-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2021; 11(3): 61-71

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20211103.01

Received: Sep. 14, 2021; Accepted: Oct. 13, 2021; Published: Oct. 30, 2021

Students’ Self-Efficacy and Challenges to Virtual Classes: A Conceptual Integrated Model of Rongo University-Kenya During COVID-19 Pandemic

Lazarus Millan Okello

Department of Educational Psychology and Science, Rongo University, Rongo, Kenya

Correspondence to: Lazarus Millan Okello, Department of Educational Psychology and Science, Rongo University, Rongo, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Nowadays, COVID-19 contributes a significant portion of the global burden of the killer diseases. Currently, the global spread of COVID-19 requires not only national-level responses but also active compliance with individual-level prevention measures outside and within the learning institutions. Self-efficacy in this context refers to individuals' confidence and certainty in their ability to successfully perform specific health-related behaviors in the COVID-19 containment. The aims of the study to investigate Students’ Self-Efficacy and Challenges to Virtual Classes: A Conceptual Integrated Model to University Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic. The results can guide the university policymakers to focus on increasing the awareness and knowledge of lecturers through conducting training programs on how to use the virtual system, because the lecturers have an important role in motivating the students to use the virtual system, which in turn affects the teaching performance and students’ self-efficiency. The universities need to focus on instilling the culture of virtual systems among students through training courses about the usefulness of virtual systems and develop their IT skills. The results of this study offer new insights and suggestions for decision makers to ensure the usage and adoption of virtual systems successfully during COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Students’ Self-Efficacy, Virtual Classes, Integrated Model, COVID-19

Cite this paper: Lazarus Millan Okello, Students’ Self-Efficacy and Challenges to Virtual Classes: A Conceptual Integrated Model of Rongo University-Kenya During COVID-19 Pandemic, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 11 No. 3, 2021, pp. 61-71. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20211103.01.

Article Outline

1. Research Questions

- 1. How do students engage in Virtual Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic?2. What are the challenges of virtual Learning among University Students during the COVID-19 period?

2. Research Methodology

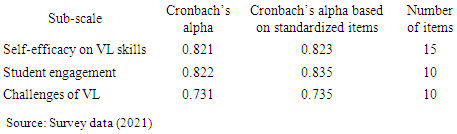

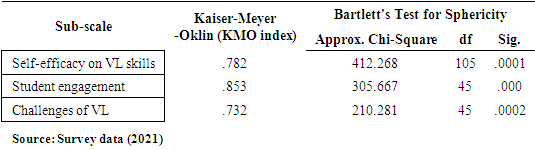

- This study adopted a descriptive cross-sectional design. The design is the most appropriate in a study where the independent variable cannot be directly manipulated since its manipulations have already occurred (Kerlinger, 2000). Convenience samples of 108 Rongo University students were recruited. The COVID-19 SSE questionnaire was administered to the sampled students. The target student populations of 150 third year education students were used. According to Krejcie and Morgan (1970), the sample size depends on the purpose of the study and the nature of the population under study. In order to determine the sample size of the students to be drawn from a population of 150, the study used Krejcie and Morgan (1970) table of determining sample size from a given population. For a population of seventy (150) a sample size of 108 participants were recommended. Simple random sampling was used to select 108 students included in the study. Purposive sampling was used to select the class representatives as per the specializations. The instrument included one set of questionnaire to students. The researcher used the responses to assess the students’ self-efficacy and challenges to virtual classes during COVID-19 Pandemic. To ensure content and face validity, the researcher piloted the instrument with 15 other students which were not included in the actual research. Cronbach’s Alpha of reliability co-efficient was used to determine internal consistency of the instrument. The instrument was considered sufficiently reliable at α≥0.7 as recommended by Mugenda and Mugenda (1999).

3. Introduction

- Virtual Learning Environments (VLE) can give learners access to educational resources, connect students with lecturers and facilitate distance lessons. The selection and the overall impact of VLE crucially depend on lecturers’ pedagogical and technological readiness and on students’ digital competences and hands on experience (accessibility of the internet and availability of appropriate ICT tools are preconditions to this). The choice of the teaching mode appropriately depends on the degree of uniformity and ICT investment a particular University intends to guarantee across different Faculties or schools. Various types of VLE exist, from basic content repositories, to scaffold curriculum-aligned repositories, to synchronous and asynchronous platforms offering a wide range of tools and services especially within the Library or ICT platforms set for both the staff and the students. Different models should be tested in different contexts and the selection should be based on an accurate analysis of the relative pros and cons of each VLE if the whole process is hoped to be successful.According to Shigemura et al., (2020); and WHO, (2019), in December 2019 a highly infectious disease, caused by a new coronavirus (the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2; SARS-CoV-2) was officially reported in Wuhan, China, and speedily spread outside China in the first months of 2020. The disease was called Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19) and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020 (WHO, 2020). In Kenya, COVID-19 was first reported on March 13, 2020 and schools were abruptly shut and they remained closed for several months, with learners in most learning levels forced to repeat their 2020 school year in 2021. This affected over 18 million children in Kenya including Universities and middle level colleges. The emergence of this virus has to a greater degree hindered Kenya’s Vision 2030 National Development Goals which try to achieve quality education for every child. COVID-19-related symptoms include high fever, cough, shortness of breath, and malaise, while in severe cases the infection may lead to severe pneumonia and cause death (Li et al., 2020).

4. Literature Review

- Students Engagement in Virtual Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic According to Koob, Schröpfer, Coenen, Kus and Schmidt (2021) under pandemic conditions academic institutions should focus on providing beneficial teaching formats and innovative ways to support students lacking social networks. Besides, they should consider developing means to help students structuring daily life as well as establishing initiatives to strengthen students’ self-efficacy beliefs. Hills and Eraso (2021) outlined that contrary to a perceived sense of people’s adherence to SD, the vast majority of participants did not adhere to all SD rules and nearly half intentionally did not adhere. Given the lack of approved vaccines for COVID-19, at the time of the study, and the threat of a second wave of cases, it is essential to understand the true extent of no adherence and the factors which predict it, so that policy and interventions can limit the threat. Valverde-Berrocoso, Garrido-Arroyo, Burgos-Videla and Morales-Cevallos (2020) from their analysis of the content of the selected articles, three main nodes are identified: (a) e-learning and online students; (b) e-learning and online teachers; and (c) e-learning and curriculum. The e-learning and online student’s node includes two main themes: self-regulation and dropout and retention. The node e-learning and curriculum revealed impact and success as the main research subtopic. As a condition for the success of online education, the scholars noted the fundamental need to promote an educational research line that develops efficient pedagogical designs that facilitate the learning of competencies.In a study done by Ali (2020) in view of online and remote learning in higher education institutes: COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing requirement presented undue challenges on all stakeholders to go online as they have to work in a time constraint and resource restraint situation. The study argued that adopting online learning environment isn’t just a technical issue. It is a pedagogical and instructional challenge. As such, ample preparation in regards to teaching materials and curriculum and assessment knowledge is vital in online education. according to Amodan, Bulage, Katana, Ario, Fodjo, Colebunders and Wanyenze (2020), the low levels of adherence revealed could imply that the compliance to the government preventive measures could have potentially further declined during the course of the outbreak, reflecting the need to upscale risk communication strategies in the COVID-19 response and future similar outbreaks. Dhawan (2020) agreed that teachers have become habitual to traditional methods of teaching in the form of face-to-face lectures, and therefore, they hesitate in accepting any change. But amidst this crisis, we have no other alternative left other than adapting to the dynamic situation and accepting the change. The researcher acknowledged however, that a number of students are less affluent and belong to less tech-savvy families with financial resources restrictions; therefore, they may lose out when classes occur online. They may lose out because of the heavy costs associated with digital devices and internet data plans. This digital divide may therefore widen the gaps of inequality. The study advised the need to have proper clarity on the purpose and context of technology adoption. E-learning can help in providing inclusive education even at the time of crisis.Jiang, Islam, Gu, and Spector (2021) underscored an urgent need to measure learner satisfaction with using online learning platforms as millions of Chinese university students now rely on them to continue their studies due to the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Jiang, Islam, Gu, and Spector, University students should gradually strengthen their basic computer competence in different ways so as to enhance their computer self-efficacy. Governments, universities and service providers can also hold lectures online to help university students improve computer capabilities. More importantly, students should also be encouraged to take the initiative in learning how to use platforms for deep online learning and learning management. In regard to regional differences, the study outlined that governments, universities and service providers can improve the quality of online learning platforms by taking into account the characteristics of student groups in different regions.According to Zalat and Bolbol (2021) e-learning was underutilized in the past, especially in developing countries. However, the current crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic enforced the entire world to rely on it for education. In their study, majority of participants strongly agreed with the perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and acceptance of e-learning. The highest challenge for accepting e-learning were insufficient/ unstable internet connectivity, inadequate computer labs, lack of computers/ laptops, and technical problems. Mahyoob (2020) earlier noted that the main problems that influence and impact online EFL learning during COVID-19 are related to technical, academic, and communication challenges. The scholar postulated that most EFL learners are not satisfied with continuing online learning, as they could not fulfill the expected progress in language learning performance. Some learners faced internet connectivity problems, accessing classes, and downloading courses’ materials problems. Further, online exams could not be opened on learners’ mobile phones. Regarding language communication issues, learners could not effectively interact with teachers during virtual classes of English language skills, as revealed in learners’ responses to open-ended questions.Zarzycka, Krasodomska, Anna and Jin (2020) underscored the fact that the rapid development of technology impacts not only people’s lives in general, but also education (Concannon et al., 2005). The study commended COVID-19 lockdown; and that distance methods of learning are irreplaceable when it comes to supporting the educational process. Their implementation and use can also have other positive consequences, such as the improvement in students’ competence in terms of soft skills, including communication and collaboration capabilities. Oraif and Elyas (2021) revealed a high level of engagement among EFL Saudi learners. This helped to generate recommendations to improve EFL practices, primarily through the use of an online environment either at the national level in the Saudi context or the international level. Tanius, Alwani, and Muein (2020) however, argued that online learning technology experience, learners' attitudes, learners' motivation, computer anxiety, and social support correlate with self-efficacy on online learning technology. Furthermore, the finding revealed that male and female respondents and different ages have similar opinions on the factors that contribute to online learning technology. Challenges of Virtual Learning among University Students during COVID-19 Pandemic The research of Pokhrel and Chhetri (2021) on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning across the world concludes that although various studies have been carried out, in the case of developing countries, suitable pedagogy and platform for different class levels of higher secondary, middle and primary education need to be explored further. Internet bandwidth is relatively low with lesser access points, and data packages are costly in comparison to the income of the people in many developing countries, thus making accessibility and affordability inadequate. Policy-level intervention is required to improve this situation. Sarkar, Das, Rahman and Zobaer (2021) have suggested that online class is still the only medium to continue education in the middle of this pandemic situation when the government has imposed school closure, and countrywide lockdown started. The study however, acknowledged that rural areas face issues with electricity connection which is an additional burden. Moreover, students often do not have electronic gadgets to participate in online classes effectively. Nonetheless, the study revealed that female students had more positive attitudes toward virtual classes than male students.Cedric and Mpungose (2020) on their study on emergent transition from face-to-face to online learning in a South African University in the context of the Coronavirus pandemic suggested that despite challenges experienced by students in transitioning from face-to-face to e-learning-in particular, the prominence of the digital divide as the main hindrance to students realizing effective e-learning-overall, the customization of the Moodle LMS to meet the local needs of disadvantaged students is beneficial to realize e-learning. Moreover, the findings indicate that while there may be many challenges that can hinder students from realizing the full potential of e-learning, alternative pathways like the provision of free data bandwidth, free physical resources and online resources, and the use of an information Centre for blended learning and others, seem to be the solution in the context of COVID-19. Al-Rasheed (2021) also revealed eight main challenges facing undergraduate women during the pandemic outbreak. Some challenges were associated with online learning in the literature, but their impact increased with the full transition and quarantine, namely, technical issues, limited availability of digital devices, distractions and time management, stress and psychological pressure, and lack of in-person interaction. According to Maatuk, Elberkawi, Aljawarneh, and Alharbi (2021) the main obstacle to e-learning is the low-quality of Internet services in Libya during the pandemic period. Faculty members agree that e-learning is useful in increasing students’ computer skills, although it requires significant financial resources. The university has to provide internet service to students and teaching staff members with enough computer devices to apply e-learning. A modern electronic library and dedicated classrooms with all types of equipment and tools needed are also necessary to apply e-learning. Alsoud and Harasis (2021) also suggested that while a significant proportion of students use digital learning tools, many of them face immense online learning challenges such as Internet connectivity issues, dedicated space for studying, personal device for attending the online classes, and the feel of anxieties. Therefore, the government of Jordan, policymakers, and universities should invest to develop a resilient education system that supports electronic and distance learning for the future of Jordan’s educational system. A survey developed by Alhubaishy (2020) on Factors Influencing Computing Students’ Readiness to Online Learning for Understanding Software Engineering Foundations in Saudi Arabia showed that students’ readiness level for online learning is within the acceptable range while some improvements are needed. Furthermore, the study found that students’ cognition, willingness, ignorance, and the amount of assistant and help they receive play a significant role in the success/failure of the adoption of learning SE foundations through online environment. Amodan, Bulage, Katana, Ario, Fodjo, Colebunders and Wanyenze (2020) did a research on the Level and Determinants of Adherence to COVID-19 Preventive Measures in the First Stage of the Outbreak in Uganda. The low levels of adherence revealed in this study could imply that the compliance to the government preventive measures could have potentially further declined during the course of the outbreak, reflecting the need to upscale risk communication strategies in the COVID-19 response and future similar outbreaks. Additionally, enforcement of preventive measures, such as wearing masks, hand hygiene, and physical distancing, in the population, could stabilize the outbreak and halt the viral transmission. Behaviour change programs need to be intensified to improve the level of adherence and satisfaction with preventative measures, especially the use of masks. Special messages and efforts should target men, large families, and people living outside Kampala city center and be popularized at the community level by health workers and community leaders.Almaiah1, Al-Khasawneh and Althunibat (2020) explored the critical challenges and factors influencing the E-learning system usage during COVID-19 pandemic. Based on the results, the respondents stated that the critical factors that affect the usage of e-learning system and should universities take them into the future plans were: (1) technological factors, (2) e-learning system quality factors, (3) cultural aspects, (4) self-efficacy factors and (5) trust factors. In addition, the results indicated that there are three main challenges that impede the usage of e-learning system, namely, (1) change management issues, (2) e-learning system technical issues and (3) financial support issues. Nzaji, Mwamba, Miema, Umba, Kangulu, Ndala, Mukendi, Mutombo, Kabasu, Katala, Mbala, and Numbi (2021) have argued that not been regularly informed about the pandemic and bad knowledge about COVID-19 are factors of non-adherence to public health instructions. The non-adherence to these public health instructions can increase risk for the transmission of the pandemic. The scholars concluded that change in declared willingness to comply with public health measures in the pandemic concern is necessary for the successful response and containment of the disease. Daas, Hubbard, Johnston, and Dixon (2021) in their study revealed that COVID-19 has unprecedented consequences on population health, with governments worldwide issuing stringent public health directives. In the absence of a vaccine, a key way to control the pandemic is through behavioral change: people adhering to transmission reducing behaviors (TRBs), such as physical distancing, hand washing and wearing face covering. Ditekemena, Nkamba, Muhindo, Siewe, Luhata, Van den Bergh, Kitoto, Damme, Muyembe, and Colebunders (2020) also noted that despite compulsory restrictions imposed by the government, only about half of the respondents adhered to COVID-19 preventive measures in the DRC. Further, the study found an overall non adherence to preventive measures of 60.3% among adults in the DRC. COVID-19 preventive behaviour varied between the provinces. Physical distancing, which has demonstrated its efficacy in reducing viral transmission, was well observed only in Kinshasa, North Kivu and Kasai-Central, with non-adherence rates of 20%, 12% and 40%, respectively. On the other hand, Hayat, Keshavarzi, Zare, Bazrafcan, Rezaee, Faghihi, Amini and Kojuri (2021) disclosed three main categories of responses: factors that were effective in aiding the development of medical e-learning, opportunities and challenges, and the evaluation of e-learning. They noted that before course contents can be virtualized, it should first be determined how much content can be virtualized successfully. Also, creating web groups to discuss educational topics can provide more opportunities for students to participate and engage. Creating and developing the necessary infrastructure for quality education, including providing and supporting desirable educational software, increasing and improving the speed of the Internet, granting free Internet packages to professors and students can improve virtual education.Nikou (2021) extensively did an analysis of students’ perspectives on e-learning participation - the case of COVID-19 pandemic. The study revealed that the students’ intention to participate in e-learning is significantly affected by the COVID-19 awareness and perceived challenges of the pandemic. According to the study, this may be because of the subjective nature of the studied phenomena, which relies on the factors that relate to the individual (i.e. awareness and perceived challenges of the pandemic). König, Daniela, Jäger-Biela and Glutsch (2020) also suggested from the findings of regression analyses that information and communication technologies (ICT) tools, particularly digital teacher competence and teacher education opportunities to learn digital competence, are instrumental in adapting to online teaching during COVID-19 school closures. Kim and Kim (2020) did a study on the Impact of Health Beliefs and Resource Factors on Preventive Behaviours against the COVID-19 Pandemic. The study noted that First, not all preventive behaviors appear to be similar; wearing a mask is the most frequent preventive behaviour. Second, a simple means analysis showed that women engage in recommended behaviour more frequently than men do. This result is believed to be because women are more sensitive to risk. Third, the results of the regression analysis show that gender (female), age, the number of elderly people in one’s family, perceived severity, perceived benefit, self-efficacy, good family health, media exposure, knowledge, personal health status, and social support positively affect preventive actions. Suggestively, Maheshwari (2021) argued that with the increased use of smart phones with the current generation, to increase the perceived enjoyment of the students with the online learning, the lecturers might be encouraged to use videos, audios and instant messaging to contact and provide the feedback to the students. The study added that it is important for universities to prepare for any such future crisis. The study further noted that the support provided from the institution in the form of class activities, class interaction and teachers’ support played an important role in students’ decision-making to study the courses online in the future.

5. Results, Findings and Discussions of the Study

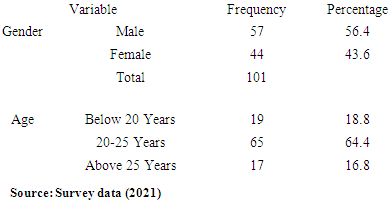

- Return Rate and Demographic InformationThe study sought to explore the demographic information of the respondents. The demographic information investigated includes the students’ gender and age. This information was considered important for the purpose of generalization of the results of the survey. Table 1 shows the demographics of the respondents of the study.

|

|

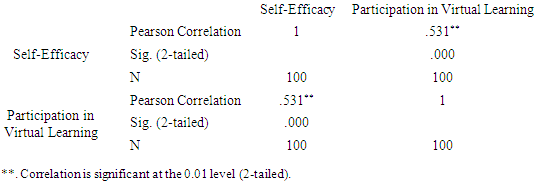

|

|

|

|

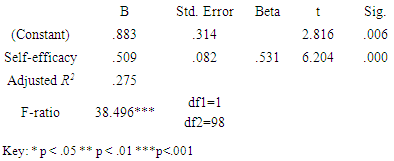

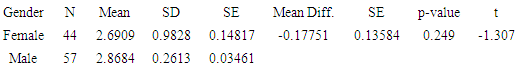

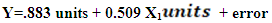

From the model, for each one unit increase in the level of self-efficacy of skills, there is a resultant rise in the level students’ participation in Virtual learning by 0.509 units. In general, the model was adequate enough to predict the level of students’ participation in Virtual learning among the university students. The model was statistically significant F (1, 98) = 38.496, p <.001, Adjusted R2 =.275. Students Demographic Characteristics and Participation in Virtual Learning Students’ Gender on Participation in Virtual LearningAn independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the students’ participation in Virtual learning scores for males and females. The analysis helped to establish whether there is a significant difference in the mean participation in virtual learning scores for males and females. Gender, being independent variable was categorical (males/females) and participation in virtual learning scores, being dependent variable, was continuous variable t-test was the appropriate. Using Levene’s test, assumption of equal variance was not violated (p>.05) as required for an independent t-test. Table 7 shows the summary of an Independent sample t-test results.

From the model, for each one unit increase in the level of self-efficacy of skills, there is a resultant rise in the level students’ participation in Virtual learning by 0.509 units. In general, the model was adequate enough to predict the level of students’ participation in Virtual learning among the university students. The model was statistically significant F (1, 98) = 38.496, p <.001, Adjusted R2 =.275. Students Demographic Characteristics and Participation in Virtual Learning Students’ Gender on Participation in Virtual LearningAn independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the students’ participation in Virtual learning scores for males and females. The analysis helped to establish whether there is a significant difference in the mean participation in virtual learning scores for males and females. Gender, being independent variable was categorical (males/females) and participation in virtual learning scores, being dependent variable, was continuous variable t-test was the appropriate. Using Levene’s test, assumption of equal variance was not violated (p>.05) as required for an independent t-test. Table 7 shows the summary of an Independent sample t-test results.

|

|

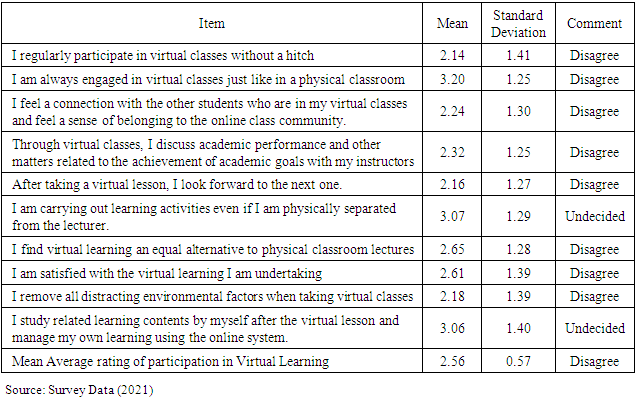

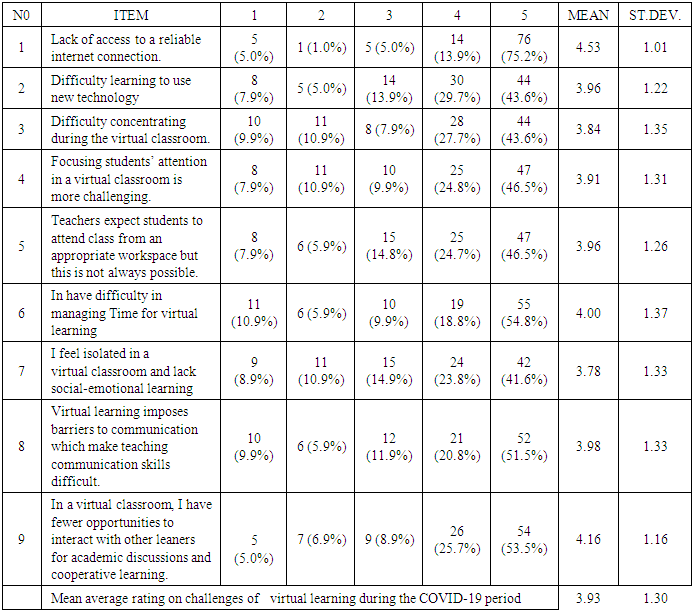

6. Challenges of Virtual Learning among Rongo University Students during COVID-19 Pandemic

- The third objective of the study sought to investigate the challenges of virtual learning during the COVID-19 period among Rongo University students. The sampled students were provided with Likert scaled itemed questionnaire whose items were possible challenges faced in virtual learning. Using the rating scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) the sampled students rated the items based the level agreement by the respondents. Their responses were presented in frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations as summarized in Appendix 2.

7. Findings on the Challenges of Virtual Learning

- The results of the survey have revealed that students from Rongo University face overwhelming challenges towards virtual learning during the COVID-19 period. In the scale of 1 to 5, the students’ rating of challenges they face in their bid to enjoy virtual learning received overall average rating of 3.93 with a standard deviation of 1.30. Some of the challenges are established to be insurmountable in the short period. For example, access to internet was established to be a very common challenge to most of the students in Rongo University, as reflected by mean challenge rating of 4.53 (SD=1.01). Over three quarters 76 (75.2%) of the sampled students from the University strongly agreed that lack of access to a reliable internet connection is a major challenge to virtual learning during the COVID-19 period. Only 6 (6.0%) of the respondents either disagreed or strongly disagreed that internet connection is a challenge to them. This suggests that internet connection is either unstable or totally not accessible to most of the students in their bid to learn virtually. Besides access, the findings of the study has established that technological knowhow also present a fairly strong (M=3.96; SD=1.22) challenge to some of the students. For example, 30 (29.7%) and 44 (43.6%) of the surveyed students from Rongo University agreed and strongly agreed, respectively, that they face difficulty in learning to use new technology. Only 13 (12.9%) of the respondents alluded that they do not have any difficulty in learning to use the new technology, but some 14 (13.9%) of them remained non-committal on the matter. This implies that many of the students in Rongo University do not have appropriate technical skills to use online learning platforms effectively, which is a hindrance to virtual learning during COVID=19 scourge. Similarly, the results of the survey also point out that students face difficulty in concentrating in the virtual classroom. This was reflected by a mean rating of 3.84 (SD=1.35), with 28 (27.7%) of the students agreeing and 44 (43.6%) others strongly agreeing that they always have difficulty in concentrating during their virtual classroom learning. Only 21 (20.8%) of the surveyed students claimed that they have no difficulty in concentrating during the virtual classroom learning. Lack of concentration is occasioned by no stringent measures for student behavior management unlike in physical classroom setup where the lecturers set rules and routines. Besides, in a virtual classroom, some students logging in from homes with non-conducive learning environment which make concentration and online learning more challenging. In some homes, students face numerous interruptions including family matters. In fact, 72 (71.3%) of the surveyed students from Rongo University either agreed or strongly agreed that focusing students’ attention in a virtual classroom is more challenging. This challenge of difficulty to focus was rated at 3.91 with a standard deviation of 1.31, suggesting that many students find it hard to fully focus in their studies without a lecturer’s physical presence and face-to-face contact.Another challenge that was unearthed by the study is lack of appropriate workplace for using virtual learning equipment by majority of the students who study at Rongo University, as indicated by a mean rating of 3.96 with a standard deviation of 1.26. Close to a half 47 (46.5%) of the sampled students strongly agreed and another 25 (24.7%) of them agreed that although their lecturers expect them to attend virtual class lessons from an appropriate workspace, this is not always possible in their cases. This means that many of the students in the University lack suitable desks or tables at home to sit for virtual lessons.Equally, the results of the survey established a rating in difficulty in time management by students during virtual learning of 4.00 in the scale of 1to 5, with a standard deviation of 1.37. This was corroborated by a significant majority 74 (73.6%) of students respondents who confirmed that they have difficulty in managing their time for virtual learning. Although, students are expected to be committed to their studies, learn how to manage time and set their daily schedules, constant distractions and interferences pose a big challenge to time management with regard to virtual classroom learning. Only 17 (16.8%) of the students who participated in the survey alluded that they have no difficulty in managing their time during virtual learning. Additionally, the study found out that the use of virtual learning has come along with the challenge of isolation. For instance, out of the 101 students who were surveyed, 66 of them translating to 65.4% of the respondents were in agreement that they feel isolated in a virtual classroom hence they lack social-emotional learning. Student isolation, as a challenge to virtual learning, was rated at 3.78 (SD=1.33), with only less than a fifth 20 (19.8%) of the sampled students insisting that they do not feel isolated in a virtual classroom. Coupled with the possibility of students feeling isolated during virtual learning, lack of opportunity for contact between the lecturers and the students and even among the students themselves pose another challenge to virtual learning during COVID-19 scourge. In the scale of 1 to 5, lack of opportunities to intermingle among the students was deviation of 1.16. Whilst, only 12 (11.9%) of the respondents purported that they never feel isolated during virtual learning, nearly four out of every five 80 (79.2%) of the students who took part in the survey agreed that in a virtual classroom, they have fewer opportunities to interact with other students for academic discussions and cooperative learning. This indicates that during the virtual learning, many students hardly get fully engaged without a teacher’s physical presence and face-to-face contact. Virtual learning causes lack of physical communication among the students and lecturers, this was revealed by 21 (20.8%) and 52 (51.5%) of the surveyed students who agreed and strongly agreed, respectively, that virtual learning imposes barriers to communication which make learning communication skills difficult. This challenge was rated at 3.98 (SD=1.33), suggesting that most of the students confirmed that they have fewer opportunities to physically interrelate with the lecturers and other students in a virtual classroom. This means they have fewer opportunities for academic discussions and cooperative learning or even informal interactions, which forms key aspect of overall growth of students.

|

8. Conclusions

- The first objective of the study sought to establish the level of students’ participation and engagement in Virtual Learning during COVID-19. The results of the study revealed that there was generally low level of participation of students in Virtual Learning among Rongo University students, regardless of the fact that COVID-19 pandemic has affected physical learning. It was therefore concluded that the students need to gradually strengthen their basic computer competency so that their skills could be enhanced. They can do this by taking initiative in learning how to use varied platforms for virtual learning and management. Lecturers could equally play the role of motivating the students to develop their own self confidence and think positively about the virtual learning mode. The Universities could therefore focus on providing strong and reliable virtual connectivity and innovative ways to support students lacking individual networks. The second objective of the study sought to investigate the challenges of virtual learning during the COVID-19 period among Rongo University students. The results of the survey have revealed that students from Rongo University face overwhelming challenges towards virtual learning during the COVID-19 period. The study noted that internet bandwidth was relatively low with lesser access points at the campus and data packages were costly in comparison to the learners’ income making accessibility and affordability to be inadequate. There is need for the University to provide free data, free physical resources and online resources and also consider using blended learning approach if solution in the context of COVID-19 is to be found. The management should consider developing infrastructure for quality including provisions for desirable and affordable software for the learners and teaching staffs, improving the internet speed, providing free internet packages to the lecturers and students and also providing several learning points connected to internet to improve virtual learning in the University.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML