-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2020; 10(1): 8-15

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20201001.02

Children and Coping During COVID-19: A Scoping Review of Bio-Psycho-Social Factors

Mohamed Buheji1, Ashwaq Hassani2, Ahmed Ebrahim2, Katiane da Costa Cunha3, Haitham Jahrami2, Mohamed Baloshi4, Suad Hubail2

1International Inspiration Economy Project, Bahrain

2Ministry of Health, Bahrain

3University of the State of Para, Brazil

4I Coach Training Academy

Correspondence to: Mohamed Buheji, International Inspiration Economy Project, Bahrain.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The children’s mental, emotional, and physical wellbeing must be an utmost priority to be endorsed during the times of public health emergency that accompany fierce pandemic challenges, similar to COVID-19. This paper sheds light on the risks that children might face during lockdowns and emphasis on how parents should be a role-model for their children to cope during the time of uncertainties. Based on the synthesis of the literature, a balanced children's physical and mental wellbeing framework is proposed to foster a holistic approach towards mitigating risks and optimizing positive change, supported by parents facilitation. The authors recommend further testing of the proposed framework so that it can be generalised, while taking care of the limitations surrounded its development.

Keywords: COVID-19, Children Wellbeing, Mental-Emotional Wellbeing, Physical Wellbeing, Lockdown, Quarantine, Public Health Emergency, Pandemics, Parent Role during COVID-19

Cite this paper: Mohamed Buheji, Ashwaq Hassani, Ahmed Ebrahim, Katiane da Costa Cunha, Haitham Jahrami, Mohamed Baloshi, Suad Hubail, Children and Coping During COVID-19: A Scoping Review of Bio-Psycho-Social Factors, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 10 No. 1, 2020, pp. 8-15. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20201001.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The emergence of a new strain in the coronavirus family, officially named 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19 has induced a public health emergency of international concern, as per the declaration of World Health Organization (WHO, 2020a). The pandemic outbreak of the COVID-19 with the beginnings of 2020 started to poses a serious threat to global health due to the high fatality rate, besides its wide-scale ramifications on socio-economic and psycho-emotional aspects of people’s life. Arshad et al. (2020).According to the WHO figures during the mid of April 2020, more than two million cases have been confirmed worldwide, with more than 100 thousand deaths due to that outbreak. In many countries, drastic changes and stressful conditions have been developed over the progression of the COVID-19 disease, like imposing lockdown, school closures, quarantine, travel restrictions, social distancing, and fast-deteriorating business environment, Orgilés et al. (2020). This has also been associated with amplified media circulation about the outbreak, transformation in working and education patterns, and alteration in general lifestyle for the millions of people worldwide. The increase of symptoms or complaints of fear, anxiety, and uncertainty among the different populations in different countries raise the concern about how this may be associated with distressing health systems and nature of COVID-19 illness, Taha et al. (2013). This imposes the necessity for long-term planning and continuous holistic monitoring for public health and at a different category of society. One of these categories is the health of children. Buheji et al. (2020).Children and their parents since they are more disconnected from their direct support systems, i.e. extended family, child care, schools, religious groups, and other community organizations could experience many risks and hidden challenges. Samhsa (2020), Jacobson (2020).In this scoping review, the children's mental, emotional, physical wellbeing during the COVID-19 shall be explored. The paper shed light on parents, as a role model of their children and the front-line defense of the family against the risks of this pandemic disease. APA (2020).The challenges for children during the lockdown and its impact on their both mental and physical health are reviewed. Then how these risks could be mitigated to maintain the minimum wellbeing during lockdown is discussed. The role of the parents as role-models in front of their children during the pandemic as COVID-19 is reviewed to see the possibilities for embedding new behaviors. The paper calls then for the importance of family-children balanced wellness program, and conclude with a framework that helps to mitigate the risks and optimize the benefits of the children’s wellbeing during pandemics. Dessen et al. (2020).

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Challenges for Children During Lockdown

- Guaranteeing or being inside the house has become a real family challenge. This is because, although it is understood as the child's first interactional context, it should not be the only one. The way the child is kept in a restricted environment can cause damage to the care and bonds necessary for the quality of healthy growth and child development in the physical and affective-social aspects, compared to the quality of the socioeconomic and psychosocial relationships that the family has. After all, studies as (Brazendale et al., 2017) show that when children are on vacation or even on weekends, they are less physically active. Children from low-income families can be further harmed by nutritional deficits during school leaving. In the USA, summer feeding programs work for low-income children and have been encouraged to ensure that their needs are met. It can result in food insecurity resulting from loss access to school meals, Dunn et al. (2020). Under the supplemental nutrition assistance program children in certain developing countries would typically receive free or reduced-price meals. This program is essential as it addresses the children's nutritional needs, particularly among ethnic minorities and overweight children. Dessen et al. (2020).The pandemic (COVID-19) appears to have a significant impact on physical activity behaviors worldwide, Chen et al. (2020). In an attempt to minimize it, several countries have implemented restrictive measures of isolation and social separation. However, studies of Hammami et al. (2020) already suggest the negative consequences of such measures for the general population, especially children. A study in South Korea, in which 97 parents of young children were surveyed between March 27 and 31, 2020; 79 (81%) reported that their children’s screen time increased and 46 (94%) of 49 reported that their children’s use of play and sports facilities had decreased. (Lancet, 2020).The abrupt change in children's routine of being in confinement with the family at all times exposes other problems such as the lack of structure in the domestic environment to perform the necessary physical activities, for example (Liu, 2020). In this sense, ensuring the quality of life of your children during quarantine has become challenging for parents or guardians.Child abuse and neglect are one aspect of this pandemic. Parent stress is a major predictor for children's abuse and aggressiveness, CDC (2020), Buheji et al. (2020). Child protection agencies might have difficulties reaching out to these children during the lockdown, which might exacerbate the condition and school teachers might not witness the sign of abuse to report for higher authorities. Samhsa (2020).It is also noted that home confinement during the covid19 pandemic increases the risk of vitamin D deficiency and myopia. The literature defends that the family is the child's first interactional environment; it is where he develops the first social interactions, having a fundamental role in the individual's biopsychological formation. However, providing a change in the social environment is fundamental for the establishment of secure social relationships (Dessen and Poland, 2017).Another main challenge during children's lockdown is shifting to more toward screen time and digital technology. Being connected is positive and encourage them to live their life, but some children might experience cyberbullying, stereotypes, or age-inappropriate material and advertisement that promote unhealthy food, UNICEF (2020).

2.2. Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on Children’s Health

2.2.1. Introduction to Children Health Risks During Pandemics

- “While children are not the face of this pandemic, its broader impacts on children risk being catastrophic and amongst the most lasting consequences for societies as a whole” (United Nations, 2020, p.4).The impacts of COVID-19 present a variety of risks to the rights and safety and development of the children. The mitigation of these risks demands information, action, social responsibility, and solidarity. To act decisively, understanding at least the level of impacts at the mental and physical health should be on the front of our priorities. Although, the direct impact of COVID-19 infection on children may not be the major concern as per the preliminary data from observed cases in China and the US indicating that hospitalization rates for symptomatic children are between 10 and 20 times lower than for the middle-aged, and 25 and 100 times lower than for the elderly. In parallel, children could struggle more with psycho-social influences and alterations of the normal living environment. Jiao et al. (2020); Liu et al. (2020).

2.2.2. Children Mental Health During the Pandemic

- Children are one of the most vulnerable groups to the indirect risks of the COVID-19 epidemic. They may experience fears, uncertainties, and physical and social isolation and may miss school for a prolonged period. A preliminary study conducted in Shaanxi Province in China during the mid of February 2020, indicated that the most common psychological and behavioral problems among 320 children and adolescents (168 girls and 142 boys) aged 3-18 were clinginess, distraction, irritability, and fear of asking questions about the epidemic. Besides that, the mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19 represent an intense challenge due to the separation matter or damage to normal companionship. Brooks et al. (2020), Jiao et al. (2020). Quarantined children may get an increased risk of psychiatric disorders, post-traumatic stress disorders, and a higher risk of developing mood disorders, psychosis, and even suicide attempts Liu et al. (2020). Along, Children of frontline workers have also had to cope with alternative childcare settings or arrangements, and that parents need to be sufficiently guided, supported, and reassured. Sprang and Silman (2013).Brooks, et al. (2020) seen that children are at risk of mental and physical wellbeing due to being distant from the school environment, besides the turbulence of life routine. These found to be real stressors for most of the child population. Doubts about the disease itself, associated with the lack of personal contact with people in the domestic environment and a climate of family animosity, increase stress in the child population (Sprang and Silman, 2013).Orgilés et al. (2020) examined for the first time, the emotional impact of quarantine on children and adolescents in Italy and Spain, which are most affected by COVID-19. Parents of Italian and Spanish children aged 3 to 18 completed a survey with information on how parents perceived changes in their children's emotions and behaviors during the quarantine. The results show that the most frequent symptoms were difficulty concentrating (76.6%), boredom (52%), irritability (39%), restlessness (38.8%), nervousness (38%), feeling of loneliness (31.3%), restlessness (30.4%), and concerns (30.1%), and Spanish parents reported more symptoms than Italians, Orgilés et al. (2020).Teenagers may feel isolated from their friends and face major disappointments as graduations, seasons, and sporting events and other planned events are canceled or postponed. They may also experience frequent irritability, changes in weight or sleeping habits, repeated thoughts about an unpleasant event, and conflicts with friends and family, HC (2020).A significant impact is family violence against children, as a consequence of the great economic devastation of COVID-19, which generated widespread uncertainty and panic, leading to results potentially adverse to physical and mental health, including an increased risk of chronic diseases, substances abuse, depression, risky sexual behaviors, and post-traumatic stress disorder. CDC (2020), Sprang and Silman (2013), Taha et al. (2013). The indirect effect of the COVID-19 pandemic may lead to increased mental health problems among children and adolescents as a result of the public disaster, economic downturns, and social isolation. Economic recession affects adult unemployment, adult mental health, and subsequently, children may be maltreated. So, it is important to address mental health problems in children early to avoid negative health and social outcomes. Danese et al. (2020), Golberstein et al. (2020).

2.2.3. Children’s Physical Health During Lockdown

- Prolonged school closure and home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak could have spillover effects on the overall health of the children. Further, when there is a disturbing environment for the children, particularly at youth age, to grow with independence and to establish connections with peers over parents could pose a significant impact on their wellbeing. During epidemics, many children will suffer from a lack of normal experience in learning, socializing, and physical activity, Lancet (2020), APA (2020). The worsening of inactivity complications and time disturbances are much likely when children are confined to their homes without outdoor activities and interaction. Hence, this disturbance leads to irregular sleep patterns, and less favorable diets, resulting in increasing the child weight, Wang et al. (2020). With the continuing coronavirus spur, encouraging children to practice safe, simple, and easily implementable exercises is imperative to maintain fitness levels and reduce psychological distresses, Chen et al. (2020a). Further, in the wake of COVID-19, physical activity and health guidelines need to be considered through precedent actions, and precautions as students will return to normal life and resume their daily sports and physical activities, Chen et al. (2020b). In certain countries especially in developing countries or poverty communities, it may be more difficult to get nutritious food at home because of lockdowns or economic shock facing households, and there may be increased demands on parents and caregivers, hence that consequences for mal-nutrient could be potentially graved, WHO (2020). According to the World Food Programme, it is estimated that 369 million of children are missing out on meals school globally. Dunn et al. (2020), W0rld Food Program (2020). A question of significant importance within this devastating context would naturally raise: what is the most efficient and effective parental style to ensure that the psychological, behavioral, and emotional wellbeing and overall health of children are being well-protected and nurtured?

2.2.4. Ensuring Children Normal Sleep Pattern During Lockdown

- Both adults' and children's sleep pattern can change in the face of social isolation situation, Hammami et al. (2020); HC (2020). The lack of a daily routine directly affects the child's biological clock, causing daytime sleepiness and difficulties to fall asleep at night, impairing the ideal growth and child development, since growth hormones are produced throughout the night (Hall and Guyton, 2017). Global movement behavior guidelines recommend children (aged 3–4 years) have 10–13 h good-quality sleep per day. For school-age children and adolescents (5–17 years), have 9–11 h good-quality sleep each day. Interviews with 15 parents of preschool children in Beijing, China, found, nearly all children were going to bed later and waking up later after the coronavirus pandemic. Moreover, children who are less active and engaged in more screen time are likely to have a night of poor sleep, Chen et al. (2020).

2.3. Mitigation of Risks on Children Wellbeing During Lockdown

- In an attempt to minimize the deleterious effects of social distance on the physical well-being of minors, health professionals have developed guidelines for activities that can be performed at home depending on the reality of each family (WHO, 2020). Physical distancing can be challenging for families. During a stressful experience like physical distancing, it is natural to have more fights among teenage and younger siblings and families (RCN, 2020).Some studies carried out to assess the physical activity of children on vacation or weekends have shown that they tend to spend more time exposed to electronic devices (cell phones, computers, video games, etc.), giving little time to sports or exercise, Brazendale et al., (2017). Therefore, WHO recommends 60 min/day of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity for 6–17-yr-olds, as well as muscle and bone strengthening. Hammami et al. (2020) practical exercise modalities might include aerobic exercise training on a bike or rowing machine, bodyweight training, dance-based aerobic exercise, and active video gaming. Hammami et al. (2020) seen these exercises will counteract the side effects of a sedentary lifestyle during this pandemic and thus will improve the immune system and fight diseases.UNICEF (2020) considered children and young people contracting COVID-19 are among the severely impacted victims and unless specific programs are set to address the pandemic’s impacts on children, the echoes of COVID-19 will permanently damage our shared future.Parents and carers should incorporate physical activity into children’s daily routine and period of sitting should be broken by stretching, educators should incorporate healthy movement into the online lessons, health professionals should reinforce their positive association with children’s health through telemedicine, Governments should engage influential people in the promotion of such messages, and the media should provide regular messages to promote physical activity. Brouwer et al. (2018), (Lancet, 2020).

2.4. Parenting During Lockdown

2.4.1. Role of Parents Towards Children Wellbeing

- A parent always required to shape a clear understanding of their roles to protect and foster the holistic health of their children. However, the main challenge for modern families has become more focused on caring to educate their children. The characteristics of today's society, such as globalization, economic instability, insertion of women in the labor market, redefinition of roles, long working hours, divorce, single parenting, recombined families, media, among others, establish challenges peculiar to families, especially during public health emergencies, as the case of COVID-19. These demands become more complex in the face of such a pandemic situation (Chen et al., 2020a).Parents should keep their children safe by open trusted communication, using antivirus and checking the privacy settings to minimize data collection, encourage them to use video games that require physical movement and healthy habits, and balance between online and offline activities. Dalton et al. (2020).Parents should be aware of how this pandemic can affect children's physical and psychological well-being. Unicef (2020) recommends open dialogue to resolve any doubts about the coronavirus by children. Among the main measures, Unicef encourages asking questions and listening very carefully to evaluate how to help them cope with the current pandemic. Parents might invite the children to talk about what they know or understands about the subject, discovering what and how much they need to intervene or explain, or to develop strategies using maybe games, drawings, and stories to build proper acceptance and appreciation of the new situation or start a conversation. Unicef sees that in the case of very young children, reinforcing hygiene practices without stimulating new fears is sufficient.Valuing what the child is feeling and showing himself available to talk is fundamental for him to feel supported and protected, Unicef (2020). Resorting to honesty and providing explanations in a way that she understands is crucial to the success of communication, always prioritizing the truth instead of lies by consulting reliable sites, Jacobson (2020). For example, children should be explained how they could protect themselves and others by encouraging hand washing, or by covering their nose and mouth with their elbow flexed when sneezing or coughing. The parents should show the collective community activities that are putting such necessary measures to ensure safety and return to daily activities. Dalton et al. (2020).

2.4.2. Parents as a Role-Model During Pandemic

- Parents had to go through two challenges during the COVID-19, providing care for themselves and their families while playing the role of mentoring their children to make them better prepared for long term pandemic. CDC (2020), Jacobson (2020).Parents' stress or anxiety found to be influenced by their children behavior. For example, outgrown behavior as bedwetting, excessive worrying or sadness, unhealthy eating or sleeping habits, difficulty in attention or concentration, and unexplained headaches or body pain. CDC (2020), WHO (2020c).The challenges for the parents during a pandemic crisis like COVID-19 is that they need to explain to their children about the outbreak and explain or share facts in a way they can understand it, but also it does not alarm them. The dilemma is how to assure children in times of uncertainty and become role models for them in reacting to a dynamic event, Taha et al. (2013).Uchida et al. (2014) described the effect of school closure due to the 2009 influenza (H1N1) pandemic on parental and children behavior. The Japanese study emphasized that parents can play a role in engaging their children in out-of-home activities as part of the control measure.Parents are used to having their children in a controlled environment. COVID-19 pandemic is outside of their control. The parents are worried not just of the possibility of getting infected by the virus, but about the other socio-economic impact or issues related to their livelihood that this pandemic might bring along. Wang et al. (2020).Parents should manage children's anxiety if they are constantly exposed to epidemic-related news. Wang et al. (2020) advised building direct conversations with children to alleviate their anxiety about COVID-19 related issues.Wang et al. (2020) seen that parents are often important role models in healthy behavior for children during the COVID-19 pandemic, besides monitoring child performance and behavior, parents also need to respect their identity and develop with them self-discipline skills. WHO (2020c) emphasized the ofimportant role of the parents in following community-based strategies to eliminating the threats of COVID-19 and help their children to cope with the stress of the pandemic consequences? Arshad et al. (2020).A parent is expected to deal with abnormal situation with normal reactions. Part of the community-based strategies recommended by WHO and collaboration with UNICEF is to try to keep the children in regular routines and schedules, as much as possible. Also, parents can work on providing age-appropriate facts about what has happened, explain what is going on, and give them clear examples of what they can do to help protect themselves and others from infection.

2.4.3. Times of Lockdown Embedding New Behaviours During

- Children should be taught more good health behaviors during times of lockdown. For example, it is time to show children and reprogram their old paradigm about the importance of healthy food, selective eating, regular exercise, to be away from the phone or other influencers, etc. (Tavor et al., 2017).Children at risk, overweight/obese, not doing any physical activity, non-healthy eaters, not having regular sleep periods, should surely be the priority of parents during the lockdown. Brouwer et al. (2018).

3. Synthesis of the Literature

3.1. Importance of Family-Children Balanced Wellness Program

- Based on the synthesis of the literature, children need a well-balanced wellness program during lockdown that has several drivers that would ensure the children would maintain suitable mental-, emotional- and physical wellbeing. At times of lockdown and emergency environment where uncertainty would be high, it is very important for the family members, specifically parents and carers, to compensate with tools that would eliminate the feelings of threats to personal or loved one’s health and safety. Jiao et al. (2020).Therefore, WHO and other leading international, regional and even national public health entities need to promote more effective family lifestyle framework during the crisis, specifically here pandemics as COVID-19, which could effectively help to promote change in behavior, rather depending on policies and guidelines, WHO (2020a, 2020b, 2020c). The benefit of such a framework is expected to reflect on even management and mitigation of stress. Vafaeenia (2014) confirmed that establishing wellness programs assists people in adopting positive behaviors leading to healthier lifestyles in all aspects such as social, mental, emotional, spiritual, and above all physical wellness thus ending in developing positive behaviors. Brazendale et al. (2017).

3.2. Other Influencers on Family-Children Balanced Wellbeing Program

- There are two types of family-children balanced welling environment: physical and behavioral. The physical environment requires elements that relate to the children’s ability to physically connect with their environment. This encompasses the home layout, the bedroom comfort, the play or study area, the temperature, the air quality, the lights, and the noise affect. Baloshi (2018).The behavioural environment relates to how well the children connect with others, i.e. be it family members or other children, and it carries both within interaction and distraction. Physical environments can significantly impact children participate in physical activities, either positively or negatively. Their participation will differentiate if the family has secured area, as for the playground activity area, bicycle paths, or any other safe physical activity.

4. Review Methodology

- The multinational team worked on assessing the mitigating the challenges in children's mental, emotional, and physical well-being during a pandemic were assessed independently. The literature was collected from Portuguese, or Spanish were translated to English published references. This paper established the following research question: ‘what are the challenges for children's mental, emotional, and physical well-being due to COVID-19?’. Based on the synthesis of the literature review, a comprehensive framework is proposed.

5. Framework of Risks Mitigation for Children Wellbeing During Pandemics

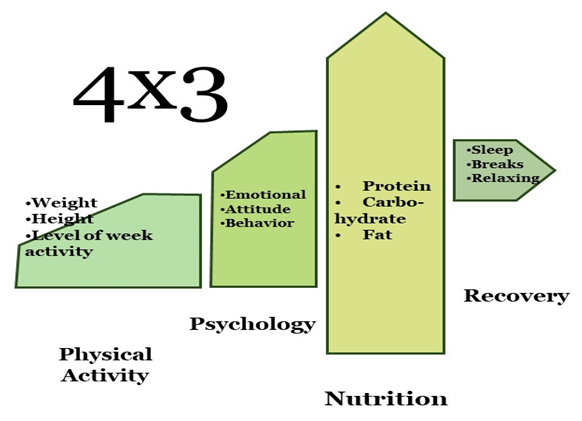

- For achieving and maintaining children, mental and physical wellbeing parents should establish a high level of physical activity, good mental health support, and ensure minimum uncertainty in the surrounding environment, besides good nutrition and lead to recovery, Danese et al. (2020). This cannot be achieved without a simple easily communicable framework that eases their implementation and gives them a gauge for measurement and thus, improvement. Dalton et al. (2020). Based on the review and the synthesis of different literature of many previous types of research that proposed holistic key engagement factors that affect the wellness and ease to set programs, for mitigation of risks and achievement of better wellbeing, the researchers propose the following framework in Figure (1). The framework in Figure (1) is made of 4x3 vectors, where the four main variables are made from the physical activity, the psychological status, the nutrition status, and then the recovery practices. Brooks et al. (2020).

| Figure (1). Children Physical and Mental Wellbeing Balanced Framework Proposed for Pandemics |

6. Discussion and Conclusions

- This paper provides insights regarding the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on children’s mental and physical health and the need for a concrete framework to help them overcome the difficult and uncertain times of the pandemic.During the COVID-19 outbreak and possible future epidemics, their needs to be a simple yet robust framework that helps the children and their parents to be resilient and overcome the challenges and instabilities that most probably would occur due to lockdown. Buheji (2020).The proposed children's physical and mental wellbeing-balanced framework proposed for the pandemics should ease the parent’s role and the demands for being also a role model for their family. The framework goes beyond the ordinary measures of protection or mitigation of risks on the child during times of emergency or uncertainty as experienced by the COVID-19. It is rather a framework that addresses, in a holistic approach, how the chances of the parents could be enhanced so that they can embed change in their children behaviors, be it a psychological and/or physical healthy lifestyle. The framework 12 variables, which are 3 in each of the four vectors, takes into consideration the need for parents-children communication models and measures that can be understood and gauged by all the family members. This 4x3 framework can be further developed and generalized through games, competitions, and even community programs. The more we manage to show success stories relevant to this or similar framework, the more the world would address the deep concerns of the unprecedented world turbulence on the child, and we would ensure they get through these difficult times with minimal risks and optimum gains. The WHO, the public health authorities worldwide and even the governments, have the right to, and in fact encourage to continue to develop plans, guidelines, and resources re-arrangement to encourage active, healthy, and socially empowered lifestyle for children and their family; however the researchers' emphasis that the simplicity of communicating the framework to different families and between children and their parents should be considered as part of the norm. WHO (2020a, 2020b, 2020c, 2020d).The limitations of this paper are that it could not specify the specific age of children where this framework could fit most. i.e. more work needs to be done whether this model would fit adolescent youth and children below six years. The research also does not encounter the level of parents or children's knowledge, means, feelings, motivation, etc. More research needs to be done in relevance to minor modification or alignment of the framework when causes for differentiation as gender, level of child fitness, and the family socioeconomic status are integrated. Further research is recommended in studying what exactly motivates a family to apply this simple framework in times of uncertainty, besides the simplicity of the model proposed.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML