-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2023; 13(1): 18-27

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20231301.03

Received: May 1, 2023; Accepted: May 24, 2023; Published: May 29, 2023

Thinking about Existential Questions in a Liberal Arts Class and Student Adjustment in University: Preliminary Findings

Yusuke Murakami

Faculty of Letters, Kansai University, Suita, Japan

Correspondence to: Yusuke Murakami , Faculty of Letters, Kansai University, Suita, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study aims to develop a liberal arts class designed to consider meaning-oriented education (i.e., addressing the theme of existential questions) at the university. This study investigates (a) the relationship between university students' thinking about existential questions through a target class and student outcomes (e.g., the existence of task and purpose as university adjustment or intention to take a similar class in the next semester), and (b) a potential moderated effect of the deep approach to learning on these relationships. In total, 188 university students (Mage = 19.27 years, SD = 1.23; Men = 70, Women = 118) completed self-rating scales after completing the target class. A paired t-test showed that participants thought about existential questions more in the target class than in the non-target classes they took during the same semester. A series of hierarchical multiple regression analyses revealed that there was no moderated effect of the deep approach to learning, and that thinking about existential questions in this target class was significantly related to the existence of task and purpose (β = 0.26, 95% CI [0.09, 0.43]) and intention to take a similar class in the next semester (β = 0.67, 95% CI [0.48, 0.87]). The need for examining the effectiveness of this education through a more sophisticated research design is discussed.

Keywords: Spirituality, Personal growth, Humanities education

Cite this paper: Yusuke Murakami , Thinking about Existential Questions in a Liberal Arts Class and Student Adjustment in University: Preliminary Findings, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2023, pp. 18-27. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20231301.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- One of the most important issues in spirituality education is to address existential questions such as the meaning of life (Nakagawa, 2005). Palmer (1998/1999) has argued that such spiritual (deep) questions are already embedded in the situation of learning, and helping young people find these questions is called spiritual mentoring. Furthermore, supporting or creating opportunities for students to construct a frame of meaning contributes to their spiritual development (Kessler, 2000). However, despite these practical suggestions, there are few concrete examples of education addressing these big questions and evidence of their effectiveness. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to develop a liberal arts class designed to consider the big questions of life at the university, and to examine the relationship between university students’ thinking about these questions in the target class and student outcomes, utilizing a preliminary design without a control group.

1.1. Big Questions and University Students

- For university students, the big questions of life are one of their major primary concerns. Big questions are defined as the fundamental issues of life, such as the nature of the self, world, and transcendent existence, or the meaning of life, death, love, and value (Murakami, 2022). In Murakami (2016), approximately two-thirds of the studied college students indicated that they would like to think about and learn about the questions pertaining to the importance of life, happiness, and meaning in life. In a large-scale survey of college students in the United States (U.S.), freshmen students who scored higher in spiritual quests cited finding meaning in life as an important reason for attending college (Astin et al., 2011); furthermore, the students’ mean scores of meaning-making and spiritual quests increased over three years (Riggers-Piehl & Sax, 2018).The exploration of the big questions has been found to impact college students’ outcomes, but there is no consistent evidence that these questions bring about positive effects. For example, Astin et al. (2011) have reported that spiritual quests are positively weakly associated with leadership skills and intellectual self-esteem but negatively weakly associated with psychological well-being and overall satisfaction with college. In a series of studies about spiritual intelligence, the critical existential thinking subscale was found to be a positive significant predictor of depression and anxiety in university students in the U.S. (Giannone & Kaplin, 2017) but not a significant predictor of well-being in post-graduate students in India (Sood et al., 2012).

1.2. Necessity for Meaning-oriented Classes in Higher Education

- Considering that thinking about big questions is not always a positive experience for university students, there is a growing need for educational initiatives that help them think about and construct answers to these questions. Because thinking about the meaning of life often inspires anxiety or confusion (Zhang et al., 2018), it is important for students to develop and order their own ideas regarding these questions by being exposed to a variety of views within a structured framework. In the higher education context, practices such as the SEE Process (imagination-centered education; Manning, 2017) and Big Questions program (first year orientation program; Nair et al., 2007) have been developed to promote students’ meaning-making. It has been shown that spiritual pedagogies (e.g. meditation) or spiritual interactions (e.g. encouraging discussions of religious / spiritual matters or ethical issues) are significant positive predictors of meaning-making and spiritual quests (Astin et al., 2011). If some students would like to face the big questions during their college or university careers, taking a meaning-oriented class would satisfy their spiritual needs and enhance their sense that they are growing in a suitable environment. Thus, this type of education might contribute to their subjective feeling of the person-environment (P-E) fit in university. The P-E fit is defined as “the congruence, match, similarity, or correspondence between the person and the environment” (Edwards & Shipp, 2007, p. 211). Moreover, the need-supplies (N-S) fit, an aspect of academic P-E fit, predicted academic satisfaction (Li et al., 2013).Taking a target class to consider the big questions would increase students’ motivation for further exploration after finishing the class. Because big questions are of vital importance and “reveal the gaps in our knowledge” (Parks, 2011, p. 178), once provided the opportunity to consider these questions, it is expected that students will be more eager to further explore these questions. For example, it was found that the frequency of students thinking about a big question in a university class is positively associated with positiveness in learning from the learning motivation scale after controlling for trait novelty seeking (Murakami, 2021).Although such meaning-oriented education is already being offered at some universities (e.g. Manning, 2017; Nair et al., 2007), there are no studies that have attempted to empirically examine the effectiveness of such education. This study aims to fill this gap by developing a meaning-oriented target class and quantitatively investigating the benefits of this approach.

1.3. The Deep Approach to Learning as a Potential Moderator

- As mentioned above, there was no consistent association between students considering the big questions and college student outcomes in prior studies. One possibility for this is that there may be a moderating factor in this relationship. This study focuses on the deep approach to learning as a moderator to extend the investigation of the relationship between big questions and university adjustment. The deep approach to learning includes seeking meaning in learning (Entwistle & Peterson, 2004), and it is defined as “the intention of students to understand information by relating ideas to each other and using evidence” (Lindblom-Ylänne et al., 2019, p. 2184). Features of this approach include, for example, “relating ideas to previous knowledge and experience,” “looking for patterns and underlying principles,” “checking evidence and relating it to conclusions,” and “engaging with ideas and enjoying intellectual challenges” (Entwistle & Peterson, 2004, p. 415). The deep approach to learning has been found to have positive but small associations with student Grade Point Average in a meta-analysis (Richardson et al., 2012), and a positive correlation with daily action connected to future life in university students (Kawai & Mizokami, 2012).In learning situations, when considering the big questions, reflecting on one's own life experiences and making connections to knowledge learned in other classes may help construct more comprehensive answers to the questions. For example, when considering the important values in their lives, if students can easily reflect on their own daily lives and make links with what they have learned in other classes (e.g. learning about social problems or ethical issues), they could devise their own satisfactory ideas about these values. Although big life questions essentially make one reflect their way of life, the more frequently and regularly a student engages in the deep approach to learning, the stronger their connection between considering these questions and a sense of adjustment.

1.4. The Present Study

- In summary, I focus on humanities education in the university context and attempt to identify and justify the benefits of using a meaning-based approach. In particular, the purpose of this study is (a) to develop a class that will help students explore big questions and (b) to examine the relationship between students' thinking about big questions and student outcomes (i.e. university adjustment and intention to take a similar class in the next semester). If considering big questions in a structured environment helps meet students' needs, then the frequency of considering these questions and the sense of adjustment or intention to take a similar class are expected to be positively related. Additionally, this study examines whether these associations are moderated by the deep approach to learning.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

- Participants were recruited online through the learning management system of the university after the last session of the target class. This target class was the liberal arts class designed to consider big life questions. Participants volunteered and were not compensated for their participation. Of the 478 students registered for the target class, 207 volunteered to participate in the survey. Nine-teen participant surveys were excluded from the analyses because the attention check question was answered incorrectly. Thus, the total sample included 188 university students (Men = 70, Women = 118) in urban areas of Japan, aged between 18 and 23 years (Mage = 19.27 years, SD = 1.23). Regarding the class standings of participants, 50.5% of the sample were freshmen, 19.7% were sophomores, 23.4% were juniors, and 6.4% were seniors. Faculty affiliation of the participants was 52.7% Sociology; 28.7% Business and Commerce; 13.3% Economics; 3.2% Chemistry, Materials and Bioengineering; 1.1% Engineering Science; and 1.1% Environmental and Urban Engineering. Those who agreed to participate were required to check off a box indicating their consent. Ethics approval was obtained from the relevant university board (HLE-220402-A).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic Variable

- The first section of the questionnaire asked participants to provide their demographic information, including age, grade, gender, and faculty affiliation. To check for duplicate responses, their student ID numbers were collected; however, only a part of the ID number was collected to ensure the anonymity of the participants.

2.2.2. Big Questions

- The Search of Meaning in Life subscale from the Big Question Scale (BQS; Murakami, 2012) was modified to measure the frequency with which big questions were thought about in the target class (BQS-ML-TC) or in all other classes taken by the participants during the same semester (BQS-ML-OC). This sub scale consists of six items regarding value, happiness, meaning in life, self, facing fear, and love. Participants indicated their level of agreement with statements on a 6-point scale ranging from “1 = disagree” to “6 = agree.” An example item is “Through this class (all other classes except this class in BQS-ML-OC), I’ve thought about the question, ‘does life and living have meaning or purpose?’, in my own way.” Cronbach’s alphas were .90, 95% CI [.87, .92] for BQS-ML-TC, and .95, 95% CI [.94, .96] for BQS-ML-OC, indicating sufficient internal consistency.

2.2.3. Approach to Learning

- The eight item Deep Approach to Learning subscale from the Learning and Studying Questionnaire (Entwistle et al., 2002), translated into Japanese (Kawai & Mizokami, 2012), was used to assess the deep approach to learning regarding participants’ academic work. Participants indicated their level of agreement with statements on a 7-point scale ranging from “1 = disagree” to “7 = agree.” An example item is “I try to make sense of things by linking them to what I know already.” Cronbach’s alpha was .80, 95% CI [.75, .84], indicating sufficient internal consistency.

2.2.4. University Adjustment

- The eight item Existence of Task and Purpose subscale from the Subjective Adjustment Scale for Adolescents (Okubo, 2005) was used to measure the subjective feeling of P-E fit in college students. Participants indicated their level of agreement with statements on a 5-point scale ranging from “1 = disagree” to “5 = agree.” An example item is “I feel that I can grow (at the university).” Cronbach’s alpha was .85, 95% CI [.81, .88], indicating sufficient internal consistency.

2.2.5. Intention to Take a Similar Class in the Next Semester

- An original item was developed to ask participants if they would like to take a similar class, like the target class, in the following semester that is designed to help them think about their way of living. The item is “In the next semester, would you like to take a class that thinks about the way of living, such as this class?.” Participants indicated their level of agreement with statements on a 7-point scale ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree.”

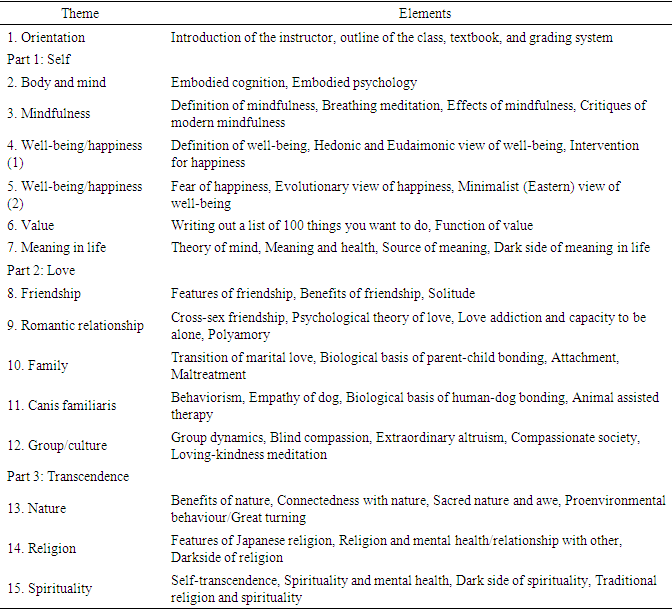

2.3. Procedure

- The target class was a remote class delivered on demand for the purpose of infection control during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because the number of applicants exceeded the maximum enrollment limit, participants for the class were selected by lottery.As shown in Table 1, the course consisted of 15 lectures, and a textbook was assigned. The first three and 11th lectures were video-on-demand lectures because these were not included in the textbook. Lectures 4–10 and 12–15 provided explanations of the topics in the textbook (Murakami, 2022) and introduced research findings not included in the textbook. After viewing the lecture videos, students took a quiz to check their understanding of the content of the class. Following this, students voluntarily filled in class evaluations, comments, and questions at the end of every class. Short responses for their comments and questions were presented at the beginning of the following week's class to create opportunities for exposure to different ideas.

|

2.4. Analyses

- First, a paired t-test was conducted to determine whether the target class developed in this study encouraged participants to think about the big questions more than their non-target classes. Correlations among the variables were then calculated. To test this hypothesis, a series of hierarchical multiple regression models were conducted that included the Existence of task and purpose subscale, measuring the intention to take a similar class as a dependent variable. In Step 1, the demographic variables (age, grade, and gender) and BQS-ML-OC were included. Step 2 added the Deep approach to learning and BQS-ML-TC variables. Step 3 added the interaction variable of Deep approach to learning and BQS-ML-TC. Except for the Step 1 model (dependent variable: Existence of task and purpose), all models did not meet the assumptions of homoscedasticity based on the Breusch-Pagan test (ps < .02); hierarchical multiple regression was conducted by calculating the robust standard errors with the HC3 method to avoid inflation of a type I error. R (ver.4.2.0; R core Team, 2022) and R studio (RStudio Team, 2022) were used to perform all the statistical analyses. All analyses used psych (Revelle, 2022), smplot (Min, 2022), apaTables (Stanley, 2021), effsize (Torchiano, 2020), olsrr (Hebbali, 2020), and jtools (Long, 2022) statistical packages in R. Statistical significance was set at a p value < .05.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

- As shown in Figure 1, the results of the dependent (paired) sample t-test indicate that there are significant differences in the degree of BQS-ML between the target class (M = 4.84, SD = 0.87) and non-target classes (M = 3.57, SD = 1.40), t (187) = 12.60, p < .001, mean difference = 1.27, 95% CI [1.07, 1.47], d = 1.06, 95% CI [0.85, 1.27].

| Figure 1. Violin Plot of BQS-ML in the Condition of Target Class and Other Classes (Note. Error bar shows 95% confidence interval for mean.) |

|

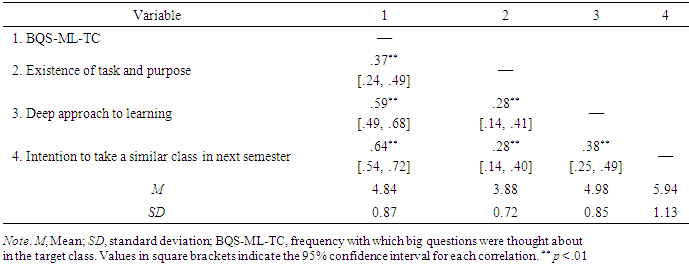

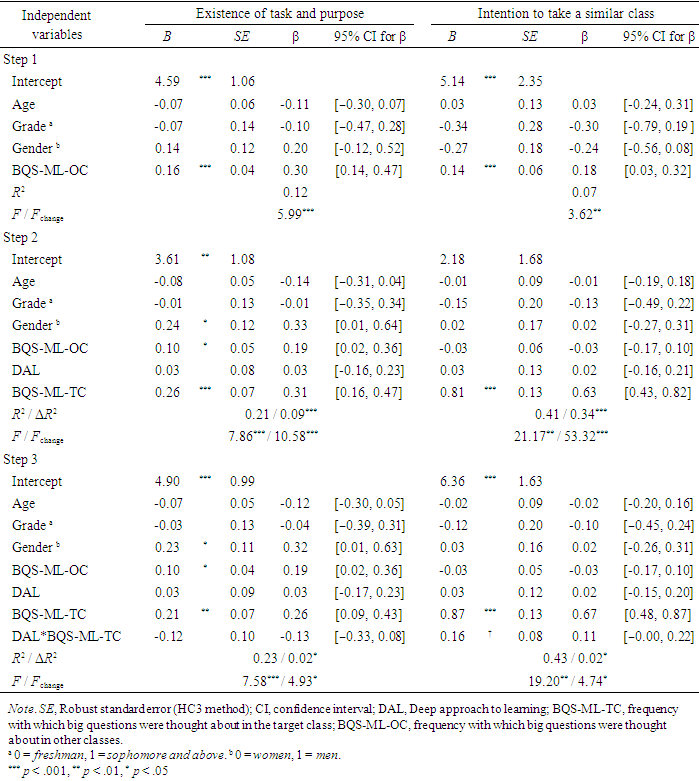

3.2. Main Analyses

- To test the hypotheses, a set of hierarchical multiple regression models were conducted. The results are shown in Table 3.

|

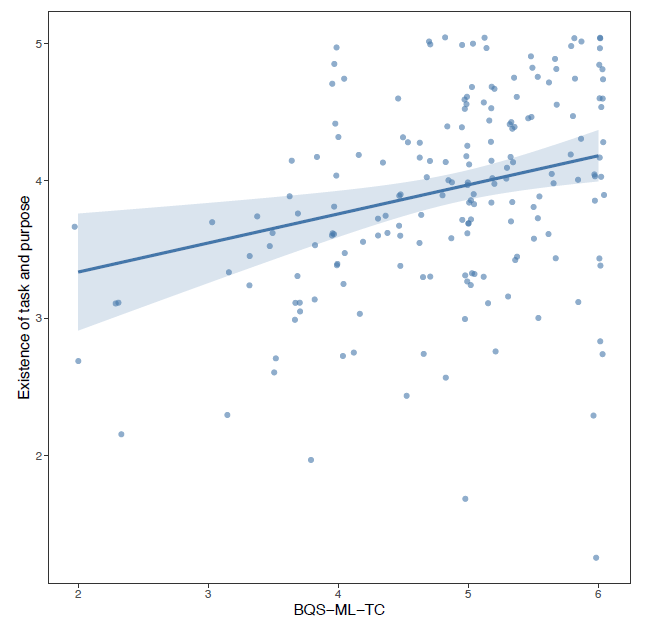

3.2.1. Existence of Task and Purpose

- At first, all three models were significant, however, the change in R2 indicated that the Step 3 model significantly improved the model fit. Within this model (R2 = 0.23, F (7, 180) = 7.58, p < .001, adj. R2 = 0.20, VIFs < 2.35), there was no significant interaction between Deep approach to learning and BQS-ML-TC (β = -0.13, 95% CI [-0.33, 0.08]). The results also indicate that gender (β = 0.32, 95% CI [0.01, 0.63]), BQS-ML-OC (β = 0.19, 95% CI [0.02, 0.36]) and BQS-ML-TC (β = 0.26, 95% CI [0.09, 0.43], Fig. 2) were significantly related to Existence of task and purpose.

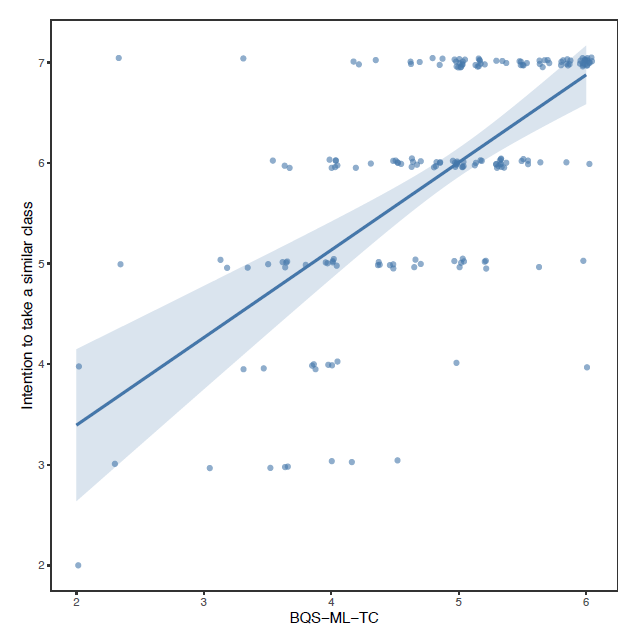

3.2.2. Existence of Task and Purpose

- Initially, all three models were significant, however, the change in R2 indicated that the Step 3 model significantly improved the model fit. Within this model (R2 = 0.43, F (7, 180) = 19.20, p < .001, adj. R2 = 0.41, VIFs < 2.35), there was no significant interaction between Deep approach to learning and BQS-ML-TC (β = 0.11, 95% CI [-0.00, 0.22]). The results also indicated that BQS-ML-TC (β = 0.67, 95% CI [0.48, 0.87], Fig. 3) was significantly related to Intention to take a similar class in a next semester.

4. Discussion

- The main purpose of this study was to design a liberal arts class that considers the big questions and to determine whether students' thinking about big questions through this course is associated with a sense of college adjustment and a further motivation to take a similar class. Through the survey, it was found that the frequency of considering big questions in the target class was related to the presence of a task or purpose and intention to take a similar class in the next semester. However, because this was a preliminary study, its conclusions should be considered in light of some limitations.

4.1. Meaning-centered Practice

- The present study shows that participants thought about big life questions more in the target class than non-target classes they took in the same semester. While previous studies have only reported meaning-centered education in case studies (e.g. Manning, 2017), this study extends this literature to quantitatively demonstrate the effectiveness of such education. In addition, this study shows that it is possible to provide an opportunity to think about big questions, even in a non-contact online class conducted under COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. However, it is important to note that only about half of the total number of students who took the target class responded to the survey, which may have caused sampling bias. Because these participants may have been active learners to begin with, they may have more actively engaged in the class goal of considering big questions than their peers who did not volunteer for participation, thus skewing the data.

4.2. Big Question and Student Outcomes

- The most important finding of this study is that I was able to empirically clarify the relationship between thinking about big questions in the target class and student outcomes. That is, as expected, the frequency of thinking about big questions in the class was positively related to students’ sense of adjustment. In this study, gender, age, and frequency of thinking about the question in other classes were controlled. Interestingly, the experience of thinking about big questions in other classes, a controlled variable, was positively associated with the Existence of task and purpose subscale. This result suggests that the experience of thinking about big questions in college classes can be a predictor of university adjustment. These findings are consistent with the findings of previous studies in which the cultivation of spirituality was found to be important for college students’ development (Astin et al., 2011), and N-S fit predicted academic satisfaction (Li et al., 2013).This study further shows that thinking about big questions is positively associated with the intention to take a similar class in the next semester. This result provides preliminary evidence that the more students face the big questions of life in the target class, the more they want to register for meaning-oriented education in the future. This is consistent with the argument of Parks (2011) who has suggested that big questions could reveal the gaps in one’s knowledge. However, further investigation is needed to ascertain the robustness of these results.Furthermore, an unexpected finding is that there was no interaction between the frequency of thinking about big questions and the approach to learning in this study. One possible explanation for this result is that the impact of class content or method was relatively strong. Regardless of whether they utilize deep engagement with learning, students were invited to reflect on their big life questions in this class. For that reason, the type of approach to learning could not be a moderated variable in this study. In a previous study (Murakami, 2021), although trait curiosity was not a significant moderated variable, there was a positive association between thinking about big questions and university adjustment. Considered together, these results suggest that thinking about big life questions in a class may provide students with a certain sense of growth, regardless of the learning-oriented trait or strategy.

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

- First, this is a cross-sectional preliminary study, which only reveals associations among variables at a single point in time and cannot indicate causal relationships. More evidence is warranted before reaching definitive conclusions about the effects of meaning-oriented education on student outcomes. Future research should use more sophisticated research designs, such as setting up a control group or using a longitudinal study design.Second, the data were collected through limited sampling. The number of students who participated in this study was less than half of the total number of students who took the target class. Therefore, it is possible that the participants in this study were sincere or cooperative. It is also possible that the participants were originally interested in this type of introspective educational content, even though they were selected by lottery. These factors may have contributed to bias in the findings of this study. It is important to consider an analytical design that excludes bias as much as possible, for example, by conducting an analysis using personality characteristics as covariates.Third, because this study was conducted on Japanese university participants, the generalizability of the results should be considered cautiously. According to a dialectical model of meaning in life (Steger et al., 2008), the functions of the search for meaning in life depend on cultural variations. In particular, the search for meaning in life is not necessarily a negative experience for Japanese people. Additionally, the content of this target class is influenced by Eastern philosophy and Japanese religious perspectives, such as Shintoism and Buddhism, and it has little to do with religious perspectives from other cultures, such as Christianity and Islam.

5. Conclusions

- Despite the above limitations, the findings of this study advance the research literature on the big questions of life. First, this study shows that dealing with the big questions in the structured form of a class could contribute to the well-being (i.e. university adjustment) of college students. Secondly, this study shows that earnestly addressing spiritual questions through meaning-oriented classes might be a predictor of learning motivation for students. I will continue to explore further the role that meaning-oriented practice can play in making students’ college lives meaningful.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I gratefully acknowledge students for their cooperation with this survey.I would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Disclosure

- I received a portion of sales in the form of textbook royalties.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML