-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2023; 13(2): 40-53

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20231302.02

Received: Nov. 22, 2023; Accepted: Dec. 13, 2023; Published: Dec. 23, 2023

Hurting or Therapy? Evaluating the Consequences of Talking about Workplace Injustice in Financial Institutions in Bamenda, Cameroon

Napoleon Arrey Mbayong, Fomba Emmanuel Bebeb

University of Bamenda, Cameroon

Correspondence to: Napoleon Arrey Mbayong, University of Bamenda, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The study aims at examining the consequences of talking about workplace injustice in Commercial banks in Bamenda, Cameroon. This study makes use of two types of talk: emotion and cognition talk. The study test three sets of paths: direct paths from both emotion and cognition focused talk to the victim-centred outcomes and a moderated path. The study adopted a cross-sectional survey. The sample for this study incorporated 166 workers of selected Financial Institutions in Bamenda. To test the hypotheses, we conducted moderated regression analyses. For each outcome variable, first, we controlled for gender and tenure. Secondly, we included the main effects of emotion and cognition talk respectively. Finally, we included the interaction terms. All variables were mean-centred to reduce multicollinearity. There are three main sets of findings a) significant interaction effects for three victim-centred outcomes of rumination, self-affirmation and active solutions (an asymmetry effect); b) significant main effects for emotion and cognition talk (symmetry effect); and, c) no significant interaction effects for two victim-centred outcomes of retaliation and psychological well-being.

Keywords: Talking, Workplace justice, Fairness, Commercial banks, Bamenda

Cite this paper: Napoleon Arrey Mbayong, Fomba Emmanuel Bebeb, Hurting or Therapy? Evaluating the Consequences of Talking about Workplace Injustice in Financial Institutions in Bamenda, Cameroon, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 13 No. 2, 2023, pp. 40-53. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20231302.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Organisational justice is a mature field of enquiry within the social sciences dedicated to the study of perceptions of fairness in the workplace. Hundreds of studies spanning over four decades converge on the notion that justice matters. It matters to such an extent that profound implications arise when individuals perceive unfairness at work. Workplace injustice has not only been perceived as a factor moderating performance in the workplace with implications on management of human resources. Unfair practices are equally psychological problems, which induce unpleasant emotions and cognitive experiences such as distress, anger, perceptual distortion, prejudices and frustration and draws in occupational health psychology closer to the management of human resources at work. Within regards to the mental health consequences of workplace injustice talk therapy has been a viable response capable of restoring the cognitive, emotional and behavioural deviations of workers to regain their health and perform maximally. As a subject of debate primarily within the fields of occupational health psychology, the idea of talk therapy has evolved over history from being a form of verbal therapy aimed at curing deep-seated psychological conditions (Freud & Breuer, 1895), to being viewed as effective if the release of one’s emotions is coupled with cognitive processing (Scheff, 2001; Greenberg, 2002). Today talk therapy is a dimension of occupational health interventions designed to assist workers disclose their feelings about injustice while talking about them through self-disclosure. In bringing this theoretical construct to life in the context of workplace injustice, through inductive research, this study makes use of two types of talk: emotion and cognition talk. Whilst emotion focused talk represents the release of strong negative emotions, cognition focused talk involves actively working towards resolving one’s problem (Ambrose, & Schminke, 2009).Given the negative consequences of such acts, as well as potential cost implications to an organisation and its employees, one can argue that it makes sense for justice scholars to include in their lines of enquiry a focus on how an injustice is experienced by those on the receiving end. Such an agenda might ask what it is that victims of unfairness do, feel and think following their brush with injustice, why, and whether they ever move on (i.e., recover) from such experiences? Ironically however, with an amassing body of literature dedicated to understanding how many types of justice there are, how they are distinguished from one another and how justice judgements are formed, the organisational justice field has largely failed to account for those who experience and suffer workplace injustice. Scholars have been making calls for well over a decade now urging for a shift in focus towards the victims of workplace injustice. The result has been, unfortunately, a neglect of the victim who is at the heart of an unjust encounter, as well as his/her unjust experience.This study examines talk; that is, conversation with others through spoken words. We will explore if, when, and how, talk can assist victims with their recovery process following their experience of organisational injustice. There are a few terms that will be explained in order to clarify the focus of this study. First, injustice and unfairness are used interchangeably throughout this study, with both referring to an individual’s subjective perceptions in the workplace. Second, the Oxford Online Dictionary defines a victim as a “person who has come to feel helpless and passive in the face of misfortune or ill-treatment”, and further as one who may possess “a victim mentality”. The word victim pertains both to one who has been aggrieved as it does to one who ‘plays the victim’ in order to justify perceived abuse. Third, recovery is understood as “a return to a normal state of health, mind or strength” (Oxford Online Dictionary). Finally, one can ask: why talk as a choice of a recovery intervention? Barclay and Saldanha (in press) outline a framework to facilitate our understanding of the role of recovery in the justice sphere. This study focusses on the experience of injustice from the victim’s perspective. It seeks to examine the aftermath of workplace unfairness, and to explore whether talk can function as a recovery mechanism for victims, and if so, how such a recovery process unfolds. The study also integrates the phenomenon of talk into a workplace (in)justice paradigm by exploring the consequences of engaging in talk. Given the aims of this study which is to investigate the place of talk to a victim in an injustice situation, we have posited that talk will lead to effective – i.e., positive outcomes for a victim – when emotion talk is coupled with cognition talk; in other words, when victims of workplace injustice are able to release their frustrations as well as organise their thoughts and re-evaluate their experience. the question that guides the study is: does talk operate as a recovery (therapy) mechanism, assisting victims with overcoming the negative effects of workplace injustice?

2. Literature Review

- One of the key debates which characterised the realm of occupational psychology research during the early part of the twentieth century disputed the viability of Freud’s hydraulic model of anger (Freud & Breuer, 1895). This model purports that the experience of negative events leads to the build-up of anger within an individual; if this pressure is not released via catharsis (verbal emotional discharge), it will cause an ‘explosion’ in the form of adverse physiological and psychological symptoms. A moratorium on this perspective (Bandura, 1973) instigated the rise of research which posited that what was missing from Freud’s early analysis (a point Freud made himself, albeit rather subtly) was a cognitive component. In other words, the talking therapy is effective when emotional discharge is coupled with mental processing.In understanding why, the combination of emotional discharge and cognitive processing go hand in hand, occupational and social psychologists concur on two insights, which underscore figure 1. First, in both literatures, it is argued that there is a preponderance of emotional expression in the immediate aftermath of a negative episode. Murray et al. (1989) demonstrated in an experiment on the effects of talk, that the expression of emotions dominated initial talking session. Rimé (2009) concludes that it is emotions that individuals initially share following their experience of a negative or challenging encounter. Emotional discharge is paramount since it triggers a host of socio-affective benefits such as empathy, validation and shared understanding (Rimé, 2009). Additionally, inhibition (that is not talking by consciously withholding thoughts and feelings about an event) can lead to a host of physical and psychological dysfunctions (Pennebaker, 1990). However, although emotional discharge is beneficial, it brings about temporary relief only. This leads to the second insight. Articulation which gives rise to the act of processing one’s experience, such that thoughts are restructured, organised, labelled and assimilated, provide one with a sense of coherence to their experience, making it more likely that they can process an event and ‘move on’ from it (Rimé, 2007; Pennebaker, 1997). Indeed, a ‘positive’ change in individuals, in the form of reduced anger, reductions in symptomatology and interpersonal distress, a sense of resolution, and improved physical and mental health is not evident until emotional discharge is coupled with cognitive processing (Geen & Murray, 1975; Greenberg, 2002; Greenberg et al., 2008). Otherwise, emotions may dissipate, but they do not disappear – they continue to simmer below the surface, and talking about them can contribute to individuals expending physical and mental energies on continual rumination. Comparable results are demonstrated within social psychology, with the combination of sharing one’s emotions, and cognitively reframing and modifying one’s schema, leading to optimal results such as lowered emotional distress, increased positive mood and self-esteem changes (Murray et al., 1989; Nils & Rimé, 2008; Rimé, 2009).This is the theoretical reasoning that underlies the rationale of the model to be tested in this study (figure 1). Individual paths from both types of talk to the outcomes will be tested, as well as an interaction effect, wherein cognition talk operates as a moderator between emotion talk (the preponderance of which following a negative episode is outlined above) and the victim-centred outcomes. It is argued that emotion talk alone will not bring about the desired predicted directions of the victim-centred outcomes; this will occur when emotion talk is coupled with cognition talk. Emotion talk, is a type of talk that embodies the release of strong negative emotions. It is the affect underlying this talk that can trigger victims to engage in retaliation. This notion holds intuitive appeal: pent-up frustration and anger characterising emotion talk can give way to engagement in a response that is a natural outlet for such feelings.The interaction between emotion talk and cognition talk and outcomes

| Figure 1. Schematic hypothesis model of the consequences of talk in the context of workplace injustice (Source: Researchers, 2023) |

3. Methods and Procedure

- Participants & ProcedureThe study adopted a cross-sectional survey. A convenient sampling technique was used. Key questions this study asked was; Does talk operate as a victim-centred recovery mechanism as evidenced in clinical and social psychological literatures, assisting victims with overcoming the negative effects of workplace injustice? In other words, what are the consequences of talk? A survey was deemed the most appropriate methodology to explore such research aims. Unlike interviews, surveys allowed for ease of data collection with regards to time resources. They also allowed for an assessment of the psychometric properties of the newly developed measure of talk.The sample for this study comprised 166 permanent workers of Financial Institutions in Bamenda (17 category 1, 2 micro finance institutions and commercial banks) who have worked with the financial institution for at least three years and above. All in all, surveys were made available to 200 workers and of these, 166 chose to participate, (82% response rate) which we obtained via our own consultancy contacts. The average age of participants was 43 years (SD = 15.66), and their tenure with the company was on average 7.94 years (SD = 7.33). Financial institutions were chosen as an appropriate sample for two reasons. First, although the research questions comprising did not necessitate a specific type of organisation, we were keen to recruit participants who potentially would experience issues of unfairness on a regular basis since this would allow an investigation of the merits of talk as a recovery intervention in a rich context. We first visited the Managing Director of most of the financial institutions a number of times attain a detailed understanding of the nuances of their organisation. The purpose and aims of the research were outlined as was the content of each survey, how much time we would spend at each branch and what assistance we required from each branch management. We agreed upon a paper-and-pencil approach to conduct the research where each respondent would receive a paper-based survey. We spent approximately ten months with these organisations. In addition to employee data, we also gathered survey data from supervisors. Supervisor data was gathered in order to counteract biases inherent in relying on single-source data from employees. The supervisors were identified by each depot’s general manager. Thirteen supervisors took part and provided complete data on all 166 employees. Supervisors were asked to respond on the following scales for each employee: job performance and organisational citizenship behaviour. They also provided neuroticism ratings. However, this data did not bear any results of significance. Though the Cronbach reliabilities for each of these scales was acceptable (>.70), this data did not produce any significant results.MeasuresEmployees provided ratings of emotion talk, cognition talk, retaliation, rumination, self-affirmation, active solutions and psychological well-being. The following control variables were gathered: gender and tenure. In order to counteract issues of common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003), the order of questions in the survey were counterbalanced (to avoid unduly influencing a respondent’s interpretation) and respondents were informed that there were no right or wrong answers.Emotion Talk. Emotion talk was evaluated using a measure created for this study based on previous research. The four validated items included, ‘I let all my negative feelings out’ and ‘I let off steam “I talked to a friend in another division’ ‘I feel like nobody was listening’. Respondents were asked to what extent they engaged in talk following their experience of workplace injustice. Items were measured on a 7-point scale from 1 = never to 7 = always. (α = .83).Cognition Talk. Cognition talk was evaluated using a measure created for this study. The four validated items included, ‘I talked about a possible solution to what I experienced’, ‘I talked about actions I can take’, “I relayed the events as they happened”. Respondents were asked to what extent they engaged in talk following their experience of workplace injustice. Items were measured on a 7-point scale from 1 = never to 7 = always. (α = .86).Retaliation. Retaliation was measured using four items from McCullough, Rachal, Sandage, Worthington, Brown and Hight’s (1998) Transgression-Related Interpersonal Motivations Inventory. Sample items included, ‘I’ll make him/her pay’, ‘I wish that something bad would happen to him/her’ and ‘I’m going to get even’. Items were measured on a 5-point scale from 1 = never to 5 = always. (α = .91).Rumination. Rumination was measured using four items from the Cognitive Emotional Regulation Questionnaire developed by Garnefski et al. (2001). Sample items include, ‘I often think about how I feel about what I have experienced’, ‘I am preoccupied with what I think and feel about what I have experienced’ and ‘I dwell upon the feelings the situation has evoked in me’. Items were measured on a 5-point scale from 1 = never to 5 = always. (α = .85).Self-affirmation. Self-affirmation was measured using three items from a six-item self-affirmation scale developed by Pietersma and Dijkstra (2012). Sample items include: ‘I remind myself that I do some things very well’ and ‘I think about all the things I can be proud of’. One-item was used from Hepper, Gramzow and Sedikides’ (2010) six-item self-affirming reflections scale, ‘I remind myself of my values and what matters to me.’ Items were measured on a 5-point scale from 1 = never to 5 = always. (α = .92).Active solutions. Active solutions were measured using four-items from Carver’s brief COPE inventory (Carver, 1997). Sample items include: ‘I concentrate my efforts on doing something about it’, ‘I take additional action to try and get rid of the problem’ and ‘I do what has to be done, one step at a time.’ Items were measured on a 5-point scale from 1 = never to 5 = always. (α = .81).Psychological well-being. Psychological well-being was measured using five items from the Satisfaction with Life scale (Diener, 1984). Sample items include: ‘In most ways my life is close to my ideal’, ‘The conditions of my life are excellent’ and ‘I am satisfied with my life’. Items were measured on a 5-point scale from 1 = never to 5 = always. (α = .87).Gender. Gender was controlled for two reasons. First, there is evidence that men hold more favourable attitudes towards retribution and revenge, and this may impact upon both retaliatory outcomes, as well as clouding their levels of emotion talk (Stuckless & Goranson, 1992). Second, in line with popular stereotypes, women are often found to be more prone to talk via sharing their emotions compared to men (Bergmann, 1993) though this has not always been evidenced in research (Rimé, 2009). (gender: 1 = male, 2 = female).Tenure. Employee tenure was controlled for given that experience within a company may influence the degree to which an employee is able to manage their experience of injustice. For instance, it may affect the degree to which employees engage in one or both types of talk, or the way in which they engage (or not) in retaliation, rumination or the search for active solutions in particular. Research on responses to stress at work cite tenure as moderating an individual’s ensuing responses, such that knowledge of an organisation’s systems and procedures can lead to more adaptive responses (i.e., Parasuraman & Cleek, 1984). Respondents were asked to report the total length of time they had worked for their company; this information was verified with company records (tenure: in years).Data AnalysisTo test the hypotheses, all analyses were run through SPSS version 21 and we conducted moderated regression analyses. For each outcome variable, in step 1, we controlled for gender and tenure. In step 2, we included the main effects of emotion and cognition talk respectively. In step 3, we included the interaction terms. All variables were mean-centred to reduce multicollinearity (Aiken & West, 1991). To assist in interpretation of the interactions, simple slopes were produced diagrammatically (Dawson, 2014) and plotted according to procedures outlined by Aiken & West (1991), by examining the statistical significance of the slopes at low, medium and high levels of the moderator variable.

4. Results

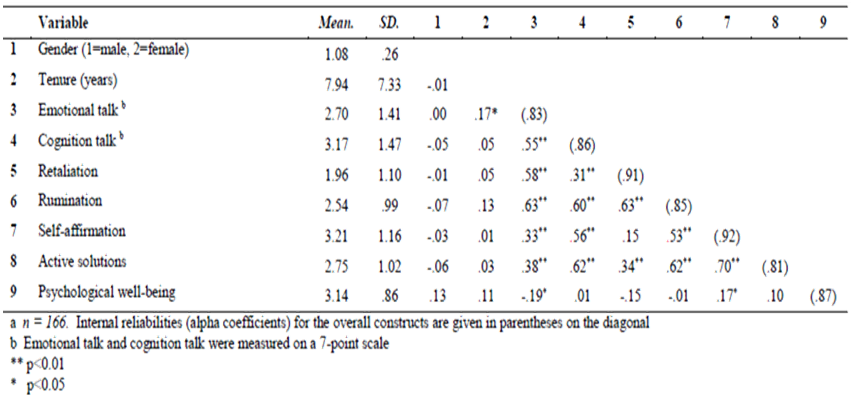

- Preliminary analysis: Confirmatory factor analysisGiven that each of the variables within this study were essentially rooted in an affective, cognitive or behavioural component, and in order to verify their separation as constructs, we ran a confirmatory factor analysis for each variable deployed: emotion talk, cognition talk, retaliation, rumination, self-affirmation, active solutions and psychological well-being. As predicted, in line with the study’s hypotheses, each variable loaded onto its separate factor (such that a seven-item factor solution emerged, loading onto separate factors) and provided a good fit to the data (Kline, 2005): (Χ2 [df = 327] = 694.776, CFI = .90, RMSEA = .08, SRMR = .07).Descriptive Statistics, correlation and Reliabilities Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics, correlations and scale reliabilities for the variables in the study. Coefficient alphas are shown in parentheses on the diagonal.

| Table 1. Descriptive statistics, correlations and reliabilitiesa |

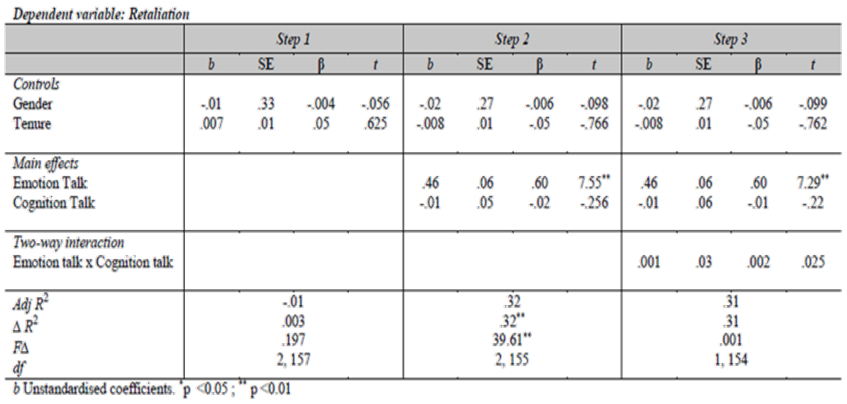

| Table 2. Moderation analyses: Retaliation (hypotheses 1a, b, c) |

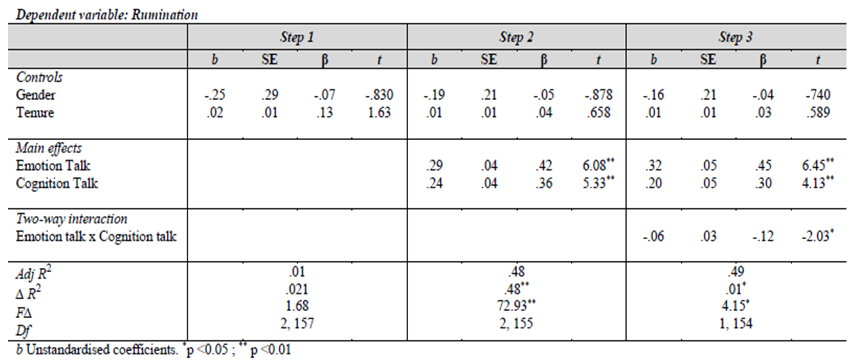

| Table 3. Moderation analyses: Rumination (hypotheses 2a, b, c) |

| Table 4. Moderation analyses: Self-affirmation (hypotheses 3a, b, c) |

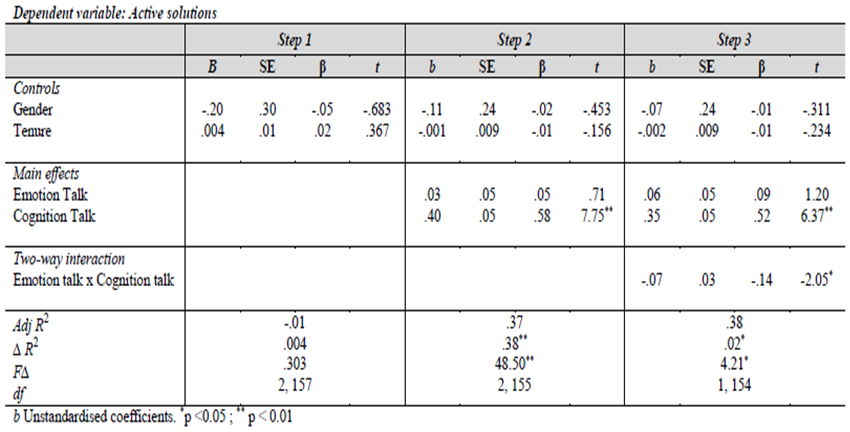

| Table 5. Moderation analyses: Active solutions (hypothesis 4a, b, c) |

| Table 6. Moderation analyses: Psychological well-being (hypothesis 5a, b, c) |

5. Discussion

- “The memory of an injury to feelings is corrected by an objective evaluation of the facts, consideration of one’s actual worth, and the like.” Freud (1893/1962: 31)This study began by arguing that a ‘talking cure’ or therapy is effective when emotional discharge is coupled with cognitive processing. In translating this to the present study, and drawing on literatures in the domain, we have posited that talk will lead to effective – i.e., positive outcomes for a victim – when emotion talk is coupled with cognition talk; in other words, when victims of workplace injustice are able to release their frustrations as well as organise their thoughts and re-evaluate their experience. There are three main sets of findings arising from the present study and each will be discussed in turn: a) significant interaction effects for three victim-centred outcomes of rumination, self-affirmation and active solutions which point to an effect we are referring to as an asymmetry effect, b) significant main effects for emotion and cognition talk which we are referring to as a symmetry effect, and, c) no significant interaction effects for two victim-centred outcomes of retaliation and psychological well-being.A) Evidence of “asymmetry effects”: Significant interaction effects for three victim-centred outcomes of rumination, self-affirmation and active solutionsSignificant interaction effects were found for three victim-centred outcomes: rumination, self-affirmation and active solutions. A consistent pattern of findings was uncovered in relation to each of these outcomes, and these will be commented upon in turn.Findings in relation to rumination, self-affirmation and active solutions, what this study provides evidence of is what we will refer to as an asymmetry effect between high and low level of both types of talk, emotion and cognition. In other words, cognition talk appears to be most effective at low levels of emotion talk, and less effective at higher levels of emotion talk. Theoretically this finding points to the idea that victims of workplace injustice will reap greater benefits relating to positive recovery outcomes, when their levels of venting decrease and thoughts about how to move past an injustice increase. Otherwise, high levels of venting drown out any potential beneficial effects of cognition talk. One can argue that this finding is instinctive, and indeed it is. Theoretically, it has been alluded to wherein scholars posit that prolonged emotion discharge exacerbates tension (Kennedy-Moore & Watson, 1999). And, to my knowledge, only one experimental study has alluded to such an effect. Murray et al. (1989) found that recovery (in the form of self-esteem changes) was most prominent in those subjects whose pattern of talk over a four-day period showed signs of decreased emotion expression and increased cognitive changes. The present study makes an added contribution to this research, producing complimentary and novel insights from the realm of workplace injustice. It concurs with occupational and social psychological research that both emotional discharge and cognitive processing are pertinent to recovery; while the former allows for a release of negative emotions which would otherwise cause distress through inhibition, the latter allows for the re-evaluation which provides a necessary focus to move on. The added contribution of the present study is in its elucidation of how the differing levels of emotion and cognition talk function in a real workplace setting.B) Evidence of “symmetry effects”: Significant main effects for emotion and cognition talkFindings from this study also indicated that both emotion and cognition talk impact certain victim-centred outcomes of relevance in a symmetrical fashion. These findings are of relevance since they support as well as challenge the theoretical contentions of this study. First, with regards to ‘supporting’ theoretical contentions is the finding of the positive association between emotion talk and retaliation; it was predicted that the association between emotional talk and retaliation would be attenuated in the presence of cognition talk. Though there was no support for this interaction effect, if future research similarly does not find an interaction effect, we may speculate whether emotion talk alone has the effect of increasing retaliatory intentions, with no attenuating impact evident from cognition talk. Does this mean that feelings of retaliation are so strong that cognition talk can play no part in this outcome at all? Or, do these findings perhaps point to a missing link of time such that early on ‘in the heat of the moment’ the presence of emotion talk is so grave that cognition talk has no role to play, until perhaps these feelings have dissipated? This notion was alluded to above in the findings for an asymmetry between the roles played by both types of talk. This finding warrants much closer attention in future research because it has a bearing on whether talk can actually mitigate a victim’s engagement in this outcome which can be both emotionally and cognitively taxing for a victim and lead to potentially negative implications for him/her in the eyes of the organisation.Second, with regards to ‘challenging’ theoretical contentions are the findings of the association between cognition talk and self-affirmation and active solutions. Though it was predicted that the presence of both types of talk would confer benefits, it appears that with cognitively focused outcomes, cognition talk alone may lead to positive benefits for a victim; this is in spite of a significant interaction effect between emotion and cognition talk found for these two outcomes. The notion that cognition talk can lead directly to positive benefits for a victim, without the presence of emotion talk, has been noted in one previous study. Nils & Rimé (2008) found that compared to talking about how one feels about a stressful event, cognitively reframing the event produces recovery (in the form of attenuating distress and rumination). This notion merits future research as if this finding holds, it has significant implications on the role played by emotion talk and the collective impact of emotion and cognition talk.C) No significant interaction effects for two victim-centred outcomes of retaliation and psychological well-being.With regards to PWB, this study had hoped to demonstrate the impact of talk on victim-centred recovery that spilled over into one’s life, beyond the realm of work. There are three possible reasons for the non-significant interaction findings. First, one could question whether talk has a bearing on recovery at all outside a victim’s place of work? Though there may be a case for this, it may be premature to accept this explanation particularly in light of previous studies on disclosure which have demonstrated a positive impact of expression on PWB (i.e., Barclay & Skarlicki, 2009). Second, perhaps the injustice experienced by victims was not ‘severe’ enough to merit an effect on their life in general.And finally, we can turn once again to the importance of time. Studies that have shown the impact of expression on PWB have done so over the course of a few days, or after a one month follow up (Pennebaker & O’Heeron, 1984; Segal et al., (in press); Barclay & Skarlicki, 2009). There is merit in the idea that assessments of this outcome are best captured over a period of time; though a victim may disagree with the survey item for PWB ‘the conditions of my life are excellent’ at the moment an injustice occurs, perhaps as talk progresses – allowing victims to emotionally discharge and cognitively process the event – they feel greater positivity about their lives.

6. Limitations

- A limitation central to this particular study is that it did not account for the role of time. Talk has been construed as a static construct given that victims of injustice were asked to think back to an injustice they experienced and how they reacted in response to it. It is perhaps naïve to assume that working through an injustice is so straightforward and static. What is missing from this study is an analysis of time and how both talk and its impact on outcomes unfolds as a function of time. An episode of recovering from injustice may not be so linear, but rather an ongoing process of experiencing feelings and cognitions as an event is worked through. Such questions that beg investigation include: are both types of talk engaged in, in one day? Do victims fluctuate in the types of talk they engage in? If so, how does this bear upon immediate as well as more temporal outcomes? Again, these are complex questions which drive at the heart of how an episode of talk unfolds. It is suggested that the best methodological approach to assess such questions is experienced sampling, and this is outlined below. Not only will it avoid some of the problems inherent in the present study’s design, such as measurement context effects but it will allow the capturing of the phenomena of interest as and when it occurs, thus permitting analysis of how an episode of talk unfolds on a daily basis. Such studies could use mix methods so that we can triangulate methods and results. This is purely quantitative and qualitative efforts could have been value additive.

7. Suggestions for Future Research

- The idea of an ‘asymmetry’ between both emotion and cognition talk, in their combined impact upon recovery, is worthy of future investigation. This is a novel contribution to the study of talk as a recovery intervention. Though occupational and social psychological literatures allude to the beneficial impact of a combination of emotional discharge and cognitive processing – construed as both emotion and cognition talk in the present study – what the present study demonstrates that this combination is not so straightforward. Specifically, cognition talk – whether it is engaged in a little or a lot – can be drowned out by high levels of venting. Put another way, at higher levels of emotional intensity, the effects of cognition talk are cancelled out. This insight merits further investigation. As a starting point, researchers must seek to replicate findings of this study.

8. Conclusions

- As early as the nineteenth century Freud recognised the value of talk which coupled emotional discharge with an objective evaluation of one’s negative experience. A steady trajectory of occupational and social psychological research attests to such a ‘talking cure’, and it is this enquiry that has formed the basis of this study investigation, conducted in the context of workplace injustice. Overall, an array of insights emanates from this study shedding light on the interplay between emotion and cognition talk, as well as its interaction on victim-relevant outcomes.This study has demonstrated that, indeed, a combination of emotion and cognition talk impacts a victim from the negative effects of a workplace injustice. One of the novel findings of this study points to an asymmetry effect such that higher levels of emotional intensity (evident in higher levels of emotion talk) actually function to cancel out the positive effects of cognition talk. A further finding hints at a symmetry effect between the type of talk and a given outcome: whether there exists congruence between emotion and cognition talk and outcomes rooted in either affect or cognitive processing respectively, merits further investigation. The present study makes an added contribution to this research, producing complimentary and novel insights from the realm of workplace injustice. It concurs with occupational health psychological research that both emotional discharge and cognitive processing are pertinent to recovery; while the former allows for a release of negative emotions which would otherwise cause distress through inhibition, the latter allows for the re-evaluation which provides a necessary focus to move on. The added contribution of the present study is in its elucidation of how the differing levels of emotion and cognition talk function in a real workplace setting. This notion merits further investigation.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML