffered other forms of colonization; hence the possible problems of inferring these results to these populations. Second, this research did not assess identity threat, which is a variable closely linked to collective memory of violent events (Conway, 2013; Liu & Hilton, 2005; Pennebaker & Banasik, 2013). Thus, future research should extend these investigations to individuals who have undergone other forms of colonization than French colonization. Indeed, the latter, having rather been colonized by the British, the Spanish or the Portuguese, could have different postures from those of French-speaking populations towards their former colonizers, due to the fact that the other colonizing powers are not as strongly involved in neocolonialism as France in Africa. Other studies could also integrate the level of identity threat felt by members of groups who have been victims of violence in the past.

5. Conclusions

- This research concludes that intergroup cognitions moderate the link between collective memory of colonial violence and hostility toward former colonial powers. It thus contributes to the extension of the literature relating to the effects of collective memory of past conflictual events on contemporary relations between victim and oppressor groups. It makes it possible to understand, among other things, the hostility of which a colonizing power like France is the target in Africa; a continent on which it has colonized many countries and in which its current foreign policy, considered neocolonial, is rejected by citizens.

Declarations

- Author ContributionsAll authors made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the completion of this research.Conflict of InterestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.Ethical ApprovalAll participants provided written informed consent to participate in the research.Data Availability StatementThe raw data supporting the conclusions of this research will be made available by the authors, without any undue reservation.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML