Qi Wang

Department of Human Development, Cornell University, MVR Hall, Ithaca, NY, USA

Correspondence to: Qi Wang, Department of Human Development, Cornell University, MVR Hall, Ithaca, NY, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

I describe in this article the creation of the Purposes of Online Memory Sharing Scale (POMSS). I provide an overview of the theoretical and empirical backgrounds against which the scale was developed. I then present data from a pilot sample that indicate that the scale as a whole is a reliable measure of the reasons for which people share their experiences online. In addition, three of the subscales - Self, Social, and Therapeutic – showed acceptable to excellent internal consistency reliability in the pilot sample, whereas the Directive subscale had poor internal consistency and should be used with caution. The various purposes of online memory sharing positively predicted the frequency of memory-sharing activities, which lends support for the validity of the scale. The Purposes of Online Memory Sharing Scale (POMSS) provides a useful tool for researchers to examine memory expression and communication in the digital age.

Keywords:

Memory sharing, Social media, Internet, Memory functions, Measurement, Scale, Reliability, Validity

Cite this paper: Qi Wang, Creation of the Purposes of Online Memory Sharing Scale, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 10 No. 3, 2020, pp. 65-70. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20201003.01.

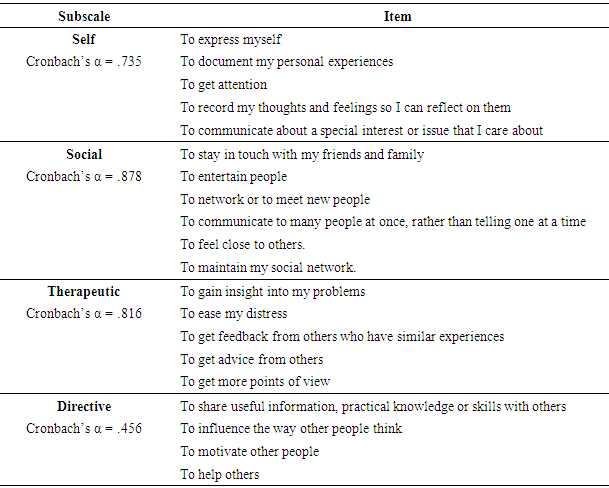

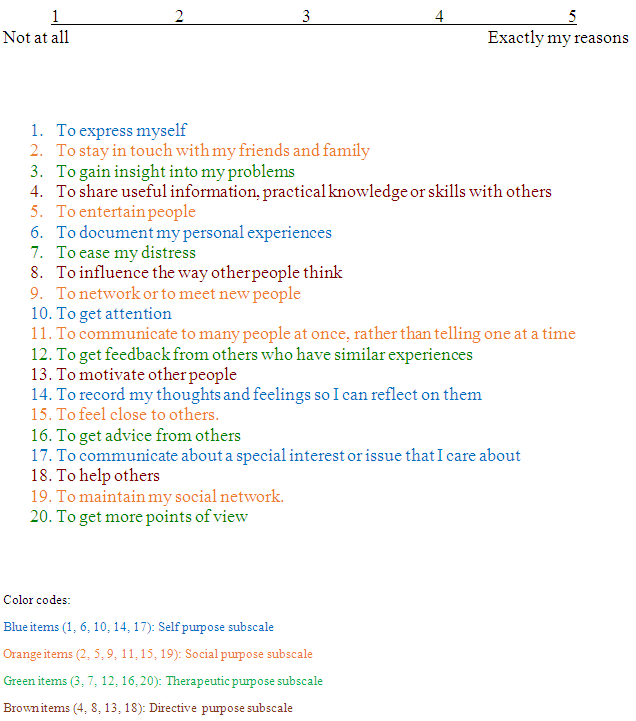

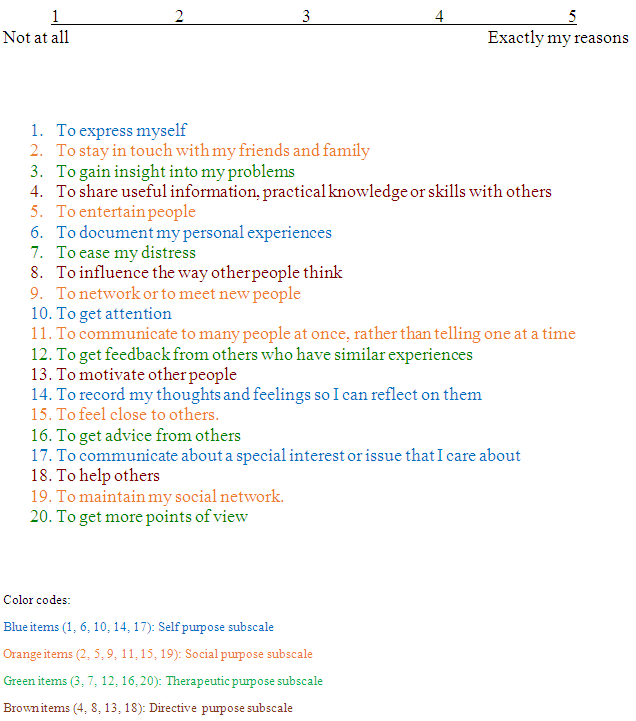

Memory sharing is a common everyday activity. We share memories with others to convey information about who we are. We share memories to entertain others and to develop and maintain relationship closeness. We also share memories of negative experiences to gain sympathy and support and to solicit advice from others. We further share memories to impart lessons we have learned from the past and to help others. These purposes of memory sharing for self, social, therapeutic, and directive functions have been documented in extensive empirical research (e.g., Alea & Bluck, 2003; Alea & Wang, 2015; Bluck, 2003; Kulkofsky, Wang, & Hou, 2010; Pillemer, 1998; Wang, Koh, Song, & Hou, 2015). Importantly, in the contemporary digitally mediated society, sharing memory is no longer limited to face-to-face interactions but frequently takes place online, via social media. Does online memory sharing serve similar purposes as memory sharing in person? Based on data from a large survey by the Pew Internet and American Life Project with a nationally representative sample of bloggers (Lenhart & Fox, 2006), Wang (2013) suggests that the major reasons provided by the respondents for their sharing personal experiences online can be sorted into three broad functions: Self (e.g., to express and document the self and to store self-relevant information), Social (e.g., to share personal experiences with others, to connect with family and friends, to entertain others, and social networking), and Directive (e.g., to guide and influence thoughts, actions and activities of others). This observation is confirmed by findings from communication research on motives for personal blogging (Hollenbaugh, 2011; Lee, Im, & Taylor, 2008; Schmitt, Dayanim, & Matthias, 2008). In addition to the three functions, the extant research further suggests that sharing memories online is also used for the therapeutic purpose of emotion regulation and coping (Baker & Moore, 2011; Nardi, Schiano, & Gumbrecht, 2004). Thus, online memory sharing appears to serve similar purposes as memory sharing in person. Several scales have been developed to measure the reasons for online personal blogging or macroblogging (e.g., Baker & Moore, 2011; Hollenbaugh, 2011). However, these scales may not be pertinent to online memory sharing more generally, especially memory sharing via microblogging such as status updates, which has become a more prominent form of online communication particularly among teens and young adults (Lenhart, Purcell, Smith, & Zichuhr, 2010). To better understand the reasons for which people share their experiences online regardless of the social media outlet, I developed a 20-item Purposes of Online Memory Sharing Scale (POMSS). The scale was constructed in reference to prior research on motives for personal blogging (Baker & Moore, 2011; Hollenbaugh, 2011; Lee et al., 2008; Lenhart & Fox, 2006) as well as the memory function literature (Alea & Bluck, 2003; Bluck, 2003; Kulkofsky et al., 2010; Pillemer, 1998; Wang et al., 2015). It consists of four subscales - Self, Social, Therapeutic, and Directive, which include 5 items, 6 items, 5 items, and 4 items, respectively. The Social purpose subscale contains more items than do other subscales given the prominent social functions of sharing memories with others (Alea & Bluck, 2003; Guan & Wang, 2020; Kulkofsky et al., 2010). It is important to note that different from the directive functions of private memory recall that focus on using the past for one’s own current and future problem solving (Pillermer, 1998), directive functions in the context of memory sharing focus on using the past to help others (e.g., to motivate other people to action). Self-help related functions of memory sharing (e.g., to seek advice or social support) are captured by the Therapeutic subscale. The POMSS is provided in Appendix A. The subscales and their items are listed in Table 1. Table 1. Purposes of Online Memory Sharing Scale (POMSS)

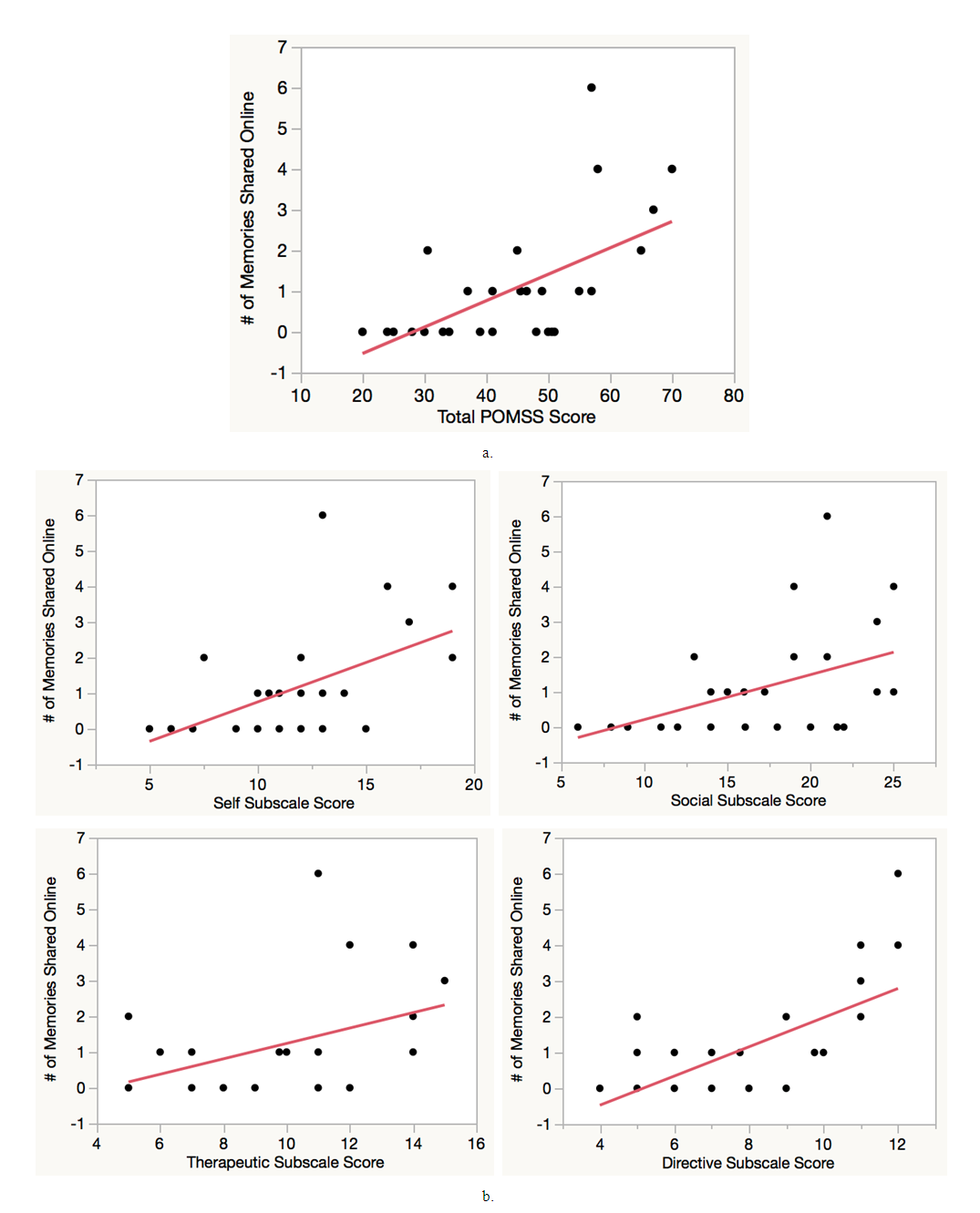

|

| |

|

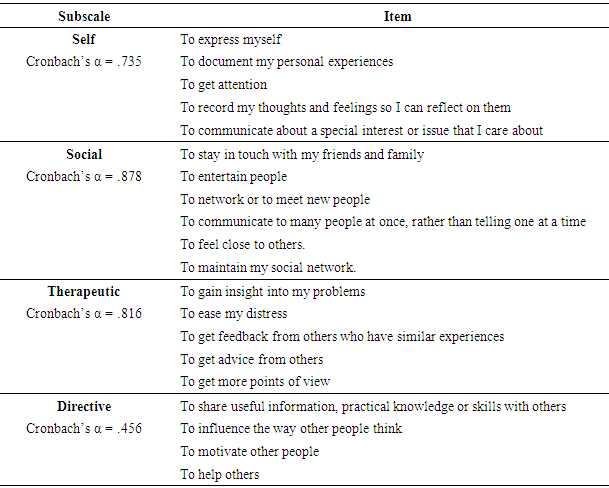

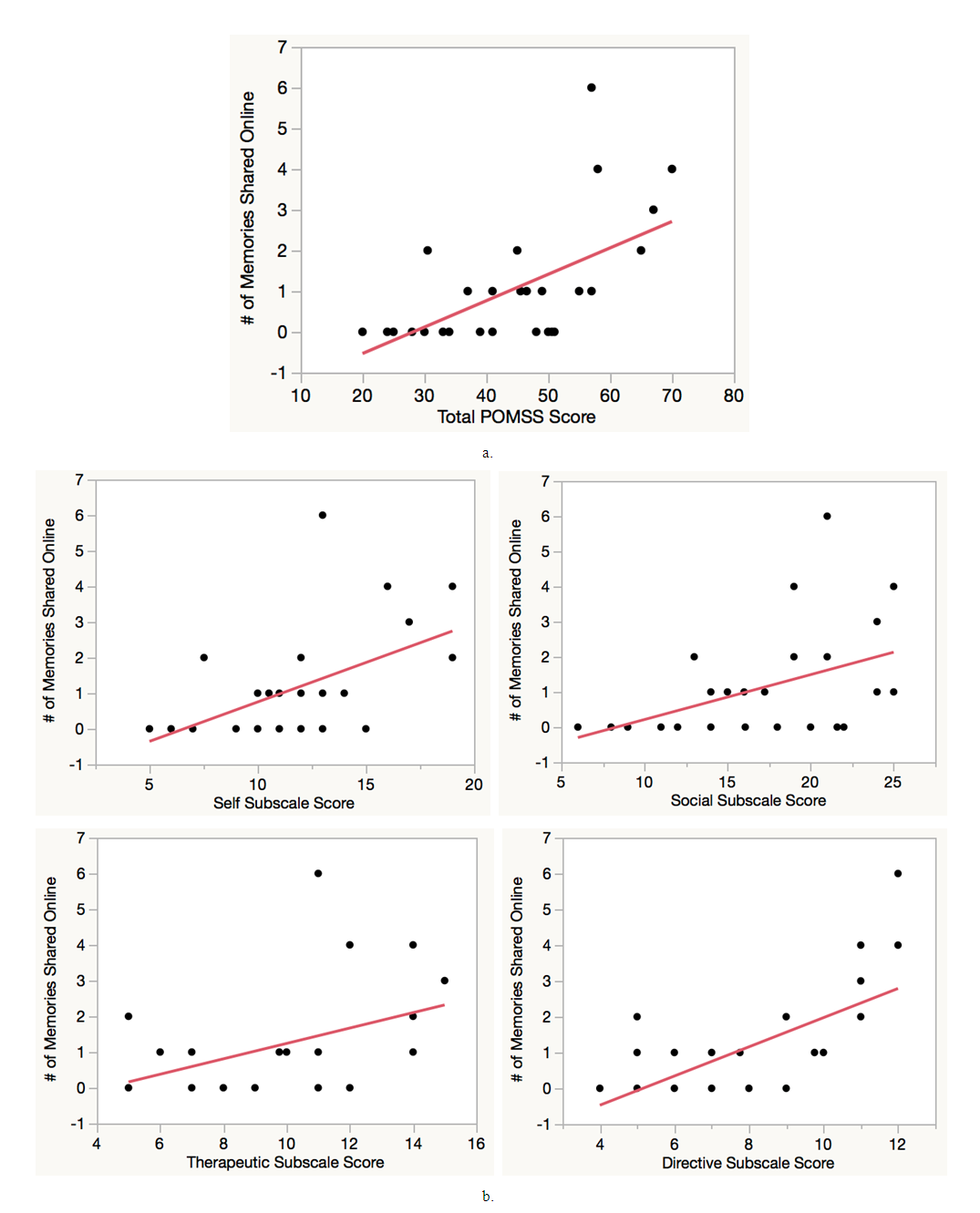

The POMSS was pilot-tested with 31 college students (Mean Age = 20.76 years, SD = .92), including 24 females and 7 males, as part of a larger study that investigated the effect of online memory sharing on memory retention (Wang, Lee, & Hou, 2017). Participants were asked to indicate how much each item described their reasons for sharing personal experiences online by choosing a response from 1 (‘‘not at all’’) to 5 (‘‘exactly my reasons’’). Participants also kept a daily diary for a week in which they recorded all the events that happened to them on each day and reported whether they shared any of the events online. The total number of memories participants shared online over the week was tallied. A few missing data were substituted with group means. Reliability analysis showed excellent internal consistency of the scale as a whole, with Cronbach’s α = .926. Cronbach’s α when each item was excluded ranged from .917 to .929, indicating excellent internal consistency across items. Further reliability analysis was conducted for each subscale (see Table 1). The internal consistency reliability ranged from being acceptable to excellent for the first three subscales but was poor for the fourth subscale: Cronbach’s α = .735 for Self subscale; Cronbach’s α = .878 for Social subscale; Cronbach’s α = .816 for Therapeutic subscale; Cronbach’s α = .456 for Directive subscale. One explanation for the poor reliability of the Directive subscale is that there are only 4 items for this subscale, each likely capturing one unique aspect of directive functions of memory sharing. To include additional items in the subscale, or to make the items focus on one aspect of directive functions (e.g., to impart lessons for current and future behavioral guidance) may increase the internal consistency of the subscale. Alternatively, the four items in the current subscale can be considered separately to understand why people share memories online for various directive functions. In addition, the small sample size in the pilot test might also have contributed to the low internal consistency of the subscale.Regression analyses were further conducted with the participants’ total POMSS score as well as the subscale scores, respectively, predicting the total number of memories participants shared online over a one-week period (See Figure 1). The various purposes of online memory sharing positively predicted the frequency of memory-sharing activities: total POMSS score, t = 4.05, B = .065, p = .0003; the Self subscale score, t = 3.77, B = .22, p = .0007; the Social subscale score, t = 3.10, B = .13, p = .0043; the Therapeutic subscale score, t = 2.90, B = .22, p = .007; and the Directive subscale score, t = 4.85, B = .41, p < .0001. Thus, the more the participants endorsed the purposes of online memory sharing, the more frequently they shared personal memories online.  | Figure 1. The number of memories shared online as a function of a) the total POMSS score and b) the four subscale scores |

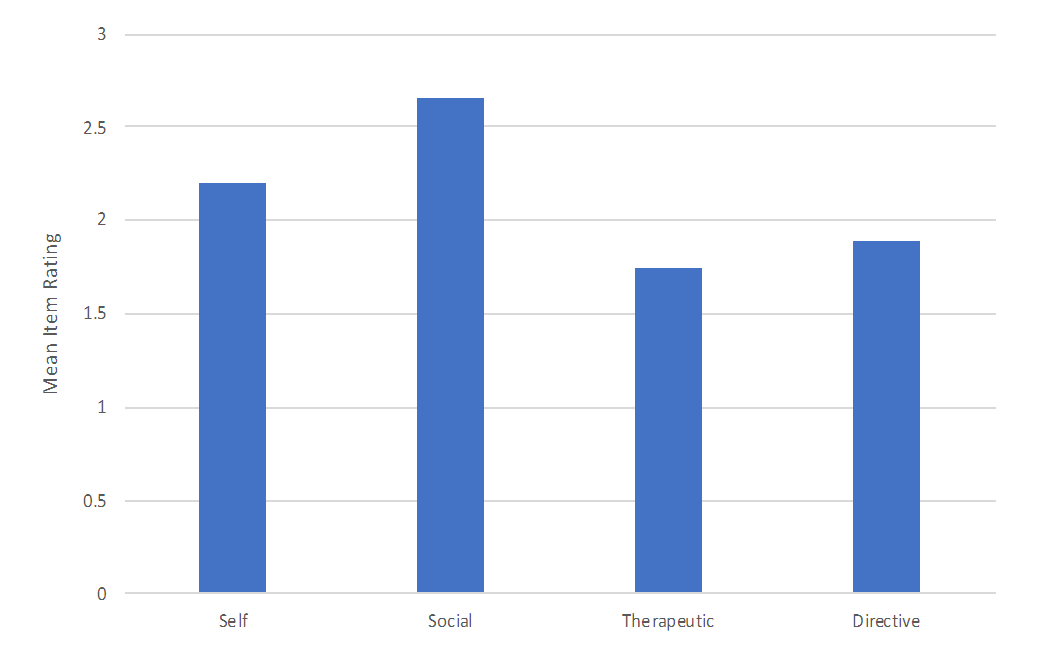

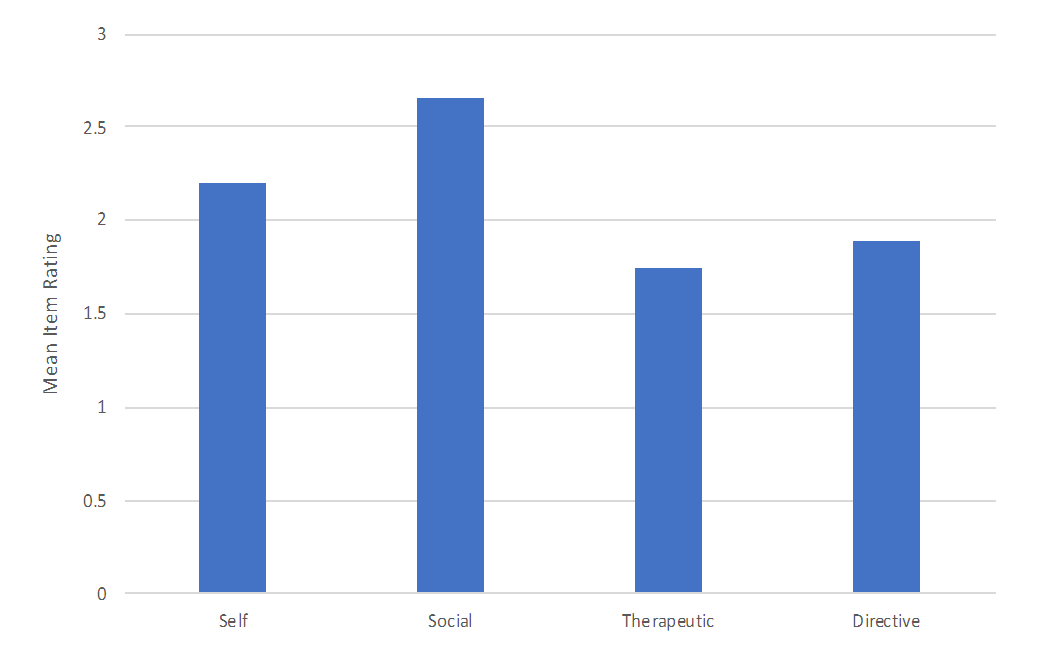

In addition, the mean item rating for each subscale was calculated (See Figure 2). The Social subscale had the highest mean rating, followed by the Self subscale and the Directive subscale, and the Therapeutic subscale had the lowest mean item rating. Paired comparisons showed that all differences were significant (p < 0.1) except the difference between the Directive and Therapeutic subscales (p = .08). It appears that people share memories online most primarily for social functions, followed by self and directive functions, and lastly for emotion regulation and coping. These findings are consistent with prior research showing that relationship maintenance and social connection is the most prominent purpose of memory sharing in everyday life (Alea & Bluck, 2003; Guan & Wang, 2020; Kulkofsky et al., 2010). | Figure 2. Mean item rating by subscales |

Taken together, the polit data suggest that the Purposes of Online Memory Sharing Scale (POMSS) is a reliable measure of the reasons for which people share their experiences online. In spite of being a brief, 20-item scale, it has excellent internal consistency. Three of the subscales - Self, Social, and Therapeutic – showed acceptable to excellent internal consistency reliability in the current sample, while the Directive subscale had poor internal consistency and should be used with caution. The positive association between the various purposes of online memory sharing and the frequency of memory-sharing activities provides support for the validity of the scale. Additional research is needed to test the reliability and validity of the Purposes of Online Memory Sharing Scale (POMSS) and to examine memory sharing in the digital age.

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a Hatch Grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. I thank members of the Culture & Social Cognition laboratory at Cornell University for their assistance.

Appendix A

Purposes of Online Memory Sharing ScaleWhy do you post about your experiences online? Indicate how much each of the statements below describes your reasons for sharing your experiences online.

References

| [1] | Alea, N., & Bluck, S. (2003). Why are you telling me that? A conceptual model of the social function of autobiographical memory. Memory, 11, 165–178. |

| [2] | Alea, N., & Wang, Q. (2015). Going global: The functions of autobiographical memory in cultural context [Special issue]. Memory, 23(1). |

| [3] | Baker, J. R., & Moore, S. M. (2011). Creation and Validation of the Personal Blogging Style Scale. CyberPsychology, Behavior & Social Networking, 14(6), 379-385. |

| [4] | Bluck, S. (2003). Autobiographical memory: Exploring its functions in everyday life. Memory, 11(2), 113-123. |

| [5] | Guan, L., & Wang, Q. (2020). Does sharing memories make us feel closer? The roles of memory type and culture. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/7udy4. |

| [6] | Hollenbaugh, E. E. (2011). Motives for maintaining personal journal blogs. CyberPsychology, Behavior & Social Networking, 14(1/2), 13-20. |

| [7] | Kulkofsky, S., Wang, Q., & Hou, Y. (2010). Why I remember that: The influence of contextual factors on beliefs about everyday memory. Memory & Cognition, 38, 461-473. |

| [8] | Lee, D-H, Im, S., & Taylor, C. R. (2008). Voluntary self-disclosure of information on the internet: A multimethod study of the motivations and consequences of disclosing information on blogs. Psychology & Marketing, 25, 7, 692-710. |

| [9] | Lenhart, A., & Fox, S. (2006). Bloggers: A portrait of the Internet’s new storytellers. Pew Internet & American Life. Retrieved October 13, 2011 from http://ii059.cn/SVehXS. |

| [10] | Lenhart, A., Purcell, K., Smith, A., & Zichuhr, K. (2010). Social media & mobile Internet use among teens and young adults. Pew Internet & American Life. Retrieved December 8, 2011 from http://1il11.cn/yub0Yk. |

| [11] | Nardi, B.A., Schiano, D.J., & Gumbrecht, M. (2004). Why we blog. Communications of the ACM, 47, 41–6. |

| [12] | Pillemer, D. B. (1998). Momentous events, vivid memories. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. |

| [13] | Schmitt, K. L., Dayanim, S., & Matthias, S. (2008). Personal homepage construction as an expression of social development. Developmental Psychology, 44(2), 496-506. |

| [14] | Stone, C. B., & Wang, Q. (2019). From conversations to digital communication: The mnemonic consequences of consuming and sharing information via social media. Topics in Cognitive Science, 11(4), 774-793. doi: 10.1111/tops.12369. |

| [15] | Wang, Q. (2013). The autobiographical self in time and culture. Oxford University Press. |

| [16] | Wang, Q., Koh, J. B. K., Song, Q., & Hou, Y. (2015). Knowledge of memory functions in European and Asian American adults and children: The relation to autobiographical memory. Special issue: Going Global: The Functions of Autobiographical Memory in Cultural Context. Memory, 23, 1, 25-38. doi:10.1080/09658211.2014.930495. |

| [17] | Wang, Q., Lee, D., & Hou, Y. (2017). Externalizing the autobiographical self: Sharing personal memories online facilitated memory retention. Memory, 25, 6, 772-776. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2016.1221115. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML