-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2023; 13(2): 29-39

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20231302.01

Received: Aug. 24, 2023; Accepted: Sep. 8, 2023; Published: Sep. 12, 2023

Safety Education as a Psychosocial Risk Management Plan: Effect on Perceived Safety Climate of Workers in Construction Enterprises in Mezam, Cameroon

Kebuya Nathaniel Nganchi, Fomba Emmanuel Mbebeb, Sigala Maxwell Fokum

Department of Counseling Psychology, The University of Bamenda, Cameroon

Correspondence to: Fomba Emmanuel Mbebeb, Department of Counseling Psychology, The University of Bamenda, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Many enterprises operating in high risk work settings practice physical risk mitigation strategies with low regard for psychosocial risk management plan that appears a more sensitive response to psychosocial risk factors. This expresses a critical human resource management function, and questions the responsive safety management systems put in place to ensure safety climate and ensuing safety performance of employees in construction enterprises. The question is whether psychosocial risk management constitutes a viable component of safety measure following operations at high risk with prevailing psychosocial hazards. Within the theoretical frame of Person-Environment Fit theory, the study investigated the influence of safety education, a dimension of psychosocial risk management on perceived safety climate of employees in the construction sector. A total of 318 participants were recruited from BUNS and EDGE Construction sites in Mezam, Cameroon. An instrument with determined reliability coefficient was used to collect information. Data were entered into SPSS and analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Analysis reported that the core and oval components of safety education were able to predict variations in perceived safety climate of the employees. It was evident that safety education is the first line of action in psychosocial risk management plan, and should be reinforced to preserve a sustainable safety climate for effective operations of workers at construction sites. Recommendations were made on how to integrate traditional safety education strategies into mainstream psychosocial risk management plan to promote perceived safety climate.

Keywords: Psychosocial risks management, Safety education, Safety climate, Construction sector

Cite this paper: Kebuya Nathaniel Nganchi, Fomba Emmanuel Mbebeb, Sigala Maxwell Fokum, Safety Education as a Psychosocial Risk Management Plan: Effect on Perceived Safety Climate of Workers in Construction Enterprises in Mezam, Cameroon, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 13 No. 2, 2023, pp. 29-39. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20231302.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) management systems have of late received immense attention due to their roles in fostering cognitive, emotional and behavioral stability of workers, which are consequent drivers of safety behaviors and organizational performance. Despite the competitive edges of industrialization and interest in physical hazards, psychosocial risk factors have been recognized as a disturbing occupational health and safety challenge due to increasing variety of occupational accidents that inflict damages on human resources (Fomba, Nota, Neku, 2021; Omid, Eskandari & Omidi, 2021). This attracts key concerns in OHS circles, drawing in Perceived Safety Climate (PSC) as a measure of performance. PSC is a dimension of organizational culture with specific interest in policies, practices, and procedures, which purport to respond to psychosocial risk factors to ensure safety attitude and practices of workers. Presently, awareness of the importance for safety performance of organizational, managerial and social factors, have increased (Kines, Lappalaine, Mikkelsen, Olsen, Pousette, Tharaldsen, Tómasson & Törner, 2011). This is often attributed to continuous awareness creation and management of risk factors that affect the physical and psychological states of workers in the process of performance. Particular focus is on high risk work settings such as construction sites, which is reputed for inducing significant psychological distress with general signs of stress, fatigue, anxiety, anger and moodiness (Derdowski & Mathisen, 2023; Frimpong, Sunindijo, Wang, Boadu, 2022). These are health menaces faced inter-alia by workers due to psychosocial hazards in the workplace and consider psychosocial responses as very appropriate. Psychosocial risk factors are potential dangers noted for inducing psychosomatic disorders with the capacity of moderating performance and productivity in enterprises. Among others, lack of social support within the organization has been perceived as capable of explaining stress resulting from perceived risks factors (Talavera-Velasco, Luceño-Moreno, Martín-García & Garcia-Albuerne, 2018) and this has implications in safety climate of any organization. In this respect, Psychosocial Risk Management (PRM) becomes an invaluable facility in responding to psychosocial risk factors and ensuring safety climate in work places. Several motives no doubt exist why experts agree that psychosocial hazards in the workplace is perceived to have significant potential dangers for workers (Leka & Jain, 2010). In response, psychosocial risk management contributes to mitigate risks, foster safety climate of organizations and safe keep human resources in construction sites. Furthermore, recognizing that environmental conditions, safety-related policies, programs, and general organizational climate are predictors of perceived safety climate (Dejoy et al. 2004), the current study is interested in safety education, a dimension of psychosocial risk management plan as a determinant of perceived safety climate. The study will be analyzed within the theoretical frame of Person-Environment Fit, which suggests congruity between workers’ attributes and organizational attributes as a measure of performance. In the theory, Van Vianen (2018, 77) “assumes that people have an innate need to fit their environments and to seek out environments that match their own characteristics.” More to that the notion of person–environment (PE) is drawn from interactional psychology suggesting the interplay between the organism and the environment as a primary booster of human action (Cooman & Vleugels, 2002). This is essential in understanding safety education of construction workers, and perceived safety climate as capable of promoting safety behaviors and performance.Psychosocial risk management has obligations to assess and manage all types of risk on workers’ health and safety (Dijk, 2010), and strategies such as health and safety education, training, risk identification and psychosocial rehabilitation have been used as management strategies. From a practical perspective, understanding the role of safety education on perceptions of workplace safety would benefit management’s decisions regarding workers’ adaptability, general work effectiveness, accident frequency, implementation of safety policies and handling of education-related accident characteristics (Gyekye & Salminen, 2009). There is no gainsaying that psychosocial risks factors have often been accused of work-related accidents and absenteeism (Cheyne, Tomás & Cox, 2002), including general safety climate which in turn affects cognitive, affective and behavioral dispositions of employees during operations. To Omid et al. (2021), safety climate shows the attitude and general perception of the organization’s management regarding safety. Recognizing that some types of psychosocial hazards may cause serious disruption to work behavior and health of workers, the situation is even alarming in construction sites where physical, chemical, biological and ergonomic risk factors are capable of moderating safety performance. This is the rationale of the current discourse on psychosocial risk management, the application of risk management framework to mitigate psychosocial risks in the workplace (Schene, 2000), and constitute a key dimension of a comprehensive risk management system of a company.In terms of risk management strategies, safety education, a strategy deployed by organizations to provide employees with a certain degree of lessons, autonomy and control in their day-to-day activities (Baron, 1986), should be the first line of action in psychosocial risk management. O’connor, Flynn, Weinstock & Zanon (2014) further positioned education and training as the process of transmitting knowledge, and efforts designed to engage trainees with the goal of influencing motivation, attitudes, and behavior for the purpose of improving workers’ health and safety on the job. Interest on training draws from the fact that learning is an adaptive mechanism at the workplace and knowledge, skills and attitude acquired will respond to reduce hazards and promote safety climate. In this respect, perceived safety of workers can thus be determined if the workers are versed with the necessary knowledge and skills to manage psychosocial risk factors which workers are exposed to in the process of carrying out their assignments. Following the awareness that workplace hazardous patterns expose workers to psychological distress and physical health problems such as diseases and accidents (Fomba, 2020), mitigation strategies become very critical. Therefore, the promotion of occupational safety and health is not only an overall improvement in working conditions but also an important business strategy to drive along motivation of workers, safety behaviors and climate of the organization. Consequently, incorporating workplace safety education activities into training programs and post training activities can be very vital for promoting a working climate that is safe (Hearst, 2023). Although accident and safety research has traditionally been done on work, traffic, home and leisure (Gyekye & Salminen, 2009), the present study extends to construction sites with inherent psychosocial hazards. The question at stake is whether psychosocial risk management strategies can be responsive to hazards and influence perceived safety climate of employees. This no doubt justifies the current interest on the role of safety education and training on perceived organizational climate in the construction sector in Mezam, Cameroon.

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Psychosocial Risk Management

- The notion of psychosocial risks management and risks related issues in organization could be traced from the end of the 18th century due to adverse working conditions (Le Roux, 2011). Since then efforts had been made to build a body of knowledge around safety education as a key component of safety management. Psychosocial risk management is the application of risk management framework to psychosocial risks in the workplace (Zohar, 1980). These are techniques that different workplaces put in place to see that risks are mitigated as much as possible in work places. To Bagnara (2001), psychosocial risks is an approach that looks at individuals in the context of combined influence that psychological factors and the surrounding social environment have on the physical and mental wellness of their workers and their ability to function. This approach is used in a broad range of helping professions and useful in reinforcing safety behaviors in construction companies, and emphasis is on behavioral safety approaches. This draws from the fact that man is a resource that positions itself at the centre of safety in different operations and is always at risk of hazards. In generic terms, these are organizational and psychosocial dimensions capable of inducing maladaptation, tension and stress responses that are adverse to safety climate (Talavera-Velasco et al., 2018). Construction workers are often at high risk of physical and psychological illness due to exposure to hazards such as pressure to carry out their tasks and this requires the necessary support from colleagues and administration. Although hazardous expressions are usually determined by individual, environmental and situational factors (Fomba, 2020), individual dispositions are often held responsible for safety education and compliance to risk safety regulations in construction companies. This is only possible if workers are aware of safety matters and oriented towards the use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) where and when necessary. Furthermore, Fomba et al. (2021) noted that psychosocial risks factors in the likes of mental workload and work intensity are able to determine variation in psychological health of workers exposed to workplace hazards. This is a call for concern with implications on safety management strategies, which will build on psychosocial risk management strategies such as safety education. Psychosocial risk management strategies are inherent in organizational safety management systems to respond to the disturbing situations of safety hazards. Such applications are not only designed to ensure the well-being of workers but also to contribute positively to safety climate of organizations. This is in line with occupational health and safety legislations, which are designed to mitigate workplace hazards. Interestingly, the premier line of management action is safety education, which is a strategy to help workers develop a better understanding of safety, management strategies and promotion of a conducive safety climate for operation.

2.2. Safety Education

- Amongst psychosocial risk management plan put in place to respond to psychosocial hazards in the workplace, safety education remains a core dimension. Stolean (2001) defined safety education as the acquisition of knowledge and skills necessary in dealing with emergencies, resulting from accidents, and also preventing accidents through early removal of hazards. Baron (1986) further asserts that it is the way organizations provide their employees with a certain degree of lessons, autonomy and control in their day-to-day activities. In terms of functions of safety education, Hearst (2023), opined that safety education helps prevent accidents, promotes safety among workers, helps ensure well-being, saves companies’ money in the long run and can establish, maintain a company's safety reputation. Safety education is an important tool for informing workers and managers about workplace hazards, identification and controls in order to foster safety performance and it is an indispensable and adaptive strategy designed to maintain physical, mental and social health within the workplace. In context, it is a series of ideas, statements, practices, instructions and warnings that provides awareness about possible harms and injuries to minimize injuries and fatal consequences in the construction industry. In this respect, health and safety training programs need to adapt to the different work contexts of a given group of workers in order to ensure safety behaviors and safety climate of the organization. Griffiths (2010) observed that safety education can have favorable outcomes on employees such as job satisfaction and increased well-being, and the organization in terms of commitment, productivity, and decreased in turnover behavior. It is evident that safety education in the construction industry stand to have enormous benefits as in other sectors such as higher quality work, improved safety practices, and increased efficiency. Moreover, education can help professionals stay up-to-date with the latest safety technologies and techniques giving them a competitive advantage (Nitesh, 2023). The competitive edge of educational attainment in a safety climate analysis could provide a potent proactive safety management tool, as they could indicate a need for special safety programs for a particular group (O’connor, Flynn, Weinstock & Zanon, 2014). This is critical with the safety climate of any organization particularly with the recognition that a higher level of education will promote strategic thinking, develop workers’ perspectives to enable them systematically analyze, store, and rightly use information to enhance safety behavior (Gyekye & Salminen, 2009). This is the rationale for investigating safety education as a dimension of psychosocial risk management strategy capable of influencing perceived safety climate among construction workers exposed to hazards during their operations. There has been a wave of interest in safety education, safety behavior and safety climate with evidences of studies in the domain. Tobi et al. (2001) found that empowerment-based hazardous materials training affected safety conditions, improved work environment, individual awareness, increased attempts and successes in advocating for workplace health and safety changes, and work practices. In another study, Gyekye & Salminen (2009) examined the relationship between educational attainment with focus on safety perception and compliance with safety management policies and accident frequency and results suggested a positive association between education and safety perception considering that higher-educated workers recorded favorable perceptions of safety, complied to safety procedures and recorded the lowest accident involvement rate. In another study Agumba et al. (2018) determined health and safety elements of the organization following employee involvement and empowerment, and results showed that employee empowerment did not influence health and safety performance with low level of practice in the companies. Although the results were not significant, many parameters could have been responsible that were expected to be controlled during the investigations since majority of studies reviewed herein recoded significant results.

2.3. Perceived Safety Climate

- Safety climate is a key aspect of organizational context and capable of determining workers’ safety outcomes and often considered as a dimension of organizational culture. Generally confusion often abound with the distinction between climate and culture in some domains. While safety culture refers to the underlying assumptions and values that guide behavior in organizations rather than the direct perceptions of individuals (Day et al., 2014), safety climate is the shared perceptions with regard to safety policies, procedures and practices in an organization (Zohar 2011). The later serves as a collective frame of reference for employees that provide cues about expected behavior and outcome contingencies related to safety (Zohar 2010). A molar view of safety climate is interested in perceptual, collective and multidimensional values of an organization that induce an experiential and normative influence on individual and group behaviors through safety seeking behaviors. Therefore, describing safety climate as a unified set of cognitions held by workers regarding the safety dimensions of their organization (Zohar, 1980) positions safety climate as a specific form of organizational climate based on individuals’ evaluation of their experiences of safety. This narrows down to the concept of perceived safety which is the processing of information on safety and interpretation, and this is a highly subjective experience by individual workers. It has been recognized that shared perceptions about the value and meaning of safety have been shown to influence safety values across a range of industries, which deal with individual and environmental hazards. Recognizing that occupational accidents give rise to much human suffering as well as high costs for society, companies and individuals (Kines et al., 2011), it is imperative to reinforce safety climate to promote feelings of security, which is incidental to individual and organization performance. From a hedonistic standpoint, a public space in a workplace that is perceived as safe could potentially be experienced as comfortable, and this is typical with outdoor work activities. Workers naturally perceive the space as non-threatening and it positively influences the level of comfort the person experiences (Mehta, 2014), with competitive edges to the employee and the organization. According to Nahrgang et al. (2011), safety climate stand to influence the motivation to work safety, the type of safe behaviors, and safety outcomes such as accident and injury prevention. It is also evident that safety climate influences individual processes in terms of cognitive sense making, motivation, and behavior (Zohar, 2011). Safety climate perceptions are characterized as being intrinsically descriptive and cognitive in their nature with reference to observable features of organizational safety experienced by employees in their daily interactions (Guldenmund 2000, Zohar & Luria 2005). Furthermore, safety climate is one of the factors involved in preventing and reducing occupational accidents not excluding its positive impact on workers’ safety performance (Omid et al., 2021). On the question of safety climate and safety behavior, Guo et al. (2020) reported the effect of safety climate on safety attitude, safety communication, safety policy, safety education and training, management commitment, and safety participation. This implies that safety climate can produce much more benefits to employees’ stability at work, performance and productivity while promoting both material and psychological benefits from the work environment.

2.4. Background and Orientation of the Study

- There is no doubt that psychosocial risk factors, safety climate and behavior have attracted the interests of many professionals and researchers in the construction sector. Although the current focus is on psychosocial risk hazards, it does not undermine chemical, biological, physical and ergonomic risk factors that affect workers in the construction sites of Edge and BUNNs companies, and therefore attracts mitigation responses to ensure a safe climate. Recognizing economic gains derived from work, safety management appears compromised by occupational hazards, which downplay behavioral states and actions of workers. In many construction industries injuries and casualties result from a lack of attention to safety measures in the industry (Omid et al., 2021) and absence of effective safety education had been perceived as regressive to safety climates. In high risk work settings the level of risk is critical where environmental stressors compound psychosocial risk management strategies, health and performance of workers (Fomba et al., 2021). This expresses a dire need for management commitment to safety, priority of safety, and pressure from safety regulations and procedures. This can be possible through safety education and training amongst others. The prevalence of hazardous substances that moderate performance with accompanying education and safety measures have been observed and the question is whether safety education initiatives can predict safety climate of the worksites as perceived by employees of the company. Despite the fact that safety climate has been shown to improve safety outcomes in production companies (Derdowski & Mathisen, 2023; Gyekye & Salminen, 2009), the safety climate of the companies still remain skeptical. The question is whether in Edge and BUNS Construction companies, perceived safety climate could be affected by enhancing knowledge of workers on safety policies, practices, procedures in local enterprises. Past studies hold that training classes for workers, encouraging group discussion, explaining the importance of safety in the workplace, and technical measures can positively affect workers’ safety behavior, increase performance and promote safety climate (Omid et al., 2021). Although this study was realized out of the local context, the assumption still holds that educational attainment in a safety climate could provide potent proactive safety management information (Gyekye & Salminen, 2009) capable of responding to the demands of perceived safety climate. This is often a quagmire to local enterprises especially the construction companies, where safety policies are often difficult to come by, lest of implementation as a measure of education. Whereas it has been acknowledged that psychosocial risk factors contribute to hazards and accidents in high-risk construction sites, research in the domain remains dispersed particularly in the area of psychosocial hazards, management and perceived safety climate. There is no doubt that some studies have been realized on psychosocial risk factors, consequences on workers and management strategies, but the literature remains fragmented (Frimpong et al., 2022) and expresses a dire need for more studies in the domain particularly in high risk work settings like the construction sector.

2.5. Theory and Model of the Study

- The Person-Environment (P-E) Fit theory (Van Vianen, 2018) has been used to explain the relationships between safety education and perceived safety climate of construction workers. To Cooman & Vleugels (2002) the idea of person-environment fit emphasizes the unique role the social and work environments play in shaping individual behavior. With respect to basic principles, the theory believes that the person and the environment together predict human behavior better than each of them does separately. This no doubt refers to the compatibility between individuals and their environment (Van Vianen, 2018), and in the present study the interaction between the workers and perceived safety climate of the enterprises. Human beings are safety-seeking mechanisms and construction workers particularly through education will seek safe havens, perceived safety climate that match with their safety needs in order to function maximally. With psychosocial risk management strategies, safety education enables workers to manage psychological risk factors, reduce stress and adapt appropriately to their work environment. It is likely that this leads to satisfaction and motivation of workers as well as respect of safety values in the construction companies. To Van Vianen (2018, 76) “fit theory proposes that outcomes are most optimal when personal attributes (needs, abilities, values) and environmental attributes (supplies, demands, values) are compatible regardless of the level of these attributes.” This draws in the notion of congruence, indicating the degree of match between the construction workers and their environment. This is evident with the proposition of Van Vianen (2018) that outcomes in any venture is most optimal when personal and environmental attributes are compatible despite their degrees. Thus, when the attributes of construction workers are compactable with perceived safety attributes of the organizations, they will likely perform better in terms of safety and overall performance of the organization. Considering the importance of safety climate as one of the factors involved in preventing and reducing occupational accidents and also considering its positive impact on workers’ safety performance (Omid, Eskandari & Omidi, 2021), this study intends to find out the contributions of safety education to perceived safety climate of employees in construction companies. The interest of the study is to obtain results and ensure safety of construction workers operating at high risk.

3. Methodology

3.1. Design and Participants

- Employing a quantitative design, the study was realized with workers of Edge and BUNS Construction enterprises in Mezam Division, Cameroon. The companies carry out road constructions in Bafut, Bali, Bamenda Ι, ΙI, III, Santa and Tubah subdivisions. These are employees exposed to hazards with experiences of psychological hazards and knowledge of safety management plan of the companies. A sample of 318 workers in the road construction sites and building Departments were recruited in Bamenda and Nkongbou construction sites in Edge (N=147) and BUNS (N=171) Companies. Furthermore, the sample constituted 222 males (69.8%) and 96 females (30.2%) indicating low rate of participation of females in the robust sector. The investigators dealt directly with workers onsite to obtain information. In terms of employment status, participants comprised permanent workers (42.8%), contract workers (54.7%) and apprentices (2.5%). Majority of participants were holders of Ordinary Level Certificates (24.8%), followed by Advanced Level (20.4%), Higher National Diploma (19.5%), Bachelor’s degree (19.9%%), First school leaving certificate (10.7%), Masters (4.1%) and PhD (1.6%). Due to the nature of activities of the workers, perceived pressure on work schedules and nature of operations, purposive and convenient sampling techniques were deployed to recruit participants in order to collect the necessary information that will determine the link between safety education and perceived safety climate of the companies.

3.2. Data Collection Measures

- In order to collect information for the study, quantitative measures were used in the process and a close-ended questionnaire was used. The primary section of the instrument was designed to collect socio-demographic information on sex of participants, age, educational qualifications, longevity at work, posts of responsibility and occupational activities. The self-report scale for Safety Education was designed to measure level of safety education in the companies, and indices were drawn from literature (DeJoy et al. 2004; Gyekye & Salminen 2009; O’connor et al. 2014). The measure included 10 items including safety awareness, safety education, safety training, practical lessons, safety policies, safety messages, safety rules, use of PPE, safety updates and sanctions. Sample items included, “Safety policies are made known to workers” and “Workers receive lessons on the use of personal protective equipment.” The items were coded with four possible alternatives “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “agree” and “strongly agree” with numerical values of 1, 2, 3 and 4 respectively. Higher scores indicated a high value placed on safety education and practice by the enterprises, while lower scores implied the reverse. The internal reliability analysis for the measures of safety education was performed (M = 38.81, SD = 118.025, α = 0.903), and determined with Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.90, which was excellent (George and Mallary, 2003), and collected reliable information from the participants.The measure for Perceived Safety climate was defined as shared perceptions of workers on safety related practices, and measure was adapted from the Nordic Safety Climate Questionnaire (Kines et al., 2011), and particular interest was on the safety climate dimension. The sub-scale had 10 items with indices including Safety priority, safety concerns, management commitment, skills development, safety precautions, workers’ commitment, provision of PPE, safety communications, safety consultations, safety system. Sample items were, “Management considers workers’ safety a priority” and “Staff consciously use safety equipment.” The items were coded with four possible alternatives “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “agree” and “strongly agree” with numerical values of 1, 2, 3 and 4 respectively. The internal reliability analysis for the measures of perceived safety climate was performed (M = 35.48; SD = 136.067, α = .948) and the reliability, calculated as Cronbach’s alpha, was excellent for the two main scales (α =0.92), safety education and perceived safety climate, suggesting that information collected from participants was reliable. The process of conducting the study was guided by the ethical standard of the American Psychological Association (APA) where the codes were applicable.

4. Results

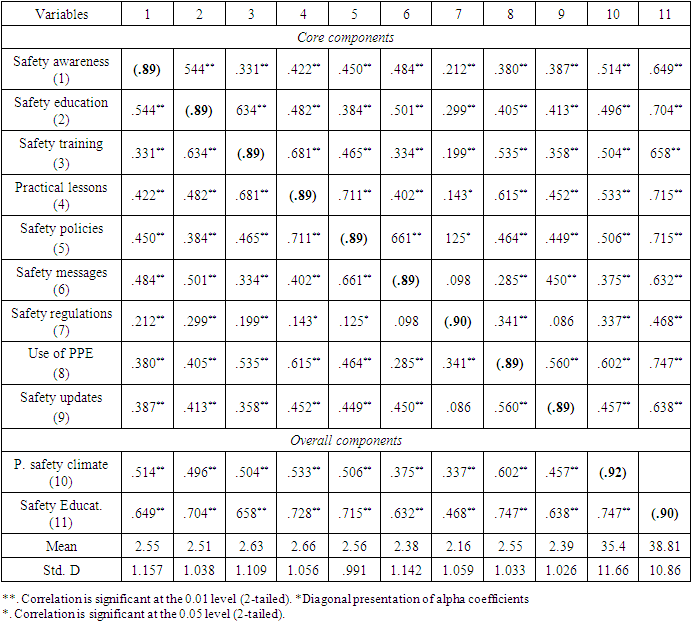

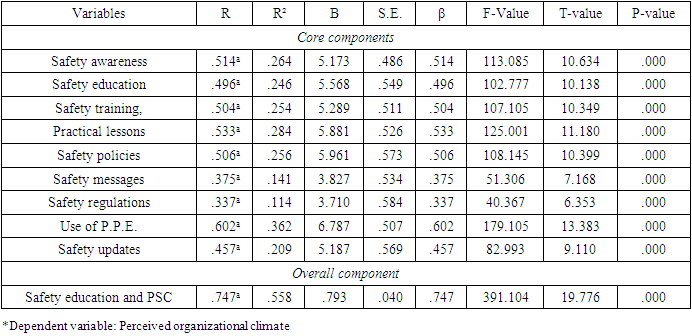

- Descriptive, bivariate correlation analysis among study variables and test results have been presented (Table 1). The bivariate correlations between the indices of safety education and the outcome variable, perceived safety climate were all significant. From the analysis, it was observed that most of the relationships were significant at P<0.01, with moderate correlation coefficients.

|

|

5. Discussion

- Within the context of psychosocial risk management plan, the study investigated safety education as a determinant of perceived safety climate of construction workers and results were significant. This concurs with the findings of Tobi et al. (2001) on empowerment-based hazardous materials training programs and improved work environment, advocating for workplace health and changes in safety practices. The benefits of education to workplace safety transcends the building of safety climate to management commitment and motivation in high risk work settings. This is achievable in the construction sector especially when much is done on education and awareness on safety policies, and strategies in delivering safety messages. Results are also consistent with Gyekye & Salminen (2009) on significant results on the relationship between educational attainment and safety perception, compliance to policies and accident frequency. Findings corroborates the claims of the companies that the institutions have safety policies, and risk mitigation strategies to ensure a conducive safety climate. The understanding is that safety education is critical to safety climate, sense of security of workers and productive work behaviors and this is the rationale for empowerment of workers in these companies even if the current level is not satisfactory. In the same vein, findings are consistent with Omid et al., (2021) on training classes for workers and safety discussions, importance of workplace safety, safety performance and promotion of safety climate factors. Consequently, the proactive provision of safety information to employees is capable of answering management questions with respect to the demands of hazards and organizational climate. It has been noted that the role of safety climate is capable of preventing, reducing occupational accidents, increasing safety performance, safety attitude, safety communication, safety policy and safety participation (Guo et al., 2020), Omid et al., 2021). These are factors essential in work performance with great implications on the reinforcement of the current level of safety education in the construction companies. Despite the fact that conceptualizations and findings are dominantly beyond local contexts, learning from psychosocial risk management particularly in safety education are applicable to building sustainable safety climate of the companies. Findings suggests that psychosocial risk management plans are adaptive strategies designed to mitigate risks in general and occupational risks in particular towards the realization of strategic business objectives of the organizations. Against expectation, the results of Agumba et al. (2018), were in disaccord with the present study since safety empowerment failed to determined health and safety elements of the organization. This might have been due to low level of safety education, interest of participants, contexts of training, skills and training approaches. It is evident that where empowerment does not meet the necessary conditions and approaches, outcome will not be satisfactory. The reports also contradict Fomba (2020), where workers embraced fatalistic practices as safety measures in traditional work setting as a measure of safety motivation and work performance. Although this was in a culturally addicted milieu, workers had been socialized into fatalistic beliefs as safety values in their operations. Despite the some questions on the effect of training as a measure of perceived safety climate, there are generally optimistic perceptions that when the level of safety education is high it will lead to a corresponding improvement in the level of safety climate in the construction sector. This is in accord with Griffiths (2010) that safety education at work can have favorable outcomes at employee level such as job satisfaction, increased well-being and at organizational level in terms of commitment, productivity, decreased absence and turnover behavior. This concurs with results of the current investigation that safety education as a psychosocial risk management plan stands to improve perceived organizational climate and work behaviors of the construction workers.

6. Conclusions

- Recognising the fact that safety climate refers to workgroup members’ shared perceptions of management and workgroup safety related policies, procedures and practices (Kines et al., 2011), implementation is naturally a cultural practice in construction companies but for the perceived importance and mutual support by workers and management. This equally builds on the premise that safety climate constitutes a special form of organizational climate rooted in individual perceptions of the importance of safety and directs the actions of employees, working groups and individual attitudes towards safety (Omid et al., 2021). This at the same time questions the use of physical risk management system alone as a response to psychological risk factors. This is why psychosocial risk management and safety education in particular remains a core facility capable of ensuring safety climate and should be implemented and supported by management, workers and the government in high risk work stations. The findings stand to contribute to the body of knowledge in the domain of OSH, particularly in local context where legislation has weak enforcement mechanisms. Nonetheless, Government authorities and safety officials stand to learn about the critical role of safety education in preserving safety climate with accompanying work-oriented behaviours. This concurs with the recognition that employees awareness on basic safety, workplace hazards, associated risks, response strategies and use of safer methods, techniques, processes and safety culture (Silva et al., 2004) can lead to competitive edges in promoting safety performance at construction sites. Consequently, Government and safety officials need to reiterate existing legislation on health and safety at work. Perceived safety climate is also a source of motivation, commitment and emotional stability to workers in high risk work sites, and it is essential that safety education should be reinforced to enhance safety performance. The situation is even more critical in times of crisis with heightening pressure from organizational and extra-organizational stressors (Fomba et al. 2021), and this goes a long way to compound the of construction workers experiencing high level environmental risk factors. Workplace legislations on health and safety have been left at the mercy of manipulations by management of enterprises and this is drawn from little of no control, monitoring and evaluation from Government officials, notwithstanding that fact that safety is a sensitive factor and concerns the life of employees. Although Cox (2007) observed that strict laws do not exist when it comes to creating a safe place for workers in road construction, the situation in Cameroon is different but for strict follow-up that had rendered available instruments cosmetic. With the current findings, stakeholders can forge ahead responsive strategies that will promote safety perceptions and attitudes to create awareness programs that will foster safety climate. This does not exclude organisation-specific communication strategies that will positively impact on safety attitudes and job behaviours of employees. One thing needful in promoting safety climate is to recognise that roles of inspection exercises, supervision of safety measures, awards to complaints as well as punish defaulters at all levels.The use of the Person-Environment (P-E) Fit theory (Van Vianen, 2018) to appreciate the link between safety education and perceived safety climate of construction workers had demonstrated relevance in local contexts, and the culture fit-ness of the model in explaining the contributions of psychosocial risk management plan to the enhancement of safety climate in high risk work sites. Therefore, the more the construction workers learn about safety matters, they more their working environment will be made safer for work. As an imported model local and progressive safety values needs to be integrated into the latter to produce an integrative model capable of enhance learning and maintaining a sustainable safety climate for construction companies. Another interesting observation is on the measure of perceived safety climate adapting items from the NOSACQ-50. Kines et al. (2011) recalled that the NOSACQ-50 was developed based on organizational and safety climate theory, psychological theory, previous empirical research, empirical results acquired through international studies, and a continuous development process. The instrument, though items adapted, were valid and reliable considering that the internal consistency measure for the overall component had an aggregate alpha of 0.92, which to George & Mallery (2003) was excellent. This shows that the information collected to test the contributions of safety education to perceived safety climate was trustworthy, since the measure for safety education, locally developed was also excellent. In recent years awareness of the importance of safety performance of organizational, managerial and social factors has increased and offers a route for safety management, complementing the often predominant engineering approach (Kines et al., 2011). This is an opportunity for enterprises, safety managers and officials to promote safety in construction companies and this starts with appropriate safety education as a measure of psychosocial risk management. Although the study sample was drawn from two local construction companies, the results are generalizable to them and similar companies under the same conditions and culture of operations since findings constitute useful directions for action. Apart from education of workers management should ensure an enabling environment that empowers workers on safety issues and also monitor the safety climate of the company. The degree of exposure of workers particularly in construction industries in local contexts has been perceived as being beyond occupational exposure limit and although workers share the blame, some management do not have safety policies nor provide the necessary PPE for their employees. Safety Departments or Safety Units are indispensable in construction companies where trained officials stand to harness safety climate of their organizations to reduce hazards, accidents, wanton compensation and boost the morale of workers in safety performance. It is also a strategy to promote the identity and corporate image of the company. These competitive edges can only accrue to the companies and employees when the necessary risk mitigation strategies are recognized as valuable and implemented. This justifies the role of psychosocial risk management strategies in enhancing the safety climate of organizations, which stand to reinforce physical/material safety strategies that have been predominant in construction companies.

6.1. Limitations and Future Research Directions

- Despite the contributions of the current study in safety education as a dimension of psychosocial management risk plan to perceived safety climate of contraction workers, there are some practical difficulties that were encountered and might have affected expected results. There is limitation in terms of scope considering that the study was carried out only in the construction sites of two companies and in Mezam Division, North West Cameroon. Moreso, the number of participants were limited and could cause a big problem of representation and generalization of results to other enterprises in the sector. The study concentrated only on local companies since foreign companies had abandoned the project due to insecurity arising from socio-political crisis and this implies the use of research results only to the local companies. The study employed only quantitative methods with questionnaire as data collection instrument, which is dogmatic and there was no opportunity for triangulation of methods and results to ensure ecological validity. This might have also affected the outcome and possible implementation of the study. This investigation was conducted in times of socio-political crisis in the area of study and as the only operating companies, the study became resource intensive as the researchers had to overcome nontraditional barriers to obtain authorization and in collecting data from Edge and BUNNs. These really put constrains on a relaxed study atmosphere for the researchers and participants as well as the utility and generalization of the results. The construction sector is rigorous with high intensity operations that often lead to pressure and stress on workers, and this may affect the quality of information considering that participants may not have enough time to reflect on items on the questionnaire, and this may lead to response set especially social desirability bias. It is therefore necessary to employ a degree of caution in consuming the results of the study without taking into consideration the challenges encountered.With respect to the weaknesses of the current study on safety education as determinant of perceived organizational climate in Mezam, Cameroon, a number of gaps were observed in the approach of conducting the study, and this has to be taken into considerations with future research initiatives. Future studies require expansion in terms of area of study, enterprises and participants. It would be very useful to conduct a large study on safety education and perceived safety climate at construction sites and the dimension should include the role of the Government officials, particularly labor inspectors in enforcing policy plans such as safety education. Future studies should extend to safety training, attitude and use of PPE in the workplace, risk identification and perceived safety climate. These studies should use mix method design, where the use of questionnaire will include interview, observation and focus group discussion and this will give opportunity to triangulate methods, data sources and results. Therefore, the approach will be able to capture qualitatively the experiences and perspectives of employees with both positive and negative opinions and their core interest will be documented. It had been recognized that research is an expensive venture and enough resources should be budgeted for future research studies in construction companies in order to use the varying approaches within an appropriate period. This is in order to obtain relevant data and results that will be more representative of the challenges faced on ground for necessary responsive solutions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML