-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2022; 12(1): 16-22

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20221201.03

Received: Jul. 27, 2022; Accepted: Aug. 12, 2022; Published: Sep. 23, 2022

Stress at Work and Professional Satisfaction Among Health Care Staff

Ouyi Badji1, Anagba Kokuvi Déogratias2

1Department of Applied Psychology at the Faculty of Human and Social Sciences, Université de Lomé, Lome-Togo

2Ministry Delegate to the Presidency of the Republic, in Charge of Financial Inclusion and the Organization of the Informal Sector, Lome-Togo

Correspondence to: Ouyi Badji, Department of Applied Psychology at the Faculty of Human and Social Sciences, Université de Lomé, Lome-Togo.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

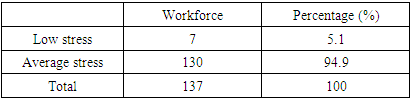

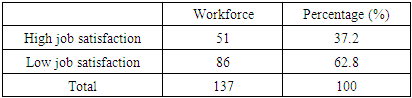

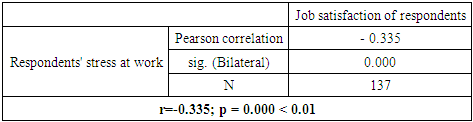

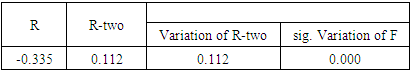

This study aims to highlight the relationship between stress at work and job satisfaction. This manuscript analyses the imbalance between the work related requirements (source of stress at work) and the available resources within a University Hospital Center. In addition, this manuscript goals are to determine the impact of stress at work on the level of job satisfaction of the doctors and nurses of this center. We collected data from 137 individuals (48 doctors and 89 nurses). We used quantitative (scales) and qualitative (interviews) methods. The statistical analysis (Pearson correlations and regressions through the SPSS software) of the quantitative data and the content analysis of the interviews conducted enabled us to obtain interesting results. A significant relationship exists between stress at work and job satisfaction (r = -0.335; p = 0.000 < 0.01). The results also show that respondents are dissatisfied (62.8%), due to a high level of stress at work (94.9% of respondents are moderately stressed).

Keywords: Stress at work, Job satisfaction, Working conditions

Cite this paper: Ouyi Badji, Anagba Kokuvi Déogratias, Stress at Work and Professional Satisfaction Among Health Care Staff, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 12 No. 1, 2022, pp. 16-22. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20221201.03.

1. Introduction

- The transition from the classic production line to autonomous teams, the reorganisation of workstations, and the empowerment of teams, the quality approach requires physical and intellectual efforts [1]. This mental workload is thus tending to increase in many companies, due to several factors. The most common of these factors are more intensive work combined with the need for strict compliance with deadlines, the need to take responsibility for decisions in a highly restrictive or demanding environment, the absence of hierarchical recourse, and confrontation with multiple incivilities from users or customers, etc. [2]These new dynamics in the world of work produce known secondary effects in the form of new risks in the field of safety, health, and psychosocial at work. Alongside biological and chemical risks, psychosocial risks appear to be major. They relate to situations likely to affect the mental health of the worker and his physical integrity. These include situations like moral and verbal harassment, forms of violence, professional suffering, depression, stress, etc.Among these risks at work, stress is known to be the most important to affect workers. According to European Agency for Safety and Health at Work [3], stress results from a discrepancy between the demands and the pressures exerted on a person on the one hand, and the knowledge and abilities of that person, on the other hand. It challenges a person's ability to do his job. Stress arises not only in situations where job pressures exceed the employee's abilities, but also when the employee's knowledge and abilities are not used enough, and this causes a problem for him. In the work sphere, stress is defined by De Keyser et al. [4] as "a worker's response to the demands of the situation for which he doubts he has the necessary resources, and which he feels he has to face". According to the Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique [5], stress has emerged over the last fifteen years as one of the major risks that organizations and companies must face. In Europe, for example, 29% of employees complain of work-related stress [6]. Professional stress therefore appears to be one of the new risks that organizations will have to and are already facing. It affects several workers regardless of their socio-professional category [7]. In fact, stress has become one of the biggest problems at work within organizations, capable of jeopardizing the physical and mental health of the employee and affecting phenomena such as commitment, well-being, motivation, involvement, satisfaction, and dissatisfaction at work, etc.It therefore seems relevant to address this issue, which is more topical than ever, and to describe its impacts on job satisfaction. The main goal of our research is to identify the effect of a high level of stress on job satisfaction in a hospital workspace. Thus, the objective of the present study is to verify the existence of a probable link between stress at work and job satisfaction among doctors and nurses at the Sylvanus Olympio University Hospital Center (CHU-SO).Indeed, the phenomenon of stress in the workplace is a worrying reality in the world of work and nowadays it affects all modern industrial societies [8]. According to a report by the "Fédération des Intervenants en Risques Psychosociaux" [9], 24% of employees is in a state of hyper-stress, at an excessively high-level of stress and therefore at risk to their health. Furthermore, it should be noted that stress at work is often accentuated in African hospitals where several problems are encountered, including the lack of human and material resources [10]. In Togo, for example, a study which consisted in checking the level of stress among the health care staff (doctors, nurses, and midwives) of the three university hospitals, showed that 62.23% of respondents had an average level of stress and 37.77% had a high level of stress [11]. These data sufficiently show that health professionals are most of the time confronted with stressful situations. Indeed, health care workers, in the performance of their tasks, must collect, process, memorize and transmit sometimes complex, numerous and fluctuating information regarding the evolution of each patient's state of health [12].In addition, the situation of health care workers is still in question. Working conditions, staff shortages, and many other factors leading to strikes and protests, represent problems for health care workers. Health workers most often complain about the lack of work equipment (adequate technical platform) and the lack of resources (especially human resources) needed to provide quality care. According to the World Health organization [13], the norm is that one doctor is available for 10,000 inhabitants and one nurse for 4,000 inhabitants. However, according to "Ministere de la Santé du Togo" [14], In Togo there is one doctor for 14,410 inhabitants and one nurse for 4,814 inhabitants [15]. Despite this, the demands are increasing day by day, resulting in a high workload for the health care staff. We therefore note the presence of nursing staff who are dissatisfied with the working conditions in the health centres. The coronavirus pandemic has been raging in Togo since 2020. The pandemic increased the needs and workload in health centres. Consequently, health care staff are overloaded and exposed to high risks of contamination.The above these challenges and pressures can affect not only the performance of the health system and the level of job satisfaction of the staff. Indeed, the health care staff who are at the center of the system are under enormous and continuous pressure. These multiple pressures of different magnitudes, which mainly constitute psychosocial risk factors, can have consequences for workers in terms of aggression towards colleagues, patients, and carers. In addition, health care workers under pressure can provide poor reception, lack of empathy, errors in in the execution of tasks, diversion of patients' medicines and the trafficking of patients to private health structures [16].Trafficking patients to private health structures are signs of nonsatisfaction among workers in public health structures in Togo. This nonsatisfaction is also evidenced by the various strikes launched by SYNPHOT (National Union of Hospital Practitioners of Togo) in recent years. These various strikes are mostly motivated by lack of staff, dilapidated and outdated infrastructure, and equipment. The lack of adequate infrastructure and equipment put health care workers at risk and does not allow health care workers to provide quality care to their patients [17].The nursing staff of the CHU-SO is not spared from this alarming situation of stress in hospitals. We follow the behaviour of the doctors and nurses of this center over a period of three months. We have been able to observe that they complain about their work conditions, especially the material working conditions, as not being favourable to optimising performance. Similarly, they mention a lack of human resources given the tasks to be carried out. They overload themselves to satisfy as many patients as possible. In addition to all this, there are facts such as: the poor reception, the aggressiveness of the agents towards their colleagues, patients and companions, the lack of empathy, errors in the execution of tasks. Misappropriation and illicit sales of medicines and care materials were also observed on the part of the health care staff, leading to frequent sanctions from the executive managers. All these situations seem to lead to a lack of interest in the tasks on the part of some workers who consequently devote less time to it.To this end, the specialized literature presents interesting analyses. For example, the transactional model of Mackay et al. [18] integrates work relations, career development, internal work organization, and the role of the individual in the organization and the workload [19]. This model emphasizes the concept of balance between demands and available resources. Stress would result from the mismatch between the requirements of the work environment and the operator's ability to meet these requirements and/or the gap between individual's aspirations and professional reality.Thus, in a context marked by the presence of these facts and attitudes, it seems obvious to question the level of worker satisfaction. Locke et al. [20] defines job satisfaction as: "the pleasant or positive emotional state resulting from a person's evaluation of his or her work or work experiences". Spector et al. [21], meanwhile argues that job satisfaction is not only how people feel about their job as a whole, but also, how they feel about the different facets of the job. He explains that there are two approaches in the study of job satisfaction: the global approach and the facet approach. The global approach considers job satisfaction as a single general feeling towards work, while the facet approach focuses on the different factors of job satisfaction, such as salary and working environment.In this research, job satisfaction will refer specifically to the employee's feeling about their job. The Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy [22] conducted a study on health policies among 12,049 primary care doctors to measure their level of job satisfaction. The study led to the following results: dissatisfaction predominates among middle-aged general practitioners; a dissatisfaction rate that exceeds 30% in some countries. In France, the total prevalence of dissatisfied general practitioners reaches 33.8% (out of a sample of 500 doctors surveyed). It known that factors such as responsibilities, recognition, and the feeling of belonging to a group contribute to the increase in the level of worker satisfaction [23]. The two-factor theory [24] allows us to interpret job satisfaction in the sense that it distinguishes between the factors of satisfaction (intrinsic factors of motivation of the person at work through self-fulfilment, recognition, interest in the work, its content, responsibilities, opportunities for promotion and development) and factors of job dissatisfaction (factors extrinsic to the job such as personnel policy, company policy and management system, supervisory system, interpersonal relations between employees, working conditions and salary).The main question we address is whether stress at work influences the professional satisfaction of the health care staff (nurses and doctors) of the CHU-SO.To answer this question, we postulate that stress at work negatively influences the professional satisfaction of nurses and doctors at the CHU-SO. Based on this anticipated response, we make two specific hypotheses as follows:• doctors and nurses at the CHU-SO experience a high level of stress at work;• job satisfaction is low among CHU-SO doctors and nurses.We test all these hypotheses using the following methodological approach.

2. Methodology

- For this study, we visited the various departments of the CHU SO and we spoke to the doctors and nurses whom we met through the supervisors.For data collection, 200 agents were targeted out of a total of 291. However, we only considered the responses of 137 voluntary individuals (48 doctors and 89 nurses) because they fully completed the questionnaire forms. Thus, 55.5% of our study population are men and 44.5% are women. Of the 137 respondents, 21.2% are single, 73.7% are married, and 5.1% are widows and widowers. Regarding the kinship, 73% of respondents have dependent children, compared to 27% who have no children. We note in passing that participation in the survey was voluntary and anonymous.The survey questionnaire is designed based on research in the specialized literature and is divided into three (03) parts. The first part: it includes eight (08) items allowing to collect the socio-demographic information of the subject. The second part consists of the evaluation of the level of stress at work based on the 14-item Perceived Stress Scale of [25]. Finally, the third part is devoted to professional satisfaction, measured through the 5-item Professional Life Satisfaction Scale (ESVP) [26], and contextualized in Togo [27]. We have added two additional items which are: "I do a job that has a purpose and meaning for me"; and "Overall, I am satisfied with my job".Prior to the actual survey, we carried out a pre-test phase which consisted of administering the questionnaire to 22 randomly selected participants within the same university hospital. This phase allowed us to assess the level of understanding of the items by the study population. The analysis of the pre-survey data gave us a Cronbach's Alpha of 0.72 which is higher than our reference value of 0.50. This allows us to affirm that our questionnaire has a good internal consistency to carry out a broader effective administration of the questionnaire.In addition to the questionnaire, we also collected qualitative data that enabled us to enrich the analysis and interpretations of the results. We therefore conducted semi-directed interviews with three (03) people chosen at random according to their availability to participate in the interview (this is a doctor in paediatric surgery, a nurse in general medicine and a cardiology nurse).Data processing was carried out using SPSS 20.0 software. We analysed the data using the Pearson correlation test (crossing two variables and checking whether they are linked or not, the level of significance of the links and specify whether the correlation is positive or negative); and regressions (confirming the existence of a relationship between variables by reading the R and the R-two and seeing the part of a variable in the explanation of another variable). The processing of qualitative data was based on content analysis (logical-semantic technique) to identify the verbatims of the three interviewees. This led us to the following results.

3. Results

- The present study aims to highlight the link between stress at work and the professional satisfaction of doctors and nurses at the Sylvanus Olympio University Hospital Centre. The defined scoring grid of stress at work scale administrated is as follows:• Score < 25: no stress• Score between 25 and 49: average stress• Score > 50: pathological stressBased on this rating, we have drawn up the following staffing table:

|

|

|

|

4. Discussions

- Our results show that stress at work negatively impacts job satisfaction among doctors and nurses. Analysis based on correlations and regressions between the two variables showed that they are significantly related. Respondents are dissatisfied or satisfied depending on whether they are stressed or not. According to the data collected, most respondents are stressed, and this is mostly due to the deplorable working conditions explained above, the incessant pressures, and the work overload. Our empirical observations have also revealed distrust towards colleagues and the hierarchy, the harmful attitudes of some patients and companions, etc.Overall, our results corroborate those obtained by several authors. Indeed, “Le Fonds du Commonwealth” [30] conducted a study that consisted of measuring the level of job satisfaction among doctors. The analysis of the results based on the different characteristics linked to the organization of the health system and to medical practice shows that dissatisfaction is high among these doctors.[31], in their studies, found that the lack of technical and material resources contributes to the psychological burden of their work and increases exhaustion. In addition, the lack of resources leads to job dissatisfaction among palliative care doctors and nurses in the Center for palliative care and pain treatment in Paris (France).[32] showed that 65% of 105 nurses from the Beni Mellal Provincial Hospital Center were stressed by their work. According to the author, this level of stress is due to organizational factors such as poor working conditions, insufficient equipment to deal with emergencies, work overload, role ambiguity with poor distribution of tasks, insufficient autonomy in the work, lack of continuous training at the hospital level, the insufficiency of supervision, the tense social climate (conflicts between professionals and between nurses/users), and the poor support of the hierarchy.[33] showed that the main variables that are significant and positively associated with job satisfaction are relations with superiors, relations with colleagues, the possibility of organizing one's work satisfactorily, autonomy and responsibilities, communication and information within the organization, and personal development opportunities within the organization.[34] drew up a map of employees’ exposure to the main occupational risks in France. Indeed, exposure to risks and to the hardship of work has increased among employees, due to time constraints, work rhythms and contact with the public. Our data are consistent with the above published data.A study by [35] on doctors practicing in American rural areas showed that 25% od doctors planned to leave their profession in the next two years. In their study, 45% of doctors mentioned that the level of job dissatisfaction and work overload as the main reason a behind their plana to quit their jobs.In Norway, [36] showed with a representative sample of doctors that 28% of them considered the workload to be unacceptable. And 43% of them said that it was difficult for them to carry out their activity without being disturbed, while 19% found their work boring.Finally, a study carried out by [37] among Portuguese doctors revealed that a significant percentage of them wanted to change their profession due to the deterioration of working conditions, dissatisfaction in interprofessional relations, and the low income.

5. Conclusions

- In the hospital environment, the progress of science and medical research, as well as the appearance of new diagnostic and therapeutic means are real advances. However, few African countries follow this trend. Several health centres face various problems, making the activities of health care staff difficult [38]. To this end, workers are daily confronted with constraints and situations that are difficult to manage, plunging them into a state of stress at work.In Togo, this phenomenon is studied, both in public and private structures. In a context where stress is at a high level, we wondered about its possible repercussions on job satisfaction. This is what motivated this research, which aims to highlight the relationship between stress at work and job satisfaction.To conduct this research, we used the questionnaire survey technique with 137 voluntary individuals, which enabled us to collect quantitative data. In addition, we used the interview (with three participants) to obtain qualitative information and to deepen the information collected through the questionnaire. The SPSS software and the content analysis technique served as tools for processing and analysing the data collected. After the correlational and regression analyses, we found that doctors and nurses of the CHU-SO are dissatisfied because they are mainly stressed. In conclusion, there is a relationship between stress at work and job satisfaction. But this relationship is negative. This means that a high level of stress at work has a negative impact on job satisfaction among respondents. It would therefore be important to raise the awareness of company managers on the importance of implementing resources against stress at work. The creation of a friendly and comfortable work environment is conducive to physical and mental health of health care workers. In addition, the organization of socio-cultural activities and relaxation sessions for staff, the creation of games center within the structure and physical activities allow employees to relax in order to reduce the impact of psychological pressures. The implementation place of a listening and psychological support unit, etc. is also important to address employees concerns. Having frequently resources against stress despite the workload is sometimes necessary for employees to feel more fulfilled.Efforts have been made to conduct this research from a scientific point of view using a mixed methodology that combines the quantitative with the qualitative technics. This allowed us to make a more in-depth analysis of the results obtained. This combination of the two research methods strengthened our study because it is a factor that has raised the level of the scientific rigor. However, the research has some limitations. Indeed, the main limitation consists in the fact that the study population is made up of two socio-professional categories (doctors and nurses) who didn’t have the same training and who do not always share the same working realities (the tasks assigned for example are different from one category to another). This can pose a problem of homogeneity of the population and influence the quality of the results. However, the reality does not clearly relate these differences between the two socio-professional categories of respondents. Therefore, we believe that doctors and nurses can be included in the same group, especially when it comes to assessing job satisfaction related to stress in similar working conditions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML